#Tom Nancollas

Text

Seashaken Houses by Tom Nancollas: lighting the reefs of the sea

Tom Nancollas, Seashaken Houses: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet. London: Penguin. 2019. (2018.)

Blackwell’s affiliate link.

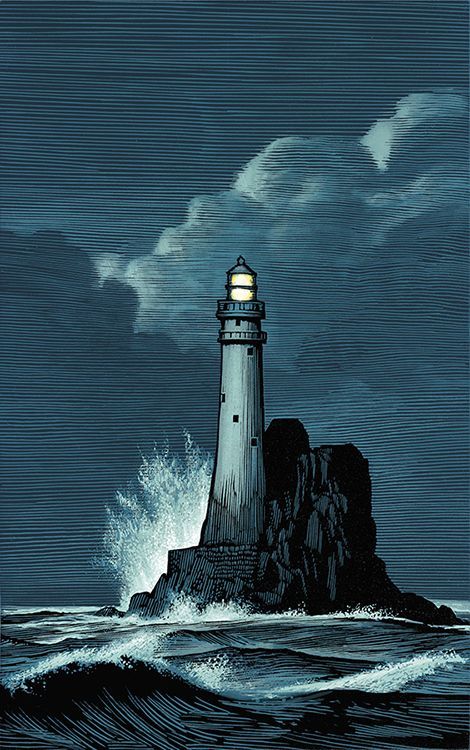

Covert art for Seashaken Houses: a drawing of Fastnet Rock lighthouse with a wave breaking halfway up the lighthouse’s sides. (Illustration by Chris Wormell.)

Seashaken Houses is part history, part meditation on the difficulties and ambitions inherent in…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Jacket for Sea Shaken Houses by Tom Nancollas

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Review of “Seashaken Houses”

As a teenager in the 90s, I was interested in lighthouses, and visited a couple (Hook Head and Mew Island) before they were automated. I think what I found appealing was the 19th Century technology, the neatness and definiteness of the constructions. Lighthouses are popular with the public for their ‘nautical gaiety’, although, as workplaces, they are solemn. If I had been in America, I might have studied NASA rockets instead. Irish lighthouses represented a relatively accessible, if anachronistic, form of high tech. So I think, when I read about them, that I was after a shot of technology, precision and good order, not gaiety. Looking back, I wonder now whether I was completely immune, though, to the main appeal of lighthouses, which is their civility. This quality is sometimes emphasized by wild surroundings, but it doesn’t have to be. The politeness and formality of a lighthouse stands out in any setting. In black and white photographs and section drawings, from old illustrated books, their solidity and precision appealed to something in my personality.

I’ve moved on from my lighthouse enthusiasm, but recently picked up Seashaken Houses: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet by Tom Nancollas. It’s an interesting book to me for a few reasons. Nancollas works in building conservation. He is a graduate in classical studies and a self-described antiquary: though in his mid 30s, he uses the letters FSA after his name. It will come as no surprise that he is a bit of a young fogey. The book is a selective history of the rock lighthouses of these islands from the perspective, primarily, of architectural history.

The first thing to note is that focusing on rock lighthouses is a bit like focusing on express locomotives or thoroughbred horses. These buildings form an elite category among lighthouses. Even more than the typical lighthouse, they are high-end engineering projects, on which money, attention, and craftsmanship was lavished. The first wave-washed towers were civil engineering marvels. As such, they are compatible with the values of the ancien régime: the marvellous rather than the uniform. Every rock lighthouse is a bespoke item, a custom job, consisting of thousands of precisely tailored stone blocks, dovetailed into the bedrock. These towers are notable for their symmetry and crystalline order.

After a couple of freakish and inadequate attempts which lasted only a few years, the design of rock lighthouses settled into a pattern. The archetype was the third Eddystone lighthouse, designed by John Smeaton. Constructed of granite blocks, it was a tapering circular tower with a lantern at the top. Smeaton’s tower established the compelling architectural image of a hollow, inhabited pinnacle of rock, almost completely unadorned. The development of a new building type is the most exciting event in architecture. It is to the representatives of this once new genre of tower that Nancollas devotes his book: Eddystone, Bell Rock, Haulbowline, Perch Rock, Wolf Rock, Eddystone (again), Bishop Rock, Fastnet.

As an antiquary, Nancollas comes to his subject with somewhat vague qualifications. He knows a bit about architectural history, though he is not an architect. He has a taste for authentic idioms, though he doesn’t pick up some of the most distinctive lighthouse terminology—wave-washed, for example. He is neither an engineer nor a seaman. People who like the book seem not to object to the gentlemanliness of his project. He is a personable narrator, and people seem inclined to entertain his pretensions to history writing, particularly the insinuation of his own experiences into the story. Though he can come across as a bit privileged, it would be a trap to conclude that due to having been well brought-up he must be an upper-class twit. He is temperamentally suited to recording what defines lighthouses from an architectural point of view: their civility, their good form.

So the book, even if it is, in truth, less a passion project than a vehicle for Nancollas’ writerly ambitions, is successful. He covers all the bases, as far as the architectural history of the buildings goes. I am not sure than he is so strong on placing the wave-washed towers into context. They exemplify the endlessly mysterious dictum “form follows function”. Nancollas doesn’t mention the slogan, and I don’t think he would perceive it as a mystery, so much as a glib banality.

The towers were machines and participants in a proliferating network of signalling and navigation. Cooped up inside, the keepers led dreary lives of unrelenting solitude, slaves to the machinery. What is missing in this world of duty and responsibility is a sense of exuberance or expansiveness. The engineering of any one of these towers may have been a virtuoso performance, but occupying them was not. Physically restricted to a small compass, the keepers could scarcely give free rein to any aspect of their personality, while, outside, the ungovernable sea did its own thing, day and night.

As a teenager I read, in a book about Scottish lighthouses, about a keeper who was studying mathematics in the evenings. This fact seemed resonant and stayed with me. In addition to possessing the circular symmetry of most lighthouses, the wave-washed towers reflect a complex, orderly process of assembly. The premeditated, scripted sequence of operations was a way to guarantee the unshakable soundness of the towers. This is a property which it shares with the 19th Century development of mathematical formalisms, intended to place mathematical proof on an unassailable foundation. But there is a more psychological relevance of mathematics to the life of a lighthouse keeper. Mathematics—reason’s dream—is a mental practice of domination, of control. The mathematician is always the wrangler, never the subdued, always the buttoner-up, never the buttonee. It is a form of agency which is available even in the most isolated and confined quarters, when one is “bounded in a nutshell”.

A preoccupation with fallibility infuses the whole operation of lighthouses. In the 1850s Michael Faraday remarked that “There is no human arrangement that requires more regularity and certainty of service than a lighthouse.” The seriousness of the task in hand justifies the omission of ornament. Foibles and fripperies are excluded. But from the architectural historian’s perspective, the 19th C towers still have some traces of politeness, some flourishes, some relics of old decency. Looking at them, it is easy to understand the spirit of Horatio Greenough’s statement—“In nakedness I behold the majesty of the essential instead of the trappings of pretension”. The order of the day is structural necessity, not ornamental contingency, forms that relate to the job of exhibiting a light high above the water rather than extemporized curlicues. In that sense, the towers obey the modernist logic of form following function. The philosophy of their design is an appeal to “fixed and unchangeable laws” and a dismissal of “eccentric opinions” (Laugier). It is an ambiguous perfection.

Nancollas doesn’t seem to appreciate the notion of modernism in this sense. He doesn’t use the term in a positive sense, except to remark, bizarrely, that an Irish Lights helicopter looks “reassuringly modern and functional”.

The structural integrity of the towers visited by the narrator is a prerequisite for the continuity of the service they provide. It is just one aspect of their reliability. In gentlemanly style, Nancollas suppresses the technicalities of the lights’ construction and operation. For example, he seems unaware that an ellipse has two unequal axes, and thus mangles a description of the geometrical definition of the shape of Wolf Rock’s tower. Lamenting the modernization of Bell Rock, he claims “it requires only a little ingenuity to let the old coexist with the new, even offshore.“ There is a risk, in avoiding technicalities, that the achievement becomes indistinct and dull, the account facile.

In the early days of mass production, the perfect precision of a machine’s construction was understood to mean perpetual reliability. We are less inclined to make this connection now—the possibility of human error in manufacturing has receded as a cause of failures, replaced by more exotic problems due to complexity and economic constraints. Little expense was spared in the construction of the rock lighthouses, and their designers were cautious and conservative in their technical specifications. It’s clear that this quality is part of their particular appeal. Studies suggest that the towers have a good chance of surviving future rough seas, even with climate change. They have become monuments.

Less appealing is the human story of their inhabitants. Nancollas remarks of the Bell Rock lighthouse: “The tower is painted a pure white, blotched in places by liquids cast from the windows (probably coffee and urine, from the time when it was inhabited), smoke damage (from a fire in the 1980s), and a big streak of green-black wave-spatter on one side.” A dour, dangerous life. Automation was a relief. Let these obdurate things enjoy the solitary life that suits them.

Nancollas has a bit more personality than the topic of his book suggests. Alcohol and nicotine are part of his stories; there is a slight loucheness that goes along with the fogeyishness, for better or worse. When smells are mentioned they tend to be repellent rather than sweet. He is more-or-less oblivious to politics; where he could espouse a firm position on the Troubles he prefers to tell a conciliatory story. Despite visiting two Irish lighthouses, he apparently manages to miss the fact that Irish Lights is a cross-border body. Rather than sticking to the facts, his writing involves a certain amount of self-indulgence. His style is unbuttoned and a little verbose, sometimes drifting into grandiloquence—but then, I’m not his target audience. The style does, however, seem unsuited to the plain subject matter. It leaves me expecting to see something more decorative, perhaps more feminine. That is what his language promises. The radical uncosiness and stern splendour of the lighthouses evokes the emotionally toxic, a characteristic not to be dwelled on.

The chief fault of Nancollas' book, though, is his airy indifference to science and technology. This is all too predictable, coming as it does from a classicist and a conservationist. The spirit of modernity, of systems and methodical processes, seems to have passed him by, along with the World Wars. He is enviably untroubled by the imperatives of keeping technology running. When he alludes to such processes, it is in dismissive terms: the daily routine of preparing the light is like "solving a Rubik's cube"; the technician's job of disassembling and reassembling a generator is a “puzzle". Nancollas doesn’t articulate the modernist metanarrative—the idea that a single correct solution can be derived quasi-mathematically from the statement of the problem, and that if the designer gets it right it will last forever. He doesn’t place the complex and demanding process of the masonry construction of the towers in the context of development toward digital technology, of carefully designed units assembled into reliable machinery. A basic premise of studying the classics is that human nature doesn’t change—that there is nothing new under the sun. But society and culture do change and new technologies bring radically new experiences. The rock lighthouses are of their time, redundant now. Nancollas doesn’t address the question of how to value this old hardware in the context of our new software. For him, it is yet another “puzzle”. New illumination technologies have made the flashing lights of navigational aids more abrupt, less gradual, an example of the kind of creeping qualitative change and dilution of historic character that makes conservationists despair.

0 notes

Text

Hope struck the Bar and sunk, followed by the stranding of the Friendship

- Seashaken Houses, Tom Nancollas

0 notes

Text

"...navigational gifts for the safety of all..." #lighthouses @PenguinUKBooks #TomNancollas #nonfictionNovember

“…navigational gifts for the safety of all…” #lighthouses @PenguinUKBooks #TomNancollas #nonfictionNovember

Seashaken Houses: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet by Tom Nancollas

When I was ambling around Waterstones a few weeks back, as you do, my eye lit upon the rather lovely cover of this book; and since the subject matter was something in which I have an interest, I was very tempted… I resisted for a couple of weeks, but as I mentioned in a previous post, I finally succumbed. Why, you…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

Hello! Number 5 or 6 for the bookish asks, if you feel like answering them? :)

From this bookish ask meme, thank you so much!

6. Which book was the last one that you really, really loved?

Either Natalie Haynes’ ‘A Thousand Ships’ - a retelling of the Trojan War from the perspective of the women who are forgotten and/or have their stories misconstrued or marginalised in Homer and Virgil’s epics or ‘Seashaken Houses A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet’ by Tom Nancollas

Quotes from both:

‘This was never a story of one woman, or two. It was the story of all of them. A war does not ignore half the people whose lives it touches. So why do we?’ - A Thousand Ships: Natalie Haynes

‘Longplayer challenges us to remain interested, to maintain our interest as the centuries pass, measuring the value we place on endurance’ - Seashaken Houses: Tom Nancollas

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

tagged by the lovely @gothyringwald <3

favourite colour: Dark green.

last song: A Message To My Future Self - JER

last movie: Apostle (2018) dir. Gareth Evans

watching:Bridgerton (finally!)

reading: Piranesi - Susanna Clarke, Paper Girls - Brian K Vaughan & Cliff Chiang, Seashaken Houses: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet - Tom Nancollas.

sweet, spicy, or savoury: Savoury

tea or coffee: Tea!

favourite drink: Tea or tap water.

Aaaaaaand I’m going to tag @old-long-john, @angst-wizard, @anyone else who wants to do it.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seashaken Houses: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet

Seashaken Houses: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet by Tom Nancollas

'A thrilling celebration of lighthouses' i newspaper

An enthralling history of Britain's rock lighthouses, and the people who built and inhabited them

Lighthouses are enduring monuments to our relationship with the sea. They encapsulate a romantic vision of solitary homes amongst the waves, but their original purpose was much more noble, conceived as navigational gifts for the safety of all. Still today, we depend upon their guiding lights for the safe passage of ships. Nowhere is this truer than in the rock lighthouses of Great Britain and Ireland: twenty towers built between 1811 and 1904, so-called because they were constructed on desolate, slippery rock formations in the middle of the sea, rising, mirage-like, straight out of the waves, with lights shining at the their summits.

Seashaken Houses is a lyrical exploration of these magnificent, isolated sentinels, the ingenuity of those who conceived them, the people who risked their lives building and rebuilding them, those that inhabited their circular rooms, and the ways in which we value emblems of our history in a changing world.

Download :

Seashaken Houses: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet Seashaken Houses: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet

More Book at:

Zaqist Book

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Seashaken Houses by Tom Nancollas review – a hymn to the lighthouse keepers https://ift.tt/2DF548v

0 notes

Text

Fortnite is secretly great for Lighthouse Roulette • Eurogamer.net

I have a question about Fortnite’s lighthouse. How does it work? There’s a light at the top, but little in the way of machinery or power sources. I wondered if the house near the lighthouse might serve as some kind of generator, but if it does it’s well concealed. Just another mystery in an island of mysteries, then. What keeps the light shining?

This is the mystery that drew me back to the lighthouse earlier this week. I’ve been reading Seashaken Houses, Tom Nancollas’ evocative tour of England’s rock lighthouses and I started wondering about the intricacies of Fortnite’s lamp. This was stupid, of course, but it doesn’t matter, because while I was off on my stupid adventure I discovered something brilliant. It’s almost a new game mode.

Do you remember Loot Lake? Loot Lake was a house sat in the middle of a lake, and it was brilliant because the same thing always happened at the start of each match. Two people would generally aim for the lake, because it was lovely, and one would end up in the attic and the other would end up in the house below. Maybe the person in the attic got a treasure chest. Maybe not. Whatever they found up there, Loot Lake would be gripped by two people living in the same space, a drama that could play out in any number of ways.

youtube

I got to thinking of it as Loot Lake Roulette. The attic was where I wanted to be, but it was so risky – hard to defend, and perhaps completely empty when it came to weaponry. A gamble!

So anyway, earlier this week I landed at the lighthouse. I normally land on the roof and work my way down, but I was being methodical this time so I landed outside and worked my way up. Inside the lighthouse is a tight coil of stairs with weapons and treasure chests generally scattered about. Halfway up the stairs I realised that, chances are, there was someone on the roof. There is almost always a chest on the roof, but also it’s just such a pleasant thing to land on people find it hard to resist. I suddenly realised that I was probably heading up to a confrontation. And it reminded me of those old Loot Lake moments, those moments I miss so much. Someone downstairs, someone upstairs. Who wins?

Except with the lighthouse it’s even better. For one thing, the place is generally stuffed with weaponry. For another, there’s almost no space so you’re going to have to think fast. For another final thing, that staircase is long, man. A lot of time to think about what lies ahead.

I have played Lighthouse Roulette several times now. Early results suggest that it’s much better to land on the roof, but that it’s much more thrilling to land downstairs and do the climb. I think there’s something very potent about Fortnite lurking in here. This is a game that has exploded the number of ways you can play, the number of personal objectives and ambitions you can hold in your mind. Where next?

from EnterGamingXP https://entergamingxp.com/2019/12/fortnite-is-secretly-great-for-lighthouse-roulette-%e2%80%a2-eurogamer-net/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=fortnite-is-secretly-great-for-lighthouse-roulette-%25e2%2580%25a2-eurogamer-net

0 notes

Quote

Longplayer challenges us to remain interested, to keep the inclination to maintain our interest as the centuries pass, measuring the value we place on endurance.

Tom Nancollas, Seashaken Houses (2017)

1 note

·

View note