#USITC

Text

How tech does regulatory capture

If you want to know which industries have the most influence in DC, study the trade deals struck by the US Trade Representative, whose activities are the most obvious manifestation of American corporate power over state. Take the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). As David Dayen notes, this treaty is a kind of Big Tech wishlist:

https://prospect.org/power/2023-04-18-big-tech-lobbyists-took-over-washington/

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/18/cursed-are-the-sausagemakers/#how-the-parties-get-to-yes

The USTR’s playbook has changed over the years, reflecting the degree of control over the US government exerted by different sectors of the US economy. Today, with Big Tech in the driver’s seat, US trade deals embody something called the “digital trade agenda,” a mix of policies ranging from limiting liability, privacy protection, competition law, and data locatization.

The Digital Trade Agenda is a relatively new phenomenon. A decade ago, when the USTR went abroad to twist the arms of America’s trading partners, the only “digital” part of the agenda was obligations to spy on users and to swiftly remove materials claimed to have violated US media monopolies’ copyright. But as the tech sector grew more concentrated, they were able to seize a greater share America’s trade priorities.

One person who had a front-row seat for this transformation was Wendy Li, a PhD candidate in sociology at the University of Wisconsin, who served in the USTR’s office from 2015–17, and who leveraged her contacts among officials and lobbyists (and ex-lobbyists turned officials and vice-versa) to produce a fascinating, ethnographic account of a very specific form of regulatory capture. That account appears in “Regulatory Capture’s Third Face of Power,” in Socio-Economic Review. The article is paywalled, but if you access it via this link, you can bypass the paywall:

https://pluralistic.net/wendi-li-reg-capture

Li’s paper starts with a taxonomy of types of regulatory capture, drawn from the literature. The first kind — the “first face of power” — is when an industry wins some battle over a given policy, triumphing over the public interest. Li notes that defining “public interest” is sometimes tricky, which is true, but still, there are some obvious examples of this kind of capture.

My “favorite” example of horrible regulatory capture is from 2019, when Dow Chemical — working through the West Virginia Manufacturers Association — convinced the state of West Virginia to relax the limits on how much toxic runoff from chemical processing could be present in the state’s drinking water. Dow argued that the national safe levels reflected a different kind of person from the typical West Virginian. Specifically, Dow argued, the people of West Virginia were much fatter than other Americans, so their bodies could absorb more poison without sickening. And besides, Dow concluded, West Virginians drink beer, not water, so poisoning their drinking water wouldn’t affect them:

https://washingtonmonthly.com/2019/03/14/the-real-elitists-looking-down-on-trump-voters/

This isn’t even a little ambiguous. Dow’s pleading wasn’t just absurd on its face — it was also scientifically bankrupt — there’s no evidence that being overweight makes you less susceptible to carcinogens. And yet, the state regulator bought it. Why? Well, maybe because chemical processing is WV’s largest industry, and Dow is the largest chemical company in the state. Regulatory capture, in other words.

The second kind of regulatory capture is the “revolving door”: when an executive from industry rotates into a role in government, where they are expected to guard the public interest from their former employers. There’s some of this in every presidential administration — think of Obama’s ex-Morganstanley and ex-Goldmansachs finance officials.

But while Obama and other “normal” pols sketched their corruption with a fine-tipped pen, making the overall shape hard to discern, Trump scrawled large, crude, unmissable figures with a fisted Sharpie. Remember Scott Pruitt, the disgraced Trump EPA who wanted to abolish the EPA? Pruitt was was such a colossal asshole that even the lobbyists who’d been bribing him with free housing actually evicted him:

https://www.cnn.com/2018/04/06/politics/pruitt-trump/index.html

After Pruitt resigned in the midst of chaotic scandal, he was succeeded by his deputy, Andrew Wheeler — a former coal lobbyist:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/05/climate/scott-pruitt-epa-trump.html

That’s the “second face of power.” What’s the third? It’s taking over the shape of the debate, getting to define its axioms. Think of the reflexive idea that government projects are “wasteful” and “inefficient.” Once all players internalize this idea, the debate shifts from “what should the public sector do?” to “which private-sector entity should the government pay to do this?” Anyone who says, “Wait, why doesn’t the government just do this?” just gets blank stares.

We can see this in the cramped and inadequate debate over the SVB bailout; apologists for the bailout insist that it was necessary because if SVB’s depositors had been forced to take a haircut, every large depositor in America would pile into Morganstanley, making it so “too big to fail” that it could tank the nation.

This is probably true — but only if you discount the possibility of establishing a public bank. Public banks are hardly a radical idea: America had nationwide public banking through the postal service until 1966:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/04/15/socialism-for-the-rich/#rugged-individualism-for-the-poor

Li summarizes: “the first face of power is measured through the winner of the game, and the second face of power can be understood as the referee. The third face of power is the field, the rulebook, and agreement that there is even a game at all.”

It’s the creation of this third face that Li’s paper dissects — the creation of “Type I” ideas that form the unquestioned assumptions for all other debate. Sociologist call these ideas “schemas.” Li describes two ways that the tech industry changed the schemas used in trade negotiations. First, schemas are changed through “knowledge production” — creating reports and data.

Second, schemas are embedded through “recursive institutional reproduction” — a bit of unfortunately opaque academic jargon that is roughly equivalent to what activists call “policy laundering.” That’s when an industry can’t get its way in its home country, so it leans on trade reps to include that policy in a treaty or trade deal, which transforms it into an obligation at home.

In tech policy, the Ur-example of this is the DMCA, a 1998 digital copyright law that has profoundly changed the way we relate to everything from online services to our coffee makers. The origins of the DMCA are wild. In 1991, Al Gore kicked off the National Information Infrastructure hearings — AKA the “Information Superhighway” project. One of the most prominent proposals for the future of the internet came from Bruce Lehman, Bill Clinton’s Copyrigh tCzar. Lehman had been the head of IP enforcement for Microsoft, and he had some genuinely batshit ideas for the internet, like requiring a separate, negotiated copyright license for every transitory copy made by RAM, or a network buffer, or drive cache:

https://www.wired.com/1996/01/white-paper/

Gore laughed Lehman out of the room and told him to hit the road. So Lehman did, scurrying over to Geneva, where he turned his batshit ideas into the WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT) and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty (WPPT). Then he raced back to DC where he told Congress that they had to get on board with those UN treaties. In 1998, Congress passed the DMCA, turning a failed regulatory policy into a federal law that endures to this day.

That’s “policy laundering.” Lehman couldn’t get his ideas though the US government, so he rammed them through a UN agency, converting his proposal into an obligation, which Congress duly assumed.

The Digital Trade Agenda triumphed by both knowledge production and recursive institutional reproduction (AKA policy laundering). Under Obama, trade officials created the Digital Trade Working Group in consultation with industry, through the US Chamber of Commerce. This group worked with the US International Trade Commission (USITC) — a quasi-governmental research body — to produce copious reports, testimony and data in support of a focus on “digital trade.”

In particular, they inflated the value of digital trade to US officials, convincing them that getting wins for the digital industry would have an outsized impact on the US economy. This is reflected in the terms of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade deal that was negotiated in the utmost secrecy, in hotels all over the world surrounded by armed guards, where neither the press nor activists were welcome.

TPP represented a kind of farcical wishlist for America’s corporate giants, including the tech sector, and it looked like a done deal — until Trump. Trump unilaterally withdrew from TPP, so the tech industry’s reps simply tacked around TPP. They took everything they’d wanted to get out of TPP and crammed it into the USMCA, Trump’s rewrite of NAFTA. This makes perfect sense — corporate America’s priority was TPP’s policies, not TPP itself.

Li’s paper doesn’t just document this shift, she also gives us interviews with (anonymized) officials and lobbyists who speak frankly about how this happened behind the scenes. For example, a former Commerce official turned tech lobbyist describes how he lobbies his former coworkers: “Sometimes, [meetings are like] hey, let’s grab lunch, let’s grab coffee, and catch up. And half of it is about our kids, and half of it is about this [work related issue]. We’ll have a formal meeting [with government officials], but obviously we chitchat before and after. Because we’re human. So, a lot of it is just normal human interaction, right?”

This social coziness lets lobbyists position themselves as “stakeholders,” which legitimizes — and even requires — their participation in policymaking. As a trade negotiator says, “So to get your handle on a problem, you’ve got to pull the right people together, and you’ve got

to sift through all the various ideas, so we obviously have a lot of regular interaction with companies [. . .] I spend a lot of time with the companies trying to understand their business model, try ing to understand how they interact with the governments in different countries, and then of course, socializing it within the building.”

Once lobbyists are “stakeholders,” they get to define not just what position the US takes — they get to define which positions can even be considered. As a trade negotiator says, “[Lobbyists aren’t] coming in and spouting talking points. They’re not giving us draft text because

we haven’t gotten to the text phase yet. The way these meetings go is, generally we provide an update on what is happening and what approach we’re taking. The remainder is usually devoted to companies talking about their particular interests, and inquiring as to whether and how their issues are being addressed in that forum.”

That’s not just winning the game — it’s defining the rules.

Li’s paper is a fascinating tour of the sausage-factory and a close examination of the gunk that litters the factory floor. That said, I think there are areas where she drops policies and fights into neat categories that are much messier. For example, Li contrasts the rules in TPP with the rules in ACTA, the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, a failed international treaty from 2010.

Li characterizes ACTA as being an anti-tech proposal because it imposed copyright liability on tech companies, which would have raised their costs by forcing them to police their users’ speech, items for sale and uploads for copyright infringement. But that’s not quite right: ACTA was much broader. First, because “counterfeiting” doesn’t mean what you think it does: in an international trade agreement, counterfeiting concerns itself with all kinds of totally legitimate activities.

For example, Apple engraves microscopic Apple logos on every part in an iPhone; no user ever sees these parts. But Apple uses the presence of an Apple trademark on these tiny components to lodge trademark claims with US border officials in order to block the importation of parts harvested from dead iPhones, as part of the company’s war on repair:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/05/30/80-lbs/#malicious-compliance

Likewise, companies like Rolex and Cartier have national subsidiaries in countries all over the world with the exclusive license to sell their goods in each country. These companies then claim that, say, an official Mexican Rolex watch becomes a counterfeit Rolex the minute it crosses the US border, because Rolex Mexico doesn’t have the right to use Rolex International’s trademarks outside of Mexico.

Asking tech companies to police “counterfeits” isn’t just about stopping knockoffs — it’s about letting multinational corporations control all secondary markets for their goods, giving them total control over repair and used goods.

Beyond that: creating an affirmative duty for platforms to police their users’ uploads and speech for copyright infringement is one of those things that not only won’t prevent copyright infringement (beating filters is easy for dedicated copyright infringers), but it will also compromise users’ speech (because filters are rife with false positives) — and it will hand eternal dominance to the largest tech firms (both Youtube and Facebook support mandatory filters, because they’ve spent hundreds of millions on them, and know that their small rivals can’t).

ACTA wasn’t a way to “punish” tech to make life better for media companies — it was a way to shift some of the oligarchic control of both tech and media around, while shoring up its dominance. Yes, parts of the tech sector hated ACTA, but it died because millions of people campaigned against it.

And of course, ACTA got policy-laundered into law in 2019, when the EU adopted the Digital Single Market Directive and created a filtering mandate, ignoring the largest petition in EU history and the people who marched in 50 cities. That was recursive institutional reproduction in action all right.

Likewise, TPP can’t be understood as the tech sector sidelining the entertainment companies — because both of them rallied for the parts of TPP that feathered all their nests. For example, the entertainment sector and the tech sector both love rules against reverse-engineers (like Section 1201 of the DMCA), which make it a felony to unlock your books, music, games and videos from the store that sold them to you and take them with you to another player.

Tech loves this because it gets them lock-in — if you break up with Amazon, you have to kiss your Kindle and Audible books goodbye. Media loves it because it gives them control — DRM stops you from recording Christmas movies between Feb and Dec, when they come free with your streaming service, and that means you have to pay-per-view them in December, when you want to watch them.

In other words, the Big Tech and Big Content’s policy fights aren’t so much about which policies we get — they’re about who gets to profit from them. They both want the same stuff — no taxes, no unions, no minimum wage, no consumer rights, no privacy — but they each want to hoard the benefits from that stuff.

Both tech and media love “IP” — not in the sense of “copyright” or “trademark,” but in the sense of “any law that lets me control the conduct of my competitors, critics and customers”:

https://locusmag.com/2020/09/cory-doctorow-ip/

In USMCA, it wasn’t just the “Digital Trade Agenda” that made it into the final agreement — it was mandatory DRM laws, massive copyright extensions, and the evisceration of fair use and its equivalents in Mexico and Canada:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/08/01/set-healthy-boundaries/#la-ley

There’s another important factor missing from Li’s analysis of the rise of the Digital Trade Agenda: monopoly. Tech used to be composed of hundreds of competing firms that hated each other’s guts and were incapable of working together. The entertainment industry, by contrast, was already hugely consolidated and able to lobby effectively as a body.

That was hugely important in the Napster Wars, when international copyright proposals like the Database Right and the Broadcast Treaty were popping up at the UN and in country-to-country trade deals. While the tech industry was competing to give users a better deal, Big Content was able to solve the collective action problem and come up with a common lobbying position, getting nearly identical (and absolutely ghastly) tech bills introduced in dozens of state legislatures at once:

https://web.archive.org/web/20030425210736/https://www.eff.org/IP/DMCA/states/200304_sdmca_eff_analysis.php

The rise of the Digital Trade Agenda is downstream of tech industry consolidation, the orgy of mergers that saw the internet transformed into “five giant websites, each filled with screenshots of text from the other four”:

https://twitter.com/tveastman/status/1069674780826071040

Li’s taxonomy of regulatory capture is useful and important, and it’s complimented by an analysis of failures in antitrust enforcement. Market consolidation has produced firms that are more powerful than the governments that are supposed to keep them honest. When the teams have more power than the ref, the game will never be fair:

https://doctorow.medium.com/small-government-fd5870a9462e

The tech industry aren’t really adverse to the entertainment industry, at least not where it counts. They are all part of the business lobby, whose regulatory priorities are broadly shared, even if they disagree at the margins. Dayen describes how the Digital Trade Agenda is playing out in IPEF, the treaty with more than a dozen Pacific Rim countries: “It would prohibit governments from reviewing or prescreening algorithms for violations of labor law, competition policy, or nondiscrimination statutes. It would bar limitations on data flows or storage. And it would treat policies that have greater impacts on the large tech firms as illegal trade barriers. These terms could block signatory countries from writing laws that take on any of these issues.”

Those aren’t tech priorities — those are corporate priorities. The success of the “Digital Trade Agenda” isn’t just because tech grew up and started lobbying — it’s because the things they lobby for are the things every business wants: no labor protection, no antitrust, no privacy.

That’s the “schema” that matters: the bedrock assumption that job of US trade policy is to make sure that workers and residents abroad have no rights, with the obligation on America to dismantle the few rights that remain intact in its borders to satisfy the “obligation” it actually insisted on.

Later this week (Apr 20/21), I’m speaking in Chicago at the Stigler Center’s Antitrust and Competition Conference.

This weekend (Apr 22/23), I’m at the LA Times Festival of Books.

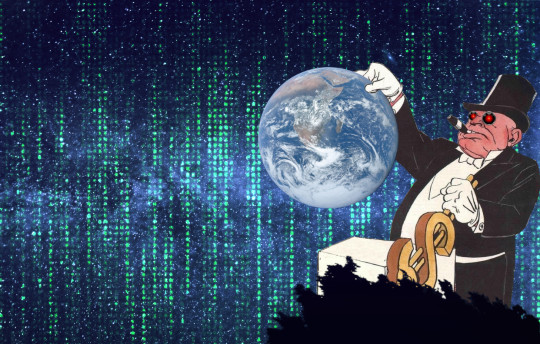

[Image ID: The Milky Way. Standing to the left of the frame is a giant ogrish figure, a top-hatted, cigar-chomping caricature of a capitalist. He emerges from behind a silhouetted tree, towering over it. With one white-gloved hand, he is yanking a golden, dollar-sign-shaped lever at a control box. With the other hand, he disdainfully dangles a 'big blue marble' image of Earth from space. The starry sky is partially blended with a green-on-black 'code waterfall' effect in the style of the Matrix movie open credits. The ogre's eyes have been replaced with the glaring red eyes of HAL9000 from Stanley Kubrick's '2001: A Space Odyssey.']

Image:

Cryteria (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

—

Andy (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Milky_Way_and_Andromeda_Galaxies.jpg

CC BY 2.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#us trade representative#scholarship#regulatory capture#wendy li#ustr#usmca#digital trade policy#trade#anti-counterfeiting trade agreement#us canada mexico agreement#US International Trade Commission#USITC#copyfight#collective action problems#collusion#monopoly#big tech#how the sausage gets made#ipef#Indo-Pacific Economic Framework#thanks obama#Digital Trade Working Group#ethnography#third face of power

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gli Stati Uniti decideranno a marzo sui dazi sui pneumatici dalla Thailandia

Il Dipartimento del Commercio degli Stati Uniti sta indagando sulle importazioni di pneumatici per autocarri e autobus dalla Thailandia dopo che la Commissione per il commercio internazionale degli Stati Uniti (USITC) ha accolto una petizione presentata dal sindacato United Steelworkers (USW) il 17 ottobre 2023.

L’USITC ha stabilito il 30 novembre che l’industria nazionale dei pneumatici è…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Apple запретили продажи умных часов в США

Американские продажи новых умных часов Apple Watch запретили. Комиссия по международной торговле США (USITC) запретила корпорации Apple продажи умных часов из-за проигранного патентного спора с компанией Masimo. С 25 декабря экспорт Apple Watch 9 и Apple Watch Ultra 2 в страну будет запрещен.

Подробнее https://7ooo.ru/group/2023/12/19/469-apple-zapretili-prodazhi-umnyh-chasov-v-ssha-grss-266393349.html

0 notes

Text

USITC hears testimony on GHG emissions intensity of U.S.-produced aluminum, steel

Read the full story in Recycling Today.

In July, the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) began a fact-finding investigation, Greenhouse Gas Emissions Intensities of the U.S. Steel and Aluminum Industries at the Product Level, Inv. No. 332-598, to assess the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions intensity of steel and aluminum produced in the United States. The investigation was requested by the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Data Center Market

The Data Center Market size is estimated to reach $418 billion by 2030, growing at a CAGR of 9.6% during the forecast period 2023-2030. The advantages of Data Centers include hyper-scalability, sustainability and automation for modern business processes. It is set to propel the demand for Data Centers during the forecast period. According to USITC, as of 2022, there are approximately 8000 physical data centres present across the globe.

0 notes

Text

The recent “definitive victory” by AVD was a critical win for the US cannabis industry. Alex Kwon, Founder and CEO of AVD discusses USITC cannabis vaping dispute, Wartime CEO strategies, Building a Diversified Supply Chain and more. Listen to the Dime podcast or read the transcripted version at The Eighth Revolution to know more.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Urea Ammonium Nitrate Solutions from Russia and Trinidad and ... - USITC

Urea Ammonium Nitrate Solutions from Russia and Trinidad and ... USITC http://dlvr.it/Sjhl6l

0 notes

Text

USITC Investigations, St. Louis Cardinals, Twitter, More: Monday Afternoon ResearchBuzz, January 16, 2023

NEW RESOURCES

United States International Trade Commission: USITC Launches New Investigations Database System . “The United States International Trade Commission (USITC) today deployed the Investigations Database System (IDS), an innovative new data management tool that captures, manages, and displays USITC investigation-related information…. A major new feature is the ability to conduct quick…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

A New York Times Bestseller Has Been Accused of Plagiarism

A New York Times Bestseller Has Been Accused of Plagiarism

– Bell Semiconductor LLC has filed a complaint with the US International Trade Commission (USITC) alleging violations of the Tariff Act of 1930 involving semiconductor devices having layered dummy fill and electronic devices.

– The semiconductors, which are being imported into and sold in the US, allegedly infringe one patent.

– The USITC has voted to investigate the allegations and has requested…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Qualcomm e TSMC per presunta violazione di brevetto.

La US International Trade Commission sta indagando su Samsung, Qualcomm e TSMC per presunta violazione di brevetto.

Le grandi multinazionali sono costantemente alle prese con sfide legali, e questo è più vero per le aziende del settore tecnologico rispetto ad altre, perché i brevetti che vengono registrati in questo settore creano sempre margini e i proprietari apple di questi documenti di brevetto da difendere Faranno di tutto per i loro diritti.

Samsung ha una lunga storia di battaglie legali sui brevetti, il cui esempio più famoso è stata la sfida pluriennale dell'azienda coreana con Apple. Oltre a questi, gli organismi di regolamentazione del governo hanno ripetutamente interrogato Samsung. Come scrive SamMobile, la Commissione per il commercio internazionale degli Stati Uniti (USITC) sta indagando su Samsung.

0 notes

Link

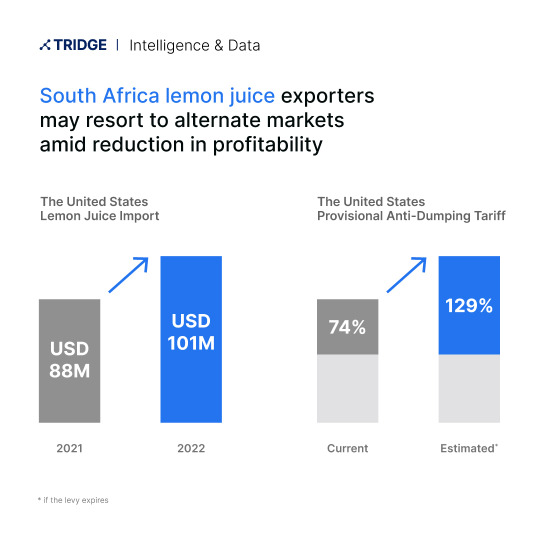

United States is the largest importer of lemon juice. South Africa processes about 20% of their citrus to make lemon juice. If levy expires, the anti-dumping tariff on South African lemon juice is expected to be 129%.

0 notes

Text

Hondas, LG Batteries Announce $3.5 Billion Investment in Ohio Battery Plant

New Post has been published on https://medianwire.com/hondas-lg-batteries-announce-3-5-billion-investment-in-ohio-battery-plant/

Hondas, LG Batteries Announce $3.5 Billion Investment in Ohio Battery Plant

With Honda beginning to take the path of full electrification for their U.S. models, the Japanese automaker needed a battery plant local to their facilities. Now, LG Energy Solutions and Honda have formed a joint venture to build a battery plant just an hour south of their R&D center in Raymond, Ohio, to supply Honda with the batteries it needs for its future BEV models, like the 2024 Honda Prologue being codeveloped with GM (which, incidentally, happens to use GM’s Ultium battery technology manufactured in a joint venture with LG).

LG and Honda have reached an agreement to build a new battery plant in Fayette County. Each company is investing $3.5 billion in total towards the JV, but it’s projected to eventually total $4.4 billion before completion. The construction of the facility should begin in early 2023, and if everything stays on schedule, the plant will be completed in 2024. By 2025, it should build around 40 GWh (gigaWatt hours) of battery capacity annually of lithium-ion pouch-type cells. That’s around the timeframe of when Honda will begin producing and selling its own electric vehicles for the U.S. By 2026, Honda’s e:Architecture will be fully developed and production would need to begin by 2025 or so.

For LG, the Honda joint venture will add to its growing U.S. constellation of battery facilities and partnerships. As recently as just a year ago, Stellantis and LG proposed a JV for a battery plant in North America while GM’s Ultium batteries are all produced by LG. It looks like LG is becoming the most recent big player in the EV battery market, especially since SK Innovations has had some trouble last year with the U.S. International Trade Commission. The USITC set a 10 year exclusion order that prohibits SK from importing its lithium-ion EV batteries in the U.S. after LG filed a complaint that SK stole EV battery trade secrets from it.

Read the full article here

0 notes

Text

Knock off crocs

#KNOCK OFF CROCS TRIAL#

The patent had previously been rejected three times by the USPTO after a dispute was filed by one of Crocs’ competitors, USA Dawgs. he knocked a stack of papers over as he turned toward it. Our team will contact you with more information in 1-3 business days to make your customized Classic Clogs and Jibbitz charms a reality.

#KNOCK OFF CROCS TRIAL#

Patent and Trademark Office’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board held that the design patent for the Classic Crocs clog was valid. No, Spivey said, picking up a magazine off the nearest pile. The USITC voted in favor of pursuing the investigation.Ĭrocs landed a long-sought victory in September 2019 when the U.S. District Courts, followed Crocs’ complaint in June 2021 with the United States International Trade Commission (USITC) requesting an investigation into the unlawful import and sale of allegedly infringing footwear. as well as many lesser-known companies that sell online - or wholesale to retailers such as Walmart. The 10 Best Crocs and Crocs Knockoffs Fashion By Andrea Pyros Crocs is celebrating its 20th anniversary in 2022, so it’s the perfect time to purchase a new pair of the beloved and sometimes controversial shoes to add to your Crocs collection. floor of a modern retirement high-rise, just off Weber Road, north of Joliet. Crocs can also be worn with a baggy denim shirt and a perfectly matching cap, but keep in mind they suit the rest. Crocs also look good with half leggings, jackets, and shorts. Crocs go well with denim shorts and high-ankled pants, which draw attention to the shoe’s design. The defendants included Walmart Inc., Loeffler Randall Inc. wearing a Sunset Boulevard T-shirt, green sweat pants, and pink Crocs. Dress up your Crocs with high waisted pants to showcase their charm. Last July, Crocs filed lawsuits against 21 companies for allegedly infringing on its trademarks. The filing marks the latest attempt for Crocs to curb copycat designs of its classic clog, a silhouette that has surged in popularity during the Covid-19 pandemic. Daiso could not immediately be reached for comment. “This infringement and dilution scheme is intended to confuse, deceive, and mislead consumers into drawing associations between Crocs and Daiso and their respective footwear products so that Daiso can enjoy unfair gains and profits at the expense of Crocs,” Crocs alleged.įN has reached out to Crocs for a comment. Earnings Wrap: Gap Reports Latest Results + More

0 notes

Text

US orders on PSF import from S Korea, Taiwan to remain in place

The US International Trade Commission (USITC) recently concluded that revoking the existing anti-dumping duty orders on import of polyester staple fibre (PSF) from South Korea and Taiwan would likely lead to continuation or recurrence of material injury within a reasonably foreseeable time. As a result, the existing orders on import of this product from the two economies will remain in place.

The action came under the five-year (sunset) review process required by the Uruguay Round Agreements Act, which requires the US department of commerce to revoke an anti-dumping or countervailing duty order, or terminate a suspension agreement, after five years unless the department and the USITC determine that doing so would likely lead to continuation or recurrence of dumping or subsidies and of material injury within a reasonably foreseeable time.

Read more about US orders on PSF import from S Korea, Taiwan to remain in place

Explore Textile Import Export News

0 notes