#alice gribbin

Text

Alice Gribbin on the prejudices of the institutional left above, Matthew Gasda on the prejudices of the anti-institutional right below. You shall know them by their theories of art. If they think art flows directly out of political power, then they think the inmost recesses of humanity can and should be rationalized and operated by the same power. "Left" and "right," in this case at least, are entirely irrelevant. The sociology of art is inherently a totalitarian prospect.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

God of a lack of abundance,

ablative god, in the middle of a procession, in the middle of things god,

your desires are showing.

Jade dust in the hair of those who quarry rough slabs of jade

is not the definition of plenty.

What then is too much, when a sleight of the rational names plenty

as recursion in thickets, absent blaring data

and the insects vanish.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art should not be expected to make one feel better, in some therapeutic sense, or make one a better person, in a moral sense. Art should make one feel more human, more alive to one’s own spontaneity, contradictions, and irrationality.

Alice Gribbin, The Empathy Racket

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Bartłomiej Pękiel - Audite mortales · ·

The Sixteen : Eamonn Dougan · Charlotte Mobbs · Alice Gribbin · Jeremy Budd · Nicholas Mulroy · Matthew Long · Stuart Young

0 notes

Link

Artworks are not to be experienced but to be understood: From all directions, across the visual art world’s many arenas, the relationship between art and the viewer has come to be framed in this way. An artwork communicates a message, and comprehending that message is the work of its audience. Paintings are their images; physically encountering an original is nice, yes, but it’s not as if any essence resides there. Even a verbal description of a painting provides enough information for its message to be clear.

This vulgar and impoverishing approach to art denigrates the human mind, spirit, and senses. From where did the approach originate, and how did it come to such prominence? Historians a century from now will know better than we do. What can be stated with some certainty is the debasement is nearly complete: The institutions tasked with the promotion and preservation of art have determined that the artwork is a message-delivery system. More important than tracing the origins of this soul-denying formula is to refuse it—to insist on experiences that elevate aesthetics and thereby affirm both life and art.

In the popular imagination, the great corrupter of the visual arts is the art market, with its headline-making, eight-figure auction house sales of works by living artists. The secondary art market is indeed obscene, but to blame the market for all that’s wrong with contemporary art is to disregard the no less pernicious motives of the apparatus of messaging that is foisted upon artworks by nonmarket institutions and their attendant bureaucracies. Private and public museums and galleries; colleges and universities; the art media; nonprofit, for-profit, and state-run agencies and foundations: These institutions adjudicate which living artists are backed financially, awarded commissions, profiled, taught in classrooms, decorated with prizes, publicized, and exhibited.

Institutional bureaucrats, not billionaires, have the power to constrain the possibilities for aesthetic development in the present. The figure of the contemporary artist we know today is an invention of the bureaucrats. He, like them, is a managerial type: polished, efficient, a very moderate, top-shelf drinker. His CV is always up to date. He worries about climate change. The likelihood he graduated from an Ivy League university is especially high; he may himself be a tenured professor (a near given for literary artists).

The nonmarket institutions of the art world, all vanguards of the progressive movement, have telegraphed that such a profile is compulsory for artists. They should be camera-ready and, if nonwhite, eager to discuss matters of identity. Like shrapnel, the words “justice,” “legacies,” “confront,” and “decenter” ideally will litter any personal statements on their work. To conform to these expectations is to be savvy, a prerequisite for success. Such is the figure of the institutionally backed artist.

How any one individual chooses to pursue his career is not of particular interest to me. There will always be artists who are, and those who are not, corruptible, whether their patrons are the Medici, the CIA, or the Mellon Foundation. Bad art, wonderfully, is in the end forgotten. As tiresome, didactic, and predictable as much contemporary art may be, I venture that a different corruption by the institutional bureaucrats should trouble art lovers more. While the market has turned artworks into mere commodities, the vast machinery of the art world has turned artworks into artifacts, by zealously, and almost exclusively, upholding the artwork as an entity with a message to convey.

…

We derive meaning from artworks privately. The experience is interior and unfolding, often difficult to describe to others. Meanings can strike us, entering our psyches in a moment, involuntarily, driven by some hidden force. More commonly, meaning opens up within us slowly: on the third, closer read of the poem; after evaluating a painting for some time, once the eye has roamed and settled and roamed again, noticed detail, related parts to their whole. After an initial sensual impression, our faculties that make meaning are gradually enlivened—emotional, psychological, spiritual, intellectual.

…

Late in the 20th century, it was decided within the art world that the freedom of individuals to extract meaning from artworks in manifold ways had become excessive. So pervasive was the watery idea that art means whatever you want it to mean, that all opinions on art are equally valid, the public needed reigning in. This concern is reasonable. Of course, not anything that can be said about an artwork is worthwhile, and to be discerning about art is necessarily to be discerning about art criticism. But encouraging greater discernment has not been the mandate that arts institutions have chosen to pursue.

Instead, over the last 20 years the museums and galleries, universities, media, agencies, and foundations moved to shore themselves up as the rightful experts on art by asserting that an artwork is not a site of numerous meanings but that which contains a single blunt message. One receives such a message publicly, not in private. It is delivered with the expectation of being acquired whole, and of being understood quite as the artist intended. This is utilitarian art: Its value lies not in itself but in its moral or political content. The majority of artists supported and promoted by the private foundations and government agencies, universities, and galleries today produce work of this kind.

Meanwhile, in the museums, artworks made any time before the mid-20th century are being framed as containing their own messages, which generally underline the superiority of present-day beliefs and practices at the expense of aesthetics. This turn in the framing of visual art has been experienced by many as a relief. Those within institutions feel they are legitimate again, with the power to restrict, by various means, what had become too open. Conversely, much of the educated public feels newly empowered, because they get to feel they understand the art. Visiting a museum now is like watching cable news—undemanding yet edifying, thanks to the panel of experts who untangle and interpret for the rest of us.

What is so terrible about that? To approach an artwork primarily concerned with grasping its message is necessarily to bar oneself from aesthetic experience. Utilitarians decommission their all-too-human parts—their spiritual, sensory, and emotional faculties—each time they encounter art. Out of ignorance, they conflate the aesthetic with the cosmetic: shallow, a matter of appearances. They could not be more misguided.

…

In answer to the question of how this mass debasing of art has come about, I can offer one preliminary explanation. The prevailing institutional orientation to art has seeped from the academy, like bog water, up and out into the public-facing art world. In college humanities departments, the main type of work carried out is best described as diagnostic. Students are taught to produce information about culture—including artworks—using analytic methods first propounded in the fields of gender and ethnic studies, and, most of all, cultural studies. Beginning in the 1980s, and certainly over the last 20 years, cultural studies critiques have become the dominant mode of inquiry in the humanities.

Cultural studies analysis thinks of art not in itself but as a sort of rash brought on by culture, or a spore that a culture puts out. Art—just as billboards, contraceptive marketing, and horticulture periodicals—is considered a symptom or emissary of the society from which it emerged. Solely on the basis of what it demonstrates about its time and place is art a subject of study. Naturally, an artwork’s aesthetics are irrelevant in the cultural studies mode of critique; no one work of art is any better, or more significant, than another. In its predominant lower forms, cultural studies is a kind of supremely unrigorous social studies, practiced by people who believe all art is propaganda.

…

The number of new jobs for humanities professors started declining in the late 1970s; following the 2008 financial crisis, the job market collapsed. Rather than continue in academia on the tenure track, successive generations of humanities Ph.D.s instead have become K-12 teachers, editors, cultural critics, arts administrators, and nonprofit workers. Almost every employee in the cultural professions has a humanities bachelor’s degree, and many have postgraduate training. Obedient as nuns, all have been trained to regard aesthetic experience with suspicion and seek from art a diagnosis of society.

Two exhibitions installed at major museums this year perfectly illustrate the institutions’ debased approach to art.

…

Judging by their biographies, the experts broadly share a certain set of approaches when it comes to art. What kinds of “insights” do they offer about the paintings and prints on display?

When beholding A Midnight Modern Conversation, Hogarth’s bawdy engraving, “we are clearly meant to find the men’s woozy misbehaviour funny. However, we might also consider that the punch they drink and the tobacco they smoke are material links to a wider world of commerce, exploitation, and slavery.” Harder to laugh at the image now, is it not? A similar point is delivered more bluntly elsewhere: In the second painting from Hogarth’s satirical sequence Marriage A-la-Mode, “however indirectly ... the atrocities of Atlantic investments are invoked in relation to the outsized expenditures on Asian luxury goods.” The work is, “overall, a picture of White degeneracy.”

Audiences are encouraged to “look out for” characters in the margins. The labels to many multicharacter compositions focus exclusively on minor figures, who apparently are the key to understanding the works. The two texts accompanying Hogarth’s sardonic painting Taste in High Life, a sendup of the indulgence and pretensions of the upper classes, discuss solely its racial elements. About the young enslaved servant, “These children were dehumanised and treated like pets”; in the caricatured white shoppers, “it is as if Hogarth’s worst fears are being realised, with the figures corseted into the objects of their enslavement.” On John Greenwood’s Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam—depicting a large group of drunken men partying to excess—both commentators write exclusively about the enslaved figures: “The imagined Black presence in Surinam’s contemporaneous life is laid bare, alongside the free abandon of Whiteness as power.” The way an enslaved man is rendered holding a bowl “suggests that his body is no more than an inanimate thing, a mere means to a debauched end.”

In Hogarth’s painting Southwark Fair, a chaotic and exuberant crowd scene, the curators choose to bring our attention to the “racist juxtaposition” of the dog and the Black boy trumpeter, which “signal[s] deepening ideas of racial difference pervasive in eighteenth-century culture.” An irreverent painting by Dutch artist Cornelis Troost, in which a man flanked by trumpeters in blackface at an upstairs window moons a crowd below, is a meeting of “black-face and white-bottom ... or Racism and White supremacy, challenging the audience within and without the painting.” These comments barely pretend to educate viewers about the art. On the contrary, they instruct viewers on what to think.

Representation is all: Images rely on “antisemitic visual conventions,” or play into “stereotyped representations of people with dwarfism,” or associate “female sexuality and sex work with moral decline.” Hogarth takes “a conservative view of class mobility and change.”

…

In a self-portrait of the artist at work, the chair in which Hogarth sits “literally supports him and exemplifies his view on beauty. The chair is made from timbers shipped from the colonies, via routes which also shipped enslaved people. Could the chair also stand in for all those unnamed Black and Brown people enabling the society that supports his vigorous creativity?”

In posing her assertion as a question, the author of this label—herself an artist—feigns being diplomatic. Really, she is being slippery. Do you think her question has more than one correct answer?

…

Carpeaux—whether he knew it or not, despite his public support for emancipation—through his artwork gave expression to such racist “fantasies.” Abolitionist admirers of the sculpture in Carpeaux’s own time committed a similar sin: According to a wall text, “the replication and sale of Why Born Enslaved! in miniature echoes the commodification of people of African descent that took place under slavery.” The longstanding status of Carpeaux’s sculpture has been a fiction. Finally its true meaning is being revealed.

Throughout the exhibition, audiences are informed that “underlying” Carpeaux’s sculpture are “the hierarchies of race”; that it embodies “colonialist influences” and “belongs to the tradition of artworks that conflate Black personhood with depictions of captivity.” Various other 18th- and 19th-century artworks are showcased as examples of this tradition. Given the show’s explicit aim of recasting Why Born Enslaved!, the preponderance of wall texts and explanatory labels is unsurprising. Indeed, the exhibition texts are ultimately more important here than the artworks, which feel less like the show’s substance and more like evidence brought in to support the curators’ statements.

Given how they are framed, responding personally to these works is especially difficult. The curators are intent on foreclosing any alternate meanings the art might have for audiences. For me, Bartholdi’s bronze figure Allegory of Africa is an arresting piece of figural sculpture. It is too striking for me to depend on its title for meaning. Turning to the object’s label, then, how am I meant to square my aesthetic impression with the museum’s interpretation—that the artist’s “emphasis on the figure of Africa’s muscular body, facial features, and hair texture reflect the increasing prominence of ethnography, a pseudoscience that saw physical appearance as evidence of racial difference”? That sounds horrible! Perhaps I should defer to the Met.

Other descriptions may catch one off guard. On display is an attractive sculpture by Jean Antoine Houdon of the head of a Black woman, later repurposed by the artist with an inscription commemorating France’s first outlawing of slavery. By giving the woman pierced earlobes, Houdon, we are told, has “emphasized the exoticism of his subject.”

…

For a museum to tell audiences this is not a portrait—that the artist has not captured in the precise turn of his subject’s head, in the strain of her brow, the set of her jaw, her lips, and her unforgettably defiant eyes a singular human expression—is astonishing. No, the Met says. This figure is a “type.”

That word shows up frequently. About a bronze work Carpeaux sculpted after a living man, the label reads: “While the artist has carefully modeled the features of his sitter, the bust’s historic title, Le Chinois (The Chinese Man), transforms this likeness into an idealized ‘type,’ or stand-in for an entire people.” This bizarre statement assumes the title of an artwork overrides the experience of looking at it, implying a viewer’s aesthetic impression of the sculpture is so hollow and fleeting that, upon learning the work’s title, she will discover her eyes were lying. It’s an oddly insulting assertion for the museum to make. But Carpeaux’s sculpture, the curators insist, cannot be divorced from the barbarity of his time: “At the same moment that this dignified representation proliferated in elite European interiors, Chinese workers in the French West Indies labored under coercive contracts intended to facilitate the continued production of sugar after the abolition of slavery.” That is how the artwork should be understood.

For a wall text, a University of Chicago Law School professor provides a definition of abolition from the antebellum period, and ties this to the modern movement to abolish police and prisons. Addressing the question “What is representation?” a filmmaker and professor of French studies recalls a racist children’s television program from the 1970s, and likens false representation—extraordinarily—to “shackles or a rope around the neck.” Elsewhere, an artist offers the following insight: “Despite his best intentions, as a white male artist Carpeaux is only able to convey his perception of a world about which he has only an idea ... If we don’t [contextualize his imagery], the bust allows us to accept that the Black female body can still be collected and consumed, be gazed at, desired, despised, dissected, and distorted by all.” The presumptions behind this grand rhetoric are baffling, but the exhibition’s stakes could not be more explicit: There is a right way and a wrong way to think about this work of art.

…

For herself, if she wishes to have aesthetic experiences, the individual art lover must come to recognize and reject the institutions’ utilitarian framing of art. The diagnostic approach of experts is baked in to new exhibitions, as it is in humanities departments, the arts media, and philanthropic foundations. Categorically ignoring any but the most basic museum labels is the first thing an art lover can do.

Beyond that, she is on her own. But she always was. The great debasement of art reminds those of us who have cultivated in ourselves the ability to have powerful aesthetic experiences that real art encounters always are private and unfolding, never imported; that we are not social beings only; that artworks engage the mind in the broadest sense, as well as the body and spirit. So long as experts remain ignorant about the terms of the art encounter, we are best off disregarding them.

1 note

·

View note

Text

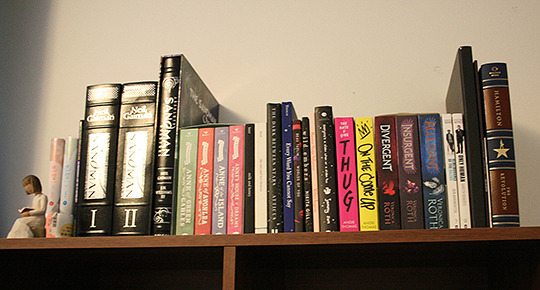

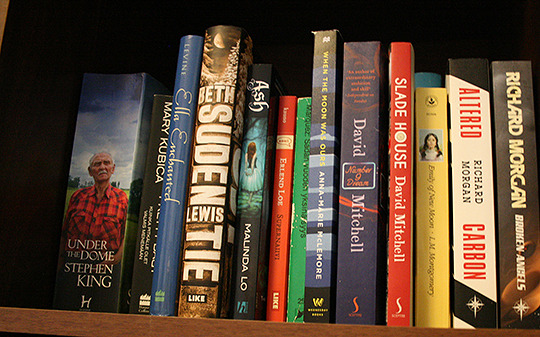

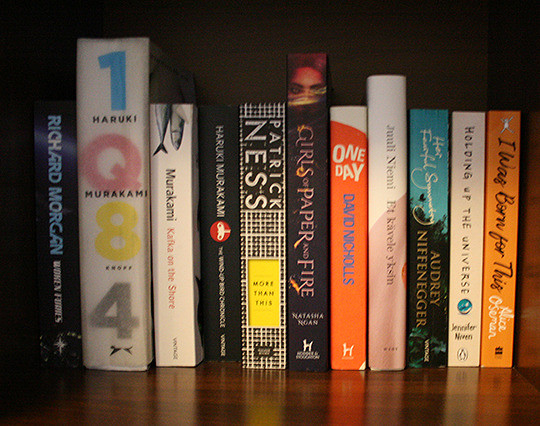

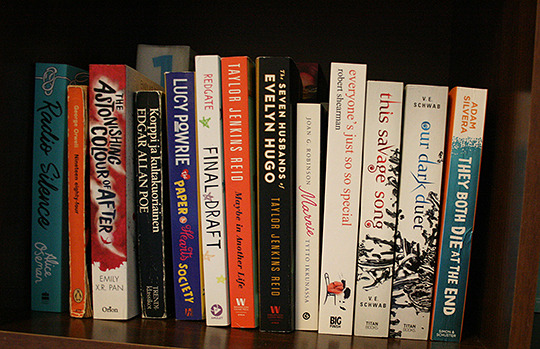

it’s not munday yet but since @colourinthesky thought it was, i can also let myself think it is, and share my bookshelf for munday. :DDDDD i reorganized my/our (dean hasn’t moved in yet but some of his books are here and what’s mine is his and the other way round) bookshelf, it’s mostly alphabetical order now (because i got lazy) with nonfiction, some books that stand easily above the bookshelf with poetry, separated.

Top shelf:

恋空 parts 1 & 2 by 美嘉

Love Beyond Body, Space, And Time: An Indigenous LGBT Sci-fi Anthology by several authors

Sandman Omnibus I, II, and Sandman: Overture by Neil Gaiman

Anne of Green Gables, Anne of Avonlea, Anne of the Island and Anne’s House of Dreams by L.M. Montgomery

milk and honey and the sun and her flowers by Rupi Kaur

The Dark Between the Stars by Atticus

Every Word You Cannot Say by Iain S. Thomas

Worlds of You: Poetry and Prose by Beau Tablin

wild embers by Nikita Gill

Kiltin kapina by Hanna-Maija Valjanen (self-published poetry in Finnish by an old friend)

everyone’s a aliebn when ur a aliebn too by Jomny Sun

The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

On the Come Up by Angie Thomas

Divergent, Insurgent and Allegiant by Veronica Roth

Remembrance of the Daleks by Ben Aaronovitch

Only Human by Gareth Roberts

Untitled Supernatural fanart book by several artists

Profound Zine vol. 1 (it’s a Destiel zine, I wasn’t writing for this volume but am for vol. 2)

Hamilton the Revolution by Lin-Manuel Miranda and Jeremy McCarter

Non-fiction shelf:

Shibari You Can Use: Japanese Rope Bondage and Erotic Macramé by Lee Harrington

The New Bottoming Book and The New Topping Book by Dossie Easton and Janet W. Hardy

Drawn to Sex: The Basics by Erika Moen and Matthew Nolan

The Threesome Handbook by Vicki Vantoch

The Ethical Slut by Dossie Easton and Janet W. Hardy

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

No Plot? No Problem! by Chris Baty

On Writing by Stephen King

Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents by Lindsay C. Gibson

You’re Never Weird on the Internet (almost) by Felicia Day

Girl, Interrupted by Susanna Kaysen

I am Malala by Malala Yousafzai

Life Lessons from Winnie-the-Pooh by Janette Marshall

Culture Shock! Finland: A Guide to Customs and Etiquette by Deborah Swallow (blame Dean)

Dean’s German textbooks by whoever (SORRY I AM LAZE)

The Anxiety and Phobia Workbook by Edmund J. Bourne

Why Time Flies by Alan Burdick

In Search of Schrödinger’s Cat by John Gribbin

Seven Brief Lessons on Physics by Carlo Rovelli

Kotona Maailmankaikkeudessa by Esko Valtaoja

Dance of the Photons by Anton Zeilinger

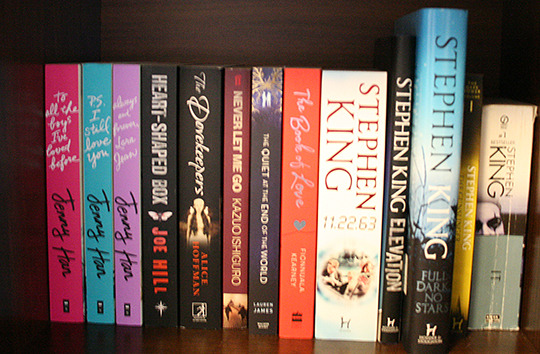

(more) fiction shelves:

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams

Down and Across by Arvin Ahmadi

What If It’s Us by Becky Albertalli and Adam Silvera

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

Annabelle by Lina Bengstdotter

Starfish by Akemi Dawn Bowman

Summer Bird Blue by Akemi Dawn Bowman

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Angels and Demons by Dan Brown

The Guitar by Michel del Castillo

Ready Player One by Ernest Cline

The Supernaturalist by Eoin Colfer

Can’t Look Away by Donna Cooner

Skinny by Donna Cooner

Out of My Mind by Sharon M. Draper

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald

Sophie’s World by Jostein Gaarder

Inkheart, Inkspell and Inkdeath by Cornelia Funke

Follow Me Back by A.V. Geiger

Once by Morris Gleitzman

The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

The Fault in Our Stars by John Green (dean do we really want to keep this problematic cancer romaticizing antisemitic piece of... a lot of our books are problematic, tried not to say anything about any single one, but.)

Looking for Alaska by John Green

Paper Towns by John Green

Turtles All the Way Down by John Green

The Reality Dysfunction by Peter F. Hamilton

To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before, P.S. I Still Love You and Always and Forever, Lara Jean by Jenny Han

Heart-Shaped Box by Joe HIll

The Dovekeepers by Alice Hoffman

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

The Quiet at the End of the World by Lauren James

The Book of Love by Fionnuala Kearney

11.22.63 by Stephen King

Elevation by Stephen King

Full Dark No Stars by Stephen King

The Gunslinger by Stephen King

IT by Stephen King

Under the Dome by Stephen King

Pretty Baby by Mary Kubica

Ella Enchanted by Gail Carson Levine

The Wolf Road by Beth Lewis

Ash by Malinda Lo

Naïve. Super by Erlend Loe

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

When the Moon Was Ours by Anna-Marie McLemore

Number 9 Dream by David Mitchell

Slade House by David Mitchell

Emily of New Moon by L.M. Montgomery

Altered Carbon, Broken Angels and...

Woken Furies by Richard Morgan

1Q84 by Haruki Murakami

Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami

The Wind-up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami

More than This by Patrick Ness

Girls of Paper and Fire by Natasha Ngan

One Day by David Nicholls

Et kävele yksin by Juuli Niemi

Her Fearful Symmetry by Audrey Niffenegger

Holding Up The Universe by Jennifer Niven

I Was Born for This by Alice Oseman

Radio Silence by Alice Oseman

1984 by George Orwell

The Astonishing Colour of After by Emily X.R. Pan

A collection of stories by Edgar Allan Poe

Paper & Hearts Society by Lucy Powrie

Final Draft by Riley Redgate

Maybe in Another Life by Taylor Jenkins Reid

The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo by Taylor Jenkins Reid

When Marnie Was There by Joan G. Robinson

Everyone’s Just So Special by Robert Shearman

This Savage Song and Our Dark Duet by V.E. Schwab

They Both Die at the End by Adam Silvera

Not Before Sundown by Johanna Sinisalo

Kädettömät kuninkaat ja muita häiritseviä tarinoita by Johanna Sinisalo

Hearts Unbroken by Cynthia Leitich Smith

The Fire Chronicle by John Stephens

Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandell

The Dreamers by Karen Thompson Walker

The Strange and Beautiful Sorrows of Ava Lavender by Leslye Walton

Paper Girl by Cindy R. Wilson

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

March is the month that disappeared! I haven’t been up to much as my health’s not great at the moment and yet the days have flown by. I have been doing lots of reading – mainly audio books as my eyes are still not great – but some print books too. I’m trying to spend less time looking at screens so apologies if I haven’t commented on your posts or shared things as often recently. I hope to get back to it soon.

Here are the 23 that books I read in March:

Ordinary People by Diana Evans

I’d had this book on my NetGalley shelf for almost a year but I finally picked it up in March and I loved it so I’m kicking myself for not reading it sooner. I will review it soon but in the meantime I definitely recommend it!

Sewing the Shadows Together by Alison Baillie

I loved this crime novel, it has such a good sense of place and great characters. I’ve already reviewed this one so click the title above if you’d like to know more.

Don’t You Cry by Cass Green

I listened to this on audio and it was an okay listen. I enjoyed it while I was listening but it’s not a book that’s really stayed with me.

Past Life by Dominic Nolan

This book is so good! It has so much depth to it and kept me hooked all the way through. I’ve reviewed this one so click the title to find out more of what I thought.

Welcome to the Heady Heights by David F. Ross

This book is so hard to define but it was impossible to put down! I really enjoyed it. My review is already up so click the title to learn more.

Entanglement by Katy Mahmood

I had this book on my NG but I also got the audio book so part read and part listened to it. I very much enjoyed this one and hope to get my review finished and posted soon.

The Guilty Party by Mel McGrath

This book is so good! It grabbed me from the first page and had me gripped right to the very end. I’ll be reviewing this one soon too!

Beautiful Bad by Annie Ward

This is another really good read! I think I read this in one sitting pretty much and love how even though I thought I had it all sussed there was more to come! My review is posted so please click the title if you want to know more.

Hold My Hand by M. J. Ross

I downloaded this on audio after reading Meggy’s great review of the second book in the series. I loved this and already have the next book on my phone to listen to soon!

Not Fade Away by John Gribbin

This was a really enjoyable book looking at the music of Buddy Holly.

Goodnight Malaysian 370 by Ewan Wilson

I got this one on my Kindle Unlimited free trial and it was an interesting read but there was nothing in it that I hadn’t already read from articles online.

Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward

I’ve had a copy of this on my NG shelf for way too long so when I spotted the audio book on my Scribd trial I decided to listen to it while reading. I adored the writing in this novel and will definitely be looking to read more Jesmyn Ward in the future.

The Flower Girls by Alice Clark-Platts

This book was brilliant! I finished it a couple of weeks ago but it’s still going round in my head. I will be reviewing it once I get my thoughts together but in the meantime I recommend it!

White Lies by Lucy Dawson

I listened to this on Audible and really enjoyed it. It was gripping and I was keen to find out who was telling the lies!

The Flight Attendant by Chris Bohjalian

I listened to this one on Scribd too. It’s a book I’ve wanted to read for ages and I enjoyed it but it’s not the best book by the author.

It Happens All The Time by Amy Hatvany

This was also a Scribd listen and I was engrossed all the way through this book. It’s a great read and it really makes you think as you listen to both sides in the aftermath of a sexual assault.

The Conviction of Cora Burns by Carolyn Kirby

This book is incredible and I feel sure it will be in my top books of the year. I was utterly absorbed in the story and I feel sad to have finished it. I highly recommend it and if you want to know more click the title for my review.

C is for Corpse by Sue Grafton

I’m slowly re-reading all of this series so when I found this one on Scribd I decided to listen to it. It’s not my favourite in the series but I enjoy all of the books. Kinsey Millhone is great!

The Point Of Poetry by Joe Nutt

This book gave me some of my confidence back for reading poetry and got me to see poems I already knew in a new light. I recommend this book to everyone! Click the title to read my full thoughts.

Call Me Star Girl by Louise Beech

This book is stunning! I loved every single second that I spent reading it and I’m sad to have finished it. This is also a contender for my top books of the year!

Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson

I’ve wanted to read this one for a while so when I saw it on Scribd I decided to listen to it. It’s a brilliant book and I now want to get a physical copy to have on my bookcase.

Milkman by Anna Burns

I had the book of this but decided to listen to the audio while also reading it and I completely and utterly adored it. I feel like my thoughts on this book will keep developing for a while but I 100% recommend it!

55 by James DeLargy

I finished this book yesterday and I’m still thinking about that ending! This is such a good read, it’ll be one that stays with me!

March Blog Posts & Reviews:

#gallery-0-51 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-51 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 25%; } #gallery-0-51 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-51 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

That Was The Month That Was… February

Stacking the Shelves on 2 Mar

Mini Book Reviews of The Trick to Time by Kit de Waal, Dear Mrs Bird by A. J. Pearce, Ivy and Abe by Elizabeth Enfield and Someone Like Me by M. R. Carey

Review of The Bridal Party by J. G. Murray

#gallery-0-52 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-52 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 25%; } #gallery-0-52 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-52 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

This Week in Books 6 Mar

Review of Last Ones Left Alive by Sarah Davis Goff

Stacking the Shelves 9 Mar

Review of Are You The F**king Doctor? by Dr. Liam Farrell

#gallery-0-53 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-53 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 25%; } #gallery-0-53 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-53 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Review of Past Life by Dominic Nolan

Review of Sewing the Shadows Together by Alison Baillie

This Week in Books 13 Mar

Review of Welcome to the Heady Heights by David F. Ross

#gallery-0-54 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-54 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-54 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-54 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Stacking the Shelves 16 Mar

This Week in Books 20 Mar

Review of Beautiful Bad by Annie Ward

Stacking the Shelves 23 Mar

#gallery-0-55 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-55 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 25%; } #gallery-0-55 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-55 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Review of The Conviction of Cora Burns by Carolyn Kirby

This Week in Books 27 Mar

Review The Point of Poetry by Joe Nutt

Stacking the Shelves 30 Mar

The state of my TBR:

So I said in my February TBR update that my plan to reduce my TBR had gone somewhat awry. Well, in March it’s done waaay beyond that! Ooops! My plan was to reduce my TBR each month so that by the end of the year it would have 200 fewer books on it. At the end of February it was at 2482 and now it’s at 2500. That doesn’t seem too bad but it should be at 2387 if I was sticking to my plan. Ah well, I can’t really complain about having lots of lovely books to read. 🙂

How was March for you? I hope you all had a good month and that you read lots of good books. Did you read many books? What was your favourite book of the month? Please tell me in the comments, I’d love to know. Also, if you have a blog please feel free to leave a link to your month’s wrap-up post and I’ll be sure to read and comment back. 🙂

That Was The Month That Was… March 2019! March is the month that disappeared! I haven't been up to much as my health's not great at the moment and yet the days have flown by.

#55#A. J. Pearce#Alice Clark-Platts#Alison Baillie#Amy Hatvany#Anna Burns#Annie Ward#Are You The F**king Doctor?#Audiobook#Beautiful Bad#Books#Brown Girl Dreaming#Buddy Holly#C is for Corpse#Call me Star Girl#Carolyn Kirby#Cass Green#Chris Bohjalian#David F. Ross#Dear Mrs Bird#Diana Evans#Dominic Nolan#Don&039;t You Cry#Dr Liam Farrell#ebooks#Elizabeth Enfield#Entanglement#Ewan Wilson#Goodnight Malaysian 370#Hold My Hand

1 note

·

View note

Quote

The empathy racket treats as automatically canonical any art that memorializes certain historical events, art as documentary, and art of witness, whatever its quality or degree of originality. Those forces inexplicable to the human, which great art from Hellenistic sculpture to the Jodhpur-Marwar court paintings to Modernist poetry has concerned itself with—forces unconscious, spiritual, natural, chthonic—do not interest the empath.

From “The Empathy Racket” by Alice Gribbin

0 notes

Text

Groundhog day in the hothouse

On 6 August Will Steffen and others published a paper entitled “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene”. The paper explores “the risk that self-reinforcing feedbacks could push the Earth System toward a planetary threshold that, if crossed, could prevent stabilization of the climate at intermediate temperature rises and cause continued warming on a ‘Hothouse Earth’ pathway even as human emissions are reduced”. This caused some stir, summarised to some extent by Ken Rice here.

Hothouse language

In a piece for The Conversation Richard Betts wrote: “Personally, I found this an interesting and important think piece that was well worth reading. But since this is not actually new research, why is it getting so much coverage? I suspect that one reason is the use of the vivid ‘Hothouse Earth’ term at a time when everyone’s talking about heatwaves. Another is that it’s clearly a dramatic narrative, and not surprisingly this has led to some sensationalist articles.”

This prompted Alice Bell to ask some questions about language! She tweeted “In his Conversation piece, Richard implies that the term ‘hothouse earth’ isn’t exactly a scientific contribution, more a comms one. And that’s a fair enough view. Still, not sure I agree.” She added: “terms like ‘Hothouse earth’ come from science and are woven into how the world works with that science, so maybe we’re better off admitting it’s part of our biz and working from that?”. Exactly, I thought. As I have written about the ‘greenhouse effect’ and the ‘carbon footprint’ metaphors before, I became curious about ‘hothouse earth’ and where that metaphor came from and when it was first used.

Tracing the hothouse earth metaphor

In his column ‘word of the week’, Steven Poole rightly points out that the term ‘greenhouse effect’ was coined in 1907 and continues: “a ‘hothouse’ sounds far more intense. From the 16th century, a hothouse was a bathhouse or a brothel, or a heated room for drying linen, and then a heated greenhouse for cultivating exotic species, metaphorically extended to an environment in which anything (including minds) grows very quickly. Its products are often said to be highly delicate, if not sickly. We are already wilting like hothouse flowers this summer, and there might be no way to smash the glass.” He doesn’t say when the metaphor ‘hothouse earth’ was coined. We’ll come back to that.

For most gardeners a hothouse basically means a heated greenhouse in which plants that need protection from cold weather are grown. That doesn’t sound so bad. The metaphor ‘hothouse earth’, however, focused away from the protection and onto the dangers of destruction from overheating, as highlighted by Poole.

This seems to be related to a scientific/geological definition I found on Wikipedia linked to a distinction between greenhouse/hothouse and icehouse earth: A “’greenhouse Earth’ or ‘hothouse Earth’ is a period in which there are no continental glaciers whatsoever on the planet, the levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (such as water vapor and methane) are high, and sea surface temperatures (SSTs) range from 28 °C (82.4 °F) in the tropics to 0 °C (32 °F) in the polar regions.” This meaning seems to have appeared at the end of the 1990s in the geological literature.

Hothouse earth in the media

However, I wondered when this metaphor was first used publicly and for a quick forage I looked at Lexis Nexis. I found that it was first used well before the 1990s in 1975 in a brief report in the New York Times. I quote it in full, as it is quite interesting. Hot or heat seems to refer here to ‘heat’ as such, not carbon dioxide emissions (the abbreviations and typos in the article are not mine).

“Dr Howard A Wilcox, in bk ‘Hothouse Earth,’ says man’s output of heat into atmosphere, if allowed to continue to increase at present energy and indus growth rates, will raise earth’s temperature enough to melt polar ice caps and flood many populous areas of earch in next 80-180 yrs; man current puts heat into atmosphere at about 1/10,000 rate at which sun is contibuting heat to earth (5,000-billion-billion BTU’s annually); Wilcox says that present growth rate of energy consumption (4-6% a yr) will result in 80 yrs in mankind’s returning to atmosphere approximately 1/100 of total amount of energy transmitted by sun, raising worldwide temperature 1-3 degrees; even 1-degree rise, through a falling-dominoe kind of reaction, could melt ice caps; Dr William W Kellogg of Natl Center for Atmosphere Research doubts energy consumption will continue to grow at exponential rate; Dr J Murray Mitchell Jr of NOAA see more immediate danger in increasing amounts of carbon dioxide that are thrown off into atmosphere along with heat (M)”

The domino effect metaphor returned this year alongside tipping points after the publication of the recent hothouse article. (On tipping points in the media, see here)

After 1975, 37 news items used the metaphor ‘hothouse earth’, with a tiny peak in 1990 when eight articles appeared. This is as nothing compared to the 276 articles that were published between 6 and 10 August 2018.

Groundhog Day in the hothouse

The little peak in 1990 was prompted by a book written by John Gribbin and entitled Hothouse Earth: The greenhouse effect and Gaia. When looking a the coverage of that book in the news, I was surprised yet again to find that even then the SAME OLD issues dogged climate change as now.

One reviewer, Keith Spoeneman, for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri) (13 May, 199) noted: “That the average global temperature will likely rise by some 5 degrees Fahrenheit over the next 40 years, and that the oceans will rise 1 or 2 or possibly more feet in this same period, should come as no surprise to anyone with an awareness of the many scientific warnings that have been voiced on this subject since the unprecedentedly warm decade of the 1980s. But controversy and a powerful inertia have always dogged these warnings. Every few months, it seems, some new objection is raised, and almost regardless of the scientific response, the political response is a continued wavering and an ever-renewed call for more study of the ‘problem.’”

Solutions to ‘the problem’ were already discussed in the 1975 hothouse earth book by Wilcox, who points out: “Immediate development of solar energy technology to produce solar energy cells, windmills, and ocean turbines combined with open-ocean farming are steps that can be taken to avoid a thermal catastrophe.” Back to, or rather forward again to, 1990.

Another reviewer of the Gribbin book, William Goulding (The Sunday Times, 28 January, 1990), quotes the late climate scientist and climate science communicator Stephen Schneider as saying: “scientific predictions are like ‘trying to gaze into a dirty crystal ball. By taking time to clean the glass you can get a better picture; but at some point it is necessary to decide that the picture is good enough to alert policy makers and the general public to the hazards ahead. That point has certainly been reached with studies of the greenhouse effect and the prospect of rising sea levels in particular.’’” Unfortunately, that point seems to be forever receding into the future…

Maintaining a Goldilocks house

I won’t analyse the mass of articles that have been published in 2018 following the recent use of the hothouse earth metaphor. I just want to say: The earth is our ‘house’. It can be an ‘icehouse’; it can be a ‘greenhouse’; it can be a ‘hothouse’. At the moment we live in a still relatively nice greenhouse of which Goldilocks would be proud, but a greenhouse that’s gradually overheating if we don’t do something about our own foolish actions that led to the greenhouse overheating in the first place.

That’s basically what the Will Steffen et al. paper tried to say, I think. It should be stressed though that the authors wanted to point out a “risk that needs studying, not something that is certain to happen” (New Scientist). But we better make certain that we do both, study what’s going on and deal with the enhanced greenhouse effect that has been our own doing, i.e. reduce emissions.

Image: Pixabay

The post Groundhog day in the hothouse appeared first on Making Science Public.

via Making Science Public https://ift.tt/2B3djvv

0 notes

Text

Latest Art Mooching

In Mayfair.

Vie au sol, mars 1955

A Festival of the Mind

Jean Dubuffet at Waddington Custot to 27 June 2018

Installation shot

Paysage rose avec 3 Persongaes de noir 1975

Installation shot

Voie pietonniere 1981

(detail)

Castelet L’Hourloupe (vue de l’Est) 1968

Julien Opie

at Alan Cristea Gallery to 16 June 2018

Headphones, telephone, Cardigan, Handbag, Backpack, Plastic Bag, Jacket 2018

Modern Towers 1 - 3, 2017,

Gribbin Head 2017

Lantic Bay 2017

Polridmouth Coast 2017

Nobody

Alice Oswald/William Tillyer at Bernard Jacobson Gallery to 23 June 2018

From The PRESS RELEASE: Nobody, a collaboration between the acclaimed British artist, William Tillyer and Alice Oswald, widely regarded as the finest living British poet.

Nobody’ is an alias of Odysseus, one of his lost selves, adrift and unable to get home. Oswald’s words are his rhapsody, a circling shoal of sea voices which ends where Homer’s epic begins. Caught between The Odyssey and The Oresteia and not knowing either story’s conclusion, the poet goes on speaking surrounded by water. Perhaps he is only an alias of Odysseus, one of his lost selves, unable to get home?

This poem is a circling shoal of sea voices, inspired by Homer’s descriptions of the sea – ‘the bodiless or unbounded thing’ which ends at The Odyssey’s beginning whilst the paintings immerse us in a visionary experience of an elusive, almost abstract, lyrical and romantic world. Springing from Tillyer’s belief in the shared essence of all things, the paintings are a tangible accompaniment to Oswald’s poem, explored through paper, water, and pigment, resulting in a single dazzling work of words and watercolour.

Seung-taek Lee

at White Cube Mason's Yard to 30 June 2018

Untitled 1974

From the PRESS RELEASE: As one of the first generation of South Korean artists to embrace radical experimentation in art, Lee has been at the forefront of the Korean avant-garde since the 1960s. Although formally trained as a sculptor, Lee is best known for his practice of negation, which he has alternatively conceptualised as ‘non-sculpture’, ‘non-material’ or ‘anti-concept’. As an acute response to and reaction against rapidly transforming conditions in South Korea - from its emergence as a divided nation following three decades of Japanese colonialisation (1910-45) and the Korean War (1950-53), to its development into a modernised, global nation - Lee’s work has persistently unsettled established forms of contemporary Korean art. Yet his locally-specific experiments, especially those of the 1960s and 1970s, invite comparison with other contemporaneous movements such as Land Art, Art Povera and Post-Minimalism.

Untitled 2016

Detail

Drawing 2015

Godret Stone 1958

Untitled works 1963/2018

0 notes

Text

At the link above, please find Alice Gribbin on how "the relation of art and politics is incidental, not inherent," with references from the cave wall to Guernica, Toni Morrison to Alice Neel. Don't miss the point about how bad political art—simplistic, moralizing, and didactic—ruins politics as well as art. And see also her postscript, which tells the story of George Oppen to argue against the idea of a politics of form (personally, I go back and forth over whether or not there is a politics of form):

One might say that Oppen is an important poet still because the United States is always at war, its citizenry always implicated in the bloodstained project of imperialism. Or, instead, one could say Oppen is important now as then because his worldview, like that of all great poets, is worth the effort of meeting and challenging, taking from and being burdened with.

(I've never read any more Oppen than Louise Glück quoted in Proofs and Theories, but this is the second time in a month I've run into him—Emmalea Russo also cites him in Confetti—so it's evidently time for me to take him up.)

1 note

·

View note

Note

Thoughts on Ezra Pound's literary criticism?

It's great. (I wrote a bit about Pound this week in my weekly newsletter, by the way.) I was just reading or rereading some of the Literary Essays volume in light of Alice Gribbin's Manifesto! appearance, but ABC of Reading is the book I've been carrying around since high school. His basic precepts—direct treatment of the object, avoidance of rhetoric and abstractions, using the least number of words necessary for the desired effect, the maintenance of music and rhythm without the crutch of a regular meter—still dominate more than anyone else's precepts the way we write, even prose and even to this day, no matter how many learned cultural historians draw out the connection between his later politics and these aesthetics, with their emphasis on purifying the language of the "tribe," an anti-Miltonic and anti-Romantic stance that is also by extension an anti-democratic one. Still, with these precepts, however "problematic," he opened eastern and re-opened medieval aesthetics for the 20th century. (As is often the case, multiculturalism and fascism go hand in hand.) His greatest acts of practical criticism were his edits on The Waste Land and on Yeats's work. He made two of the three greatest poets in English in his century—and to whatever extent Stevens was reacting against him, then he even by negation made Stevens, too. He might have come in fourth himself, depending on how one feels about Frost, Auden, Moore, Williams, Bishop, Lowell, Plath, Heaney, Walcott, etc. He was one of the creators of his artistic century, too big to ignore or dismiss.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

—Alice Gribbin, “The Empathy Racket”

The best polemic against the empathy trend yet. The valorization of empathy may have had a more damaging effect on politics than art: for example, that thread of Twitter libs saying “there’s no such thing as a fascist intellectual,” which shows a disastrous misunderstanding of modern culture’s tragic dimension, as if there were no necessity whatever to wrestle with Lawrence, Yeats, Heidegger, Pound, etc. But it also demonstrates that liberals can no longer conceive of ideology, philosophy, or religion as political motives. Disagreement becomes nothing more than a failure of feeling, not a different and holistic set of assumptions, premises, and arguments according to which what one person deems good, another deems bad, both of them validly from within their own logic. This is why contemporary left-liberals treat art and culture as central to social engineering: they literally want to reprogram people’s emotions, since they see them (falsely) as the seat of the political.

If empathy can be heckled out of its present hegemony, I hope we can restore it to its proper place in art: as the (amoral) speciality of the psychological novel, which gives curious readers an insight into the unspoken and unspeakable tides of thought and feeling that actually roll through the psyche when we’re not applying for grants or teaching positions:

She felt somehow very like him—the young man who had killed himself. She felt glad that he had done it; thrown it away. The clock was striking. The leaden circles dissolved in the air. He made her feel the beauty; made her feel the fun.

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

If you’re not subscribed on SubStack or the podcasting platform of your choice—and, honestly, if not, why not?—above is the third episode of Grand Podcast Abyss for our audiovisual Tuesday. We’re a bit more casual in this one, perhaps even ribald, as Sam grills me about one of my more esoteric posts right here on Tumblr. Here’s the official description:

General hilarity. Sidney Morgenbesser, Mencius Moldbug, Judith Butler. Nietzsche. Limits of thought. Cheapness of paradox. How to write. Hannah Arendt contra contemporary liberalism. More Mailer. Left conservatism. Charlie Hebdo.

Interestingly, this was recorded weeks ago, before the Art Spiegelman and Joe Rogan censorship controversies, yet somehow we got to talking about Charlie Hebdo as the moment the left decisively abandoned freedom of speech and art. In his survey of artistic “boot-licking” at Tablet, Armin Rosen likewise raises the issue:

It was artists who led the charge against Charlie Hebdo being given an award by PEN after much of its staff was massacred in 2015—a statement opposing the honor was signed by such literary celebrities as Joyce Carol Oates, Michael Ondaatje, Teju Cole, and Junot Díaz. According to these writers, dying for the cause of free expression didn’t deserve recognition if the expression itself might be taken the wrong way.

As I say on the pod, I read the episode as the moment when the literary left, having relinquished any ability to police aesthetics per se with the postmodern demolition of all artistic hierarchies, were forced to equivocate not only about state censorship but even the freelance murder of artists so long as the political justification was plausible. Awful cartoons, if you ask me—each of the world’s great religions is a Gesamtkunstwerk spanning centuries or millennia and deserves better, even or especially in the way of critique, than scrawlings that belong on the wall of a public toilet—but in the face of an anti-civic murder spree, we have to keep our sense of proportion. Similarly, I don’t even listen to Joe Rogan, but the call to silence his querying of government policy is coming from the government itself, so, as a matter of principle, what choice do I have but to state my support for him?

Finally, to put these questions in a broader context, let me recommend the latest from Alice Gribbin, on what “art-for-art’s-sake” does and doesn’t mean. I appreciate the essay’s quiet anti-academic thrust—the skepticism that the conversation has to begin with Kant rather than artists’ work itself, the dismissal of “the more enervating strains of Marxist critique” for which “art is no different from journalism or factory parts”—as well as its ultimate implication of an aesthetic drive operating independently in the psyche. She quotes Twilight of the Idols. Nietzsche cautions us not to let a righteous challenge to moralism become a resentful refusal of life:

The struggle against purpose in art is always a struggle against the moralizing tendency in art, against the subordination of art to morality. L’art pour l’art means: “the devil take morality!” — But this very hostility betrays that moral prejudice is still dominant. When one has excluded from art the purpose of moral preaching and human improvement it by no means follows that art is completely purposeless, goalless, meaningless. . . . Art is the great stimulus to life: how could it be thought purposeless, aimless, l’art pour l’art?

This is the great paradox (I expended almost 300 pages of academic prose trying to elucidate it myself): that only if art is allowed to be for itself can it be good for anything else, which is to say, for us. “The art itself is nature.”

#podcast#literature#literary criticism#free speech#censorship#aestheticism#charlie hebdo#alice gribbin#friedrich nietzsche

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Bartłomiej Pękiel - Dulcis amor Jesu·

The Sixteen : Eamonn Dougan · Charlotte Mobbs · Alice Gribbin · Jeremy Budd · Matthew Long · Stuart Young

1 note

·

View note