#artie shaw and his orchestra

Text

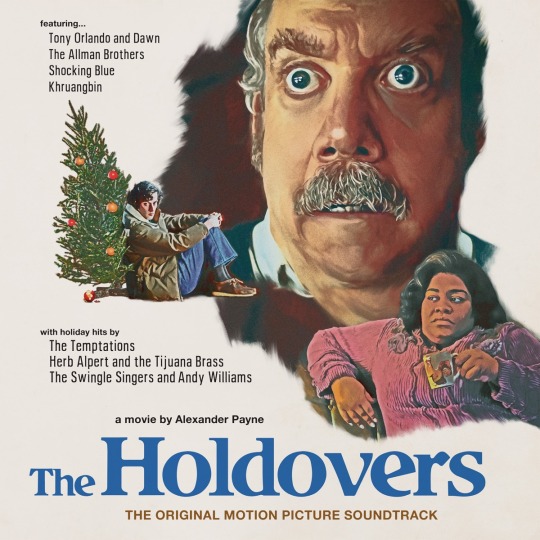

On The Jukebox: "The Holdovers (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)"

Track listing:

Damien Jurado - "Silver Joy"

Shocking Blue - "Venus"

The Chamber Brothers - "The Time Has Come Today"

Mark Orton - "Candlepin Bowling"

Mark Orton - "Primal Architecture"

Labi Siffre - "Crying, Laughing, Loving, Lying"

The Allman Brothers Band - "In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed"

Tony Orlando & Dawn - "Knock Three Times"

Artie Shaw & His Orchestra - "When Winter Comes"

Mark Orton - "Drive To Boston"

Mark Orton - "Nursing Home"

The Swingle Singers - "Medley: Deck The Halls With Boughs Of Holly/What Child Is This?"

The Temptations - "Silent Night"

Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass - "Jingle Bells"

Mark Orton - "It's Christmas!"

The Trapp Family Singers - "Carol Of The Drum (Little Drummer Boy)"

The Swingle Singers - "White Christmas"

Andy Williams - "The Most Wonderful Time Of The Year"

Cat Stevens - "The Wind"

Khruangbin - "A Calf Born In Winter"

Mark Orton - "The Glove/Now He's History/ 5/4 For Constantine"

Mark Orton - "A Girl In Two/Back To Barton"

Mark Orton - "Danny/The Glove/Let's Make The Best Of It"

Mark Orton - "See Ya/Into The Unknown"

#the holdovers#damien jurado#shocking blue#the chamber brothers#mark orton#labi siffre#the allman brothers band#tony orlando and dawn#artie shaw and his orchestra#the swingle singers#the temptations#herb alpert and the tijuana brass#the trapp family singers#andy williams#cat stevens#khruangbin

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

My Fantasy - Artie Shaw and His Orchestra with Pauline Byrne

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art Shaw and His Orchestra - Begin the Beguine (1938)

Cole Porter

from: "Indian Love Call" / "Begin the Beguine"

10" Shellac | 78 RPM

Swing | Big Band

JukeHostUK

(left click = play)

(320kbps)

Personnel:

Artie Shaw: Clarinet | Band Leader

John Best: First Trumpet

Trumpets:

Chuck Peterson

Claude Bowen

George Arus: First Trombone

Trombones:

Harry Rodgers

Russell Brown

Les Robinson: First Alto Saxophone

Hank Freeman: Alto Saxophone

Tony Pastor: Tenor Saxophone

Ronnie Perry: Tenor Saxophone

Les Burness: Piano

Al Avola: Guitar

Sid Weiss: Bass

Cliff Leeman: Drums

Arranged by Jerry Gray (Generoso Graziano)

Recorded:

@ RCA's Victor’s Gramercy Recording Studio | Studio #2

on East 24th Street

in New York City, New York USA

on July 24, 1938

Released:

on August 17, 1938

Bluebird Records

#Art Shaw and His Orchestra#Artie Shaw and His Orchestra#Swing#Big Band#Cole Porter#Begin the Beguine#Bluebird Records#Jerry Gray#Generoso Graziano#1930's

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's a little fanmix for marinating in your feelings about these two...

Contains:

Some newer songs, some older songs- including ones from their era

Themes of pining, unrequited feelings, semi-requited feelings, jealousy

Track List Below:

Soar (Main Title Theme from 'Masters of the Air') - Blake Neely

I've Got You Under My Skin - Frank Sinatra

I'm With You - Vance Joy

Can't Take My Eyes Off You - Frankie Valli

Disco - Surf Curse

I Only Want to Be With You - Dusty Springfield

Reach Out I'll Be There - Four Tops

Blue Skies - Frank Sinatra, Tommy Dorsey Orchestra

Guilty - Al Bowlly, Ray Noble & His Orchestra

Real Love Baby - Father John Misty

My Buddy - Harry James, Frank Sinatra

My Dearest Darling - Etta James

Any Old Time - Artie Shaw, Billie Holiday

These Arms of Mine - Otis Redding

Fallingforyou - The 1975

Crazy He Calls Me - Billie Holiday

Affection - Cigarettes After Sex

Once More to See You - Mitski

Everything in You - Adventure Time, Half Shy

If I Had You - Margaret Whiting

Over My Head - Fleetwood Mac

Pale Blue Eyes - The Velvet Underground

Somethin' Stupid - Frank Sinatra, Nancy Sinatra

Feather - X Ambassadors

Maps - Yeah Yeah Yeahs

I Wanna Be Yours - Arctic Monkeys

If You Were Mine - Etta Jones

Dionne - The Japanese House, Justin Vernon

There I Go - Vaughn Monroe

Baby I Need Your Loving - Four Tops

So Help Me - Mildred Bailey

I Look at You - Johnny Mathis

Jolene - Dolly Parton

Darn That Dream - Benny Goodman, Mildred Bailey

What Am I Here For - Jade Bird

My Heart Keeps Cryin' - Dorothy Lamour

Standing In The Shadows of Love - Four Tops

All I Could Do Was Cry - Etta James

Long Long Time - Linda Ronstadt

Going Home (End Titles from 'Masters of the Air') - Blake Neely

#buck x bucky#bucky x buck#gale cleven#buck cleven#john egan#bucky egan#masters of the air#mota#hbo war#Spotify#mine#clegan#mine: fanmix

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

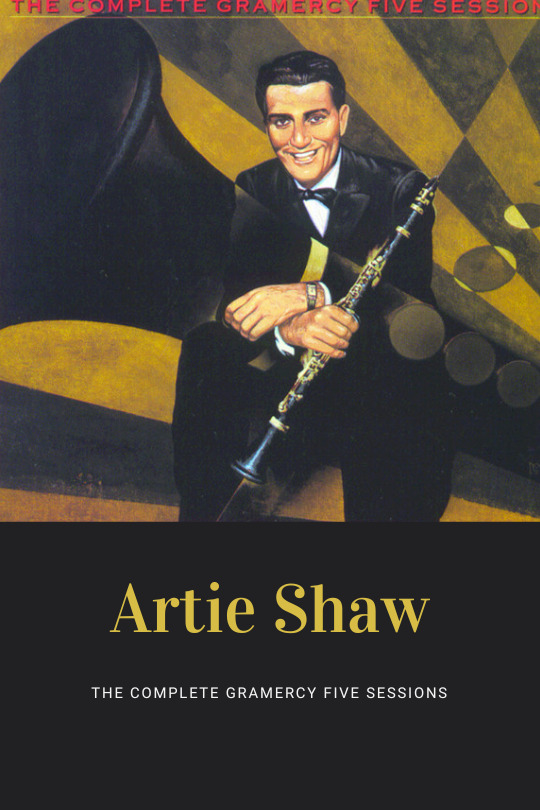

Artie Shaw – The Complete Gramercy Five Sessions

“Many swing big-band leaders featured small groups out of their orchestra as added attractions, particularly Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey with his Clambake Seven, and Bob Crosby’s Bobcats. In contrast, Artie Shaw recorded relatively few sides with his Gramercy Five. His original unit from 1940 found the great pianist Johnny Guarnieri playing harpsichord exclusively and matched Shaw’s clarinet with trumpeter Billy Butterfield. Their eight recordings include “My Blue Heaven,” “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” and a million-seller, “Summit Ridge Drive.” The remainder of this CD is from 1945 and features Shaw, trumpeter Roy Eldridge, and the two young modernists, pianist Dodo Marmarosa (on piano) and guitarist Barney Kessel. Shaw would lead a few other Gramercy Fives in the future, but these are his two most famous. The music is consistently brilliant with every note counting.” – Scott Yanow/AllMusic.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

At The Christmas Ball: A Vintage Xmas Anthology

01 - At The Christmas Ball - Bessie Smith (1925)

02 - Santa Claus, Bring My Man Back To Me - Ozie Ware (1928)

03 - Papa Ain't No Santa Claus - Butterbeans & Susie (1930)

04 - It's Winter Again - Isham Jones & His Orchestra (1932)

05 - Jingle Bells - Benny Goodman & His Orchestra (1935)

06 - There's Frost On The Moon - Artie Shaw & His Strings (1936)

07 - I've Got My Love To Keep Me Warm - Mildred Bailey (1937)

08 - Christmas Morning The Rum Had Me Yawning - Lord Beginner (1939)

09 - Winter Weather - Fats Waller & His Rhythm (1941)

10 - Santa Claus Is Coming To Town - Bing Crosby & The Andrews Sisters (1943)

11 - Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas - Judy Garland (1944)

12 - Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! - Connee Boswell (1945)

13 - Boogie Woogie Santa Claus - Mabel Scott (1948)

14 - Baby, It's Cold Outside - Pearl Bailey & Hot Lips Page (1949)

15 - All I Want For Christmas - Nat King Cole Trio (1949)

16 - What Are You Doing New Year's Eve? - The Orioles (1949)

17 - Midnight Sleighride - Sauter-Finegan Orchestra (1952)

18 - Silent Night - Dinah Washington (1953)

19 - White Christmas - The Drifters (1954)

20 - Rudolph The Red-Nosed Reindeer - The Cadillacs (1956)

21 - Warm December - Julie London (1956)

22 - Love Turns Winter To Spring - June Christy (1957)

23 - The Secret Of Christmas - Ella Fitzgerald (1959)

24 - The Christmas Song - Carmen McRae (1961)

25 - A Christmas Surprise - Lena Horne (1965)

26 - Santa Was Here - Lorez Alexandria (1968)

Download: flac / mp3

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

On October 7, 1940, Artie Shaw and his Orchestra recorded Hoagy Carmichael’s “Stardust” for RCA Victor.

youtube

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made Spotify playlists for a couple of Sing characters that didn’t get one! (Song lists are under the cut) ↓

And I made a new Buster playlist! Since he has TWO playlists from the first and second movie, I combined them into one and added some showtunes, some upbeat jazzy stuff, and a few songs that gives off Buster vibes ♡ (sorry it’s so long, he had a lot of music! Mostly oldies but goodies ♪)

♘ Eddie Noodleman ♘

✿ Miss Crawly ✿

⭐︎ Buster Moon ⭐︎

EDDIE:

8TEEN (Khalid)

Moonshadow (Cat Stevens)

Let’s Go Surfing (The Drums)

Ukulele and Chill (Cody G)

Sunflower (Post Malone, Swae Lee)

Ventura Highway (Paco Versailles)

Love Your Days (Cherokee)

Swept Away (Vanilla)

Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go (Wham!)

No Rain (Blind Melon)

California (from The O.C.)

Days Like These (Lakey Inspired)

Dream With You - Bosq Remix (Jeffrey Paradise)

Young Folks (Peter Bjorn and John)

Tropical Heartache (Poolside)

California Sunset (Poolside)

Weather (Ralph)

Inbetween Days (The Cure)

End of the Line (Traveling Wilburys)

Pink Sky (Bay Ledges)

Australia (The Shins)

Me and Julio Down By The Schoolyard (Paul Simon)

Baroque Hoedown (Perrey and Kingsley)

MISS CRAWLY:

Lagoon (Havana Swim Club)

You Make Me Feel So Young (Frank Sinatra)

What A Little Moonlight Can Do (Billy Holiday, Teddy Wilson)

Chop Suey! (System Of A Down)

April Showers (Proleter)

Frenesi (Artie Shaw)

Come Fly With Me (Frank Sinatra)

When I’m Sixty Four (The Beatles)

Shooby Shooby Do Yah! (Mocean Worker, Steven Bernstein)

C’est Magnifique (Kay Starr)

Blinuet (Zoot Sims)

The Last Time I Saw Paris (Vaughn Monroe)

Them from New York, New York (Frank Sinatra)

Sweet Happy Life (Peggy Lee)

Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da (The Beatles)

きらきらキラー (Kyary Pamyu Pamyu)

BUSTER MOON:

Flirty Cha Cha (The Daniel Pemberton TV Orchestra)

Safe And Sound (Capital Cities)

Don’t Rain On My Parade (Barbra Streisand)

There’s No Business Like Show Business (Harry Connick, Jr.)

Gimme Some Lovin’ (The Spencer David Group)

My Type (Saint Motel)

Walking On A Dream (Empire of the Sun)

The Showman (Little More Better) (U2)

Blinuet (Zoot Sims)

Come to Me (Koop, Yukimi Nagano)

Cake By The Ocean (DNCE)

Dream A Little Dream Of Me (Teddy Wilson)

Over and Over (Session Victim)

Soulful Strut (Horst Jankowski and his Studio Orchestra)

Dancing in the Moonlight (Toploader)

A Happy Song (Victory)

Call Me Maybe (Carly Rae Jepsen)

Lovely Day (Bill Withers)

End of the Line (Traveling Wilburys)

Seasons of Love (Rent the Musical)

Times Are Hard for Dreamers (Amelie the Musical)

Keep Your Head Up (Andy Grammer)

Hang On Little Tomato (Pink Martini)

Smile (Nat King Cole)

When You’re Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With You) (Louis Armstrong)

My Song (Labi Siffre)

Wouldn’t It Be Nice (The Beach Boys)

Mr. Blue Sky (Electric Light Orchestra)

Faith (Stevie Wonder, Ariana Grande from Sing)

I Got You (I Feel Good) (James Brown & The Famous Flames)

The Wind (Cat Stevens)

Hallelujah (Tori Kelly from Sing)

I’m A Believer (The Monkees)

Faith (George Michael)

You’re All I’ve Got Tonight (The Cars)

Keep It Comin’ Love (KC & The Sunshine Band)

Happy (Pharrell Williams)

Sing (Ed Sheeran)

Ain’t No Mountain High Enough (Marvin Gaye, Tammi Terrell)

Sing a Song (Earth, Wind & Fire)

Your Song (Elton John)

Golden Slumbers (The Beatles)

Goodbye Yellow Brick Road (Elton John)

Listen to the Music (The Doobie Brothers)

I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing (The New Seekers)

Saturday (Twenty One Pilots)

Someone In The Crowd (La La Land soundtrack)

The Blue Room (Zoot Sims Quartet)

Turandot, SC 91, Act III: Nessun Dorma! (Giacomo Puccini)

Viva La Vida (Coldplay)

You, Me, Here, Now (Dam Swindle)

Dancin’ - Krono Remix (Aaron Smith, Luvli, Krono)

Feel the Heat (Ghosts of Venice)

Flashing Lights (Kanye West)

Beautiful People (feat. Khalid) - NOTD Remix (Ed Sheeran, Khalid, NOTD)

Get Down Tonight (KC & The Sunshine Band)

Got To Be Realm(Cheryl Lynn)

Sing a Happy Song (The O’Jays)

Do You Believe in Magic? (The Lovin’ Spoonful)

You Can’t Stop the Music (The Kinks)

Can’t Stop The Feeling! (Justin Timberlake)

Don’t Dream It’s Over (Crowded House)

Take A Chance On Me (ABBA)

The Moonbounce (Koop)

Uptown Funk (feat. Bruno Mars) (Mark Ronson, Bruno Mars)

Off White Limousine (Client Liaison)

Old 45’s (Chromeo)

Pick Up The Pieces (Average White Band)

He’s The Greatest Dancer (Sister Sledge)

You’re The Top (Jeri Southern)

Let’s Go Crazy (Prince)

Daydream Believer (The Monkees)

Don’t Stop Believin’ (Journey)

It’s Gonna Be Good (Next To Normal the musical)

#sing 2016#sing 2#buster moon#eddie noodleman#miss crawly#sing spotify playlists#music is such a huge part of these movies!#Spotify

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

shuffle your favorite playlist and post the first five songs that come up. then copy/paste this ask to your favorite mutuals <3

I have chosen my Relax playlist

I listen to it a lot to relax, when I'm at home in the evening, for cooking, for many everyday moments.

Dreaming - Lee

It's Been a Long, Long Time - Harry James and His Orchestra and Kitty Kallen

Frenesi - Artie Shaw

Coastlines - Hollow Coves

Rewrite The Stars ( Piano Instrumental) - Box of Music

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Play ▶ Halloween Mix #11 🎃👻

(intro: Oscar Brand and His Young Friends)

All Night Long — Peter Murphy

Tombstone — Suzanne Vega

Dance of the Freaks — The Raindogs with Iggy Pop

Cemetery Stomp — The Essex

Too Many Creeps — Bush Tetras

Vampire Beavers — Joe Hall and the Continental Drift

Nightmare — Artie Shaw and His Orchestra

I’d Rather Be the Devil — John Martyn

(montage: The Slithery-Dee — Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark)

(montage: Orson Welles” The War of the Worlds”)

Mars Needs Guitars — The Hoodoo Gurus

Every Day Is Halloween — Ministry

I Walked With a Zombie — Roky Erickson and the Aliens

Frankenstein (Orig.) — The New York Dolls

(public service announcement from the greater Night Vale medical community)

Cemeteries of London — Coldplay

Welcome To My Nightmare — Alice Cooper

Wicked Annabella — The Kinks

(montage: William Conrad,” The Ghost’s Song”)

The Ghost of Stephen Foster — The Squirrel Nut Zippers

The Shadow Knows — The Coasters

(montage: The Witchmaker radio spot)

Black Sabbath — Black Sabbath

(montage: Count Floyd)

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

🎶✨️when u get this u have to put 5 songs u actually listen to, publish. Then, send this ask to 10 of your favorite followers (non-negotiable, positivity is cool)🎶✨️

Anson Weeks and His Hotel Mark Hopkins Orchestra – Was That the Human Thing to Do?

Peter Frampton – (I'll Give You) Money

Artie Shaw and His Orchestra – I Poured My Heart Into a Song [voc. Helen Forrest]

Freddie King – You've Got to Love Her With a Feeling

George Jones – The Door

Thanks so much! 🤍

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Begin The Beguine - Artie Shaw and His Orchestra

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Artie Shaw & His Orchestra "Yesterdays" song by Jerome Kern & Harbach from show "Roberta" (1938)

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Long Ago and Far Away: The Last Mission of Kenny Kai-Kee

By Douglas S. Chan

(Published previously by AsianWeek newspaper in four parts, starting June 25, 2004)

Where have all the soldiers gone?

Long time passing

Where have all the soldiers gone?

Long time ago

-- Pete Seeger © 1961 Fall River Music Inc.

This year, on the 60th anniversary of the D-Day landings in Normandy, the survivors of what General Dwight D. Eisenhower called the “Crusade in Europe” against Hitler and fascism gathered across the country for what was for many of the veterans a final summer of reminiscences. Time’s winnowing of the ranks of the citizen soldiers has accelerated with each passing year. The 16 million men and women who served during the Second World War have been dying at the rate of 1,500 per day.

The surviving old soldiers and airmen of the Second World War will congregate at the reunions, many of them for the last time. They will lift a glass to “absent friends.” Others will summon again the strength and the will to journey to far-flung places of the world where they will remember and lay flowers or wreaths at gravesites or large and small monuments, some bearing the names of fallen comrades or military units who passed that way in a grievous, global conflict.

Family members, widows, and former fiancées will pause and recall the day they heard the news spread from War Department telegrams. Some may retreat to quiet rooms and listen to well-worn 78s of Artie Shaw’s orchestra punching out “Begin the Beguine,” Tommy Dorsey’s trombone playing “Getting Sentimental over You,” or a young Sinatra singing “I’ll Be Seeing You.” The worn albums of old photos and yellowed clippings will be brought out again, and hearts will turn to a time long ago and far away.

A Soldier’s Story

He was neither the first, nor the last, of the thousands of young men who flew in the skies over Europe during the terrible summer of 1944. He was a native son of California whose courage and sacrifice remained a mystery for two generations and whose name has been forgotten except by his family and the small, tightly-knit community of East Bay Chinese Americans who came of age during the Second World War.

He was, and will be forever, a beloved son, friend, classmate, boyfriend, bomber pilot, and a Chinese American original. Long forgotten except by the dwindling few who counted him as a friend of their youth, he deserved better because he was one of the best Chinese America had to offer.

His name was Kenneth Burton Kai-Kee.

Chinese Americans Go to War

Almost 50,000 Asian Americans served in the U.S. armed forces during World War II. A 1982 Veterans Survey Report by the Chinese Historical Society of America estimated the number of Chinese American military personnel ranged from 15,000 and 20,000. Since 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act had created a bachelor society with no dependents. Many single Chinese men were the first to be drafted. The first real generation of native-born Chinese American men was also called up for military service, if they had not already volunteered.

According to the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs and researchers at the Oakland Museum, 13,499 Chinese American men fought in the armed forces. Approximately 75 percent in the U.S. Army, with units such as the 3rd and 4th Infantry Divisions in Europe and the 6th, 32nd and 77th Infantry Divisions in the Pacific, and 25 percent in the Navy. Counted together, they represented 20 percent of all Chinese American men in the continental U.S. In the words of historian Iris Chang, “ethnic Chinese men gave their lives disproportionate to their presence in the country.”

In the AAF

Kenny Kai-Kee joined the Army Air Force on October 1, 1943, while war was raging in Europe. The Army Air Force (the “AAF”) was learning hard lessons about the perils of daylight “precision” bombing. Bomber pilots and crews were needed to replace staggering losses suffered in massive bombing raids against the ball-bearing factories at Schweinfurt in the German heartland.

Kenny shipped out to Europe in 1944 to join the 15th Air Force based in Foggia, Italy. Once in Europe, he started flying B-17s with his unit, the 32nd Squadron of the 301st Bomb Group (Heavy), which had shifted its flight operations to Lucera, Italy. Kenny completed his first combat mission in the summer of 1944.

The Mission

On July 26, 1944, the 301st Bomb Group, including the 32nd Squadron, was ordered to bomb a factory complex at Wiener-Neustadt, located in a suburb of Vienna. Allied intelligence had reported that the factory was manufacturing aircraft parts. The bomber crews of the 32nd based in Lucera, Italy, knew that the mission was perilous. Vienna was heavily defended by fighters and antiaircraft fire because of its status as a major industrial center for the German army.

Several days before Kenny’s last mission, the commanding officer of Kenny’s unit, the 32nd Squadron, held a briefing for all flight personnel about new German fighter tactics against bombers. The ability of the German Luftwaffe to maintain its force of operational fighter aircraft had declined. Replacing aircraft lost to age or enemy action had become increasingly difficult because of the strategic bombing campaign that was waged against German industry by the bombers of the 15th Air Force based in Italy and the 8th Air Force based in England.

As a result, the squadron’s C.O. informed his men, the Germans were only sending fighters up once a week to challenge bomber squadrons. By keeping its fighters on the ground to repair and re-arm for ten-day periods, the Germans were able to assemble combat-ready fighter groups of two to three hundred planes to shoot down American bomber formations. The new tactics had already been used against the 8th Air Force, and the bombers of Kenny’s 15th Air Force would be the next recipients of the new fighter swarms.

“For those of us at this meeting, the numbers of 200 or 300 fighters attacking seemed unreal, since most of us had seen relatively few fighters on any one mission,” wrote Tech. Sgt. Bill Brainard, the radioman on Kenny’s old B-17F. “What I had seen before on other missions was at the most six fighters, always using the standard evasive tactic of flying in at you firing their machineguns until they maneuvered away by rolling over and putting their belly armor plate up as your target.”

An Old and Slow Plane

“That was a difficult mission, as the clouds built up to the point that we could not properly bomb our target,” wrote Bob Piper, a former Army Air Force captain. Piper, who lives in Richmond, Virginia, was a B-17 Commander with the 32nd Squadron. He was the squadron leader for the raid over the Weiner-Neudorf aircraft works that included Kenny’s bomber.

As a leader of a seven-plane squadron in a 28-plane group, Piper only had incidental contact with the Chinese American second lieutenant because Piper had the responsibility to call the squadron roll on the “fateful day” as he now refers to July 26, 1944. He confirmed that Kenny had been assigned to a plane that was an older B-17F. The plane, nicknamed “Laura,” was slower, and it also did not have a chin turret of twin, forward-firing .50 machine guns mounted under its nose.

“She was pretty patched up from numerous previous missions,” wrote radioman and Tech Sgt. Bill Brainard in his memoir 50 years later, “and slower than the later models in the squadron, especially when her bomb bay doors were in the open position. Therefore, she had to fly in the rear so as not to fall back in the path of another B-17. On a bomb run this could prove to be a hazard.”

By coincidence, Bob Piper had flown the Laura on three previous missions, including a mission that bombed Vienna’s railroad yards earlier that month. On that seven-hour mission, the 15th Air Force attacked in force and encountered no fighter planes because of cloudy conditions.

On that July morning, Technical Sergeant Bill Brainard, the radioman for Kenny’s bomber, recalled rising early, eating breakfast, and attending the usual pre-mission briefing about the expected intensity of flak and the numbers of fighters that might be sent against them. After the briefing, the crews were driven in trucks out to their planes.

That day, Kenny discovered that the plane to which he had been assigned was the Laura, bearing the serial number 157, the oldest plane in the squadron. The ground crew had already mounted the plane’s load of bombs.

A “Make-up” Crew

In addition to being assigned a slow plane, Kenny’s crew for the mission was a “make-up crew.” With the exception of Bill Brainard (who knew the navigator for the day’s mission, Thomas Steed), none of the crewmen who boarded the Laura that morning had met each other prior to the mission. After a few minutes of conversation to get acquainted with each other, Kenny and his crewmates climbed on board the aging bomber.

As the Laura taxied down a runway consisting of thousands of perforated iron mats, the plane and crew bounced as the bomber’s wheels rolled over dents in the runway for a long time. Takeoffs on imperfect, mat runways were often violently accomplished as the plane gained speed. Planes with full bomb loads that could not gain the speed to lift off might be in danger of falling back to earth and blowing up.

Kenny’s plane made it off the ground that day, climbing into the sky over the Adriatic Sea and gaining altitude steadily. From his seat in the co-pilot’s position, Kenny would have seen the Swiss Alps. Sitting in the middle of the fuselage, his radioman Bill Brainard searched the sky and felt a sense of calm as the engines droned.

For all of the bombers of the 32nd Squadron, the takeoff and rendezvous into formation in the early morning of July 26, occurred without incident. Bob Piper’s plane, “Miss Tallahassee Lassee,” was the leader of a formation of seven planes assigned to the “Diamond,” the rearmost position of a four-squadron group of 28 ships. Since Kenny’s plane lacked speed, the Laura flew in the lower left position of Piper’s flight of bombers. This “coffin corner” position was considered the most dangerous place in the formation because of its vulnerability to attack from enemy fighters.

The flying conditions on the morning of July 26 consisted of towering clouds and unstable weather. However, Bob Piper, Kenny Kai-Kee, and their comrades did not know that the other bombers from the 15th Air Force would not join their flight group. The weather conditions had forced the rest of the 15th Air Force to turn back. Kenny’s group leader, however, never received the radio call to abort the mission.

The mission should never have occurred, but the planes of the 32nd Squadron still flew on and, in so doing, produced the terrible confluence of events that changed forever the life of Kenny Kai-Kee, and the start of a mystery that would endure for a half century

[end of part I]

(Second of four parts)

I’ll be seeing you

In all the old, familiar places

That this heart of mine embraces

All day through . . .

-- Lyrics and music by Irving Kahal and Sammy Fain

Kenneth B. Kai-Kee was the son of a pioneer family and a native-born, Chinese American in an era when there were few. Even his surname was an invention of the Chinese American West.

Kenny, as he was known to his friends, was a grandson of Ching Hin Kim, a legendary Chinese pioneer who had settled in Ione, California. Ching Hin Kim ran the “Kai Kee” general store that served the Chinese miners of Amador County. Grandfather Ching and his American-born wife, Mo See, had nine children, eight of whom were sons born in Ione. All the townspeople of Ione called the eight sons the “Kai-Kee Boys,” and the name stuck. The Ching family was a long way from On Doong village, Heungshan County, Guangdong province, so why not invent a new name in an adopted country? In Chinese California, the family adopted the Kai-Kee store’s name as their American moniker.

Kenny’s father, Lock Kai-Kee, was already a longtime resident of Oakland, California, when Kenny was born on October 21, 1921. Lock and his wife, Ida Margarita (a.k.a. “Rita”), worked hard and bought a home at 927 - 45th Street in north Oakland. Lock was a member of the Wa Sung Athletic Club, and his picture as the third base coach of the Wa Sung baseball team of 1931 appeared recently in the Wa Sung Community Service Club 2004 Community Directory. Lock and Rita represented rare breed of Chinese Americans who reflected a new sophistication from their youth spent in the Jazz Age of the 1920s.

“I do remember meeting Kenny’s parents whom I admired,” recalled family friend, Dolores Wong, “because they were so modern and acculturated. They were part of a group of friends who enjoyed dancing, knew how to enjoy life, wear stylish clothes, and travel.”

Swing Time at Cal

The Kai-Kee’s only son, Kenny, was a natural athlete in a family of prominent sportsmen. Kenny’s Uncle Sam played varsity football for the “Wonder Team” of 1918 at UC Berkeley. Uncle Mike played varsity baseball for Yale University in the 1920s. Another uncle, Mark Kai-Kee, earned a letter as a member of the boxing team and Stanford’s Class of 1934.

To his grade-school classmates, Kenny was an easy-going and fun kid who grew into the personable young man who is remembered today. He had little problem attracting his fair share of female attention. Dolores Wong, who entered UC Berkeley in the fall of 1938, remembered her fellow collegian, Kenny, as a likeable, social and friendly student and the old boyfriend of Phyllis Soohoo -- my mother.

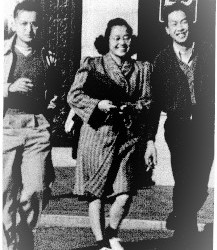

Kenny Kai-Kee (right) with Phyllis Soohoo (center) outside Sather Gate at the University of California Berkeley, 1940. (Photographer unknown from the collection of Doug Chan)

Alice (Chue) Lew, who joined the Cal gang in 1939 as a new generation of Chinese Americans started to attend college in force for the first time, recalled the good times before the war and the young adults living in the tempo of swing-time.

“In those days, all Chinese students came together. It was something we felt, close together as Chinese. He [Kenny] was really a fun-loving person. He had a great personality. I remember him as a really nice guy to be around,” recalls Alice Lew.

At Cal Berkeley, Kenny Kai-Kee had been a student-athlete on the move. He was studying accounting and “good at everything.” He was a memorable feature of the campus social scene, as he often planned the getaway trips to Santa Cruz for all of the Chinese kids. Snapshots of Kenny at Lake Lagunitas, relaxing with the gang at Cal, and walking the grounds of the World’s Fair on Treasure Island, show a relaxed, confident young man with an easy smile.

Kenny Kai-Kee (left) and Phyllis Soohoo (center) with friends at the World’s Fair on Treasure Island, July 22, 1940.

By all accounts, Kenny Kai-Kee had a bright future. One friend recalled that he had the highest I.Q. test score and always seemed to have his homework done. This left him plenty of time to enjoy the outdoors and organize his share of the swim parties at Lake Temescal and Lake Anza, the double-dates, and the big bands at big hotels such as the Palace, the Claremont and the ‘Drake. Kenny was in the middle of it. After all, he also was one of the lucky guys on campus who owned a car -- a two-seat Model A.

“[H]e was a very up beat young man with a mischievous sense of humor,” recalls Maggie Gee, herself a legendary pilot for the WASPs during World War II.

War Comes to Oakland

In 1940, the U.S. Census counted 3,201 persons of Chinese ancestry living in Oakland, California. Lock and Rita Kai-Kee must have been proud of the family’s good fortune before World War II. They had worked hard to own their house on 45th Street, and their only son, Kenny, was enrolled at UC Berkeley. He was a natural athlete who would soon earn a letter jacket for one of Cal’s varsity teams.

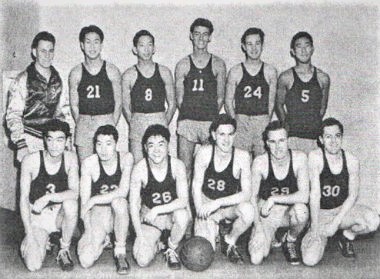

According to CalBear81 at the Cal Bears FanPost here, “Kenny enrolled at Cal in 1939, he would want to be part of a sports team. At that time, Cal sponsored basketball teams for players 145 pounds and under, and for players 130 pounds and under, in addition to the Varsity team. These teams had their own league, and even a post-season tournament, sponsored by the A.A.U. Kenny Kai-Kee played on Cal's 130-pound team throughout his years at Cal.”

Kenneth Kai-Kee playing basketball for the University of California. He is #21, standing in the back row, second from left. (Photo courtesy of the University of California Berkeley)

When the war came to America’s Chinatowns, the young men of Oakland’s Chinese community answered the call. Men such as my uncle, Clayton Soohoo, and Alfred Fong and Wilfred Eng, both of whom, as they told the Oakland Tribune last year, were inducted into the Army on the same day. The Army Air Force took 25 percent of the Army inductees, including Kenny Kai-Kee.

“I remember Kenny Kai-Kee as a student at Cal, a talented athlete, very popular, with a good sense of humor,” said retired Judge Delbert Wong who would later serve with the AAF as a bomber crewman.

On October 1, 1943, Kenny Kai-Kee entered the service of the United States Army Air Force as a pilot-trainee.

Kenny Kai-Kee behind the wheel of a jeep probably at Dyersburg Army Air Force base in 1944.

Kenny’s training did not pass without incident. AAF records indicate that he had survived a landing accident at Dyersburg AAF base in Tennessee on February 24, 1944. Kenny and the pilot of the B-17F suffered a landing gear collapse after landing.

Kenny’s uncle, Mark Kai-Kee, recalls hearing from a friend of Kenny’s that the accident occurred in part to an error by Kenny in hitting the gear switch instead of the flap switch after completing their landing roll. The oversight was understandable because Kenny and his co-pilot were distracted after having been lost, and they were excited to have found their way back to base.

In spite of receiving a reprimand for the bad landing, Kenny qualified as a bomber pilot in 1944. The stateside snapshots of him taken for the relatives back home show how easily he wore the snappy uniform and the pilot’s wings of the AAF.

“He was one of the few Asians to become a bomber pilot,” recalled fellow collegian and retired judge, Delbert Wong. Wong survived 30 missions with the AAF as a navigator with the 401st Bomb Group. “Since the pilot was the captain of the crew, there many on the selection board who thought Asians would not be good leadership material,” “Most Asians on combat air crews were navigators, bombardiers, or gunners.”

Kenny Kai-Kee, was a handsome and popular, All-American Chinese college kid who answered the call of service to his country. The only son of Lock and Rita Kai-Kee of Oakland, California, had grown into manhood with the Army Air Force.

[end of part II]

That’s the way it is in war. You win or lose, live or die -- and the difference is just an eyelash.

- Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Reminiscences (1964), p. 145

When Kenny Kai-Kee received his commission as a second lieutenant in the Army Air Force in October 1943, the tide of the Second World War in Western Europe had not yet turned against Nazi Germany. The air offensive conducted by the bombers of the AAF during daylight, in concert with the night-bombing campaign by the RAF against Germany and Italy is credited with the helping defeat the Axis powers during World War II.

The AAF paid a high price for its successes. Losses from all causes totaled 27,694 aircraft, including 8,314 heavy bombers, 1,623 medium and light bombers, and 8,841 fighters destroyed in combat.

Daylight Bombing

The casualties incurred by the strategic bombing campaign over Germany’s industrial heartland were particularly horrific. American military planners had simply assumed that the bombers “would always get through.” AAF brass had further assumed, according to military historian Tami Biddle, that “the speed of bombers such as the B-17 “Flying Fortress” and its multiple guns would enable bombers to fly in self-defending groups -- without long-range fighters to fly alongside as protective escorts.”

The daylight missions by the 8th and 15th Air Forces killed and wounded thousands of men. According to US Air Force Museum historians, total AAF battle casualties were 91,105 personnel -- 34,362 killed, 13,708 wounded, and 43,035 missing, captured or interned.

Even when long-range escort fighters using jettisonable fuel tanks were introduced in the winter and spring of 1944, the air forces of the U.S. and Germany were locked in a brutal war of attrition. Given American numerical superiority in aircraft, the resulting degradation of German industrial capacity and Luftwaffe interceptor aircraft had assured effective Allied air supremacy by the D-Day landings in June 1944.

Into Austria

The flight of the old and slow bomber, nicknamed “Laura,” took its co-pilot, Kenny Kai-Kee and his crewmates north from Italy in the midsummer of 1944. The Laura was part of a 28-plane group from the 32nd Squadron of the 301st Bomb Group *Heavy) that had flown without incident across the Alps, and into Austrian airspace on July 26, 1944. The bombers intended to rendezvous with other planes of the 15th Air Force to bomb an aircraft factory complex at Wiener-Neustadt.

Unknown to the bomber group, the 15th Air Force had cancelled the mission and recalled all bombers. The group leader’s plane, however, never received the recall order. Thus, Kenny’s plane and the other ships from the 32nd Squadron flew on toward the heavily-defended, industrial suburbs of Vienna.

“The 15th Air Force cancelled and recalled the planes,” squadron leader Piper revealed in an e-mail message to Kenny’s cousin a half-century later. “Somehow our group did not get the radio message and we continued on alone. The fighter planes were waiting for us.”

From his station in the middle of the plane’s fuselage, Kenny’s radioman, Bill Brainard, waited for the usual number signal at 11:00 a.m. from the base radio station. At 10:55 a.m., Brainard was scanning the skies out of the radio room window when he saw on the horizon dozens of contrails – the strands of vapor left by planes rushing toward the bomber formation. Brainard immediately switched on his plane intercom and called over the system to ask if the pilot had seen approaching group of planes.

“I hope they are our escort,” answered the Laura’s pilot, 2nd Lt. Leo J. McDonald, “they’re late! Everybody, keep your eyes on ‘em.”

Fighter Attack

Brainard, assuming all was in order, switched off his intercom and back to his radio to wait for the base radio signal. Feeling uneasy, Brainard switched back to his intercom to find out what was happening outside. As he did so, he heard through his headphones a gunner’s quiet remarks.

“They look like ME-109s,” a voice said matter-of-factly.

“GOD DAMN IT, THEY ARE 109s!” blared the same voice, and Brainard heard the gunners start firing their Browning .50 caliber, air-cooled machine guns.

According to squadron leader Bob Piper, approximately 50 Focke-Wulf fighters descended at once on the lumbering flight of American bombers about 50 miles south of the target. The results were horrific to the air crews who witnessed the carnage.

“They were waiting for us,” Piper recalls. “The fighters started at the back of the squadron, and worked up to the front. Planes #3 (on my right wing), 5, 6, and 7 (the three trailing ships) went down almost at once. Plane #2 (on my left wing) and #4 (trailing just behind me) were hit. We did not see any of them completely destroyed.”

During the ten-minute attack, the gunners of Piper’s ship, Miss Tallahassee Lassee, shot down eight of the FW-190s and damaged a dozen more. The aircrew of Piper’s #4 plane destroyed another nine and damaged five of the German planes.

“Twenty-millimeter cannon shells were bursting between the lead squadron and me, a hundred of them, from the rear, right in front of my face,” Piper recounted. “I remember ducking, and then remembering that my seat back included armor plate.”

A few minutes after fighting off the German fighters, Bob Piper’s bomber flew into a cloud. When his ship emerged, bombers #4 and #2 were nowhere in sight. The Miss Tallahassee Lassee was the sole survivor from its squad flew on for another 20 minutes in the clouds, dropping its bombs at random because of the thick cloud cover, avoiding flak and midair collisions with other American bombers, and rejoined the other survivors of the group for the trip back to Lucera. Piper’s plane had endured the ordeal unscathed. His #4 plane, which had returned to base after the fighter attack, was the only other ship from Piper’s Diamond.

The Laura, co-piloted by Kenny Kai-Kee, was missing.

Death Spiral

The tail-gunner on board the leading plane of the bomber group saw Kenny’s ship pull up suddenly from its lower, tail-end position to an altitude slightly higher than the lead bomber. When it could ascend no more, the Laura began to roll over and head downward.

On board the Laura, Kenny and his pilot, 2nd Lt. Leo J. MacDonald, were coping with the catastrophic damage to their ship. Machine gun or cannon fire from the Luftwaffe planes had torn into the American bomber’s wing, setting on fire its right wing tanks. The ship had started going down in a “right peel.” A ball turret gunner in another plane saw the Laura pass overhead -- on fire.

“It appeared as if the Pilot pulled it to one side to spare other ships in the formation,” Staff Sergeant Albert Bernard, Jr., reported later to the AAF. “157 was to the rear of us at five o’clock when it dove straight down, spinning as it went down.”

As Kenny and his pilot fought to regain control of their ship, the damaged bomber was seen by witnesses to level off momentarily.

“It pulled out for a moment then continued to dive,” Sgt. Bernard wrote. “When it was a 1,000 yards below us, it blew up. One chute was seen to open.”

Radioman Bill Brainard had been firing his machine gun and watching another bomber from its high-right position in the formation fly over Kenny’s plane, missing it by inches and finally going down. Brainard continued firing while clipping on the parachute that he had forgotten to wear.

Ten Minutes

At the moment when the Laura exploded, the sudden lurch of the plane slammed Brainard’s face onto the floor. Centrifugal forces pinned him there momentarily. When he could move, Brainard pulled himself into a squatting position at the bulkhead door to the bomb bay, looking forward. He could see nothing but sky; the bomb bay had blown away. From his position, Brainard saw the entire front portion of the Laura descending with its full load of bombs, its propellers still spinning. Kenny and the pilot were still strapped into the cockpit, at the controls. The nose of the bomber had blown out, blowing the bombardier out of the plane without a parachute.

The same opening in the nose allowed the navigator, Thomas J. Steed, to escape. Prior to the explosion, Steed became the last living person to hear Kenny’s voice.

“Is everything all right, navigator?” Kenny asked. A second later, the plane was spinning downward, and Shallcross was trapped at the escape hatch. At about an altitude of 1,000 feet, Shallcross was able to pull himself out of the plane’s nose and deploy his parachute about 500 feet above the ground. As the Laura fell to earth, Shallcross realized that Kenny and his remaining crewmates were either dead or dying from enemy gunfire or from the centrifugal forces exerted on the plane’s contents as it plunged toward earth.

In the meantime, a very scared Bill Brainard was looking aft. The concussion from the onboard explosion had also blown out the tail section of the plane. Unknown to him at the time, both waist gunners and the tail gunner had been able to parachute safely. Seeing nothing but daylight at both ends of his part of the fuselage, Brainard jumped out from his section of the shattered aircraft. He delayed opening his parachute in order to avoid having the falling wreckage rip his chute’s canopy. As his chute deployed, Brainard was pulled up and saw the section of plane from which he had just exited hurl past him to the ground.

Brainard landed safely in the Austrian countryside at 11:05 a.m. As he looked up, he saw the rest of the bomber group continue on its way to the target. He also saw fighter activity in the sky and realized that the American escort fighters had apparently shown up -- too late for Kenny and the Laura.

The entire air battle from the time Brainard first spotted the German fighters had lasted a mere ten minutes.

As he gathered in his chute, Brainard could hear numerous gun shots. He had landed near the crash site of the Laura. The front-section of the bomber had slammed into the ground and was burning. The bomber’s onboard ammunition was “cooking off” in the ensuing fire. As he listened to the sounds, he heard and felt the massive explosion of a 500 lb. bomb detonating.

After evading contact with local search parties and hiding all night, Brainard was discovered and befriended by an Austrian farmer and his wife. They led Brainard to the Laura’s crash site on the following day.

The Laura had been flattened by the force of its impact with the ground. The corpse of the ball turret gunner was visible in the plane’s fuselage. He had not been able to winch himself out of gun position and jump out of the plane in time. Little remained of the two pilots. The bomber’s gas tanks had ruptured, setting off a fire that had consumed the front section and wings of the aircraft. The 500 lb. bombs had detonated and left a ten-foot hole near the wreckage, scattering human remains and more debris around the crash site. Twenty-four hours later, the rim of the blast crater was still smoking.

Kenny Kai-Kee was not coming home.

[end of part III]

These endured all and gave all that justice among nations might prevail and that mankind might enjoy freedom and inherit peace.

– Author unknown, Normandy Chapel (inscription on exterior of the lintel of the chapel).

In a corner of San Francisco’s Chinatown, families and veterans congregated in February 2004 to celebrate the restoration of one of the few monuments devoted to Asian American veterans. The recently restored plaque in St. Mary’s Square commemorates the Bay Area Chinese American service personnel killed in the line of duty during World Wars I and II.

A reading of the names on the plaque will not disclose the name of 2nd Lt. Kenneth B. Kai-Kee, of the 32nd Squadron, 301st Bomb Group (Heavy), 15th Air Force. The omission is not surprising because the disappearance of Kenny Kai-Kee sixty years ago was a mystery to all except a few family members. His name has rarely, if ever, appeared in the lists of Chinese Americans who died in service to the United States since the time of the Civil War to the present. In fact, the circumstances of his passing remained a mystery even after the war. When the War Department published its World War II Honor List of Dead and Missing for the State of California in 1946, the entry beside his misspelled name merely stated a “finding of death.”

His name, however, mattered to the young woman who would become my mother and to the small community of native-born Chinese Americans who grew up in Oakland Chinatown or attended UC Berkeley before the war.

Survivors

As the sole witness to Kenny’s death on July 26, 1944, Sgt. Bill Brainard spent the rest of the war at Stalag Luft IV. Five decades later, he would discover by reading in an ex-POW newsletter that a fifth crewman had miraculously survived the downing of the Laura.

“We lost 12 planes from our 28-plane Group,” wrote Bob Piper, the leader of Kenny’s bomber squadron. Piper and the survivors from the 32nd Squadron were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for their efforts on the costly mission over Wiener-Neustadt, Austria.

“You and your family have my sympathies,” Piper wrote to one cousin who was researching Kenny’s fate years later. “I thank God that I have survived to tell some of the story.”

Dreams Deferred

Kenny was one of the bright members of the first wave of Chinese Americans to enter the university. Many of the students who entered Cal before the war had grown up in Chinese communities, lived through the Depression, and were graduated from American high schools. On the eve of war, they were poised to strive for genuinely American futures beyond the confines of the ethnic enclaves that had circumscribed their parents’ lives.

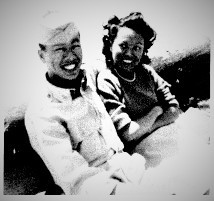

“We were going to get married in ‘42-‘43,” said Jane Lim Ligh, who became engaged to Kenny while a student at Cal. “Kenny had it all set up. We wanted to get married all through Cal.” Unfortunately, Jane fell ill in 1943, and her subsequent hospitalization caused the couple to postpone their plans. By the time she had recovered, however, Kenny had been shipped overseas.

Kenny Kai-Kee and Jane Lim Light, c. 1944.

Homefront Sorrow

As the terrible summer of 1944 drew to a close, word of the shoot-down of Kenny’s plane spread quickly among his college mates and the tight-knit Oakland Chinese community. The bad news traveled quickly around the world, reaching Mark Kai-Kee, Kenny’s uncle, in India, where he was training Chinese troops in the art of firing 4.2 inch-mortars for General Stillwell.

“The family was hit very hard,” recalled Alice Lew, “the mother especially, Kenny being an only son.”

Sadly, the details of Kenny’s death, and the series of misfortunes on one horrible day, remained largely unknown to family and friends.

“I returned home in July 1944 to learn that Kenny was missing,” the future and now retired Judge Delbert Wong recalled. Wong, a veteran of the 401st Bomb Group, had finished his 30th mission over Europe one week before D-Day. “When I was in the Bay Area, I visited Janie Lim, who read me Kenny’s letter to her after his first mission, in which he said, ‘One finished, and 29 to go.’”

As the days stretched into months, and it became clear that Kenny was not going to return. Lock and Rita Kai-Kee were devastated and lonesome with their only son gone. For a time, Jane could not visit them. She had been hospitalized for a year with a serious illness, and there was the denial born of a parent’s grief.

“Also, it was hard to go there,” Jane remembered. “They thought he was still alive, but we all knew otherwise.”

Although he was later classified as killed in action, Lock and Rita probably never knew all of the facts relating to their son’s death.

Coming Home

Kenny’s remains had been interred initially in a distant plot. The German records recorded a burial first on July 27, 1944, in the cemetery of St. Jakob i. Walde, Austria. More than five years later, Lock and Rita were notified that Kenny’s remains were coming “home” to be re-interred at the Jefferson National Cemetery Barracks. His parents traveled back to St. Louis, Missouri, to witness the re-interment, which occurred on May 15, 1950.

Kenneth Kai-Kee is buried together with two of his crew mates at a military cemetery in St. Louis.

Kenny’s fiancée, Jane, recalled her brother telling her “you gotta join the living; you gotta face the truth.” Kenny was not going to walk through the door again -- ever. She later married. In the decades that followed, she and her husband would regularly get together with Kenny’s parents to talk of the old times and the people Kenny had left behind.

Marcia Kai-Kee, a younger cousin of Kenny, remembered the day when, after Lock Kai-Kee’s death, she and other family members entered the room at the house on 45th Street that had been Kenny’s bedroom. The closet containing Kenny’s clothes had not been disturbed for years. His uniform, medals, and letter jacket from Cal remained where they had been stored in 1945, as if Lock and Rita expected Kenny to come home any day.

My mother, Phyllis Soohoo, was a compulsive archivist. She kept all of the half-dozen photos of her and her old boyfriend, Kenny Kai-Kee, and sent a Christmas card to Lock and Rita every year thereafter. Years later, when her own family went out for dinner in Oakland, she would meet and greet Kenny’s parents on the sidewalks of Chinatown as the old-time families usually encountered each other going to or from dinners at the old Silver Dragon.

No one can recall if Lock and Rita Kai-Kee ever revisited their son’s lonely grave in St. Louis, so far from family, friends and loved ones. If my mother knew of the location of Kenny’s grave when a cross-country motor trip with her family drove her through St. Louis in the summer of 1964, she never mentioned it.

My late mother would probably deny it, but a close observation would have detected the fleeting, faraway look whenever she talked about Kenny or if his name was mentioned in conversation. She, Jane Lim and millions of other Americans knew first-hand not only the young men who never returned from the great global conflagration of the 1940s, but the loss, grief, and the waste of war.

Rita carried the bitterness of her loss and the cruelty of war’s cost until her death in August 1983. Lock died seven months later.

Honor and Remembrance

If the task of reclaiming the history of Chinese America must begin anew with each generation, then the stories of gallantry and sacrifice should also be told again, if only to call on new generations, native and immigrant, to engage in a singular act of faith. To retell such stories to reaffirm a hope that the mere utterance of the names will sustain the memories of the lives, the valor, and the sacrifices of the Chinese Americans who also served. Such is the heavy burden on ethnic historians and our storytellers to remember the community’s forgotten men in unforgettable ways.

Thankfully, many of Kenny’s generation of fighting men returned to become community leaders in their own ways. Without the retelling of their stories, we would never have known about Army Air Force veterans from all over California who flew in B-17s, such as Oakland’s own Sgt. Thomas Fong; 1st Lt. Fred Gong, recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross; pilot and 1st Lt. Victor Schoon; and 1st Lt. (and later judge) James Sing Yip. They deserve to be honored and remembered.

The loss of Kenny Kai-Kee, the only son of a pioneering family, was doubly bitter because he exemplified the first All-American generation of Chinese. He would never realize that the Second World War proved to be a watershed event for Chinese American youth. The war coincided with the making, and spurred the rise, of the first Chinese American middle class. As the image and condition of the Chinese in America changed, so did its economic opportunities. By 1943 -- the year the Exclusion Act was repealed -- 15 percent of the shipyard workers on San Francisco Bay were Chinese.

The young men and boys who flew in the B-17s of the 8th and 15th Air Forces came home to a Chinese America not fully free of the strictures of white racism, but well on its way to equal rights for Chinese Americans, freed from the Chinese Exclusion Act. During the war, Chinese American men and women were working real jobs for the first time in the world’s only industrial behemoth and gaining new respect from their fellow citizens.

Kenny would have heard the laughter of unprecedented numbers of children in the Nation’s Chinatowns. He would have seen his buddies buying houses in the desegregating neighborhoods, resuming college careers on the G.I. Bill, and wading into the social and cultural mainstream of postwar America.

We will never know what Kenny could have accomplished had he lived. Had he stayed in Oakland, he probably would have married the love of his short life, raised a family, and grown old. We would have seen him as another 80-year-old senior citizen; he would have stood alongside my uncle Clayton Soohoo, another AAF veteran, serving up fifty years’ worth of his easy banter along the stacks of pancakes at the Wa Sung Club’s annual Easter breakfast. As a member of one of Chinese America’s greatest generations, he would have made his own contribution.

Instead, we are left only with the perplexing example of the incredible selflessness of Kenny and the thousands of other young men who never made it back home. Such selflessness demands that we ponder the meaning of his brief life and how in our time, beyond the words and through our own deeds, we as Americans can make his death meaningful and us worthy of such a sacrifice.

Wayback links to web versions of Parts 2 and 3:

https://web.archive.org/web/20060830170206/http://news.asianweek.com/news/view_article.html?article_id=019c51686f3a4380e8c1ac8c572b8b96

https://web.archive.org/web/20061021050227/http://news.asianweek.com/news/view_article.html?article_id=232bcbea8f0b8baeb40352043d91c9e2

#Kenneth Kai-Kee#15th Air Force#Chinese Americans in WW II#Mark Kai-Kee#Delbert Wong#Oakland Chinatown#Bill Brainard#Bob Piper#301st Bomb Group#32nd Bomb Squadron#Kenny Kai-Kee

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Between 1917 and 1943, the music scene experienced significant shifts, including the rise of jazz, swing, and big band music. Here's a list of some of the most popular songs from that era, encompassing a mix of genres that were prevalent during this period:

1. **"Darktown Strutters' Ball"** by Original Dixieland Jazz Band (1917): An early jazz classic that represents the genre's emergence.

2. **"Dardanella"** by Ben Selvin and His Orchestra (1919): A hit song that dominated the early 1920s.

3. **"Swanee"** by Al Jolson (1919): A signature tune for Al Jolson and an enduring classic.

4. **"St. Louis Blues"** by Bessie Smith (1925): A blues standard with strong influence from jazz.

5. **"Rhapsody in Blue"** by George Gershwin (1924): A jazz-influenced orchestral piece that became iconic.

6. **"Ain't Misbehavin'"** by Fats Waller (1929): A classic jazz piece with enduring popularity.

7. **"Body and Soul"** by Coleman Hawkins (1939): A jazz ballad showcasing Hawkins' saxophone mastery.

8. **"In the Mood"** by Glenn Miller (1939): One of the most iconic big band swing songs.

9. **"Begin the Beguine"** by Artie Shaw (1938): A big band hit with a Latin rhythm.

10. **"Moonlight Serenade"** by Glenn Miller (1939): Another big band classic by Glenn Miller.

11. **"Sing, Sing, Sing (With a Swing)"** by Benny Goodman (1937): A high-energy swing song that's a staple of the big band era.

12. **"Thanks for the Memory"** by Bob Hope and Shirley Ross (1938): A popular standard and Oscar-winning song.

13. **"Chattanooga Choo Choo"** by Glenn Miller (1941): A catchy swing tune with train imagery.

14. **"I'll Be Seeing You"** by Billie Holiday (1944): A sentimental ballad with deep emotional resonance.

15. **"Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy"** by The Andrews Sisters (1941): A lively, patriotic swing song.

16. **"White Christmas"** by Bing Crosby (1942): A timeless holiday classic that gained immense popularity during WWII.

17. **"Don't Sit Under the Apple Tree"** by The Andrews Sisters (1942): A fun, romantic swing tune.

18. **"I've Got a Gal in Kalamazoo"** by Glenn Miller (1942): Another hit song by Glenn Miller with a playful tone.

19. **"Sentimental Journey"** by Les Brown and Doris Day (1944): A sentimental and enduring song.

20. **"Stormy Weather"** by Lena Horne (1941): A soulful ballad with rich emotional depth.

These songs reflect the diverse musical landscape from 1917 to 1943, covering jazz, big band, swing, and popular standards.

0 notes

Text

2/8 おはようございます。 Artie Shaw / And His Orchestra LN3150 等更新しました。

弘田三枝子 / The Wonderful World Of Mieko Hirota SW-7062Helen Merrill / Affinity HL-5017Joy Bryan / Make The Man Love Me M3604Duke Ellington / in a Mellotone Lpm1364Artie Shaw / And His Orchestra LN3150Artie Shaw / Moonglow Lpm1244Charlie Burrelli and His Trio / Man on First Bass ss-1001Al Caiola / Percussion Espanol s2006Dick Morgan / See What I Mean rlp347John Coltrane / The First Trane…

View On WordPress

0 notes