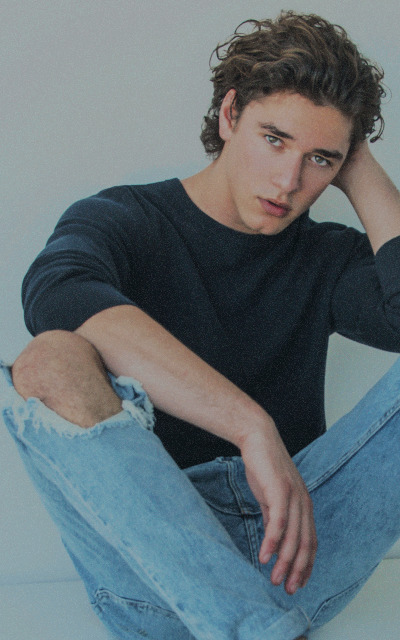

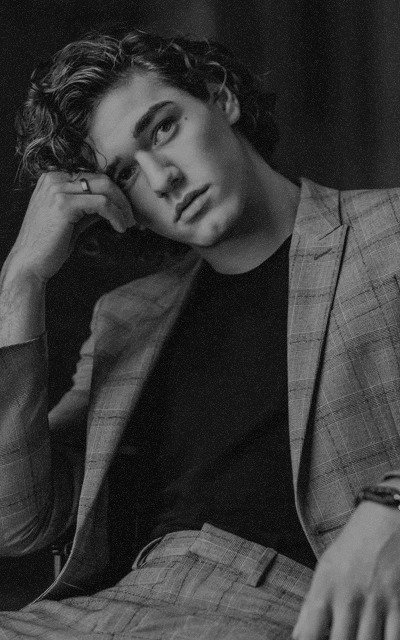

#belmont cameli avatars

Text

@viralvava

~

Existence was a lonely affair, for Death. He was created at the beginning of time, only bound to collect departed souls and to the avatar of his Creator. He was feared, he obeyed: that was the beginning and the end, and Death knew no more, and simply did what he was made for, without anything else touching his mind.

Master Bernhard was an excellent ally, when it came to providing souls: his little, petty games always ended with one or two souls for Death to collect. He took no joy in separating parents from children, or betrothed from one another, but it was the purpose of his existence. That, however, did not make for enjoyable company. Master Bernhard was far too self-conceited to strike a conversation with whom he looked as a servant. It was alright with Death, as he himself was not one to waste words for those who did not deserve them.

Then, one day, Master Cronqvist completed the Crimson Stone, and Death bowed to the newborn vampire not without curiosity. What sort of Lord would he become? One hungry for power? One who longed for solitude? A benefactor for his subjects? It was new: and for the first time in centuries, the spark of excitement ignited in Death's ribcage.

What Master Cronqvist, and then Dracula, ended up being, was a friend.

Death was reticent in borrowing such paltry human terms, but he figured that it fit their situation. Master Dracula spent his first centuries as a vampire in relative peace, building up power, only feeding when necessary - a far cry from Death's former master - and striking conversations with him. He was eager to know more about the world, and he relied on Death's ancestral knowledge and wisdom, to give him advice on how to rule on the land, or simply because for the longest time, the two of them were the only being in Master Dracula's own castle. It suit Death just fine: his Master made for enjoyable company.

But Master Dracula seemed to be a more magnanimous vampire than his predecessor, because he eventually fell in love. Death took care of his Master's human wife, and his hybrid son when he came to light. For reasons he could not explain, Death kept feeling a twinge of repulsion at the sight of Master Dracula smiling at the woman, but he kept quiet, for his Master's joy is what he existed for. And so, for the first time since he could remember, he regretted taking a human soul - the one who plunged his Master into despair. Still, Death never left Master Dracula's side, and collected all the souls of the victim of his grief, aware that for the world he was nothing but a monster, but for Death, he was but a lonely man in need of comfort.

And then the Belmont slew his Master, with the same weapon that had slashed Death centuries prior.

How could have Death failed him? The vampire's soul returned to the abyss, far where Death couldn't reach him; but it still beckoned to him, his closest servant, to be brought back.

He could not allow it. He worked tirelessly on a plan to revive the Lord. He had to, he had to bring Master Dracula back to the human world, where he belonged...!

The useless Devil Forgemasters frustrated all of his efforts.

No matter what Death did, Master Dracula spent more time dead than alive. And Death worked alone, collecting souls, waiting until the time was right... missing him.

The notion was laughable. Master Dracula was a mere child, compared to the eons Death had existed for. He served him, because he had to, but surely he couldn't have left an impact that strong in a few centuries.

No, he eventually was forced to accept. He was not only bound by duty. What pushed him to try everything in his power, manipulating unwitting humans, striking alliances with the odd Belmonts, slaying wayward vampires who dared to take his Lord's place, was the joy that resonated in his core when his Master rose back from his ashes. Every time he was called back by the greed of humans, Master Dracula was more wan, his eyes more sunken, his fangs longer and sharper; but he always greeted Death with a smile, as if no time ever passed for him.

But it passed for Death. Even an ancestral being such as him could feel the weight of a mere century, if spent alone without the only creature he could call a friend.

The sight of the young human clad in white was a blow to his ribcage. Death will never, ever forgive the Belmont clan, who forced him to fight that weak, pitiful, haughty boy who no longer had any memories of his old confidant.

#castlevania#akumajou dracula#beev's writing#prompt meme#death castlevania#deathula#i have four wips laying around and a half dozen ancient prompts still#why not working on something else entirely :)

19 notes

·

View notes

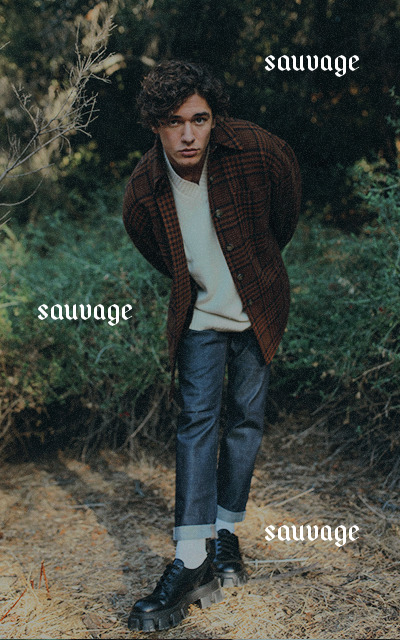

Photo

belmont cameli (white)

actor, 1998.

#belmont cameli#belmont cameli avatars#belmont cameli edits#faceclaim rp#rp faceclaim#faceclaim#rp resources#400x640

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

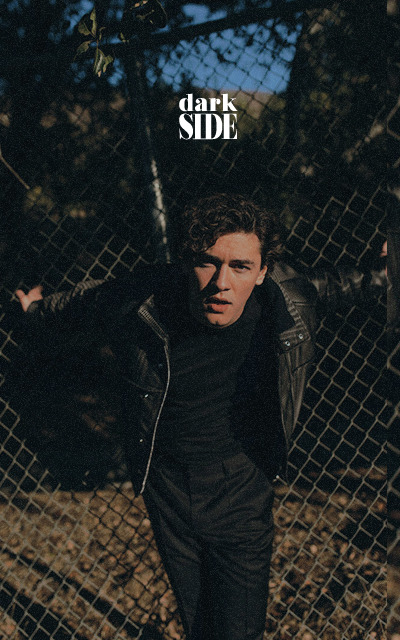

+ 9 avatars Belmont Cameli (10-18) LIEN IMGBOX

#belmont cameli#belmont cameli avatar#belmont cameli avatars#avatar#avatars#400x640#200x320#gif#gifs#photoshoot#request

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#belmont cameli#belmont cameli avatar#belmont cameli avatars#belmont cameli icons#belmont cameli 200*320#belmont cameli 200x320

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why do people critique Sonic harder than other series? Why do we need to step back and say Sonic Adventure was actually a flawed game? No one does that for other iconic games that have aged just as poorly if not worse like Zelda 1 or Metroid 1. Heck, even Mario 64 didn't get it perfect but we never have to put an asterisk on its quality but why do we have to always do that for Sonic?

Because Sonic is special.

Sonic was a franchise that shifted an entire industry when it came out. If you go back and look at platformers of the era, before 1990, everyone was desperately trying to clone the concepts of Super Mario Bros.

By late 1992, Mario clones were becoming increasingly rare, replaced instead by people chasing after Sonic the Hedgehog’s success. Sonic was a tiny revolution in terms of video game characterization. He had personality to spare, whereas most game characters of that time were blank slate player avatars. Sonic was expressive and reactionary when guys like Mario, or Mega Man, or Simon Belmont, or Link all had one single facial mood that carried them through the whole game.

That was paired with rollercoaster, pinball gameplay unlike anything else on the market at the time. It was new, and exciting, and most importantly, it was good, and Sega reaped the benefits of this. Sonic the Hedgehog became a household name. He was more popular than Mickey Mouse, one of the strongest brand identities on earth.

Sonic did not stay good. The environment Sonic was created in – a sort of east vs. west boiler – broke down across multiple levels. Key personnel were scared away by aggressive upper management. The developers that managed to stick around became burnt out over Sega riding them to maximize the Sonic cash cow. The whole thing fell apart in to a million pieces, and each piece went on to become its own microcosmic shard of the Sonic identity.

This puts the Sonic franchise in the unique position where there’s a lot to unpack on the road of “how Sonic was good and what made him become bad.” There are so many angles to view things from, so many ways to tackle the subject, because Sega’s let Sonic become so many different things. That identity crisis has lead to everybody arguing about the “true” Sonic the Hedgehog.

All of this is bolstered by the fact that a lot of “bad” Sonic games aren’t all the way bad. Even in games like Sonic 06, or Sonic Boom: Rise of Lyric, or Shadow the Hedgehog, somebody was trying to make something cool. They are never actually just bald-faced cash grabs, they’re full of legitimately good ideas that never get the time or money to come all the way to fruition. That, in itself, encourages debates over mechanics and storytelling as everyone tries to parse why the heck they like this stuff in the first place.

Sonic the Hedgehog is a mirror that must be turned back upon yourself, because there’s no way you can play more than a few of these games before you have to ask why you’re putting yourself through this. And I’d argue nobody ever comes up with a good answer, either! I don’t feel like I have. Yet here I am, been here since 1991, and I’ve yet to leave this franchise behind.

And that’s what people want to get to the bottom of.

With Super Mario 64, you say “Here’s why this game is great, here’s how it changed the industry” and you’re done. With Sonic the Hedgehog, it’s orders of magnitude longer or more complex than that, and often hard to accurately define, because it’s almost more of a feeling than a documented fact.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

OK so here’s what I figured out about Castlevania

So there’s a couple of theories of games and narrative out there, and one of the theories I particularly like is that games produce spatial narratives. Games make stories by (and stories about) exploring space. While there are good counterexamples and counterarguments and stuff, Castlevania games are a pretty straightforward example of how spatial narrative can work, and the Castlevania animated series adaptation does an excellent job of translating that.

(Funnily enough the only other good video game adaptation - literally the only one I’m aware of - is the Japanese Ace Attorney movie, and AA is a good example of a game that doesn’t entirely rely on spatial narrative - but that just goes to show how hard it is to make spatial narrative into conventional narrative so ANYWAY)

With the disclaimer that I have watched Let’s Plays and speedruns and reviews of Castlevania games but haven’t played one yet, as far as I understand it, Castlevania games are about exploring a castle, and eventually - uh - whipping Dracula? And as you play, your avatar collects new moves or new items that allow you to access new parts of the castle, and you may also speak with various characters to learn more lore and backstory.

So, how is this a spatial narrative? Well, we can loosely define narrative as a series of cause-and-effect events strung together to make a story. In a straightforward, conventional narrative, a character takes an action, and that action has an effect (bad priest man burns Dracula’s wife; Dracula becomes pissed and kills everyone). Causes and effects loop onward to create stories (tadah!). Video-game spatial narratives use cause and effect, but they use it a little differently, because the player also takes actions that create effects in the game’s world. You press a button and Trevor whips something until it dies. Cause: button press/whip. Effect: dead cyclops. Nice.

The great thing about this kind of spatial narrative is that player input and perception become really important, and that’s a great way to get you invested in your avatar character. You might feel very strongly for your lil pixel Trevor, because you control his actions and you decide where he goes. There are narrative elements that never change - you are always in Drac’s castle - but there are narrative elements that are entirely your responsibility, such as the order of rooms you explore and the actions you take to get there.

Think about how you recount playing a video game to other people: “Okay so I unlocked the door and then I almost died because I didn’t see the spiked pit, but I jumped at the last second! I AM A DODGE GOD!” That’s spatial narrative: you explore space, react to it, and that’s your story.

SO THE COOL THING THAT I NOTICED ABOUT THE CASTLEVANIA ANIME is that they figured out how to translate spatial narrative into a traditional linear narrative. Normally this is pretty hard to do. You might have enjoyed your 80-odd hours of exploring 15th-century Venice, but that wouldn’t work in an Assassin’s Creed movie. There’s no player involvement, meaning such spatial exploration would be kind of boring.

And yet....we do watch people play video games online for hours and hours at a time, very often with commentary.

Basically what I’m saying is that in the Castlevania animated series, Trevor Belmont is his own Let’s Player.

Trevor is opinionated, sarcastic, and he can’t shut his mouth. He talks to himself almost constantly, particularly throughout Episode 2 where he spends a lot of time alone. When he doesn’t talk, he’s always reacting to new information around him. He infiltrates Gresit at the beginning of Episode 2, and spends the first half of his infiltration bitching about the smell of sewers and how hungry he is. Then he has to be quiet and stealthy, so we see him smirk at a sleeping guard as he sneaks past, and we see him shiver and pull his cloak when he enters the city, and we see him spit at a pile of corpses below a bridge. These details tell us things about Trevor, but also about the state of the area he is exploring and the lore behind it. It’s cold, it’s dirty, it’s poorly guarded, and death is common in this world.

If Trevor doesn’t draw attention to the details of his surroundings, the camera will. The colour palette of most scenes is either starkly cold (like the cyclops fight or Dracula’s mirror) or very warm (all the torch-wielding mobs). I think this is why the gore is also so vivid; it’s another jarring sensory experience, a way of making violence immediate and physical without putting a controller in someone’s hand.

You see, if your audience can’t experience the spatial narrative directly, because they can’t make decisions about what gets explored and how, the next best thing is to experience spatial narrative indirectly. Trevor acts very much like a Let’s Player, because he comments on details a “player” of his situation might observe through gameplay. He voices his thought processes aloud, and he’s pretty funny about it. My favourite example of this Let’s-Playin’ is the lead-up to the fight with the cyclops, so I’ll show you what I mean.

Trevor finds a secret passage by discovering an optical illusion hiding a tunnel. He smirks and crawls in. He sniffs a torch and smells fresh oil, which he notes aloud; then he knocks on a metal pipe, and says that it’s warm. You can almost imagine those as little dialogue boxes popping up when a player interacts with those objects, hinting at methods of solving a puzzle. This feels pretty game-y, for lack of a better word: Trevor’s navigating and puzzling just like a player would.

He climbs down a set of stairs, hears a noise, and calls, “I can hear you! I’m armed and a lot less happy than you are, so stay out of my way -”

Then he falls through the floor, lands, and comments, “Hah! Reflexes like a cat!” before falling through the floor again.

In both of these cases, Trevor’s comments are quite self-reflexive: they are all first-person statements. When he hears a noise, it’s not “what was that?” it’s “I can hear you.” “[I have] reflexes like a cat”.

I found this really neat because first-person speech is a hallmark of players who are engaged with an avatar. when you’re playing and your avatar gets zapped by the cyclops, you say “I died”, not “he” died. First person speech is particularly common when you, as a player, are most deeply, immediately engaged with gameplay, as when you’re instinctively reacting to a noise or a fall.

In short, the Let’s Play continues.

Trevor then finds a room full of stone statues, and comments, “Either someone left a statue of a speaker here, or...” (Feels like another text box prompt to me - one that leads into a boss battle.)

Cyclops appears, fight ensues. Trevor comments, “A cyclops. Right out of the family bestiary.” Then he uses the columns, a shortsword, and some slick whip tricks to murder the cyclops.

So, obviously a good staple for spatial narrative is combat, and I think it’s super telling that Trevor’s fight involves using the environment to his advantage rather than just whip whip whip whip. That’s another way of making the viewer care about the space Trevor is in.

Later on, Trevor comments on the electric lights in the cyclops’ cave, pointing out that only Dracula possesses the technology for such lights. Viewers remember those lights because the camera does a good job of focusing on them, but also because we are still thinking of this narrative spatially. This show rewards spatial thinking. When Trevor is escaping from the mob in Episode 3, his clever tricks on how to navigate the town and eliminate multiple enemies are all part of the fun; it’s a circus of combat Assassin’s Creed could only dream of, but it only works because every concept here is so tightly woven together with spatial narrative.

Trevor’s running commentary helps build that Let’s Play feeling of watching someone else experience a video game just like a player would, but it also informs his character as a sassy grump who doesn’t know when to shut up. The Let’s-Play-commentary forces a focus on space, action, and sensory detail, and because viewers are concentrating on those things, the show is able to pull references like the electric lights into focus even though Trevor never comments on them verbally until after the fight. I can’t even guess which of these concepts were intentional, or which came first, because they all work together seamlessly.

and like. it’s good or whatever. idk that’s all I’ve got for now

#castlevania#castlevania series#currie academia#maybe I'll essay this out properly one day#oh yeah spoilers for the series#sorry! :D

100 notes

·

View notes

Note

I guess the amount I remember from NFCV was smaller than I originally thought. Essentially, Gabriel tries to be a thorn in His side (as he states in the reunion scene to Marie), but God still sees him as His chosen, and still gives him special privileges, such as wielding the VK and using Holy Magic. It's never stated in canon whether or not Gabriel could make holy water or even really bless things, but it's assumed by the fanon that he could.

It's actually funny. Gabriel has toxic blood, since it's also connected to the Castle and part of his dark magic, and probably also connected to his holy magic, but it states that in MoF, the vampires are people who purposely came to Gabriel to make a blood bond with him. However, it never actually states how Gabriel could do this, since his blood literally is too strong and toxic for even demons to withstand.

Imagine a lore gap about one of the main enemies in a game, and still having more consistent lore about their making than NFCV has about the Devi Forging.

The way you phrased it is hilarious 😂

Mathias: I hate You! I want to oppose You in any way I can!

God: Alright, you will become the avatar of Chaos and the closest thing to Satan on Earth, and I'll lend my power to your ex's descendants to kill you over and over.

Gabriel: I hate You! I want to oppose You in any way I can!

God: awwww but you're my specialest boy 🥺 i will never abandon you <3 here, have some holy power, as a treat <3

Anyway, this makes more sense to me because Gabriel really used to be a pious man who won God's favor. So he has cursed powers because of his nature as a vampire, but God hasn't abandoned him. Compare this to the zombie form of a cruel bishop who got told "your work makes God puke" being able to use holy powers.

And now that I think about it, Trevor doesn't use any sort of holy power either. He doesn't have the Grand Cross, he doesn't use holy water himself, and he explains that the reasons vampire hate crosses is that it fucks with their vision, not because it's God's symbol.

Trevor Belmont has no connection to God. The zombie bishop who killed Lisa does. The layers of fuckery of this show are endless.

But yeah, LoS did the "cursed creature can use holy powers" concept infinitely better from what you've told me.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

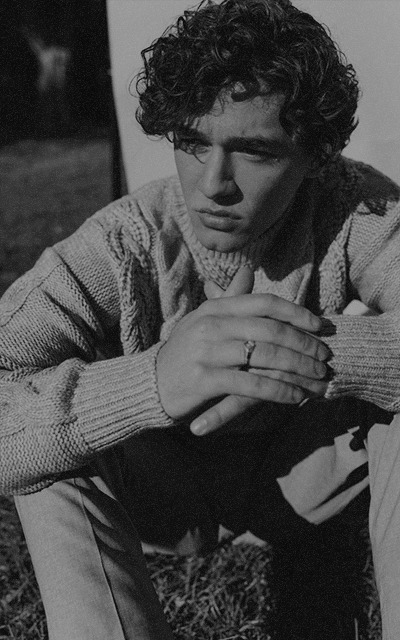

+ 9 avatars Belmont Cameli (1-9) LIEN IMGBOX

#belmont cameli#belmont cameli avatar#belmont cameli avatars#avatar#avatars#400x640#200x320#gif#gifs#photoshoot#request

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#belmont cameli#belmont cameli avatar#belmont cameli avatars#belmont cameli icons#belmont cameli 200*320#belmont cameli 200x320

7 notes

·

View notes