#TAD s1e8

Text

The Artful Dodger, tumblrfied: "Untapped Potential"

9/?

#Second's TAD edit#The Artful Dodger#TAD s1e8#The Artful Dodger spoilers#Lady Belle Fox#Dr. Jack Dawkins#dodgerfox#Norbert Fagin#Captain Lucien Gaines#Frances 'Red' Scrubbs#Lady Jane Fox#Lady Fanny Fox

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

Altered Carbon s1e8 (spoilers)

Alright, so Rei provided an explanation that she had to use Bancroft to get Takeshi out of ice.

She’s kind of a yandere with a brother complex, speaking in anime terms (lol). She says she loves him, but it doesn’t stop her from hurting him by hurting people he cares about. She forces his obedience by threatening his new friends.

And she’s also the owner of the torture business. She’s the woman that put a criminal in a snake. She’s ghostwalker’s boss. She’s basically everything that’s wrong in this world and everything Takeshi despises.

Tense moment when he put a sword to her throat. But he can’t kill her, not really. That realization how pointless it would be and disgust when he throws away the sword is what makes the scene.

The elevator talk with ghostwalker was just classic Kovacs lol. On the other hand, I’m just a tad disappointed that this god ghostwalker was going on about was Rei. Just because she lives long doesn’t make her a god.

Takeshi put on a good performance when he “broke up” with Ortega, but at the same time it was just so obvious he hated doing this to her. I’m glad she figured out something was wrong.

Ortega getting fired for investigating too deeply is such a classic trope.

Lol, so Takeshi got Ava, Elliot’s wife out of ice, but she was put in a white guy’s body. Still, the Elliot family got reunited and she was accepted by her husband, so I guess it wasn’t so bad. However, this whole situation really makes you wonder about how much appearance means to people. Looks shouldn’t really matter to who we are, especially when people could change bodies, but still... people are supposed to have one body, it is a part of us just as much as a spirit. This system of sleeves messes with one part of what makes humans unique individuals.

Anyway, with Ava’s help, Takeshi concocts a lie to sell to Bancroft about his murder and frames Prescott, the lawyer woman with ambitions of becoming a Mat.

Interestingly, he still manages to figure out what really happened and that Bancroft was watching Mary Lou Henchy, dressed as his wife, falling to her death from some brothel establishment in the clouds on the day of his death.

I liked the idea with using the Rawling virus that killed Envoys in this plan to deceive Bancroft. Really clever.

Ortega finds Rei’s clones and fights them all. Idk, but this whole fight seems really stupid of Rei. If she was going to be so upset about losing all these clones then she shouldn’t have Ortega locked in there to begin with.

Sinister cliffhanger with Ortega getting completely hoodwinked by Rei in a little girl’s body.

0 notes

Text

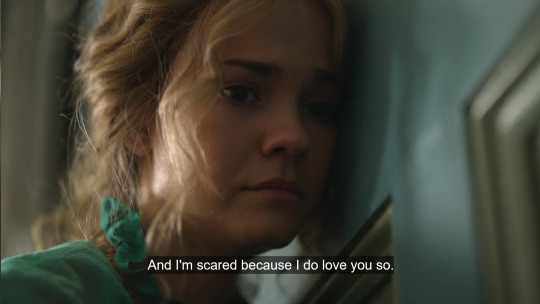

This is a love story 😭

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 7:

Belle: no sex before marriage

Jack: bummer, but fair

Episode 8:

Belle: I have an undiagnosed aortic aneurysm and my enlarged aorta could rupture at any moment, but carpe diem, guess I'm ready to cash in my V-card after all, but also, I very much could die while we're-

Jack, already taking off his pants: then perish

#p sure this is how it went#The Artful Dodger#TAD s1e8#The Artful Dodger spoilers#Lady Belle Fox#Dr. Jack Dawkins#dodgerfox

131 notes

·

View notes

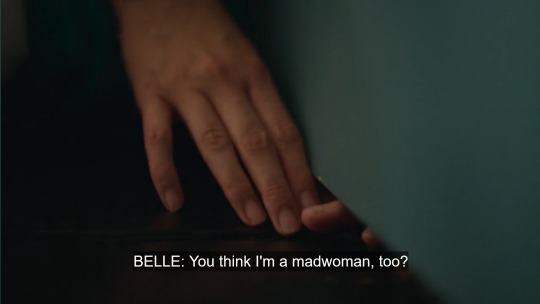

Text

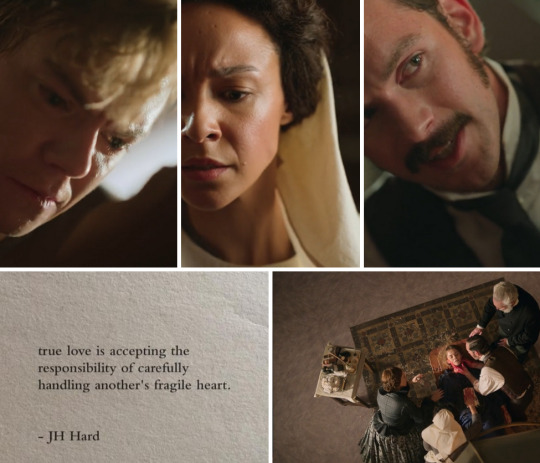

This too. This is a love story.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

I get that he fell asleep monitoring her pulse, BUT FORGIVE ME, THAT WAS NOT MY FIRST THOUGHT

31 notes

·

View notes

Note

Three!!

Thank you, Kaye!!!

Shuffle #3: “Bitter Taste” - Billy Idol

There's nothing I can do to change it now / But if I cut myself open, baby / You can read all my scars

And Spit at the Stars (And Scream in the Dark)

Rating: T

Word Count: 962

music shuffle fic game

Summary:

Belle dies on the table.

He puts his hands inside people for a living, for as little of a living as it is. When Jack strides down the street, the hard-packed dirt reminds him of the roof of a man’s mouth—the mouth of the very man he’s passing. He’s retrieved small objects (marbles, stones) from the noses of half the children who rush to tug off hanged men’s boots. He’s delivered them from their mothers, hand inside the birth canal as he eased slippery shoulders free. He knows what their fathers’ shattered elbows looked like before he doctored their wonky mending. He could identify a dozen men’s patellas by touch. Blindfolded.

Blood; blood always feels the same, but the veins that spill it, the flesh from which it seeps, are unique under his fingers. So he’ll remember this, and run back through it: Did he open cleanly? Did he disturb her vital workings when he reached all the way into her, to the back of her, positioning the noose and pulling the thread taut? Did he tie it too snugly? Before all of it, did he hold the mask to her face too long, drowning her in ether?

When he feels—

When he feels Belle’s heart stop—

It doesn’t even mean blood to him. Jack’s palm is on her non-rising chest, everything he never felt from the inside flashing through his mind behind his unfocused eyes. Bone, lungs, the chambers of her heart. He would occupy those chambers, live inside her, join her there. His red hands scrabble up her neck. Nothing in her throat jumps against his fingers.

Hetty takes him by the shoulders, and he twists, twists like the babies who wriggled their way into this horrible, hurting world with the help of Jack’s hands. But Hetty is determined and strong; she will brace herself beneath the arm of an amputee to raise him onto his remaining leg. She clutches Jack’s shoulders, and he jerks, eyes fixed on Belle’s face, no longer flushed with agony. Or life.

“She wasn’t in pain, Jack,” Hetty is saying. “You did that for her. She wasn’t in pain.”

Her voice is thick like the tears pushing their way out of his eyes to splash down his cheeks. He can hear Belle’s mother crying now, a lonely wail that calls Jack back to storms at sea, the wind and the slanting rain.

When he shakes out of Hetty’s hold, it’s because she lets him go, dropping her hands. He looks at her wildly, finally. A tremor touches each of her features in turn—her brow, her nostrils, her chin—but she stares back at him, hiding nothing. How do they take care of this? How can they possibly be the people in charge? Who will nurse them, hold a mask over their nose and mouth to shelter themfrom their pain? Of all the times in his life Jack’s needed someone to step in and save him—

Sneed is drawing a sheet over Belle’s body. Jack takes snatching hold of his arm, but Sneed turns his head and meets Jack’s eye with such sympathy. Chest heaving, Jack senses that he doesn’t so much look at Sneed as watch the man watch him; he feels like a picture on a wall. Rather than wrest Sneed away from her, Jack only squeezes and releases his grip.

“Enough!” Gaines rings out, tolling Jack’s hour like the bell in a clock tower.

His guillotine hand comes down on the back of Jack’s neck. Jack shrugs him off violently, and before Gaines can make another grab for him, Sneed steps between them. The sheet ripples down over Belle.

“He isn’t going anywhere,” Sneed grits out with a hard edge.

At first, Jack thinks Sneed is insisting on preventing his arrest altogether, but then Sneed adds, “Look at him,” and Jack understands Sneed isn’t taking a legal stand, just telling the predator in Gaines that his quarry is too weak to run.

“It will be you under arrest if you’re wrong,” Gaines assures Sneed, striking Sneed’s shirtfront with the barrel of his pistol.

At the casual hostility of this contact, Jack’s hand darts out, fingers flexed like a claw; he’s prepared to choke the life out of Gaines with his tie. Sneed’s reflexes are just as quick—something for which Jack rarely gives him credit—and he knocks Jack’s hand aside before he can assault the Captain. Hetty, too, is stirred to action, taking both doctors by the elbow and giving a backwards yank, away from the danger of Gaines’s gun and their own impulsive stupidity. For a moment, they are, the three of them, connected, and loss is the current running through them.

“Gentlemen, some self-control. For her parents.” This can only, and does, come from Hetty.

The next thing Jack knows, he’s taking hold of the brass railing and hauling himself up into the wooden stands. He mounts the stairs, fighting shock, catching the toe of his boots on the steps until his climb becomes a stagger, a flail, until his palms press the theatre’s back wall and he turns and slumps down it. His head lolls as he takes in the view. Why do the spectators come? Why the children to the gallows and the grown men to the surgery? Is the attraction that the person on the table has a fighting chance, or is there always a cruel presumption that life can’t win? Once the surgeon’s fingers have plumbed your insides, you’re doomed? The lesson from up here is: never let life crack you open.

Jack could strangle the fool who keeps asking if Belle’s breathing. He could kill them with his bare hands. He looks down at the shape in the sheet, the body he knew from the inside.

Fully.

#my writing#TAD song fic#The Artful Dodger#TAD s1e8#The Artful Dodger spoilers#dodgerfox#Dr. Jack Dawkins#Lady Belle Fox#Hetty Baggett#Dr. Rainsford Sneed#The Artful Dodger fic#dodgerfox fic

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fair Days

Fandom: The Artful Dodger

Pairing: Hetty/Jack

Rating: T

Word Count: 2092

Summary:

Jack's troubled by questions of love and fairness. Hetty knows something of both.

Jack says “fair” and it sounds to Hetty the way Prof’s Latin looks. She knows it has a meaning, and she’d have to look it up to understand Jack’s particular usage: “fair” as in “fair, how is any of this.” She can’t be angry with him. It’s actually a sort of miracle that he can still ask the question when she knows enough of where he comes from (a place where he was cold, a place where childhood wasn’t) and what he was there (desperately, cyclically poor).

She knows that he’s afraid, and that “fair” and “fear” are never far from one another. “Fair” is the colour of pages containing notes in a language neither of them can read, the colour of some people’s skin. “Fair” is the colour of linens that get thinner without getting much cleaner because you scrub them and scrub them but can’t afford proper soap. “Fair” is almost meaningless, certainly thin, and not really that attractive next to the gilded things that only seem fair, like spending however much time, performing however much research, opening up however many cadavers, to save the life of the golden-haired governor’s daughter while a dozen others lie in the wards, waiting to even be looked at, let alone looked after.

Hetty cares for Belle. Belle’s brought ideas into the hospital, where they’ve become real. Hetty can confidently say that, since Belle inserted herself, there has been less suffering and more lives saved. Belle herself ought to be saved. Maybe any other outcome would be unfair.

But Hetty doesn’t know every shade of fairness, just the one on the linens that got thinner without getting much cleaner. She remembers watching them flap on a line above her head as the meek sunshine poured through, her little sister’s head on her lap as she darned her knee-high socks the way Hetty showed her. She’d been wearing them when she’d tried joining the race the older boys were having and tripped, tearing a hole in the rough wool. Their brother stood on the other side of the gap between the tired houses, practicing pugilism against his shadow in the pale-yellow light Hetty could pretend looked as luxurious as cold butter if she squinted just the right amount.

“Like that?” her sister asked, swinging her arms up to present the sock below Hetty’s nose and then dropping them again before Hetty could really look.

Still, she said, “Exactly, my dear,” and smoothed a hand across her sister’s forehead.

“Going to tell me I shouldn’t have let her run?” their brother puffed, intimidating the clapboard with fists that miss it by inches.

“No,” Hetty promised, “only that you should’ve realized that’s what would happen when you took her along.”

“She should know better. Since that cough she had last winter—”

Hetty pillowed her sister’s head in her apron. The way it covered her ears might’ve been an accident.

“You are fourteen, she is four,” Hetty singsonged, parroting their mother. She was sick, you are well.

Hetty remembers, still, seated on Jack’s bed, the terrible coughing that battered the second-floor set of rooms her family lived in. How it was wild, like a trapped bird that was trying to escape and kept colliding with the walls. How her mother arranged for her to stay with the rich people whose children she minded (how “stay with” meant “do light work for,” changing white bottoms and laying silver rattles out straight on a tray). How she was brought home again when her sister’s suffering had eased enough that their mother and father felt the danger of Hetty catching it too had passed. How she would sit her sister up at night before the soft tickle could become a hacking that would wake their exhausted parents and slip in behind the beginning-to-wake three-year-old, letting her fall back to sleep propped up by Hetty’s own body, her hot back to the front of Hetty’s nightgown—linen worn thin.

Her brother’s still hands marked his contrition. No matter their ages, at eight, Hetty was the boss of them both, counted upon to stitch up her sister’s socks before the littler fingers knew how and, just a week previous, her brother’s cheek when a boy up the street had decided punching the air was an invitation to get punched back.

He started to move his feet instead, somewhere between the action of the sport he was so taken with since sneaking into a match a month ago and dancing. Their father had shown them that and Hetty hadn’t forgotten either, even though it had been a while since their father last danced.

“What do you think—”

Hetty shushed him.

From the second-floor window, their parents’ voices sang down. They were arguing. Her brother heard it too, which was why he didn’t protest being silenced.

“What’s ‘manumission’?” her sister wondered, but Hetty didn’t answer, and she went back to work on the sock.

Too rare. That’s what manumission was, according to their father. It was a word that didn’t come from any of their own histories. Hetty’s mother had been born free in England; her father had been born into enslavement in Haiti, seven years into the revolution, six years before its end. Both halves of Hetty’s parentage had their heritage in West Africa. Her father had named Hetty’s brother George (after the king who’d ascended to the English throne in the year of his birth) and Hetty’s sister Adelaide (after the next king’s queen) because, as he’d told them, those names were powerful. Her mother had given them their middle names—George Kayode, Henrietta Nkechi, Adelaide Bola—because, as she’d told them, those names were powerful too.

The argument, from what Hetty could hear, head resting back against the side of the house, eyes on the waving linens, was about her father’s impatience, her mother’s bid for safety. He was deeply involved in the abolitionist movement; that was one word they had all heard many times. There was always more that could be done, and now he wanted to do it abroad, to go to America where people were still enslaved.

“What about your children?” Hetty heard her mother demand.

“What about theirs?” her father shot back. “In America, the children of the enslaved continue to be born into the institution!”

“Your children, here, have the chance to have a family. A mother and father. If you leave them, how would that be”—and here it came, whooshing through the linens, the word forever dyed their colour— “fair?”

“My love…” Her father’s voice lowered, but she strained to hear. “…fairness for one family is not fairness.”

In Jack’s room, Hetty tells him that to love is to peel the skin off your heart. Her father, the child of revolution, did it when he sailed for Massachusetts. Born into upheaval, he was always restless. He went from Massachusetts to New York. Dangerously, to Maryland. Worse, to Georgia. He spoke at abolitionist events, printed pamphlets, taught people to read. He knew how because he’d learned alongside George—George, who adopted a solemn sense of responsibility when their father kept delaying his return, going north for work in order to send more money home. He wrote to them, and they could see that it peeled the skin off his heart to be away from their warmth. Hetty stayed with their mother and sister, becoming a nurse. An opportunity arose to do good in Australia, and to do it with perhaps more dignity than she was afforded in England. Hetty felt the blade’s edge inside her chest as she left her home and took her powerful names.

When her mother died, Hetty was surprised to be written to and told, not only this hard news, but that Adelaide was choosing to follow Hetty rather than George, after whom she’d always trailed as a child. Her sister, still a teenager, was coming to the colony under the protection of a friend of their mother’s. Except the journey by ship was so long. Except Adelaide’s body had been disadvantaged against illness so young.

“You’ve never really loved anyone, have you?” Hetty questioned Jack a moment ago.

It’s mixed up in her head, whether she held Adelaide again, whether she nudged her upright in the middle of the night to stop her from coughing and let her fall back to sleep propped up by her own body, Adelaide’s hot back to the front of Hetty’s nightgown—linen worn thin. Or if that was only once. If Adelaide arrived in the colony as a memory and a long box, one of sixteen the crew had made by the time the illness receded from their vessel. Did Hetty ever say Adelaide’s name with joy on this soil, or only scream it in pain? When Adelaide was a child, they’d called her Lady.

“It always hurts,” Hetty tells Jack. “No matter what you do.”

He thanks her for the notes she can’t read and leaves.

She should go; they’ll be needing her downstairs. But it’s a miracle that Jack can still expect life to be fair, another miracle that there’s still somebody Hetty wants to love when love is such a merciless, heart-peeling thing.

Because it’s good too, love. There’s so much more good than pain in it. It’s George unashamed to dance in front of his friends, saying, “We do this at home,” meaning three streets away, where their father taught him the motions, saying, “We did this at home,” meaning Haiti, where his mother taught him the rhythm because she couldn’t teach him to read, saying, “We did this at home,” meaning back across the ocean. It’s Adelaide watching Hetty sew until Hetty teaches her how, boxing George’s unsuspecting shadow when George sits down to eat the dinner their mother, in another show of love, made for them. Love is her father’s letters from Boston and George’s letters from Manchester. Though the peeling hurts, it's astonishing just how much heart there is to peel.

Hetty’s been at this hospital longer than Jack has, and she remembers when he was new. He used to put instruments into his pockets, used to the tilt of a ship making things slide away. She told him it wasn’t smart, wasn’t clean, and he stared at her because clean hadn’t been a priority when water was pouring in and men were bleeding out. Eventually, impulsively, Hetty snatched a pair of forceps back out of his pocket during a surgery. He instinctively grabbed her wrist; she instinctively cuffed him on the ear—call it the latent training of having a brother always practicing his boxing in front of her. She’d been stanching the patient’s wound and the contact left blood in Jack’s hair. Some of their audience in the theatre that day erupted in fury at the insolence, others roared with laughter. Hetty was sure she would, at minimum, lose her position at the hospital, but Jack just let her go without a word and continued with the procedure. Afterwards, he shook her hand.

Is that when it happened? Was it when some bastard tried to grope her in the street and Jack accidentally sent him tumbling down a flight of stairs into the below-street-level door of the mercantile? Was it when Jack told her quietly that reading doesn’t come easily for him, trusting her to help him, never assuming, as others had, that she wouldn’t know how? Was it when the small child who’d coughed through the night was deathly still in the morning? Was it then? When Hetty gulped down the first cry and fled the ward at a run? When Jack found her heaving with the sobs that would not expel her sadness? When he didn’t know what to do, but he stayed? Or the day a patient died on the table and Jack left the theatre looking calm, but at the wash basin he was trembling with rage, so Hetty took his face in her hands, and his came up to hold her the same way, but they were dripping wet, so the water ran down the sides of her face, and she remembered the day with the blood in his hair, so she said something, but then they were kissing, and she was the one trembling. Was that when?

She’s been in love too long—all her life—and she does it really well, sitting here in Jack’s room by herself. She gazes out the window. The sky looked like rain earlier, but now, the day is quite fair.

#my writing#The Artful Dodger#The Artful Dodger spoilers#TAD s1e8#Hetty Baggett#Dr. Jack Dawkins#Hetty x Jack#The Artful Dodger fic

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fagin, istg, if you turn Jack in, you may not die, but you will BE DEAD TO MEEEEEE

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

If Fagin, Jack, and Oliver are the thieves, explain to me how Hetty and Fanny are stealing this entire episode????

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hetty just breaking my entire fucking heart in this scene:

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'M SO SORRY FOR HOW THIS LIVEBLOG IS ALREADY GOING, BUT THE TRANSITION FROM JACK AND BELLE ABOUT TO BANG TO THIS MAN GRIPPING A LEVER???

15 notes

·

View notes