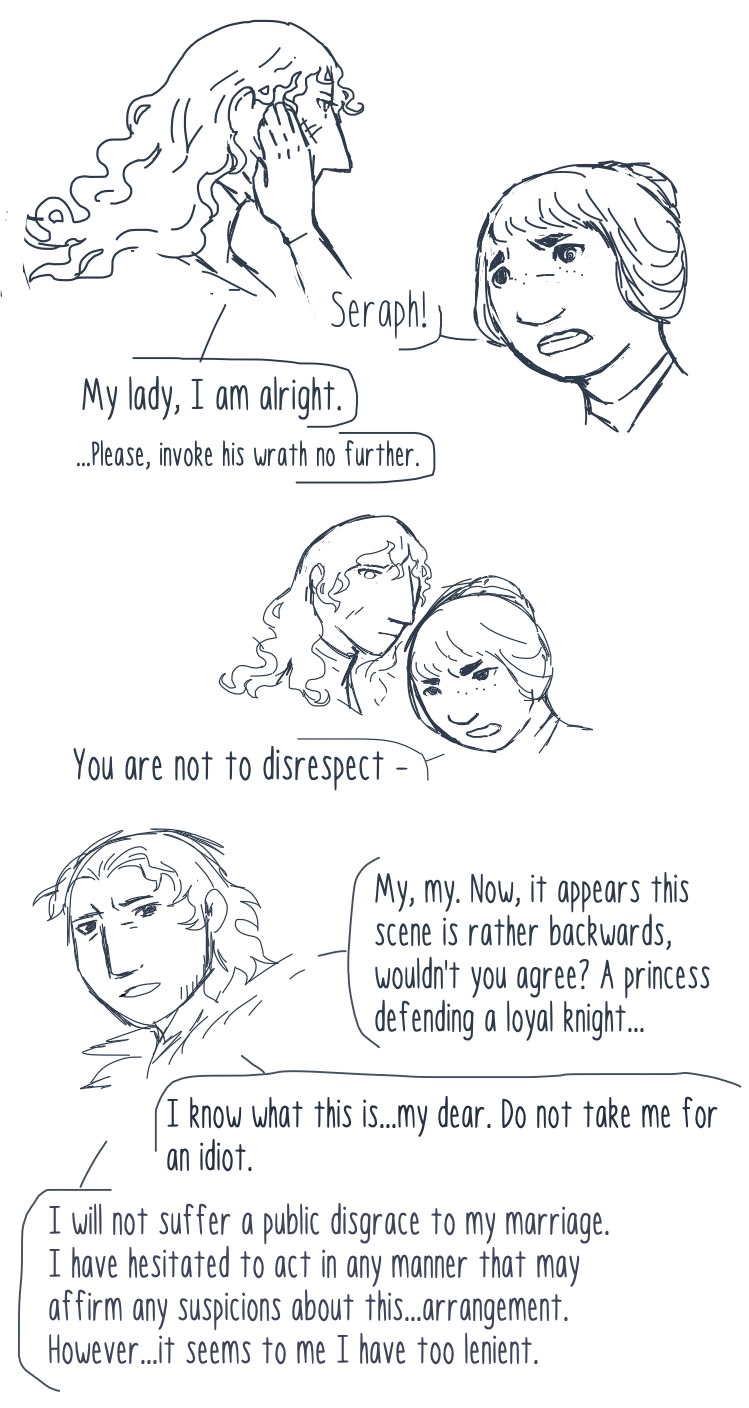

#and the prince has a not great reputation already they think hes unlucky as a sign of disfavor from the gods. well thats

Text

the prince. who still doesnt have a name yet

#talks#knight oc#sorry for the long ass... *leaves.*#seraph doesnt normally get scared quite like this but shes afraid something will happen that she wont#do a thing about out of duty/cowardice/not wanting to make things worse.#luna doesnt normally get angry like this.#and the prince has a not great reputation already they think hes unlucky as a sign of disfavor from the gods. well thats#some castle gossip. but hes like if there cannot be a scandal about my marriage too they#will think me unfit to rule

23 notes

·

View notes

Link

This book will concern itself least of all with those unrelated psychological researches which are now so often substituted for social and historical analysis. Foremost in our field of vision will stand the great, moving forces of history, which are super-personal in character. Monarchy is one of them. But all these forces operate through people. And monarchy is by its very principle bound up with the personal. This in itself justifies an interest in the personality of that monarch whom the process of social development brought face to face with a revolution. Moreover, we hope to show in what follows, partially at least, just where in a personality the strictly personal ends – often much sooner than we think – and how frequently the “distinguishing traits” of a person are merely individual scratches made by a higher law of development.

Nicholas II inherited from his ancestors not only a giant empire, but also a revolution. And they did not bequeath him one quality which would have made him capable of governing an empire or even a province or a county. To that historic flood which was rolling its billows each one closer to the gates of his palace, the last Romanov opposed only a dumb indifference. It seemed as though between his consciousness and his epoch there stood some transparent but absolutely impenetrable medium.

People surrounding the tzar often recalled after the revolution that in the most tragic moments of his reigns – at the time of the surrender of Port Arthur and the sinking of the fleet at Tsushima, and ten years later at the time of the retreat of the Russian troops from Galicia, and then two years later during the days preceding his abdication when all those around him were depressed, alarmed, shaken – Nicholas alone preserved his tranquillity. He would inquire as usual how many versts he had covered in his journeys about Russia, would recall episodes of hunting expeditions in the past, anecdotes of official meetings, would interest himself generally in the little rubbish of the day’s doings, while thunders roared over him and lightnings flashed. “What is this?” asked one of his attendant generals, “a gigantic, almost unbelievable self-restraint, the product of breeding, of a belief in the divine predetermination of events? Or is it inadequate consciousness?” The answer is more than half included in the question. The so-called “breeding” of the tzar, his ability to control himself in the most extraordinary circumstances, cannot be explained by a mere external training; its essence was an inner indifference, a poverty of spiritual forces, a weakness of the impulses of the will. That mask of indifference which was called breeding in certain circles, was a natural part of Nicholas at birth.

The tzar’s diary is the best of all testimony. From day to day and from year to year drags along upon its pages the depressing record of spiritual emptiness. “Walked long and killed two crows. Drank tea by daylight.” Promenades on foot, rides in a boat. And then again crows, and again tea. All on the borderline of physiology. Recollections of church ceremonies are jotted down in the same tone as a drinking party.

In the days preceding the opening of the State Duma, when the whole country was shaking with convulsions, Nicholas wrote: “April 14. Took a walk in a thin shirt and took up paddling again. Had tea in a balcony. Stana dined and took a ride with us. Read.” Not a word as to the subject of his reading. Some sentimental English romance? Or a report from the Police Department? “April 15: Accepted Witte’s resignation. Marie and Dmitri to dinner. Drove them home to the palace.”

On the day of the decision to dissolve the Duma, when the court as well as the liberal circles were going through a paroxysm of fright, the tzar wrote in his diary: “July 7. Friday. Very busy morning. Half hour late to breakfast with the officers ... A storm came up and it was very muggy. We walked together. Received Goremykin. Signed a decree dissolving the Duma! Dined with Olga and Petia. Read all evening.” An exclamation point after the coming dissolution of the Duma is the highest expression of his emotions. The deputies of the dispersed Duma summoned the people to refuse to pay taxes. A series of military uprisings followed: in Sveaborg, Kronstadt, on ships, in army units. The revolutionary terror against high officials was renewed on an unheard-of scale. The tzar writes: “July 9. Sunday. It has happened! The Duma was closed today. At breakfast after Mass long faces were noticeable among many ... The weather was fine. On our walk we met Uncle Misha who came over yesterday from Gatchina. Was quietly busy until dinner and all evening. Went padding in a canoe.” It was in a canoe he went paddling – that is told. But with what he was busy all evening is not indicated. So it was always.

And further in those same fatal days: “July 14. Got dressed and rode a bicycle to the bathing beach and bathed enjoyably in the sea.” “July 15. Bathed twice. It was very hot. Only us two at dinner. A storm passed over.” “July 19. Bathed in the morning. Received at the farm. Uncle Vladimir and Chagin lunched with us.” An insurrection and explosions of dynamite are barely touched upon with a single phrase, “Pretty doings!” – astonishing in its imperturbable indifference, which never rose to conscious cynicism.

“At 9:30 in the morning we rode out to the Caspian regiment ... walked for a long time. The weather was wonderful. Bathed in the sea. After tea received Lvov and Guchkov.” Not a word of the fact that this unexpected reception of the two liberals was brought about by the attempt of Stolypin to include opposition leaders in his ministry. Prince Lvov, the future head of the Provisional Government, said of that reception at the time: “I expected to see the sovereign stricken with grief, but instead of that there came out to meet me a jolly sprightly fellow in a raspberry-coloured shirt.” The tzar’s outlook was not broader than that of a minor police official – with this difference, that the latter would have a better knowledge of reality and be less burdened with superstitions. The sole paper which Nicholas read for years, and from which he derived his ideas, was a weekly published on state revenue by Prince Meshchersky, a vile, bribed journalist of the reactionary bureaucratic clique, despised even in his own circle. The tzar kept his outlook unchanged through two wars and two revolutions. Between his consciousness and events stood always that impenetrable medium – indifference. Nicholas was called, not without foundation, a fatalist. It is only necessary to add that his fatalism was the exact opposite of an active belief in his “star.” Nicholas indeed considered himself unlucky. His fatalism was only a form of passive self-defence against historic evolution, and went hand in hand with an arbitrariness, trivial in psychological motivation, but monstrous in its consequences.

“I wish it and therefore it must be —,” writes Count Witte. “That motto appeared in all the activities of this weak ruler, who only through weakness did all the things which characterised his reign – a wholesale shedding of more or less innocent blood, for the most part without aim.”

Nicholas is sometimes compared with his half-crazy great-great-grandfather Paul, who was strangled by a camarilla acting in agreement with his own son, Alexander “the Blessed.” These two Romanovs were actually alike in their distrust of everybody due to a distrust of themselves, their touchiness as of omnipotent nobodies, their feeling of abnegation, their consciousness, as you might say, of being crowned pariahs. But Paul was incomparably more colourful; there was an element of fancy in his rantings, however irresponsible. In his descendant everything was dim; there was not one sharp trait.

Nicholas was not only unstable, but treacherous. Flatterers called him a charmer, bewitcher, because of his gentle way with the courtiers. But the tzar reserved his special caresses for just those officials whom he had decided to dismiss. Charmed beyond measure at a reception, the minister would go home and find a letter requesting his resignation. That was a kind of revenge on the tzar’s part for his own nonentity.

Nicholas recoiled in hostility before everything gifted and significant. He felt at ease only among completely mediocre and brainless people, saintly fakers, holy men, to whom he did not have to look up. He had his amour propre, indeed it was rather keen. But it was not active, not possessed of a grain of initiative, enviously defensive. He selected his ministers on a principle of continual deterioration. Men of brain and character he summoned only in extreme situations when there was no other way out, just as we call in a surgeon to save our lives. It was so with Witte, and afterwards with Stolypin. The tzar treated both with ill-concealed hostility. As soon as the crisis had passed, he hastened to part with these counsellors who were too tall for him. This selection operated so systematically that the president of the last Duma, Rodzianko, on the 7th of January 1917, with the revolution already knocking at the doors, ventured to say to the tzar: “Your Majesty, there is not one reliable or honest man left around you; all the best men have been removed or have retired. There remain only those of ill repute.”

All the efforts of the liberal bourgeoisie to find a common language with the court came to nothing. The tireless and noisy Rodzianko tried to shake up the tzar with his reports, but in vain. The latter gave no answer either to argument or to impudence, but quietly made ready to dissolve the Duma. Grand Duke Dmitri, a former favourite of the tzar, and future accomplice in the murder of Rasputin, complained to his colleague, Prince Yussupov, that the tzar at headquarters was becoming every day more indifferent to everything around him. In Dmitri’s opinion the tzar was being fed some kind of dope which had a benumbing action upon his spiritual faculties. “Rumours went round,” writes the liberal historian Miliukov, “that this condition of mental and moral apathy was sustained in the tzar by an increased use of alcohol.” This was all fancy or exaggeration. The tzar had no need of narcotics: the fatal “dope” was in his blood. Its symptoms merely seemed especially striking on the background of those great events of war and domestic crisis which led up to the revolution. Rasputin, who was a psychologist, said briefly of the tzar that he “lacked insides.”

This dim, equable and “well-bred” man was cruel – not with the active cruelty of Ivan the Terrible or of Peter, in the pursuit of historic aims – What had Nicholas the Second in common with them? – but with the cowardly cruelty of the late born, frightened at his own doom. At the very dawn of his reign Nicholas praised the Phanagoritsy regiment as “fine fellows” for shooting down workers. He always “read with satisfaction” how they flogged with whips the bob-haired girl-students, or cracked the heads of defenceless people during Jewish pogroms. This crowned black sheep gravitated with all his soul to the very dregs of society, the Black Hundred hooligans. He not only paid them generously from the state treasury, but loved to chat with them about their exploits, and would pardon them when they accidentally got mixed up in the murder of an opposition deputy. Witte, who stood at the head of the government during the putting down of the first revolution, has written in his memoirs: “When news of the useless cruel antics of the chiefs of those detachments reached the sovereign, they met with his approval, or in any case his defence.” In answer to the demand of the governor-general of the Baltic States that he stop a certain lieutenant-captain, Richter, who was “executing on his own authority and without trial non-resistant persons,” the tzar wrote on the report: “Ah, what a fine fellow!” Such encouragements are innumerable. This “charmer,” without will, without aim, without imagination, was more awful than all the tyrants of ancient and modern history.

The tzar was mightily under the influence of the tzarina, an influence which increased with the years and the difficulties. Together they constituted a kind of unit – and that combination shows already to what an extent the personal, under pressure of circumstances, is supplemented by the group. But first we must speak of the tzarina herself.

Maurice Paléologue, the French ambassador at Petrograd during the war, a refined psychologist for French academicians and janitresses, offers a meticulously licked portrait of the last tzarina: “Moral restlessness, a chronic sadness, infinite longing, intermittent ups and downs of strength, anguishing thoughts of the invisible other world, superstitions – are not all these traits, so clearly apparent in the personality of the empress, the characteristic traits of the Russian people?” Strange as it may seem, there is in this saccharine lie just a grain of truth. The Russian satirist Saltykov, with some justification, called the ministers and governors from among the Baltic barons “Germans with a Russian soul.” It is indubitable that aliens, in no way connected with the people, developed the most pure culture of the “genuine Russian” administrator.

But why did the people repay with such open hatred a tzarina who, in the words of Paléologue, had so completely assimilated their soul? The answer is simple. In order to justify her new situation, this German woman adopted with a kind of cold fury all the traditions and nuances of Russian mediaevalism, the most meagre and crude of all mediaevalisms, in that very period when the people were making mighty efforts to free themselves from it. This Hessian princess was literally possessed by the demon of autocracy. Having risen from her rural corner to the heights of Byzantine despotism, she would not for anything take a step down. In the orthodox religion she found a mysticism and a magic adapted to her new lot. She believed the more inflexibly in her vocation, the more naked became the foulness of the old régime. With a strong character and a gift for dry and hard exaltations, the tzarina supplemented the weak-willed tzar, ruling over him.

On March 17, 1916, a year before the revolution, when the tortured country was already writhing in the grip of defeat and ruin, the tzarina wrote to her husband at military headquarters: “You must not give indulgences, a responsible ministry, etc. ... or anything that they want. This must be your war and your peace, and the honour yours and our fatherland’s, and not by any means the Duma’s. They have not the right to say a single word in these matters.” This was at any rate a thoroughgoing programme. And it was in just this way that she always had the whip hand over the continually vacillating tzar.

After Nicholas’ departure to the army in the capacity of fictitious commander-in-chief, the tzarina began openly to take charge of internal affairs. The ministers came to her with reports as to a regent. She entered into a conspiracy with a small camarilla against the Duma, against the ministers, against the staff-generals, against the whole world – to some extent indeed against the tzar. On December 6, 1916, the tzarina wrote to the tzar: “... Once you have said that you want to keep Protopopov, how does he (Premier Trepov) go against you? Bring down your first on the table. Don’t yield. Be the boss. Obey your firm little wife and our Friend. Believe in us.” Again three days late: “You know you are right. Carry your head high. Command Trepov to work with him ... Strike your fist on the table.” Those phrases sound as though they were made up, but they are taken from authentic letters. Besides, you cannot make up things like that.

On December 13 the tzarina suggested to the tzar: “Anything but this responsible ministry about which everybody has gone crazy. Everything is getting quiet and better, but people want to feel your hand. How long they have been saying to me, for whole years, the same thing: ’Russia loves to feel the whip.’ That is their nature!” This orthodox Hessian, with a Windsor upbringing and a Byzantine crown on her head, not only “incarnates” the Russian soul, but also organically despises it. Their nature demands the whip – writes the Russian tzarina to the Russian tzar about the Russian people, just two months and a half before the monarchy tips over into the abyss.

In contrast to her force of character, the intellectual force of the tzarina is not higher, but rather lower than her husband’s. Even more than he, she craves the society of simpletons. The close and long-lasting friendship of the tzar and tzarina with their lady-in-waiting Vyrubova gives a measure of the spiritual stature of this autocratic pair. Vyrubova has described herself as a fool, and this is not modesty. Witte, to whom one cannot deny an accurate eye, characterised her as “a most commonplace, stupid, Petersburg young lady, homely as a bubble in the biscuit dough.” In the society of this person, with whom elderly officials, ambassadors and financiers obsequiously flirted, and who had just enough brains not to forget about her own pockets, the tzar and tzarina would pass many hours, consulting her about affairs, corresponding with her and about her. She was more influential than the State Duma, and even than the ministry.

But Vyrubova herself was only an instrument of “The Friend,” whose authority superseded all three. “... This is my private opinion,” writes the tzarina to the tzar, “I will find out what our Friend thinks.” The opinion of the “Friend” is not private, it decides. “... I am firm,” insists the tzarina a few weeks later, “but listen to me, i.e. this means our Friend, and trust in everything ... I suffer for you as for a gentle soft-hearted child – who needs guidance, but listens to bad counsellors, while a man sent by God is telling him what he should do.”

The Friend sent by God was Gregory Rasputin.

“... The prayers and the help of our Friend – then all will be well.”

“If we did not have Him, all would have been over long ago. I am absolutely convinced of that.”

Throughout the whole reign of Nicholas and Alexandra soothsayers and hysterics were imported for the court not only from all over Russia, but from other countries. Special official purveyors arose, who would gather around the momentary oracle, forming a powerful Upper Chamber attached to the monarch. There was no lack of bigoted old women with the title of countess, nor of functionaries weary of doing nothing, nor of financiers who had entire ministries in their hire. With a jealous eye on the unchartered competition of mesmerists and sorcerers, the high priesthood of the Orthodox Church would hasten to pry their way into the holy of holies of the intrigue. Witte called this ruling circle, against which he himself twice stubbed his toe, “the leprous court camarilla.”

The more isolated the dynasty became, and the more unsheltered the autocrat felt, the more he needed some help from the other world. Certain savages, in order to bring good weather, wave in the air a shingle on a string. The tzar and tzarina used shingles for the greatest variety of purposes. In the tzar’s train there was a whole chapel full of large and small images, and all sorts of fetiches, which were brought to bear, first against the Japanese, then against the German artillery.

The level of the court circle really had not changed much from generation to generation. Under Alexander II, called the “Liberator,” the grand dukes had sincerely believed in house spirits and witches. Under Alexander III it was no better, only quieter. The “leprous camarilla” had existed always, changed only its personnel and its method. Nicholas II did not create, but inherited from his ancestors, this court atmosphere of savage mediaevalism. But the country during these same decades had been changing, its problems growing more complex, its culture rising to a higher level. The court circle was thus left far behind.

Although the monarchy did under compulsion make concessions to the new forces, nevertheless inwardly it completely failed to become modernised. On the contrary it withdrew into itself. Its spirit of mediaevalism thickened under the pressure of hostility and fear, until it acquired the character of a disgusting nightmare overhanging the country.

Towards November 1905 – that is, at the most critical moment of the first revolution – the tzar writes in his diary: “We got acquainted with a man of God, Gregory, from the Tobolsk province.” That was Rasputin – a Siberian peasant with a bald scar on his head, the result of a beating for horse-stealing. Put forward at an appropriate moment, this “Man of God” soon found official helpers – or rather they found him – and thus was formed a new ruling class which got a firm hold of the tzarina, and through her of the tzar.

From the winter of 1913-14 it was openly said in Petersburg society that all high appointments, posts and contracts depended upon the Rasputin clique. The “Elder” himself gradually turned into a state institution. He was carefully guarded, and no less carefully sought after by the competing ministers. Spies of the Police Department kept a diary of his life by hours, and did not fail to report how on a visit to his home village of Pokrovsky he got into a drunken and bloody fight with his own father on the street. On the same day that this happened – September 9, 1915 – Rasputin sent two friendly telegrams, one to Tzarskoe Selo, to the tzarina, the other to headquarters to the tzar. In epic language the police spies registered from day to day the revels of the Friend. “He returned today 5 o’clock in the morning completely drunk.” “On the night of the 25-26th the actress V. spent the night with Rasputin.” “He arrived with Princess D. (the wife of a gentleman of the bedchamber of the Tzar’s court) at the Hotel Astoria.”...And right beside this: “Came home from Tzarskoe Selo about 11 o’clock in the evening.” “Rasputin came home with Princess Sh- very drunk and together they went out immediately.” In the morning or evening of the following day a trip to Tzarskoe Selo. To a sympathetic question from the spy as to why the Elder was thoughtful, the answer came: “Can’t decide whether to convoke the Duma or not.” And then again: “He came home at 5 in the morning pretty drunk.” Thus for months and years the melody was played on three keys: “Pretty drunk,” “Very drunk,” and “Completely drunk.” These communications of state importance were brought together and countersigned by the general of gendarmes, Gorbachev.

The bloom of Raputin’s influence lasted six years, the last years of the monarchy. “His life in Petrograd,” says Prince Yussupov, who participated to some extent in that life, and afterward killed Rasputin, “became a continual revel, the durnken debauch of a galley slave who had come into an unexpected fortune.” “I had at my disposition,” wrote the president of the Duma, Rodzianko, “a whole mass of letters from mothers whose daughters had been dishonoured by this insolent rake.” Nevertheless the Petrograd metropolitan, Pitirim, owed his position to Rasputin, as also the almost illiterate Archbishop Varnava. The Procuror of the Holy Synod, Sabler, was long sustained by Rasputin; and Premier Kokovtsev was removed at his wish, having refused to receive the “Elder.” Rasputin appointed Stürmer President of the Council of Ministers, Protopopov Minister of the Interior, the new Procuror of the Synod, Raev, and many others. The ambassador of the French republic, Paléologue, sought an interview with Rasputin, embraced him and cried, “Voilà, un véritable illuminé!” hoping in this way to win the heart of the tzarina to the cause of France. The Jew Simanovich, financial agent of the “Elder,” himself under the eye of the Secret Police as a nightclub gambler and usurer – introduced into the Ministry of Justice through Rasputin the completely dishonest creature Dobrovolsky.

“Keep by you the little list,” writes the tzarina to the tzar, in regard to new appointments. “Our friend has asked that you talk all this over with Protopopov.” Two days later: “Our friend says that Stürmer may remain a few days longer as President of the Council of Ministers.” And again: “Protopopov venerates our friend and will be blessed.”

On one of those days when the police spies were counting up the number of bottles and women, the tzarina grieved in a letter to the tzar: “They accuse Rasputin of kissing women, etc. Read the apostles; they kissed everybody as a form of greeting.” This reference to the apostles would hardly convince the police spies. In another letter the tzarina goes still farther. “During vespers I thought so much about our friend,” she writes, “how the Scribes and Pharisees are persecuting Christ pretending that they are so perfect ... yes, in truth no man is a prophet in his own country.”

The comparison of Rasputin and Christ was customary in that circle, and by no means accidental. The alarm of the royal couple before the menacing forces of history was too sharp to be satisfied with an impersonal God and the futile shadow of a Biblical Christ. They needed a second coming of “the Son of Man.” In Rasputin the rejected and agonising monarchy found a Christ in its own image.

“If there had been no Rasputin,” said Senator Tagantsev, a man of the old régime, “it would have been necessary to invent one.” There is a good deal more in these words than their author imagined. If by the word hooliganism we understand the extreme expression of those anti-social parasite elements at the bottom of society, we may define Rasputinism as a crowned hooliganism at its very top.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Manga the Week of 12/20/17

SEAN: Are you ready? 3-2-1 let’s jam.

MICHELLE: *cracks knuckles in a preparatory fashion*

ASH: Get everybody and the stuff together, because there’s a lot of it!

KATE: There is SO MUCH MANGA that even I had to chime in.

SEAN: We start with Bookwalker, who has the second volume of their light novel The Combat Baker and the Automaton Waitress. I felt it was a good series for them to pick up (certainly better than their other LN series), and will be getting this volume.

J-Novel Club has the 4th volume of Arifureta: From Commonplace to World’s Strongest, which remains the top choice for those who like overpowered isekai and take it Very Seriously Indeed.

Kodansha has many, many things, both digital and print, which I will tackle alphabetically, starting with a 4th All Out!!.

MICHELLE: Woot!

SEAN: Attack on Titan has a big change coming with the 23rd volume, one that (like everything Attack on Titan has ever done) has gotten a mixed reaction.

Cardcaptor Sakura remains one of CLAMP’s most beloved franchise, despite age, appalling Nelvana dubs, and Tsubasa World Chronicle. Now we finally get a sequel with Clear Card, which apparently picks up where the old series left off. I will give it a shot, though I warn you I’m mostly reading for Tomoyo.

MICHELLE: This has been available digitally for a while, and I read it in that format. It’s a cute start, and I loved seeing Kero-chan again.

MELINDA: I’m obviously on board for this.

ANNA: I enjoy early CLAMP, and am leery of recent CLAMP. That being said, due to my love of Cardcaptor Sakura, I will check this out.

ASH: Same! I really do love Cardcaptor Sakura, though.

SEAN: DEATHTOPIA has its 7th and penultimate volume coming out next week.

And there’s also a 4th volume of Elegant Yokai Apartment Life.

If you haven’t yet picked up Ghost in the Shell’s hardcover deluxe editions, why not get them in a handy box set?

We’ve caught up with Japan for Happiness, so it’s nice to see a 6th volume drop.

ASH: I need to catch up with this series, myself!

KATE: The last volume of Happiness had a big time jump and shift in emphasis — something that worked surprisingly well, and and promoted one of the most interesting (and resourceful) supporting characters to a leading role.

SEAN: Inuyashiki comes to an end with its 10th and final volume. It’s always been a bit too weird for me, but then I felt the same way about Gantz.

Kasane has an 8th volume of suspense and horror.

The digital debut next week is The Prince’s Black Poison, a Betsufure romance that honestly sounds like exactly the sort of title I avoid, but what the hey. Recommended for those who like handsome manipulative men. It’s by the author of Gakuen Prince, which was also very much filled with those.

MICHELLE: Oh dear.

ANNA: Feeling sort of meh on this.

SEAN: And Real Girl has a 9th volume of whatever it is Real Girl does, besides remind me how many of these Kodansha digital titles I have yet to sample.

Say “I Love You” has come to its 18th and final volume. Despite the occasional overdose of melodrama, I greatly enjoyed this series, and am happy to see the conclusion after a long wait (we had, again, caught up with Japan).

MICHELLE: I’ve been awaiting this release for a long time!

SEAN: If you haven’t picked up A Silent Voice’s 7 volumes, Kodansha has a box set for you! (Both this and the Ghost in the Shell box are clearly meant for Christmas purchases.)

Speaking of the author of A Silent Voice, we’re getting a 2nd To Your Eternity next week as well.

ASH: Definitely picking this one up. The first volume was very good and surprising in ways that I didn’t expect.

KATE: What Ash said; To Your Eternity is definitely on my short list of Best Sci-Fi manga of 2017.

SEAN: A 6th Tsuredure Children has more 4-koma romance.

And Until Your Bones Rot has a 3rd volume of what is, let’s face it, NOT 4-koma romance.

Seven Seas is next. Arpeggio of Blue Steel is up to its 12th volume, and I’m still really interested in it, which is surprising given it’s about a bunch of cute girls who are really boats.

There’s also a 3rd “not Alice in the Country of Hearts, but the next best thing” series Captive Hearts of Oz.

Unlucky it may be, but the fact that Magical Girl Apocalypse has gotten to Vol. 13 means it’s popular as well.

Seven Seas is starting to pick up light novels that aren’t J-Novel Club print editions, and we begin with Monster Girl Doctor, whose title speaks for itself, though I’m not sure how this falls on the scale between ‘fetishey’ and ‘spooky’ monster girls.

And if that’s too millennial for you, how about a series from the 1980s? We get the first in the Record of Lodoss Wars novels, The Grey Witch, in a fancy hardcover edition.

MELINDA: It’s hard for me to dismiss something from the 80s…

ASH: It really is fancy! I’m looking forward to giving the Lodoss novels a try.

SEAN: Chi’s Sweet Coloring Book is a spinoff from Vertical featuring lots and lots of pictures of Chi to color.

Speaking of cats, Nekomonogatari (Black): Cat Tale is the first of a two-part set in the Monogatari series that finally resolves most of Tsubasa Hanekawa’s ongoing issues.

And there’s also a 4th Flying Witch.

Viz gives us a 3rd Golden Kamuy, which I suspect will have a bit less cooking and a bit more life-threatening violence this time around, but who knows?

ASH: I plan on finding out!

KATE: I seem to be stalking you through this week’s column, Ash! I’m butting in to say GOLDEN KAMUY IS AWESOME. I think Asirpa deserves her own damn series. Heck, it could be a cooking manga and I’d read it.

SEAN: If you want to get someone something terrifying for Christmas, you absolutely can’t go wrong with Shiver, a collection of stories selected by the author, Junji Ito.

ASH: I’m always happy to see more Ito being released! This collection should be great.

KATE: Nothing says “Deck the halls” than a little Junji Ito, I always say.

SEAN: And if you want to give some yuri manga, there’s a 2nd Sweet Blue Flowers omnibus.

MICHELLE: Yay!

ANNA: Behind on this already but I’m gonna read it!

ASH: You absolutely should! I’m so glad this series is finally getting the treatment it deserves in English.

SEAN: Lastly (for Viz only, trust me – we’re not even halfway), we have the 2nd Tokyo Ghoul: re.

And now on to Yen Press, pausing only to scream until our throats are raw and we are coughing up blood. (pause) There we go. Onward.

First off, we have the digital-only titles. Aphorism 13 is the second to last volume, and is for fans of survival manga.

Corpse Princess is up to its 14th volume, but it still has a long way to go. It should appeal to fans of fanservice and zombies.

And Saki 13 means we’re close to catching up, but that’s an ongoing series, so no worries there either. Recommended to those who like mahjong and breasts, not in that order.

On the Yen On side, we finish the digital catch-up for Accel World (9-11) and Irregular at Magic High School (5).

There’s also a new digital release of an older, pre-Yen On title. Kieli was a 2009 series of novels about a girl who can see ghosts, and it had an associated manga as well. Yen now has the digital rights to the novels, so we get the first one next week.

There are also a GIANT number of ongoing and new light novels in print. We get a 12th Accel World, which is in the midst of Haruyuki dealing with another mysterious threat.

The Asterisk War’s 5th volume wraps up its tournament arc, I believe… or should I say, it’s first tournament arc.

Baccano! starts a new 2-volume arc taking place in 1933 and subtitled The Slash. This first volume will show us what happened to that Mexican stereotype of an assassin from the Drug & the Dominoes book.

The Devil Is a Part-Timer! 9 has far less part-time work than expected, as the devil has returned to his homeland to rescue Emi and Alas Ramus.

Goblin Slayer 4 will feature what sounds like a collection of short stories judging from the description. And probably goblins being slayed.

The Irregular at Magic High School’s 6th volume starts a new arc called the Yokohama Disturbance Arc, which I think was the final arc adapted for the anime.

Is It Wrong to Try to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon? asks the same question again, only this time it’s Monsters. Bell says no, others think differently. Vol. 10 drops next week.

KonoSuba’s 4th volume has the inevitable Hot Springs arc.

Rokka: Braves of the Six Flowers has a 3rd volume, and I must admit if the storyline is “who’s the traitor” I may bail.

The first light novel debut is The Saga of Tanya the Evil, which is another isekai. A Japanese HR manager with a cold, ruthless reputation is killed, and then reincarnated by God. Not with the best intentions, though – God dislikes his logical attitude and so puts him in a world where magic exists and there is constant warfare. Oh, and he’s in the body of a little girl.

Sword Art Online has reached a dozen volumes, and we’re still in the midst of the epic Alicization arc. We finally see Alice again, but is she brainwashed? Can Kirito and Eugeo save her?

The other light novel debut this month already has its manga coming out from Kodansha, and is the 2nd of the three ‘ridiculous’ light novels Yen licensed recently. That Time I Got Reincarnated As a Slime arrives next week.

We’re nearly at the end! Only 28 more titles to go! And they’re all Yen Press. We start with a 6th volume of spinoff Akame Ga KILL! ZERO.

Angels of Death is a survival manga with psychological overtimes, which comes from the oddball Comic Gene. I’m not sure what to think of it.

An 8th Aoharu x Machinegun is shipping next week.

And a 5th Bungo Stray Dogs will give us literary references galore.

Light novel adaptations galore! Starting with a 4th manga of Death March to the Parallel World Rhapsody.

Dragons Rioting has a 9th volume, which is also its final volume.

If you like the idea of Goblin Slaying but hate prose, I have good news, the first volume of Goblin Slayer is for you.

I know little about Graineliers except it’s from GFantasy, it has two male leads, and it’s not BL but feels like it should be.

MELINDA: Did you say GFantasy? Count me in!

ASH: It’s also by Rihito Takarai (of Ten Count fame) so I’m very curious to see how this series develops. If nothing else, the artwork should be great.

SEAN: Manga based on an unlicensed light novel, part one: the 10th volume of High School DxD.

Manga based on an unlicensed light novel, part two: the 8th and final volume of How to Raise a Boring Girlfriend.

After a year’s hiatus, the Kagerou Daze manga picks up again with Vol. 7, and should be arriving more regularly from now on. For light novel fans, the story here is different from the LN (and indeed the Mekakucity Actors anime.)

A 5th Kiniro Mosaic gives you vague yuri galore.

If you liked the idea of Magical Girls dying tragically but hate prose… well, you know. Magical Girl Raising Project, now in manga form.

The 11th Melancholy of Suzumiya Haruhi-chan is the last, which I’m pretty sure means there are no current ongoing projects for this franchise, be it anime, manga, spinoff manga, spinoff anime, or the original novels. We should take off our hats and mourn the end of an era.

My Youth Romantic Comedy Is Wrong as I Expected gets a 7th manga volume, though I’m not sure which novel volume it’s adapting.

No Matter How Much I… sigh. WataMote gives us an 11th volume. Sorry, I’m exhausted.

Of the Red, the Light and the Ayakashi ends with its 9th volume, though I believe there is a Volume 10 with side/after stories.

ASH: Another series that I’ve been enjoying but need to catch up on!

MICHELLE: Aha! I had been thinking it was complete in 9, and then recently noticed there’s actually a tenth. Nice to have an explanation for that!

SEAN: One Week Friends is a Gangan Joker title about a cute friendship and the amnesia that threatens to tear it apart.

Re: Zero finishes its adaptation of the 2nd arc with the 4th A Week at the Mansion volume.

Rose Guns Days has a 2nd volume of its 3rd arc.

School-Live! does not come to an end with this 9th volume per se, but I think the series is on hiatus right now, so this may be the last for some time.

And a 3rd Smokin’ Parade arrives as well.

I enjoyed the first novel of So I’m a Spider, So What?, though am curious as to how a book that’s half internal dialogue will translate to manga. We’ll see with this first manga volume.

Strike the Blood’s manga has a Vol. 9, which, like the light novels, has Yukina and only Yukina on each cover.

Sword Art Online has the manga adaptation of the Calibur arc complete in one volume. It’s a great arc if you like the supporting cast, who all play a role – for the last time to date, in fact.

If you feel that yokai manga have gotten too serious lately, you should enjoy A Terrified Teacher at Ghoul School, a GFantasy title that is terminally ridiculous.

ASH: Yokai comedy, you say? Count me in!

Umineko When They Cry begins its 7th arc, Requiem of the Golden Witch. Battler is nowhere to be found. Nor is Beatrice. Instead meet Kinzo’s heir Lion Ushiromiya. Oh, did I mention this first omnibus is 826 pages?

Lastly (yes, I promise, we are at the end), there’s a 7th omnibus of Yowamushi Pedal, which should be SUPER EXCITING.

MICHELLE: Yay!

ASH: I know I’m excited!

SEAN: (falls over) So are you getting everything on this list, or just most of it?

By: Sean Gaffney

0 notes