#celebrities include the members of icp

Text

my brother is really into mlp and my ex is an artist so to upset him i commission her to draw art of our family members and random celebrities as ponies and other creatures from that show and then i print out high res copies and put them into his mailbox unlabeled whenever im in his part of town

#celebrities include the members of icp#joe biden#trump#melanie martinez#tupac#drake bell#biggie smalls#gordon freeman#the entire cast of#danganronpa#and dan schneider#among others#oh also amongus#an original#txt#mlp

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Lab Saving the World From Snake Bites

https://sciencespies.com/nature/the-lab-saving-the-world-from-snake-bites/

The Lab Saving the World From Snake Bites

In a patchy ten-acre tract of grass in Coronado, a hilly exurb northeast of the Costa Rican capital of San José, a weedy horse paddock and corrugated metal stable stand adjacent to a building of pristine laboratories and climate-controlled habitats. Through one door is a necropolis of dead snakes preserved in glass jars arranged helter-skelter on a counter, reminiscent of a macabre Victorian cabinet of curiosities. Through another is a sterile-looking white room full of humming scientific instruments.

A variety of snakes preserved at the Instituto Clodomiro Picado, in Costa Rica, a world leader in venom antidote production.

(Myles Karp)

The Instituto Clodomiro Picado, or ICP, named after the father of Costa Rican herpetology, is one of the world’s leading manufacturers of snake antivenoms, and the only one in Central America. The need for antivenoms is far more urgent than a person living in a developed nation blessed with a temperate climate might suppose. Globally, venomous snakebites kill roughly 100,000 people each year, mostly in South Asia, Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In these regions’ poorer corners, local capacities for antivenom production are limited or nonexistent; the ICP has stepped in to help fill the gaps. Beyond meeting its own country’s needs, the institute has supplied or developed lifesaving antivenoms for victims on four continents, each treatment customized to protect against species that still pose lethal threats, from the West African carpet viper to the Papuan taipan.

At one time, snakebite deaths were common in Costa Rica, as Picado himself documented in his 1931 book Venomous Snakes of Costa Rica. He reported 13 in just one month—a death rate, given the population of about 500,000, higher than the current global death rate from lung cancer. Largely because of the ICP’s antivenoms, snakebite deaths in Costa Rica today are negligible, typically one or two per year in a current population of some five million—about the same per capita death rate as powered lawn mower accidents in the United States.

Celebrated for its abundance of tropical wildlife, Costa Rica is a place where it pays to watch your step. It is home to 23 species of venomous snakes, including the Central American bushmaster—one of the world’s largest vipers, growing up to 11 feet—and the bocaracá, whose indigenous name means “devil that brings death when it bites.” Yet none is more feared than Bothrops asper—the terciopelo, also known as the fer-de-lance. Across a range extending from Mexico to northern Peru, the terciopelo is dreaded for its tenaciously defensive temperament: In situations that would cause other vipers to flee, it strikes. And when the terciopelo bites, it injects a remarkable volume of venom, around ten times as much as a copperhead.

Among the most feared snakes to inhabit Central and South America is the terciopelo, or fer-de-lance, a venomous pit viper up to eight feet long.

(Alex Hyde)

For the stricken, the result is hellish. Terciopelo venom destroys the flesh at the injection site, causing severe swelling, tissue death and excruciating pain. As it travels through the body, it induces internal bleeding and, in severe cases, organ failure and death. Blood can seep out of the nose and mouth, among other orifices, which Mayans compared to sweating blood. Picado described the late stages of such a snakebite this way: “If we ask the wretch something, he may still see us with misted eyes, but we get no answer, and perhaps a last sweat of red pearls or a mouthful of blackened blood warns us of the triumph of death.”

* * *

“Are you scared?” asked the ICP snake handler Greivin Corrales, with a touch of concern and some mild amusement. I was standing in a small room with a six-foot-long terciopelo, unrestrained on the floor, only a few feet away from me. Corrales had witnessed me tense up when he removed the snake from a bucket with a hook; I had heard of the terciopelo’s reputation. Corrales’ colleague Danilo Chacón referred to the specimen as a bicho grande, using an untranslatable term that falls somewhere between critter and beast. The snake exhibited the characteristic scale pattern of diamond and triangles in light and dark brown, and the trilateral head that inspires the common name fer-de-lance, or lancehead. Though the snake was highly conspicuous on the terrazzo tiles, the markings would blend seamlessly with Costa Rica’s forest floor, making it all too easy to step on such a bicho.

The ICP has mastered the process of antivenom production, and I had come to watch the fundamental first step: the extraction of venom from a live snake, sometimes called “milking.”

The bucket from which the snake had been drawn was full of carbon dioxide gas, which temporarily sedates the snake, making the process less stressful for both animal and handler. Chacón, the more experienced handler, only recently started using carbon dioxide after nearly 30 years working with unsedated terciopelos. “I think it’s about not getting overconfident,” said Corrales. “Once you’re too confident, you’re screwed.” Even while occasionally handling unsedated snakes, the technicians use bare hands. “You have to feel the movement,” he said. “With gloves you don’t feel the animal, you don’t have control.”

The handlers bent down and picked up the groggy terciopelo, Chacón grabbing the head, Corrales lifting the tail and midsection. They led the snake headfirst to a mechanism topped by a funnel covered with a layer of thin, penetrable film, which the snake instinctively bit. Venom dripped from the fangs, through the funnel and into a cup. In its pure form, viper venom is viscous and golden, resembling a light honey.

One challenge of producing an antidote to snake venom is that you first have to produce the venom. Above, in the serpentarium at the Instituto Clodomiro Picado, Danilo Chacón and Greivin Corrales handle a live terciopelo, Bothrops asper, after sedating it with carbon dioxide gas. The men don’t wear bite-resistant gloves because they want to feel the snake move. Above right, when they place the fangs through a film stretched over a collection tube, the reptile’s venom glands, located below its eyes, discharge the honey-colored venom through ducts, out the fangs and, far right, into a cup. Small amounts of such venom will be repeatedly injected into a horse over several months, and the horse’s immune system will generate antibodies to the venom that will serve as the basis of an antivenom treatment. Left, Chacón and Corrales open the snake’s mouth to reveal its tongue and substantial fangs.

(Myles Karp)

Antivenoms were first developed at the end of the 19th century by the French physician and immunologist Albert Calmette. An associate of Louis Pasteur, Calmette was stationed in Saigon to produce and distribute smallpox and rabies vaccines to local people. Alarmed by a surge of fatal cobra bites in the area, Calmette—who later gained fame as an inventor of the tuberculosis vaccine—applied the principles of immunization and vaccination to snake venom. He injected serial doses into small mammals in order to force their bodies to recognize and gradually develop antibodies as an immune response to the toxins in the venom. In 1895, he began producing the first antivenoms by inoculating horses with Asian cobra venom, drawing the horses’ blood, separating the venom-resistant antibodies, and mixing them into a fluid that could be injected into a snakebite victim.

An institute staff member checks the temperature of a horse involved in generating antibodies to snake venom it has been exposed to. Technicians will collect the horse’s blood and separate off the antibody-rich plasma, which is purified, sterilized and packaged as an antivenom. The institute produces about 100,000 vials of antivenom annually, for treating people in Central and South America and sub-

Saharan Africa.

(The Instituto Clodomiro Picado)

Today, the ICP produces antivenoms in much the same way, but with more advanced processes allowing for a purer product. “Our antivenoms are basically solutions of horse antibodies specific against particular venoms,” said José María Gutiérrez, a former director of the ICP and a professor emeritus at the University of Costa Rica, which oversees the institute. The ICP’s roughly 110 horses live mostly on a farm in the nearby cloud forest and are brought to the stables to take part in antivenom production periodically. Venom is injected into a horse’s body in tiny amounts every ten days for two or three months initially, then once every two months—enough for its immune system to learn to recognize and create antibody defenses against the venom over time, but not enough to harm the horse. Afterward, blood is extracted from the horse in a quantity that is “like donating blood at a blood bank,” according to Gutiérrez. “We have the horses under strict veterinary control.”

Once the blood settles, the antibody-containing plasma is separated, purified, filtered, sterilized and mixed into a neutral liquid. The antivenoms are sent to hospitals, clinics and primary health posts, where they are diluted with saline and administered intravenously into snakebite victims.

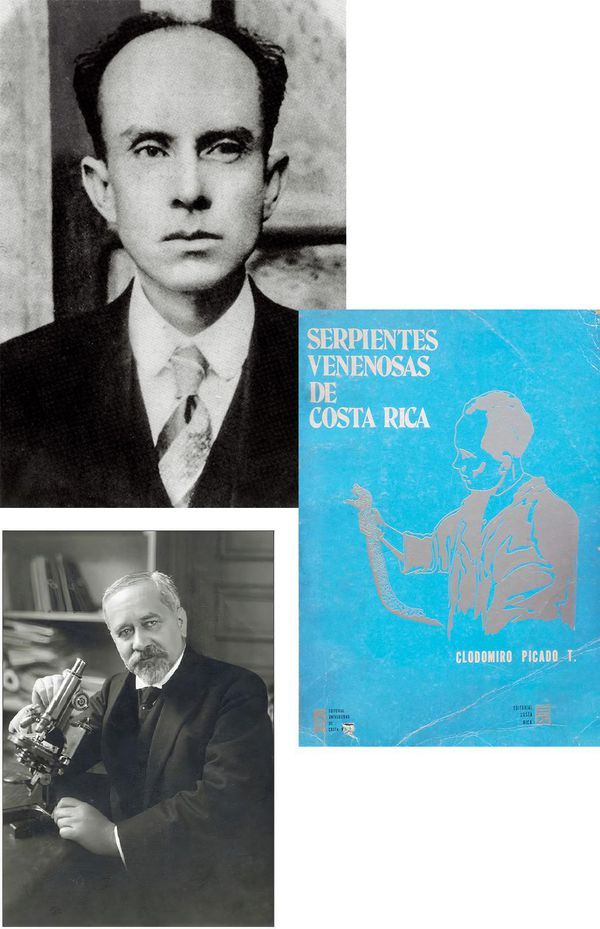

Top, Clodomiro Picado, who was reared in Costa Rica and studied in France, was a zoologist, botanist and author of a 1931 book, left, about venomous snakes. He worked at a time when snakebites were a significant cause of death in Costa Rica. Far left, Albert Calmette, c. 1920, a French physician celebrated for his contribution to the tuberculosis vaccine, produced the first snakebite antidote in 1895, having studied venomous snakes while stationed in Saigon for the Pasteur Institute.

(The Instituto Clodomiro Picado (2); © Institut Pasteur – Musée Pasteur)

Antivenom counteracts venom precisely on a molecular level, like a lock and key. Because venoms vary chemically among species, an antivenom to protect against a specific snake’s bite must be prepared with venom from that snake, or from one that has very similar venom. To produce an antivenom that protects against multiple species, called a “polyvalent,” different venoms must be combined strategically in production. “That specificity makes anti-venoms sort of difficult to produce,” said Gutiérrez. “In contrast, tetanus antitoxin is the same all over the world, because tetanus toxin is a single toxin.”

The ICP maintains a diverse collection of live snakes, mostly caught and donated by Costa Rican farmers and landowners, some bred in captivity. From these, the ICP technicians have built an impressive stock of extracted venoms, supplemented with occasional imports of exotic venoms.

“Venom, more venom, and more venom there,” said serpentarium coordinator Aarón Gómez, opening a freezer in a laboratory room, exposing dozens of samples. After extraction, most of the venoms are immediately dehydrated for preservation. He unscrewed the top of a plastic container the size of a spice jar, revealing contents that looked like yellow ground mustard powder. “That’s terciopelo venom,” he said. “We have 1.5 kilos,” he said with raised eyebrows. That’s enough to kill 24 million mice or probably thousands of people.

The snakes that produce the world’s most potent venoms inhabit deserts, tropical forests and warm seas. Many pose a grave threat to people, but others are seldom encountered. Below the map, learn about ten of the most lethal snakes, ranked in descending order by venom potency. —Research by Katherine R. Williams

(Eritrea Dorcely)

Enhydrina schistosa

(Alamy)

Lethal venom dose*: 0.6 micrograms

Venom yield**: 79 milligrams

Common name(s): Beaked sea snake, hook-nosed sea snake, Valakadyn sea snake

This highly aggressive species kills more humans than any other sea snake. Its venom is so potent that one animal may carry enough to kill as many as 22 people.

*Estimated amount of venom, in micrograms, to kill 50 percent of laboratory mice in a sample, if each mouse weighed 30 grams. A microgram is 0.001 milligram, roughly the mass of a single particle of baking powder.

**Maximum amount of venom, dried, in milligrams, produced at one time by an adult snake.

The ICP’s success in maintaining and breeding snakes that otherwise fare poorly in captivity has allowed for the collection to include workable quantities of exceedingly rare venoms. For example, an innovative technique involving a diet of tilapia filets sustains about 80 coral snakes in the serpentarium, a rare quantity. “Most other producers don’t produce coral antivenom,” said Gómez. “But because we have the snakes, we can produce the venom, so we can produce the antivenom.” A potent neurotoxin, coral snake venom is about four times as lethal as terciopelo venom. In powdered form, it is pure white.

* * *

There’s no question that historical factors like accessible health care, the migration from rural to urban areas, and even a decrease in barefootedness contributed to the decline of snakebite deaths in Costa Rica. But without the ICP’s antivenoms, bites would still carry a grave risk. Traditional remedies popular before the proliferation of antivenoms—such as drinking an elixir of tobacco leaf or rubbing a bone on the bite—were no match for snake venom.

At a Doctors Without Borders clinic in Abdurafi, Ethiopia, a 24-year-old farmworker received antivenom after a snake bit her on the forehead as she slept.

(MSF)

Other countries, however, cannot claim such progress. India alone suffers nearly 50,000 venomous snakebite fatalities each year, chiefly from the saw-scaled viper, the Indian cobra, Russell’s viper and the common krait. Nigeria’s snakebite mortality rate has been reported at 60 deaths per 100,000 people—more than five times the mortality rate from automobile accidents in the United States.

A combination snakebite treatment produced by the Costa Rican institute consists of antibodies to three venomous snakes that inhabit sub-Saharan Africa.

(Susanne Doettling / MSF)

“We want to expand the knowledge and expertise generated in Costa Rica to contribute to solving this problem in other regions and countries,” said Gutiérrez, who is also a member of the board of directors of the Global Snakebite Initiative, a nonprofit that advocates for greater recognition and understanding of snakebite mortality worldwide, especially in impoverished regions. Since the near-eradication of snakebite deaths in Costa Rica, the ICP has endeavored to fill antivenom vacuums in these faraway places where antivenoms have been inadequate, inaccessible or nonexistent.

Even the United States, with its advanced medical science and robust pharmaceutical industry, has experienced occasional antivenom shortages. Despite the exorbitant prices for which the product can be sold in the U.S.—generally over 100 times what ICP antivenoms go for—the relative rarity of venomous bites and the esoteric, labor-intensive manufacturing process have kept antivenom production a niche industry there. Only two entities in the United States currently produce snake antivenoms for human use: Pfizer (to counteract coral snake venom) and Boston Scientific (to counteract pit vipers like rattlesnakes).

Clark’s coral snake, native to rainforests in parts of Costa Rica, Panama and Colombia, is nocturnal and doesn’t often trouble people. ICP scientists have decoded its venom and found three toxic compounds.

(Alamy)

That leaves labs like the ICP fulfilling the supply of antivenoms where the demand is greatest. Founded in 1970, ICP began steadily furnishing the drugs to other Central American countries in the 1990s. To develop new antivenoms for regions in need, in the early 2000s it began importing foreign venoms with which to inoculate its own horses; the institute doesn’t import live snakes because of ecological and safety concerns.

For a decade the institute has been distributing a newly developed antivenom to Nigeria, capable of protecting against the venoms of the West African carpet viper, the puff adder and the black-necked spitting cobra. Bites from these deadly snakes had been treated in the past mostly with a polyvalent antivenom manufactured by Sanofi-Pasteur, but the French pharmaceutical giant, citing a lack of profit, ceased production in 2014, leaving a dangerous gap in the market. The ICP’s antivenom is now being used in other countries in the region, from Burkina Faso to the Central African Republic. “Doctors Without Borders is now using our antivenom at their stations in Africa,” said Gutiérrez.

Named for the unusual scales protruding from its head, the eyelash viper is a venomous tree snake found from southern Mexico to Venezuela.

(The Instituto Clodomiro Picado)

“The Instituto Clodomiro Picado has been doing this production for many, many years, and they’ve got it dialed in,” said Steve Mackessy, a biochemist from the University of Northern Colorado, who has collaborated with the institute. “They produce an affordable product that works very, very well. So applying that to a situation where you have anti-venoms that either weren’t available at all, or were poor quality, or poor efficacy because they’re mostly designed against other species, that’s a godsend for those countries.”

An estimated 250,000 people have been treated with ICP’s antivenoms in Central America, South America, Africa and the Caribbean. The institute has recently developed new products for Asia, specifically Papua New Guinea—home to the extremely venomous taipan—and Sri Lanka, where imported Indian antivenoms used there have been described as largely ineffective.

The largest venomous snake in the New World is the bushmaster—here, the Central American species, which may grow to 11 feet. Its inch-long fangs inject prey with copious venom.

(The Instituto Clodomiro Picado)

Antivenoms may not be a lucrative business, but Gutiérrez stresses that access to such essential medicines should be considered a human right rather than a commodity. “This is a philosophical issue here,” he said. “Any human being that suffers snakebite envenomation should have the right to receive an antivenom.”

* * *

Clodomiro Picado himself—whose imposing bust adorns a sign outside the ICP’s entrance—was not generous in his estimation of the character of snakes. “He who dies victim of snakes does not fight, his death won not by conquest but by thievery,” he wrote. “For this reason the serpent, together with poison and the dagger, are signs of treachery and treason.” Gutiérrez is more measured, pointing out that snakes have been both gods and demons in mythologies around the world: “They’re fascinating, yet they can kill you.”

#Nature

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

'Magnum Photos at 70' — celebrating seven decades of visual storytelling

On Feb. 6, 1947, four photographers — Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and David “Chim” Seymour — toasted the founding of what would become the world’s most influential artist collective over a celebratory magnum of champagne in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. In the past 70 years, 92 photographers have contributed to the story of Magnum Photos, and today 49 photographer members continue to chronicle the world, interpreting its people, events and issues through visual storytelling.

Magnum Photos is celebrating 70 years of contribution to photography and world history with a special anniversary program marking its legacy, community, and contemporary photographic practices: public events, exhibitions — notably “Magnum Manifesto” at the International Center of Photography (ICP) and an accompanying catalogue published by Thames & Hudson — new photographic projects and a series of exclusive digital launches.

“Magnum Manifesto” traces the ideas and ideals behind the founding and development of the cooperative. It explores the history of the second half of the 20th century through the lenses of 75 masters, providing a new and insightful perspective on the contribution of these photographers to our collective visual memory.

Featuring group and individual projects, the exhibition includes more than 200 prints as well as books, magazines, videos and archival documents that have rarely been seen before. Among many others, it features the work of Christopher Anderson, Jonas Bendiksen, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Cornell and Robert Capa, Chim (David Seymour), Raymond Depardon, Bieke Depoorter, Elliott Erwitt, Martine Franck, Leonard Freed, Paul Fusco, Cristina García Rodero, Burt Glinn, Jim Goldberg, Joseph Koudelka, Sergio Larrain, Susan Meiselas, Wayne Miller, Martin Parr, Marc Riboud, Alessandra Sanguinetti, W. Eugene Smith, Alec Soth, Chris Steele-Perkins, Dennis Stock, Mikhael Subotzky and Alex Webb.

The exhibition is a coproduction between ICP and Magnum Photos. It is curated by Clément Chéroux, formerly photography curator at the Centre Pompidou, now senior curator of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, with Clara Bouveresse and ICP associate curator Pauline Vermare.

“Magnum: 70 at 70,” a NeueHouse exhibition of 70 pictorial and historical photographic icons, celebrates the diversity of the Magnum photographers bearing witness to major events of the last 70 years. Including seminal works by Susan Meiselas, Paolo Pellegrin, Martin Parr and Christopher Anderson, the exhibition spans the globe and covers regional events such as the Arab Spring, South Africa under apartheid and the recent migration crisis. (Magnum Photos)

“Magnum Manifesto” can be seen at ICP through Sept. 3.

“Magnum: 70 at 70” can be seen at NeueHouse, public open hours on the weekends, by appointment, 12 p.m.-6 p.m., through Sept. 3. Register at [email protected].

Photos from top: © Josef Koudelka/Magnum Photos, © Alessandra Sanguinetti/Magnum Photos, © Alex Majoli/Magnum Photos

See more photos of 'Magnum Photos at 70' and our other slideshows on Yahoo News.

#magnum photos#josef koudelka#Jonas Bendiksen#alex majoli#leonard freed#marc riboud#paul fusco#chris steele-perkins#alessandra sanguinetti#70th anniversary#icp#neuehouse#photography#photojournalism

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Debunking the Myths of Robert Capa on D-Day

I want to give you a brief overview of an investigation that began almost five years ago, led by me but involving the efforts of photojournalist J. Ross Baughman, photo historian Rob McElroy, and ex-infantryman and amateur military historian Charles Herrick.

Our project, in a nutshell, dismantles the 74-year-old myth of Robert Capa’s actions on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and the subsequent fate of his negatives. If you have even a passing familiarity with the history of photojournalism, or simply an awareness of twentieth-century cultural history on both sides of the Atlantic, you’ve surely heard the story; it’s been repeated hundreds, possibly thousands of times:

Robert Capa landed on Omaha Beach with the first wave of assault troops at 0630 on the morning of June 6, 1944 (D-Day), on freelance assignment from LIFE magazine.

He stayed there for 90 minutes, until he either inexplicably ran out of film or his camera jammed.

During that time he made somewhere between 72 and 144 35mm b&w exposures of the Allied invasion of Normandy on Kodak Super-XX film.

Upon landing back in England the next day, he sent all his film via courier to assistant picture editor John Morris at LIFE’s London office, instead of delivering it in person.

This shipment included pre-invasion reportage of the troops boarding and crossing the English Channel, the just-mentioned coverage of the battle on Omaha Beach, and images of medics tending to the wounded on the return trip.

When the film finally arrived, around 9 p.m., the head of LIFE’s London darkroom, one “Braddy” Bradshaw, inexplicably assigned the task of developing these crucial four rolls of 35mm Omaha Beach images to one of the least experienced members of his staff, 15-year-old “darkroom lad” Denis Banks.

After successfully processing the 35mm films, in his haste to help Morris meet the looming deadline Banks absentmindedly closed the doors of the darkroom’s film-drying cabinet, which inexplicably were “normally kept open.” Inexplicably, nobody noticed that Banks had closed them.

As a result, after “just a few minutes,” that enclosed space with a small electric heating coil on its floor inexplicably became so drastically overheated that it melted the emulsion of Capa’s 35mm negatives.

Notified of this by the horrified Banks, Morris rushed to the darkroom, discovering that eleven of Capa’s negatives had survived, which he “saved” or “salvaged,” and which proved just sufficient enough to fulfill this crucial assignment to the satisfaction of LIFE’s New York editors.

That darkroom catastrophe blurred slightly the remaining negatives, “ironically” adding to their expressiveness. Furthermore, as a result of the overheating, the emulsion on those eleven negatives inexplicably slid a few millimeters sideways on their acetate backing, resulting in a visible intrusion of the film’s sprocket holes into the image area.

Robert Capa, D-Day images from Omaha Beach, contact sheet, screenshot from TIME video (May 29, 2014), annotated.

That standard narrative constitutes photojournalism’s most potent and durable myth. From it springs the image of the intrepid photojournalist as heroic loner, risking all to bear witness for humanity, yet at the mercy of corporate forces that, by cynical choice or sheer ineptitude, can in an instant erase from the historical record the only traces of a crucial passage in world events.

Jean-David Morvan and Séverine Tréfouël, “Omaha Beach on D-Day” (2015), cover

Moreover, it represents, arguably, the most widely familiar bit of folklore in the history of the medium of photography — one that appears not only in histories of photography and photojournalism, in biographies of and other books about Capa, but in novels, graphic novels, the autobiographies of such famous people as actress Ingrid Bergman and Hollywood director Sam Fuller, assorted films, and even in videos of Steven Spielberg talking about his inspirations for the opening scenes of his film Saving Private Ryan, not to mention countless retellings in the mass media.

Charles Christian Wertenbaker, “Invasion!” (1944), cover

An early version of this story started to circulate immediately after D-Day, made its first half-formed appearance in print in the fall of 1944, and received its full formal authorization with the publication of Capa’s heavily fictionalized memoir, Slightly Out of Focus, in the fall of 1947. Since then it’s been reiterated endlessly, either by John Morris or by others quoting or paraphrasing Capa’s or Morris’s version of the tale. It gets retold in the mass media with special frequency on every major celebration of D-Day — the 50th anniversary, the 60th, most recently the 70th. In short, it has gradually achieved the status of legend. That this legend went unexamined for seven decades serves as a measure of its appeal not just to photojournalists, to others involved professionally with photography, and to the medium’s growing audience, but to the general public.

For 70 years, despite the many glaring holes in it, no one questioned this story — least of all those in charge at the International Center of Photography, which houses the Capa Archive. These figures have included the late Cornell Capa, Robert’s younger brother and founder of ICP; the late Richard Whelan, Robert’s authorized biographer and the first curator of that archive; and Whelan’s successor in that curatorial role, Cynthia Young.

Ironically, two celebrations of the 70th anniversary of Capa’s D-Day images provoked our investigation. The first came as a flattering profile of John Morris, written by Marie Brenner for Vanity Fair magazine. Morris served as assistant picture editor in LIFE’s London bureau for that magazine’s D-Day coverage, and in this Brenner piece he recounts his version of the Capa-LIFE D-Day myth once more. Shortly thereafter, on May 29, 2014, TIME Inc. — the corporation that had commissioned and published Capa’s D-Day images back in 1944 — posted a video at its website celebrating those photographs, which some refer to as “the magnificent eleven.”

A division of Magnum Photos, the picture agency Capa founded with his colleagues in 1947 (the same year he published his memoir), produced that video for TIME. The International Center of Photography licensed the use of Capa’s images for that purpose. And none other than John Morris, by then 97 years old and living in Paris, provided the voice-over, his boilerplate narrative of those events. In short, this video involved the combined energies of the individual and institutional forces involved in the creation and propagation of this myth — what I came to define as the Capa Consortium.

The Capa Consortium, Keynote slide, © 2015 by A. D. Coleman

Assorted elements of those two virtually identical versions of the standard story, Brenner’s and Time Inc.’s, struck J. Ross Baughman as illogical and implausible. The youngest photojournalist ever to win a Pulitzer Prize (in 1978, at the age of 24), Baughman is an experienced combat photographer who has worked in war zones in the Middle East, El Salvador, Rhodesia, and elsewhere. As the founder of the picture agency Visions, which specialized in such work, he’s also an experienced picture editor. Ross contacted me to ask if I would publish his analysis at my blog, Photocritic International, as a Guest Post. I agreed.

In the editorial process of fact-checking and sourcing Baughman’s skeptical response to the standard narrative provided by Morris in that video, my own bulls**t detector began to sound the alarm. I realized that Baughman’s critique raised more questions than it answered, requiring much more research and writing than I could reasonably request from him. I decided to pursue those issues further myself.

This immersed me in the Capa literature for the first time. Speaking as a scholar, that came as a rude awakening. The most immediate shock hit as I read through a half-dozen print and web versions of Morris’s account of those events — in Brenner’s 2014 puff piece, in Morris’s 1998 memoir, and in various interviews, profiles, and articles — and watched at least as many online videos and films featuring Morris rehashing this tale. I realized that the only portion of this story that Morris claimed to have witnessed firsthand, the loss of Capa’s films in LIFE’s London darkroom, could not possibly have happened the way he said it did.

In retrospect, I cannot understand how so many people in the field, working photographers among them, accepted uncritically the unlikely, unprecedented story, concocted by Morris, of Capa’s 35mm Kodak Super-XX film emulsion melting in a film-drying cabinet on the night of June 7, 1944.

Anyone familiar with analog photographic materials and normal darkroom practice worldwide must consider this fabulation incredible on its face. Coil heaters in wooden film-drying cabinets circa 1944 did not ever produce high levels of heat; black & white film emulsions of that time did not melt even after brief exposure to high heat; and the doors of film-drying cabinets are normally kept closed, not open, since the primary function of such cabinets is to prevent dust from adhering to the sticky emulsion of wet film.

No one with darkroom experience could have come up with this notion; only someone entirely ignorant of photographic materials and processes — like Morris — could have imagined it. Embarrassingly, none of that set my own alarm bells ringing until I started to fact-check the article by Baughman that initiated this project, close to fifty years after I first read that fable in Capa’s memoir.

This is one of several big lies permeating the literature on Robert Capa. Certainly Capa knew it was untrue when he published it in his memoir; he had gotten his start in photography as a darkroom assistant in Simon Guttmann’s Dephot photo agency in Berlin. And Cornell Capa also knew that; he had cut his eyeteeth in the medium first by developing the films of his brother, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and David Seymour in Paris, then by working in the darkroom of the Pix photo agency in New York, then by moving on to fill the same role at LIFE magazine before becoming a photographer in his own right. My belated recognition of that fact led me to ask the obvious next question: If that didn’t happen to Capa’s 35mm D-Day films, what did? And if all these people were willing to lie about this, what were they covering up?

So, building on Baughman’s initial provocation, I began drafting my own extensions of what he’d initiated — and our investigation was launched.

In December of 2017 I published the 74th chapter of our research project. You’ll find all of it online at my blog; the easiest way to get to the Capa D-Day material is by using the url capadday.com. During these years I have become intimately familiar with a large chunk of what others have written and said about Capa and his D-Day coverage.

In my opinion, the bulk of the published writing and presentations in other formats (films, videos, exhibitions) devoted to the life and work of photojournalist Robert Capa qualifies as hagiography, not scholarship. Capa’s own account of his World War II experiences, Slightly Out of Focus, consistently proves itself inaccurate and unreliable, masking its sly self-aggrandizement with wry humor and self-deprecation. Morris’s memoir repeats Capa’s combat stories unquestioningly, adding to those his own dubious saga of the “ruined” negatives.

Richard Whelan, “This Is War! Robert Capa at Work” (2007), cover

Richard Whelan’s books, widely considered the key reference works on Capa, simply quote or paraphrase Capa and Morris uncritically, perhaps because they were sponsored, subsidized, published, and endorsed most prominently and extensively by the estate of Robert Capa and the Fund for Concerned Photography (both controlled by Capa’s younger brother Cornell) and the International Center of Photography, founded by Cornell, who also served as ICP’s first director.

Produced in most other cases under Cornell’s watchful eye or the supervision of one or another participant in the Capa Consortium, the remainder of the serious, scholarly literature on Robert Capa has almost all been subject to Cornell’s approval and reliant on either the problematic principal reference works or on Robert Capa materials stored in Cornell’s private home in Manhattan, with access dependent on his consent. Consequently, it constitutes an inherently limited corpus of contaminated research, fatally corrupted by its unswerving allegiance to both its patron and its patron saint. Such bespoke scholarship becomes automatically suspect.

Cornell Capa, interview with Barbaralee Diamonstein, 1980, screenshot

The second failing of this heap of compromised materials resides in its reliance on untrustworthy and far from neutral sources: Robert Capa, with a demonstrated penchant for self-mythification; his younger brother Cornell, a classic “art widower” with every reason to enhance his brother’s reputation; and Robert’s close friend and Cornell’s, John Morris, whose own stature in the field premises itself on the Capa D-Day legend. Only Alex Kershaw’s unauthorized Capa biography, Blood and Champagne, published in 2002, maintains its independence from Cornell’s influence, but at the cost of losing access to the primary research materials and consequently reiterating the erroneous information in the accounts of Capa, Morris, and Whelan. Virtually everything else published about Capa, including those stories in the mass media that appear predictably every five years along with celebrations of D-Day, unquestioningly presents the prevailing myth.

This Capa literature suffers from a third fundamental flaw: Those generating it (with the exception of Capa himself and his brother Cornell), have no direct, hands-on knowledge of photographic production, no military background (significant in that Robert Capa’s most important work falls under the heading of combat photography), and no forensic skills pertinent to the analysis of photographic materials. Nor were they encouraged by their patron, Cornell Capa, to make up for those deficiencies by involving others with those competencies in their projects. Instead, their privileged relationship to the primary materials, along with the availability of a prominent and well-funded platform at ICP, enabled them to effectively invent whatever suited them, pleased their benefactor, and served their purposes.

Responsible Capa scholarship, therefore, must begin by distrusting the extant literature, turning instead to the photographs themselves and relevant documents that the Capa estate and ICP do not control and to which they therefore cannot prohibit access. Those materials lie at the core of our research project.

Here’s a short summary of what we’ve found:

Capa sailed across the English Channel on the U.S.S. Samuel Chase.

According to the official history of the U.S. Coast Guard, fifteen waves of LCVPs (commonly called Higgins boats) carrying troops left the U.S.S. Samuel Chase for Omaha Beach that morning. Capa almost certainly rode in with Col. Taylor and his staff, the command group of Company E of the 16th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 1st Division, to which Capa had been assigned. They constituted part of the thirteenth wave.

That wave arrived at the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach at 8:15, a half hour after the last of the 16th Infantry Regiment’s nine rifle companies. We can see from Capa’s images that numerous waves of troops preceded them.

Using distinctive landmarks visible in Capa’s photos, Charles Herrick has pinpointed exactly where Capa landed on Easy Red: the beach at Colleville-sur-Mer. Gap Assault Team 10 had charge of the obstacles in that sector. An existing exit off this sector made it possible to reach the top of the bluffs with relative ease. Col. Taylor would become famous for announcing to the hesitant troops he found there, “Two kinds of people are staying on this beach, the dead and those who are going to die — now let’s get the hell out of here,” and urging them up the Colleville-sur-Mer draw to the bluffs.

Robert Capa, CS frame 4, neg. 32, detail, annotated

Fortuitously, that stretch of Easy Red represented a seam in the German defenses, a weak point at the far end of the effective range of two widely separated German blockhouses. Both cannon fire and small-arms fire there proved relatively light — one reason for the success of Gap Assault Team 10 in clearing obstacles in that area. This explains why, contrary to LIFE’s captions and Capa’s later narrative, his images show no carnage, no floating bodies and body parts, no discarded equipment, and no bullet or shell splashes. This also explains why the Allies broke through early at that very point.

Capa did not run out of film, nor did his camera jam, nor did seawater damage either his cameras or his film. In his memoir, Capa first implies that he exposed at most two full rolls of 35mm film — one roll in each of his two Contax II rangefinder cameras, 72 frames in all — at Omaha Beach. By the end of that chapter, this has somehow grown to “one hundred and six pictures in all, [of which] only eight were salvaged.” John Morris claims he received 4 rolls of Omaha Beach negatives from Capa. We find no reason to believe that Capa made more than the ten 35mm images of which we have physical evidence.

Capa made the first five of those images while standing for almost two minutes on the ramp of the landing craft that brought him there. In them we see Capa’s traveling companions carrying not small-arms assault weapons but bulky oilskin-wrapped bundles, most likely radios and other supplies for the command post they meant to establish.

Capa made his sixth exposure from behind a mined iron “hedgehog,” one of many such obstacles protecting what Nazi Gen. Erwin Rommel called the “Atlantic Wall.” He made his last four exposures — including “The Face in the Surf” — from behind Armored Assault Vehicle 10, which was sitting in the surf shelling the gun emplacements on the bluffs.

Capa described Armored Assault Vehicle 10, which appears on the left-hand side of several of his images, as “one of our half-burnt amphibious tanks.” In fact, it was a modified American tank, a “wading Sherman,” not amphibious (merely waterproofed to the top of its treads) and not burnt out; later images made by others of that stretch of Easy Red show this tank undamaged, closer to the dry beach, and apparently in action. Taken in conjunction with the known presence at that point of Gap Assault Team 10, the large numeral 10 on this vehicle’s rear vent suggests that it was a so-called “tank dozer,” one of which landed with each demolition team that morning. The U.S. Army had modified these tanks by adding detachable bulldozer “blades,” so that they could clear the debris after the engineers blew up the obstacles.

Not incidentally, both the time and place of Capa’s arrival on Easy Red contradict the current identification of Huston “Hu” Riley as “The Face in the Surf” in Capa’s penultimate exposure on Easy Red, as well as the earlier identification of “The Face in the Surf” as Pfc. Edward J. Regan. Both these soldiers arrived at different times than Capa, and on different sections of the beach. Thus the identity of “The Face in the Surf” remains unknown.

After no more than 30 minutes on the beach, and perhaps as little as 15 minutes there, Capa ran to a landing craft, LCI(L)-94, where he took shelter before its departure around 0900.

Capa claimed that he reached the dry beach and then experienced a panic attack, causing him to escape from the combat zone. We must consider the possibility that he suffered from what they then called “shell shock” and we now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). But we must also consider the possibility that, even before setting forth that morning, Capa made a calculated decision to leave the battlefield at the first opportunity, in order to get his films to London in time to make the deadline for LIFE’s next issue; if he missed that deadline, any images of the landing would become old news and his effort and risks in making them would have been for naught.

No fewer than four witnesses place Capa on this vessel, LCI(L)-94. The first three were crew members Charles Jarreau, Clifford W. Lewis, and Victor Haboush. According to Capa, once he reached LCI(L)-94 he put away his Contax II, working thenceforth only with his Rolleiflex. One of the 2–1/4″ images he made while aboard this vessel, published in the D-Day feature story in LIFE, shows Haboush assisting a medic treating a casualty.

Robert Capa, “Untitled (Medics at Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944).” Annotated screenshot from magnumphotos.com. Victor Haboush indicated by red arrow.

The fourth witness to Capa’s presence on LCI(L)-94 was U.S. Coast Guard Chief Photographer’s Mate David T. Ruley. Ruley, a Coast Guard cinematographer assigned to film the invasion from the vantage point of this vessel, coincidentally documented its arrival at the very same spot at which Capa landed, recording the same scene from a perspective slightly different from Capa’s at approximately the same time Capa made his ten exposures.

Robert Capa, “The Face in the Surf” (l); David Ruley, frame from D-Day film (r)

Ruley’s color footage appears frequently in D-Day documentaries. Charles Herrick and I verified that these film clips described conditions at that same sector of Easy Red while Capa was there. Ruley’s name on his slateboard at the start of several clips enabled us to learn a bit more about him and his assignment.

Robert Capa, center rear, aboard LCVP from USS Samuel Chase, with camera during transfer of casualty, D-Day, frame from film by David T. Ruley

Most importantly, this resulted in the discovery of brief glimpses of Capa himself, holding Ruley’s slateboard in one scene and photographing the offloading of a casualty from LCI(L)-94 to another vessel in the second clip. These are the only known film or still images of Capa on D-Day, the only film images of him in any combat situation, and among the few known color film clips of him.

Robert Capa holding cinematographer’s slate aboard LCI(L)-94, D-Day, frame from film by David T. Ruley

Cinematographer David T. Ruley, illustrations for first-person account of D-Day experiences, Movie Makers magazine, 6/1/45

By noon the battle there was largely over, and Capa had missed most of it.

He made the return trip to England aboard the U.S.S. Samuel Chase.

Arriving back in Weymouth on the morning of June 7, Capa had to wait for the offloading of wounded from the Chase before he got ashore sometime around 1 p.m. He sent all his film via courier to picture editor John Morris at LIFE’s London office, instead of carrying it himself to ensure its safe delivery and thus enable Morris to face with confidence the imminent, absolute deadline of 9 a.m. on June 8.

As a result, Capa’s films did not reach the London office till 9 p.m. that night, putting Morris and the darkroom staff in crisis mode.

Capa’s shipment included substantial pre-invasion reportage of the troops boarding and crossing the English Channel, his skimpy coverage of the battle on Omaha Beach, and several images of the beach seen from a distance, made while departing on LCI(L)-94, as well as photos of medics tending to the wounded on the return trip aboard the Chase.

In addition to several rolls of 120 film, and a few 4×5″ negatives made on shipboard with a borrowed Speed Graphic, Capa sent Morris at least five rolls of 35mm film, and possibly a sixth.

These include two rolls made while boarding and on deck in the daytime, two more of a below-decks briefing, a (missing) roll of images made on deck at twilight during the crossing, and the ten Omaha Beach exposures, plus four sheets of sketchy handwritten caption notes.

All of these films — including all of Capa’s Omaha Beach negatives — got processed normally, without incident. The surviving negatives, housed in the Capa Archive at ICP, show no sign of heat damage. Thus no darkroom disaster occurred, no D-Day images got lost … and none got “saved” or “salvaged.”

In his memoir, Capa wrote that by the time he got back to Omaha Beach on June 8 and joined his press corps colleagues, “I had been reported dead by a sergeant who had seen my body floating on the water with my cameras around my neck. I had been missing for forty-eight hours, my death had become official, and my obituaries had just been released by the censor.” No correspondent has ever corroborated that story. No such obituary ever saw print (as it surely would have), no copy thereof has ever surfaced, and no record of it exists in the censors’ logs. Purest fiction, meant for the silver screen.

So much for the myth.

We learned a few other things along the way:

LIFE magazine ran the best five of Capa’s ten 35mm Omaha Beach images in the D-Day issue, datelined June 19, 1944, which hit the newsstands on June 12. (The other five were all mediocre variants of the ones they published.)

“Beachheads of Normandy,” LIFE magazine feature on D-Day with Robert Capa photos, June 19, 1944, p. 25 (detail)

The accompanying story claimed that “As he waded out to get aboard [LCI(L)-94, Capa’s] cameras got thoroughly soaked. By some miracle, one of them was not too badly damaged and he was able to keep making pictures.” That wasn’t true, of course. Capa returned immediately to Normandy, landing back there on June 8 and continuing to use the same undamaged equipment with which he’d started out.

No sheet of caption notes for Capa’s ten Omaha Beach images in Capa’s own hand exists in the International Center of Photography’s Capa Archive. Presumably he provided none. Morris himself must have provided some — drafted hastily on the night of June 7 — for both the set that he sent to LIFE and the set that he provided to the press pool; that was required of him by his employer and by the pool. As for the captions that appeared with Capa’s pictures in the June 19 issue, Richard Whelan writes, “Dennis Flanagan, the assistant associate editor who wrote the captions and text that accompanied Capa’s images in LIFE, recalls that he depended on the New York Times for background information, and for specifics he interpreted what he saw in the photographs.”

Thus the wildly inaccurate captions that (to use Roland Barthes’s term) “anchor” Capa’s images in LIFE’s D-Day issue, and on which most subsequent republications of these images rely, either got revised from John Morris’s last-minute inventions in London or written entirely from scratch by someone in the New York office, even further removed from the action.

LIFE’s captions indicated that the soldiers seen gathered around the obstacles were hiding from enemy fire. That was also untrue. Instead, we discovered that their insignias identify them as members of Combined Demolitions Unit 10, part of the Engineer Special Task Force, busy at their assigned task of blowing up the obstacles planted in the surf by the Germans in order to clear lanes for the incoming landing craft, so that they could deposit more troops and materiel on the beachhead.

Robert Capa, D-Day negative 35, detail, annotated

The demolition team that cleared this section of Omaha Beach, Easy Red, had more success than all the other demolition teams combined. In many ways, they saved the day for the Allies — at a high cost: these engineers as a group suffered the highest casualty rate of any class of troops on Omaha Beach. Capa’s failure to provide caption notes for these exposures resulted in 70 years of misidentification of these heroic engineers as terrified assault troops pinned down and hiding behind those “hedgehogs.”

We learned that ICP had a habit of obstructing any research into the life and work of Robert Capa that did not conform to Cornell Capa’s and Richard Whelan’s censorious requirements. ICP refused to allow British military historian Alex Kershaw to access any of the materials in the Capa Archive, and refused to grant his publishers permission to reproduce any Capa images in his unauthorized biography, published in 2002. ICP also refused to allow French documentary filmmaker Patrick Jeudy to use any of the primary Capa materials they controlled in his remarkable 2004 film, Robert Capa, l’homme qui voulait croire à sa légende (“Robert Capa: The Man Who Believed His Own Legend”). Upon the film’s release, Cornell Capa persuaded John Morris to sue Jeudy in France, in an unsuccessful attempt to block its distribution.

Robert Capa, “ruined” frames from D-Day, June 6, 1944. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

We also discovered that TIME Inc. had authorized the creation of unlabelled digital fakes of Capa’s supposedly “ruined” and discarded Omaha Beach negatives, for insertion into that May 2014 video commissioned from Magnum in Motion, the multimedia division of Magnum Photos, to celebrate the 70th anniversary of D-Day. Our disclosure of this deception forced TIME to acknowledge the fakery and revise that video overnight.

Richard Whelan, “Robert Capa: In Love and War” (2003), screenshot

Finally, we discovered that Capa’s authorized biographer, the late Richard Whelan, lied outright about the emulsion sliding on Capa’s D-Day negatives (among other things). And Cynthia Young, his successor as curator of the Capa Archive at the International Center of Photography, not only repeated his lie but plagiarized it in a 2013 text of her own.

Cynthia Young, “The Story Behind Robert Capa’s Pictures of D-Day,” June 6, 2013, screenshot from ICP website 2014–06–12 at 11.38.23 AM

Many of Capa’s rolls of film from the 1940s — and not just those he made on D-Day — show the exposure overlapping the sprocket holes. This resulted from a mismatch between Kodak 35mm film cassettes and the design of the Contax II, the camera Capa used that day, and not from any damage to the films.

Top: Contax camera loaded with shorter Kodak cassette showing sprocket holes being exposed. Bottom: Capa negative shown with proper orientation as it would have appeared in the camera. Note exposed sprocket holes. Top photo © 2015 by Rob McElroy.

Since the Capa Archive at ICP houses all those negatives and their contact sheets, both Whelan and Young have known this all along. Given the official position that first Whelan and now Young have occupied at ICP, they are de facto the world’s foremost authorities on Robert Capa. As such they represent, with regrettable accuracy, the deplorable condition of Capa scholarship in our time.

Cynthia Young, “Morning Joe,” MSNBC, 6–13–14, screenshot

The myth of Capa’s D-Day and the fate of his Omaha Beach negatives falls apart as soon as one compares its narrative to the military documentation of that epic battle. It collapses entirely when one examines closely the physical evidence — those photographs and their negatives.

The promulgation of that myth by the Capa Consortium, all of whose members have a vested financial and public-relations interest in furthering the myth, has proved itself calculated, systematic, duplicitous, and self-serving. Its voluntary dissemination by others, including reputable scholars and journalists, has shown those authors as lazy, careless, and professionally irresponsible. The Capa D-Day myth serves as a classic example of the genesis and evolution of a falsified version of history that, with its emphasis on the exploits of individual actors, distracts us from paying attention to the machinations of the corporate structures through which information must pass and get filtered before reaching the public — powerful institutions with agendas of their own.

I would like to think we have made a sufficiently convincing case that no one can credibly tell the standard Capa D-Day story again, at least not without acknowledging our contrary narrative. After all, our investigation forced a reluctant John Morris, the most energetic and vocal proponent of the legend, to recant its central components on Christiane Amanpour’s CNN show in the fall of 2014.

Most recently, in a Lensblog piece published in the New York Times on December 6, 2016 — just a day before his 100th birthday, and months before his death in Paris in July 2017 — Morris once again admitted that he’d never actually seen any heat-damaged 35mm negatives; that Capa may have only made the ten surviving images; and that he may have stayed on Omaha Beach only long enough to make them.

As for the institutions involved in perpetuating the myth: On June 6, 2016, ICP published this post on the institution’s Facebook page: “During the D-Day landing at Omaha beach, Robert Capa shot four rolls of 35mm film — only 11 frames survived. By accident, a darkroom worker in London ruined the majority of the film.” Since then, grudgingly, as a result of my public prodding, ICP has begun at last to make available to researchers the papers of Cornell Capa, promising to also permit access sometime in the near future to the papers of Richard Whelan, along with the Jozefa Stuart interviews from the early 1960s on which Whelan based much of his work.

Yet, as recently as October 2018, Cynthia Young published this statement in a special issue of the French newspaper Le Monde: “Capa, surrounded by explosions of bombs and bursts of machine guns, took photos in the water for a short while. … He expected his films to have been damaged by the water — he was squatting in the sea, troubled and agitated, tinged with blood. A few weeks later, he learned that all but ten images had been destroyed in the darkroom or during the shooting.” (My translation — A.D.C.).

Cynthia Young, “Les deux icônes de Capa,” Le Monde Hors-Série, 50 images qui ont marquél’histoire, October 2018, pp. 78–79

So there’s more work to be done on this subject. For the time being, our investigation has drawn to a close. In this country, though the Society of Professional Journalists honored our team with the 2014 Sigma Delta Chi Award for Research About Journalism, our work has received little attention, aside from a feature article in the official journal of the National Press Photographers Association, an article so rife with conflict of interest that the watchdog website iMediaEthics published a lengthy dissection of it. We have had better luck abroad; the project went viral in France in the summer of 2015, resulting in extensive coverage there in major periodicals and TV stations, as well as responses in Spain, Italy, the U.K., Brazil, and elsewhere.

Vincent Lavoie, L’Affaire Capa. Le procès d’une icône, 2017

I take heart from the fact that the two most recent books on Capa respond in different ways to our investigation. One, a graphic novel by Florent Silloray, published originally in France and now available in English, is (so far as I know) the only book on Capa of any kind to omit entirely the story of the darkroom disaster in London. The other, a meditation by French-Canadian Vincent Lavoie on the challenges to Capa’s 1937 “Falling Soldier” image, concludes with what its author and publisher must have felt was an obligatory commentary on our parallel research.

It took 70 years and the collaborative energies of powerful institutions and individuals to embed this fable in our cultural consciousness. Clearly, we still have much work to do if we hope to dislodge this fiction from the mythology of photojournalism and photo history — not to mention the larger D-Day myth into which it has become so thoroughly woven. But at least that process has begun — just in time for the 75th anniversary of D-Day, coming up in June 2019.

With minor revisions, this is the complete text of a lecture delivered on Friday, March 2, 2018 at the Society for Photographic Education 55th Annual Conference at the Marriott Hotel in Philadelphia, PA.) Its first English-language publication was in Exposure, the journal of the society.

About the author: A. D. Coleman has published 8 books and more than 2500 essays on photography and related subjects. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Formerly a columnist for the Village Voice, the New York Times, and the New York Observer, Coleman has contributed to ARTnews, Art On Paper, Technology Review, Juliet Art Magazine (Italy), European Photography (Germany), La Fotografia (Spain), and Art Today (China). His work has been translated into 21 languages and published in 31 countries. In 2002 he received the Culture Prize of the German Photographic Society, the first critic of photography ever so honored. In 2010 he received the J Dudley Johnston Award from the Royal Photographic Society (U.K.) for “sustained excellence in writing about photography.” In 2014 he received the Society for Photographic Education’s Insight Award for lifetime contribution to the field, and in 2015 the Society of Professional Journalists SDX Award for Research About Journalism. Coleman’s widely read blog “Photocritic International” appears at photocritic.com.

source https://petapixel.com/2019/02/16/debunking-the-myths-of-robert-capa-on-d-day/

0 notes

Text

Debunking the Myths of Robert Capa on D-Day

I want to give you a brief overview of an investigation that began almost five years ago, led by me but involving the efforts of photojournalist J. Ross Baughman, photo historian Rob McElroy, and ex-infantryman and amateur military historian Charles Herrick.

Our project, in a nutshell, dismantles the 74-year-old myth of Robert Capa’s actions on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and the subsequent fate of his negatives. If you have even a passing familiarity with the history of photojournalism, or simply an awareness of twentieth-century cultural history on both sides of the Atlantic, you’ve surely heard the story; it’s been repeated hundreds, possibly thousands of times:

Robert Capa landed on Omaha Beach with the first wave of assault troops at 0630 on the morning of June 6, 1944 (D-Day), on freelance assignment from LIFE magazine.

He stayed there for 90 minutes, until he either inexplicably ran out of film or his camera jammed.

During that time he made somewhere between 72 and 144 35mm b&w exposures of the Allied invasion of Normandy on Kodak Super-XX film.

Upon landing back in England the next day, he sent all his film via courier to assistant picture editor John Morris at LIFE’s London office, instead of delivering it in person.

This shipment included pre-invasion reportage of the troops boarding and crossing the English Channel, the just-mentioned coverage of the battle on Omaha Beach, and images of medics tending to the wounded on the return trip.

When the film finally arrived, around 9 p.m., the head of LIFE’s London darkroom, one “Braddy” Bradshaw, inexplicably assigned the task of developing these crucial four rolls of 35mm Omaha Beach images to one of the least experienced members of his staff, 15-year-old “darkroom lad” Denis Banks.

After successfully processing the 35mm films, in his haste to help Morris meet the looming deadline Banks absentmindedly closed the doors of the darkroom’s film-drying cabinet, which inexplicably were “normally kept open.” Inexplicably, nobody noticed that Banks had closed them.

As a result, after “just a few minutes,” that enclosed space with a small electric heating coil on its floor inexplicably became so drastically overheated that it melted the emulsion of Capa’s 35mm negatives.

Notified of this by the horrified Banks, Morris rushed to the darkroom, discovering that eleven of Capa’s negatives had survived, which he “saved” or “salvaged,” and which proved just sufficient enough to fulfill this crucial assignment to the satisfaction of LIFE’s New York editors.

That darkroom catastrophe blurred slightly the remaining negatives, “ironically” adding to their expressiveness. Furthermore, as a result of the overheating, the emulsion on those eleven negatives inexplicably slid a few millimeters sideways on their acetate backing, resulting in a visible intrusion of the film’s sprocket holes into the image area.

Robert Capa, D-Day images from Omaha Beach, contact sheet, screenshot from TIME video (May 29, 2014), annotated.

That standard narrative constitutes photojournalism’s most potent and durable myth. From it springs the image of the intrepid photojournalist as heroic loner, risking all to bear witness for humanity, yet at the mercy of corporate forces that, by cynical choice or sheer ineptitude, can in an instant erase from the historical record the only traces of a crucial passage in world events.

Jean-David Morvan and Séverine Tréfouël, “Omaha Beach on D-Day” (2015), cover

Moreover, it represents, arguably, the most widely familiar bit of folklore in the history of the medium of photography — one that appears not only in histories of photography and photojournalism, in biographies of and other books about Capa, but in novels, graphic novels, the autobiographies of such famous people as actress Ingrid Bergman and Hollywood director Sam Fuller, assorted films, and even in videos of Steven Spielberg talking about his inspirations for the opening scenes of his film Saving Private Ryan, not to mention countless retellings in the mass media.

Charles Christian Wertenbaker, “Invasion!” (1944), cover

An early version of this story started to circulate immediately after D-Day, made its first half-formed appearance in print in the fall of 1944, and received its full formal authorization with the publication of Capa’s heavily fictionalized memoir, Slightly Out of Focus, in the fall of 1947. Since then it’s been reiterated endlessly, either by John Morris or by others quoting or paraphrasing Capa’s or Morris’s version of the tale. It gets retold in the mass media with special frequency on every major celebration of D-Day — the 50th anniversary, the 60th, most recently the 70th. In short, it has gradually achieved the status of legend. That this legend went unexamined for seven decades serves as a measure of its appeal not just to photojournalists, to others involved professionally with photography, and to the medium’s growing audience, but to the general public.

For 70 years, despite the many glaring holes in it, no one questioned this story — least of all those in charge at the International Center of Photography, which houses the Capa Archive. These figures have included the late Cornell Capa, Robert’s younger brother and founder of ICP; the late Richard Whelan, Robert’s authorized biographer and the first curator of that archive; and Whelan’s successor in that curatorial role, Cynthia Young.

Ironically, two celebrations of the 70th anniversary of Capa’s D-Day images provoked our investigation. The first came as a flattering profile of John Morris, written by Marie Brenner for Vanity Fair magazine. Morris served as assistant picture editor in LIFE’s London bureau for that magazine’s D-Day coverage, and in this Brenner piece he recounts his version of the Capa-LIFE D-Day myth once more. Shortly thereafter, on May 29, 2014, TIME Inc. — the corporation that had commissioned and published Capa’s D-Day images back in 1944 — posted a video at its website celebrating those photographs, which some refer to as “the magnificent eleven.”

A division of Magnum Photos, the picture agency Capa founded with his colleagues in 1947 (the same year he published his memoir), produced that video for TIME. The International Center of Photography licensed the use of Capa’s images for that purpose. And none other than John Morris, by then 97 years old and living in Paris, provided the voice-over, his boilerplate narrative of those events. In short, this video involved the combined energies of the individual and institutional forces involved in the creation and propagation of this myth — what I came to define as the Capa Consortium.

The Capa Consortium, Keynote slide, © 2015 by A. D. Coleman

Assorted elements of those two virtually identical versions of the standard story, Brenner’s and Time Inc.’s, struck J. Ross Baughman as illogical and implausible. The youngest photojournalist ever to win a Pulitzer Prize (in 1978, at the age of 24), Baughman is an experienced combat photographer who has worked in war zones in the Middle East, El Salvador, Rhodesia, and elsewhere. As the founder of the picture agency Visions, which specialized in such work, he’s also an experienced picture editor. Ross contacted me to ask if I would publish his analysis at my blog, Photocritic International, as a Guest Post. I agreed.

In the editorial process of fact-checking and sourcing Baughman’s skeptical response to the standard narrative provided by Morris in that video, my own bulls**t detector began to sound the alarm. I realized that Baughman’s critique raised more questions than it answered, requiring much more research and writing than I could reasonably request from him. I decided to pursue those issues further myself.

This immersed me in the Capa literature for the first time. Speaking as a scholar, that came as a rude awakening. The most immediate shock hit as I read through a half-dozen print and web versions of Morris’s account of those events — in Brenner’s 2014 puff piece, in Morris’s 1998 memoir, and in various interviews, profiles, and articles — and watched at least as many online videos and films featuring Morris rehashing this tale. I realized that the only portion of this story that Morris claimed to have witnessed firsthand, the loss of Capa’s films in LIFE’s London darkroom, could not possibly have happened the way he said it did.

In retrospect, I cannot understand how so many people in the field, working photographers among them, accepted uncritically the unlikely, unprecedented story, concocted by Morris, of Capa’s 35mm Kodak Super-XX film emulsion melting in a film-drying cabinet on the night of June 7, 1944.

Anyone familiar with analog photographic materials and normal darkroom practice worldwide must consider this fabulation incredible on its face. Coil heaters in wooden film-drying cabinets circa 1944 did not ever produce high levels of heat; black & white film emulsions of that time did not melt even after brief exposure to high heat; and the doors of film-drying cabinets are normally kept closed, not open, since the primary function of such cabinets is to prevent dust from adhering to the sticky emulsion of wet film.

No one with darkroom experience could have come up with this notion; only someone entirely ignorant of photographic materials and processes — like Morris — could have imagined it. Embarrassingly, none of that set my own alarm bells ringing until I started to fact-check the article by Baughman that initiated this project, close to fifty years after I first read that fable in Capa’s memoir.

This is one of several big lies permeating the literature on Robert Capa. Certainly Capa knew it was untrue when he published it in his memoir; he had gotten his start in photography as a darkroom assistant in Simon Guttmann’s Dephot photo agency in Berlin. And Cornell Capa also knew that; he had cut his eyeteeth in the medium first by developing the films of his brother, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and David Seymour in Paris, then by working in the darkroom of the Pix photo agency in New York, then by moving on to fill the same role at LIFE magazine before becoming a photographer in his own right. My belated recognition of that fact led me to ask the obvious next question: If that didn’t happen to Capa’s 35mm D-Day films, what did? And if all these people were willing to lie about this, what were they covering up?

So, building on Baughman’s initial provocation, I began drafting my own extensions of what he’d initiated — and our investigation was launched.

In December of 2017 I published the 74th chapter of our research project. You’ll find all of it online at my blog; the easiest way to get to the Capa D-Day material is by using the url capadday.com. During these years I have become intimately familiar with a large chunk of what others have written and said about Capa and his D-Day coverage.

In my opinion, the bulk of the published writing and presentations in other formats (films, videos, exhibitions) devoted to the life and work of photojournalist Robert Capa qualifies as hagiography, not scholarship. Capa’s own account of his World War II experiences, Slightly Out of Focus, consistently proves itself inaccurate and unreliable, masking its sly self-aggrandizement with wry humor and self-deprecation. Morris’s memoir repeats Capa’s combat stories unquestioningly, adding to those his own dubious saga of the “ruined” negatives.

Richard Whelan, “This Is War! Robert Capa at Work” (2007), cover

Richard Whelan’s books, widely considered the key reference works on Capa, simply quote or paraphrase Capa and Morris uncritically, perhaps because they were sponsored, subsidized, published, and endorsed most prominently and extensively by the estate of Robert Capa and the Fund for Concerned Photography (both controlled by Capa’s younger brother Cornell) and the International Center of Photography, founded by Cornell, who also served as ICP’s first director.

Produced in most other cases under Cornell’s watchful eye or the supervision of one or another participant in the Capa Consortium, the remainder of the serious, scholarly literature on Robert Capa has almost all been subject to Cornell’s approval and reliant on either the problematic principal reference works or on Robert Capa materials stored in Cornell’s private home in Manhattan, with access dependent on his consent. Consequently, it constitutes an inherently limited corpus of contaminated research, fatally corrupted by its unswerving allegiance to both its patron and its patron saint. Such bespoke scholarship becomes automatically suspect.

Cornell Capa, interview with Barbaralee Diamonstein, 1980, screenshot

The second failing of this heap of compromised materials resides in its reliance on untrustworthy and far from neutral sources: Robert Capa, with a demonstrated penchant for self-mythification; his younger brother Cornell, a classic “art widower” with every reason to enhance his brother’s reputation; and Robert’s close friend and Cornell’s, John Morris, whose own stature in the field premises itself on the Capa D-Day legend. Only Alex Kershaw’s unauthorized Capa biography, Blood and Champagne, published in 2002, maintains its independence from Cornell’s influence, but at the cost of losing access to the primary research materials and consequently reiterating the erroneous information in the accounts of Capa, Morris, and Whelan. Virtually everything else published about Capa, including those stories in the mass media that appear predictably every five years along with celebrations of D-Day, unquestioningly presents the prevailing myth.

This Capa literature suffers from a third fundamental flaw: Those generating it (with the exception of Capa himself and his brother Cornell), have no direct, hands-on knowledge of photographic production, no military background (significant in that Robert Capa’s most important work falls under the heading of combat photography), and no forensic skills pertinent to the analysis of photographic materials. Nor were they encouraged by their patron, Cornell Capa, to make up for those deficiencies by involving others with those competencies in their projects. Instead, their privileged relationship to the primary materials, along with the availability of a prominent and well-funded platform at ICP, enabled them to effectively invent whatever suited them, pleased their benefactor, and served their purposes.

Responsible Capa scholarship, therefore, must begin by distrusting the extant literature, turning instead to the photographs themselves and relevant documents that the Capa estate and ICP do not control and to which they therefore cannot prohibit access. Those materials lie at the core of our research project.

Here’s a short summary of what we’ve found:

Capa sailed across the English Channel on the U.S.S. Samuel Chase.

According to the official history of the U.S. Coast Guard, fifteen waves of LCVPs (commonly called Higgins boats) carrying troops left the U.S.S. Samuel Chase for Omaha Beach that morning. Capa almost certainly rode in with Col. Taylor and his staff, the command group of Company E of the 16th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 1st Division, to which Capa had been assigned. They constituted part of the thirteenth wave.

That wave arrived at the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach at 8:15, a half hour after the last of the 16th Infantry Regiment’s nine rifle companies. We can see from Capa’s images that numerous waves of troops preceded them.

Using distinctive landmarks visible in Capa’s photos, Charles Herrick has pinpointed exactly where Capa landed on Easy Red: the beach at Colleville-sur-Mer. Gap Assault Team 10 had charge of the obstacles in that sector. An existing exit off this sector made it possible to reach the top of the bluffs with relative ease. Col. Taylor would become famous for announcing to the hesitant troops he found there, “Two kinds of people are staying on this beach, the dead and those who are going to die — now let’s get the hell out of here,” and urging them up the Colleville-sur-Mer draw to the bluffs.

Robert Capa, CS frame 4, neg. 32, detail, annotated

Fortuitously, that stretch of Easy Red represented a seam in the German defenses, a weak point at the far end of the effective range of two widely separated German blockhouses. Both cannon fire and small-arms fire there proved relatively light — one reason for the success of Gap Assault Team 10 in clearing obstacles in that area. This explains why, contrary to LIFE’s captions and Capa’s later narrative, his images show no carnage, no floating bodies and body parts, no discarded equipment, and no bullet or shell splashes. This also explains why the Allies broke through early at that very point.

Capa did not run out of film, nor did his camera jam, nor did seawater damage either his cameras or his film. In his memoir, Capa first implies that he exposed at most two full rolls of 35mm film — one roll in each of his two Contax II rangefinder cameras, 72 frames in all — at Omaha Beach. By the end of that chapter, this has somehow grown to “one hundred and six pictures in all, [of which] only eight were salvaged.” John Morris claims he received 4 rolls of Omaha Beach negatives from Capa. We find no reason to believe that Capa made more than the ten 35mm images of which we have physical evidence.

Capa made the first five of those images while standing for almost two minutes on the ramp of the landing craft that brought him there. In them we see Capa’s traveling companions carrying not small-arms assault weapons but bulky oilskin-wrapped bundles, most likely radios and other supplies for the command post they meant to establish.

Capa made his sixth exposure from behind a mined iron “hedgehog,” one of many such obstacles protecting what Nazi Gen. Erwin Rommel called the “Atlantic Wall.” He made his last four exposures — including “The Face in the Surf” — from behind Armored Assault Vehicle 10, which was sitting in the surf shelling the gun emplacements on the bluffs.