#aluminium mesh

Text

Why Epoxy Coated Mesh rules over Aluminium Mesh

When it comes to choosing between epoxy mesh and aluminum mesh for fly screens, there are a few factors to consider. Here are some reasons why epoxy mesh is often considered better than aluminum mesh:

Durability: Epoxy mesh is generally more durable and long-lasting compared to aluminum mesh. It is resistant to corrosion, rust, and weathering, making it suitable for outdoor applications. On the other hand, aluminum mesh can be susceptible to corrosion over time, especially in humid or coastal environments.

Strength and Tear Resistance: Epoxy mesh tends to be stronger and more tear-resistant than aluminum mesh. It can withstand greater impacts and is less likely to get damaged by accidental pushing, pulling, or pets clawing at it. Aluminum mesh, while still relatively strong, may be more prone to denting or puncturing.

Insect Protection: Both epoxy coated mesh and aluminum mesh are effective at keeping insects and pests out of your living spaces. However, epoxy mesh often has smaller mesh openings, which can provide better protection against tiny insects like mosquitoes and gnats. Aluminum mesh may have larger openings that could potentially allow smaller insects to pass through.

Maintenance and Cleaning: Epoxy mesh is generally easier to clean and maintain compared to aluminum mesh. It can be easily washed with mild soap and water without worrying about corrosion or damage. Aluminum mesh may require more frequent cleaning and occasional maintenance to prevent corrosion and keep it looking its best.

Aesthetics: Epoxy mesh offers a sleek and unobtrusive appearance, blending well with different architectural styles and window frames. It is available in various colors and finishes to match your home's aesthetics. Aluminum mesh, while still visually appealing, may have a more noticeable metallic look that might not suit every design preference.

Allergies and Sensitivities: Some people may have allergies or sensitivities to aluminum, particularly when it comes in contact with their skin. Epoxy mesh does not pose the same risk and is generally considered hypoallergenic.

It's worth noting that both epoxy mesh and aluminum mesh have their own advantages and can be suitable for different situations.

Read more about why epoxy mesh for fly screen here.

#epoxy coated mesh#epoxy mesh#epoxy wire mesh#aluminium mesh#aluminium wire mesh#aluminium fly screen#mosquito net

0 notes

Photo

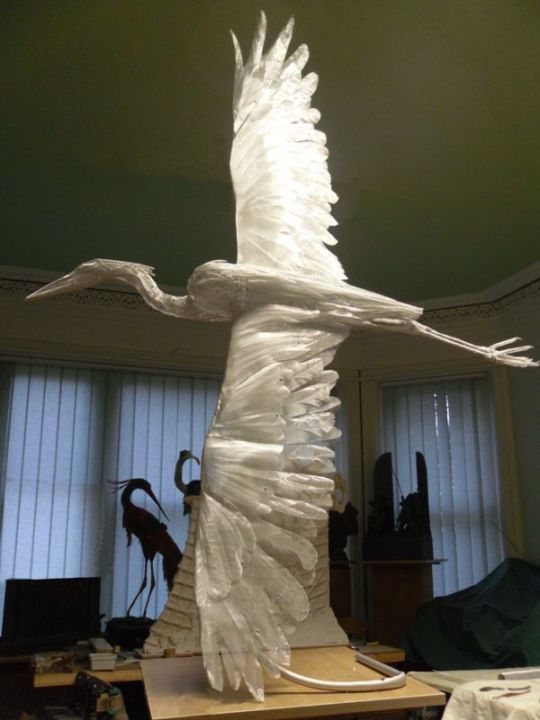

A sculpture titled 'Flying Egret (Lifesize Bird Garden Pond Hanging statue)' by sculptor Kenneth Potts. In a medium of Aluminium Tube, Mesh Sheeting and in an edition of 1/1.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

aluminium mesh sheet manufacturer since 2006, offer all types of customized aluminium sheet

0 notes

Text

Aluminium Wire Mesh Manufacturers in Gorakhpur: Dhariwal Industries Sets the Standard for Quality and Performance

When it comes to sourcing reliable and top-quality aluminium wire mesh, look no further than Dhariwal Industries. As one of the leading Aluminium Wire Mesh Manufacturers in Gorakhpur, we have established a reputation for delivering exceptional products that meet the highest industry standards.

At Dhariwal Industries, we understand the importance of durable and versatile wire mesh in various applications. That's why we utilize premium-grade aluminium and cutting-edge manufacturing processes to produce wire mesh that offers outstanding strength, corrosion resistance, and longevity. Our products are designed to withstand the toughest environments and provide reliable performance.

With a diverse range of wire mesh options, we cater to a wide array of industries and applications. Whether you need wire mesh for architectural projects, industrial machinery, filtration systems, or security applications, Dhariwal Industries has the perfect solution. Our extensive product line includes woven mesh, expanded mesh, perforated mesh, and more, all customizable to suit your specific requirements.

One of the key factors that set Dhariwal Industries apart is our unwavering commitment to customer satisfaction. We prioritize understanding our clients' needs and providing them with tailored solutions. Our team of experts works closely with you to ensure that you receive the ideal wire mesh product that meets your project specifications.

When you choose Dhariwal Industries, you can expect not only exceptional products but also unparalleled service. Our efficient production processes and robust quality control measures ensure that you receive your orders on time and in perfect condition. We take pride in our prompt and reliable delivery, allowing you to stay on schedule and complete your projects seamlessly.

Furthermore, our competitive pricing makes Dhariwal Industries the smart choice for aluminium wire mesh. We believe in offering premium quality at affordable rates, ensuring that our customers receive the best value for their investment.

As Aluminium Wire Mesh Manufacturer In Gorakhpur, Dhariwal Industries is dedicated to pushing the boundaries of quality, performance, and customer satisfaction. Experience the difference of working with a trusted industry leader and elevate your projects with our superior wire mesh solutions. Contact Dhariwal Industries today and let us be your partner in success.

#Aluminium Wire Mesh Manufacturers In Gorakhpur#Aluminium E Channel Manufacturers in Thane#Aluminium Jali Manufacturers in Bhubaneswar#Curtain Pipe Manufacturers in Udaipur

1 note

·

View note

Text

Enhancing Pool Safety with Rebar Wire Aus Products Pty Ltd, a Leading Pool Fence Manufacturer in Sydney

Introduction: Swimming pools are wonderful additions to any property, providing a refreshing escape during the hot summer months. However, ensuring the safety of those around the pool is of paramount importance. That's where Rebar Wire Aus Products Pty Ltd, a reputable pool fence manufacturer in Sydney, comes into the picture. With their commitment to excellence and dedication to pool safety, they have become a trusted name in the industry.

Unparalleled Quality and Durability: Rebar Wire Aus Products Pty Ltd takes immense pride in producing high-quality pool fences that meet and exceed industry standards. By utilizing the finest materials and employing skilled craftsmen, they create robust and durable pool fences that offer reliable protection.

Compliance with Regulations: As responsible pool fence manufacturers, Rebar Wire Aus Products Pty Ltd understands the importance of adhering to safety regulations. They ensure that their pool fences are designed and manufactured in accordance with the stringent requirements set forth by local authorities. This ensures that the pool fences not only provide safety but also comply with legal obligations.

Customized Solutions: Every pool has its unique characteristics and design requirements, and Rebar Wire Aus Products Pty Ltd acknowledges this fact. They offer customized pool fences tailored to the specific needs of each customer. Whether it's a residential pool or a commercial water park, their expert team works closely with clients to deliver pool fences that seamlessly integrate with the surroundings while maintaining optimal safety.

Variety of Materials: Rebar Wire Aus Products Pty Ltd provides an extensive range of materials for pool fences, allowing customers to choose the option that best suits their preferences and requirements. From sturdy steel to sleek aluminum, they offer versatile materials that combine strength and aesthetics.

Attention to Detail: When it comes to pool safety, every detail matters. Rebar Wire Aus Products Pty Ltd pays meticulous attention to the construction and installation process, ensuring that every aspect is handled with precision. From the height of the fence to the gap spacing, their pool fences are designed to eliminate potential hazards and provide a secure environment for pool users.

Exceptional Customer Service: Rebar Wire Aus Products Pty Ltd believes in building lasting relationships with their customers. Their friendly and knowledgeable team is always ready to assist clients, providing guidance and support throughout the entire process. From the initial consultation to the final installation, they prioritize customer satisfaction and strive to exceed expectations.

Conclusion: When it comes to pool safety, Rebar Wire Aus Products Pty Ltd stands out as a reliable and reputable pool fence manufacturer in Sydney. With their commitment to producing high-quality, compliant, and customized pool fences, they ensure that swimming pool areas are secure for everyone. By choosing Rebar Wire Aus Products Pty Ltd, you can have peace of mind, knowing that your pool fence is designed and crafted with utmost care and dedication to safety.

#chain wire fencing supplies#chain link fence#gabion walls#Pool Fence Manufacturer Sydney#Metal Fabrication Sydney#358 Mesh#Aluminium Louvres#Aluminium Fabrication Sydney#Steel Fabrication Sydney#Security Fencing Manufacturers

0 notes

Text

Efficient and Eco-Friendly Furnace Solutions by Thermochem Furnaces Pvt Ltd

A furnace is a crucial piece of equipment widely used in various industries for heating materials to high-temperature levels. Thus, choosing a reliable and experienced furnace manufacturer is paramount. In this blog, we will introduce Thermochem Furnaces Pvt Ltd - one of the top furnace manufacturers in India, producing high-quality furnaces designed for diverse industrial applications.

Thermochem Furnaces Pvt Ltd is a reputed company in the field of industrial furnace manufacturing. The company is based in Gujarat and has been offering high-quality furnaces to its clients for over 15 years. With state-of-the-art designs and advanced manufacturing capabilities, Thermochem Furnaces Pvt Ltd is well-equipped to cater to the diverse needs of its clients.

Reliable and Cost-Effective Furnace Solutions

Aluminium Annealing Furnace: The aluminium annealing furnace is designed to anneal aluminium wires, sheets, and other forms of materials. These furnaces use a heating process that eliminates any stresses in the aluminium, making the material more ductile and malleable. Thermochem Furnaces Pvt Ltd provides a range of aluminium annealing furnaces that guarantee high-quality annealing at low operational costs.

Pusher Type Furnace: This is a type of furnace that is useful when heating materials in containers that need to be moved across the furnace's length for heating. Thermochem Furnaces Pvt Ltd has an extensive range of pushertype furnaces, suitable for applications such as steel bars, forgings, and billets.

Roller Hearth Furnace: A roller hearth furnace is utilized to support mass production of small pieces that need to be heated uniformly. The furnace utilizes a conveyor belt that moves products through the furnace's tunnel while heating them uniformly. Thermochem Furnaces Pvt Ltd produces a range of roller hearth furnaces designed for ceramics, glass, and other materials.

#aluminium annealing furnace#pusher type furnace#roller hearth furnace#bogie hearth furnace#mesh belt furnace#log homogenizing furnace#drop bottom furnace

0 notes

Text

Premium Aluminium Windows

We are Fenestration experts. We measure, make and install state-of-the-art aluminium window systems, Mosquito screens, Skylights, Integrated Venetian blinds and insect screen systems.

#Aluminium Windows#Sliding windows#Casement windows#Mosquito Net Screens#Mosquito mesh#insect screens#ALUMINIUM LOUVERS#INTEGRATED VENETIAN BLINDS#Aluminium Doors#CASEMENT DOOR#SLIDING FOLDING DOOR#SKYLIGHTS

1 note

·

View note

Link

0 notes

Text

Homophobia in drag

When I was a young boy, I loved spending the night at my grandmother’s house. There, I could stay up as late as I wanted, and in the morning, there would always be Cinnamon Toast Crunch for breakfast. But the best part was raiding the closet in her basement, which was full of the gowns she had worn in the 1960s and 1970s – frilly pink and purple confections made of lace, chiffon and silk. I would put them on and watch The Golden Girls, sophisticatedly sipping Coke from a wine glass.

When I was nine, my dad bought a video camera, a giant monstrosity that my siblings and I struggled to balance on our shoulders while we filmed home videos. Alone, I’d prop the camera on the coffee table and record myself modelling various outfits, explaining to the camera why this plaid shirt went with these cargo shorts, or why this teal Starter jacket complemented these acid-washed jeans so perfectly. I captured on camera the dance I had painstakingly choreographed to Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch’s ‘Good Vibrations’.

As a kid, I followed my two older sisters around like a shadow, mimicking their mannerisms – the way they tucked loose strands of hair behind their ears when they were concentrating on their maths homework; the way they jutted their hips whenever they were talking to cute boys. Like them, I was a naturally athletic kid. My favourite sport was lacrosse, but I much preferred to play with the girls instead of the boys. The boys were quick to push and shove, and they loved to whack each other with their aluminium sticks. Girls relied more on their speed, their reflexes and the skills they’d honed to keep the ball securely cradled in the shallow mesh of their wooden sticks.

I grew up in a fundamentalist Christian community – most people would call it a cult. From kindergarten to the sixth grade, I attended the community’s tiny school. Because enrollment was so low, there was no in-crowd, no separate cliques of jocks and geeks. In retrospect, I’m sure my classmates and especially my teachers noticed my gender-nonconformity – all of my home videos prove that it was glaring – but it went largely ignored. All that mattered was that we were good Christians, that we loved Jesus and evangelised God’s Word to as many people as possible. When I learned about homosexuals in Bible class, or about AIDS (which we were told God had created to punish homosexuals for their sins), I didn’t think for a moment that I was one of them. Sure, my first real crush, when I was 11, had been on a boy – Elijah Wood, an actor about my age whose performance in the 1994 B-movie, North, had captured my heart. But at the time, before sexual maturity, I mistook the longing I felt for Elijah with the more sanitised desire to simply keep his company and be his best friend. I indiscriminately absorbed all of the lessons I learned about homosexuals, as if they were and would always be irrelevant to my life.

The summer after my sixth-grade year, my family left the community and we moved to a neighbouring town. I began seventh grade in a large public school, where there was definitely an in-crowd. My new classmates wasted little time informing me how unacceptable it was for a boy like me to behave the way I did – the way I enunciated my s-words, the way I brushed my auburn hair, which I had highlighted the previous summer with Sun-In. They called me a faggot, delivered me notes that said everyone knew my ‘dirty little secret’. They asked me frequently, ‘Are you a boy or a girl?’. Well, of course I was a boy, I would respond, trembling.

Meanwhile, I was beginning to sexually mature; I was soon developing crushes that inspired more than just a desire to keep a boy’s company. With horror, I realised that I might actually be what the kids were calling me – which, I knew in my bones, guaranteed me a tragically short life and a one-way ticket to hell. That, after all, was what the old form of homophobia entailed. Self-loathing.

To survive the onslaught, I defeminised myself. I lowered my voice, started wearing baggy jeans and sweatshirts, cut the highlights out of my hair, and replaced my Mariah Carey CDs with Nirvana. Soon, the fear and the anxiety became too much to bear, and the only refuge I found was in alcohol and drugs.

In high school, with each passing year, my drug use got worse. After graduation, I lasted one semester in college before dropping out. Two months later, at the age of 19, I had my first of several stays in a local psychiatric ward. I was delusional, addicted to drugs and suicidal.

It was during my second stay in the psychiatric ward that I was introduced to a 12-step programme, which was how I would eventually get sober in my early twenties. It was slow-going in the beginning of my sobriety to accept my homosexuality. I began to reconnect with the young boy I had once been, the boy whose interests expanded beyond what was typical for males. I experimented with bronzer and mascara, and got French manicures and pedicures.

Engaging in these behaviours felt liberating for a while, but eventually the novelty wore off. In fact, they started to feel performative. I realised I didn’t need those things to be my authentic self. My ideas, my voice, the way I treat other people – these are the things that make me the person I truly am.

In 2011, when I was 28, I fell in love with a man. The following year, I joined the fight for marriage equality. After we won that campaign, I knew I wanted to become a gay activist. I wanted to help create a world in which feminine boys and butch girls could exist peacefully in society. A world in which gender-nonconforming people were accepted as natural variations of their own sex. Minorities, sure, but real and valid nonetheless.

The trans question

In 2017, at the age of 33, I enrolled at Columbia University, New York to complete my undergraduate degree. There, I was shocked to discover how gay activism had evolved since marriage equality became the law of the land. The focus was now entirely on personal pronouns and on being ‘queer’. My classmates labelled me ‘cis’, short for cisgender. I didn’t even know what it meant. All I knew was that they called me ‘cis’ in the same cadence that the seventh graders had called me ‘fag’.

Soon, I learned about nonbinary identities, and that some people – many people – were literally arguing that sex, not gender, was a social construct. I met people who evangelised a denomination of transgenderism that I had never heard of, one that included people who had never been gender dysphoric and who had no desire to medically transition. I met straight people whose ‘trans / nonbinary’ identities seemed to be defined by their haircuts, outfits and inchoate politics. I met straight women with Grindr accounts, and listened to them complain about the ‘transphobic’ gay men who didn’t want to have sex with women.

All around me, it seemed, straight people were spontaneously identifying into my community and then policing our behaviours and customs. I began to think that this broadening of the ‘trans’ and ‘queer’ umbrella was giving a hell of a lot of people a free pass to express their homophobia.

At Columbia, I took classes on LGBT history, but much of that history was delivered through the lens of queer theory. Queer theorists appropriate French philosopher Michel Foucault’s ideas about the power of language in constructing reality. They argue that homosexuality didn’t exist prior to the late 19th century, when the word ‘homosexual’ first appeared in medical discourse. Queer theorists proselytise a liberation that supposedly results from challenging the concepts of empirical reality and ‘normativity’. But their converts instead often end up adrift in a sea of nihilism. Queer theory, which has become the predominant method of discussing and analysing gender and sexuality in universities, seemed to me to be more ideological than truthful.

In my classes on gender and sexuality in the Muslim world, however, I discovered something else, too. I learned about current medical practices in Iran, where gay sex is illegal and punishable by death, and where medical transition is subsidised by the state to ‘cure’ gays and lesbians who, the theocratic elite insists, are ‘normal’ people ‘trapped in the wrong bodies’. I privately drew parallels between the anti-gay laws and practices of Iran and what I saw developing in the West, but I convinced myself I was just being paranoid.

Then, I learned about what was happening to gender-nonconforming kids – that they were being prescribed off-label drugs to halt their natural development, so that they’d have time to decide if they were really transgender. If so, they would then be more successful at passing as the opposite sex in adulthood. Even worse, I learned that these practices were being touted by LGBT-rights organisations as ‘life-saving medical care’.

It felt like I was living in an episode of The Twilight Zone. How long were these kids supposed to remain on the blockers? And what happens in a few years, if they decide they’re not ‘truly trans’ after all, and all of their peers have surpassed them? Are they seriously supposed to commence puberty at 16 or 17 years of age? These questions rattled my brain for months, until I learned the actual statistics: nearly all children who are prescribed puberty blockers go on to receive cross-sex hormones. Blockers don’t give a kid time to think. They solidify him in a trans identity and sentence him to a lifetime of very expensive, experimental medicalisation.

I wondered how different these so-called trans kids were from the little boy I had been. Obviously, I grew up to be a gay man and not a transwoman. But how could gender clinicians tell the difference between a young boy expressing his homosexuality through gender nonconformity, and someone ‘born in the wrong body’? I decided to dig deeper into the real history of medical transition.

Medicalising homosexuality

What I learned validated all of my worst fears. I learned that for decades after their invention, synthetic ‘sex hormones’ were used by doctors and scientists who sought to ‘cure’ homosexuality, and by law enforcement to chemically castrate men convicted of committing homosexual acts.

I learned about actress and singer Christine Jorgensen, one of the first people in the US to become widely known for having ‘sex-reassignment’ surgery in the early 1950s. Jorgensen may now be celebrated by the modern ‘LGBTQIA+’ community as a trans icon, but he seemed more concerned with escaping his homosexuality, which he said was ‘deeply alien to my religious attitudes’. As Jorgensen put it, ‘I identified myself as female and consequently my interests in men were normal’.

I learned that of the first adolescents to be treated for gender dysphoria (or what was then called ‘gender identity disorder’) with puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones in the 1990s and early 2000s, the vast majority were homosexual. And I learned that these studies inform current ‘gender-affirming care’ practices.

Soon, I met detransitioned gay men who had sought an escape from internalised and external homophobia in a transgender identity. They continue to suffer severe post-surgical complications, years after their vaginoplasties.

I began to fear we had reached a point of no return a couple of years ago, during a conversation I had with a supposedly ‘progressive’ friend. I told her that, if I had been a young boy now, I likely would have been prescribed puberty blockers and gone on to medically transition. ‘And you don’t think you would’ve been happy as a transwoman?’, she asked me. Her question left me speechless. I couldn’t find the words to state the obvious: that I am a gay man, not a transwoman; that statistics tell me my medical transition may not have been successful; and that I would suffer severe medical complications. In any case, if I had transitioned, I wouldn’t be living an authentic life. After all, isn’t that what this is supposed to be about? Living authentically?

Sylvester, an androgynous disco icon of the 1970s and 1980s, was once asked what gay liberation meant to him. He answered, ‘I could be the queen that I really was without having a sex change or being on hormones’. Perhaps I belong in an earlier era, when newly liberated gays and lesbians rebelled against the medical and psychiatric experiments they had long been subjected to. Perhaps my early aspiration of expanding what it means to be a boy or a girl was nothing but a pipe dream. In Europe, there is hope that these medical experiments will cease, and that gay and lesbian adolescents will be spared from a lifetime of medicalisation. But in the US, nearly eight years after same-sex marriage became the law of the land, it is full-steam ahead with these homophobic practices.

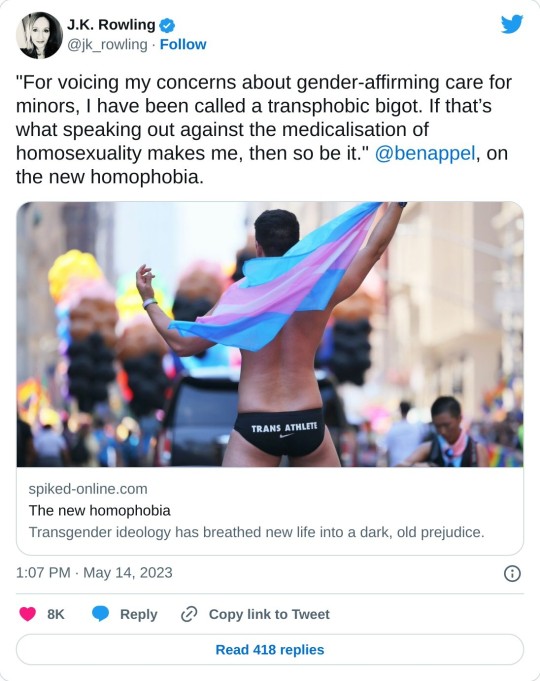

For voicing my concerns about gender-affirming care for minors, I have been called a transphobic bigot. If that’s what speaking out against the medicalisation of homosexuality makes me, then so be it.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Eni Update!

She's about a month old now! This week she spent 2 nights at my friend's house (the one who found her and brought her to me, actually!) While my family and I were away. I had hoped that they would want to keepheras a pet, but unfortunately they have a very small home and a very rambunctious puppy who would be too dangerous for her.

So she returned to me on friday, and promptly moved into the bigger tank!

I forgot if i made a post about it or not, and i couldn't find one with the search tool, so I'll talk about it anyway.

It's an old fish tank, 80 cm x 35 cm x 40 cm. I made a lid from aluminium fly screen mesh and L-shaped wooden floor trims, and hot glue. it fits realy snugly and still lets in all the air, so it's working out great so far! I'm planning on building an extension to go on top, which will add another 45 cm of height for climbing.

She loves balancing along the sticks and loves the multi - chambered house. I think she's happy, she still comes running whenever i reach in - she loves pets and snuggles. Unfortunately she's a bit too fast/wriggly/ difficult to come out to hang with me on my bed now, lol. Maybe she'll mellow out a bit when she gets older.

I love her so much. She's a good little mouse! I wish I could get her a friend, but i've read that it's not a great idea to introduce pet mice to her, they are not the same species and cannot communicate or reproduce. (I do NOT want baby mice, at all costs).

Well, for now she'll be my pampered pet. If an opportunity arises to get her a buddy I'll give it a try.

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Aude Pariset, Hungry Bin (Cooler Bag), 2016 (floor)

Fabric, aluminium, mesh, extruded polystyrene, Remnants from tenebrio molitor worms, 45 x 36 x 28cm

Sandy Brown, Berlin

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A sculpture titled 'Flying Egret (Lifesize Bird Garden Pond Hanging statue)' by sculptor Kenneth Potts. In a medium of Aluminium Tube, Mesh Sheeting and in an edition of 1/1.

1 note

·

View note

Text

#Aluminium Profile Manufacturers in Jaipur#Wire Netting Manufacturers in Jaipur#Wire Mesh Manufacturers in Jaipur

0 notes

Photo

4t2 Movie Hangout Triomphant curtains with trim repo’d to BG aluminium blinds

These are the conversions by @morepopcorn but with the trim repo’d to the BG aluminium blinds because I wanted more color options for the trim without the need of making new recolors when they can just use... already existing ones ?+ it will use smaller textures so it’s always better for our games. I also made them a bit more expensive because it felt more logical to me. As the original conversion, the right curtain takes its texture from the left one. 758 polys.

Download : SFS

Cost : 230$

poke @sims4t2bb

2022/08/12 fixed tiny missing mesh part on the rod

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Ben Appel

Published: May 14, 2023

When I was a young boy, I loved spending the night at my grandmother’s house. There, I could stay up as late as I wanted, and in the morning, there would always be Cinnamon Toast Crunch for breakfast. But the best part was raiding the closet in her basement, which was full of the gowns she had worn in the 1960s and 1970s – frilly pink and purple confections made of lace, chiffon and silk. I would put them on and watch The Golden Girls, sophisticatedly sipping Coke from a wine glass.

When I was nine, my dad bought a video camera, a giant monstrosity that my siblings and I struggled to balance on our shoulders while we filmed home videos. Alone, I’d prop the camera on the coffee table and record myself modelling various outfits, explaining to the camera why this plaid shirt went with these cargo shorts, or why this teal Starter jacket complemented these acid-washed jeans so perfectly. I captured on camera the dance I had painstakingly choreographed to Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch’s ‘Good Vibrations’.

As a kid, I followed my two older sisters around like a shadow, mimicking their mannerisms – the way they tucked loose strands of hair behind their ears when they were concentrating on their maths homework; the way they jutted their hips whenever they were talking to cute boys. Like them, I was a naturally athletic kid. My favourite sport was lacrosse, but I much preferred to play with the girls instead of the boys. The boys were quick to push and shove, and they loved to whack each other with their aluminium sticks. Girls relied more on their speed, their reflexes and the skills they’d honed to keep the ball securely cradled in the shallow mesh of their wooden sticks.

I grew up in a fundamentalist Christian community – most people would call it a cult. From kindergarten to the sixth grade, I attended the community’s tiny school. Because enrollment was so low, there was no in-crowd, no separate cliques of jocks and geeks. In retrospect, I’m sure my classmates and especially my teachers noticed my gender-nonconformity – all of my home videos prove that it was glaring – but it went largely ignored. All that mattered was that we were good Christians, that we loved Jesus and evangelised God’s Word to as many people as possible. When I learned about homosexuals in Bible class, or about AIDS (which we were told God had created to punish homosexuals for their sins), I didn’t think for a moment that I was one of them. Sure, my first real crush, when I was 11, had been on a boy – Elijah Wood, an actor about my age whose performance in the 1994 B-movie, North, had captured my heart. But at the time, before sexual maturity, I mistook the longing I felt for Elijah with the more sanitised desire to simply keep his company and be his best friend. I indiscriminately absorbed all of the lessons I learned about homosexuals, as if they were and would always be irrelevant to my life.

The summer after my sixth-grade year, my family left the community and we moved to a neighbouring town. I began seventh grade in a large public school, where there was definitely an in-crowd. My new classmates wasted little time informing me how unacceptable it was for a boy like me to behave the way I did – the way I enunciated my s-words, the way I brushed my auburn hair, which I had highlighted the previous summer with Sun-In. They called me a faggot, delivered me notes that said everyone knew my ‘dirty little secret’. They asked me frequently, ‘Are you a boy or a girl?’. Well, of course I was a boy, I would respond, trembling.

Meanwhile, I was beginning to sexually mature; I was soon developing crushes that inspired more than just a desire to keep a boy’s company. With horror, I realised that I might actually be what the kids were calling me – which, I knew in my bones, guaranteed me a tragically short life and a one-way ticket to hell. That, after all, was what the old form of homophobia entailed. Self-loathing.

To survive the onslaught, I defeminised myself. I lowered my voice, started wearing baggy jeans and sweatshirts, cut the highlights out of my hair, and replaced my Mariah Carey CDs with Nirvana. Soon, the fear and the anxiety became too much to bear, and the only refuge I found was in alcohol and drugs.

In high school, with each passing year, my drug use got worse. After graduation, I lasted one semester in college before dropping out. Two months later, at the age of 19, I had my first of several stays in a local psychiatric ward. I was delusional, addicted to drugs and suicidal.

It was during my second stay in the psychiatric ward that I was introduced to a 12-step programme, which was how I would eventually get sober in my early twenties. It was slow-going in the beginning of my sobriety to accept my homosexuality. I began to reconnect with the young boy I had once been, the boy whose interests expanded beyond what was typical for males. I experimented with bronzer and mascara, and got French manicures and pedicures.

Engaging in these behaviours felt liberating for a while, but eventually the novelty wore off. In fact, they started to feel performative. I realised I didn’t need those things to be my authentic self. My ideas, my voice, the way I treat other people – these are the things that make me the person I truly am.

In 2011, when I was 28, I fell in love with a man. The following year, I joined the fight for marriage equality. After we won that campaign, I knew I wanted to become a gay activist. I wanted to help create a world in which feminine boys and butch girls could exist peacefully in society. A world in which gender-nonconforming people were accepted as natural variations of their own sex. Minorities, sure, but real and valid nonetheless.

The trans question

In 2017, at the age of 33, I enrolled at Columbia University, New York to complete my undergraduate degree. There, I was shocked to discover how gay activism had evolved since marriage equality became the law of the land. The focus was now entirely on personal pronouns and on being ‘queer’. My classmates labelled me ‘cis’, short for cisgender. I didn’t even know what it meant. All I knew was that they called me ‘cis’ in the same cadence that the seventh graders had called me ‘fag’.

Soon, I learned about nonbinary identities, and that some people – many people – were literally arguing that sex, not gender, was a social construct. I met people who evangelised a denomination of transgenderism that I had never heard of, one that included people who had never been gender dysphoric and who had no desire to medically transition. I met straight people whose ‘trans / nonbinary’ identities seemed to be defined by their haircuts, outfits and inchoate politics. I met straight women with Grindr accounts, and listened to them complain about the ‘transphobic’ gay men who didn’t want to have sex with women.

All around me, it seemed, straight people were spontaneously identifying into my community and then policing our behaviours and customs. I began to think that this broadening of the ‘trans’ and ‘queer’ umbrella was giving a hell of a lot of people a free pass to express their homophobia.

At Columbia, I took classes on LGBT history, but much of that history was delivered through the lens of queer theory. Queer theorists appropriate French philosopher Michel Foucault’s ideas about the power of language in constructing reality. They argue that homosexuality didn’t exist prior to the late 19th century, when the word ‘homosexual’ first appeared in medical discourse. Queer theorists proselytise a liberation that supposedly results from challenging the concepts of empirical reality and ‘normativity’. But their converts instead often end up adrift in a sea of nihilism. Queer theory, which has become the predominant method of discussing and analysing gender and sexuality in universities, seemed to me to be more ideological than truthful.

In my classes on gender and sexuality in the Muslim world, however, I discovered something else, too. I learned about current medical practices in Iran, where gay sex is illegal and punishable by death, and where medical transition is subsidised by the state to ‘cure’ gays and lesbians who, the theocratic elite insists, are ‘normal’ people ‘trapped in the wrong bodies’. I privately drew parallels between the anti-gay laws and practices of Iran and what I saw developing in the West, but I convinced myself I was just being paranoid.

Then, I learned about what was happening to gender-nonconforming kids – that they were being prescribed off-label drugs to halt their natural development, so that they’d have time to decide if they were really transgender. If so, they would then be more successful at passing as the opposite sex in adulthood. Even worse, I learned that these practices were being touted by LGBT-rights organisations as ‘life-saving medical care’.

It felt like I was living in an episode of The Twilight Zone. How long were these kids supposed to remain on the blockers? And what happens in a few years, if they decide they’re not ‘truly trans’ after all, and all of their peers have surpassed them? Are they seriously supposed to commence puberty at 16 or 17 years of age? These questions rattled my brain for months, until I learned the actual statistics: nearly all children who are prescribed puberty blockers go on to receive cross-sex hormones. Blockers don’t give a kid time to think. They solidify him in a trans identity and sentence him to a lifetime of very expensive, experimental medicalisation.

I wondered how different these so-called trans kids were from the little boy I had been. Obviously, I grew up to be a gay man and not a transwoman. But how could gender clinicians tell the difference between a young boy expressing his homosexuality through gender nonconformity, and someone ‘born in the wrong body’? I decided to dig deeper into the real history of medical transition.

Medicalising homosexuality

What I learned validated all of my worst fears. I learned that for decades after their invention, synthetic ‘sex hormones’ were used by doctors and scientists who sought to ‘cure’ homosexuality, and by law enforcement to chemically castrate men convicted of committing homosexual acts.

I learned about actress and singer Christine Jorgensen, one of the first people in the US to become widely known for having ‘sex-reassignment’ surgery in the early 1950s. Jorgensen may now be celebrated by the modern ‘LGBTQIA+’ community as a trans icon, but he seemed more concerned with escaping his homosexuality, which he said was ‘deeply alien to my religious attitudes’. As Jorgensen put it, ‘I identified myself as female and consequently my interests in men were normal’.

I learned that of the first adolescents to be treated for gender dysphoria (or what was then called ‘gender identity disorder’) with puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones in the 1990s and early 2000s, the vast majority were homosexual. And I learned that these studies inform current ‘gender-affirming care’ practices.

Soon, I met detransitioned gay men who had sought an escape from internalised and external homophobia in a transgender identity. They continue to suffer severe post-surgical complications, years after their vaginoplasties.

I began to fear we had reached a point of no return a couple of years ago, during a conversation I had with a supposedly ‘progressive’ friend. I told her that, if I had been a young boy now, I likely would have been prescribed puberty blockers and gone on to medically transition. ‘And you don’t think you would’ve been happy as a transwoman?’, she asked me. Her question left me speechless. I couldn’t find the words to state the obvious: that I am a gay man, not a transwoman; that statistics tell me my medical transition may not have been successful; and that I would suffer severe medical complications. In any case, if I had transitioned, I wouldn’t be living an authentic life. After all, isn’t that what this is supposed to be about? Living authentically?

Sylvester, an androgynous disco icon of the 1970s and 1980s, was once asked what gay liberation meant to him. He answered, ‘I could be the queen that I really was without having a sex change or being on hormones’. Perhaps I belong in an earlier era, when newly liberated gays and lesbians rebelled against the medical and psychiatric experiments they had long been subjected to. Perhaps my early aspiration of expanding what it means to be a boy or a girl was nothing but a pipe dream. In Europe, there is hope that these medical experiments will cease, and that gay and lesbian adolescents will be spared from a lifetime of medicalisation. But in the US, nearly eight years after same-sex marriage became the law of the land, it is full-steam ahead with these homophobic practices.

For voicing my concerns about gender-affirming care for minors, I have been called a transphobic bigot. If that’s what speaking out against the medicalisation of homosexuality makes me, then so be it.

-

Ben Appel is a writer based in New York. His forthcoming memoir, Cis White Gay: The Making of a Gender Heretic, will be published by Post Hill Press.

==

How on Earth did we get to the point where so many people are engaged in this shared delusion? A type of magical thinking about the infinite malleability of humans, human biology and the human psyche.

What it resembles is a visceral distaste for the human body and biology, cages constructed for the purpose of imprisoning the helpless gender thetans that are condemned to live trapped within them as punishment for slights against Xenu.

But you are not in your body. You are your body. You can't be "born in the wrong body" because you are the thing your body does.

#Ben Appel#gay conversion therapy#conversion therapy#homophobia#woke homophobia#magical thinking#shared delusion#anti gay#gender ideology#queer theory#trans the gay away#trans away the gay#gender thetans#religion is a mental illness

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tips for Finding the Right Metal Fabricator in Sydney!

A metal fabricator in Sydney stands between you and your dream, so it's essential that you choose the right one. You can avoid trouble by doing your research. Here, we've provided tips to help you find the best fabrication services in Sydney for your project.

Choosing a Metal Fabricator Sydney: What to Look For

Look for experience and expertise

The best custom metal fabrication companies and sheet metal fabricators offers years of experience and know how to work with a variety of metals. They can also handle complex projects without any trouble.

Professional steel fabrication teams are also equipped with the latest technology, equipment, machinery and specialist tools that makes it possible for them to deliver quality steel fabrications and services.

Check out their portfolio

A good fabricator will have a portfolio of previous projects that they’ve worked on. This will give you an idea of their capabilities and style.

The company portfolio can also be your guide to see the different types of services that they offer. Do they work on stainless steel, powder coating, laser cutting services, welding, and the like. You can see if they work on different types of materials like steel, aluminium, and stainless steel or if they specialise on only one type of material. You’ll save time asking if you can access all of this in their portfolio.

Make sure they are licensed and insured

Any reputable metal fabrication companies will be licensed and insured. This protects you in case of any accidents or damages that may occur during the project. As clients, you should only work with a fabrication business capable or providing such licenses to ensure that all your metal fabrication needs are indeed delivered within Australian standards. Read more

#chain wire fencing#chain wire fencing supplies#black chain wire fencing#gabion walls#aluminium louvres#Steel Fence#358 Mesh

1 note

·

View note