#also ive gone through all the unfinished pages

Text

CANT CATCH ME NOW ?! - leaving them behind

they see you everywhere. james, jonggun, joongoo. they find bits and pieces of you lying around in their pockets, their houses and memories. it depends on which one it is which scene they see you in.

DG VER. gun ver. goo ver.

for james, he sees the sight of you in the crowd when he first started as an idol. he catches himself hoping for a glimpse of you in crowds as he did before. maybe you just show up at one of his concerts one day. he knows its a childish hope to think you'll come back. especially not when theyve all pushed you out of their lives.

but was it such a hopeless thought to have? a particulary fond memory of seeing you in the front row at barricade. hopping down and singing his lyrics to your face. fans thought you were just a really lucky person to catch the attention of DG, minimizing it to a harmless fan interaction moment just for the concert.

he loved the way your eyes twinkled underneath the stage light illuminating your face in a mesmerizing glow. he recalled the heartbreak when they were all gathered up at your apartment.

it had become a haunting memory of seeing the house abandoned. the only thing left was a small ragged old scarf you insisted on keeping

"yknow! one day for my super awesome snowman! ive been waiting for winter to come in korea so snow is finally here!" you tell him with a giddy grin at the mall. your loose baby strands around your face and your face bare with nothing on it standing out to him.

you always mentioned you wanted to experience the snow. you said you didnt have it where you were from. far too sunny for that you said.

"you wont have to wait long. it get cold fast in korea" he tells you. chuckling as you hold the scarf in your hand while picking out more winter items.

how unfortunate. it was snowing right now. he wondered where youve gone. maybe youve died off, its better for him that way. that way he wont have to think about whether or not youve settled down yet. maybe gone back to your old country or somehwere new.

maybe youre out on a date somewhere, possibly 6 feet down in a ditch. his mind wanders when it comes to you.

reading the note you left behind for him. written in a sparkly pen you always used.

"why do you have so many pens and only use one?!" he questions you with a raised eyebrow. his long fingers unzipping your pencil pouch and looking through all the pens you own.

"you cant expect me to use all of them. plus my papers look sparkly this way and its cute. the design is cute and i like how it writes!" you chirp at him. turning behind you and hitting his forehead with your pen. "red hair... i like you with your curly red hair. reminds me of someone i used to know" you tell him.

curling his hair around your pen before dropping it when you hear the teacher say your name and turning back to the board. your hair whipping him in the face "im innocent!" you joke with your hands raised causing the class to laugh.

you tell him youre sorry in the note. that you couldnt handle it anymore.

you tell him everything but telling him nothing at the same time. telling him of how you felt like everyone else was moving while you were stuck in the present. everyone was special and you were not.

he let the paper drop down after skimming the rest of its contents. he wished to just crumple it up and tossed it away. he couldn't.

he knew he was being selfish wanting you back when youve clearly stated in the note this was out of youre pure will, leaving them behind. he wouldve cried. he wouldve cried if he was james lee.

all he could do was pick it back up and meet back with gun, and goo.

it was gonna all be in one set page but i found that it was longer than most of my other projects if i actually completed this whole

so i broke it up

like the friend group

ha

i caught up with lookism

i like the new pretty boys :3

ALSO QLSO I HAD AN ENTIRLY SEPRATE DOCUMENT FROM THIS AND I ACCIDENTALLY POSTED MY UNFINISHED STUFF BC I ACCIDETNALY POSTED IT INSTEAD OF COICKING DRAFT SO I HAD TO COPY AND PASTE ALL OF THIS PARAGRAPH BY PARAGRAPH TO THIS PAGE THINGY BC IM ON THE PHONE TYPING ALL PF US THIS SO A+ FOR WFFORT

did not proof read (bc im insecure abt my works 😔🤞)

#gun lookism#lookism x reader#lookism#gun x reader#goo x reader#james lee x reader#dg x reader#lookism scenarios#manhwa#manhwa x reader

230 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sonic BloodMoon [Chapter 1 Page 6]

[first] [prev] [next]

[Patreon]

#sonic fancomic#sonic the hedgehog#sonic bloodmoon#fun fact: the upcoming pages are some of my favourites so far#mostly bc of the colors ngl#next one especially#its got some vibes >:)#also ive gone through all the unfinished pages#and added the backrounds#like 80% of what makes coloring these so daunting is the backgrounds#so many bushes and trees#as far as the eye can see#truly it is hell

117 notes

·

View notes

Link

[I posted this essay to my blog The Heretic Loremaster over the weekend. Click the link above if you’d rather read it there. Reactions are welcome in both places.]

Who wrote The Silmarillion? It's a question with a more complicated answer than it seems on the surface. Yes, of course, J.R.R. Tolkien wrote the book that I picked up from a Barnes & Noble fourteen years ago, that is now on my desk with its cover coming off and its corners rounded from being read so many times. But who, in the vast imagined world within its pages, is telling the story? The narrator of The Silmarillion is so distant as to be barely discernible at all; it is possible to believe he doesn't exist at all. Indeed, in at least my first two readings, I did not think much of him. I assumed a distant, omniscient presence recounting what happened in plain, incontestable terms. Just the facts, ma'am.

The fact is, though, that J.R.R. Tolkien--the Silmarillion author whose name is on the cover--always imagined and constructed his stories not just as stories but as historiography: documents written by someone within the universe in which the history occurs. This complicates things: gone is the distance, the omniscience, and perhaps most importantly, the impression that the stories happened exactly as they are told.

This wouldn't be a problem--in fact, would be quite simple, as most fiction has point of view that is biased or unreliable--but for the fact that this isn't simple: This is Tolkien. So naturally, he had this idea that he wanted to write his stories as historiography, with a loremaster or chronicler who was himself a part of that history, but he couldn't make up his mind who this person was. In fact, he changed his mind several times, reversals that are documented in The History of Middle-earth for fans and scholars to angst and argue over.

I'm going to make the case that the "Quenta Silmarillion" is part of the Elvish tradition. This is contrary to the belief of Christopher Tolkien and other Tolkien scholars, who assign it to the "Mannish"--namely Númenórean--tradition. (@ingwiel has an excellent discussion of the evidence for this approach.) I understand why they did this, but I think that if you look deeply at the texts and the evidence those texts provide, there is not much to support that the tradition originated with the Númenóreans. (I am willing to concede that Elvish texts may have passed through Númenórean hands on their way back to Elrond and, eventually, Bilbo, but I persist in believing they are nonetheless predominantly Elvish texts representing an Elvish point of view.)

The Idea of the "Mannish" Tradition

The Elvish loremaster Pengolodh was first introduced as the primary author of the "Quenta Silmarillion" prior to 1930, when he was assigned author of the Annals of Beleriand (HoMe IV). Pengolodh was a tenacious character: Texts written as late as 1960 were still being assigned to him. So what happened?

The idea of the "Mannish" loremaster was a late idea and introduced as part of the series of writings collected by Christopher Tolkien under the title Myths Transformed (HoMe X). In a text that Christopher dates to 1958, Tolkien writes:

It is now clear to me that in any case the Mythology must actually be a 'Mannish' affair. ... The High Eldar living and being tutored by the demiurgic beings must have known, or at least their writers and loremasters must have known, the 'truth' (according to their measure of understanding). What we have in the Silmarillion etc. are traditions (especially personalized, and centred upon actors, such as Fëanor) handed on by Men in Númenor and later in Middle-earth (Arnor and Gondor); but already far back--from the first association of the Dúnedain and Elf-friends with the Eldar in Beleriand--blended and confused with their own Mannish myths and cosmic ideas. (Myths Transformed, "Text I," emphasis in the original)

To summarize: in 1958, Tolkien began to deeply question whether a civilization as advanced as that of the Eldar--a civilization that also had access to the teachings of the Ainur, who knew firsthand the structure of the universe--would produce myths that included such components as a flat Earth and the "astronomically absurd business of the making of the Sun and Moon" ("Text I"). This led to some radical cosmological rearrangements in Myths Transformed--and the relatively overlooked decision to reimagine the Silmarillion histories from a Mortal rather than an Elvish perspective. In an undated text also presented in Myths Transformed, Tolkien again takes up this question and explains the method of textual transmission in greater detail:

It has to be remembered that the 'mythology' is represented as being two stages removed from a true record: it is based first upon Elvish records and lore about the Valar and their own dealings with them; and these have reached us (fragmentarily) only through relics of Númenórean (human) traditions, derived from the Eldar, in the earlier parts, though for later times supplemented by anthropocentric histories and tales. These, it is true, came down through the 'Faithful' and their descendants in Middle-earth, but could not altogether escape the darkening of the picture due to the hostility of the rebellious Númenóreans to the Valar. ("Text VII")

"A leading consideration in the preparation of the text was the achievement of coherence and consistency," Christopher Tolkien wrote in a note on The Valaquenta in The Later Quenta Silmarillion II (HoMe X), "and a fundamental problem was uncertainty as to the mode by which in my father's later thought the 'Lore of the Eldar' had been transmitted."

Christopher Tolkien tentatively dates The Later Quenta Silmarillion II (LQ2) to 1958. Along with the last set of annals, The Annals of Aman and The Grey Annals, this represents the final version of the Silmarillion that his father produced. (See "Note on Dating" at the end of LQ2 in HoMe X.) Interesting about these texts--especially LQ2--is the fact that Tolkien removes all attributions Pengolodh. Mentions of Pengolodh are sprinkled throughout the Later Quenta Silmarillion I, which was written around 1951-52. When Tolkien "remoulded" LQ1 into LQ2, he removed Pengolodh. Also written around 1958? That first Myths Transformed text in which Tolkien asserts that his cosmology requires a Mortal and specifically bars an Eldarin loremaster.

And the Evidence of the Elvish, Part 1: The Creative Process

All this probably seems very simple. Tolkien was clear on his intentions. The Elvish tradition doesn't work, in his opinion. Therefore, it must be Mortal. He even took out the Elvish loremaster from the oldest Silmarillion draft. Simple, right?

Never. Working with any of the Silmarillion material--including the published Silmarillion--is necessarily speculative. This is a posthumous text, unfinished and existing in many forms. I think Christopher Tolkien did an admirable job of making a published book out of the tangle of his father's writings, but making that book required making decisions, as alluded to above, about how to decide what to include.

On this particular question, there are two approaches to making a decision on mode of transmission: There is Tolkien's stated intention, and there are the texts themselves and what they show of the realization of that intention. Christopher Tolkien, and many scholars, clearly prefer the first approach. Tolkien was clear on what he wanted, so that's the way to read the texts.

I prefer the second.

Perhaps this is because I approach the welter of Silmarillion texts as a creative writer as well as a Tolkien scholar. My experiences as an author of fiction myself lead me to question whether the creative process lends itself to the kind of neat analysis that says, "The author stated his intention. Here we have our answer." My experience tells me it is rarely that simple.

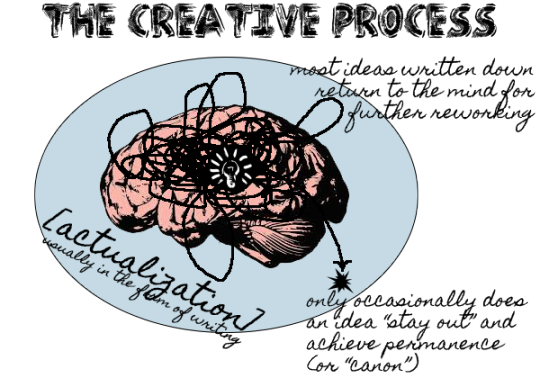

Below is what I imagine the creative process looks like for worldbuilding and constructing stories in that world, done in clipart and scribbles. For me, most of my work goes on in my mind: while driving to work, falling asleep at night, reading other authors' work, washing dishes, daydreaming. Some of the thinking is intentional, other occurs because it's where my mind wanders where I'm bored. Sometimes, thinking is sparked by an outside stimulus: an interview on the radio, a song, an image, a clip from a movie or TV. All of it goes into this tangle of thought constantly swirling in my mind, making and remaking my imagined world. Every now and then, an idea leaves my mind and takes concrete form as I write it down.

But only in limited instances do these ideas become finalized, incontrovertible--"canon," if you will. Sometimes an idea won't work and withers, unfinished. Other times, an idea is written down, only to dive back into the welter of thought in my mind for further reworking and reshaping--sometimes radically so.

Every author's creative process is different, of course, but hold up The Tale of the Sun and the Moon from the Book of Lost Tales next to the story Tolkien writes in Myths Transformed and the two are radically different, showing what any Silmarillion fan can tell you: Just because Tolkien wrote it down doesn't mean he meant it. Likewise, he went years at times without working on the legendarium, yet his letters and the progress we observe in the drafts show that he was always thinking about it. In short, his creative process, in this regard, seems a lot like mine.

Around 1958, we can say with some certainty that an idea crystallized from Tolkien's thoughts about his legendarium that the mode of transmission had to be centered on Mortals, not Elves. The idea seems to have loomed large in his awareness--along with ancillary ideas about cosmology--to the extent that it appears to reflect in decisions he made in revising LQ2.

But does that mean it is definitive? That it is "canon"? Not necessarily. In fact, I'd argue that we have proof that this particular manifestation of an idea was one that was far from finalized but dove back into the swirl of thinking on worldbuilding to be reconsidered and reworked--and ultimately unrealized.

And the Evidence of the Elvish, Part 2: Point of View

Point of view is no small thing in a story. In fact, in all but a few cases, it is so essential that to change the point of view risks breaking the story in a way that changing other elements rarely does. It's like painting. If you paint from the point of view of a peasant looking at a castle from the field where she labors, you cannot suddenly decide that the point of view is that of the princess looking out from the room in the castle where she spends most of her days, at least without redoing the painting entirely.

Likewise, one cannot take a story written from one point of view, then suddenly decide to change to a different point of view with any guarantee that the story will still work, much less make sense, without rewriting the story. In fact, in many cases, it will not.

Changing from an Elvish to a Númenórean point of view is not so simple as declaring, "Let it be!" and there it is. In the case of the "Quenta Silmarillion," the Eldarin (specifically Gondolindrim) perspective is deeply embedded. @grundyscribbling‘s post here is a good run-down of how the narrator's affiliation with Gondolin is revealed, even if never stated, in the stories included as part of the "Quenta." My article Attainable Vistas looks at some of the numerical data I've compiled that suggests a Gondolindrim perspective. At last year's Tolkien at UVM Conference, I presented more of that data, as well as new evidence that even the narrator's language in the "Quenta," reveals the point of view of a loremaster from Gondolin. Tolkien didn't put Pengolodh's biography down on paper until the 1959-60 text Quendi and Eldar, but the texts suggest that Pengolodh's identity was swirling in his mind many decades before that, and he wrote the "Quenta" with that point of view always in mind. Changing the point of view of such a story requires significant rewriting of the text. Do we have evidence that any of that rewriting--short of striking Pengolodh's name from LQ2--occurred?

No, we do not.

In fact, we sometimes see the opposite.

And the Evidence of the Elvish, Part 3: The Texts

The Later Quenta Silmarillion II becomes a relevant text to examine here because 1) it was written at the time when we know Tolkien was thinking about the mode of transmission and 2) his striking of Pengolodh's name from this version suggests he was beginning to act on his stated intention to revise the "Quenta" to reflect a Númenórean point of view. It is also an interesting text to study because it is a revision of LQ1, written about seven years earlier when the mode of transmission was, as far as I can tell, unreservedly Elvish.

Does the LQ2 contain other revisions toward a Númenórean mode? No, it is does not. In fact, it includes additions that, from a Mortal perspective, are suspect.

Laws and Customs among the Eldar. One of two major additions to LQ2 was Laws and Customs among the Eldar (L&C). L&C is explicitly attributed to Ælfwine, the Mortal man who was part of the mode of the transmission involving Pengolodh. Ælfwine is Anglo-Saxon, not Númenórean, but L&C is clearly written from the point of view of a Mortal commenting on Elves.

L&C opens with the sentence, "The Eldar grew in bodily form slower than Men, but in mind more swiftly." This comparison immediately establishes a Mortal point of view different from that of the "Quenta" as a whole, where Mortals are usually but supporting actors in a drama enacted by Elves. The first two paragraphs continue this comparison and assume the distinct point of view of a Mortal. Later, in the section "Of Naming," the narrator notes that the variety of names used by a single Elf "in the reading of their histories may to us seem bewildering," again establishing a Mortal point of view (emphasis mine).

L&C is an example of what a text written from a Mortal point of view would look like. "Men are really only interested in Men and in Men's ideas and visions," Tolkien wrote in Myths Transformed, and L&C acknowledges this by bringing Elvish customs into the context of Mortal experience ("Text I"). This text shows that Tolkien did manipulate the point of view based on his narrator. (This won't be shocking to any writer of fiction, and as an Anglo-Saxonist, Tolkien would have been aware of the impact of point of view on a historical text from that perspective as well.)

Christopher Tolkien dates L&C to the late 1950s (LQ2, "Note on Dating"). The argument could be made that Tolkien hadn't yet begun the process of revising to incorporate a Númenórean narrator. However, of all of the texts in LQ2, L&C is the easiest to revise to change the point of view. It is already from a Mortal point of view! Simply change the attribution to Ælfwine to a suitably Númenórean name and you have a major chapter of LQ2 aligned with the Númenórean mode of transmission. It is a surface change on the order of removing attributions to Pengolodh, and the fact that Tolkien didn't undertake it makes me question how seriously he truly undertook to revise the point of view.

The Statute of Finwë and Míriel. The Statute of Finwë and Míriel is the second major addition to LQ2. It is likewise dated to the late 1950s (LQ2, "Note on Dating"). If Tolkien wanted to write a text representing a Númenórean point of view, he couldn't have done a worse job of it with the Statute of Finwë and Míriel. Here we have a text deeply concerned with eschatology: Elven eschatology.

The Númenóreans were also concerned with eschatology. You could even say the Númenóreans were obsessed with eschatology, and immortality in particular. Here's a people, after all, annihilated because of their king's obsession with an Oasis song proclaiming, "You and I are gonna live forever!" A Númenórean text that represents Elven eschatology with no commentary grounding it in a Mortal perspective (like Tolkien does with L&C) is almost impossible to fathom. A text that centers on immortality and the decision to forgo immortality would certainly excite commentary from a Númenórean loremaster. Revisions to represent a Númenórean point of view would have to address this chapter--but they don't. Again, this suggests that JRRT's ideas about the mode of transmission weren't as definitive as his writings in Myths Transformed suggest.

And all the rest ...? Outside of L&C, the remainder of LQ2 includes nothing that suggests a Mortal point of view, even though L&C shows that Tolkien was capable, with the addition of a few words, of beginning to establish this. A convincing Númenórean text would have needed deep revisions, but surface changes--like the deletion of Pengolodh--set the course in the right direction.

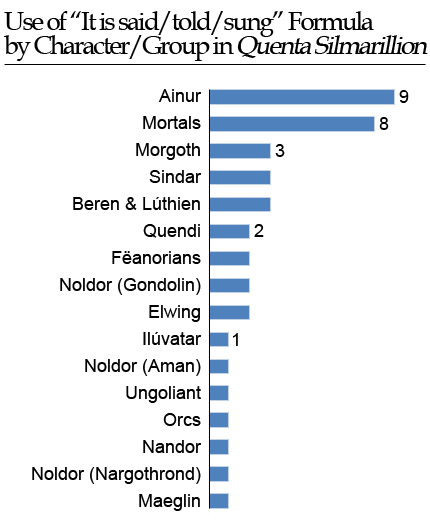

Throughout the "Quenta," Tolkien often uses formulas like "it is said," "it is told," and "it is sung" to indicate that the narrator is receiving information secondhand versus as an eyewitness account. As I discussed at the Tolkien at UVM Conference in 2017, these formulas are used primarily with the Ainur and Mortals. The image below shows the data from one of my slides from this presentation. Adding these formulas is a rather easy way to signal that the information the narrator is reporting is at a distance from him--and LQ2 uses them when reporting on the actions of Ainur to which even an Eldarin narrator could not have borne witness--yet Tolkien did not make these revisions. Instead, this part of the Silmarillion (originally attributed to Rúmil, who would have been present for this history) is written in the style of an eyewitness account, even though a Númenórean loremaster would certainly find these chapters of history the most distant and unattainable. Yet nothing in the style in which these chapters are written suggest this.

There is one passage in particular in the chapter "Of the Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor" that, like the Statute of Finwë and Míriel, seems a ripe opportunity to make revisions to signal a Mortal narrator if Tolkien desired to do so:

In those days, moreover, though the Valar knew indeed of the coming of Men that were to be, the Elves as yet knew naught of it ... but now a whisper went among the Elves that Manwë held them captive so that Men might come and supplant them in the dominions of Middle-earth. For the Valar saw that this weaker and short-lived race would be easily swayed by them. Alas! little have the Valar ever prevailed to sway the wills of Men; but many of the Noldor believed, or half-believed, these evil words. (emphasis mine)

It is hard to imagine a Mortal loremaster self-identifying as "weaker and short-lived" or offering up such an assessment without commentary. Yet this passage was brought over from LQ1--when the narrator was Elvish--without revision.

Another small passage again betrays the Elvish perspective: "But now the deeds of Fëanor could not be passed over, and the Valar were wroth; and dismayed also, perceiving that more was at work than the wilfulness of youth" ("Of the Silmarils," emphasis mine). According to the timelines in the Annals of Aman, Fëanor was about three hundred years old at this point. For a Mortal narrator--even a long-lived Númenórean one--to describe him as a "youth" is difficult to fathom.

Now one might claim that perhaps Tolkien just didn't get the chance to add material. It is one thing to remove Pengolodh but quite another to add content, even in a very brief form. However, he does add other content from Myths Transformed to LQ2: In the chapter "Of the Darkening of Valinor," he adds a reference to the "dome of Varda" that alludes to his revised cosmology. He also adds volumes of other details to flesh out the narrative of LQ1. Yet he leaves the question of transmission untouched. Ironically, Christopher Tolkien refused to consider the revised Myths Transformed cosmology in making the published Silmarllion but stripped Pengolodh from the story on the strength of the purported revision to a Mortal tradition found also in Myths Transformed.

I find the opposite. Tolkien may have stated a desire to change the mode of transmission, but he didn't actually do much to effect this, even when he had the chance to make surface changes to the text that would have set him on the path to deeper revisions. Therefore, I conclude that the "Quenta Silmarillion" should be read as a text written by an Eldarin loremaster and from an Eldarin point of view, with all that entails.

#silmarillion#tolkien#historiography in middle-earth#pengolodh#narrator of the silmarillion#history of middle-earth#myths transformed#statute of finwe and miriel#laws and customs among the eldar#quenta silmarillion#later quenta silmarillion

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the fic name thingy: A Drop Of Liquid Sunshine

okay i’m gonna try and get back into doing these, so if you’re new (hello!), these are synopses of fics that i would write based on the titles people sent to me. and with this one, literally the only thing i can think of is felix felicis, so this could only really be a harry potter au.

so. harry’s a sixth year ravenclaw hell bent on creating potions to cure – not just ease – muggle diseases and cancers. he’s muggleborn, and the moment he learned about magic and found out that he had that power in him, he wondered why everyone didn’t just, y’know, use it to help others. he gets the whole statute of secrecy thing (because he read the whole thing as an eleven-year-old), but he doesn’t understand how anyone could see the suffering of others (magic or muggle or anything in between) and be okay with it.

he’s been locked out of the common room for arguing with the door knocker about her logic again (she said that the answer to “what flies without wings?” was time which, yeah, harry gets that, but also he learned a spell in his very first charms class ever that proves that clever bit of wordplay wrong so, because wingardium leviosa is a thing that exists, everything has the potential to fly without wings and if she can’t accept that then fine) and so he’s down in the library, compiling texts from the restricted section about early wizard-muggle relations before the statute of secrecy was adopted. he opens the first one, sees a graphic illustration of a witch being burned at the stake, flips to another page and sees a muggle being burned at the stake instead, and closes it, realizing why the books were there in the restricted section in the first place.

for a while, he just sits there, his head against the pile of deeply disturbing books, considering going back up to the tower and apologizing to the door knocker. it’s not her fault he was in a bad mood, he’s just stalled on the progress of his potion to cure heart disease and can’t move forward until he figures out how his latest attempt reacts to niffler hair, which just went on the ministry’s restricted materials list and is now impossible to get ahold of.

suddenly, someone takes a seat across from him.

“hi,” says the someone. he props his feet up next to harry’s pile of books. “you look a bit distressed there, mate. thought i could help.”

harry looks up, and his heart beats weirdly against his ribs. louis tomlinson, seventh year, slytherin. eyes that look like the frost on the great lake in the winter, a grin that looks like snow on the castle turrets. harry swallows.

“not distressed, no,” he replies. “stuck.”

“stuck on what?”

“niffler hair.”

“well,” says tomlinson, the corners of his mouth twitching downward as if to say, yeah, that’s a bit shit. “sorry to hear that.”

harry assumes he’s taking the piss; most people like harry, and he has more friends than he knows what to do with sometimes, but they don’t really get his potions… thing. or, at least, the non-ravenclaws don’t get it. the ravenclaws understand hyper-focusing on one specific interest, but they don’t understand the fascination with helping muggles. so, basically, harry doesn’t talk about his potions issues much, and he assumes this is another one of those times he’ll politely end the conversation before it starts.

“thank you,” he says, though, because he’s polite. he stands and starts to gather the books full of burning people to stack them back on the shelf.

“it’s a class IV non-tradable now, isn’t it?” tomlinson says, and harry lays the books back down. “what with nifflers being endangered.”

“yeah,” harry says, slightly agog. “yeah, that’s- that’s my issue.”

tomlinson hums. “that is a tough one.” he scratches a hand through shiny-messy hair. “can get it for you, though. if you’d like.”

harry sits, his legs gone to jelly. “you can?”

tomlinson’s grin turns sharp. “sure.” then, “for something in return.”

so they strike a deal; tomlinson bet his friend (fellow slytherin niall horan, chaser for the quidditch team, all around Everyone’s Best Friend and future hogwarts gamekeeper) that he could successfully brew liquid luck before tomlinson’s birthday in december. unfortunately…

“potions is, sort of, well…” tomlinson trails off. “a weak spot, you could say.”

“a weak spot,” harry repeats.

“yeah, mate. i’m training to be a wandmaker, i’m not even in NEWT-level potions. can barely brew a sleeping draught, let alone felix felicis,” tomlinson admits.

“but you bet that you could make one of the hardest potions possible,” harry says blankly. “even though you aren’t good at potions.”

tomlinson grins embarrassedly. “right, well. that’s why i have you, yeah? i asked around, and everyone said you were the best.”

harry flushes. “well. yeah, sorta.”

tomlinson claps his hands together, and is immediately shushed by madame pince. he doesn’t seem to notice. “excellent.”

so it’s a deal: harry will help him make his liquid luck, and louis will get him his niffler hair. they shake hands, and make plans to meet up in the potions dungeon the following night.

“wait, tomlinson,” harry calls in a whisper before tomlinson leaves.

“call me louis,” he grins, then nods for harry to go on. harry’s heart thumps like a hiccup got stuck in his throat, painful and sharp.

“louis,” harry tries out. “what do you need felix felicis for?”

louis just grins wider, nods again, and walks away.

so they start. they spend a week gathering ingredients and setting up in the dungeon, in the corner where harry usually leaves his long-term potions brewing. they juice squill bulbs and chop up thyme, measure exact perfect portions to store away in case they have to start over and try again. they spend the first hogsmeade weekend together a few weeks after that, shopping for occamy eggs and grabbing a drink at the three broomsticks to celebrate when they find some.

their first attempt goes horribly, terribly wrong, with far too much horseradish making the mixture curdle up and smoke. louis, who’d been the one heavy-handed with the horseradish in the first place, smiles apologetically and clears the cauldron with a flick of his wrist.

“sorry,” he says bashfully. “like i said, rubbish at potions.”

“right,” harry says. “well. time to start over, i suppose.”

so they do. the second attempt goes better; harry’s hand shakes as he squeezes out just a drop of squill bulb juice, but then a drop of his sweat rolls off his nose and into the cauldron, ruining that attempt too. by then it’s october, and he and louis are no closer to a finished batch of felix.

so they’ll try once more.

it’s a long process, if only because they run out of occamy eggs after the second attempt and miranda at Herbs and Tinctures in hogsmeade was told they’d been backordered and it would be a few weeks before they got more. so, instead, harry goes back to work on his own potion; or, more accurately, to stare at his unfinished potion which is also very much stalled. louis thinks it’s funny to sit and watch harry gaze forlornly into his two cauldrons of unfinished potion, so he starts to bring his homework down into the dungeon to make up for all the time he and harry spend together. sometimes louis’ friend niall joins them, his exuberance filling the dungeon, and sometimes harry’s friend liam, a gryffindor prefect who is terrified harry will blow himself up with a bad potion one day, checks in from time to time as well, but mostly it’s just harry and louis left to their own devices.

suddenly, it’s november and they haven’t worked on a potion (either one) in weeks, but it’s okay. louis asks all sorts of questions about harry’s potions and their uses – “wait, muggles can get sick from what? and you fixed it? how?” – and is in awe at harry’s latest attempt.

“’m pureblood, meself,” he says. “can’t imagine getting sick and healers – no, wait, what do muggles call them? doc-something. doctors! – saying that there might be no way for them to help.”

“that’s what i want to fix!” harry says, and louis lets him rant about the state of muggle healthcare for hours, until his stomach growls loudly and he asks harry to accompany him to dinner, where he snags a seat next to harry at the ravenclaw table, takes a bite of pasty, and gestures for harry to continue.

louis gets his chance to do the same, though; harry asks him about wandmaking once and it’s like opening the floodgates – louis’ eyes are always a bit unnaturally sparkly, but when he describes the different phoenix breeds and the strengths each of their tail feathers adds to wands, it’s like seeing a new star in the sky for the first time. harry’s heart does that hiccup again, the one that feels like an impedimenta straight to the sternum.

the occamy eggs arrive in november, less than a month before louis has to have the potion done, and they arrive at exactly the same time as –

“you niffler hair!” louis announces grandly, bounding up to harry in the entrance hall and handing him a small vial of coarse black animal hair.

“where did you get it?” harry gasps, clutching the vial to his chest.

“got a mate named stan,” louis grins. “he can get anything, for anyone.”

harry’s torn; he itches to go try his potion with the new ingredient, but he also has to uphold his end of the bargain, and finish louis’ felix felicis potion. louis, like he can read harry’s thoughts, shakes his head good-naturedly.

“go on,” he laughs. “we can make felix any old time. i have a good feeling about our next attempt. c’mon, i want to see how your potion reacts.”

so they escape to the dungeon, and harry painstakingly adds three tiny hairs to his mixture, then holds his breath and waits. then, just like he’d hypothesized, the potion turns from clear green to cloudy, pearlescent blue.

“it’s done,” harry breathes, and louis claps him on the back as he takes it in, his newest creation.

“you did it,” louis says, and harry suddenly wonders how he was able to ever create a potion before he had louis with him to celebrate at the end.

so all that’s left is the felix felicis, but harry finds himself putting it off when louis suggests they give it a try. he knows it’s because the moment the liquid luck is done, he’ll have no excuse to see louis anymore, but he also hates disappointing louis by telling him “can’t right now, have a defense essay. next week?”

so he finally says yes, and they start the process. ashwinder egg and horseradish, squill bib juice and murtlap algae. louis watches with bated breath over harry’s shoulder and hands over each ingredient at the perfect time, until all that’s left is the powdered rue and to do a bit of stirring.

“you should do it,” harry says when all the ingredients are in the cauldron, bubbling away.

louis takes out his want, waves it once, and says a shaky, “felixempra!”

the potion, which had been clear and smelling profusely of cedar needles, goes thick and molten immediately, shiny gold and filling the room with bright light.

“we did it!” louis whispers, then, yelling, jumps into harry’s arms. “WE DID IT!”

they spin around for a bit, lit by the golden glow from the tiny cauldron full of luck, then harry lets louis back down to gather up his supply. it’s only a small pot, so when louis carefully fills one vial, there’s only about another two portions left. louis doesn’t stopper it, instead holding it up to eye level.

“are you going to tell me what it’s for, now?” harry murmurs, watching louis watch the gold swirling behind the glass.

“nah,” louis says, then lifts the vial to his lips. “i’ll show you instead.”

louis’ throat glows as he swallows, the potion disappearing. louis suddenly looks elated, eyes blue-gold and alight, and he drops the vial perfectly on the edge of the table instead of letting it drop and bust on the floor. he approaches harry slowly, like his limbs aren’t his own.

“what are you doing,” harry mumbles, awestruck.

“i needed all the luck in the world,” louis answers, putting a small, warm hand on the back of harry’s neck, “just for this.”

when he kisses harry, he tastes like apples and honey and smells like rowan trees and cotton; it’s perfect, utterly perfect, mind-blowingly perfect. harry’s mind goes white, overwhelmed as his heart tries to thump its way out of his chest.

when they pull apart, louis’ eyes are dancing. “so it works,” he whispers. “you kissed me back, i must be the luckiest guy in the world.”

“you didn’t need a potion to kiss me,” harry says breathlessly.

“well, drat,” louis says, sounding giddy. “suppose we didn’t need to go to all this trouble after all.”

harry’s mind is still fuzzy from the taste of honey, but it clicks, and he laughs. “there was no bet.”

“oh, there was a bet,” louis says, leaning in again. “niall bet me i’d chicken out before i kissed you.”

“why would you bet that?” harry murmurs against louis’ lips.

“because i’ve loved you for ages, and we’d never even spoken.”

later, niall arrives back at the slytherin seventh years’ dorm and finds a tiny, glowing bottle of golden potion resting in the middle of his pillow. it’s got a ribbon tied around it, a note dangling from the end.

thanks. xx it reads, then at the bottom, all the love. h.

niall grins, then, for the first time, notices that the hangings around louis’ bed are shut tight, but there’s a familiar stack of potion books on the floor next to louis’ bedside table. he chuckles quietly to himself, pockets the little vial of potion, and leaves harry and louis to have their own little bit of luck.

#harryswar#rachel talks#after i'd already written this i found a site that said it has to be brewed for six months#so just take this as my lack of research and pretend it can be done in an afternoon#sorry lol#fic synopsis#drabbles

118 notes

·

View notes