#born 29th july 1906

Text

Happy Birthday To Gorgeous American Actress

Thelma Todd (Born 29th July 1906)

#thelma todd#birthday girl#born 29th july 1906#gorgeous american actress#comedienne#119 acting credits to her name#years active 1926-35 & 1936#the two acting credits in 1936 were recieved posthumously

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

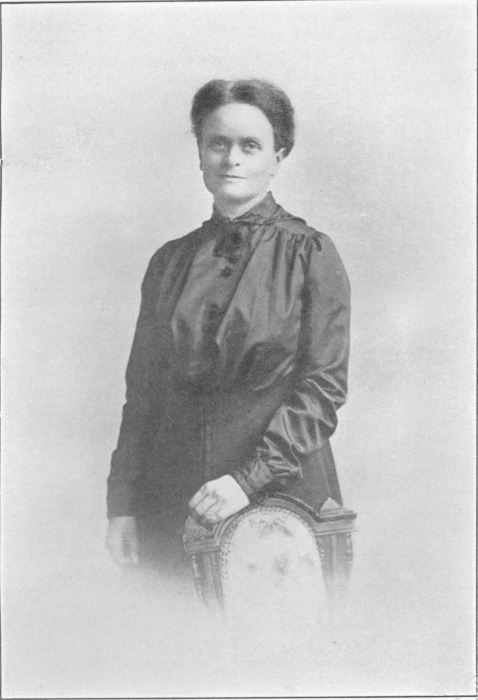

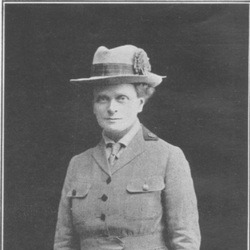

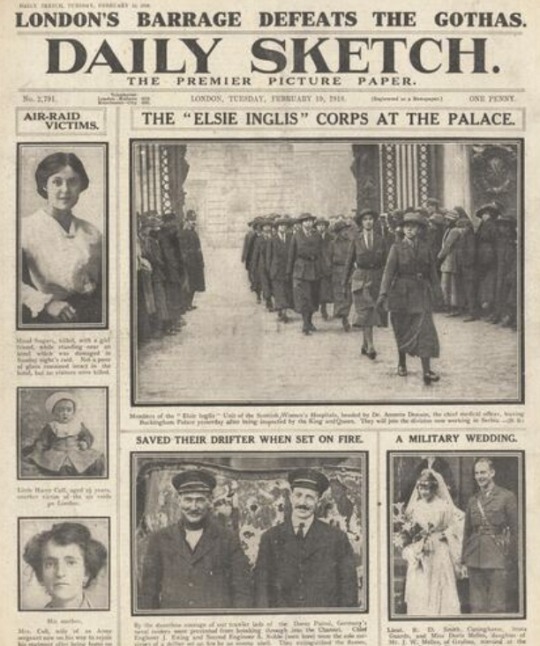

On 26th November 1917 Elsie Inglis, the Scottish nursing pioneer and suffragette, died.

There are very few people who were neither born or died in Scotland that are as highly regarded and respected as Scots, than Elsie Inglis, the only other that springs to mind is Eric Liddell.

Elsie parents were Scots Harriet Lowes Thompson and John Inglis, who worked for the East India Company, when her father retired from his job in 1878 the Inglis family returned to Scotland and settled in Edinburgh.

Having studied medicine at the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women Inglis subsequently established her own medical college. She qualified as a doctor and secured a teaching appointment at the New Hospital for Women. A keen suffragette Inglis was later to found her own maternity hospital entirely staffed by women.

In 1906 Inglis played a notable role in the establishment of the Scottish Women’s Suffrage Federation. The outbreak of war in Europe in August 1914 brought about a temporary ceasefire where political - including suffragette - issues were concerned, and Inglis promptly suggested the creation of women’s medical units on the Western Front.

The British government reacted to Inglis’s idea was frowned upon, she was told “‘my good lady, go home and sit still’. . Nevertheless a similar offer made directly to the French government was warmly received and Inglis travelled to France within three months of the outbreak of war, with the Abbaye de Royaumont hospital, containing some 200 beds, in place by December 1914. This was later followed by a second hospital at Villers Cotterets in 1917.

Inglis was active in arranging for the despatch of women’s units to other fighting areas aside from the Western Front, the first Scottish Women’s Hospital field unit was formed in December 1914 in a town called Kragujevac in Serbia.others followed at Salonika, Romania, Malta and Corsica in 1915 and to Russia the following year.

Inglis herself served in Serbia from 1915 until the Serbian government and army withdrew to Corfu ,she had been held prisoner for a period until U.S. diplomatic pressure brought about her release. Thereafter based in Russia she was taken ill, the government demanded she come home but Elsie refused until the Serbian soldiers were guaranteed safe passage. The boat brought them back to Newcastle and Elsie, who was crippled with illness, could hardly walk as she greeted Serbian soldiers on deck. She was so frail she had to be carried off to a nearby hotel where she died on 26th November 1917.

Elsie’s body was taken “home” to Edinburgh where it was interned in Dean Cemetery, beforehand it lay in state in St Giles’ Cathedral. Her funeral there on 29th November was attended by both British and Serbian royalty.

The SWH continued its work for the duration of the war, sending out more units and raising money for the work. Remaining funds were used to establish the Elsie Inglis Memorial Maternity Hospital in Edinburgh in July 1925, it closed in 1988.

There is a Memorial Drinking Fountain “Crkvenac” in Mladenovac, Serbia commemorating her work for the country. A plaque commemorates her at 8 Walker Street, Edinburgh. A portrait of her is included in the mural of heroic women by Walter P. Starmer at St Jude’s Church, Hampstead Garden, London. In 1922 a large tablet to her memory (sculpted by Pilkington Jackson) was erected in the north aisle of St Giles on Edinburgh’s Royal Mile.

A movie is set to be made of her biography, penned by her sister, Eva called The Woman With the Torch, no date yet about a release, work is ongoing as far as I can see,

Edinburgh is set to have a statue erected to Elsie, it will be the first woman to be commemorated with a statue on the Royal Mile at the site of her hospice on the High Street, which is between the Bridges and The Netherbow. Unfortunately controversy has meant it has been put on hold after a bitter row about the choice of sculptor.

Anger erupted after the trustees suspended their open call for designs and instead commissioned Stoddart, the King’s sculptor in ordinary in Scotland.

In late September, they tweeted: “The call to artists has been suspended indefinitely owing to considerations that have been brought to the attention of the trustees in recent weeks. This information has therefore rendered the brief as published suboptimal to ensure the successful outcome of the project at design scheduling and budgetary levels.”

The furore has brought fresh attention to the absence of female statuary in Edinburgh, which has dozens of monuments to male soldiers, kings, intellectuals and physicians. Those include one of Stoddart’s best-known works, a large bronze of the philosopher David Hume outside the high court near St Giles’.

Part of the problem is that some say the statue should be made by a woman, and I agree, why should a woman not get to make a a statue about a woman who did a lot for their rights. Edinburgh should be making a stand on this.

#Scotland#scottish#history#medical history#sufferagette#womens suffrage#strong woman#doctor#Edinburgh

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cracks that cripple the family | Timeline

okay, i think I've covered all basis of the timeline. Somethings might have been missed, some things i’ve tried to keep accurate and some i’ve made up bc canon’s not giving us enough.

1901

June 19th

Agustin is born.

1906

Agustín meets Julieta for the first time to be healed as a child

1926

Agustin and Julieta Wed

Pepa and Felix Wed

1928

December

Isabela is conceived

Dolores is convinced

1929

August 7th

Isabela is born

August 31st

Dolores is Born

1931

February

Luisa is conceived

November 14th

Luisa is Born

1934

March 1st

Camilo is conceived

June 19th

Agustin’s 33rd Birthday | Mirabel’s conception

June 29th

Agustin is forced to leave | Leaves Encanto

Dolores follows Agustin | Leaves Encanto.

Agustín is attacked by jaguar | dragged to new town

Dolores saves Agustin | Drags her tio to a closer town

June 30th

Agustín is taken in by new town

Dolores is taken in by new town

Mid-July

Scars have healed | Agustin starts work

Dolores attends school | first meets Diego Moreno

Agustin befriends Jovan Moreno

August 7th

Dolores’s 7th Birthday

September 15th

Agustín and Dolores celebrate Jovan and Beatriz late pregnancy announcement

December 28th

Camilo is born

1935

February

Clara Moreno is born

March 6th

Mirabel is born

1936

August 17th

Agustín's annulment is filed and processed

Isaac is conceived in-between Agustín and Imelda

October 20th

Agustín and Imelda Wed

1937

May 17

Isaac Rojas is born

1940

January 10th

Miguel Rojas is born

1943

August 31st

Dolores’s quinceañera

September

Dolores accepts Diego’s date.

Diego stars work at Jovan’s workshop

1944

January

Dolores and Diego have their first time.

Dolores take a job

1945

April 2nd

Agustín and Imelda visit Antonia in the city.

Train Details at the station

Agustin is injured

Imelda is killed immediately.

April 20th

Imelda’s funeral

May 1st

Agustin is released from hospital

May 21st

Antonio is born

December 31st

Diego saves Dolores

1946

October 24th

Dolores and Diego are engaged

1947

Diego and Dolores increase work for wedding funds

1948

1949

Dolores and Diego Wed

September

Dolore and Diego’s first child is conceived

1950

May 21st

Antonio’s gift ceremony

June 3rd

Mirabel Discover's Agustin’s lost glasses

June 4th

Mirabel finds out who they belong to.

Mirabel meets her paternal Abuela and Abuelo

Agustin and Dolores are assumed deceased.

Vera Rojas confronts Alma about her son’s death

Collapse of Casita

Bruno reveals himself back.

Reveal of Dolores and Agustin’s survival

June 5th

Felix, Mirabel and Isabela leave for the new town

The trio see Dolores and Agustin at a cafe

Felix accidently knocks Agustin into the ground

#cracks that cripple the family au#diego moreno#dolores madrigal#agustin madrigal#agustín madrigal#encanto au#encanto#alma madrigal#pepa madrigal#felix madrigal#camilo madrigal#antonio madrigal#mirabel madrigal#bruno madrigal#julieta madrigal#luisa madrigal#isabela madrigal

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐨𝐜 𝐛𝐢𝐫𝐭𝐡𝐝𝐚𝐲 𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐭.

because i am quite simply done with getting all my ocs’ birthdays mixed up, so here is a comprehensive list of all my existing ocs’ birthdays (or at least the birthdays of those in universes where time is measured the same way as ours, or who aren’t beings born centuries ago), so you know and i don’t forget!

bowie forrester (911): august 12th, 1991 (zodiac sign: leo).

dot watanabe (the a-team 2010): july 7th, 1978 (zodiac sign: cancer).

javi martinez (the a-team): october 30th, 1945 (zodiac sign: scorpio).

nicky bauer (brooklyn nine-nine): march 2nd, 1981 (zodiac sign: pisces).

felix wilkinson (back to the future): january 30th, 1969 (zodiac sign: aquarius).

adam kelleher (the batman): june 27th, 1994 (zodiac sign: cancer).

cher johnston (bill & ted): september 8th, 1972 (zodiac sign: virgo).

wyatt friedman (one chicago): april 3rd, 1979 (zodiac sign: aries).

kai hallows (the chronicles of narnia): perceived zodiac sign: gemini.

hemera (the chronicles of narnia): perceived zodiac sign: pisces.

alaric ryker (the chronicles of narnia): perceived zodiac sign: aquarius.

eli logan (criminal minds): september 30th, 1977 (zodiac sign: scorpio).

eddie baker (criminal minds): april 30th, 1970 (zodiac sign: taurus).

briar malcolm (criminal minds): january 13th, 1972 (zodiac sign: capricorn).

donnie carver (dc comics): february 9th, 1989 (zodiac sign: aquarius).

ivana morozova (dc comics): august 20th, 1998 (zodiac sign: leo).

paisley harlow (dc comics): may 11th, 2000 (zodiac sign: gemini).

elena isley (dc extended universe): december 1st, 1994 (zodiac sign: sagittarius).

greta dwarf (disney’s descendants): april 30th, 1999 (zodiac sign: taurus).

sebastian white (disney’s descendants): november 25th, 1999 (zodiac sign: sagittarius).

flo sánchez (fast & furious): may 29th, 1975 (zodiac sign: aries).

aj vargas (fast & furious): july 10th, 1976 (zodiac sign: cancer).

evie young (frasier): october 3rd, 1958 (zodiac sign: libra).

ria santos (friends): december 31st, 1969 (zodiac sign: capricorn).

samantha ross (ghostbusters): july 23rd, 1959 (zodiac sign: leo).

audrey beiste (glee): september 28th, 1994 (zodiac sign: libra).

leo cooper (glee): march 31st, 1994 (zodiac sign: aries).

parker holloway (glee): november 4th, 1994 (zodiac sign: scorpio).

bruno keeley (glee): may 10th, 1994 (zodiac sign: taurus).

ivy kekoa (glee): february 9th, 1994 (zodiac sign: aquarius).

bailey taylor (glee): may 31st, 1994 (zodiac sign: gemini).

mara yang (glee): september 17th, 1994 (zodiac sign: virgo).

luci evans (good omens): october 13th, 1983 (zodiac sign: libra).

zazzadon (good omens): perceived zodiac sign: leo.

ilya dramir (grishaverse): perceived zodiac sign: taurus.

catta rostova (grishaverse): perceived zodiac sign: virgo.

anastasia upland (the hunger games): perceived zodiac sign: capricorn.

lucy scrubb (indiana jones): march 12th, 1906 (zodiac sign: pisces).

willow madden (john wick): january 4th, 1974 (zodiac sign: capricorn).

marnie hoffman (jumanji: welcome to the jungle): april 2nd, 2000 (zodiac sign: aries).

enola holmes (the league of extraordinary gentlemen): september 29th, 1879 (zodiac sign: libra).

theo ester (mcu): july 12th, 1978 (zodiac sign: cancer).

elin eriksdottir (mcu): perceived zodiac sign: aries.

daniel garcía (mcu): september 20th, 1987 (zodiac sign: virgo).

helios (mcu): perceived zodiac sign: pisces.

dev kahtri (mcu): may 5th, 1980 (zodiac sign: taurus).

annie liu (mcu): june 2nd, 1990 (zodiac sign: gemini).

mack mackenzie (m*a*s*h): august 7th, 1916 (zodiac sign: leo).

laurens gates (national treasure): may 23rd, 1971 (zodiac sign: gemini).

adachi star (one piece): perceived zodiac sign: leo.

hayashi lark (one piece): perceived zodiac sign: libra.

morvant bellatrix (one piece): perceived zodiac sign: virgo.

yami corvo (one piece): percieved zodiac sign: leo.

august cullen (outer banks): may 30th, 2004 (zodiac sign: gemini).

drew tanaka (outer banks): march 18th, 2004 (zodiac sign: pisces).

bird mcintosh (the outsiders): april 20th, 1949 (zodiac sign: taurus).

lake mcintosh (the outsiders): april 20th, 1949 (zodiac sign: taurus).

lydia chen (percy jackson): july 10th, 2011 (zodiac sign: cancer).

arabella larson (percy jackson): january 7th, 2007 (zodiac sign: capricorn).

noelle perez (percy jackson): november 12th, 2007 (zodiac sign: scorpio).

drew phillipa (riverdale): october 10th, 2001 (zodiac sign: libra).

molly perbesi (scream): november 1st, 1980 (zodiac sign: scorpio).

layla dupreti (star trek): perceived zodiac sign: aquarius.

genesis welton (star trek): perceived zodiac sign: capricorn.

zara dolomar (star wars): perceived zodiac sign: sagittarius.

cassiopeia jinn (star wars): perceived zodiac sign: capricorn.

lianna singh (star wars): perceived zodiac sign: cancer.

via winchester (supernatural): april 13th, 1990 (zodiac sign: aries).

will welton (ted lasso): june 10th, 1976 (zodiac sign: gemini).

tabitha “tabby” aquino (teen wolf): july 3rd, 1994 (zodiac sign: cancer).

marina azevedo (teen wolf): november 29th, 1994 (zodiac sign: sagittarius).

lucinda “hale” (teen wolf): perceived zodiac sign: leo.

april hannigan (teen wolf): october 27th, 1994 (zodiac sign: scorpio).

alex wan-stilinski (teen wolf): may 5th, 1988 (zodiac sign: taurus).

anubis “andy” zhao (teen wolf): june 11th, 1994 (zodiac sign: gemini).

morrigan ravenroth (tolkeinverse): percieved zodiac sign: taurus.

reyna "sweetheart" castillo (top gun: maverick): october 9th, 1993 (zodiac sign: libra).

clarke taleb (triple frontier): december 18th, 1986 (zodiac sign: sagittarius).

avi chawla (twilight): july 10th, 1799 (zodiac sign: cancer).

catie greer (twlight): january 31st, 1993 (zodiac sign: aquarius).

isaac holliday (twilight): may 22nd, 1967 (zodiac sign: gemini).

rio varma (venom): march 19th, 1987 (zodiac sign: pisces).

esther st. claire (wednesday): august 24th, 2006 (zodiac sign: virgo).

rosaline craven (wizarding world): september 11th, 1990 (zodiac sign: virgo).

cat holmes (wizarding world): december 31st, 1960 (zodiac sign: capricorn).

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎂 Happy Heavenly Birthday to the beautiful and funny actress Thelma Todd who was born on this date; July 29th, 1906 in Lawrence, Massachusetts💐.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881 – 1938) was the founder and the first President of the Republic of Turkey. Mustafa Kemal was born in 1881 in Salonika (Thessaloniki, today in Greece, then under the Ottoman rule). His father’s name was Ali Riza Efendi. His father was customs official.

His mother’s name was Zübeyde Hanim. For his primary education, he went to the school of Semsi Efendi in Salonika. But Mustafa lost his father at an early age, he had to leave school. Mustafa and his mother went to live with his uncle in the countryside. His mother brought him up. Life continued like this for a time. Mustafa worked on the farm but his mother began to worry about his lack of schooling. It was finally decided that he should live with his mother’s sister in Salonika.

He entered the Military Middle School in Salonika. In 1895, after finishing the Military Middle School, Mustafa Kemal entered the Military High School (Askeri Idadisi) in Manastir.

After successfully completing his studies at the Manastir Military School, Mustafa Kemal went to Istanbul and on the 13th of March 1899 he entered the infantry class of the Military Academy (Harbiye Harp Okulu). After finishing the Military Academy, Mustafa Kemal went on to the General Staff College in 1902. He was graduated from the Academy with the rank of captain on the 11th of January, 1905.

In 1906, he was sent to Damascus (Sam). Mustafa Kemal and his friends founded a society which they called “Vatan ve Hürriyet” (Fatherland and Freedom) in Damascus. On his own initiative, he went to Tripoli during the war with Italy in 1911 and took part in the defense of Derne and Tobruk. While he was still in Libya, the Balkan War broke out. He served in the Balkan War as a successful Commander (1912-1914). At the end of the Balkan War, Mustafa Kemal was appointed military attaché in Sofia.

When Mustafa Kemal was in Sofia, the First World War broke out. He was made Commander of the Anafartalar Group on 8th of August, 1915. In the First World War he was in command of the Turkish forces at Anafartalar at a critical moment. This was when the Allied landings in the Dardanelles (Canakkale Bogazi) took place and he personally saved the situation in Gallipoli. During the battle, Mustafa Kemal was hit by shrapnel above the heart, but a watch in his breast pocket saved his life. Mustafa Kemal explained his state of mind as he accepted this great responsibility: “Indeed, it was not easy to shoulder such responsibility, but as I had decided not to live to see my country’s destruction, I accepted it proudly”. He then served in the Caucasus and in Syria and just before the armistice in 1918 he was placed in command of the Lightning Army group in Syria. After the armistice (peace agreement), he returned to Istanbul.

After the Armistice of Montreux, the countries that had signed the agreement did not consider it necessary to abide by its terms. Under various pretexts the navies and the armies of the Entente (France, Britain and Italy) were in Istanbul, while the province of Adana had been occupied by the French, and Urfa and Maras by the British. There were Italian soldiers in Antalya and Konya, and British soldiers in Merzifon and Samsun. There were foreign officers, officials and agents almost everywhere in the country.

On the 15th of May 1919 the Greek Army landed in Izmir with the agreement of the Entente. Under difficult conditions, Mustafa Kemal decided to go to Anatolia. On 16th of May 1919, he left Istanbul in a small boat called the “Bandirma”. Mustafa Kemal was warned that his enemies had planned to sink his ship on the way out, but he was not afraid and on Monday19th May 1919, he arrived in Samsun and set foot on Anatolian soil. That date marks the beginning of the Turkish War of Independence. It is also the date that Mustafa Kemal later chose as his own birthday. A wave of national resistance arose in Anatolia. A movement had already begun in Erzurum in the east and Mustafa Kemal quickly placed himself at the head of the whole organization. The congresses in Erzurum and Sivas in the Summer of 1919 declared the national aims by a national pact.

When the foreign armies occupied Istanbul, on 23rd of April 1920 Mustafa Kemal opened the Turkish Grand National Assembly and hence established a provisional new government, the centre of which was to be Ankara. On the same day Mustafa Kemal was elected President of the Grand National Assembly. The Greeks, profiting by the rebellion of Cerkez Ethem and acting in collaboration with him, started to advance towards Bursa and Eskisehir. On the 10th of January 1921, the enemy forces were heavily defeated by the Commander of the Western Front, colonel Ismet and his troops. On the 10th of July 1921, the Greeks launched a frontal attack with five divisions on Sakarya. After the great battle of Sakarya, which continued without interruption from the 23rd of August to the 13th of September, the Greek Army was defeated and had to retreat. After the battle, the Grand National Assembly gave Mustafa Kemal the titles of Ghazi and Marshal. Mustafa Kemal decided to drive the enemies out of his country and he gave the order that the attack should be launched on the morning of the 26th of August 1922. The bulk of the enemy forces were surrounded and killed or captured on the 30th of August at Dumlupinar.

The enemy Commander-in-Chief, General Trikupis, was captured. Or the 9th of September 1922 the fleeing enemy forces were driven into the sea near Izmir. The Turkish forces, under the extraordinary military skills of Kemal Atatürk, fought a War of Independence against the occupying Allied powers and won victories on every front all over the country.

On the 24th of July 1923, with the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, the independence of the new Turkish State was recognized by all countries. Mustafa Kemal built up a new, sturdy, vigorous state. On the 29th of October 1923, he declared the new Turkish Republic. Following the declaration of the Republic he started to his radical reforms to modernize the country. Mustafa Kemal was elected the first President of the Republic of Turkey.

Atatürk made frequent tours of the country. While visiting Gemlik and Bursa, Atatürk caught a chill. He returned to Istanbul to be treated and to rest, but, unfortunately Atatürk was seriously ill. He spent his last days of life on the presidential yacht of Savarona. At 9.05 AM on the 10th of November 1938, Atatürk died, but he attained immortality in the eyes of his people. Since the moment of his death, his beloved name and memory have been engraved on the hearts of his people. As a commander he had been the victorious of many battles, as a leader he had influenced the masses, as a statesman he had led a successful administration, and as a revolutionary he had striven to alter the social, cultural, economic, political and legal structure of society at its roots. He was one of the most eminent personalities in the history of the world, history will count him among the most glorious sons of the Turkish nation and one of the greatest leaders of mankind.

1 note

·

View note

Text

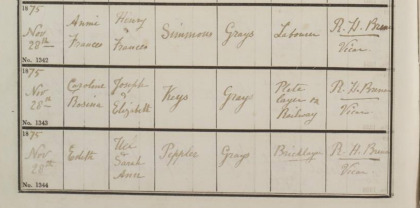

This is the sixth in my series of blogs, writing the biographies and life stories of my eight Great-Grandparents, next up is Caroline Rosina Keyes (Granny Chiddicks).

Caroline Rosina Keyes was born 9th September 1875, she was the first child of Joseph Keyes and Elizabeth Keyes nee Bishop. She was born in Grays in Essex and was baptised on 28th November 1875 at St. Peter and St Paul’s Church in Grays, coincidentally the same Church that I was Baptised in myself! At the time her Father, Joseph Keyes was a Plate Layer on the Railways.

There a couple of links here that give an insight into the role of a Plate Layer and the type of work that this involved.

Platelayer Info

Platelayers Organisation

At the time of the 1881 Census, the family are living at 18, Chapel Row, Grays, Essex and Five year old Caroline is living with both her parents and two younger siblings, Clara Elizabeth Keyes and William Henry Keyes.

1881 Census

By the time of the 1891 Census, Caroline is listed as a scholar and still living at home with her parents at 26, Prospect Row Grays. She is also with siblings, William Henry Keyes, Albert George Keyes, Rose Amelia Keyes and Alice Maud Keyes.

1891 Census

Between the 1891 Census and the 1901 Census, Caroline Rosina meets her husband to be, William Chiddicks and they are married on 3rd April 1897 at The Parish Church, Plaistow.

William Chiddicks was the first born child to James Chiddicks and Elizabeth Chiddicks nee Lake. At the time of the Marriage Caroline was listed as a Spinster with no rank or profession listed and they were both living at 19, Winkfield Road, Plaistow.

(19, Winkfield Road, Plaistow)

There are no direct family connections that I have been able to find, that would explain why William and Caroline married in Plaistow, but there are two possible explanations. they could have moved for William to find work of course, but I suspect that the real reason is because their first born child, Louisa Alice Chiddicks was born just four months after their Marriage, on 20th August 1897. sadly she dies just a few weeks later on 12th September 1897. By the time that Louisa’s death was registered, Caroline and William were living back at South Ockendon.

Four years later, at the 1901 census the family were living at Station Road, South Ockendon and had two further surviving children, Herbert Ernest Chiddicks born 28th August 1898 and William Leonard Chiddicks (Known as Len), born 14th January 1900.

1901 Census

A further Son, Frederick James Chiddicks, was born 4th August 1901 in South Ockendon and by the time their next Son was born, Percy Edward Chiddicks on 13th July 1903, the family had moved home to 44, Benson Road, Grays.

Two more children were born in 44, Benson Road, Florence Lilian Chiddicks born 24th January 1906 and Horace Frank Chiddicks (My Grandad) born 21st August 1907.

(44, Benson Road, Grays)

The family then moved to 12, Brook Road, Grays and had two more girls, Hilda May Chiddicks born 10th March 1909 and Gladys Maud Chiddicks born 29th April 1913. Around this time the family were counted in the 1911 Census still living at 12, Brook Road, Grays, with all seven children still living at home.

(Brook Road, Grays)

1911 Census

Caroline is next found on several Electoral Registers again living at 12 Brook Road, with her Husband William.

1931 Electoral Register

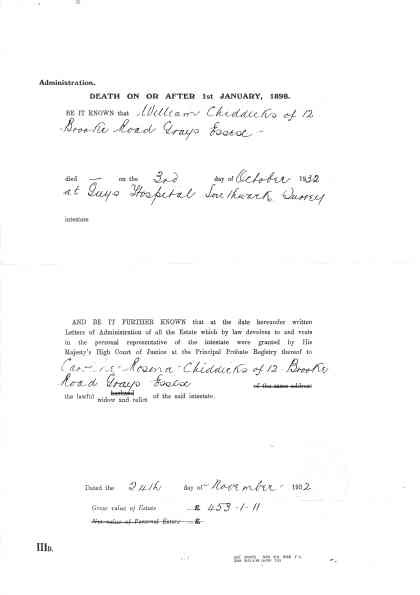

The next record that we find for Caroline Rosina follows the sad Death of her Husband William Chiddicks on 3rd October 1932. William left a Will and left his widow Caroline Rosina Chiddicks the sum of £453 1s. 11d. (which is worth appx £30,000 in today’s money).

My Aunt remembers as a child visiting Granny Chiddicks house, which was a large white house located at Sockets Heath in Grays and this fact is supported by her entry in the Electoral Register for 1936 living at “Woodmead”, Sockets Heath, Grays, Essex.

(CHECK MY RECORDS FOR A COPY OF ELECTORAL REGISTER MIGHT BE REALLY EALRY STUFF FROM GRAYS LIBRARAY)

(6, Fairleigh Drive, Southend-on-Sea)

By the time of the 1939 Register, Caroline Rosina is living with her Son-in-Law Edwin Bradford and her Daughter, Florence Bradford nee Chiddicks at 6, Fairleigh Drive, Southend-on-Sea, Essex. By this time her husband William Chiddicks had died and she is listed as a Widow, living off Private Means, old age Pension.

1939 Register

For the remainder of her life, Granny Chiddicks remained living with her Daughter and Son-in-Law at 6, Fairleigh Drive, Leigh-on-Sea, Essex. At some point towards the end of her life she was admitted to the Connaught House old people’s Hostel, where she sadly died on 19th December 1960, at the age of 85. She was cremated at Rochford Crematorium on 22nd December 1960 and her ashes placed in the Garden of Rest on 31st December 1960 in area X.10. Her Daughter, Florence Lilian Bradford applied for the Cremation to take place.

Connaught House Past and Present

(Images kindly supplied by Rochfordtown.com )

After 1948, the former Southend workhouse became Connaught House old person’s hostel, and most of the former workhouse buildings were demolished in the late 1990s.

The Life and Times of Caroline Rosina Keyes This is the sixth in my series of blogs, writing the biographies and life stories of my eight Great-Grandparents, next up is Caroline Rosina Keyes (Granny Chiddicks).

#Ancestry#ancestrydna#Archives#Blog#christmas#Essex#family#Family History#Family Tree#Genealogy#genetics#History#Image#Library#museum#Newspaper#nostalgia#photo#thurrock#Writing

0 notes

Text

In Memoriam: Billy Mitchell, Father of the United States Air Force

In Memoriam: Billy Mitchell, Father of the United States Air Force

In 1906 — two years before he witnessed a flying demonstration by Orville Wright — Billy Mitchell, an instructor at the Army Signal School, saw the future of war: in the coming years, battles would be fought and won in the air. After coming home from WWI with a reputation as a top combat airman, he campaigned for increased investment in air power at the cost of maintaining a large surface fleet.

When his pleas fell on deaf ears, he became more strident and more outspoken, believing the future of the United States to be at stake. So strong was his desire to be heard that he openly criticized his superiors, angering Army and Navy administrators and at least three presidents in the process. An abrasive and caustic man, he was court-martialed in 1925, found guilty, and suspended, essentially ending his military career…but not before organizing a demonstration that showed the potential of air superiority. Billy Mitchell died in 1936, years before he could dream of seeing his beliefs come good—but his impact on military doctrine cannot be overstated.

With this In Memoriam, we’ll be looking at the life and legacy of this complicated and controversial man.

Early Life and Career

Billy Mitchell was born on December 29th, 1879, to Wisconsin Senator John L. Mitchell and his wife Harriet. Mitchell grew up near Milwaukee, WI, and enlisted as a private at the age of 18. His father’s political influence granted young Mitchell an opportunity for a commission, and he joined the US Army Signal Corps (which develops, tests, and manages communications and information systems for the US Military) with the goal of fighting in the Spanish-American War.

Lt. Mitchell in Alaska

The war ended before he saw any action, but he stayed with the Army Signal Corps, and in 1900 was sent to the District of Alaska to oversee the establishment of a communication system to connect the many isolated outposts and gold rush camps. It was there where Mitchell, now a Lieutenant, read about the monumental glider experiments performed by Otto Lilienthal, who was the first person to document repeatable, successful flights with unpowered aircraft. These experiments had a profound impact on Mitchell, and in 1906, while an instructor at the Army Signal School in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, he gave his now-famous prediction about the future of warfare.

But it wasn’t the only of Mitchell’s predictions that came true. In 1912, upon a tour of the battlefields of the Russo-Japanese War, he concluded that war with Japan was inevitable. Later, he went so far as to predict that Japan would attack Pearl Harbor without a formal declaration of war. In this regard, Billy Mitchell was a true visionary.

In 1916, at age 37, he finally took flying private lessons at great personal expense (he was disqualified from formal military training due to age and rank). In July, 1916, he was promoted to Major and appointed Chief of the Air Services of the First Army.

WWI

Mitchell was sent to France as an observer in 1917, a task for which he was uniquely suited, thanks to his exceptional organizational and writing skills, and the fact that he spoke French. It was there where he began collaborating with senior aviation leadership from Britain and France, who taught Mitchell the basics of aerial combat strategy and major air operations. Among these was British Major General Hugh “Boom” Trenchard, himself known as “Father of the Royal Air Force,” who had been establishing the airpower playbook for years before Mitchell arrived.

At the onset of America’s entry into WWI, the Army Signal Corps Aviation Section (the “air force” then) had just over 50 aircraft, many not operational. Just a year and a half later, Billy Mitchell, now a Brigadier General, was given command of all American air units in General Pershing’s American Expeditionary Force, and orchestrated the air campaign of the Battle of St. Mihiel, coordinating nearly 1,500 Allied aircraft. What started inauspiciously ended as a major triumph—a testament to both America’s industrial prowess and to Mitchell’s exceptional command.

As Mitchell once wrote about the battle, “It was the first time in history in which an air force, cooperating with an army, was to act according to a broad strategical plan.” And it was a success. This further cemented Mitchell’s beliefs about the power of controlling the skies. “[WWI had] conclusively shown that aviation was a dominant element in the making of war, even in the relatively small way in which it was used,” he wrote.

Mitchell (left) with his gunner, leaning against a Spad aircraft

Though given his initial command because of his status, he proved to be a daring and uniquely qualified leader. For his actions, he was given the Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal.

More importantly, these successes contributed to his core belief that the Air Service had to be well-prepared at the start of the next great war, or the US could potentially lose before it ever fought.

He would spend the rest of his career working towards that preparedness…and openly challenging those who opposed.

Post-War: The Crusade Begins (1919-1921)

Mitchell knew very well that the “War to End All Wars” had accomplished something short of its moniker, and that “If a nation ambitious for universal conquest gets off to a flying start in a war of the future, it may be able to control the whole world more easily than a nation has controlled a continent in the past.”

To his horror, demobilization was the order of the day. Of the nearly 200,000 officers and men who were assigned to the Air Service at the end of the war, only 10% remained. He was appalled.

He did everything he could to prepare for the next conflict. To that end, he encouraged pilots to set world speed records to raise public consciousness. He organized long-distance air routes and simulated bombing attacks on New York. He proposed a special corps of mechanics, troop-carrying aircraft, bombers capable of transatlantic range, and—most notably���bombsights.

Mitchell in his element

But Mitchell knew that these small victories could only accomplish so much. True preparedness would require a fundamental change in thinking at the top levels of military leadership. He took every opportunity to advocate for the establishment of a separate, independent air force at the cost of spending on the surface fleet…which put him in direct conflict with US Navy leadership, notably Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt (this was the first future or sitting president Mitchell’s behavior would incense).

Understanding what Mitchell was up against requires an understanding of the Navy doctrine of the day—the Mahanian Doctrine. In 1892, Alfred Thayer Mahan, former Rear Admiral for the U.S. Navy, released his seminal work titled The Influence of Sea Power Upon the French Revolution and Empire. The book, in short, claimed that national greatness was inexorably linked with command of the sea by means of “capital ships, not too large but numerous, well-manned with crews thoroughly trained.” Mahan became world-famous, his work influencing the military elite in Great Britain, France, Japan, and here in the US.

It cannot be overstated just how pervasive Mahanian Doctrine was at the time. To those in senior leadership positions, a country’s military might was measured in battleships.

Of course, Mitchell disagreed vehemently. He maintained that expensive dreadnoughts could be easily sunk by bombs dropped from an aircraft. Mitchell faced an uphill battle. And if senior military leadership wouldn’t listen to him, he would plead his case to congress, media, public, and anyone else who would listen.

Mitchell’s beliefs can be summarized briefly:

Dreadnoughts had become obsolete, and could be destroyed easily by bombs dropped from aircraft.

There should exist an independent Air Force, equal to the Army and Navy.

A force of anti-warship airplanes could defend a coast more economically than coastal guns and naval vessels, and that the use of “floating bases” was necessary to defend the nation from naval threats.

The United States needed the ability to strike at the industrial heart of enemy powers via strategic bombing. (Please note that this is not a complete representation of his beliefs.)

The media by and large took his side, and argued that Mitchell should be allowed to conduct tests on actual warships, either captured or soon to be scuttled.

He would soon get his chance.

Project B: The Sinking of the Ostfriesland (1921)

After some pressure from the media and from congress, Secretary of War Newton Baker and Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels agreed to a demonstration, held on July 20, 1921, whereby Mitchell’s aircraft would try to sink a captured German ship called the Ostfriesland.

True to form, Mitchell oversaw every aspect of preparing, right down to the building of the one-ton bombs.

The rules of the test favored the survivability of the ship—Navy construction experts would get to examine the ship between each bombing run—but Mitchell was never one to let rules get in the way of proving his point. Directing the action from his biplane Osprey, he had his airmen bombard the Ostfriesland…and in a 20-minute period, it sank to the bottom of the sea.

Sinking of the Ostfriesland, from the US Army Air Service Photographic School

Though the results were “dubious” to some…he had broken the rules, and perhaps a well-trained damage control team could patch the hull…the captured battleship was indeed sunk by aerial bombs — a fact that was impossible to ignore.

He replicated the results by sinking the retired battleship USS Alabama in September of the same year, angering President Warren Harding (the second President to react this way to Mitchell), who didn’t want any show of weakness before the Washington Naval Conference.

A wonderful photo of the retired USS Alabama getting hit by a white phosphorous bomb

Mitchell’s campaign was tireless. To fight the status quo, he had to resort to stronger and stronger rhetoric, often agitating—even embarrassing— his superiors. “All aviation policies, schemes and systems are dictated by the non-flying officers of the Army and Navy, who know practically nothing about it,” he said publicly. He ruffled a few feathers, to say the least.

As a punishment, sr. staff sent him to Hawaiii, but he only returned with a scathing review of the lack of preparedness. Then, they sent him to Asia…but it only served to deepen his conviction that war with Japan was inevitable. These two anecdotes are very revealing of the man’s character and ambition: he knew he was being exiled, but still did his best to warn sr. leadership of vulnerabilities. This was, for all intents and purposes, classic Billy Mitchell.

When he returned in 1924, he offered yet another eerily accurate prediction: “His theory was that the military strength of the United State was so great, in Japanese eyes, that Japan could win a war only by using the most advanced methods possible. Those methods would include the extensive use of aircraft,” wrote Gen. James Doolittle in his book I Could Never Be So Lucky Again: An Autobiography.

One very important thing remains to be said about the sinking of the Ostfriesland. Just days after, Congress funded the very first aircraft carrier.

The Court-Martial (1925)

He kept crusading, and little by little, funding for aviation was increased. Still, though, leadership dragged its feet. And more airmen were paying the price. The aging aircraft were becoming dangerous to fly. A Navy plane en route to Hawaii a crashed into the sea. Two days later, a Navy dirigible over Ohio crashed. Mitchell, now especially angry, stepped up the scathing rhetoric.

In September 1925, he issued a stunning statement:

“These incidents are the direct result of the incompetency, criminal negligence, and almost treasonable administration of the national defense by the Navy and War Departments.”

This proved to be the final straw.

One month later, a charge with eight specifications was proffered against Mitchell under the 96th Article of War. This came from the direct order of President Calvin Coolidge, the third president to take umbrage at Mitchell’s methods.

Mitchell standing stoically amidst the tumult of his court-martial

Mitchell welcomed the court-martial if it forced the public to take notice.

Unsurprisingly, Mitchell was found guilty of all specifications and of the charge. He was suspended from active duty for five years without pay, which was amended by President Coolidge to half pay. Instead, he resigned on February 1st, 1926, and spent the next decade campaigning for air power to anyone he could.

Billy Mitchell died on February 19th, 1936 at the age of 56.

The Measure of a Man

Billy Mitchell’s legacy is complicated. Was he caustic and overzealous in his pursuit of a unified, separate Air Force? Yes. Was his court-martial and subsequent guilty verdict deserved? Absolutely. He was openly insubordinate to his superiors—who, by the way, were great men, American heroes.

But he was absolutely right.

Without him, we may not have been prepared to fight WWII in the air. “Many of his observations were proven during WWII, and his ultimate goal of an independent air force was realized in September 1947, over 11 years after Mitchell’s death,” wrote Lt. Col. Johnny R. Jones, USAF, in the Foreword of his compilation of Mitchell’s unpublished writings. In 1946, 10 years after his deatch

He was decades ahead of other airpower theorists of his time, and without him, who knows what the state of air services would have been in WWII? The answer to that questions…and so many others…we will never get.

Billy Mitchell was a fine commander, an exceptional coordinator, and, above all, a man of great courage who knowingly sacrificed his career to challenge the status quo and to educate politicians, policy-makers, and the public on matter of aviation. He was a visionary who saw the future of airpower so clearly that his words still ring true now. We owe him a debt we can never properly repay.

Today, we honor Major General William Lendrum “Billy” Mitchell, as we honor so many others for their sacrifices in serving our great nation. Thank you, Billy, and thank you to all those who serve and have served.

Notes

In limiting the scope of this article, I’ve done a major disservice to two men who contributed a great deal to aviation in Mitchell’s time. The first is General Benjamin Foulois, Mitchell’s chief rival and an aviator who learned to fly the first military planes purchased from the Wright Brothers. The second is Major General Mason Patrick, whose steady hand brought about the establishment of the Army Air Corps in 1926—and who often had to clean up the messes left behind in the constant sparring between Mitchell and Foulois.

It would be disingenuous to claim that everyone in senior leadership positions disagreed with Billy Mitchell. Admiral William S. Sims once said “The average man suffers very severely from the pain of a new idea…it is my belief that the future will show that the fleet that has 20 airplane carriers instead of 16 battleships and 4 airplane carriers will inevitably knock the other fleet out.”

A by-product of my decision to focus on Mitchell’s great courage in sparring with his superiors is that I haven’t done justice to his exceptional training and organizational skills. There’s a wealth of information on the subject out there on the internet; my favorite was “Billy Mitchell and the Great War, Reconsidered,” by James J. Cooke, Professor Emeritus of History, University of Mississippi.

Mitchell was a gifted writer, and his output was prodigious: more than 60 articles for publication, several newspaper series, and five books, all of which aimed to provide a “public understanding of the promise and potential of air power.” – “William ‘Billy’ Mitchell: Air Power Visionary,” C.V. Glines, Historynet.com

In 1930, Mitchell boldly predicted that his children would live to see the US go to space. Again, he was right.

Mitchell wasn’t always right. He significantly undervalued aircraft carriers, thinking them incapable of launching enough aircraft to be significant contributors to victory. He later changed course on the matter.

During the court-martial, Maj. Gen. Douglas MacArthur voted “not guilty” on the basis that a senior officer should not be silenced for disagreeing with his superiors in rank and with accepted doctrine. MacArthur later said that the order to sit on the court-martial was one of the most distasteful he ever received.

Just one more note…I’ve never served, and as hard as I have tried to get my terminology correct and not be disrespectful, I admit that I may have made a misstep. Please feel free to correct me. – Thanks

http://ift.tt/2zH7uho

0 notes

Text

In Memoriam: Billy Mitchell, Father of the United States Air Force

In Memoriam: Billy Mitchell, Father of the United States Air Force

In 1906 — two years before he witnessed a flying demonstration by Orville Wright — Billy Mitchell, an instructor at the Army Signal School, saw the future of war: in the coming years, battles would be fought and won in the air. After coming home from WWI with a reputation as a top combat airman, he campaigned for increased investment in air power at the cost of maintaining a large surface fleet.

When his pleas fell on deaf ears, he became more strident and more outspoken, believing the future of the United States to be at stake. So strong was his desire to be heard that he openly criticized his superiors, angering Army and Navy administrators and at least three presidents in the process. An abrasive and caustic man, he was court-martialed in 1925, found guilty, and suspended, essentially ending his military career…but not before organizing a demonstration that showed the potential of air superiority. Billy Mitchell died in 1936, years before he could dream of seeing his beliefs come good—but his impact on military doctrine cannot be overstated.

With this In Memoriam, we’ll be looking at the life and legacy of this complicated and controversial man.

Early Life and Career

Billy Mitchell was born on December 29th, 1879, to Wisconsin Senator John L. Mitchell and his wife Harriet. Mitchell grew up near Milwaukee, WI, and enlisted as a private at the age of 18. His father’s political influence granted young Mitchell an opportunity for a commission, and he joined the US Army Signal Corps (which develops, tests, and manages communications and information systems for the US Military) with the goal of fighting in the Spanish-American War.

Lt. Mitchell in Alaska

The war ended before he saw any action, but he stayed with the Army Signal Corps, and in 1900 was sent to the District of Alaska to oversee the establishment of a communication system to connect the many isolated outposts and gold rush camps. It was there where Mitchell, now a Lieutenant, read about the monumental glider experiments performed by Otto Lilienthal, who was the first person to document repeatable, successful flights with unpowered aircraft. These experiments had a profound impact on Mitchell, and in 1906, while an instructor at the Army Signal School in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, he gave his now-famous prediction about the future of warfare.

But it wasn’t the only of Mitchell’s predictions that came true. In 1912, upon a tour of the battlefields of the Russo-Japanese War, he concluded that war with Japan was inevitable. Later, he went so far as to predict that Japan would attack Pearl Harbor without a formal declaration of war. In this regard, Billy Mitchell was a true visionary.

In 1916, at age 37, he finally took flying private lessons at great personal expense (he was disqualified from formal military training due to age and rank). In July, 1916, he was promoted to Major and appointed Chief of the Air Services of the First Army.

WWI

Mitchell was sent to France as an observer in 1917, a task for which he was uniquely suited, thanks to his exceptional organizational and writing skills, and the fact that he spoke French. It was there where he began collaborating with senior aviation leadership from Britain and France, who taught Mitchell the basics of aerial combat strategy and major air operations. Among these was British Major General Hugh “Boom” Trenchard, himself known as “Father of the Royal Air Force,” who had been establishing the airpower playbook for years before Mitchell arrived.

At the onset of America’s entry into WWI, the Army Signal Corps Aviation Section (the “air force” then) had just over 50 aircraft, many not operational. Just a year and a half later, Billy Mitchell, now a Brigadier General, was given command of all American air units in General Pershing’s American Expeditionary Force, and orchestrated the air campaign of the Battle of St. Mihiel, coordinating nearly 1,500 Allied aircraft. What started inauspiciously ended as a major triumph—a testament to both America’s industrial prowess and to Mitchell’s exceptional command.

As Mitchell once wrote about the battle, “It was the first time in history in which an air force, cooperating with an army, was to act according to a broad strategical plan.” And it was a success. This further cemented Mitchell’s beliefs about the power of controlling the skies. “[WWI had] conclusively shown that aviation was a dominant element in the making of war, even in the relatively small way in which it was used,” he wrote.

Mitchell (left) with his gunner, leaning against a Spad aircraft

Though given his initial command because of his status, he proved to be a daring and uniquely qualified leader. For his actions, he was given the Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal.

More importantly, these successes contributed to his core belief that the Air Service had to be well-prepared at the start of the next great war, or the US could potentially lose before it ever fought.

He would spend the rest of his career working towards that preparedness…and openly challenging those who opposed.

Post-War: The Crusade Begins (1919-1921)

Mitchell knew very well that the “War to End All Wars” had accomplished something short of its moniker, and that “If a nation ambitious for universal conquest gets off to a flying start in a war of the future, it may be able to control the whole world more easily than a nation has controlled a continent in the past.”

To his horror, demobilization was the order of the day. Of the nearly 200,000 officers and men who were assigned to the Air Service at the end of the war, only 10% remained. He was appalled.

He did everything he could to prepare for the next conflict. To that end, he encouraged pilots to set world speed records to raise public consciousness. He organized long-distance air routes and simulated bombing attacks on New York. He proposed a special corps of mechanics, troop-carrying aircraft, bombers capable of transatlantic range, and—most notably—bombsights.

Mitchell in his element

But Mitchell knew that these small victories could only accomplish so much. True preparedness would require a fundamental change in thinking at the top levels of military leadership. He took every opportunity to advocate for the establishment of a separate, independent air force at the cost of spending on the surface fleet…which put him in direct conflict with US Navy leadership, notably Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt (this was the first future or sitting president Mitchell’s behavior would incense).

Understanding what Mitchell was up against requires an understanding of the Navy doctrine of the day—the Mahanian Doctrine. In 1892, Alfred Thayer Mahan, former Rear Admiral for the U.S. Navy, released his seminal work titled The Influence of Sea Power Upon the French Revolution and Empire. The book, in short, claimed that national greatness was inexorably linked with command of the sea by means of “capital ships, not too large but numerous, well-manned with crews thoroughly trained.” Mahan became world-famous, his work influencing the military elite in Great Britain, France, Japan, and here in the US.

It cannot be overstated just how pervasive Mahanian Doctrine was at the time. To those in senior leadership positions, a country’s military might was measured in battleships.

Of course, Mitchell disagreed vehemently. He maintained that expensive dreadnoughts could be easily sunk by bombs dropped from an aircraft. Mitchell faced an uphill battle. And if senior military leadership wouldn’t listen to him, he would plead his case to congress, media, public, and anyone else who would listen.

Mitchell’s beliefs can be summarized briefly:

Dreadnoughts had become obsolete, and could be destroyed easily by bombs dropped from aircraft.

There should exist an independent Air Force, equal to the Army and Navy.

A force of anti-warship airplanes could defend a coast more economically than coastal guns and naval vessels, and that the use of “floating bases” was necessary to defend the nation from naval threats.

The United States needed the ability to strike at the industrial heart of enemy powers via strategic bombing. (Please note that this is not a complete representation of his beliefs.)

The media by and large took his side, and argued that Mitchell should be allowed to conduct tests on actual warships, either captured or soon to be scuttled.

He would soon get his chance.

Project B: The Sinking of the Ostfriesland (1921)

After some pressure from the media and from congress, Secretary of War Newton Baker and Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels agreed to a demonstration, held on July 20, 1921, whereby Mitchell’s aircraft would try to sink a captured German ship called the Ostfriesland.

True to form, Mitchell oversaw every aspect of preparing, right down to the building of the one-ton bombs.

The rules of the test favored the survivability of the ship—Navy construction experts would get to examine the ship between each bombing run—but Mitchell was never one to let rules get in the way of proving his point. Directing the action from his biplane Osprey, he had his airmen bombard the Ostfriesland…and in a 20-minute period, it sank to the bottom of the sea.

Sinking of the Ostfriesland, from the US Army Air Service Photographic School

Though the results were “dubious” to some…he had broken the rules, and perhaps a well-trained damage control team could patch the hull…the captured battleship was indeed sunk by aerial bombs — a fact that was impossible to ignore.

He replicated the results by sinking the retired battleship USS Alabama in September of the same year, angering President Warren Harding (the second President to react this way to Mitchell), who didn’t want any show of weakness before the Washington Naval Conference.

A wonderful photo of the retired USS Alabama getting hit by a white phosphorous bomb

Mitchell’s campaign was tireless. To fight the status quo, he had to resort to stronger and stronger rhetoric, often agitating—even embarrassing— his superiors. “All aviation policies, schemes and systems are dictated by the non-flying officers of the Army and Navy, who know practically nothing about it,” he said publicly. He ruffled a few feathers, to say the least.

As a punishment, sr. staff sent him to Hawaiii, but he only returned with a scathing review of the lack of preparedness. Then, they sent him to Asia…but it only served to deepen his conviction that war with Japan was inevitable. These two anecdotes are very revealing of the man’s character and ambition: he knew he was being exiled, but still did his best to warn sr. leadership of vulnerabilities. This was, for all intents and purposes, classic Billy Mitchell.

When he returned in 1924, he offered yet another eerily accurate prediction: “His theory was that the military strength of the United State was so great, in Japanese eyes, that Japan could win a war only by using the most advanced methods possible. Those methods would include the extensive use of aircraft,” wrote Gen. James Doolittle in his book I Could Never Be So Lucky Again: An Autobiography.

One very important thing remains to be said about the sinking of the Ostfriesland. Just days after, Congress funded the very first aircraft carrier.

The Court-Martial (1925)

He kept crusading, and little by little, funding for aviation was increased. Still, though, leadership dragged its feet. And more airmen were paying the price. The aging aircraft were becoming dangerous to fly. A Navy plane en route to Hawaii a crashed into the sea. Two days later, a Navy dirigible over Ohio crashed. Mitchell, now especially angry, stepped up the scathing rhetoric.

In September 1925, he issued a stunning statement:

“These incidents are the direct result of the incompetency, criminal negligence, and almost treasonable administration of the national defense by the Navy and War Departments.”

This proved to be the final straw.

One month later, a charge with eight specifications was proffered against Mitchell under the 96th Article of War. This came from the direct order of President Calvin Coolidge, the third president to take umbrage at Mitchell’s methods.

Mitchell standing stoically amidst the tumult of his court-martial

Mitchell welcomed the court-martial if it forced the public to take notice.

Unsurprisingly, Mitchell was found guilty of all specifications and of the charge. He was suspended from active duty for five years without pay, which was amended by President Coolidge to half pay. Instead, he resigned on February 1st, 1926, and spent the next decade campaigning for air power to anyone he could.

Billy Mitchell died on February 19th, 1936 at the age of 56.

The Measure of a Man

Billy Mitchell’s legacy is complicated. Was he caustic and overzealous in his pursuit of a unified, separate Air Force? Yes. Was his court-martial and subsequent guilty verdict deserved? Absolutely. He was openly insubordinate to his superiors—who, by the way, were great men, American heroes.

But he was absolutely right.

Without him, we may not have been prepared to fight WWII in the air. “Many of his observations were proven during WWII, and his ultimate goal of an independent air force was realized in September 1947, over 11 years after Mitchell’s death,” wrote Lt. Col. Johnny R. Jones, USAF, in the Foreword of his compilation of Mitchell’s unpublished writings. In 1946, 10 years after his deatch

He was decades ahead of other airpower theorists of his time, and without him, who knows what the state of air services would have been in WWII? The answer to that questions…and so many others…we will never get.

Billy Mitchell was a fine commander, an exceptional coordinator, and, above all, a man of great courage who knowingly sacrificed his career to challenge the status quo and to educate politicians, policy-makers, and the public on matter of aviation. He was a visionary who saw the future of airpower so clearly that his words still ring true now. We owe him a debt we can never properly repay.

Today, we honor Major General William Lendrum “Billy” Mitchell, as we honor so many others for their sacrifices in serving our great nation. Thank you, Billy, and thank you to all those who serve and have served.

Notes

In limiting the scope of this article, I’ve done a major disservice to two men who contributed a great deal to aviation in Mitchell’s time. The first is General Benjamin Foulois, Mitchell’s chief rival and an aviator who learned to fly the first military planes purchased from the Wright Brothers. The second is Major General Mason Patrick, whose steady hand brought about the establishment of the Army Air Corps in 1926—and who often had to clean up the messes left behind in the constant sparring between Mitchell and Foulois.

It would be disingenuous to claim that everyone in senior leadership positions disagreed with Billy Mitchell. Admiral William S. Sims once said “The average man suffers very severely from the pain of a new idea…it is my belief that the future will show that the fleet that has 20 airplane carriers instead of 16 battleships and 4 airplane carriers will inevitably knock the other fleet out.”

A by-product of my decision to focus on Mitchell’s great courage in sparring with his superiors is that I haven’t done justice to his exceptional training and organizational skills. There’s a wealth of information on the subject out there on the internet; my favorite was “Billy Mitchell and the Great War, Reconsidered,” by James J. Cooke, Professor Emeritus of History, University of Mississippi.

Mitchell was a gifted writer, and his output was prodigious: more than 60 articles for publication, several newspaper series, and five books, all of which aimed to provide a “public understanding of the promise and potential of air power.” – “William ‘Billy’ Mitchell: Air Power Visionary,” C.V. Glines, Historynet.com

In 1930, Mitchell boldly predicted that his children would live to see the US go to space. Again, he was right.

Mitchell wasn’t always right. He significantly undervalued aircraft carriers, thinking them incapable of launching enough aircraft to be significant contributors to victory. He later changed course on the matter.

During the court-martial, Maj. Gen. Douglas MacArthur voted “not guilty” on the basis that a senior officer should not be silenced for disagreeing with his superiors in rank and with accepted doctrine. MacArthur later said that the order to sit on the court-martial was one of the most distasteful he ever received.

Just one more note…I’ve never served, and as hard as I have tried to get my terminology correct and not be disrespectful, I admit that I may have made a misstep. Please feel free to correct me. – Thanks

http://ift.tt/2zH7uho

0 notes

Text

In Memoriam: Billy Mitchell, Father of the United States Air Force

In Memoriam: Billy Mitchell, Father of the United States Air Force

In 1906 — two years before he witnessed a flying demonstration by Orville Wright — Billy Mitchell, an instructor at the Army Signal School, saw the future of war: in the coming years, battles would be fought and won in the air. After coming home from WWI with a reputation as a top combat airman, he campaigned for increased investment in air power at the cost of maintaining a large surface fleet.

When his pleas fell on deaf ears, he became more strident and more outspoken, believing the future of the United States to be at stake. So strong was his desire to be heard that he openly criticized his superiors, angering Army and Navy administrators and at least three presidents in the process. An abrasive and caustic man, he was court-martialed in 1925, found guilty, and suspended, essentially ending his military career…but not before organizing a demonstration that showed the potential of air superiority. Billy Mitchell died in 1936, years before he could dream of seeing his beliefs come good—but his impact on military doctrine cannot be overstated.

With this In Memoriam, we’ll be looking at the life and legacy of this complicated and controversial man.

Early Life and Career

Billy Mitchell was born on December 29th, 1879, to Wisconsin Senator John L. Mitchell and his wife Harriet. Mitchell grew up near Milwaukee, WI, and enlisted as a private at the age of 18. His father’s political influence granted young Mitchell an opportunity for a commission, and he joined the US Army Signal Corps (which develops, tests, and manages communications and information systems for the US Military) with the goal of fighting in the Spanish-American War.

Lt. Mitchell in Alaska

The war ended before he saw any action, but he stayed with the Army Signal Corps, and in 1900 was sent to the District of Alaska to oversee the establishment of a communication system to connect the many isolated outposts and gold rush camps. It was there where Mitchell, now a Lieutenant, read about the monumental glider experiments performed by Otto Lilienthal, who was the first person to document repeatable, successful flights with unpowered aircraft. These experiments had a profound impact on Mitchell, and in 1906, while an instructor at the Army Signal School in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, he gave his now-famous prediction about the future of warfare.

But it wasn’t the only of Mitchell’s predictions that came true. In 1912, upon a tour of the battlefields of the Russo-Japanese War, he concluded that war with Japan was inevitable. Later, he went so far as to predict that Japan would attack Pearl Harbor without a formal declaration of war. In this regard, Billy Mitchell was a true visionary.

In 1916, at age 37, he finally took flying private lessons at great personal expense (he was disqualified from formal military training due to age and rank). In July, 1916, he was promoted to Major and appointed Chief of the Air Services of the First Army.

WWI

Mitchell was sent to France as an observer in 1917, a task for which he was uniquely suited, thanks to his exceptional organizational and writing skills, and the fact that he spoke French. It was there where he began collaborating with senior aviation leadership from Britain and France, who taught Mitchell the basics of aerial combat strategy and major air operations. Among these was British Major General Hugh “Boom” Trenchard, himself known as “Father of the Royal Air Force,” who had been establishing the airpower playbook for years before Mitchell arrived.

At the onset of America’s entry into WWI, the Army Signal Corps Aviation Section (the “air force” then) had just over 50 aircraft, many not operational. Just a year and a half later, Billy Mitchell, now a Brigadier General, was given command of all American air units in General Pershing’s American Expeditionary Force, and orchestrated the air campaign of the Battle of St. Mihiel, coordinating nearly 1,500 Allied aircraft. What started inauspiciously ended as a major triumph—a testament to both America’s industrial prowess and to Mitchell’s exceptional command.

As Mitchell once wrote about the battle, “It was the first time in history in which an air force, cooperating with an army, was to act according to a broad strategical plan.” And it was a success. This further cemented Mitchell’s beliefs about the power of controlling the skies. “[WWI had] conclusively shown that aviation was a dominant element in the making of war, even in the relatively small way in which it was used,” he wrote.

Mitchell (left) with his gunner, leaning against a Spad aircraft

Though given his initial command because of his status, he proved to be a daring and uniquely qualified leader. For his actions, he was given the Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal.

More importantly, these successes contributed to his core belief that the Air Service had to be well-prepared at the start of the next great war, or the US could potentially lose before it ever fought.

He would spend the rest of his career working towards that preparedness…and openly challenging those who opposed.

Post-War: The Crusade Begins (1919-1921)

Mitchell knew very well that the “War to End All Wars” had accomplished something short of its moniker, and that “If a nation ambitious for universal conquest gets off to a flying start in a war of the future, it may be able to control the whole world more easily than a nation has controlled a continent in the past.”

To his horror, demobilization was the order of the day. Of the nearly 200,000 officers and men who were assigned to the Air Service at the end of the war, only 10% remained. He was appalled.

He did everything he could to prepare for the next conflict. To that end, he encouraged pilots to set world speed records to raise public consciousness. He organized long-distance air routes and simulated bombing attacks on New York. He proposed a special corps of mechanics, troop-carrying aircraft, bombers capable of transatlantic range, and—most notably—bombsights.

Mitchell in his element

But Mitchell knew that these small victories could only accomplish so much. True preparedness would require a fundamental change in thinking at the top levels of military leadership. He took every opportunity to advocate for the establishment of a separate, independent air force at the cost of spending on the surface fleet…which put him in direct conflict with US Navy leadership, notably Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt (this was the first future or sitting president Mitchell’s behavior would incense).

Understanding what Mitchell was up against requires an understanding of the Navy doctrine of the day—the Mahanian Doctrine. In 1892, Alfred Thayer Mahan, former Rear Admiral for the U.S. Navy, released his seminal work titled The Influence of Sea Power Upon the French Revolution and Empire. The book, in short, claimed that national greatness was inexorably linked with command of the sea by means of “capital ships, not too large but numerous, well-manned with crews thoroughly trained.” Mahan became world-famous, his work influencing the military elite in Great Britain, France, Japan, and here in the US.

It cannot be overstated just how pervasive Mahanian Doctrine was at the time. To those in senior leadership positions, a country’s military might was measured in battleships.

Of course, Mitchell disagreed vehemently. He maintained that expensive dreadnoughts could be easily sunk by bombs dropped from an aircraft. Mitchell faced an uphill battle. And if senior military leadership wouldn’t listen to him, he would plead his case to congress, media, public, and anyone else who would listen.

Mitchell’s beliefs can be summarized briefly:

Dreadnoughts had become obsolete, and could be destroyed easily by bombs dropped from aircraft.

There should exist an independent Air Force, equal to the Army and Navy.

A force of anti-warship airplanes could defend a coast more economically than coastal guns and naval vessels, and that the use of “floating bases” was necessary to defend the nation from naval threats.

The United States needed the ability to strike at the industrial heart of enemy powers via strategic bombing. (Please note that this is not a complete representation of his beliefs.)

The media by and large took his side, and argued that Mitchell should be allowed to conduct tests on actual warships, either captured or soon to be scuttled.

He would soon get his chance.

Project B: The Sinking of the Ostfriesland (1921)

After some pressure from the media and from congress, Secretary of War Newton Baker and Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels agreed to a demonstration, held on July 20, 1921, whereby Mitchell’s aircraft would try to sink a captured German ship called the Ostfriesland.

True to form, Mitchell oversaw every aspect of preparing, right down to the building of the one-ton bombs.

The rules of the test favored the survivability of the ship—Navy construction experts would get to examine the ship between each bombing run—but Mitchell was never one to let rules get in the way of proving his point. Directing the action from his biplane Osprey, he had his airmen bombard the Ostfriesland…and in a 20-minute period, it sank to the bottom of the sea.

Sinking of the Ostfriesland, from the US Army Air Service Photographic School

Though the results were “dubious” to some…he had broken the rules, and perhaps a well-trained damage control team could patch the hull…the captured battleship was indeed sunk by aerial bombs — a fact that was impossible to ignore.

He replicated the results by sinking the retired battleship USS Alabama in September of the same year, angering President Warren Harding (the second President to react this way to Mitchell), who didn’t want any show of weakness before the Washington Naval Conference.

A wonderful photo of the retired USS Alabama getting hit by a white phosphorous bomb

Mitchell’s campaign was tireless. To fight the status quo, he had to resort to stronger and stronger rhetoric, often agitating—even embarrassing— his superiors. “All aviation policies, schemes and systems are dictated by the non-flying officers of the Army and Navy, who know practically nothing about it,” he said publicly. He ruffled a few feathers, to say the least.

As a punishment, sr. staff sent him to Hawaiii, but he only returned with a scathing review of the lack of preparedness. Then, they sent him to Asia…but it only served to deepen his conviction that war with Japan was inevitable. These two anecdotes are very revealing of the man’s character and ambition: he knew he was being exiled, but still did his best to warn sr. leadership of vulnerabilities. This was, for all intents and purposes, classic Billy Mitchell.

When he returned in 1924, he offered yet another eerily accurate prediction: “His theory was that the military strength of the United State was so great, in Japanese eyes, that Japan could win a war only by using the most advanced methods possible. Those methods would include the extensive use of aircraft,” wrote Gen. James Doolittle in his book I Could Never Be So Lucky Again: An Autobiography.

One very important thing remains to be said about the sinking of the Ostfriesland. Just days after, Congress funded the very first aircraft carrier.

The Court-Martial (1925)

He kept crusading, and little by little, funding for aviation was increased. Still, though, leadership dragged its feet. And more airmen were paying the price. The aging aircraft were becoming dangerous to fly. A Navy plane en route to Hawaii a crashed into the sea. Two days later, a Navy dirigible over Ohio crashed. Mitchell, now especially angry, stepped up the scathing rhetoric.

In September 1925, he issued a stunning statement:

“These incidents are the direct result of the incompetency, criminal negligence, and almost treasonable administration of the national defense by the Navy and War Departments.”

This proved to be the final straw.

One month later, a charge with eight specifications was proffered against Mitchell under the 96th Article of War. This came from the direct order of President Calvin Coolidge, the third president to take umbrage at Mitchell’s methods.

Mitchell standing stoically amidst the tumult of his court-martial

Mitchell welcomed the court-martial if it forced the public to take notice.

Unsurprisingly, Mitchell was found guilty of all specifications and of the charge. He was suspended from active duty for five years without pay, which was amended by President Coolidge to half pay. Instead, he resigned on February 1st, 1926, and spent the next decade campaigning for air power to anyone he could.

Billy Mitchell died on February 19th, 1936 at the age of 56.

The Measure of a Man

Billy Mitchell’s legacy is complicated. Was he caustic and overzealous in his pursuit of a unified, separate Air Force? Yes. Was his court-martial and subsequent guilty verdict deserved? Absolutely. He was openly insubordinate to his superiors—who, by the way, were great men, American heroes.

But he was absolutely right.

Without him, we may not have been prepared to fight WWII in the air. “Many of his observations were proven during WWII, and his ultimate goal of an independent air force was realized in September 1947, over 11 years after Mitchell’s death,” wrote Lt. Col. Johnny R. Jones, USAF, in the Foreword of his compilation of Mitchell’s unpublished writings. In 1946, 10 years after his deatch

He was decades ahead of other airpower theorists of his time, and without him, who knows what the state of air services would have been in WWII? The answer to that questions…and so many others…we will never get.

Billy Mitchell was a fine commander, an exceptional coordinator, and, above all, a man of great courage who knowingly sacrificed his career to challenge the status quo and to educate politicians, policy-makers, and the public on matter of aviation. He was a visionary who saw the future of airpower so clearly that his words still ring true now. We owe him a debt we can never properly repay.

Today, we honor Major General William Lendrum “Billy” Mitchell, as we honor so many others for their sacrifices in serving our great nation. Thank you, Billy, and thank you to all those who serve and have served.

Notes

In limiting the scope of this article, I’ve done a major disservice to two men who contributed a great deal to aviation in Mitchell’s time. The first is General Benjamin Foulois, Mitchell’s chief rival and an aviator who learned to fly the first military planes purchased from the Wright Brothers. The second is Major General Mason Patrick, whose steady hand brought about the establishment of the Army Air Corps in 1926—and who often had to clean up the messes left behind in the constant sparring between Mitchell and Foulois.

It would be disingenuous to claim that everyone in senior leadership positions disagreed with Billy Mitchell. Admiral William S. Sims once said “The average man suffers very severely from the pain of a new idea…it is my belief that the future will show that the fleet that has 20 airplane carriers instead of 16 battleships and 4 airplane carriers will inevitably knock the other fleet out.”

A by-product of my decision to focus on Mitchell’s great courage in sparring with his superiors is that I haven’t done justice to his exceptional training and organizational skills. There’s a wealth of information on the subject out there on the internet; my favorite was “Billy Mitchell and the Great War, Reconsidered,” by James J. Cooke, Professor Emeritus of History, University of Mississippi.