#alan pakula

Text

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harper Lee with producer Alan Pakula and with actor Mary Badham on set of Robert Mulligan’s TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD (1962)

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alan Pakula - The Parallax Wiew - El último testigo

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Parallax View and The Conversation: A Conspiracy of Looking

What is the point of a conspiracy theory?

Usually we see them defined as a way of outlining how plots against unsuspecting victims. It creates a narrative for “us vs. them,” a way to make sense of an often chaotic world. I had an entire podcast dedicated to it, talking about everything from the 9/11 attacks to MK Ultra, and even Bigfoot and other cryptids. But they always revolve around the same thing: the world is messy, there’s a plot against us, and these are the reasons why. We are storytelling creatures, and the story helps explain things in more comforting ways than “we live on a rock careening through space and are at the absolute whims of nature.”

Films around conspiracy theories are great ways of dealing with the messiness of these issues because they can easily cast compelling actors into convoluted plots that can delineate lines between good and evil. From movies like The Manchurian Candidate (1962 and remade in 2004, respectively) and Seven Days in May (1964), we begin to see how shadowy figures can be responsible for massive changes in the world. It’s easy to believe that those corporations and politicians we entrust with our goods and government would be sinister and want to enslave us; the reality of the world is much harder in that there are multiple systems and machinations set in place that take so long to grind to stop that we may never get to really change them. It’s easier to change ourselves than the system...that is, if we’re willing to change.

The Parallax View and The Conversation are two films released within three months of each other in 1974. They both were crafted by excellent filmmakers (Alan J. Pakula and Francis Ford Coppola) with a focus on looking at how conspiracies and plots are set up. The difference is where the locus of control is placed. The Parallax View is focused on the unseen “them” of conspiracies, where we learn how the Parallax Corporation acts as an intermediary for political and social control. The Conversation is all about “us,” where we are under surveillance and act and react to the fact of being recorded.

The Parallax View focuses on the shadowy corporations and assassinations that became responsible for being the middlemen in plots against figures who are murdered suspiciously. Warren Beatty is there as a womanizing journalist named Joe Frady who witnessed a political assassination in Seattle at the Space Needle, and stumbles onto a pattern of murders committed against the other witnesses. Obviously riffing on the JFK assassination and the Warren Commission’s findings, Pakula plays with perception and fear in his examination of paranoia and how it manifests. The sense of discovery is largely what makes the movie so successful, as Frady soon sees that the Parallax Corporation is consistently growing and employing sociopaths and those who associate negative emotions with positive accomplishments.

This last part creates the best element of the movie, and it is breathtaking in its representation. Almost as though Frady jumps into the internet forty years after its release, The Parallax View makes its viewer experience the personality test in its horrific totality. It’s possible to watch this and see exactly what is so appealing about Parallax as a way of giving power to people that fall outside of the mainstream of society, which is eerily reflective of the rise of conspiracy theories like QAnon and its ilk in the modern era.

Frady is recruited by the organization and ultimately tracks down the plans of the Parallax Corporation, which is targeting another Senator with policies that go against their interests. Cleverly outsmarting a planned detonation of a plane, Frady then tracks down the senator to a rally, where the politician is gunned down. Suddenly he’s fingered as the culprit, and as he tries to make his escape, Frady is shot by the recruiter that brought him into the organization. Pakula ends the movie with a simple interior shot of an almost faceless committee reading the Parallax Corporation’s intended narrative about Frady, which was his isolation as the patsy assassin. Fade to black, it will happen again, and Gordon Willis’s famed dark interiors match our moods as the credits roll. The unhappy ending is part of the appeal of The Parallax View, as it released during the Watergate hearings and denouement with President Nixon’s resignation before facing impeachment. It’s a dark mirror of our country at a time when public trust in institutions was badly damaged. Little would change over the next half century.

The Conversation is a strong internal companion to the sprawl of The Parallax View, looking at the interiority of protagonist Harry Caul’s life and finding it wanting. Caul’s life is spent in surveillance – of others and of himself. He constantly monitors his own actions and those of others to keep people at arm’s length, seeking to be the best wiretapper in the country and thus trusting nobody. Unwilling to let others in, and he can’t open up, Caul exists in a bubble of his own making. He breaks up with the girlfriend he’s afraid of admitting he has; he doesn’t answer questions about his personal life; he’s clearly repressed, and when we learn that his last east coast job resulted in the murder of an entire family, we can empathize to an extent.

It's fitting that I saw this so soon after revisiting Klute as it also has a similar focus on technology and audio. Caul thinks that he’s uncovered a conspiracy on a job trailing two errant lovers, and he fixates on the details of the tape, which unleashes its static hiss and obscures as much as it reveals. Coppola lovingly focuses on the different mechanisms that are used to reveal the conversations, with Caul only coming alive as he reveals the audio and uncovers what is a plot about the possible murder of the people he’s surveilling. Coppola also twists the knife by never revealing much about the plot, leaving his audience to learn the possible meaning with Caul.

youtube

The party that happens midway through the film is a fulcrum point for the audience and for Caul. We see him in his element around other conspirators, people that are experts at wiretapping but wholly oblivious to the human experience. They don’t seem to care about the possible destruction their constant surveillance will do to their subjects, and includes Caul in their list of subjects when a pen microphone reveals some truths about the protagonist of the movie. How scared he is to talk to women; how much the murders weigh on his mind; and how much he pushes away anybody that dares to look underneath the surface. The sex worker he sleeps with that night steals his recordings away, as the client who asked for them was getting impatient.

The final reveal is ultimately satisfying because of how much it plays with audience expectations. Caul believes he’s stumbled onto a plot to kill the two wayward lovers, and he heads to the hotel they stated they would frequent, only to find the girl already dead. Or is she? In a stunning twist, the wife of the executive that paid for Caul’s tapes turns up alive, with her husband murdered by her lover and his assistant. Brilliantly, they used Caul’s paranoid nature to create the conspiracy. It’s all about his personality, which is how they trap him. At the end of the film, as he searches for an impossible bug that is planted in his apartment, he tears apart his world, leaving himself only to play along with a recording that he has destroyed. The pessimism that was in The Parallax View manifests again in the personal, which is the masterstroke of The Conversation.

youtube

Small wonder that both these movies resonate almost a half century later. The Parallax View and The Conversation show the pernicious effects of paranoia, of believing that somebody is always watching you, and of always watching and listening to others. Movies like these with major stars don’t exist anymore in the budget-conscious and fearful studio system, as superhero films pay homage to them without implementing the banalities that Pakula and Coppola sprinkled into their fantasies. It would be impossible to recreate the moment of The Parallax View, where a decade’s worth of paranoid fiction merged with the seismic news of the Sixties and Seventies, and we found ourselves at the other end of forces beyond our control.

But it is possible to imagine ourselves as Harry Caul, obsessed with technology and its implementation. It’s possible to see how our very natures could be turned against us. Companies like the Parallax Corporation (or Meta, in this case) do it all the time, gaming us against our own wills to produce simple Skinner box content. In the end, all these movies do is reinforce how we are also watching ourselves, making it impossible to look away even when the price is more than we can bear. The real conspiracy theory isn’t us against the invisible other. It’s us against ourselves...and we always lose.

#conspiracy#conspiracyfilm#parallax view#the conversation#francis ford coppola#alan pakula#gene hackman#warren beatty#film review

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

STREAMING SATURDAYS! Natalie Wood and Steve McQueen Fall in LOVE WITH THE PROPER STRANGER

STREAMING SATURDAYS! Natalie Wood and Steve McQueen Fall in LOVE WITH THE PROPER STRANGER

View On WordPress

#abortion#alan pakula#arnold schulman#classic film#classic movies#edie adams#elmer bernstein#herschel bernardi#love with the proper stranger#milton krasner#natalie wood#robert mulligan#steve mcqueen#tom bosley

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Which director's filmography would you rather listen to a series of podcasts about?

Consider also voting on the actual poll at Blank Check’s website

Current standings

#Blank Check#Blank Check with Griffin and David#Ridley Scott#Alan Pakula#film#director#Blade Runner#The Pelican Brief#all the president's men#Gladiator#thelma and louise#tumblr polls#Klute

0 notes

Photo

The Parallax View https://bit.ly/3SbNBIf One of three 1970s thrillers Alan Pakula directed in quick succession, The Parallax View is sandwiched between two better films, Klute (1971) and All the President’s Men (1976), the second leg of what’s now known as his “paranoia trilogy”. Posterity is in the process of polishing The Parallax View’s reputation, with the focus usually on two aspects: the cinematography of Gordon Willis and the conspiracy at the centre of it, which is not, for once, all a big government put-on. Instead it’s a big bad company, the Parallax Corporation, that’s pulling the strings by seeking out unstable individuals and then grooming them for political assassinations. Don’t tell Ayn Rand. Loren Singer’s original novel … Read more

0 notes

Text

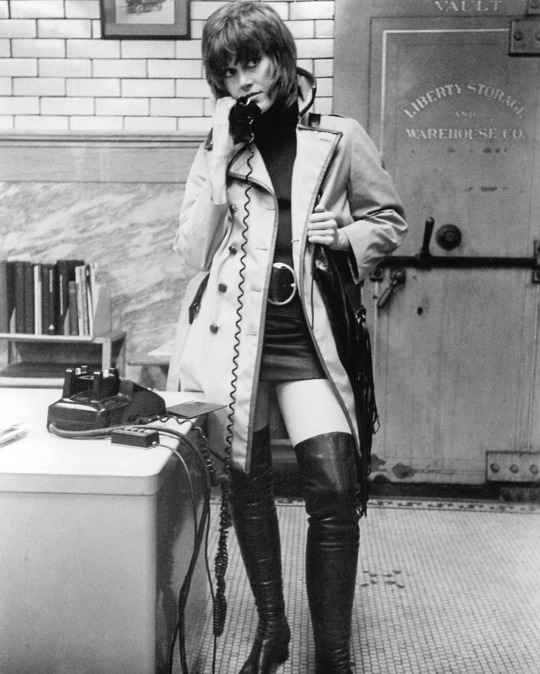

Jane Fonda on the set of Klute, 1971

536 notes

·

View notes

Text

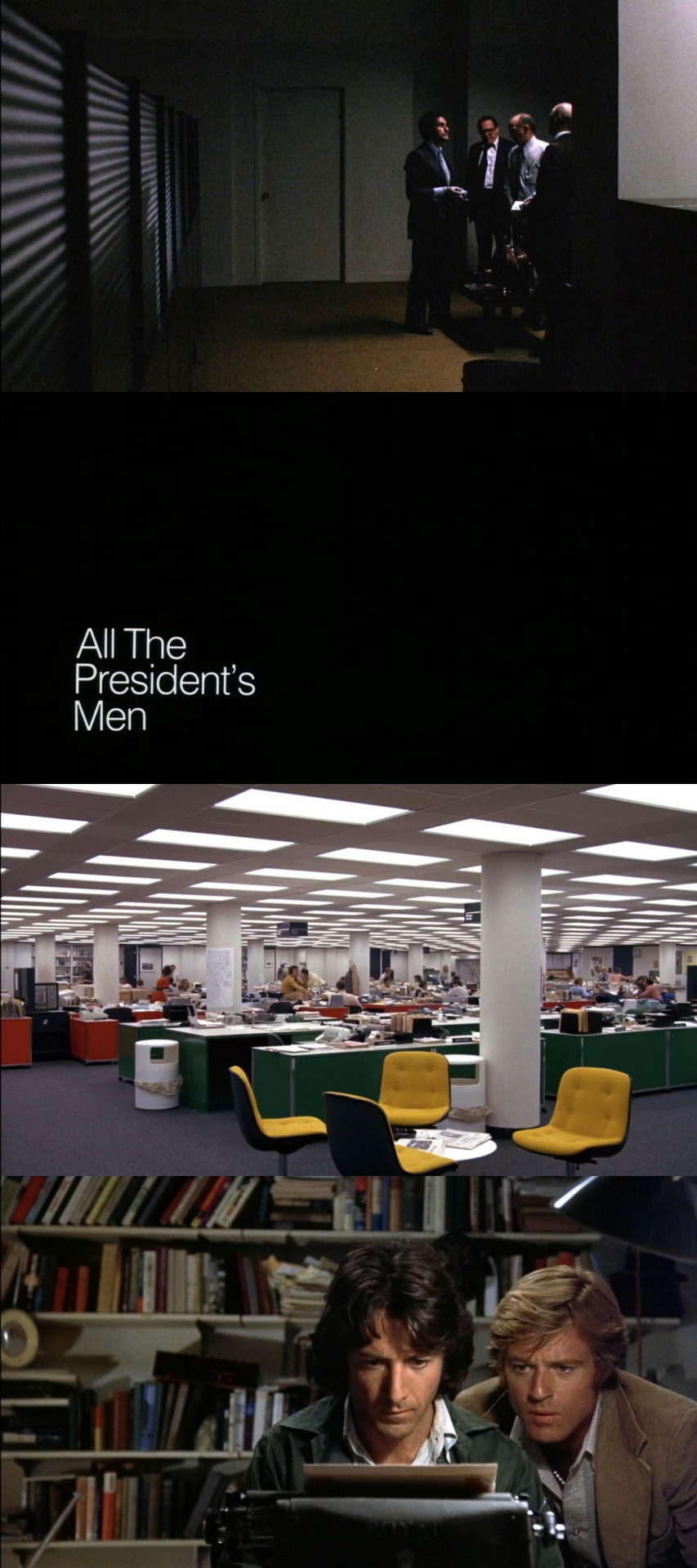

All the President's Men (Alan J. Pakula, 1976).

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meryl Streep in Sophie’s Choice, Alan J. Pakula, 1982.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Roy Scheider and Jane Fonda in Klute (1971)

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

All The President's Men (Alan J. Pakula, 1976)

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Klute and 50 Years of the Same

You should see the movie Klute. It’s a deeply engaging conspiracy drama made by the incomparably nimble filmmaker Alan J. Pakula. But the conspiracy isn’t the reason you should watch it. Rather, it’s the lessons we can take from the movie 50 years after its release while we are surrounded by misinformation and pure, sheer idiocy from the most powerful people on high.

This will require me to spoil the hell out of the movie. If you want to go in unscathed by information, just let me say it’s a masterful and ferocious movie, stunning in its insightfulness and cutting in its ferocity. There’s a reason it’s in the Criterion Collection, and the visuals and performances all connect to its importance.

Okay, good? Good. Let’s talk about Klute.

Klute is a movie about prostitution, how one woman contorts herself to fit within the world of men while also wrestling deeply with the ideas of control. It’s the story of Bree Daniels, a struggling actor in 1970s New York City who can’t get a break on the stage, but who transforms into a person that makes men’s fantasies come true when she needs to break away from the drudgery of her day.

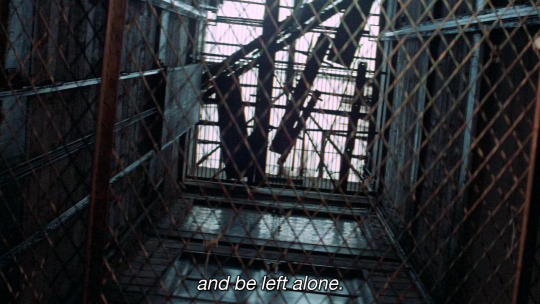

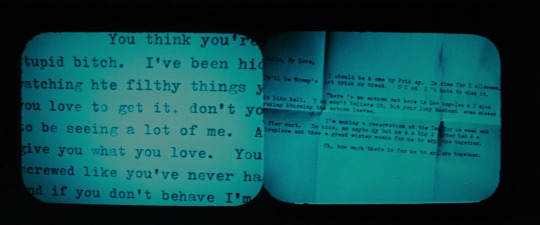

It’s also about a man that appears obsessed with her, who may be leaving her obscene letters and calling her at all hours of the night while breathing heavy. The investigator John Klute comes from Tuscarora, Pennsylvania to the Big Apple to find his friend and to ask Bree some questions, tape her phone calls with clients, and look at her life as a call girl. It’s a movie about watching, about listening, about simple cues that indicate a lack of control in the world around them. All of them grappling for answers, none of them thinking of the right questions. It’s maddening. It’s stunning. I couldn’t look away.

So you’ll probably figure out the mystery halfway through the film. I did, but not because it’s a bad one. Rather, it’s the simplicity of the story that really stayed with me after the film ended. It’s a movie about how little control of her life Bree really has, but how fiercely she holds onto herself. The movie doesn’t judge her for her life, and often shows her life as a sex worker as preferable to the banal dismissals that make up her normal existence. Indeed, it starts with an image of actresses in a cattle call. The film never says what they are gathered for, and all of the women experience the same level of dehumanizing behavior by the callous professionals. Some are told they are too pretty, some are told they are not pretty enough, and when Fonda’s Bree is shown in the frame, all they say are “hands!” She shows them. They’re not impressed and never say why. They move on, and nobody is happy. It’s a day in her life, but it tells us more than a lifetime of backstory would.

Fonda shines in the scenes when she’s calling on clients, taking them into her arms in their grubby New York City abodes. The hotels are sparse and shabby. She doesn’t mind, she walks in and manipulates her clients into opening up, saying what they really want. Bree’s actions are understandable, while the men in her clientele are all varying degrees of pathetic and repressed. The reciprocity of the life of being a prostitute are on display here, with her fulfillment of her johns’ fantasies also rewarding her with the control she can’t get in her daily life. Fonda’s eyes come alive as these scenes show her fully owning the men that love to love her.

A second scene shows a more tender form of control and fantasia, as an older garment factory owner brings her into his shop for an evening rendezvous. Fonda stuns as she walks through the factory, Michael Small’s score swelling up under her as she comes to seduce a man with a monologue about being seduced herself by an older European man. She takes her clothes off, but the whole time she is speaking she is stripping him to the bone, revealing in her words what he wants and can’t bring himself to say. Fonda’s magnetism in this scene stunned me, her eyes dancing around the scene as famed cinematographer Gordon Willis bathes her in darkness at the edges of the frame. Bree dances through the scene as though she is finally freed, and we all see and understand why somebody who is ignored in her real life would give herself to this one.

This doesn’t stop Donald Sutherland’s Klute from observing her, a decent man who inevitably falls into her spell. Klute is staid and by the book, his power coming from his station in life, but he never seems to enjoy himself until Bree confronts him about being questioned and taped. Their connections form a more interesting drama than anything that emerges from the conspiracy angle. They grapple with each other, Klute and Bree showing themselves at their worst and their best. As they work together to solve the case and track down the missing prostitutes that have possibly been murdered by the stalker tracking down Bree, they come across a fellow call girl hooked on heroin. They silently watch as the mirror of 1970s New York points out the lowest possible point, each of them seeing another possible version of themselves. All it takes is a slip, a fall into total control. No wonder Bree fights for her own life at every turn, making sure that every step along the way is hers and hers alone. No wonder Klute sees himself coming alive as she threatens his idyllic life, witnessed only once in the beginning of the film.

Mark Harris wrote about the movie in his essay for the film’s entry into the Criterion Collection. In it, he accurately points out how the film’s genre belies the character study it provides.

It could have gone wrong so easily. But the movie that resulted from this nervous collaboration embodies, in the most rewarding way, the transformations and contradictions that defined American cinema at the dawn of one of its most creatively fertile eras. Klute is not, as Pakula feared it would be, “a character study in a melodrama” but rather a character study that uses the trappings of melodrama to deepen its portrait of the character it’s studying. The film undercuts every expectation it sets up: it’s a cop movie that isn’t about the cop; a modern western that almost never leaves the canyons, hideaways, and saloons of Manhattan; a whodunit that, with defiant indifference, gives away the “who” after forty minutes; and a thriller that, although menace seems to choke every frame, contains almost no violence at all. No wonder some critics were baffled: Variety’s reviewer dismissed it as a “mixed-up sex-crime pic” and a “suspenser without much suspense.” The Village Voice’s Molly Haskell, one of the first to grasp what Pakulawas doing, put it better, writing that he “uses suspense the way some people use music, as background atmosphere.” (In that, Pakula got an essential assist from Michael Small’s eerily evocative score, which always seems to suggest unsettling sounds coming from the next apartment.)

So it should come as no surprise that the conspiracy angle of Pakula’s movie is actually its weakest point. The banality of the reasoning behind Bree’s stalking matters far less than how it impacts her. Pakula’s focus on recording technologies is fascinating, honing in on surveillance devices that capture us in bits and pieces, something he’d bring to full effect in The Parallax View (1974) and All the President’s Men (1976). Contemporaries like Francis Ford Coppola (The Conversation) and Brian De Palma (Blow Out) obviously used Klute’s fascination with tape recorders and suffocating images of men in glass towers to highlight how panoptic logic and its power suppresses both those in charge and out of it. Unlike most of these movies, Klute ends on a hopeful note. Not one with an immediately happy ending, but at least Bree is still in control of her own destiny.

youtube

It’s this control that is so different from other films, particularly those that we see in our modern surveillance state that we ostensibly “control” by social networking algorithms and platforms that determine our information flows. We have more tools than ever to control our digital images and offerings, but we remain under the spell of others that break our data up into small categorized and keywords. We’re all bits of ourselves that stress under the innocuous banality of invisible men with simple desires that we can’t control or understand, much like Bree’s all but unseen nemesis who is a slave to his drives, no matter what the social cost. All that matters to him is his next victim, a glass tower above the world separating him from the prey he can’t hope to understand. All that matters to her is the drive to keep moving, to keep living a life of her own. Bree’s vitality is juxtaposed against his blasé nature. No wonder Klute is like us, enraptured by her presence. Pakula and Willis frame Bree in the center of almost every scene she takes, her light keeping the darkness away from her by almost sheer willpower alone. That hope is harder to come by in an age where we think we control ourselves, but remain away from the custodians of information that drive us to our next short term dopamine fix.

A city on a downward spiral. An investigator that falls for his subject. A bland murderer that can’t escape his lonely, sad nature. And throughout all of Klute, there’s Bree, a woman that won’t be pigeonholed, who won’t give up the control of her own life for others. She may not stay with our hero by the end of the movie, but we still enjoy a happy ending because at the end of the day, she still has her agency. Given how much we seem to have given up 50 years later, it’s a conclusion worth celebrating, which makes Klute a masterpiece that may truly have found its place even after half a century.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

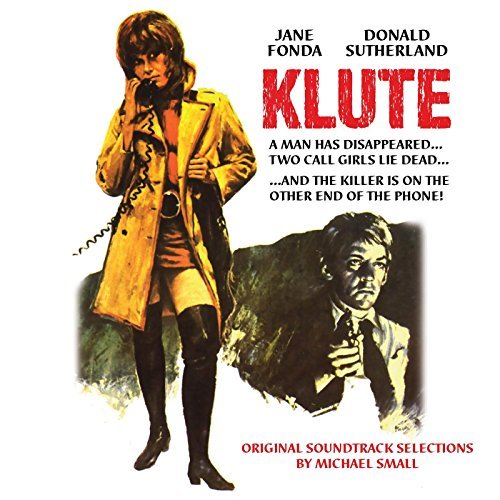

KLUTE (1971) dir. Alan J. Pakula

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Meryl Streep on the set of “Sophie’s Choice”

directed by Alan J. Pakula, 1982

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Klute (1971) dir. Alan J. Pakula

23 notes

·

View notes