#brainslide bedrock education talk

Text

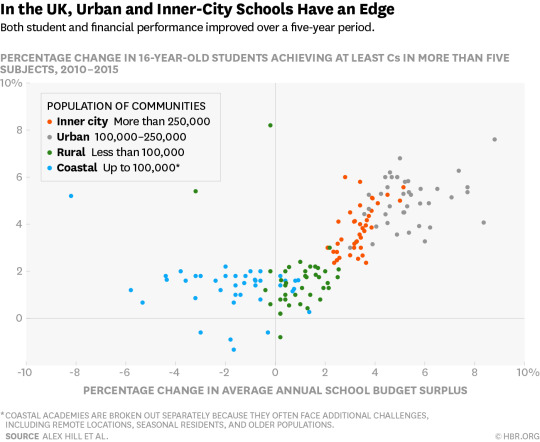

How to Turn Around a Failing School

To say that school reforms are a contested area is something of an understatement. There are some strongly held opinions in education about what improves a school, such as raising teaching standards and reducing class sizes.

Our findings challenge some of these beliefs. To understand how to turn around a failing school quickly, using as few resources as possible, we studied changes made by 160 UK academies after they were put into remedial measures by the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (OFSTED) up to seven years ago. (In the UK, an academy is a publicly funded school or group of schools. One school can acquire others to form a group, which shares resources, making investment easier and cuts less painful. Academies have devolved decision-making powers, bypassing local government.)

This provided us with the rare opportunity to look at a large number of organizations which all:

Are regulated, documented, and measured in the same way

Provide a similar service

Have made similar changes

However, each academy:

Made these changes in a different order

Operated in regions with different levels of competition and access to resources

This is research gold, as it’s possible to isolate variables and understand the impact of changing them. For example, we were able to say 30 academies made X change, while 40 didn’t, and then draw conclusions from the differing outcomes. We could analyze the effects of 58 types of investment, on 18 performance measures over time, in 160 academies operating in 18 different regions. We were given full access to the academies’ management information systems, leaders, staff and students so we could see how they worked, the decisions they’d made and the impact they’d had.

So what did we find? Like any turnaround, there is no magic bullet — a series of remedial steps need to be taken. And each step’s impact depends and builds on the previous steps in the sequence, as well the school’s location, because the latter determines access to good leaders, teachers, and students.

Here are recommendations based on the effective (and ineffective) practices we uncovered:

Don’t improve teaching first. This was a very common mistake. Many schools tried to improve teaching while still struggling with badly behaving students, operating across a number of sites or having a poor head of school in charge. You can’t expect teachers to sort out all the problems themselves — you need to create the right environment first.

Do improve governance, leadership, and structures first. Otherwise, you’re putting great teachers in a position where they fail — they’ll waste time doing or managing the wrong things.

Don’t reduce class sizes. While reducing class size works, it is not the best use of resources. It is expensive and you can create the same impact by improving student motivation and behavior, which takes fewer resources. We found class sizes of 30 performed as well as class sizes of 15, when standards of student behavior had been addressed first.

Do improve student behavior and motivation. The best way to create the right environment for good teachers is to improve student behavior and motivation. Controversially, we found that the fastest way to do this is to exclude poorly behaved students: Pay other schools to teach them or, as most academies did, build a new, smaller school for these students. However, while this “quick win” produced immediate results, it was not the best long-term solution (and indeed, it’s probably not the best solution for society either). The better, more sustainable practice was to move poorly behaved students into another pathway within the existing school, so that they can be managed differently and reintegrated into the main pathway once their behavior has improved.

Don’t use a “zero tolerance” policy. Many schools tried to come down hard on poor behavior with a “zero tolerance” policy. However, the short term, positive impact didn’t last and in some cases, students revolted and even rioted.

Do create an “all through” school. Keep students from the age of five until they leave at ages 16 or 18. In this way, school leaders can create the right culture early on and ensure that poor behaviors never develop. It also makes teaching at secondary school level (age 11 up) much easier, as you don’t have to integrate older students with different views about standards.

Don’t use a super head. Many academies parachuted in a “super head” from a successful school to turn themselves around. Although this had a positive short-term impact, it didn’t create the right foundations for sustainable long-term improvement. These “super heads” tended to be involved only for one to two years and focused their changes on the school year (ages 15–16) and subjects (mathematics and english) used to assess performance, so they could make quick improvements, take the credit, and move on.

In every case, exam results dipped after the “super head” left and only started improving three years later. The new head spent up to $2 million cleaning up the mess created by diverting attention, resources, and teaching capability from other age groups and subjects.

Do improve all year groups. Although schools can improve short-term performance by cutting and reallocating resources, they will not create sustainable improvement unless they invest in all age groups and subjects.

Don’t expect inner city schools to be more difficult. Another common view is that it is more difficult to turn around an inner city school. However, we found it is easier, as they have greater access to good leaders, teachers, and students.

Do invest more in rural and coastal schools. It is more difficult to attract good leaders, teachers and students in rural and coastal areas. Improvement was much slower in these regions.

Don’t expect spending more money to solve your school’s problems any faster… More resources can help to overcome specific challenges, such as attracting good leaders and teachers, but at least in these 160 British academies, what mattered most to the overall speed of improvement was making the right changes in the right order.

…But, at the same time, don’t expect to improve without spending more, at least in the short term. To improve student learning, schools must have the basic resources they need to improve student behavior, pay higher salaries to attract good teachers, and employ staff to manage parents so teachers can spend more time teaching and leaders can spend more time leading. Expect financial performance to dip in the short-term. Pursuing financial performance over operational performance will not serve students well in the long term.

There are three key learnings from this research. First, you need to create the right environment before improving teaching standards. Great teaching is wasted without the right governance, leadership, and structures, with well-behaved students.

Second, the most significant improvement occurred when schools changed their students by excluding poor behavior, creating multiple pathways for students with differing needs and creating a school for ages five through 16–18. This change consistently improved performance more than any other.

Third, you have to plan for a dip in financial performance before your exam results will improve. You either need to part of a larger group (such as a multiacademy trust) with access to the resources you need to get through this dip. Or, acquire another school early on in your journey to increase your revenue and spread your costs across a larger number of students.

Source: Harvard Business Review / Alex Hill,

Liz Mellon, Jules Goddard and Ben Laker.

Link: Turn Around a Failing School

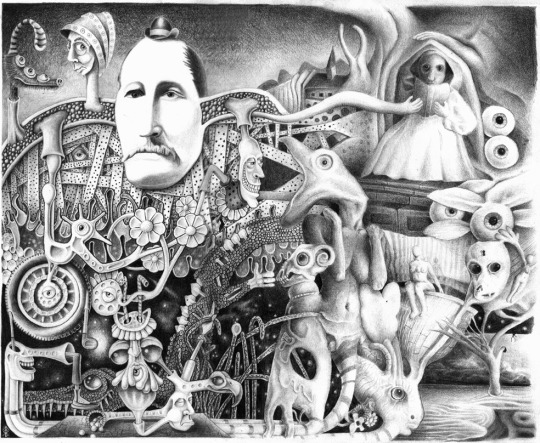

Illustration: Øivind Hovland - "Skoleforfall".

Moderator: ART HuNTER.

#propaganda#neoliberal capitalism#postmodern thinking#contemporary world#education#knowledge#article#harvard business review#Øivind hovland#brainslide bedrock education talk#free your mind

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lifelong Learning Is Good for Your Health, Your Wallet, and Your Social Life

In 2015 Doreetha Daniels received her associate degree in social sciences from College of the Canyons, in Santa Clarita, California. But Daniels wasn’t a typical student: She was 99 years old. In the COC press release about her graduation, Daniels indicated that she wanted to get her degree simply to better herself; her six years of school during that pursuit were a testament to her will, determination, and commitment to learning.

Few of us will pursue college degrees as nonagenarians, or even as mid-career professionals (though recent statistics indicate that increasing numbers of people are pursuing college degrees at advanced ages). Some people never really liked school in the first place, sitting still at a desk for hours on end or suffering through what seemed to be impractical courses. And almost all of us have limits on our time and finances — due to kids, social organizations, work, and more — that make additional formal education impractical or impossible.

As we age, though, learning isn’t simply about earning degrees or attending storied institutions. Books, online courses, MOOCs, professional development programs, podcasts, and other resources have never been more abundant or accessible, making it easier than ever to make a habit of lifelong learning. Every day, each of us is offered the opportunity to pursue intellectual development in ways that are tailored to our learning style.

So why don’t more of us seize that opportunity? We know it’s worth the time, and yet we find it so hard to make the time. The next time you’re tempted to put learning on the back burner, remember a few points:

Educational investments are an economic imperative.

The links between formal education and lifetime earnings are well-studied and substantial. In 2015 Christopher Tamborini, ChangHwan Kim, and Arthur Sakamoto found that, controlling for other factors, men and women can expect to earn $655,000 and $445,000 more, respectively, during their careers with a bachelor’s degree than with a high school degree, and graduate degrees yield further gains. Outside of universities, ongoing learning and skill development is essential to surviving economic and technological disruption. The Economist recently detailed the ways in which our rapidly shifting professional landscape — the disruptive power of automation, the increasing number of jobs requiring expertise in coding — necessitates that workers focus continually on mastering new technologies and skills. In 2014 a CBRE report estimated that 50% of jobs would be redundant by 2025 due to technological innovation. Even if that figure proves to be exaggerated, it’s intuitively true that the economic landscape of 2017 is evolving more rapidly than in the past. Trends including AI, robotics, and offshoring mean constant shifts in the nature of work. And navigating this ever-changing landscape requires continual learning and personal growth.

Learning is positive for health.

As I’ve noted previously, reading, even for short periods of time, can dramatically reduce your stress levels. A recent report in Neurology noted that while cognitive activity can’t change the biology of Alzheimer’s, learning activities can help delay symptoms, preserving people’s quality of life. Other research indicates that learning to play a new instrument can offset cognitive decline, and learning difficult new skills in older age is associated with improved memory.

What’s more, while the causation is inconclusive, there’s a well-studied relationship between longevity and education. A 2006 paper by David Cutler and Adriana Lleras-Muney found that “the better educated have healthier behaviors along virtually every margin, although some of these behaviors may also reflect differential access to care.” Their research suggests that a year of formal education can add more than half a year to a person’s life span. Perhaps Doreetha Daniels, at 99, knows something many of us have missed.

Being open and curious has profound personal and professional benefits.

While few studies validate this observation, I’ve noticed in my own interactions that those who dedicate themselves to learning and who exhibit curiosity are almost always happier and more socially and professionally engaging than those who don’t. I have a friend, Duncan, for example, who is almost universally admired by people he interacts with. There are many reasons for this admiration, but chief among them are his plainly exhibited intellectual curiosity and his ability to touch, if only briefly, on almost any topic of interest to others and to speak deeply on those he knows best. Think of the best conversationalist you know. Do they ask good questions? Are they well-informed? Now picture the colleague you most respect for their professional acumen. Do they seem literate, open-minded, and intellectually vibrant? Perhaps your experiences will differ, but if you’re like me, I suspect those you admire most, both personally and professionally, are those who seem most dedicated to learning and growth.

Our capacity for learning is a cornerstone of human flourishing and motivation.

We are uniquely endowed with the capacity for learning, creation, and intellectual advancement. Have you ever sat in a quiet place and finished a great novel in one sitting? Do you remember the fulfillment you felt when you last settled into a difficult task — whether a math problem or a foreign language course — and found yourself making breakthrough progress? Have you ever worked with a team of friends or colleagues to master difficult material or create something new? These experiences can be electrifying. And even if education had no impact on health, prosperity, or social standing, it would be entirely worthwhile as an expression of what makes every person so special and unique.

The reasons to continue learning are many, and the weight of the evidence would indicate that lifelong learning isn’t simply an economic imperative but a social, emotional, and physical one as well. We live in an age of abundant opportunity for learning and development. Capturing that opportunity — maintaining our curiosity and intellectual humility — can be one of life’s most rewarding pursuits.

Source: Harvard Business Review / John Coleman.

Link: Lifelong Learning Is Good

Illustration: Laurie Lipton.

Moderator: ART HuNTER.

#propaganda#neoliberal capitalism#contemporary world#postmodern thinking#economy#education#knowledge#brainslide bedrock education talk#harvard business review#laurie lipton#free your mind

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

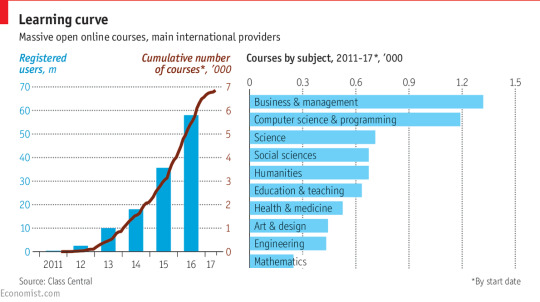

Established education providers v new contenders

THE HYPE OVER MOOCs peaked in 2012. Salman Khan, an investment analyst who had begun teaching bite-sized lessons to his cousin in New Orleans over the internet and turned that activity into a wildly popular educational resource called the Khan Academy, was splashed on the cover of Forbes. Sebastian Thrun, the founder of another MOOC called Udacity, predicted in an interview in Wired magazine that within 50 years the number of universities would collapse to just ten worldwide. The New York Times declared it the year of the MOOC.

The sheer numbers of people flocking to some of the initial courses seemed to suggest that an entirely new model of open-access, free university education was within reach. Now MOOC sceptics are more numerous than believers. Although lots of people still sign up, drop-out rates are sky-high.

Nonetheless, the MOOCs are on to something. Education, like health care, is a complex and fragmented industry, which makes it hard to gain scale. Despite those drop-out rates, the MOOCs have shown it can be done quickly and comparatively cheaply. The Khan Academy has 14m-15m users who conduct at least one learning activity with it each month; Coursera has 22m registered learners. Those numbers are only going to grow. FutureLearn, a MOOC owned by Britain’s Open University, has big plans. Oxford University announced in November that it would be producing its first MOOC on the edX platform.

In their search for a business model, some platforms are now focusing much more squarely on employment (though others, like the Khan Academy, are not for profit). Udacity has launched a series of nanodegrees in tech-focused courses that range from the basic to the cutting-edge. It has done so, moreover, in partnership with employers. A course on Android was developed with Google; a nanodegree in self-driving cars uses instructors from Mercedes-Benz, Nvidia and others. Students pay $199-299 a month for as long as it takes them to finish the course (typically six to nine months) and get a 50% rebate if they complete it within a year. Udacity also offers a souped-up version of its nanodegree for an extra $100 a month, along with a money-back guarantee if graduates do not find a job within six months.

Coursera’s content comes largely from universities, not specialist instructors; its range is much broader; and it is offering full degrees (one in computer science, the other an MBA) as well as shorter courses. But it, too, has shifted its emphasis to employability. Its boss, Rick Levin, a former president of Yale University, cites research showing that half of its learners took courses in order to advance their careers. Although its materials are available without charge, learners pay for assessment and accreditation at the end of the course ($300-400 for a four-course sequence that Coursera calls a “specialisation”). It has found that when money is changing hands, completion rates rise from 10% to 60% . It is increasingly working with companies, too. Firms can now integrate Coursera into their own learning portals, track employees’ participation and provide their desired menu of courses.

These are still early days. Coursera does not give out figures on its paying learners; Udacity says it has 13,000 people doing its nanodegrees. Whatever the arithmetic, the reinvented MOOCs matter because they are solving two problems they share with every provider of later-life education.

The first of these is the cost of learning, not just in money but also in time. Formal education rests on the idea of qualifications that take a set period to complete. In America the entrenched notion of “seat time”, the amount of time that students spend with school teachers or university professors, dates back to Andrew Carnegie. It was originally intended as an eligibility requirement for teachers to draw a pension from the industrialist’s nascent pension scheme for college faculty. Students in their early 20s can more easily afford a lengthy time commitment because they are less likely to have other responsibilities. Although millions of people do manage part-time or distance learning in later life—one-third of all working students currently enrolled in America are 30-54 years old, according to the Georgetown University Centre on Education and the Workforce—balancing learning, working and family life can cause enormous pressures.

Moreover, the world of work increasingly demands a quick response from the education system to provide people with the desired qualifications. To take one example from Burning Glass, in 2014 just under 50,000 American job-vacancy ads asked for a CISSP cyber-security certificate. Since only 65,000 people in America hold such a certificate and it takes five years of experience to earn one, that requirement will be hard to meet. Less demanding professions also put up huge barriers to entry. If you want to become a licensed cosmetologist in New Hampshire, you will need to have racked up 1,500 hours of training.

In response, the MOOCs have tried to make their content as digestible and flexible as possible. Degrees are broken into modules; modules into courses; courses into short segments. The MOOCs test for optimal length to ensure people complete the course; six minutes is thought to be the sweet spot for online video and four weeks for a course.

Scott DeRue, the dean of the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan, says the unbundling of educational content into smaller components reminds him of another industry: music. Songs used to be bundled into albums before being disaggregated by iTunes and streaming services such as Spotify. In Mr DeRue’s analogy, the degree is the album, the course content that is freely available on MOOCs is the free streaming radio service, and a “microcredential” like the nanodegree or the specialisation is paid-for iTunes.

How should universities respond to that kind of disruption? For his answer, Mr DeRue again draws on the lessons of the music industry. Faced with the disruption caused by the internet, it turned to live concerts, which provided a premium experience that cannot be replicated online. The on-campus degree also needs to mark itself out as a premium experience, he says.

Another answer is for universities to make their own products more accessible by doing more teaching online. This is beginning to happen. When Georgia Tech decided to offer an online version of its masters in computer science at low cost, many were shocked: it seemed to risk cannibalising its campus degree. But according to Joshua Goodman of Harvard University, who has studied the programme, the decision was proved right. The campus degree continued to recruit students in their early 20s whereas the online degree attracted people with a median age of 34 who did not want to leave their jobs. Mr Goodman reckons this one programme could boost the numbers of computer-science masters produced in America each year by 7-8%. Chip Paucek, the boss of 2U, a firm that creates online degree programmes for conventional universities, reports that additional marketing efforts to lure online students also boost on-campus enrolments.

Educational Lego

Universities can become more modular, too. EdX has a micromasters in supply-chain management that can either be taken on its own or count towards a full masters at MIT. The University of Wisconsin-Extension has set up a site called the University Learning Store, which offers slivers of online content on practical subjects such as project management and business writing. Enthusiasts talk of a world of “stackable credentials” in which qualifications can be fitted together like bits of Lego.

Just how far and fast universities will go in this direction is unclear, however. Degrees are still highly regarded, and increased emphasis on critical thinking and social skills raises their value in many ways. “The model of campuses, tenured faculty and so on does not work that well for short courses,” adds Jake Schwartz, General Assembly’s boss. “The economics of covering fixed costs forces them to go longer.”

Academic institutions also struggle to deliver really fast-moving content. Pluralsight uses a model similar to that of book publishing by employing a network of 1,000 experts to produce and refresh its library of videos on IT and creative skills. These experts get royalties based on how often their content is viewed; its highest earner pulled in $2m last year, according to Aaron Skonnard, the firm’s boss. Such rewards provide an incentive for authors to keep updating their content. University faculty have other priorities.

People are more likely to invest in training if it confers a qualification that others will recognise. But they also need to know which skills are useful in the first place

Beside costs, the second problem for MOOCs to solve is credentials. Close colleagues know each other’s abilities, but modern labour markets do not work on the basis of such relationships. They need widely understood signals of experience and expertise, like a university degree or a baccalaureate, however imperfect they may be. In their own fields, vocational qualifications do the same job. The MOOCs’ answer is to offer microcredentials like nanodegrees and specialisations.

But employers still need to be confident that the skills these credentials vouchsafe are for real. LinkedIn’s “endorsements” feature, for example, was routinely used by members to hand out compliments to people they did not know for skills they did not possess, in the hope of a reciprocal recommendation. In 2016 the firm tightened things up, but getting the balance right is hard. Credentials require just the right amount of friction: enough to be trusted, not so much as to block career transitions.

Universities have no trouble winning trust: many of them can call on centuries of experience and name recognition. Coursera relies on universities and business schools for most of its content; their names sit proudly on the certificates that the firm issues. Some employers, too, may have enough kudos to play a role in authenticating credentials. The involvement of Google in the Android nanodegree has helped persuade Flipkart, an Indian e-commerce platform, to hire Udacity graduates sight unseen.

Wherever the content comes from, students’ work usually needs to be validated properly for a credential to be trusted. When student numbers are limited, the marking can be done by the teacher. But in the world of MOOCs those numbers can spiral, making it impractical for the instructors to do all the assessments. Automation can help, but does not work for complex assignments and subjects. Udacity gets its students to submit their coding projects via GitHub, a hosting site, to a network of machine-learning graduates who give feedback within hours.

Even if these problems can be overcome, however, there is something faintly regressive about the world of microcredentials. Like a university degree, it still involves a stamp of approval from a recognised provider after a proprietary process. Yet lots of learning happens in informal and experiential settings, and lots of workplace skills cannot be acquired in a course.

Gold stars for good behaviour

One way of dealing with that is to divide the currency of knowledge into smaller denominations by issuing “digital badges” to recognise less formal achievements. RMIT University, Australia’s largest tertiary-education institution, is working with Credly, a credentialling platform, to issue badges for the skills that are not tested in exams but that firms nevertheless value. Belinda Tynan, RMIT’s vice-president, cites a project carried out by engineering students to build an electric car, enter it into races and win sponsors as an example.

The trouble with digital badges is that they tend to proliferate. Illinois State University alone created 110 badges when it launched a programme with Credly in 2016. Add in MOOC certificates, LinkedIn Learning courses, competency-based education, General Assembly and the like, and the idea of creating new currencies of knowledge starts to look more like a recipe for hyperinflation.

David Blake, the founder of Degreed, a startup, aspires to resolve that problem by acting as the central bank of credentials. He wants to issue a standardised assessment of skill levels, irrespective of how people got there. The plan is to create a network of subject-matter experts to assess employees’ skills (copy-editing, say, or credit analysis), and a standardised grading language that means the same thing to everyone, everywhere.

Pluralsight is heading in a similar direction in its field. A diagnostic tool uses a technique called item response theory to work out users’ skill levels in areas such as coding, giving them a rating. The system helps determine what individuals should learn next, but also gives companies a standardised way to evaluate people’s skills.

A system of standardised skills measures has its own problems, however. Using experts to grade ability raises recursive questions about the credentials of those experts. And it is hard for item response theory to assess subjective skills, such as an ability to construct an argument. Specific, measurable skills in areas such as IT are more amenable to this approach.

So amenable, indeed, that they can be tested directly. As an adolescent in Armenia, Tigran Sloyan used to compete in mathematical Olympiads. That experience helped him win a place at MIT and also inspired him to found a startup called CodeFights in San Francisco. The site offers free gamified challenges to 500,000 users as a way of helping programmers learn. When they know enough, they are funnelled towards employers, which pay the firm 15% of a successful candidate’s starting salary. Sqore, a startup in Stockholm, also uses competitions to screen job applicants on behalf of its clients.

However it is done, the credentialling problem has to be solved. People are much more likely to invest in training if it confers a qualification that others will recognise. But they also need to know which skills are useful in the first place.

Source: The Economist / Special report.

Link: Established education providers v new contenders

Illustration: Brad Holland.

Moderator: ART HuNTER.

#propaganda#neoliberal capitalism#postmodern thinking#contemporary world#education#technology#knowledge#brainslide bedrock education talk#the economist#brad holland#article#free your mind

1 note

·

View note

Text

Stop Requiring College Degrees (Harvard Business Review)

If you’re an employer, there are lots of signals about a young person’s suitability for the job you’re offering. If you’re looking for someone who can write, do they have a blog, or are they a prolific Wikipedia editor? For programmers, what are their TopCoder or GitHub scores? For salespeople, what have they sold before? If you want general hustle, do they have a track record of entrepreneurship, or at least holding a series of jobs?

These days, there are also a range of tests you can administer to prospective employees to see if they’re right for the job. Some of them are pretty straightforward. Others, like Knack, seek to test for attributes that might seem unrelated, but have been shown by prior experience to be associated with good on-the-job performance.

And there’s been a recent explosion in MOOCs — massive, open, online courses, many of them free — on a wide range of subjects. Many of these evaluate their students via a final exam or other means, and so provide a signal about how well someone mastered the material. MOOCs are still quite young so it’s not clear how accurate their evaluations are, but I’m encouraged by what I’ve seen so far. I’d give serious consideration to a job seeker who had taken a bunch of MOOCs and done well in all of them.

You’ve noticed by now that ‘a college degree’ is not in this list of signals. That’s because I think it’s a pretty lousy one, and getting worse all the time. In fact, I think one of the most productive things an employer could do, both for themselves and for society at large, is to stop placing so much emphasis on standard undergraduate and graduate degrees.

Unfortunately, employers are doing exactly the opposite — they’re putting more emphasis over time on old-school degrees, not less. As a recent New York Times story put it, “The college degree is becoming the new high school diploma: the new minimum requirement, albeit an expensive one, for getting even the lowest-level job.” Dental lab techs, chemical equipment tenders, and medical equipment preparers are all jobs that require a degree at least 50% more often than they used to as recently as 2007.

There are two huge problems with this approach. One is that college is really expensive, and getting more so all the time. According to figures compiled by Jared Bernstein, while median income for two-parent, two-child families went up by 20% between 1990 and 2008, the cost of a four-year public college education went up by three times that amount. Total student loan debt is now larger than credit card debt in the US, and it can’t be discharged even in bankruptcy. As a 2011 graduate working as a receptionist put it in the Times article, “I am over $100,000 in student loan debt right now… I will probably never see the end of that bill”

The even bigger problem is that, as I mentioned above, I believe college degrees are getting less valuable over time even as they’re getting more expensive. There’s a lot of evidence piling up about what’s happening with actual learning on campuses these days, and most of it is not pretty. Fewer students are entering the tougher STEM majors and completing degrees in them, even though graduates in these fields are much in demand. It’s taking students longer to complete their degrees, and dropout rates are rising. The most alarming and depressing stats I’ve come across are that 45% of college students didn’t seem to learn much of anything during their first two years, and as many as 36% showed no improvement after four years. Whatever’s going on with these kids at these schools, it’s not education.

I think what’s going on in my home industry of higher education at present is something between a bubble and a scandal. And I don’t think it’ll change unless and until employers shift, and start valuing signals other than college degrees. I can’t think of a single good reason not to start that shift now. Can you?

Source: Harvard Business Review / Andrew McAfee.

Link: Stop Requiring College Degrees

Illustration: David Plunkert - Power(less) of Attorney.

Moderator: ART HuNTER.

#contemporary world#postmodern thinking#neoliberal capitalism#critical thinking#economy#education#brainslide bedrock education talk#knowledge#david plunkert#harvard business review#propaganda#article#free your mind

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some say bypassing a higher education is smarter than paying for a degree (Washington Post)

Across the region and around the country, parents are kissing their college-bound kids -- and potentially up to $200,000 in tuition, room and board -- goodbye.

Especially in the supremely well-educated Washington area, this is expected. It's a rite of passage, part of an orderly progression toward success.

Or is it . . . herd mentality?

Hear this, high achievers: If you crunch the numbers, some experts say, college is a bad investment.

"You've been fooled into thinking there's no other way for my kid to get a job . . . or learn critical thinking or make social connections," hedge fund manager James Altucher says.

Altucher, president of Formula Capital, says he sees people making bad investment decisions all the time -- and one of them is paying for college.

College is overrated, he says: In most cases, what you get out of it is not worth the money, and there are cheaper and better ways to get an education. Altucher says he's not planning to send his two daughters to college.

"My plan is to encourage them to pursue a dream, at least initially," Altucher, 42, says. "Travel or do something creative or start a business. . . . Whether they succeed or fail, it'll be an interesting life experience. They'll meet people, they'll learn the value of money."

Certainly, you'd be forgiven for thinking this argument reeks of elitism. After all, Altucher is an Ivy Leaguer. He's rolling in dough. Easy for him to pooh-pooh the status quo.

But, it turns out, his anti-college ideas stem from personal experience. After his first year at Cornell University, Altucher says his parents lost money and couldn't afford tuition. So he paid his own way, working 60 hours a week delivering pizza and tutoring, on top of his course load.

He left Cornell thousands of dollars in debt. He also left with a degree in computer science. But it took failing at several investment schemes, losing large sums of money and then studying the stock market on his own -- analyzing Warren Buffett's decisions so closely he ended up writing a book about him -- for Altucher to learn enough about the financial world to survive in it. He thinks he would have been better off getting the real-world lessons earlier, rather than thrashing himself to pay for school and shouldering so much debt.

It's cold comfort, but the loans put him in good company: Hundreds of billions of dollars of national student-loan debt has now overtaken American credit-card debt, the Wall Street Journal recently reported, using numbers compiled by FinAid.org, a Web site for college financial aid information.

"There's a billion other things you could do with your money," Altucher says. One option: Invest the money you'd spend on tuition in Treasury bills for your child's retirement. According to Altucher, $200,000 earning 5 percent a year over 50 years would amount to $2.8 million.

Few families have that kind of money lying around. But if you can give your child $10,000 or so to start his own business, Altucher says, your child will reap practical lessons never taught in a classroom. Later, when he's more mature and focused, college might be more meaningful.

* * *

The hefty price tag of a college degree has some experts worried that its benefits are fading.

"I think it makes less sense for more families than it did five years ago," says Richard Vedder, an economics professor at Ohio University who has been studying education issues. "It's become more and more problematic about whether people should be going to college."

That applies not just to astronomically priced private schools but to state schools as well, where tuitions have spiked. Student loans can postpone the pain of paying, but they come due when many young adults are at their most financially vulnerable, and default rates are high. Even community colleges, while helping some to keep costs down, prompt many to take out loans -- which can land them in severe credit trouble.

According to a report in the Chronicle of Higher Education, 31 percent of loans made to community college students are in default. (The same report found that 25 percent of all government student loans default.) Default on a student loan and face dire consequences, beyond a bad credit record -- which can tarnish hopes of getting a car, an apartment or even a job: Uncle Sam can claim your tax refunds and wages.

Now, take a key argument in favor of getting a four-year degree, the one that says on average, those with one earn more than those without it. Education Department numbers support this: In 2008, the median annual earnings of young adults with bachelor's degrees was $46,000; it was $30,000 for those with high school diplomas or equivalencies. This means that, for those with a bachelor's degree, the middle range of earnings was about 53 percent more than for those holding only a high school diploma.

But a lot of college graduates fall outside the middle range -- and many stand to make considerably less.

"If you major in accounting or engineering, you're pretty likely to get a return on your investment," Vedder says. "If you're majoring in anthropology or social work or education, the rate on return is going to be a good deal lower, on average.

"I've talked to some of my own students who've graduated and who are working in grocery stores or Wal-Mart," he says. "The fellow who cut my tree down had a master's degree and was an honors grad."

The unemployment rate among those with bachelor's degrees is at an all-time high. In 1970, when the overall unemployment rate was 4.9 percent, unemployment among college graduates was negligible, at 1.2 percent, Vedder says, citing figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But this year, with the national rate of unemployment at 9.6 percent, unemployment for college graduates has risen to 4.9 percent -- more than half the rate of the general population. The bonus for those with degrees is "less pronounced than it used to be," Vedder says.

"The return on investment is clearly lower today than it was five years ago," he says. "The gains for going to college have leveled off."

Before hackles are raised about boiling the salutary effects of higher education down to its cost, there are obvious disclaimers: Education is a priceless thing. Many high-school graduates are not ready for independence and adult responsibilities, and college provides a safe place for them to grow up -- for a fee.

But what about the lessons offered by the success stories that have unspooled along a different path? Dropouts are the toast of the dot-com world. To the non-degreed billionaires' club headed by Microsoft's Bill Gates (Harvard's most famous quitter) and Apple's Steve Jobs (left Oregon's Reed College after a single semester), add: Michael Dell (founder of Dell Computers, University of Texas dropout), Microsoft co-founder and Seattle Seahawks owner Paul Allen (quit Washington State University) and Larry Ellison (founder of Oracle Systems, gave up on the University of Illinois).

Success sans sheepskin isn't only for the technology set.

David Geffen, co-founder of DreamWorks, bowed out of several schools, including the University of Texas.

Redskins owner Daniel Snyder dropped out of the University of Maryland.

Barry Gossett, chief executive of Baltimore's Acton Mobile Industries, builders of temporary trailers, also left Maryland without a degree. (No hard feelings, apparently: In 2007, he donated $10 million to the school.)

Perhaps these are unique individuals in whom a driving entrepreneurial spirit outstripped the plodding pace of book learning.

Or perhaps they point to a new model.

"There's nothing you can't do on your own," Altucher says. A provocative idea -- and a liberating one. Even if it's not entirely true.

But you don't have to agree with Altucher to concede that the debt-stress many graduates or their parents -- or both -- are left with after tossing off the cap and gown works against the merits of the degree.

Even if a kid doesn't party his way through college, chances are he or his family has plowed a boatload of money into a few memorable classes and a lot of boredom.

On top of that, you don't know how big a boatload it'll be. For many college students, four years of anticipated tuition payments grows to five years or six -- or more. Government statistics show just 57 percent of full-time college students get their bachelor's degrees in six or fewer years.

And the rest . . . don't.

* * *

In her youth, Toni Reinhart, 55, owner of Comfort Keepers Reston, a licensed home-care agency in Northern Virginia, abandoned hopes of completing a business degree at George Mason University. There was that C in accounting, and then trigonometry. . . .

"My problem was not being able to put the time in to learn things I wasn't interested in," she says.

Has dropping out held her back?

"Oh sure," says Reinhart, a self-described late-bloomer. "But maybe that's good. Maybe it held me back from things I shouldn't have been doing anyway."

Now she manages 56 employees and in recent years hit the million-dollar mark in gross revenue.

"I understand the case for finishing, because you've proven you can stick with something," she says. "But wouldn't it be nice if we did have another path that didn't put people in debt for . . . $100,000? Isn't there another way to instill those kinds of lessons in people that would be cheaper?"

Nelson Cortez, 20, wishes there were. The Napa resident starts his third year this month at the University of California at Santa Cruz. He's received state grants and works 15 hours a week while school is in session, but with the loans he's taken out, he estimates he's already about $25,000 in debt. This is why, when the California Board of Regents last year announced a 32 percent increase in fees, he joined protests that galvanized students around the state -- and set off similar protests around the country.

Cortez helped shut down the Santa Cruz campus and traveled to the District to rally outside the U.S. Capitol. (On Oct. 2, students will demonstrate on the Mall for affordable education as part of the One Nation march, organized by civil rights and youth groups and unions.)

"Rent was due yesterday, and I was $20 short, and I'm running around the house looking for $20," Cortez says. His money problems have caused him to question whether he's made the right decision: "Am I going to be able to afford it, should I take a semester off? . . . I do have in the back of my mind, would it be better not to have those loans and just work?"

According to the Education Department, between 1997-98 and 2007-08, prices for undergraduate tuition, room and board at public institutions of higher education rose by 30 percent, and prices at private institutions rose by 23 percent -- after adjustments for inflation. "The reason colleges have been getting away with raising their fees so much is that loans allow parents to tough it out," Vedder says.

Federal government moves, such as tuition tax credits, allow those paying college costs to subtract a certain amount from their tax bills. But it does little to alleviate the financial burden, Vedder says, adding that it gives colleges an excuse to raise costs further.

* * *

The cost of college is putting the financial screws to an entire generation, say student activists.

"I think it's absolutely despicable that students are asked to pay that much," says Lindsay McCluskey, president of the United States Student Association. "In terms of public education, you can't even call that public when students are taking out an average of $25,000 to complete college and then are paying off student loan debt until they're 50 or 60 years old."

A recent graduate of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where she majored in anthropology, McCluskey is paying down a $20,000 student loan. She thinks it will probably take her a decade to dig out of that hole -- while the balance is accumulating interest -- because she can't afford to make more than the minimum monthly payments.

"For my generation," McCluskey, 23, says, "that loan debt is taking the place of the house we could be buying or a number of other investments we could be making in our lives. The loan debt just sucks a lot of that out."

Now consider Jeremiah Stone, 25. The graduate of Rockville's Thomas S. Wootton High School is living in Paris, pursuing a drool-worthy international career as a chef. After high school, he took a job as a barback in a Houston's Restaurant, worked up to kitchen assistant, took a nine-month cooking course at the French Culinary Institute in New York and finally landed in France, where he has freelanced as a chef throughout the country. Eventually he hopes to open his own restaurant in New York.

"People I meet for the first time, they're always saying, 'Oh, if I had another career, I'd be a pastry chef instead of becoming a lawyer,' " Stone says. In the eyes of some of his friends, he says, he's become emblematic of simply doing what you love. In his case, it turns out that not following the herd was the best investment of all.

Source: Washington Post / Sarah Kaufman.

Link: Bypassing a higher education

Illustration: Tim Lahan.

Moderator: ART HuNTER.

#propaganda#contemporary world#postmodern thinking#neoliberal capitalism#economy#washington post#tim lahan#brainslide bedrock education talk#education#knowledge#article#free your mind

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Education: Our Most Overrated Product (Psychology Today)

It’s almost embarrassing to make these recommendations. Although I have a Ph.D. specializing in evaluation of education from Berkeley and subsequently taught in its graduate school, the changes to education I’ll suggest are just common sense.

Replace mixed-ability classes with ability-grouped classes

In most elementary and even in some high schools, we now place kids in classes at random. That makes it much more difficult for teachers to meet students’ needs than if the classes were grouped by ability and/or achievement.

If you wanted to start learning Mandarin, you’d learn a lot less if the class consisted mainly of non-beginners, but for political reasons, elementary school students are typically assigned to a classroom a random even though it means that students learn less.

To ensure that low-ability classes don’t trap students in an inappropriately low-level class, placement must be dynamic and flexible, that is, each child reviewed regularly to ensure s/he is in the best-suited group or class.

The New York Times reports a resurgence in use of flexible ability grouping. This trend deserves to be, pardon the pun, fast-tracked.

Replace one-size-fits-all high school curriculum with multiple pathways..

We insist on a one-size-fits-all curriculum: everyone to college, even though many students would benefit from another path, for example, a career-centric curriculum, including an apprenticeship. If after eight years of school, you are still reading at the 5thgrade level, it’s foolish, even sadistic, to eliminate all options for you other than four years of deciphering Shakespeare, analyzing trigonometric functions, etc.

Wouldn’t it be wiser to capitalize on your relative strengths — perhaps helping people, working with your hands, or the creative arts? Most other developed countries realize that one-size-fits-all education doesn’t fit all. For example, in Germany, over half of high school students opt for a career-preparatory rather than college-preparatory high school path. Youth unemployment in Germany is half the U.S.'s.

With over half of U.S. college graduates under 25 unemployed or doing work they could have done with just a high school diploma, college is not as clearly a wise choice as it once was.

Don’t mandate arcana until life’s basics are learned.

We insist that every high school graduate able to solve quadratic equations and understand stochastic processes, esoterica that 99.9% of us never use, yet we allow them to graduate with poor or untested skills in conflict resolution, managing money, and parenting. Don’t we all know people who, despite an advanced degree, lack such critical skills?

From kindergarten through graduate school, we should first ensure that students graduate with important basics before we get to esoterica. That means stopping the arcana-enamored professoriate from dictating our K-16 curriculum.

Replace foreign language and P.E. with subjects likely to yield greater benefit.

We mandate physical education K-12 when in fact, students learn little there and there’s little evidence it enduringly increases physical fitness. Indeed, a study by the Women’s Sport and Fitness Foundation found that required PE makes girls less likely to do exercise!

We make students take years of foreign language when it’s well known that it’s extremely difficult for most students to learn a language past the age of five unless living in a country that speaks only that language.

STEM is oversold.

We’re doing an full-court press to get more students to major in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), claiming that’s where the jobs will be. We’d need to be awfully sure of that because most people find those majors extremely difficult and not particularly interesting. And by the time most of those students have finished their STEM degrees, even more STEM jobs will be offshored or automated.

Already, we have many more STEM graduates than there are jobs, even at the Ph.D. level. I gave a workshop on finding work for young neuroscience Ph.D.s. It drew 450 attendees. Afterwards, over 100 of them waited in line to talk with me – nearly all unemployed.

Stop tenure.

Because time takes its toll on people, we don’t give lifetime job security, for example, to social workers, lawyers, or doctors. You can be good in the beginning but burned out later. Yet after just two or three years, we give teachers lifetime tenure despite being aware of teachers who continue to bore and/or be punitive to class after class of students until they finally retire when they’ve maximized their pension. What could be more foolish and destructive to children and their learning?

Replace live teachers or at least homework with dream-team-taught online lessons.

We’ve let the teacher’s unions strangle education in an even more important way. The unions insist that a course be taught by a live teacher rather than an online course taught by a dream team of the world’s most transformational instructors using simulations, video, interactivity, and ongoing assessment and individualized branching. A live teacher or paraprofessional would supplement to provide the human touch.

Dream-team-taught courses or homework would enable every child, rich and poor, from Maine to California, to have world-class instruction, even in subjects with a shortage of transformational teachers, for example, math, physics, and computer science. But that would doubtless eliminate teaching positions and the unions would rather save those even if children are more poorly educated.

Replace professors with transformative instructors.

Most college instructors are Ph.D.s, people who deliberately opted out of the real world to get an research degree, whose interests and abilities are usually greater in their arcane research than in teaching undergraduates. There just is too great a gap in intellectual ability, interests, and learning style between most Ph.D.s and their typical undergraduate students.

The best undergraduate instructors may hold only a bachelor's degree but have the ability to explain, motivate, and generate important learning. Professors are never held accountable for how much their students learn. And indeed studies of freshman-to-senior growth show that almost half of students grow little or not at all in writing, critical thinking, and analytical reasoning, perhaps the most important things one should derive from a college education.

Ensure ideological diversity.

Much wisdom resides left of center, but not all. Schools and colleges should be a marketplace of ideas, representing the full range of benevolently derived, intelligent thought from far left to far right. Unfortunately, acceleratingly, teachers and especially university faculty present and advocate mainly left-of-center ideas. The hiring, training, and promoting of instructors should reflect teachers' near-sacred obligation to fairly and competently present a range of perspectives.

Replace country-club campuses with cost-effective ones.

Sticker price for an undergraduate degree at a brand-name private college is a quarter of a million dollars, assuming you graduate in four years. And nationwide, 41 percent don’t graduate even if given six years!

Financial aid? For most, the bulk is loan, which must be paid back with interest. And the higher education lobby is so powerful that it convinced Congress to make students loans virtually the only loan that cannot be discharged in bankruptcy. So even though 53 percentof college graduates under 25 are unemployed or doing work they could have done with just a high school diploma, those students are stuck, absolutely stuck, with that massive debt.

In addition to porcine administrations, a major reason for higher education's obscene cost is the country-club-like campus, replete with fabulous libraries, when most people do their reading and research on the Net and e-reader. Campuses should be much smaller and more spartan and thus more cost-effective.

America’s most overrated product.

Education is viewed as a magic pill, our nation’s most valuable product. In my view, it is America’s most overrated. For education to have a chance to fulfill its promise, we need to strengthen our resolve to force education to change:

Stop letting the teachers unions strangle educational quality. Stop letting the outré-obsessed professoriate dictate curriculum in graduate school, college, let alone K-12 curriculum. We require tires to provide more visible consumer information than we require of colleges. We should require colleges to, on their home page, post their amount of student growth in learning and employability instead of photos of enraptured students and happy (if unemployed) graduates in cap and gown.

Only then can education possibly hope to close the achievement gap as well as enable our bright students to live up to their potential and enjoy school. Yes, enjoy. It’s a word too excised from the education experience.

Source: Psychology Today / Marty Nemko Ph. D.

Link: Education: Our Most Overrated Product

Illustration: Otto Rapp - "Pablos Last Concert".

Moderator: ART HuNTER.

#propaganda#contemporary world#postmodern thinking#neoliberal capitalism#education#psychology today#otto rapp#economy#article#knowledge#brainslide bedrock education talk#free your mind

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lifelong learning is becoming an economic imperative

THE RECEPTION AREA contains a segment of a decommissioned Underground train carriage, where visitors wait to be collected. The surfaces are wood and glass. In each room the talk is of code, web development and data science. At first sight the London office of General Assembly looks like that of any other tech startup. But there is one big difference: whereas most firms use technology to sell their products online, General Assembly uses the physical world to teach technology. Its office is also a campus. The rooms are full of students learning and practising code, many of whom have quit their jobs to come here. Full-time participants have paid between £8,000 and £10,000 ($9,900-12,400) to learn the lingua franca of the digital economy in a programme lasting 10-12 weeks.

General Assembly, with campuses in 20 cities from Seattle to Sydney, has an alumni body of around 35,000 graduates. Most of those who enroll for full-time courses expect them to lead to new careers. The company’s curriculum is based on conversations with employers about the skills they are critically short of. It holds “meet and hire” events where firms can see the coding work done by its students. Career advisers help students with their presentation and interview techniques. General Assembly measures its success by how many of its graduates get a paid, permanent, full-time job in their desired field. Of its 2014-15 crop, three-quarters used the firm’s career-advisory services, and 99% of those were hired within 180 days of beginning their job hunt.

The company’s founder, Jake Schwartz, was inspired to start the company by two personal experiences: a spell of drifting after he realised that his degree from Yale conferred no practical skills, and a two-year MBA that he felt had cost too much time and money: “I wanted to change the return-on-investment equation in education by bringing down the costs and providing the skills that employers were desperate for.”

In rich countries the link between learning and earning has tended to follow a simple rule: get as much formal education as you can early in life, and reap corresponding rewards for the rest of your career. The literature suggests that each additional year of schooling is associated with an 8-13% rise in hourly earnings. In the period since the financial crisis, the costs of leaving school early have become even clearer. In America, the unemployment rate steadily drops as you go up the educational ladder.

Many believe that technological change only strengthens the case for more formal education. Jobs made up of routine tasks that are easy to automate or offshore have been in decline. The usual flipside of that observation is that the number of jobs requiring greater cognitive skill has been growing. The labour market is forking, and those with college degrees will naturally shift into the lane that leads to higher-paying jobs.

The reality seems to be more complex. The returns to education, even for the high-skilled, have become less clear-cut. Between 1982 and 2001 the average wages earned by American workers with a bachelor’s degree rose by 31%, whereas those of high-school graduates did not budge, according to the New York Federal Reserve. But in the following 12 years the wages of college graduates fell by more than those of their less educated peers. Meanwhile, tuition costs at universities have been rising.

A question of degree, and then some

The decision to go to college still makes sense for most, but the idea of a mechanistic relationship between education and wages has taken a knock. A recent survey conducted by the Pew Research Centre showed that a mere 16% of Americans think that a four-year degree course prepares students very well for a high-paying job in the modern economy. Some of this may be a cyclical effect of the financial crisis and its economic aftermath. Some of it may be simply a matter of supply: as more people hold college degrees, the associated premium goes down. But technology also seems to be complicating the picture.

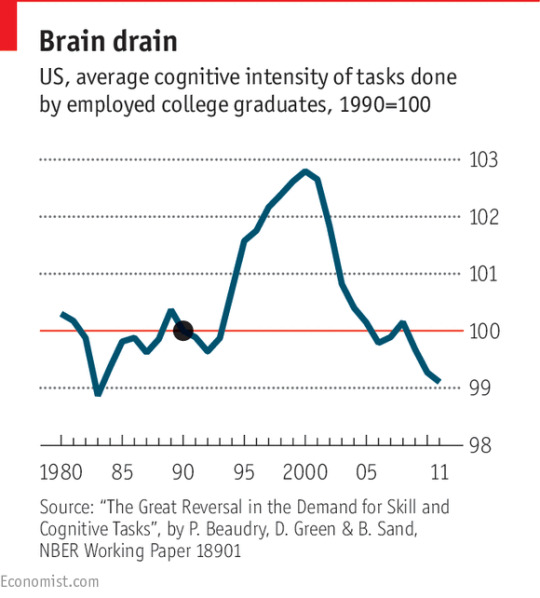

A paper published in 2013 by a trio of Canadian economists, Paul Beaudry, David Green and Benjamin Sand, questions optimistic assumptions about demand for non-routine work. In the two decades prior to 2000, demand for cognitive skills soared as the basic infrastructure of the IT age (computers, servers, base stations and fibre-optic cables) was being built; now that the technology is largely in place, this demand has waned, say the authors. They show that since 2000 the share of employment accounted for by high-skilled jobs in America has been falling. As a result, college-educated workers are taking on jobs that are cognitively less demanding (see chart), displacing less educated workers.

This analysis buttresses the view that technology is already playing havoc with employment. Skilled and unskilled workers alike are in trouble. Those with a better education are still more likely to find work, but there is now a fair chance that it will be unenjoyable. Those who never made it to college face being squeezed out of the workforce altogether. This is the argument of the techno-pessimists, exemplified by the projections of Carl-Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne, of Oxford University, who in 2013 famously calculated that 47% of existing jobs in America are susceptible to automation.

There is another, less apocalyptic possibility. James Bessen, an economist at Boston University, has worked out the effects of automation on specific professions and finds that since 1980 employment has been growing faster in occupations that use computers than in those that do not. That is because automation tends to affect tasks within an occupation rather than wiping out jobs in their entirety. Partial automation can actually increase demand by reducing costs: despite the introduction of the barcode scanner in supermarkets and the ATM in banks, for example, the number of cashiers and bank tellers has grown.

But even though technology may not destroy jobs in aggregate, it does force change upon many people. Between 1996 and 2015 the share of the American workforce employed in routine office jobs declined from 25.5% to 21%, eliminating 7m jobs. According to research by Pascual Restrepo of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the 2007-08 financial crisis made things worse: between 2007 and 2015 job openings for unskilled routine work suffered a 55% decline relative to other jobs.

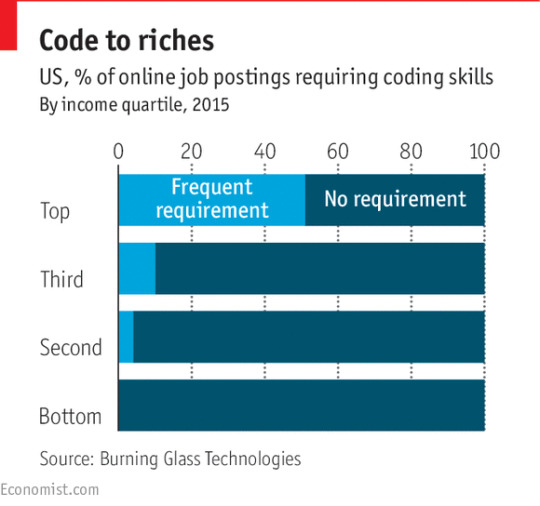

In many occupations it has become essential to acquire new skills as established ones become obsolete. Burning Glass Technologies, a Boston-based startup that analyses labour markets by scraping data from online job advertisements, finds that the biggest demand is for new combinations of skills—what its boss, Matt Sigelman, calls “hybrid jobs”. Coding skills, for example, are now being required well beyond the technology sector. In America, 49% of postings in the quartile of occupations with the highest pay are for jobs that frequently ask for coding skills (see chart). The composition of new jobs is also changing rapidly. Over the past five years, demand for data analysts has grown by 372%; within that segment, demand for data-visualisation skills has shot up by 2,574%.

A college degree at the start of a working career does not answer the need for the continuous acquisition of new skills, especially as career spans are lengthening. Vocational training is good at giving people job-specific skills, but those, too, will need to be updated over and over again during a career lasting decades. “Germany is often lauded for its apprenticeships, but the economy has failed to adapt to the knowledge economy,” says Andreas Schleicher, head of the education directorate of the OECD, a club of mostly rich countries. “Vocational training has a role, but training someone early to do one thing all their lives is not the answer to lifelong learning.”

Such specific expertise is meant to be acquired on the job, but employers seem to have become less willing to invest in training their workforces. In its 2015 Economic Report of the President, America’s Council of Economic Advisers found that the share of the country’s workers receiving either paid-for or on-the-job training had fallen steadily between 1996 and 2008. In Britain the average amount of training received by workers almost halved between 1997 and 2009, to just 0.69 hours a week.

Perhaps employers themselves are not sure what kind of expertise they need. But it could also be that training budgets are particularly vulnerable to cuts when the pressure is on. Changes in labour-market patterns may play a part too: companies now have a broader range of options for getting the job done, from automation and offshoring to using self-employed workers and crowdsourcing. “Organisations have moved from creating talent to consuming work,” says Jonas Prising, the boss of Manpower, an employment consultancy.

Add all of this up, and it becomes clear that times have got tougher for workers of all kinds. A college degree is still a prerequisite for many jobs, but employers often do not trust it enough to hire workers just on the strength of that, without experience. In many occupations workers on company payrolls face the prospect that their existing skills will become obsolete, yet it is often not obvious how they can gain new ones. “It is now reasonable to ask a marketing professional to be able to develop algorithms,” says Mr Sigelman, “but a linear career in marketing doesn’t offer an opportunity to acquire those skills.” And a growing number of people are self-employed. In America the share of temporary workers, contractors and freelancers in the workforce rose from 10.1% in 2005 to 15.8% in 2015.

Reboot camp

The answer seems obvious. To remain competitive, and to give low- and high-skilled workers alike the best chance of success, economies need to offer training and career-focused education throughout people’s working lives. This special report will chart some of the efforts being made to connect education and employment in new ways, both by smoothing entry into the labour force and by enabling people to learn new skills throughout their careers. Many of these initiatives are still embryonic, but they offer a glimpse into the future and a guide to the problems raised by lifelong reskilling.

Quite a lot is already happening on the ground. General Assembly, for example, is just one of a number of coding-bootcamp providers. Massive open online courses (MOOCs) offered by companies such as Coursera and Udacity, feted at the start of this decade and then dismissed as hype within a couple of years, have embraced new employment-focused business models. LinkedIn, a professional-networking site, bought an online training business, Lynda, in 2015 and is now offering courses through a service called LinkedIn Learning. Pluralsight has a library of on-demand training videos and a valuation in unicorn territory. Amazon’s cloud-computing division also has an education arm.

Universities are embracing online and modular learning more vigorously. Places like Singapore are investing heavily in providing their citizens with learning credits that they can draw on throughout their working lives. Individuals, too, increasingly seem to accept the need for continuous rebooting. According to the Pew survey, 54% of all working Americans think it will be essential to develop new skills throughout their working lives; among adults under 30 the number goes up to 61%. Another survey, conducted by Manpower in 2016, found that 93% of millennials were willing to spend their own money on further training. Meanwhile, employers are putting increasing emphasis on learning as a skill in its own right.

Source: The Economist / Special report.

Link: Lifelong learning is becoming an economic imperative

Illustration: Paul Rumsey.

Moderator: ART HuNTER.

#propaganda#neoliberal capitalism#postmodern thinking#contemporary world#economy#education#knowledge#brainslide bedrock education talk#paul rumsey#the economist#technology#free your mind

0 notes

Text

Although 7.1M Students are Taking Online Courses, Educators Give the Trend Low Marks

After a swift surge, online enrollment growth has slightly slipped. Emphasis on the "slightly," however, because the popularity is still apparent, with more than 7.1 million students taking at least one online course, according to a study released Wednesday by the Babson Survey Research Group.

The 6.1 percent growth rate represents the lowest in a decade. The dip is one reflected in the faculty. The percentage of chief academic leaders claiming online learning is critical to their long-term strategy dropped from 69.1 to 65.9 this year. The pool of academic leaders who rated online education's learning outcomes as the same or superior to the outcomes produced from face-to-face interaction also fell from 77 to 74.1 percent.

Jeff Seaman, co-director of the Babson Survey Research Group, assured in a statement, "Institutions with online offerings remain as positive as ever about online learning." Yet, he did add, "There has been a retreat among leaders at institutions that do not have any online offerings."

A mere five percent of higher education institutions currently offer a massive open online course, while another 9.3 percent report MOOCs are in the planning stages. Locally renowned is online learning nonprofit edX, jointly founded by Harvard and MIT. Thirty institutions, home and abroad, are now utilizing the platform to deliver free online courses.

Unfortunately, the study found that less than 25 percent of academic leaders find MOOCs a sustainable method for offering online courses. Todd Hitchcock, senior vice president of Pearson Online Learning Services, suggested a shift in attitude, however, arguing that "the need to provide relevant educational opportunities that will help students meet their career goals" is core to growing the country's economy.

Pearson provided financial support for the report alongside The Sloan Consortium. Both have deemed online learning of the utmost importance, and are encouraging more institutions to jump on board.

As former MIT President Susan Hockfield said when edX launched in May 2012:

"Today, in higher education, generally, you can choose to view this era as one of threatening change and unsettling volatility, or you can see it as a moment charged with the most exciting possibilities presented to educators in our lifetimes. [...] Online education is not an enemy of residential education, but rather a profoundly liberating and inspiring ally."

More than 7.1 million people appear to agree.

Source: BostInno / Lauren Landry.

Link: 7.1M Students are Taking Online Courses

Illustration: Ryan Thornburg.

Moderator: ART HuNTER.

#propaganda#postmodern thinking#contemporary world#neoliberal capitalism#economy#education#knowledge#technology#portfolio#bostinno#ryan thornburg#brainslide bedrock education talk#free your mind

0 notes