#catiline his conspiracy

Text

A serpent, ere he comes to be a dragon,

does eat a bat; and so must you - a consul.

As a consul, this bat is wearing a praetexta.

[I do not know the authorship of the model, as the YouTube video I got it from neglected to mention it. If you know who the author is, please let me know so I could credit them.]

[The quote is from Ben Jonson's Catiline his conspiracy, in which Caesar is persuading Catiline to stop picking at his food and eat Cicero.]

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE GREATEST CONSPIRACY PLAY EVER MADE

BEN JONSON PRESENTS

CATILINE HIS CONSPIRACY

A KING'S MEN PRODUCTION

A PLAY BY SALLUSTIO GCBC0691

ABOUT THE CATILINARIAN CONSPIRACY

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crassus, Caelius, Cicero, Catiline, Conspiracy

boy howdy these four sure are something. not featured in this soup of C names, Caesar! what on earth happened here.

Plutarch, Crassus

Sallust on Crassus, Ronald Syme

Patron and Client, Father and Son in Cicero's "Pro Caelio"

Crassus' New Friends and Pompey's Return, Eve J. Parrish

Catullus and His World, T.P. Wiseman

Cicero's Catilinarians, D.H. Berry

#flash back to several years ago when I said I could never retain info on Catiline. Turns out the missing link was Crassus lmao#about halfway through drawing this i realized hbo rome era james purefoy would make a really good catiline#which is. not a good thought. bc when i start figuring out casts is when i start thinking thoughts like 'oh what if i did a comic'#conspiracy spotted. absolutely no survivors found here. good grief. we got whatever is going on with caelius. also some kind of divorce#but actually. hey cicero. HEY CICERO. I HAVE SOME QUESTIONS. FOR YOU ACTUALLY---#i remember kaine told me about the executions but i did not fully appreciate. exactly what any of it meant in context. i have context now!#i should've been drawing the man with fucked up wall shadows the entire time. my god.#drawing tag#roman republic tag#catiline#Lucius Sergius Catilina#have i never. tagged him by his full name here. i should draw him more#cicero#marcus tullius cicero#marcus licinius crassus#marcus caelius rufus

327 notes

·

View notes

Text

HAPPY CAESAR-FELL-DOWN-IN-FRONT-OF-EVERYONE-AND-TRIED-TO-PLAY-IT-OFF DAY!

#all those bad omens just for the thapsus elephants to fuck the pompeians over#definitely top 3 caesar moments for me though#number two being him giving Cato the love letter from his sister during the catiline conspiracy#and number one being ‘that is if pontius Aquila will allow me’

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: two excerpts from sallust’s “the jugurthine war”. the first reads, “in this massacre, perpetrated by a savage enemy in a completely closed city, the commandant turpilius was the only italian who got away unhurt. whether he owed his escape to his host’s compassion, or to a secret bargain, or simply to luck, i have not discovered. in any case, a man who in such a calamity could prefer dishonourable survival to an untarnished name must have been a detestable wretch.” the second reads, “turpilius, who, it will be remembered, had been the only man to escape, was put on trial by metellus, and as he could offer no satisfactory defence, he was convicted. his punishment was flogging and execution - for he possessed the rights only of a ‘latin’ citizen.” /end ID.]

captivated by this guy who was executed for the heinous crime of surviving a massacre

#rome moment#jugurthine war#man i really like sallust i wish he had more extant works#though im soooo glad one of his surviving works is the conspiracy of catiline#sorry for highlighting my book My bad. however i did Purchase it with mine own Money.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

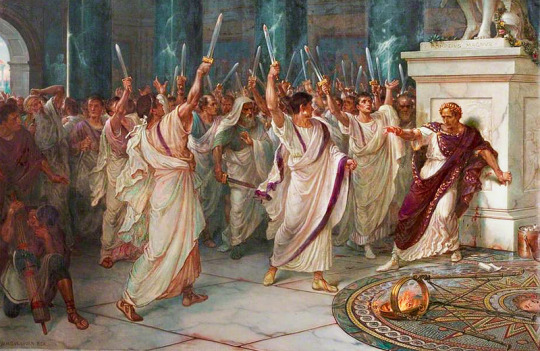

Cicero & the Catiline Conspiracy

The Roman Republic was in death's throes. Within a few short years, the “dictator for life” Julius Caesar would be assassinated, and, as a result, the government would descend into chaos. The consequence of a long civil war would bring the birth of an empire under the watchful eye of an emperor; however, it would also witness the loss of many personal liberties - liberties that were the pride of the people and the result of a long history of struggle and strife. Nevertheless, that was in the future - the year is 63 BCE and the city of Rome and the foundation of the Republic is being threatened. Luckily, one man would rise amidst the disorder, at least in his mind, to save it.

Rome's Economic Crisis

The year 63 BCE saw Rome as a city of almost one million residents, governing an empire that ranged from Hispania in the west to Syria in Middle East and from Gaul in the north to the deserts of Africa. Outside the eternal city, in the provinces, the next few decades would bring a strengthening of the borders - Pompey battling King Mithridates of Pontus in the East while Julius Caesar fought the assorted tribes of Gaul and Germany to the north, but at home Rome was facing an internal threat. The difficulties on the home front stemmed from troubles developing in the eastern provinces.

A significant decrease in trade and the resulting loss of tax revenue resulted in an increase in debt among many of the more affluent Romans. Unemployment in the city was high. The Roman Senate stood silent, unable or unwilling to come to a solution. The people longed for a hero, namely the ever-popular Pompey, to return and bring a remedy. In the meantime, however, there was serious - or so it appeared - unrest, an unrest that led to a conspiracy, a supposed conspiracy that threatened not only the lives of the people who lived within the walls of Rome but also the city itself.

Continue reading...

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Top 5 favorite historical events 👀

Oo, good one! Thanks for the ask ✨

1. The Ides of March

Apart from being a beloved Tumblr holiday, I just find the whole event so interesting! Few times in history have had such a lasting cultural impact (hello, statue of Brutus at the National Convention!).

Plus it's so wonderfully morally grey, which you can see from the different perception of Brutus throughout history (burning in lowest circle of Dante's hell vs. being hailed as a hero by the French revolutionaries).

Was it the right thing to do? It was an act of extreme violence, and the republic was arguably beyond saving anyway, as became clear later. Does it mean it was the wrong thing to do though? I'm definitely not qualified to answer that. But it is an interesting question to think about, which makes this event one of my favourites.

(Plus the whole thing kind of reads like an ancient tragedy, since it could be read as Brutus (& co) killing someone who was essentially a father figure to him, but also was widely known to have slept with his mother. Hamlet who?)

2. Camille rallying the crowds at Palais Royal

I'm a sucker for a good epic moment, and this is certainly one of them. Camille leaping on the table and overcoming his stutter to address the crowd of dissatisfied Parisians, inspiring them to take action? Yes please!

(not to mention that any event that demonstrates the power that words can have is going to be automatically interesting in my book.)

3. The Servilia Letter Affair

Situated during the late Roman Republic after the Catiline conspiracy, it's another hilarious evidence of the fact that poor Cato the Younger simply couldn't catch a break.

For those uninitiated: as Cato and Caesar were arguing about what kind of punishment is appropriate for the conspirators wanting to overthrow the consul, a mysterious letter was delivered to Caesar, right in the senate.

Cato suspected that there was something foul going on, something that could potentially link Caesar - Cato's oponent - to the conspiracy that was just being discussed. He therefore seized the letter from Caesar and insisted he will read its contents out loud, in front of everyone. Doesn't sound all that unreasonable, right?

...except the document in question just happened to be a steamy, in Plutarch's words "unchaste" love-letter to Caesar, written by none other than Cato's own half-sister, Servilia.* Yikes.

Cato apparently proceeded to then throw the letter back to Caesar, saying: "Take it, thou sot." Iconic.

* who was also Brutus' mother. See, it's all connected!

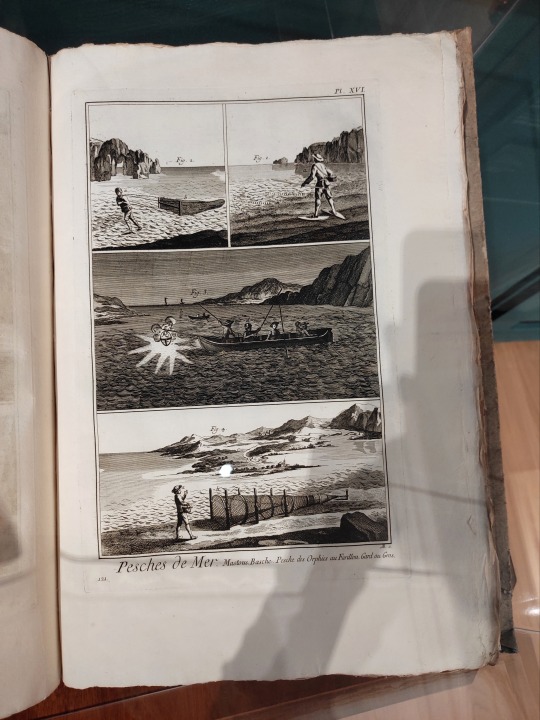

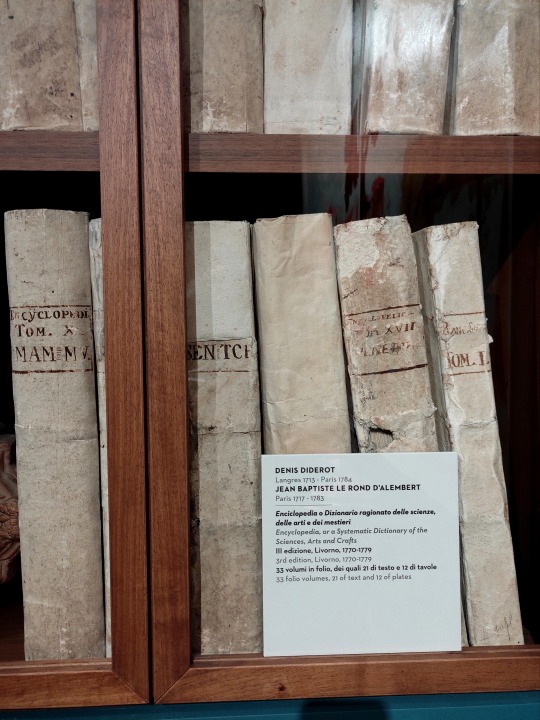

4. Publishing of the Éncyclopedie

I just love studying the Age of Enlightenment as a whole, but I think the Éncyclopedie is perhaps the best embodiment of all of the things the era was about. I like learning about the Éncyclopedistes - their petty personal dramas are fun to read about, but I also like the fact that what fuelled the project was a (mostly) genuine desire to educate people and make human knowledge more readily available to the masses.

Also look what I came across while in Verona!! ->

5. Women's March on Versailles

A great reminder that women can be a strong political force and that their place in history should not be overlooked! Though it was not necessarily a women-only event, it clearly shows just how much of a significant role women (and working class people in general) played in the French Revolution.

#thanks for the ask!#ask game#history#sorry for taking ages#french revolution#frev#frevblr#camille desmoulins#women's march on versailles#1700s#18th century#roman republic#tagamemnon#marcus junius brutus#brutus#ides of march#julius caesar#ancient rome#cato the younger#servilia#encyclopedia#denis diderot#jean d'alembert#french history#age of enlightenment

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

what are your most favorite caesar facts :-) (<- for brain distraction)

POV you asked an overexcited little boy to show you his favorite hot wheels

Despite the common English pronunciation, Caesar would have said his name something like "kai-oos you-lee-us kay-zhar". This pronunciation is the origin of the king's titles kaiser (German/Prussian) and czar/tsar (Russian)

On that note, his famous quote "veni, vidi, vici" would have been said "whey-nee wee-dee whee-key" which is less cool for gym bros to get tattooed. And while he probably didn't have any "last words" besides an exclamation of initial shock, the other most likely is the Greek "kai su teknon", meaning "you too, child", directed at Brutus. This is often assumed to be an expression of hurt and betrayal, but the wording is actually the same as known curse tablets and was probably more along the lines of a snide "and the same to you, boy"

He shaved his dick and balls and it made Cicero really mad

Had his co-consul thrown in animal manure in front of a crowd he'd gathered to watch. Later he had the guy jumped which scared him so much that he didn't leave his house for the rest of their term. This led to the common saying at the time that Rome was "under the consulship of Julius and Caesar"

His number one political rival Cato accused him of being part of a conspiracy when he got a letter covertly delivered to him in a senate meeting, but it was read aloud and was actually an ancient sext from Brutus' mom

He was probably part of the conspiracy too tbh but no one can for sure prove it

Helped his friend Clodius (noted crossdresser for pussy) get adopted by a guy younger than him to run a political scam

People called him the Queen of Bithynia because everyone liked to say he fucked Mithridates II of Bosporus, and he was often called "every woman's man and every man's woman". The poet Catiline also wrote a little ditty about how Caesar is a flaming gay who takes it up the ass

Not really a fun fact, but Caesar managed to kill off 1/3 of the Gallic population (about a million people) in eight years, putting him only a couple spots below the top ten most prolific killers in history

Caesar did not conquer Britain. They kicked his ass all the way back to Rome

Despite his reputation as the first emperor, Caesar never held the title of princeps. The first emperor was his adopted son and successor, Augustus. The only non-standard military titles he ever held were consul and dictator (not the current meaning of the term).

If you're interested in knowing what Caesar looked like, the Tusculum Portrait is the only image of him that can be confidently dated to his lifetime and was probably sculpted from life as well. Don't believe the later George Clooney looking busts

#men on tiktok don't even come close to thinking about the roman empire as much as i go#rookie numbers#answered#flora.txt

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

CaesarFacts for the Ides of March

The Julii family claimed to trace their origins to a son of Aeneas after the fall of Troy, making them direct descendants of the goddess Aphrodite/Venus.

Caesar grew up and kept his main residence all his life in the Suburra, the poorest neighborhood of Rome, famous for its sex workers, immigrants, gang violence, theft, and crime.

As a youth, Caesar ran with a fashionable counter-culture group. They wore their togas "loosely belted in a feminine fashion, with fringe trailing on the ground". Basically, Roman punks in torn jean jackets and safety pins.

During the notoriously bloody dictatorship of Sulla, Caesar chose to marry Cornelia, the daughter of Sulla's enemy, Cinna. Caesar was only saved by the intervention of his mother's family and the Vestals.

Not wanting to be in Rome, he took a diplomatic post in Bithynia. A short post turned into a long one, as he became... very close... to King Nicomedes and moved into the palace. Caesar was called the "Queen of Bithynia" there and in Rome. Later, King Nicomedes willed Bythinia to Rome, care of Caesar, as Good Friends(tm) do.

On his way back to Rome, he was captured by pirates and held for ransom. Caesar was insulted that they only asked 20 talents of silver for him and demanded that his ransom be set to 50.

On the way to being exchanged, he was obnoxiously relaxed and friendly with the pirates, writing poetry at them and joking about how he was going to raise a navy and crucify them all. Upon being released, he did indeed raise a navy and crucify them all.

Despite being a patrician, Caesar was not super wealthy early in life. He funded his early political career by borrowing extreme amounts of money. Cleverly, this made his lenders realize that the only way he could pay them back was to have a successful career and win elections, forcing them to back him beyond the loans.

Cornelia died young, and Caesar married Pompeia, the granddaughter of Sulla, the dictator who wanted him dead. They kept it close in Rome.

Caesar divorced Pompeia after the Bona Dea scandal, in which the senator Clodius Pulcher crossdressed to sneak into a sacred, women-only holy ritual being hosted by Pompeia.

Caesar was quite possibly a slutty, slutty bisexual horndog. The gossip called him "every woman's husband and every man's wife". This just makes me want to high-five him though.

In the aftermath of the Catiline Conspiracy, Cato the Younger was arguing to the Senate that Caesar should be tried, since he was friendly with several conspirators. A message arrived for Caesar and Cato demanded it be read aloud in case relevant. It was from Cato's sister, thanking Caesar for their recent, vigorous lovemaking. Caesar was not tried.

Caesar was apparently an accomplished poet, though none of his works survive. His prose is excellent though, so it's not a stretch to imagine.

Besides being consul and ultimately dictator, he was also high priest of Jupiter as a youth and later Pontifex Maximus, the ultimate high priest of Rome, for the last 20 years of his life. Normally, the elected priesthoods were a complete political dead end due to a lot of restrictions on the office. Not being able to look at blood or touch weapons puts a damper on military success, for example. Caesar used his legal expertise to find loopholes to those restrictions, which let him continue his career.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

After Mr. Harrison had spoken, the question which I have before spoken of was brought forward to prevent the decision of which Mr. Hamilton, the American Cicero, arose.

Source — David Schuyler Bogart to Samuel Blachley Webb, [June 14, 1788]

It was during the state convention in Poughkeepsie that Hamilton took part in the campaign to ratify the United States Constitution in New York. He opposed conditional ratification, believing that New York would not enter the Union, while the Clinton faction, which wanted to amend the Constitution while retaining the states' secession rights, should their attempts fail.

But what I love most about this quote is the comparison to Marcus Tullius Cicero and Alexander Hamilton. Before I started studying Hamilton, I had a large interest in Roman history, especially Cicero. And it's undeniable that there are striking parallels between the two statesmen. Both Cicero and Hamilton were self-reliant figures in history, Novus homo. They were born in obscurity, under difficult means, but rose efficiently and quickly to respect through the ranks of military and civil service, resilient work, and their inception into law. Nonetheless, they were both forever burdened and never could completely suit themselves among the aristocrats of the upper-class. They even shared many characteristics; both of them were influential supporters of national constitutional power and were skilled - but also renowned to be digressive and garrulous - orators, and political philosophers. Additionally, both were incredibly stubborn, a common fault being that their refusal to yield their politics. Which would eventually lead to both their notable rise, as well as their ultimate downfall.

Hamilton often made classical references, that were even closely related to the Roman Senator. In 1794, Hamilton even wrote several essays for the American Daily Advertiser under the pseudonym, Tully. Which was an anglicized form of Marcus Tullius Cicero. [x] Additionally, he also referred to Burr as, Catiline. Which was not meant as a flattering compliment. Catiline was known for being involved in a plot to overthrow the Roman Republic. So, referring to Burr as “Catiline”, was implying that Burr was power-hungry and a threat to the new Republican US government. Hamilton wrote to Wolcott saying;

These things are to be inferred with moral certainty from the character of the man. Every step in his career proves that he has formed himself upon the model of Catiline, and he is too coldblo[o]ded and too determined a conspirator ever to change his plan.

Source — Alexander Hamilton to Oliver Wolcott Jr., [December 1800]

The two men clashed, as Catiline and Cicero were infamous rivals. Matters worsened after Cicero uncovered a conspiracy hatched by Catiline that would conduct the assassination of several elected officials and the burning of the city itself. The purpose of this attack on the city, at least as it turned out later, was to wipe out the debts of both the poor and the rich—including Catiline. Some believe the resulting disruption will force Catiline to assume the leadership role he so desperately wanted. Which parallels with Burr's failed election due to Hamilton endorsing Jefferson over him.

#Dipping a bit of my Roman history knowledge here#amrev#american history#american revolution#alexander hamiton#historical alexander hamilton#aaron burr#lucius sirgius catiline#marcus tullius cicero#roman history#history#founding fathers#cicero's history lessons

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am sure they are having a great time.

124 notes

·

View notes

Note

re: the last catiline tag. do you know if there's a place to find the ben jonson play online :0

yes! you can read it here! be warned that sometimes the text is a bit fucked (e.g. VV for W) but have fun! there are so many plays about roman history from this period and loads of them are online and they're terrible and so fun to read!!!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

SERBISYO

something from the vault! freeing this comic from my drafts; this was an older idea, just messing around with a scene earlier on in crassus' career. love a guy who. uhhh. exploits tragedy to his benefit. christ. something something the politics of opportunity.

there was originally a follow up to this about the benefits of knowing when cold hard cash is the way to go, but I realized about five minutes ago it would be a better fit to place it during the catilinarian conspiracy arc. which means I should figure out a design for catiline for real.

#roman republic tag#drawing tag#komiks tag#me??? draw catiline consistently????? absolutely not#i might have to just bite the bullet and commit to james purefoy's performance as antony as my basis for catiline#cause i got nothing. that guy is an eel in the sense that i cannot maintain a grip on him#i have decided to spare everyone the ordeal of ten million citations discussing the roman economy#partially because im very tired right now and my pdf app is freezing up#(blows a kiss) for crassus. that motherfucker. i read books on economics in my spare time now because of him

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I'm watching part 2 of a Julius Caesar documentary and most of my thoughts so far are "ok but how do you not contextualise that "the man in drag" was Clodius Pulcher? How do you not bring up that Julius Caesar traced his family line back to Aeneas, Venus and Jupiter? How do you talk about the Catiline conspiracy without bringing up Cicero? How do you talk about this period without mentioning Cicero at all??" Then I glance to the side and

I think he possessed me.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

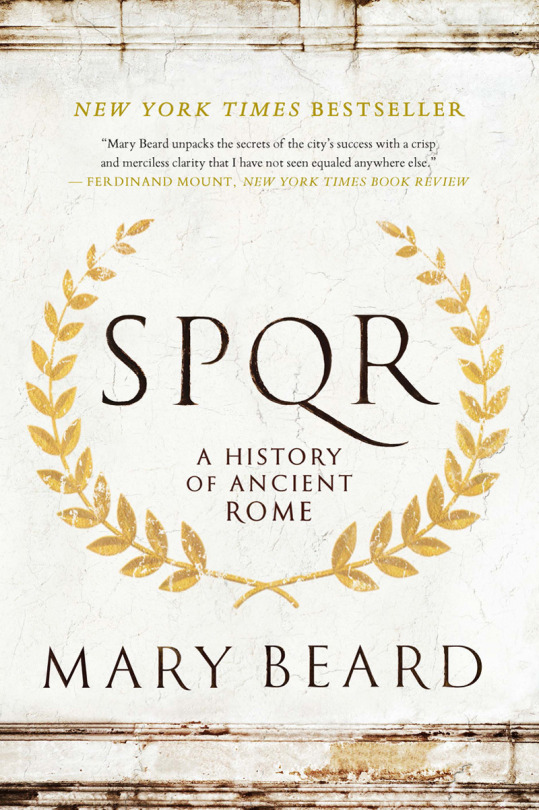

SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome by Mary Beard review – a wonderfully lucid analysis

Issues of identity and belonging preoccupied the Romans, and insistently resonate with the concerns of the early 21st century

Thanks to the sophisticated work of archaeologists, we now know more than ever about the diets, health and housing of Roman-era communities from Syria to the German frontier zone. While the lives of the vast majority remain inaccessible to us, the epitaphs of an African ex-slave who ended his days in northern Britain, or a musician from Asia who met a premature death in Rome, give tantalising glimpses of human mobility in the multicultural world of Roman imperial rule.

Yet there are individual Romans who have long been familiar. Mary Beard’s masterful study of Roman history begins with a dazzling account of one such man, Cicero, in the year he held the consulship (Rome’s most prestigious office) and the state faced a terrible political crisis, as a conspiracy led by a renegade Roman aristocrat was uncovered. Cicero’s speeches against Catiline have been a staple of classical education and a reference point for political orators. Catiline has served as a byword for subversion, but he has also been rehabilitated as a champion of the dispossessed – or at least as the symptom of a broken system rather than an incarnation of evil. Was Cicero right in ordering that Catiline and his associates be executed without trial? Beard underlines the difficulties of working out what actually happened, but she also highlights what was at stake, both in Cicero’s own time and later.

The majority of surviving accounts of early Roman history date from Cicero’s time and later, several hundred years after the city’s alleged foundation, but Beard is a wonderfully lucid guide to its murky beginnings, shining a spotlight on dark corners of the Roman forum and the disturbing frequency with which stories of sexual violence (the rape of the Sabines, the rape of Lucretia, the almost-rape of Verginia, averted only by her death) punctuate Rome’s political history.

At what point did Rome make the transition from being a rather undistinguished settlement on the river Tiber, poorer and less well connected than many of its neighbours, to being a superpower in embryo? As Beard makes clear, the empire was generated partly through the exaction of military services (rather than tribute) from subordinate allied communities, yielding a huge reserve of armed force, and in part through the competitive ideology of the Roman elite – every senator dreamed of processing through Rome at the head of a victorious army. But expansion put great power in the hands of individual commanders. It was the empire itself, Beard persuasively argues, that ultimately produced the rule of the emperors.

Beard presents a plausible picture of gradual development from a community of warlords to an urban centre with complex political institutions, institutions which systematically favoured the interests of the upper classes yet allowed scope for the votes of the poor to carry weight. We may think of the Greeks as the great originators of western political theory, but Beard emphasises the sophistication of Roman legal thought, already grappling in the late second century BC with the complex ethical issues raised by the government of subject peoples.

Structures and institutions are the dominant concern in Beard’s compelling analysis but it is constantly enlivened by gripping episodes such as the assassination of Caesar and illuminating details like the significance of Augustus’ signet ring. Central chapters focus on two key individuals: Cicero, in many ways the symbol of the Roman republic, and his younger contemporary, the enigmatic Augustus, architect of the autocratic regime that succeeded the republic. Letters and other documents also allow us glimpses of family life, of what it might mean to be a slave-secretary, of the experiences of Roman upper-class women.

Relations between the sexes could be political dynamite. Mark Antony was in thrall to Cleopatra – or so Augustus alleged of his rival. What claims, we might wonder, did Antony make about Augustus? And if the emperor Nero often figures in the top 10 “most evil men in history”, this may be more to do with his successors’ need to justify his fall from power than his actual behaviour. For the majority of inhabitants of the Roman empire, as is emphasised, it made almost no difference who was emperor.

Beard is ever alert to linguistic nuance, sharing with her readers the point of Roman jokes and nicknames, teasing out the significance of a board game or an epitaph. Artworks and literary texts played a critical role in articulating identities, communal and individual, and in making sense of power in the Roman world. Modern scholars may struggle to interpret these texts now, and though Beard is primarily focused on Rome, she does not overlook the linguistic and cultural diversity of the vast swath of territory over which the city ruled.

The widespread practice of inscribing texts on stone or bronze has preserved the words of bakers, minor magistrates and slaves, as well as those of imperial authority (Beard argues against more pessimistic estimates of literacy levels). The preoccupations of Rome’s 99% can be gleaned from Egyptian papyri, or messages to the gods on lead tablets. Ex-slaves in particular made use of funeral monuments to showcase their citizenship. Issues of identity and belonging were all the more pressing in a world where the majority of Romans had never been to Rome.

Beard makes us reconsider what we think we know about the Romans. Her book is not a seamless narrative of the rise and flourishing of the Roman empire, but a subtle and engaging interrogation of the complex and contradictory textual and material traces of the Roman world.

The most devastating critique of the Roman empire comes in an imagined speech put in the mouth of a British tribal leader (“they make a desert and call it peace”) and was penned by one of Rome’s most distinguished senators, the historian Tacitus. An anxiety about what exactly it means to be Roman seems to drive many texts of the period. This anxiety insistently resonates with the concerns of the early 21st century. As Beard explains, it is not that we should take the Romans as our models. But reflecting on the ways they perceived and organised their world is a valuable reminder that concepts we take for granted – the nation state, for instance – are the product of particular historical circumstances. And that in a globalised world, different forms of identity, of community, of attachment may succeed them.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is fact that Julius Caesar slept with Brutus's mom Servia for years but what makes that funnier is according to Plutarch in Cato the Younger in the Senate they were arguing about Caesars involvement in the Catiline conspiracy Caesar got a letter and to his credit really tried to not have it read aloud Cato pushed for and Caesar handed the letter to him the it was basically the letter of sexting and it was from Servia by the way Cato was Servia's half brother so he threw the letter back and the Senate laughed except for Brutus who was also there.

#I wonder how Servia felt after her son killed her lover of twenty years#julius caesar#brutus#cato the younger#servia#ancient rome

4 notes

·

View notes