#Vivant Denon Museum

Text

A fragment of a yellow coffin. We can make out the deceased offering incense and other goodies to Osiris, who kneels on a nub-symbol behind his imuit-fetish.

When: Third Intermediate Period, 21st/22nd Dynasty

Where: Vivant Denon Museum

#Ancient Egypt#coffin#yellow coffin#Osiris#Vivant Denon Museum#Third Intermediate Period#21st Dynasty#22nd Dynasty

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon and the Bayeux Tapestry

In 1803-1804, this tapestry was borrowed from Bayeux in Normandy for a two-month exhibition at the Musée Napoléon (Louvre).

Vivant Denon’s letter to the sub-prefect of Bayeux the following year:

“I am sending back to you the Tapestry embroidered by Queen Matilda, wife of William the Conqueror. The First Consul has seen with interest this precious monument of our history, he has applauded the care that the habitants of the city of Bayeux have brought for seven and a half centuries to its conservation. He has charged me to testify to them all his satisfaction and to entrust them with the deposit. Invite them to bring new care to the conservation of this fragile monument, which retraces one of the most memorable actions of the French Nation.”

(20 February 1804)

Napoleon attended the opening of the exhibition on 5 December 1803, with Denon and Visconti.

A press release for the exhibition was published in the ‘Beaux-Arts’ column in Le Moniteur on 29 November and in the tabloid Journal de Paris on 28 November. Visconti wrote a guide for the artwork which was partially reprinted in Le Moniteur.

The tapestry was returned to Bayeux two months later, on 18 February 1804. Many in Paris wanted to keep it in the city, but Napoleon ordered that it be returned.

Previously, the historic tapestry had been confiscated during the French Revolution. It was covering military wagons and almost cut up when a local lawyer, Léonard Lambert-Leforestier, saved it by sending it to city administrators for safekeeping.

The tapestry depicts the William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy. The piece was made about a decade after his 1066 invasion of England and the purpose of the tapestry was to glorify the invasion.

It was displayed to the public in Bayeux in 1812 and has been publicly displayed ever since:

“From 1812 the Tapestry was kept in the Hotel de Ville (city hall) in Bayeux. It was generally hung and displayed to the public in September of every year. In addition, the custodian could show it to visitors, rolling it out gradually on a table by turning the crank handle of a winder: this way of exhibiting it was described on several occasions by British writers between 1814 and 1836. From 1842, it was put on permanent display for the first time in the Matilda gallery.”

Sources:

Susan Jaques, The Caesar of Paris: Napoleon Bonaparte, Rome, and the Artistic Obsession that Shaped an Empire

Carola Hicks, The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life Story of a Masterpiece

Bayeux Museum: From Odo’s Cathedral to the Louvre

#Bayeux Tapestry#Bayeux#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic#napoleonic era#first french empire#french empire#19th century#william the conqueror#France#history#art#norman invasion#1066#Susan Jaques#Carola Hicks#The Caesar of Paris#The Caesar of Paris: Napoleon Bonaparte Rome and the Artistic Obsession that Shaped an Empire#Vivant Denon#Denon#tapestry#embroidery#tapestries#Middle Ages#medieval#medieval history#french history#louvre

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The fate of Sainte Apolline

A friend sent me a link to this video about Napoleon’s marshals Suchet, Ney and Soult that, as far as Soult is concerned, of course inevitably had to refer to Soult’s avarice and his looting of Spanish art.

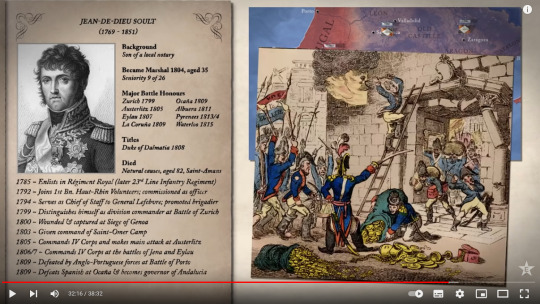

In order to visualize the looting, there is this picture (screenshot at 32:16):

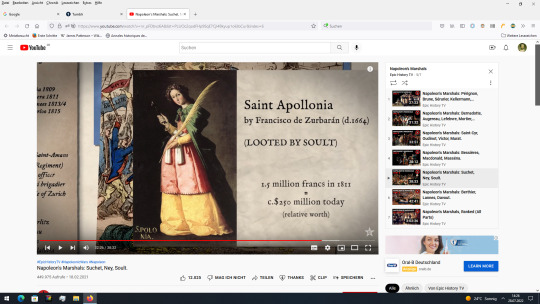

And we even get an example of stolen artwork: »Sainte Apolline« by Zurbaran (a couple of seconds later):

Which I consider a nice opportunity to look into the matter a little more closely.

Before the French occupation of Spain, the painting in question belonged to the catholic order »San José de la Merced Descalza« and presumably was part of its church. That order, like all male monastic orders in the whole of Spain, was dissolved by decret of newly installed king Joseph Bonaparte in 1810, all its properties falling to the government. So »Sainte Apolline« was, together with an abundance of other paintings from other convents, brought to the Royal Alcazàr, the official residence of king Joseph in Sevilla.

Just to make sure: No, Soult (or rather his men) did not loot those paintings out of his own volition and for his own good. He seized them in the name and for the person whom his emperor had told him was the new king of Spain, Joseph Bonaparte.

To my knowledge, there also never was any actual fighting or looting taking place in Sevilla, at least not in the way that is pictured in the caricature above. I understand king Joseph entered the city quite peacefully, stayed a couple of weeks and then immediately hurried back to his mistresses in Madrid, leaving the work that was to be done to Soult (and complaining behind Soult’s back to Napoleon about him). By the way, as far as actual »looting« is concerned, not even Soult’s enemies in France (which seem to have been much more ferocious than outside of France) denied that all the paperwork was in order. He had certificates and receipts for each and every of his paintings.

But of course, these papers had to cover up a forced trade that Soult had imposed on the former owner through threats of reprisals, torture, and death. Right?

At least in the case of Sainte Apolline we can rule that out. Or at least, if Soult indeed stole the painting, he stole it from King Joseph. But that was probably not even necessary, as Soult’s penchant for art was obviously well-known and offered Joseph a rather cheap way of rewarding Soult for his services: just hand him over half a dozend of those hundreds of paintings catching dust in the Alcazàr whenever the guy gets testy.

But back to »Sainte Apolline«: The text next to the painting in the screenshot makes it look as if this painting alone had been worth 1.5 million Franc in 1811. That is not what the speaker in the video says, however, who claims that Soult »amassed an art collection worth an estimated 1.5 million Francs«.

Which, unfortunately, still is incorrect. First of all, this is not an estimation – it is the actual worth of Soult’s collection of art that was on sale after his death, consisting of 163 works of art (see the catalogue here), and with one third of the sum going to a single painting, the »Inmaculada Concepcion de los venerables« by Murillo. But most of all, this happened in 1852, four decades later! Those four decades mean a lot here. Because at the time when Soult acquired the paintings (by whatever means) they were considered so unimportant that Vivant Denon refused most paintings Joseph offered to him for the Louvre and kept haggling for the very few he considered worthy of a Paris museum, but that Joseph wanted to keep in Spain. At the time when Soult bought his paintings, with all convents dissolved and an abundance of religious art on the market all of a sudden, the price for paintings must have dropped close to zero. The paintings also often were in very bad shape and desperate need of restauration. Soult writes to his wife that he actually bought a painting somewhere on the docks, where they were stored in the open.

»Sainte Apolline«, btw, stayed in Soult’s family even after his death. According to the description of provenience on the website of the Louvre, it was his daughter Hortense de Mornay who bought it, and only after her death was it acquired by the Louvre. Who probably could have had it a lot cheaper in 1810 or 1811.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

An exceptional dagger with broad rondels,

OaL: 19.9 in/50.5 cm

recovered from the River Saône, France, 15th century, housed at the Vivant-Denon Museum.

#weapons#dagger#rondel dagger#europe#european#french#france#medieval#middle ages#vivant-denon musuem#art#history

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Adoration of the Shepherds, Dominique Vivant Denon, 18th century, Harvard Art Museums: Prints

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Belinda L. Randall from the collection of John Witt Randall

Size: Image: 48.2 × 38.6 cm (19 × 15 3/16 in.) Plate: 52.7 × 42.5 cm (20 3/4 × 16 3/4 in.) Sheet: 59.5 × 48 cm (23 7/16 × 18 7/8 in.)

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/239422

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Funerary monument of Dominique Vivant Denon (1747-1825) by Pierre Cartellier (1757 – 1831) at Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris.

Vivant Denon was the first Director of the Louvre Museum (called Musée Napoleon at the time) from 1802 until 1816.

#mine#Funerary monument#Dominique vivant denon#Pierre Cartellier#Père Lachaise cemetery#cimetière père lachaise#paris#19th century#sculpture#art#director#louvre museum#musée napoleon#rose#flower#tomb#photography#18th century#napoleonic era

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rembrandt Peale – Scientist of the Day

Rembrandt Peale, a Philadelphia portrait painter, was born Feb. 22, 1778.

read more...

#Rembrandt Peale#portrait painters#mastodons#mammoths#fossils#histsci#histSTM#19th century#history of science#Ashworth#Scientist of the Day

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The first depiction of Napoleonic melancholy...”

Excerpts from Jean-Paul Kauffman’s The Dark Room at Longwood on Antoine-Jean Gros’s famous painting, Napoleon on the Battlefield of Eylau (also known as The Eylau Cemetery):

***

Delacroix claims that “It is the most magnificent and most certainly the most true to life portrait that has been done of him.” In any case, it’s the most disturbing. Gros only reveals a part of the secret. He gives us some indications of the Emperor’s sadness, but in veiled terms. The mystery of Saturn on horseback. Napoleon extends his gloved hand over the battlefield, while in the distance fire consumes Eylau. The sky is dark, swirling clouds of smoke rise from the burnt-out plain. With artists, light is always the signature of a painting. In this picture everything is black. The snow looks like soot, the Emperor’s pale face is half hidden by a dark growth of a beard. The face seems burned from the inside.

The king who worked miracles is now incapable of producing one. His gesture is dull, tired, and above all quite senseless. The victor, who looks like a ghost, doesn’t know what to do.... The most extraordinary thing is that he refuses to look at the battlefield; his moist, almost fearful eyes are gazing at the sky. (...)

Twenty-seven painters had taken part in a competition on this subject set by Napoleon and commissioned by Vivant Denon, the director of the Imperial Museums. Encouraged to enter by Denon, Gros was the last to apply. It’s interesting, this obsession of the monarch’s with wanting to immortalize the first great slaughter of his reign. (...)

Napoleon had ardently desired the art competition. He wanted to create the image of the conqueror full of pity. Of the illustrations required, the most essential one was mercy: the Emperor had to be shown in a compassionate attitude. It was not enough to reproduce the carnage; the artist had to go beyond the vision of horror through commiseration, comfort, indulgence. The victor sends help to the vanquished. (...)

Gros has included many details, like the bayonet dripping with bloody frost crystals. The painter asked Murat to make a sketch on the back of the preparatory drawing. He even went as far as asking Empress Josephine the favour of examining the hat and fur-trimmed coat Napoleon had worn during the battle. “He may keep them as long as he likes,” the Emperor replied. Gros kept them until the day he died. (...)

Everything is a portent in The Eylau Cemetery: resignation in the face of the fatal hour, hostile nature, the glaciation of memory, not to mention the comic note that inevitably accompanies the horror. In the center of the massacre is Murat, got up like an oriental prince, his leg showing to advantage, astride a bay horse bedecked with jewels. It’s an astounding, over-the-top image. Gros is apparently respecting the conventions of hagiography. The subjects’ gestures and the general impression of the battle conform to ideological necessities. Yet every detail works against the official propaganda. Gros tries to lessen the cruelty of the carnage by accentuating Murat’s self-conceit.

He was no doubt unaware of the caricature. Once he had finished the work, the artist had dreadful misgivings: had he given too much importance to Murat to the detriment of the Emperor? Gros was a very vulnerable man. In despair over the failure of his Hercules and Diomedes, he committed suicide in 1835.

Of course Napoleon, the sagacious leader of men, had understood it all.... What extraordinary expectancy, what uncertainty at that moment when Gros presents his painting and when the monarch sees his double with the mad, staring eyes for the first time? What will the icon say? (...)

He takes his own decoration of the Legion of Honour from his jacket and pins it on the painter’s chest.

#Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#Joachim Murat#Eylau#art#paintings#Antoine-Jean Gros#history#19th century#Napoleonic wars

113 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Holy Family on the Flight into Egypt, Dominique Vivant Denon, 1809, Cleveland Museum of Art: Prints

Lithography was discovered in 1798 in Germany by Alois Senefelder (1771-1834), whose efforts to find an inexpensive method to reproduce the text of his plays accidentally led to a new and revolutionary way of printing. Although lithographs were almost immediately produced in Germany and England, the artists of France were the first to appreciate the aesthetic potentialities of this most flexible, responsive, and personal medium. In 1806, one of Napoleon's generals, Baron Lejeune, an amateur painter, was impressed by the technique while in Munich. Upon his return to Paris, he succeeded in introducing a few artists to the method, and by 1811 Denon's studio had become a fashionable center of lithography for amateurs.

Size: Sheet: 23.7 x 19.2 cm (9 5/16 x 7 9/16 in.); Image: 9.7 x 14.1 cm (3 13/16 x 5 9/16 in.)

Medium: lithograph

https://clevelandart.org/art/1940.1097

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Profile Study of a Woman, Dominique Vivant Denon, 18th-19th century, Harvard Art Museums: Drawings

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Paul J. Sachs 70th Birthday Anniversery Fund

Size: 13 x 9.6 cm (5 1/8 x 3 3/4 in.)

Medium: Graphite on cream antique laid paper

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/296803

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shortly before Napoleon decided to invade Egypt in 1798, he met Baron Dominique Vivant-Denon at a party. Denon was a charmer, a favorite of Madame de Pompadour. He had held diplomatic posts in Russia at the Court of Catherine the Great, in Switzerland, and at Naples. Napoleon and Denon became close friends, and Denon, though in his fifties, went on the Egyptian campaign. His scholarship helped Napoleon choose superb museum objects, including the Rosetta stone that was afterward captured on its way to France by Lord Nelson and sent to the British Museum. Denon also aroused general admiration by his reckless coolness under fire. In 1800 Napoleon visited the Louvre for the first time and soon insisted that Denon be placed in charge of the museums of France and of all artistic services. In 1803 the Louvre became the Musee Napoleon, a name it retained until the emperor's downfall.

Napoleon and Denon, between them, devised a comprehensive museum system for France and her conquered satellites. Denon always sought the greatest masterpieces for the Louvre, but Napoleon made the final decisions, based on political expediency. As early as 1800, he had agreed to place paintings in the provincial cities of France that then included Brussels, Mainz, and Geneva. Eventually twenty-two cities benefited from the distribution of 1,508 paintings. Several museums were planned for Italian cities, though only the Brera Gallery in Milan, opened in 1809, was successfully organized; it received confiscations from throughout northern Italy.

Sometimes, reaction against French looting led to the establishment of museums. Thus, Louis Napoleon, king of Holland, founded the Koninklijk Museum (forerunner of the present Rijksmuseum) at Amsterdam in 1808. In Madrid, Joseph Bonaparte, king of Spain, worked with the artist Goya to keep the finest Spanish paintings from the clutches of Napoleon and Denon; later, in 1819, the collection was installed in the Prado and opened to the public. In 1813 Wellington captured paintings from the royal collection taken by Joseph on his flight from Spain. The duke offered to return them, but the Spanish government gave the 165 paintings to him. Today they repose in London as the Wellington Museum at Apsley House.

But those who live by the sword and the requisition shall perish by the sword and the requisition. When Napoleon was finally defeated at Waterloo in 1815, the paintings and art objects he had seized began to flow back to their previous owners. Not all of them returned; Denon's conveniently poor memory of their location saved a few for the Louvre, and most of those taken from churches and monasteries remained in France. But in all, the French museums gave up 2,065 pictures and 130 sculptures, including, of course, the Bronze Horses, Apollo Belvedere, and Laocoon. With tears of frustration in their eyes, the French people saw many treasures leave the acknowledged art capital of the world. Never again would so many masterpieces of painting and sculpture be on view in a single institution. Napoleon indeed had made great art and the museum symbols of national glory.

— Edward P. Alexander and Mary Alexander, Museums in Motion: An Introduction to the History and Functions of Museums

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Burgundian Arming Sword – late XVth century

Hand-forged spring steel blade, historically-dyed silk thread over velvet over hemp cord and wood core grip, hand-forged steel cross and pommel plated with 24 k gold.

And I think this one deserves a bit of an explanation…

Here’s a excerpt of the text I sent as a presentation for my lecture of November 2015 at the Klingesmuseum Solingen for the exhibition « Das Schwert – Gestalt und Gedanke » :

“Swords presenting a ricasso narrower than the blade are known – if somewhat rare – in the European Late Middle Ages and Early Renaissance. Literature however seems to be lacking concerning the subject – Oakeshott only acknowledging them as part of his XVIIIe sub-type, however with a long grip, and attributing them to the North of Europe (with other dubious example of possible Italian origin, one being in the Burrell Collection in Glasgow). Iconography regarding these types is also quite scarce.”

As a matter of fact, the only artwork I know of depicting such a sword is on the back panel of the Martyrdom of Saint Lucy (by an unnamed Flemish master known as the Master of the Figdor deposition) now kept in the Rijkmuseum in Amsterdam.

But over the course of my PhD I had the chance to document up close a sword with such a distinctive feature, that could not be related to any of the sub-types mentioned above. Kept in the Musée Vivant Denon in Châlon-sur-Saône, we unfortunately lack any information regarding the provenance of the CA 817 sword ; also, a non-neglectible part of the blade has corroded away.

And while I was helping preparing a temporary display of artifacts at the Musée Archéologique de Dijon to celebrate the publishing of the book “1513, l’année terrible”, the curator told me about another sword they kept in the storage rooms that had similar features – mainly a long, long ricasso (of course, far too late for me to include in in my dissertation)…but this time, the sword Arb.1437 had a provenance : it was found in the grave of Hélion II of Grandson (died 1505), Lord of La Marche, in 1853, the son of Hélion of Grandson, Seneschal to the Dukes of Burgundy. Weapon deposits in graves are a rare thing in late Mediaeval France, but another example in Burgundy is known.

All the while a third sword existed – and still exists, kept in the museum in Karlsruhe – displaying a similar, elongated ricasso (inv. n° G 60).

But all three swords have more in common than this peculiar, specific feature. The ricasso of the Karlsruhe sword bears the words “ME FIE / EN DIEU” in gold on a gold background (while the caption in the museum attributes this sword to Duke Philip III of Burgundy, this motto was not one of his however). Close examination of the remains of the La Marche sword revealed gold chips still adhering to the surface of the pommel and cross. And the Châlon sword not only bears three circular, undecipherable marks on its ricasso, the massive, cylindrical pommel still shows a silver inlay in its middle, and traces of silver-plated surface.

Futhermore, it appears that the Karlsruhe sword bears a maker's mark of a Maltese cross over three dots (barely visible on the pics I got of the sword, unfortunately). Or this very same mark appears on knife A881 of the Wallace Collection, but also on a pair of knives at the Rüstkammer in Vienna (D 260).......and on the pollaxe kept in Mâcon (223) that I documented in my PhD !

The Karlsruhe sword itself was possibly a present from Philip the Good to the Margrave Karl I of Trier, who later gave it to his brother, the Archbishop Johann II von Baden.

There *was* definitely a pattern here : swords, linked to noblemen associated with the Court of the Dukes of Burgundy (either before 1477 or after the exile to Austria), with massive pommels and long ricassos – and precious metal.

This sword is a mix of all of them.

Its proportions are based on what I could deduce from comparing all three swords, though it is rather on the upper side of things : the Châlon sword is 1054 mm long (albeit with a longer ricasso) – and still a hefty 1100g in spite of the heavily corroded blade. The cross and pommel are inspired by the La Marche sword : flaring quillons (also a common feature of all three swords) and a small écusson, and a large cylinder with concave front and back. And gold. I elected to use electroplating as fire gilding is strictly regulated in this country (for very good reasons).

The grip was strongly inspired by a surviving example of the fabric-and-thread covered grips of the late XVth century also visible in paintings of the time : the D9 sword of the Viennese Armouries, itself strongly associated with the successors of the Court of Burgundy as it was a hunting sword made for Philip the Fair; the fun part was to faithfully reconstruct and tie all the knots in silk thread. The grip is quite short, but the hand sits quite tightly between the pommel and cross – and allows for a nice fingering of the latter.

I also chose to give the blade a finish inspired by the Karlsruhe sword, wich also occurs on a lot of surviving blade surfaces : abrasive marks running crosswise to the length of the blade.

This sword, in spite of its fancy appearance and the precious materials used, is definitely not just a fashion accessory : it is meant for serious use, as, I believe, were all the original three swords that served as inspiration.

Velvet kindly provided by Wyte Phantom, silk thread by L’Atelier de Micky.

Dimensions :

OAL 1030 mm for a 887 mm blade (and 90 mm ricasso), 45 mm at its widest. Point of Balance is 2 cm down the blade from the ricasso. Weight is 1641 g

COGNOT Fabrice : L'armement médiéval : les armes blanches dans les collections bourguignonnes. Xe - XVe siècles, PhD dissertation under the supervision of Professor Paul Benoit, 711 pages, 2013.

OAKESHOTT Robert Ewart : Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge : Boydell Press, 1991, 320 pages.

OAKESHOTT Robert Ewart : The sword in the Age of Chivalry (revised edition), Woodbridge : Boydell Press, 1994, 204 pages.

Apologies for the mistypes.

80 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Louis Charles Auguste Couder - Napoléon visitant l'escalier du Louvre sous la conduite des architectes Percier et Fontaine, Paris, Musée du Louvre, 1833

Escalier neuf du Musée Napoléon construit par Percier et Fontaine de 1809 à 1812 (détruit par la construction de l'escalier Daru, dit de la Samothrace).

#Louis Charles Auguste Couder#Couder#Napoléon#Louvre#Musée#museum#musée du Louvre#Paris#Cordier#Fontaine#Daru#Denon#Vivant-Denon#vivant denon#Dominique Vivant Denon#painting#peinto#peintures#peinture#paintings#museum studies#muséologie#art#history#stair#stairs#museum stairs#museum stair#escaliers du louvre#escalier

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Boar Attacked by Dogs, Dominique Vivant Denon, 1789, Harvard Art Museums: Prints

Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gray Collection of Engravings Fund

Size: Image: 30.1 × 40.6 cm (11 7/8 × 16 in.) Sheet: 33.1 × 44.1 cm (13 1/16 × 17 3/8 in.)

https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/275555

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Landscape with Storm by baron Dominique Vivant Denon, Drawings and Prints

Medium: Etching

Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1931 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/385399

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leonardo : The Benois Madonna

In my Study, Leonardo: a Radical Suggestion, I cast doubt on the attribution to him of four major works regularly included in the canon of his painted oeuvre. In this Shorter Notice I want to cast doubt on another painting nearly always considered to be authentic Leonardo: the Benois Madonna in the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg.

The Benois Madonna (Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg)

This picture has a deceptively Leonardesque feel to it, but I began to be undeceived when I came across an engraving of the composition in reverse. A reproduction of this engraving lies among the Leonardo files at the Witt Library at Somerset House, the invaluable archive that no British connoisseur can easily do without.

Engraving by Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse from the collection of Baron Vivant Denon. Possibly 1829

The engraving, by a Frenchman, Mauzaisse, is subscribed as after a painting by Boltraffio, an attribution we can ignore. What is interesting here is the head of the Madonna: it is subtly different from that of the painted head of her as it now is, but strikingly similar to that of a drawing given to Verrocchio, in the British Museum Print Room.

Left to Right: The Benois Madonna; Engraving by Mauzaisse, Head of a Woman with Braided Hair by Verrocchio (British Museum)

That drawn head, clearly not by Leonardo, is most closely related to the head of the Virgin Enthroned, in the grandly spacious altarpiece sometimes called the ‘Madonna di Piazza’ in the cathedral at Pistoia, and to the head of the Virgin in a Verrocchio painting at the National Gallery in London, the Virgin and Child with Two Angels. Note the cupid-bow lips and weak eyebrows that everywhere characterise Verrocchio’s women.

Top Left: "Madonna di Piazza' (Pistoia) Top Right: Virgin and Child with Two Angels (National Gallery London) both Verrocchio. Details of the lips and eyes characteristic of Verrocchio

Turning from the head of the Virgin in the Benois Madonna to the naked Christchild, we find the above connections reinforced by a drawing, very much in Verrocchio’s style, from a Polish collection

Drawing of the Christchild from a Polish Collection (Can someone tell me where?)

This Child is not exactly in the pose of the Benois Child, but He is very similar in bodily type.

Detail of the sleeve from the Benois Madonna and a drawing by Leonardo - study of drapery for the arm of St Peter (Royal Collection Windsor)

It is agreed that the Benois Madonna has been much tampered with in the past, and one of the alterations is suggested by the brushwork on the sleeve and further down in the folds of the brown lining of the blue mantle. This is distinctly like Leonardo’s highlighting of folds, as in this drawing from Windsor. The present colour scheme of the Benois Madonna is puzzling, not particularly reflecting the palette of either Verrocchio or Leonardo. As for the window with the featureless sky, it seems surprising that Leonardo would resist the temptation to include some distant mountains, even if that meant having the window lower down.

The Benois Madonna will probably remain a bone of contention among scholars, but my hunch, as a connoisseur, is that Verrocchio painted it originally, but that Leonardo, here and there, added touches of his own. What others have done to it in the centuries following is for conservators to work out. There is much else regarding Verrocchio for connoisseurship to clarify; the Benois painting is only an outlying problem within his oeuvre. What it illustrates, from an aesthetic point of view is the often unsatisfactory nature of a hybrid work involving more than one artist, even when those are of the calibre of Verrocchio and Leonardo.

0 notes