#also just shows how other black people aid in our erasure

Text

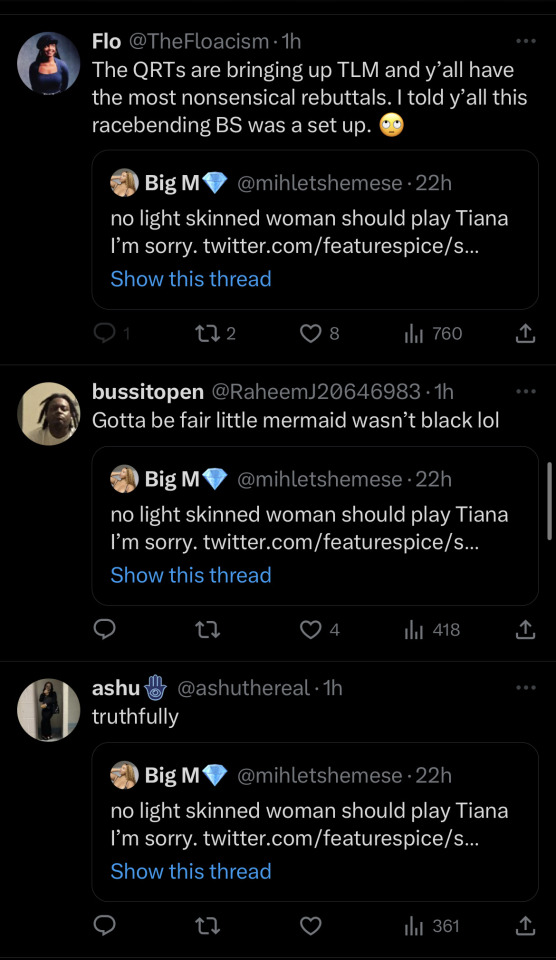

Presented with little to no commentary:

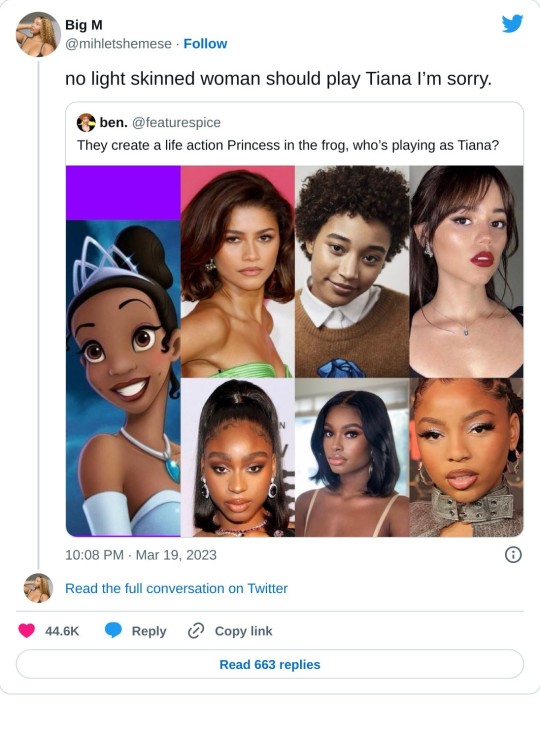

Notice how the original tweeter(who’s a notorious figure who also went by the name of summertimeflo) put light skins, brown skins, a biracial, and a non-Black latina to play Tiana despite Tiana being DARKSKINNED and BLACK!

The only one qualified to play Tiana would probably be Coco Jones who I believe is pictured on the middle bottom.

@thisismisogynoir

#we should’ve known the Ariel casting was a set up for the live action princess and the frog#princess and the frog#princess Tiana#colorism#darkskinned black girl representation#racism#summertimeflo/ben#also just shows how other black people aid in our erasure

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preventing Movements from Being Overlooked in the Age of Activism

Contemporary social movements have a higher chance of fading into the background now more than ever. Benjamin Sáenz, a professor at the University of Texas at El Paso, says “There is no [Chicano] movement per se. That doesn’t mean there is nothing happening” (Guerrero, 61). This holds true for many modern-day movements where people have the Internet to aid in spreading information faster than traditional methods. It’s easy to be forgotten when activists can be branded far-left SJWs (social justice warriors) as a tactic to ignore the message. The racists that many of today’s movements are fighting against can have entire pages taken down after false reports of hate speech. In a country founded on the beliefs of the white, Christian majority we often see the issues that stick are what these people are in direct opposition with – black vs white, gay vs straight, rich vs poor, Christian vs savage. Movements like Black Lives Matter see huge success because they are right – there’s an issue that needs to be addressed – but also because this country thrives on the continued white against black narrative that raises white inhabitants higher on their pedestals. While all social movements of the future have to worry about whether the public regards their goals as positive or negative, it is especially the movements of smaller groups that are vulnerable to being left behind. In addition to the fading of news that inevitably happens with a 24-hour global news cycle, active erasure now occurs with a few clicks.

Because I am not Black, Mexican, or Asian it isn’t my place to speak on the movements of those groups beyond observations of them. I can, however, speak to the many movements of my people. Okla Chahta ohoyo hapia hoke. I am a proud woman from the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. All through school I had teachers ask me if I knew that Native Americans made up just 1-2% of the entire United States population. It was hurtful to always be stared at as if I belonged in some sort of museum, and pushed me to look deeper into the needs of Indian Country as a whole. Issues my tribe doesn’t face, others do; and where there is trouble, there is generally a movement to change the cause for a better outcome. Since the very first colony settled on these lands in 1492, Indigenous peoples have been at risk for becoming one of these aforementioned forgotten groups.

Diminishing the power of those who make up today’s 566+ federally recognized tribes was the goal from day one and that’s obvious when you look at our numbers in the broad population. Even so, this has not stopped the fires burning among us. Every day we fight for a different facet of the erasure and oppression we face: Standing Rock, Bears Ears, Mauna Kea, Native mascots, tribal sovereignty, missing and murdered Indigenous women. The goal is to start these movements and prevent them from disappearing before anything can be accomplished. But how can we ensure that when even movements like that of Colin Kaepernick – who had the attention and support of millions of football fans – can be warped and forced out of the spotlight?

Journalist Jacqueline Keeler, of Navajo and Dakota decent, spoke briefly with me on the issue of staying relevant and being heard. Much of her beliefs appear to lie in the idea that our strength manifests in numbers.

I think that it’s not going to be easy and this is not the natural course of things. The exertion of sovereignty [and] something which I really advocate for: an Indigenous tribal government. I think that we need to organize politically because we’re talking about political rights, you know? Our safety, our security, our identity is only going to be protected politically. All of this is permeable as long as we are not politically strong, so we need to strengthen ourselves politically. Obviously we are talking about several hundred different nations, but we are stronger together and we have more at stake in common than we do apart.

Strengthening ourselves politically is an important idea to consider because tribal sovereignty is already ignored in day to day life. We need leaders who aren’t afraid to assert their power, and from there we need to work together to get our best into the U.S. government. Politics are at a turning point where things will either improve for those experiencing injustice or history will repeat itself.

National headlines detailing Standing Rock Reservation and the protection of sacred sites that were desecrated for the Dakota Access Pipeline proves that this idea of strength in unification is on the right track. Standing Rock is shared by Yanktonai Dakota, Hunkpapa Lakota, and Sihasapa Lakota. People from these tribes united and rallied for help in protecting their lands and burial grounds that were being threatened. Tribe after tribe sent letters of support and representatives to aid in the work that was happening up north. I sent packages of supplies to the very first wave of protectors in April 2016 while urging my tribal leaders to pen their support and send help. I observed Linda Black Elk, of the Standing Rock Sioux, use her background in Ethnobotany as an EMT for the protectors. I watched as needed roles were filled and veterans showed up to stand on the front lines following Trump’s executive order that reversed Obama’s protections. Although the pipeline has been completed, the events at Standing Rock are an inspiring example of strength in numbers. If we can come together and turn the public’s attention to the injustices we face, we can come together and work from inside the corrupt system that holds us down.

A Lakota youth advocate, Megan Red Shirt-Shaw, has worked admissions at multiple universities and is using her experience to work on a project designed to connect Natives pursuing their Ph.D. with mentors in their desired field. This came to mind when reading about Sáenz and Guerrero discussing how “Many of the young leaders of yesterday went to school and are now our doctors, lawyers, educators, and writers” (Guerrero, 61). If wielding our collective power to change societal tradition is key to the social movements of the future, avenues to and participation in academia is necessary. Education will be the foot in the door for minorities in politics; without which nothing will change about the lack of diversity in our representatives. The statistics for politicians in the United States proves that the diversity of the country is not reflected. In 2015 I read a Washington Post article titled “The new Congress is 80 percent white, 80 percent male and 92 percent Christian” that went on to detail the exact numbers of the 114th Congress. This country is not in a crisis where our population of women is severely lacking in numbers, so why is it that our government doesn’t more accurately reflect the diversity of the current population? Activism taking center stage in conversations across these lands means more youth are likely to actively pursue higher education and get involved in politics. As these numbers rise there is higher potential for the government to accurately represent this nation’s inhabitants.

By working together toward the ultimate power of representation we will eventually be able to reinvent the foundation of this country without a radical anarchy. And that’s how it should be done – slowly and with enough thought that everyone can benefit – otherwise we run the risk of someone being left out or these lands being damaged further. “Critics will rightly contend that co-management is not an ideal status for tribes. We are indigenous to the land and by right should have complete authority. But the political reality is that we don’t” (Curley, 72). I don’t believe there is a need to speak of something as severe as overthrowing and abolishing the government while minorities are at such a clear disadvantage. Though a nice fantasy to dwell in, a slow trickle into spaces that don’t currently have their doors open to us will be much easier.

While it is less than ideal to have to work so much harder than those currently in power just for the chance to enter their stadium, it’s worth it when we look at the cause. The root of any social movement examined corresponds with lack of power and that’s why we must focus on taking back said power and distributing it where deserved. Without that we will only see movements grow silent and fade out like the Chicano movement and the water protectors at Standing Rock. Movements visible to those who are involved, but otherwise unseen. We can choose to let the media pit us against other movements, break us from the inside, and turn onlookers against us or we can cease to feed that monster and focus on feeding ourselves. The majority will look away when comfortable and it is in those moments that we can choose to stay down where they want us or build up.

Works Cited

Bump, Phillip. “The New Congress is 80 Percent White, 80 Percent Male, and 92 Percent Christian.” Washington Post. 5 January 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the- fix/wp/2015/01/05/the-new-congress-is-80-percent-white-80-percent-male-and-92- percent-christian. January 2017.

Curley, Andrew. “Some Thoughts on a Long-Term Strategy for Bears Ears.” In Edge of Morning: Native Voices Speak for the Bears Ears, (pp. 66-73). Jacqueline Keeler. Salt Lake City, Utah: Torrey House Press. May 2017.

Guerrero, Salvador. “The Chicano Movement – Alive and Evolving.” In English One Reader, (pp. 61-62). Charles Brown. (Original work published 2011)

PROMPT: to be added. Blog & posts under construction/revision.

#paper two: social movements#grade: excellent#native american#college#english one#essay#personal#cultural#september 2018

1 note

·

View note

Text

Another Queer Bites the Dust at This Year’s Golden Globes

Awards Season!

If you’re like me, you’re probably suffering right now with an existential quandary, somehow caught in the space between knowing that award shows do not matter in the scope of things and only represent the Hollywood establishment which is only a tiny portion of the arts and being glued to your TV set to see who wins best picture this year.

And if you’re also like me, by which I mean queer (or care about queer stuff), you were probably pretty psyched for this awards season. The Favourite, The Green Book (not to be confused with The Green Mile), Bohemian Rhapsody, Can You Ever Forgive Me?, Boy Erased, Rafiki, Colette, Lady Gaga’s existence, and more . . . there have been so many queer films to come out (heh) in 20gayteen.

At the Golden Globes this past weekend we saw an array of queer films nominated, and, I’ll be honest, I was pumped. It looked like it would be a great year for representation.

But then.

So without further ado, here’s the piping hot dish of queer erasure casserole that was the 2019 Golden Globes, folks.

Thought this year was a success for queers everywhere after the Golden Globes? Well, in point of fact . . . nope. Despite wins by The Green Book, Bohemian Rhapsody, The Favourite, and The Assassination of Gianni Versace, which all told queer stories, this year’s Golden Globes failed queer audiences massively.

Let’s break it down.

1. The Green Book? More like The Story Book.

The Green Book is a film that tells the story of Dr. Don Shirley, an insanely talented black pianist, and his white driver, Tony Vallelonga as they travel through the deep South on tour. Shirley, who happens to be a queer black man, and Vallelonga, despite their early differences (like Vallelonga’s being super racist), navigate issues of race and class throughout their journey and eventually end up as friends and comrades.

Sounds great. Except.

First off, the movie was adapted and directed by Nick Vallelonga, the son of Shirley’s driver, who wrote the book that The Green Book was adapted from. In other words, it was the white man’s version. The film has come under constant fire since its public debut from none other than Shirley’s family, particularly his brother. Mhmm. Bad news.

Next, the trailers released for the film and other promotional materials don’t even nod to the scenes in the film in which it is revealed that Shirley’s oppression is criss-crossed with his identity as a queer black man. True, the preview shown during the Golden Globes ceremony did include a clip that revealed the pianist’s identity, sandwiched between shots of Vallelonga beating up people who were attempting to assault him.

All in all, the movie smacks not only of queer erasure, but an elixir for white guilt. We as white people love to eat up feel good stories about white people who reach across culture and race boundaries to form “color-blind” relationships built on true empathy and compassion (see The Help, Shawshank Redemption, Hidden Figures). Stories that often take place, (coincidentally?) in the 1960s at the height of segregation. Which is funny, because it perpetuates the idea that race issues are all resolved now, as a result of the compassion shown by white people to black folks Way Back When. As anybody who’s got a sense of what’s going on in the world—or their own backyards—that’s far from the case.

Just sayin’.

2. The Assassination of Gianni Versace: Or, Another Straight Gets a Golden Globe for Playing a Gay and Everyone Eats it Up.

Ah, Darren Criss. This isn’t the first time we’ve been down this road. Have we.

It started with Glee. Criss played Blaine, opposite Chris Colfer’s Kurt Hummel, an adorable baby gay with an impossibly effeminate singing voice that was ear candy if I’ve ever heard it. Criss, of course, very talented too. I lived for their relationship as boyfriends on the show, and tried to suck it up and pretend not to be disappointed when I found out that Criss (somehow???) was not queer in real life.

Then there was Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and now, Gianni, in which he plays the famed designer’s killer, Andrew Cunanan. All gays. All roles he was praised the hell out of for performing. He even won a GG for best actor in a limited series last Sunday.

And sure, Criss recently stated in a Bustle interview that he will no longer play gay characters so as not to be “another straight boy taking a gay man’s role” as the actor said.

That’s all fine and good, but that article was published in December. And at the GG’s this year? No mention of it in his acceptance speech. At all. If it weren’t already too little, too late for the guy, that last snub certainly makes it so.

I mean, I sort of forgive him for Glee though.

And finally. The worst offender of them all.

3. Bohemian Rhapsody, But, Like, Without the Part Where Freddie Mercury Dies from AIDS.

This one pains me. I don’t want to admit it happened. But it did. And it was REAL bad.

Rami Malek. Even as a lesbian, I love him. Okay, I said it. He’s a cutie, and he’s extremely talented (See Mr. Robot), and his voice sounds like how coffee would taste (I imagine) if I liked coffee. And when I saw the first trailers for Bohemian Rhapsody, I was PUMPED. Thank God they got an actual person of color to play Freddie Mercury who, most people don’t even know, was also a person of color (yeah, his name was Farrokh Bulsara). The likeness, too, was pretty impeccable.

Freddie Mercury was one of the most famous bisexuals of his time, rivaled only by David Bowie, perhaps, who together produced perhaps the greatest and gayest moment that rock music ever saw when they collaborated on “Under Pressure.” Malek, always an enigma, I’m not going to jump to conclusions about his sexuality since he’s never stated it publicly, but, let’s just say he’s only ever dated women.

Which is all fine and good on its own.

But Bohemian Rhapsody had already come under scrutiny for “straight-washing” after the release of its first trailer, which completely masked Mercury’s queerness, quickly followed up by another trailer that gave audiences a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it dose. As an article featured on Into stated regarding that sprinkle of queerness, “It’s the kind of passable moment that straight audiences wouldn’t take offense at and gay viewers could feel like they had some semblance of representation.”

Needless to say, we were off to a rough start.

So while I was watching the Golden Globes, watching Rami Malek walk on stage and accept his Best Actor award, of course I was nearly praying in my head that Malek would mention Mercury’s queerness. That would have made things better for disappointed queers. And honestly, Mercury’s memory deserved it, along with all the others who had their lives cut short during the AIDS epidemic.

So what brilliant lines had he to say about that? Nothing. Not a mention of AIDS or Mercury’s queerness was uttered by Malek or the production team who accepted the GG for best Drama.

Frankly, I wish I could say I was surprised. Or enraged. Or something. But as the 2019 Golden Globes ceremony came to a close half an hour late, I just had a kind of half grimace on my face.

As my mom would say about every fashion choice I made in high school: Disappointed, but not surprised.

It was looking like it was going to be a good year for queers during award season, but we’re really not starting off on a great foot. Yet, I should add, we queers and allies should take courage, and tell ourselves that it’s not over until the last white guy receives an Oscar. Our fates are not yet writ. With a little over six weeks left, we have two options.

First, for those of you who are staying tuned in, have hope. There are a lot of queer films, TV shows, and artists in the running at this year’s award shows. The Golden’s are pretty indicative of how the Oscars turn out, but they’re not a direct reflection. And there’s still time for people, (Ahem, Rami Malek and Darren Criss) to do justice to the queer community as potential allies.

Second, for those of you who don’t care about awards shows, take pride in knowing that you’re probably right. It probably doesn’t matter. Nothing really matters, after all . . . ♫

#lgbtq community#lgbt writers#awards season#golden globes#bohemian rhapsody#film#queer films#queer culture#the green book#american crime story

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Anti-Defamation League publishes an annual report on incidents of anti-Semitism in the United States. This year’s audit, made available in November, showed a significant increase in relation to the previous year: 2017 saw a 67% rise in anti-Jewish hate speech, harassment, vandalism, and violence.

It’s a disheartening measure of a terrible phenomenon. Yet in the three months since the audit was released, it’s garnered little attention.

...Underlying this is a pervasive point of view is the notion that Jews, who are often conflated with whites, should “check their privilege,” because anti-Semitism just isn’t as bad as other forms of racism. On campus, where the ADL notes an acute rise in anti-Jewish hostility, alarmed Jewish students are sidelined for being white and middle-class and the Holocaust is trivialized as “white on white crime”. Elsewhere, Jews who protest anti-Semitism are dismissed for failing to ante up sufficient concern about people of color.

This erasure of anti-Semitism isn’t simply callous. It exposes a huge moral failure at the heart of the modern Left. Under the enveloping paradigm of “intersectionality,” everyone is granularly defined by their various identities — everyone, that is, except white Jews, whose Jewishness is often overwritten by their skin color. Not simply a moral failing, this erasure is deeply hazardous, inasmuch as the fight against racism happens by and large in sectors where the Left perspective dominates — the academy, pop culture, and much of the news media.

...For in a key sense, regular racism, against blacks and Latinos for example, is the opposite of anti-Semitism. While both ultimately derive from xenophobia, regular racism comes from white people believing they are superior to people of color. But the hatred of Jews stems from the belief that Jews are a cabal with supernatural powers, in other words, it stems from the models of thought that produce conspiracy theories. Where the white racist regards blacks as inferior, the anti-Semite imagines that Jews have preternatural power to afflict humankind.

This is also why the Left is blind to Anti-Semitism. Anti-Semitism differs from most forms of racism in that it purports to “punch up” against a secret society of oppressors, which has the side effect of making it easy to disguise as a politics of emancipation. If Jews have power, then punching up at Jews is a form of speaking truth to power — a form of speech of which the Left is currently enamored.

...At its most trivial, a conspiracy theory is the idea that a circumstance or event can be explained by the influence of an evil secret society. As the historian Norman Cohn has shown, European civilization has embraced this idea since the beginning. The “fantasy,” writes Cohn, “that there existed somewhere in the midst of the great society, another society, small and clandestine, which not only threatened the existence of the great society, but was also addicted to practices which were felt to be wholly abominable, in the literal sense of anti-human,” has targeted different groups — the Jews, in particular — ever since Christianity conquered Europe.

...But the idea at the center of the long history of Jewish persecution is a conspiracy theory: that a wicked cabal of international Jews conspires to leech from and destroy mankind.

...As they were emancipated, Jews loomed as direct competition in economic and political life. As the preeminent historian of anti-Semitism, Robert Wistrich, writes, “Alongside the dominant cultural matrix of late-nineteenth-century nationalism, volkisch racism, and imperialism,” a new “populist social dimension” recast Jews as collaborators with the secular demons of laissez-faire capitalism and liberal democracy.

Thus, as the center of civilization shifted from Church and King to the nation state, anti-Semitism, at least outwardly, lost its religious focus. Foes of the Jews who aspired to power cast them as diabolical puppeteers who controlled the state; anti-Semites in power libeled them as seditious parasites who undermined it. This was the milieu that produced the foundational document of political conspiracism, “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion”.

Purporting to be the minutes of an international meeting of evil Jewish elites, “The Protocols” was a detailed outline of how the Jews would enslave and exploit humankind. First circulated in the Russian empire, it was then exported by charlatans and military officers and spread throughout the world. Effectively the first “fake news”, the pamphlet, which Cohn memorably called a “warrant for genocide”, still flourishes today, especially in Arab and Muslim countries.

While it is a quintessentially modern document, “The Protocols” owes a clear debt to medieval thought. Murder, greed, warmongering, enslavement, false consciousness, opposition to the truth, and betrayal of the good are all explicit in the work.

...The Nazis furnish the best testament to the lethal power of this sinister little book. Look how indebted to it Joseph Goebbels revealed them to be:

“Jewry has so deeply infected the Anglo-Saxon states both spiritually and politically that they are no longer have the ability to see or accept the danger. It conceals itself as Bolshevism in the Soviet Union, and plutocratic-capitalism in the Anglo-Saxon states. The Jewish race has always been an expert at mimicry, that is, the systematic ability to fade into its surroundings. We know that from our own past. They put their host peoples to sleep, they drug them, paralyzing their ability to defend themselves against the life-threatening danger from Jewry.”

...Today’s conspiracist blends the mindset of the medieval magician with the viciousness of the inquisitor. The old fears about crop-fouling and well-poisoning, for example, are now directed at GMOs and fluoride in the water. The idea that doctors and sorcerers were one and the same surfaces in paranoia about AIDS and vaccines. And flat-earthers rehearse astrological debates about the cosmos.

But the Jews remain a primary target.

And it’s anti-Semitism’s source in conspiracy theory that renders it so different from non-conspiracist forms of racism, like anti-blackness.

As with most racism, antiblack bias constructs an underclass to be exploited or avoided. It positions blacks as inferior to whites and charges them with stereotypes that signal weakness: They are libeled as lazy, stupid, lustful, criminal, and animalistic.

The conspiracy theory of anti-Semitism turns this on its head. The Jew becomes a magical creature: Brilliant, cunning, greedy, stealthy, wealthy, and powerful beyond measure. Anti-Semitism imagines a diabolic overclass to be exposed and resisted.

...Above all else, anti-Semitism is a conspiracy theory about the maleficent Jewish elite. And it’s this that makes it easy to disguise as a politics of liberation, or at least, to embed anti-Semitism quietly in efforts for social justice.

...It’s critical to note that Americans are not accustomed to recognizing, let alone understanding, a sizable portion of anti-Semitism, because it typically doesn’t resemble antiblackness — the horrific down-punching form of racism that haunts American history and reverberates into the present.

But this blindness doesn’t just make space for anti-Semites to operate domestically; it occludes our sense of the history of other parts of the world (do you remember the concept of conspiracy theory coming up during your education on the Holocaust? Me neither).

...In the spring of 2016, the Stanford University Student Senate debated a resolution, undertaken in light of strident activism on campus against Israel, to condemn anti-Semitism, citing conspiracy theories about “the power of Jews as a collective—especially but not exclusively, the myth about… Jews controlling the media, economy, government or other societal institutions.”

A student senator named Gabriel Knight objected that the resolution would “irresponsibly” stifle what he thought was a “very valid discussion.” He admonished that “Questioning these potential power dynamics… is not anti-Semitism.”

A week ago, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas delivered a rant of over two hours to assemble Palestinian leaders. He alleged wild conspiracies, raving in what would have been news to Anne Frank that “[The Western powers] wanted to bring Jews here from Europe to maintain European interests in the region. They asked Holland, which had the largest navy in the world, to transfer the Jews.”

...Neither of these episodes would have been likely if we primarily understood anti-Semitism as a conspiracy theory. If he had recognized anti-Semitism as a paranoid religion that offers vulgar salvation to the oppressed, Gabriel Knight might not have insisted on interrogating the privilege of Jews. If J Street’s leaders [who publicly decried Abbas’ comments] knew the classic tropes of conspiracism, they would have heard in Abbas’ drug-dealing canard and Holocaust denial echoes of something too big to be laid at the feet of an American politician — two thousand European years of fanatical dualism, feudal fatalism, superstition, fear, and cleansing violence.

Americans are — thankfully — tuned to detect and deplore racism that punches down. But we must broaden our perspective if we want to reverse the progress of anti-Semitism, which punches up toward mass murder and extermination.

So when the ADL reports that incidents of anti-Semitism rose by 67% in 2017, view it in this light. That’s what it means when white supremacists march and shout, “Jews will not replace us!” This form of hatred thrives in conditions where demagogues undermine the institutions of liberal democracy.

We live in a time of hateful rhapsody where truth is relative and fear prevails.

This is a conspiracist moment and it’s bad for the Jews.

Read John-Paul Pagano’s full piece at the Forward.

#everyone should really read the full piece#it's everything i've been screaming for years#John Paul Pagano#antisemitism#Conspiracy Theories#long post#forward

939 notes

·

View notes

Photo

How Gentrification Is Criminalizing New York City’s Subway Dancers

Gentrification is shifting the culture of MTA’s underground performance ecosystem, particularly for African American and Hispanic youth. Police are finding a means of controlling what can’t be taxed and removing an art form misunderstood, but present since the 1980s. There’s a fourth wall that exist between Showtime performers, passengers riding the train and the police. There’s a language of survival that exist within the Showtime community that’s misinterpreted. Unfortunately, it is written off as a crime. Showtime has a way of commanding attention. It’s a form of hip-hop. Meanwhile, New York newbies have deemed it disruptive and unsafe.

As an alternative, programs such as Showtime NYC and Music Undergroundare zoning Showtime performance to places like Battery Park and Union Square. Police are advised to handout slips to performers with information about where they can, rather than arresting them. Ainsely Brundage, a former Showtime performer, said, “It’s micromanaged and structured in a way that puts limitations on dancers and performers in general.”

He started performing at the age of 14 and stopped in 2014. During his stint he was arrested 14 times and experienced all manner of rudeness from subway passengers, from being called the n-word to being tripped. It was never about a childhood hobby when Brundage started dancing on the train, it was about making money for food. The criminalization of the Showtime performance over the last couple of years has caused an erasure of a job market, while redefining what is permissible and impermissible when it comes to performance on the MTA. While Brundage was trying to make ends meet by dancing, he was also trying to figure out what freedom of expression meant apart from his home.

One of the most vivid examples of having his freedom of expression policed at home was when his father cut off his locs.

“I came to the realization that my last exhale was when I had locs. The moment that my stepfather forced me to the barbershop, forced the barber to cut my hair because he thought that was the reason I was getting in trouble and misbehaving in school. Ever since then I feel like I’ve never been the same. Over the years I’ve made attempts to grow my hair back, because I feel like that was my way of trying to reconnect to that feeling of actually being free,” Brundage said.

A policed state is something he’s had to work with his entire life. So for Brundage these “organized” efforts of controlling Showtime performance are seen as yet another attempt to police. “These programs are great and all. Zoned performances and all, that’s great. But we need to decriminalize it. Because while they are doing zoned performances people are still being arrested for performing on the train. And I think that’s wrong.”

Brundage is only 22, but his resilient response to life is a fully formed testimony. A Midtown pizzeria is where we first met. Without many introductory questions, he immediately began to share his life’s story. He opens up about his tremulous relationship with his family, being kicked out of his home and going from homeless to becoming an acting student all within a year’s time.

Originally from Bushwick, Brooklyn, he was raised in a West Indian household by his stepfather and mother. During his time living at home, he chronicles how his parents wouldn’t feed him. His stepfather even went so far as to lock food away.

Showtime was his meal ticket. He learned by getting on the train at 2 and 3 a.m. when the carts were empty and trying out routines.

Most Showtime performers have a team they do routines with, but for the most part Brundage was a one-man show. He said, he wanted to make as much money as possible by doing it alone. On a good week he could easily make between $800 and $1000 dollars, which he used to attend his first year of school at Brooklyn College.

During his time as a solo Showtime performer he met Malcolm Fraser. “We both just met each other through hard times. That’s how we just started dancing on the train together. I have a hat, you have a radio, let’s make this money together,” Fraser said.

Ainsley’s performance name was Top Star, which he has tattooed on his forearm. “That’s what he considered himself to be a ‘top star’,” Fraser said. Fraser went by Richie Rich after his uncle’s name. Fraser began dancing on the train when he was 15.

The two formed a brotherly bond, Fraser only a year older than Brundage would teach him various moves. And then just like that it all came to an end for the two in 2015, they found new jobs where there wasn’t a constant risk of being arrested.

Fraser is originally from the Brownsville, Brooklyn, and is still teaching. We spoke for the first time over the phone, where he began to share his stories of encountering the police and effects of gentrification as a Showtime performer. “They complain about these kids who are just trying to make money for food, or find a way out. Nobody likes looking at the dirty train. And you complain about these kids dancing. That’s what gentrification does. The culture is hustle.”

Fraser has an international audience and dances on above ground platforms. He’s traveled everywhere from London to China showing others the techniques of litefeet dancing. However, both Brundage and Fraser noted that they would never go back to Showtime performing.

“I would rather put myself in a performance light, where people come to you. It’s kind of a degrading feeling. It’s kind of embarrassing. That’s not everyone’s take on it. You learned out of necessity, because there was no other way for me to eat,” Fraser said.

Today, they are using their craft in a different light. They’ve even had the opportunity to star in an Intel commercial together.

vimeo

“I like to give people an outlet to express themselves. I don’t have a set place that I teach right now. I have people who are willing to fly me overseas. I have a set job in London and I’ve taught in China,” Fraser said.

He hopes to one day own a lot of land and have a lot of arts programs. “People are really connected to the arts in some sort of way. I think if the arts caught us at an earlier age, and killed our ego it would really change things,” Fraser said. Brundage’s plans for the future include attending the Mason Gross School of the Arts for acting. There are plenty of other narratives similar to Fraser and Brundage’s.

Black and Hispanic youth in the city deserve spaces where they can make money while exercising their freedom of expression, ones that aren’t policed. Showtime is not meant to be polite and this where it’s unfortunate relationship with law enforcement stems from.

Like Brundage, Fraser his experienced getting ticketed and arrested during his time as a Showtime performer. “I danced really clean. I try not to kick anyone. They just saw that I had speakers on me. They knew that I had just finished dancing. That’s the only reason they ticketed me,” Fraser said. Eventually, the $100 ticket Fraser received was dropped. He noted that it all started because they finally realized how much untaxed money these kids were making. “They move to New York for the culture and then call the cops on the culture,” Fraser said.

“People who don’t understand, people come here and romanticize our struggles. They turn it into something for profit, that’s what is happening,” Fraser said.

Subway performances like violin, guitar and piano playing are engaged with like a harmless backdrop.

One Organization’s Fear of Gentrifying Subway Performance Culture

Matthew Christian is the founder of Busk NY, an organization that believes in a New York where public performance is a vibrant and celebrated part of artistic life. Christian, originally from Vermont, started the organization three years ago after moving to New York and choosing to play his guitar on the subway platform as a hobby.

“There wasn’t a whole lot of opportunity to perform and one of my favorite things was the larger town near mine had a festival where they would gather on Main Street and a local business invited my brother and I to play, and that was my favorite thing. So when I came to the city after college, I learned that performance was allowed in the subway, so I went out for the first time in 2011 and the second day I went out I was wrongfully arrested and that was sort of my introduction,” Christian said.

Back in 2013, Christian was arrested for playing his guitar on the subway platform. Since then, his organization has built a community around performers who have had similar experiences. We first met near Grand Central on 42nd Street, where he began to discuss the community that Busk NY has formed since its inception.

Christian said he believes Busk NY is potentially aiding in the work of gentrifying subway performance culture. Busk NY is faced with the challenge of making sure their work is reflective of and advocating for the diversity of subway performers and not just another white faced organization unconsciously becoming a fresh face for subway performances. Instead, organizations such as Busk NY have to do the work of breaking through the cultural barriers that exist between Showtime performing just trying to make a living and those playing an instrument on the subway platform as a hobby.

“It’s not common in the city to see young black men or Hispanic men get a chance to perform, so it’s really powerful particularly as a high school teacher to see them in that space,” Christian said.

Showtime Diagnosed With Broken Windows Policing

Former New York Police Commissioner William Bratton diagnosed Showtime performance in the MTA with Broken Windows Policing.

In theory Broken Windows Policing was implemented to prevent “disruptive” anti-social behavior and vandalism. Introduced in 1982 by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling, it was an extension of “Stop and Frisk” and became just another excuse to troll and terrorize Showtime performers to the point of largely putting an end to it on the MTA.

The rise of gentrification is rewriting the rules of what can and can’t be done in public spaces based off preconceived ideas of what is a potential “threat.” As neighborhood demographics change and longtime residents are priced out, it’s important that we consider gentrifications many repercussions on marginalized communities of color.

These laws were written without prior knowledge of the people, their language or economy that came before it. These days Showtime performances are pretty scarce. It’s a treat if you get to experience it even once a month during your daily commute on the MTA.

youtube

#gentrification#white people#racism#showtime nyc#showtime#music underground#ainsely brundage#priscilla ward#battery park#union square#mtz#transportation#mass transit authority#new york city#william bratton#broken windows#broken windows policing#james q. wilson#james q wilson#george l. kelling#george l kelling#stop and frisk#malcolm fraser#dance#black dance#black culture#matthew christian#busk ny#us policing#police state

1 note

·

View note

Link

Soraya Roberts | Longreads | March 2020 | 10 minutes (2,569 words)

“Can I talk to you in private?” No one wants to hear those words. The impulse is to assume you’ve done something egregiously wrong. The expectation is that you are about to be punished. The conviction is so strong that the only good thing about it is that, at least initially, you can suffer without anyone else knowing about it. You might even thank the punisher for coming to you directly, for keeping it between just the two of you. It’s the least someone can do when they are about to theoretically ruin your life.

A lot has been written about privacy online, in terms of information, in terms of being policed. Ecuador is currently rushing to pass a data protection law after a breach affected as many as 20 million people — more than the country’s population. A lot has also been written about callout and cancel culture, about people being targeted and cast off (if only temporarily), their entire history dredged up and subjected to ex post facto judgement; Caroline Flack, the British television presenter who recently committed suicide while being hounded in the press and online amid allegations she had assaulted her on-again, off-again boyfriend, was seen as its latest casualty. But there hasn’t been a lot of talk about the hazier in-between, about interpersonal privacy online, about missteps once dealt with confidentially by a friend or a colleague or a boss, about the discrete errors we make that teach equally discrete lessons so as not to be repeated in public. That’s not how it is anymore, not in a world tied together by social media. Paper trails aren’t just emails anymore; they take in any move you make online, most notably on social media, and the entire internet is your peevish HR rep. We’re all primed — and able — to admonish institutions and individuals: “Because of social media, marginalized people like myself can express ourselves in a way that was not possible before,” Sarah Hagi wrote in Time last year. “That means racist, sexist, and bigoted behavior or remarks don’t fly like they used to.”

Which is to say that a lot of white people are fucking up, as usual, but now everyone, including white people and people of color, are publicly vilifying them for it as tech’s unicorn herders cash in on the eternal flames. And it’s even worse than in the scarlet letter days: the more attention the worse the punishment, and humiliation online has the capacity for infinite reach. As Sarah John tweeted after one particular incident that left a person hospitalized, “No one knows how to handle cancel culture versus accountability.”

* * *

“Is that blood?” That was my first question after a friend of mine sent me a message with a link to a few tweets by a person I’d never heard of, the editor-in-chief of a small site. The majority of the site’s staff had just resigned, the impetus being a semi-viral tweet, since deleted, of a DM the editor had sent a Twitter chat in 2016: “I was gonna reply to this with ‘nigga say what?’ Then I was like holy shite that’s racist, I can’t say that on twitter.” According to Robert Daniels at the Balder and Dash blog on rogerebert.com, tweeters, mostly white, piled on — some even called the EIC’s workplace demanding they be fired — before the office-wide resignation. Videos embedded in the tweets I saw showed the editor crying through an apology. (Longreads contacted the editor for comment; they’ve asked to remain anonymous for their health and safety.)

Initially I thought the videos were just a mea culpa, but then I saw a flash of red. Though the details are muddied by a scrubbed social media history, the editor appeared to have harmed themselves. Ex-colleagues rushed to their aid, however, and they were eventually hospitalized. If that wasn’t horrible enough, a filmmaker named Jason Lei Howden decided to avenge the EIC. With scant information, apparently, he targeted individuals on Twitter who weren’t involved in the initial pile-on, specifically blaming two people of color for the crisis — Valerie Complex and Dark Sky Lady, who had not in fact bullied anyone but had blogged about Howden. The official Twitter account of Howden’s new film, Guns Akimbo, got mixed up in the targeted attacks, threatening the release of the film.

There are multiple levels to this that I don’t understand. First, why that DM was released; why didn’t the person simply confront the EIC directly? Second, why did the editor’s staff, people who knew them personally, each issue individual public statements about their resignations into an already-growing pile-on? (I don’t so much wonder about the pile-on itself because I know about the online disinhibition effect, about how the less you know a person online, the more you are willing to destroy them.) Third, why the hell did that filmmaker get involved, and without any information? Why did the white man with all the clout attack a nebulous entity he called “woke twitter” — presumably code for “people of color” — and point a finger at specific individuals while also denying their response to one of the most inflammatory words in the English language (didn’t they realize it was an “ironic joke,” he scoffed)? As Daniels wrote, “This became a cycle of blindspots, and a constant blockage of discussing race, suicide, and alliance.” Why, at no point, did anyone stop to think about the actual people involved, about maybe taking this private, to a place where everything wasn’t telegraphed and distorted?

Paper trails aren’t just emails anymore; they take in any move you make online, most notably on social media, and the entire internet is your peevish HR rep.

I had the same question after the BFI/Thirst Aid Kit controversy. In mid-February, the British Film Institute officially announced the monthlong film series THIRST: Female Desire on Screen, curated by film critic Christina Newland and timed to coincide with the release of her first book, She Found It at the Movies (full disclosure: I was asked to participate, but my pitch was not accepted). The promotional image included an illustration of a woman biting her lip, artwork similar to that of three-year-old podcast Thirst Aid Kit (TAK), a show that covers the intersection of pop culture and thirst. Newland later told The Guardian she wondered about the “optics,” but as a freelancer with no say on the final design, she deferred to the BFI. She had in fact twice approached TAK cohost Nichole Perkins to contribute to her book (the podcast’s other cohost is Bim Adewunmi). Perkins told me in an email that she wanted to, but her work load eventually prevented her. And while TAK did share the book’s preorder link, the BFI ultimately failed to include the podcasters in the film series as speakers, or even just as shout-outs in the publicity notes — doubly odd, given that Adewunmi is London-based. Quote-tweeting the BFI’s announcement and tagging both the institute and Newland, TAK responded, “Wow! This sounds great. Hope our invitation arrives soon!”

The predictable result was a Newland pile-on in which she was accused of erasing black women’s work, followed by a TAK pile-on — though Perkins told me her personal account was “full of support and kindness” — for claiming ownership over a term that preceded them. All three women ended up taking time away from Twitter (which is a sacrifice for journalists whose audience depends on social media) though Newland has since returned. I asked Perkins if she had thought about dealing with the situation privately at first. “I did consider reaching out to Christina before quote-tweeting, yes,” she wrote. “I wonder if she considered reaching out to us, especially after she saw the artwork for the season and admittedly noticed ‘something going on with the optics,’ as she is quoted as saying in The Guardian.” Eventually, the BFI contacted Perkins and Adewunmi and released a statement apologizing “for their erasure from the conversation we are hoping to create from this season” and announcing a change of imagery. They also noted that Newland, as a guest programmer, was not responsible for their marketing mistake, though no reason was given for their omission. “I have no idea why the BFI or Ms Newland didn’t include Thirst Aid Kit in the literature about the Thirst season,” Adewunmi wrote to me. “I was glad, however, to see the institution acknowledge that initial erasure, as well as issue an apology, in their released statement.”

At around the same time, a similar situation was unravelling in the food industry. Rage Baking: The Transformative Power of Flour, Fury, and Women’s Voices, an anthology edited by former Food Network VP Katherine Alford and NPR’s Kathy Gunst, was published in early February. The collection of more than 50 recipes and essays presents baking as “a way to defend, resist, and protest” and was supposedly inspired by the 2016 election. The hashtag #ragebaking was used to promote the book on social media in January, which brought it to the attention of a woman named Tangerine Jones, whose Instagram followers believed the idea had been stolen from her and alerted her — and the rest of the world. Unprompted by Jones, Alford and Gunst DM’d her to say they had learned the term elsewhere and that the book was “a celebration of this movement.” Jones called them out publicly, publishing their DMs in a Medium essay entitled “The Privilege of Rage,” in which she described how she came up with the concept of rage baking — using the #ragebaking hashtag and the ragebaking.com URL — five years ago, as an outlet for racial injustice. “In my kitchen, I was reminded that I wasn’t powerless in the face of f**kery,” she wrote. Jones’s supporters started a pile-on, her article shared by big names like Rebecca Traister, who had contributed to the collection and requested that her contribution be removed from future editions.

In an abrupt turn of events, the Jones advocates were promptly confronted with advocates of the book, who redirected the pile-on back at Jones for kicking up a fuss. “It is beyond f**ked up that my questioning the authors’ intentions and actions is being framed as detrimental to the success of other black women,” she tweeted. Their silence resounding, the Simon and Schuster imprint ultimately issued a statement that failed to acknowledge their mistake and instead proposed “in the spirit of communal activism” to include Jones in subsequent printings. Unappeased, the baker called out the “apology” she received privately from Alford and Gunst, who told her they were donating a portion of the proceeds to the causes she included in her post (though their public apology didn’t mention that), and asked if she would be interviewed as part of the reprint. “Throwing black women under the bus is part of White Feminist legacy,” Jones tweeted. “That is not the legacy I stand in, nor will I step in that trap.”

Kickstart your weekend reading by getting the week’s best Longreads delivered to your inbox every Friday afternoon.

Sign up

According to Lisa Nakamura, a University of Michigan professor who studies digital media, race, and intersectionality, cancel culture comes from trying to wrest control in a context in which there is little. It’s almost become a running joke the way Twitter protects right-wing zealots while everyone else gets pummeled by them. It follows then that marginalized populations, the worst hit, would attempt to use the platform to reclaim the power they have so often been denied. But as much as social media may sometimes seem like the only place to claim accountability, it is also the worst place to do it. In a Medium post following their Howden hounding, Dark Sky Lady argued that calling out is not bullying, which is true — but the effects on Twitter are often the same. “The goal of bullying is to destroy,” they wrote. “The goal of calling out and criticizing is to improve.” Online, there appears to be no improvement without destruction in every direction, including the destruction of those seeking change. On one end, a group of white people — the EIC, Newland, Alford, Gunst — was destroyed professionally for erring; on the other were the POC — Perkins, Adewunmi, Jones — who were personally destroyed, whose pain was minimized, whose sympathy was expected when they got none. The anger was undoubtedly justified. Less justified was the lack of responsibility for how it was deployed — publicly, disproportionately, with countless people’s hurt revisited on specific individuals, all at once.

We know how pile-ons work now; it’s no defense to claim good intentions (or lack of bad intentions). There were few gains for either side in any of these cases, with the biggest going to the social media machine that feeds on public shame and provides no solution, gorging on the pain of everyone involved without actually providing constructive way forward, creating an ever-renewing cycle of suffering. A former intern for the ousted EIC tweeted that she understood the impulse to critique cancel culture and support the editor, but noted that “there is something sad about the fact that my boss used a racial slur, and I am not allowed to criticize.”

* * *

So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed author Jon Ronson told Maclean’s in 2015 that one of his biggest fears is being defined by one mistake, and that a number of journalists had basically told him, “I live in terror.” I am no exception. Just recently I experienced a comparatively tame callout on Twitter, and even that moderate critique made me drop an entire book project, wonder about a job opportunity that subsequently dissolved, and second-guess every story idea I’ve had since. The situation was somewhat helpful in making me a more considerate person but was exponentially more helpful in making me anxious and in inspiring hateful fantasies about people I had never met. I am 100 percent certain that the first gain would have been made just as successfully had people spoken to me privately and would have saved me from the second part becoming so extreme that I had to leave social media to recalibrate. The overwhelming sense I’m left with is that if I say something that someone doesn’t like, even something justifiable, my detractors will counter with disproportionate force to make whatever point it is they want to make about an issue that’s larger than just me. What kind of discourse is that which mutes from the start, which turns every disagreement into a fight to the death, which provides no opportunity for anyone to learn from their failures? How do we progress with no space to do it?

“I think we need to remember democracy. When somebody transgresses in a democracy, other people give them their points of view, they tell them what they’ve done wrong, there’s a debate, people listen to each other. That’s how democracy should be,” Ronson told Vox five years ago. “Whereas, on social media, it’s not a democracy. Everybody’s agreeing with each other and approving each other, and then, if somebody transgresses, we disproportionately punish them. We tear them apart, and we don’t want to listen to them.” The payment for us is huge — almost as big as the payout for the tech bros who feign impartiality when their priority is clearly capital and nothing else. This is a punitive environment in which we are treating one another like dogs, shoving each other’s noses into the messes we have made. Offline, people are not defined by the errors they make, but by the changes they make when they are confronted with those errors, a kind of long game that contradicts the very definition of Twitter or Facebook or Instagram. The irony of public shaming on social media is that social media itself is the only thing that deserves it.

* * *

Soraya Roberts is a culture columnist at Longreads.

0 notes

Link

CarlosDavid.orgOn June 28th, 1969, the Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village became a major catalyst in the movement for LGBTQ rights. Transgender activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera were among the boldest and most outspoken leaders who stood up against the ongoing police brutality and harassment that plagued the now landmark gay bar for months. Wilson Cruz on Stonewall 50: ‘I Am Inspired by All the LGBTQ People of Color Who Ignited the Revolution’The actions that occurred that night at Stonewall weren’t a protest, but a riot—violent, disruptive, and purposely resistant. The LGBTQ community had enough of the state-sanctioned discrimination and abuse. Blood was shed, fighting ensued, arrests were made—the police were not there to protect and serve, but to persecute and torture. Johnson, who was celebrating her 25th birthday that night, was the first to resist, followed by Rivera who threw one of the first bottles at the oppressive police. The revolution sent shockwaves across the nation as many other cities began to stand up and fight back against LGBTQ inequality. Fifty years later, we owe our current progress to these two fearless black and brown transgender women who risked their lives in the fight for LGBTQ liberation. Today, we have marriage equality, a gay candidate running for president, mainstream media representation, and Congress just recently pushing to pass the Equality Act—a law that would extend civil rights and protections to all LGBTQ Americans nationwide. On Thursday, NYC Police Commissioner James P. O'Neill made an unprecedented apology on behalf of the Police Department for the conduct of the officers during Stonewall. “The actions taken by NYPD were wrong—plain and simple,” O'Neill said during a Pride event at police headquarters. His remarks were a long overdue apology for a major gross abuse of police force.Despite the diverse leadership it initially took for the movement to advance, many of the achievements since have benefited the most privileged within our community: white cisgender gay men. Browse through any disparity study on LGBTQ people, and black members of the community are often hit the hardest. Despite the public awareness of these setbacks, black and brown queer people continue to be underrepresented in LGBTQ leadership, media, and visibility. LGBT pioneer Sylvia Rivera leads an ACT-UP march past New York's Union Square Park, June 26, 1994.Justin Sutcliffe/APAnd while many had hoped for racial harmony within the LGBTQ community, I’ve learned first-hand that we still have a long way to go. As the former LGBTQ editor for Philadelphia magazine, I’ve spent the past three years covering racial discrimination in our own rainbow flag-waving backyard. From gay bar owners insulting black patrons with racial slurs, to white-led LGBTQ nonprofits being protested against by diverse community members, I’ve come to recognize that the fight for diversity and inclusion is not just happening outside of the LGBTQ community, but within it. But this is nothing new. History has already shown us that black queer and transgender people have always had to remind the rest of the community of our prominence—despite the fact that the movement was co-led by us since the beginning. While many people rightfully praise the late gay political icon Harvey Milk, our community doesn’t give as much respect to civil rights legend Bayard Rustin. Rustin, a black gay activist who openly embraced both his identities at a time when they were being federally marginalized, took on some tough battles. Throughout the 1940s until his death in 1987, Rustin was a steadfast revolutionary who was intersectional and strategic. He led the effort to get the historic 1963 March on Washington off the ground and advocated for equal legal protections for LGBTQ people before it was popular. “The only final security for all is to provide equal protection for every group under the law,” Rustin said while testifying before the General Welfare Committee of New York City Council in 1986.But Rustin was only one of several black LGBTQ activists who were ahead of their time. The Combahee River Collective Statement, formulated by a group of black queer women in 1974, was a groundbreaking manifesto that reshaped the way we now discuss feminism and intersectionality.Co-founded by acclaimed black lesbian activist Barbara Smith, the Combahee River Collective gave a voice to black queer women at a time when they were excluded from mainstream movements. Some of the intersectional values expressed by this trailblazing group can be seen in many movements today, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, whose founding leadership include black queer women.Such activism wasn’t just projected in policy and direct action, but through pop culture. The legendary James Baldwin and Alice Walker weren’t the only black queer writers who spoke truth to power—the 1986 anthology In the Life, edited by Joseph Beam, also redefined how we saw ourselves as well. At 27 years old, it never really dawned on me how much black queer culture has been highly consumed by society at large until I watched the groundbreaking 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning which spotlighted the immersive and deep history of New York City’s black queer ballroom drag scene. While many now freely use the colloquial phrases “throwing shade,” “read you for filth,” and “spill the tea,” it was impoverished black queer and transgender drag performers who originated those terms decades ago while facing a HIV/AIDS epidemic that still hasn’t gotten better for people like them. Fast-forward to now, and we’re still talking about the ballroom scene’s impact through the new hit show Pose on FX that includes a remarkable amount of diverse LGBTQ actors, writers, producers, and directors. Films such as the Oscar-winning film Moonlight, books such as Charles Blow’s Fire Shut Up In My Bones, and the rise of black LGBTQ voices from public figures such as Billy Porter, Lena Waithe, Roxane Gay, Janet Mock, Janelle Monáe, Laverne Cox, Sharron Cooks, Raquel Willis, Tre’vell Anderson, Don Lemon, and other countless activists and entertainers, give me hope. But again, we still have a long way to go. Right now, LGBTQ progress is being threatened under the presidency of Donald Trump. We have already witnessed ongoing federal setbacks to policies impacting the transgender community and those living with HIV. The unaddressed racial pitfalls that have unfairly crippled black and brown LGBTQ people have made matters worse in the very safe spaces we should be considering home.It hurts to see the lack of diversity and the erasure of black queer and transgender revolutionaries during Pride month, and to see companies that still lack our visibility in their offices take up space in our parades. Pride wouldn’t exist without the work of black and brown LGBTQ activists who risked their lives and reputations on behalf of a community that haven’t paid their proper respects. As we move into the next 50 years, let’s not continue to ignore and silence the accomplishments of black and brown LGBTQ community members. Give them a seat at the table and a mic at the podium. Pay them in equity and access, not tokenization and exploitation. It can’t be a true Pride celebration until we are all free. This is what Marsha P. Johnson would have wanted because she once said so herself: “As long as gay people don’t have their rights all across America, there’s no reason for celebration.”This Pride season, it’s time to put the rainbow flags and cocktails down and put our fists back up. The revolution is still not over; there’s plenty of work to be done.Read more at The Daily Beast.Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines https://yhoo.it/2I3KyQG

0 notes

Link

CarlosDavid.orgOn June 28th, 1969, the Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village became a major catalyst in the movement for LGBTQ rights. Transgender activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera were among the boldest and most outspoken leaders who stood up against the ongoing police brutality and harassment that plagued the now landmark gay bar for months. Wilson Cruz on Stonewall 50: ‘I Am Inspired by All the LGBTQ People of Color Who Ignited the Revolution’The actions that occurred that night at Stonewall weren’t a protest, but a riot—violent, disruptive, and purposely resistant. The LGBTQ community had enough of the state-sanctioned discrimination and abuse. Blood was shed, fighting ensued, arrests were made—the police were not there to protect and serve, but to persecute and torture. Johnson, who was celebrating her 25th birthday that night, was the first to resist, followed by Rivera who threw one of the first bottles at the oppressive police. The revolution sent shockwaves across the nation as many other cities began to stand up and fight back against LGBTQ inequality. Fifty years later, we owe our current progress to these two fearless black and brown transgender women who risked their lives in the fight for LGBTQ liberation. Today, we have marriage equality, a gay candidate running for president, mainstream media representation, and Congress just recently pushing to pass the Equality Act—a law that would extend civil rights and protections to all LGBTQ Americans nationwide. On Thursday, NYC Police Commissioner James P. O'Neill made an unprecedented apology on behalf of the Police Department for the conduct of the officers during Stonewall. “The actions taken by NYPD were wrong—plain and simple,” O'Neill said during a Pride event at police headquarters. His remarks were a long overdue apology for a major gross abuse of police force.Despite the diverse leadership it initially took for the movement to advance, many of the achievements since have benefited the most privileged within our community: white cisgender gay men. Browse through any disparity study on LGBTQ people, and black members of the community are often hit the hardest. Despite the public awareness of these setbacks, black and brown queer people continue to be underrepresented in LGBTQ leadership, media, and visibility. LGBT pioneer Sylvia Rivera leads an ACT-UP march past New York's Union Square Park, June 26, 1994.Justin Sutcliffe/APAnd while many had hoped for racial harmony within the LGBTQ community, I’ve learned first-hand that we still have a long way to go. As the former LGBTQ editor for Philadelphia magazine, I’ve spent the past three years covering racial discrimination in our own rainbow flag-waving backyard. From gay bar owners insulting black patrons with racial slurs, to white-led LGBTQ nonprofits being protested against by diverse community members, I’ve come to recognize that the fight for diversity and inclusion is not just happening outside of the LGBTQ community, but within it. But this is nothing new. History has already shown us that black queer and transgender people have always had to remind the rest of the community of our prominence—despite the fact that the movement was co-led by us since the beginning. While many people rightfully praise the late gay political icon Harvey Milk, our community doesn’t give as much respect to civil rights legend Bayard Rustin. Rustin, a black gay activist who openly embraced both his identities at a time when they were being federally marginalized, took on some tough battles. Throughout the 1940s until his death in 1987, Rustin was a steadfast revolutionary who was intersectional and strategic. He led the effort to get the historic 1963 March on Washington off the ground and advocated for equal legal protections for LGBTQ people before it was popular. “The only final security for all is to provide equal protection for every group under the law,” Rustin said while testifying before the General Welfare Committee of New York City Council in 1986.But Rustin was only one of several black LGBTQ activists who were ahead of their time. The Combahee River Collective Statement, formulated by a group of black queer women in 1974, was a groundbreaking manifesto that reshaped the way we now discuss feminism and intersectionality.Co-founded by acclaimed black lesbian activist Barbara Smith, the Combahee River Collective gave a voice to black queer women at a time when they were excluded from mainstream movements. Some of the intersectional values expressed by this trailblazing group can be seen in many movements today, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, whose founding leadership include black queer women.Such activism wasn’t just projected in policy and direct action, but through pop culture. The legendary James Baldwin and Alice Walker weren’t the only black queer writers who spoke truth to power—the 1986 anthology In the Life, edited by Joseph Beam, also redefined how we saw ourselves as well. At 27 years old, it never really dawned on me how much black queer culture has been highly consumed by society at large until I watched the groundbreaking 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning which spotlighted the immersive and deep history of New York City’s black queer ballroom drag scene. While many now freely use the colloquial phrases “throwing shade,” “read you for filth,” and “spill the tea,” it was impoverished black queer and transgender drag performers who originated those terms decades ago while facing a HIV/AIDS epidemic that still hasn’t gotten better for people like them. Fast-forward to now, and we’re still talking about the ballroom scene’s impact through the new hit show Pose on FX that includes a remarkable amount of diverse LGBTQ actors, writers, producers, and directors. Films such as the Oscar-winning film Moonlight, books such as Charles Blow’s Fire Shut Up In My Bones, and the rise of black LGBTQ voices from public figures such as Billy Porter, Lena Waithe, Roxane Gay, Janet Mock, Janelle Monáe, Laverne Cox, Sharron Cooks, Raquel Willis, Tre’vell Anderson, Don Lemon, and other countless activists and entertainers, give me hope. But again, we still have a long way to go. Right now, LGBTQ progress is being threatened under the presidency of Donald Trump. We have already witnessed ongoing federal setbacks to policies impacting the transgender community and those living with HIV. The unaddressed racial pitfalls that have unfairly crippled black and brown LGBTQ people have made matters worse in the very safe spaces we should be considering home.It hurts to see the lack of diversity and the erasure of black queer and transgender revolutionaries during Pride month, and to see companies that still lack our visibility in their offices take up space in our parades. Pride wouldn’t exist without the work of black and brown LGBTQ activists who risked their lives and reputations on behalf of a community that haven’t paid their proper respects. As we move into the next 50 years, let’s not continue to ignore and silence the accomplishments of black and brown LGBTQ community members. Give them a seat at the table and a mic at the podium. Pay them in equity and access, not tokenization and exploitation. It can’t be a true Pride celebration until we are all free. This is what Marsha P. Johnson would have wanted because she once said so herself: “As long as gay people don’t have their rights all across America, there’s no reason for celebration.”This Pride season, it’s time to put the rainbow flags and cocktails down and put our fists back up. The revolution is still not over; there’s plenty of work to be done.Read more at The Daily Beast.Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines https://yhoo.it/2I3KyQG

0 notes

Link