#clevosaurus

Text

The World of Dinosaurs. Written by L. B. Halstead. 1979.

Internet Archive

#prehistoric#prehistoric reptiles#kuehneosaurus#clevosaurus#synapsids#therapsids#cynodonts#morganucodon

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Archovember Day 9 - Dynamosuchus collisensis

The Triassic was a very productive time for pseudosuchians. They were trying out every shape, size, and niche while dinosaurs were only just beginning to get a foothold. The Ornithosuchids were a family of these Triassic pseudosuchians. They had downturned snouts and were facultatively bipedal, meaning they spent most of their time walking on all fours but could walk on their hind legs for short periods of time. In Late Triassic Brazil, Ornithosuchids were represented by the high-walking, bone-crushing scavenger Dynamosuchus collisensis.

Dynamosuchus had a powerful bite force but a slow bite speed, meaning it was likely a scavenger. Considered a close relative of the Argentinian Venaticosuchus, Dynamosuchus filled the important niche of large scavenger in the Santa Maria Formation.

Dynamosuchus would have lived alongside cynodonts like Trucidocynodon and Exaeretodon, rhynchocephalians like Clevosaurus, proterochampsids like Stenoscelida, as well as the basal sauropodomorphs Bagualosaurus and Pampadromaeus, and probably fed from their carcasses as well.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Dynamosuchus collisensis#Dynamosuchus#Ornithosuchids#pseudosuchians#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2023

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

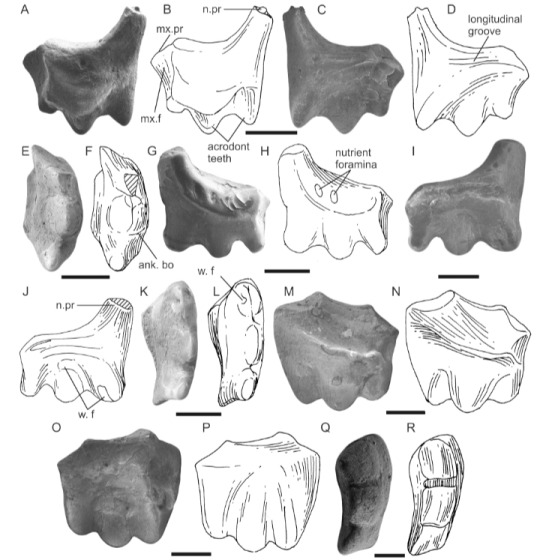

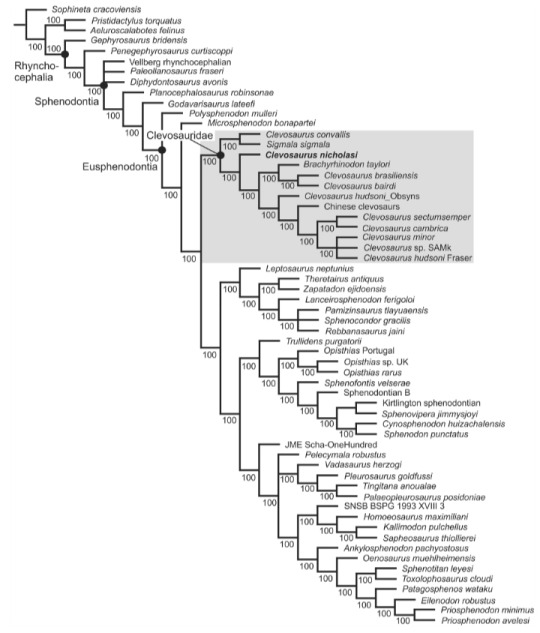

A new clevosaurid (Lepidosauria: Rhynchocephalia) from the Upper Triassic of India

Published 3rd August 2023

A new clevosaurid, Clevosaurus nicholasi, from the Upper Triassic Tiki Formation in India is described based on partial material.

Clevosaurus nicholasi partial premaxilae

Clevosaurus nicholasi middle portions of manidbular

phylogenetic anaylsis of Clevosaurus nicholasi

Artist reconstruction of Clevosaurus hadroprodon, a different species of clevosaurid, by Jorge Blanco. from

Source:

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A specimen retrieved from a cupboard in the Natural History Museum in London has shown that modern lizards originated in the Late Triassic and not the Middle Jurassic as previously thought.

This fossilized relative of living lizards such as monitor lizards, gila monsters. The specimen was simply labeled 'Clevosaurus.

There is only one major primitive feature not found in modern squamates, an opening on one side of the end of the upper arm bone, the humerus, where an artery and nerve pass through

Cryptovaranoides does have some other, apparently primitive characters such as a few rows of teeth on the bones of the roof of the mouth, but experts have observed the same in the living European Glass lizard and many snakes such as Boas and Pythons have multiple rows of large teeth in the same area. Despite this, it is advanced like most living lizards in its braincase and the bone connections in the skull suggest that it was flexible.

0 notes

Photo

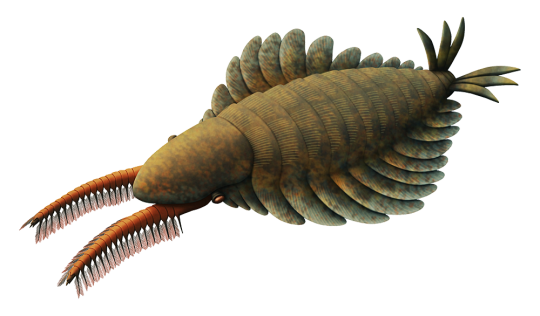

Time for some more PBS Eons commission work!

The radiodonts Lyrarapax and Tamisiocaris, from "How Plankton Created A Bizarre Giant of the Seas"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G0oKBPZODhM

The rhynchocephalians Sphenotitan, Clevosaurus, and Kawasphenodon, from "When Lizards Took Over the World"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=peeX3PKOE_w

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#pbs eons#lyrarapax#tamisiocaris#radiodonta#dinocaridida#arthropod#invertebrate#spenotitan#clevosaurus#kawasphenodon#sphenodontia#rhynchocephalia#lepidosauria#reptile#art

1K notes

·

View notes

Link

My paper is officially official and to mark that, it’s currently available to read online for free for the next fifty days!

Clevosaurus cambrica says to go check out her systematic description.

#honestly a gripping read#this is like the only worthwhile thing I've done in my life#palaeontology#paleontology#clevosaurus#fossil#dinosaur#crocodile#crocodylomorph#trust me these are relevant tags#you'll have to read the paper#archosaur#Sphenodon#sphenodont#tuatara#wales#bristol#university#University of Bristol#bristol university

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kuehneosaurus latus

By Tyler Young

Etymology: Kuhne’s Reptile

First Described By: Robinson, 1962

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Lepidosauromorpha?, Kuehneosauridae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 216 and 202 million years ago, from the end of the Norian through the Rhaetian ages of the Late Triassic

Kuehneosaurus is known from the Steinmergel Group in Luxembourg, the Cromhall Quarry in Gloucestershire, and the Panty-y-ffynnon Quarry of Wales.

Physical Description: Kuehneosaurus is a true weirdo, alright - a small, lizard-like reptile, you almost can squint and pretend its normal until you notice the expanding ribs on the side of the creature - and you realize that Kuehneosaurus is not normal in the slightest. While gliding lizards are not something we’re totally unfamiliar with - the genus Draco, today, for example - Kuehneosaurus and its relatives took it to new heights by being huge. Insanely huge. Kuehneosaurus was probably around 72 centimeters long, as opposed to the modern Draco which is closer to 20 centimeters in body length. Kuehneosaurus had a large body, with long limbs and a small head, and a ridiculously long tail. However, its wings - for lack of a better word - were much smaller than those of its close relative Kuehneosuchus; instead of jutting out by up to 30 centimeters, they only went out as many as 15 centimeters from the body. As a non-Avemetatarsalian reptile, it would have been covered in scales, probably similar to those of Lepidosaurs, though that is just conjecture.

Diet: Based on its size and other early Lepidosauromorphs of the time - and the modern gliding lizards - Kuehneosaurus was probably an insectivore, using small pointed teeth to catch insects in its mouth.

Behavior: Because of its small wings, Kuehneosaurus would not have been able to glide. However, it would have been able to parachute down from the trees in its environment with extensive agility and control. It would have been able to descend at a 45 degree angle, going between 10 and 12 meters per second down toward the ground. It could also control the angle and pitch of the wings by moving flaps of skin attached to the back of the throat. Since it lived alongside other gliding reptiles, this made the environment of Kuehneosaurus filled with little lizard-esque reptiles falling with style all over the forest. Given its common nature, it probably lived in loose social groups; whether or not it showed more complex social behavior, including parental care, is unknown but more unlikely than not. It would have most likely been cold blooded as well, making it more sluggish than other airborne creatures of the time (ie, the flighted Ornithodirans). It’s also possible that those wings would have been colorful, and used for display, though this is somewhat conjecture.

Ecosystem: Kuehneosaurus lived in the dense, dry forests of northern Pangea at the tail end of the Triassic period. Obviously, it took clear advantage of these forests, dropping down from tree to tree in search of food. It wasn’t alone here, to be sure - in fact, during its tenure, it shared its time with many other Triassic oddities. In Luxembourg, it shared its environment with some sharks and fish from the nearby sea - including Perleidus, Saurichthys and Rhomphaiodon - as well as freshwater lungfish like Ceratodus. Temnospondyls featured Plagiosaurus and Cyclotosaurus. Synapsids were present too, including a Morganucodont and the Therapsid Pseudotriconodon. As for other reptiles, there was the Tuatara Clevosaurus, the pterosaur Eudimorphodon, and other mystery creatures. In England, it lived with the Trilophosaurid Variodens, Clevosaurus once more as well as the other Tuataras Sigmalam Diphydontosaurus, Pelcymala and Planocephalus, as well as potential mammals, the suchian Terrestrisuchus, and potential Drepanosaurs and Pterosaurs. And in Wales, it lived alongside Diphydontosaurus and Clevosaurus again, as well as Aenigmaspina and the dinosaur Pantydraco. In short, it was surrounded by a variety of other animals - and may have even used its fancy falling to escape from pterosaurs in its forest.

Other: What is Kuehneosaurus? For a while, it has seemed that Kuehneosaurus and its relatives were Lepidosauromorphs - relatives of modern lizards, snakes, and tuatara. This was important, because the ancient relatives of archosaurs - the Archosauromorphs - make up the vast majority of Triassic weirdos and were extremely diverse throughout the Triassic period. One could even call the Triassic the golden age of these animals. However, Lepidosauromorphs are a lot less weird - by and large - and a lot less diverse until you get to ones that are noticeably like living members (ie, there were a lot of Triassic Tuatara - but they were Tuatara, not weird offshoots). Kuehneosaurus and its gliding relatives were really the most distinctive Weird Lepidosauromorph Experiments from the period.

And… they might be Archosauromorphs after all. Recent studies of these animals have indicated they might be Archosauromorphs, just another tally in the great list of weird little crocodile/dinosaur/pterosaur cousins. While this is preliminary, it does indicate - what the heck were Lepidosauromorphs even doing? We may never know, but the fun adventures of Kuehenosaurus remain with us.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Benton, M. J. 1985. Classification and phylogeny of the diapsid reptiles. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 84(2):97-164.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698.

Delsate, D. 1999. Reptiles terrestres (Lepidosauromorpha et Traversodontidae) du Trias superieur de Medernach (G.-D. de Luxembourg) [Terrestrial reptiles (Lepidosauromorpha and Traversodontidae) from the Upper Triassic of Medernach (G. D. of Luxembourg)]. Travaux Scientifiques du Musee d'Histoire Naturelle de Luxembourg 32:55-86.

Duffin, C. J. 1993. Mesozoic chondrichthyan faunas 1. Middle Norian (Upper Triassic) of Luxembourg. Palaeontographica Abteilung A 229:15-36.

Estes, R. 1983. Sauria terrestria, Amphisbaenia. Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie 10A:1-249.

Evans, S. C. 2003. At the feet of the dinosaurs: the early history and radiation of lizards. Biological Reviews 78: 513 - 551.

Evans, S. E. 2009. An early kuehneosaurid reptile (Reptilia: Diapsida) from the Early Triassic of Poland. Paleontologica Polonica 65: 145 - 178.

Evans, S. E., M. Borsuk-Bialynicka. 2009. A small lepidosauromorph reptile from the Early Triassic of Poland. Palaeontologica Polonica 65: 179 - 202.

Evans, S. E., Jones M. E. H. 2010. The Origin, early history and diversification of lepidosauromorph reptiles. New Aspects of Mesozoic Biodiversity, 27 Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences 132: 27 - 44.

Fraser, N. C., and G.M. Walkden. 1983. The ecology of a Late Triassic reptile assemblage from Gloucestershire, England. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 42:341-365.

Godefroit, P., and D. Sigogneau-Russell. 1995. Cynodontes et mammifères primitifs du Trias Supèrieur, en region Lorraine et Luxembourgeoise [Cynodonts and primitive mammals form the Upper Triassic, in the Lorraine region and Luxembourg]. Bulletin de la Société Belge de Géologie 104(1-2):9-21.

Hahn, G., J. C. Lepage, and G. Wouters. 1984. Cynodontier-Zähne aus der Ober-Trias von Medernach, Grossherzogtum Luxemburg [Cynodontian teeth from the Upper Triassic of Medernach, Grand Duchy of Luxembourg]. Bulletin de la Société Belge de Géologie 93(4):357-373.

Keeble, E., D. I. Whiteside, and M. J. Benton. 2018. The terrestrial fauna of the Late Triassic Pant-y-ffynnon Quarry fissures, South Wales, UK and a new species of Clevosaurus (Lepidosauria: Rhynchocephalia). Proceedings of the Geologists' Association.

Kermack, K. A. 1953. An ancestral crocodile from south Wales. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London 166(1–2):1-2.

Kuhn, O. W. M. 1966. Die Reptilien. System und Stammesgeschichte [The Reptiles. Systematics and Phylogeny.] 1-154.

Pritchard, A. C., S. J. Nesbitt. 2017. A bird-like skull in a Triassic diapsid reptile increases heterogeneity of the morphological and phylogenetic radiation of Diapsida. Royal Society Open Science 4 (10): 170499.

Robinson, P. L. 1962. Gliding lizards from the Upper Keuper of Great Britain. Proceedings of the Geological Society of London 1601: 137 - 146.

Robinson, P. L. 1967. Triassic vertebrates from Upland and Lowland. Science and Culture 33: 169 - 173.

Schoch, R. R., and A. R. Milner. 2014. Handbook of Paleoherpetology Part 3A2 Temnospondyli I.

Stein, K. C. Palmer, P. G. Gill, M. J. Benton. The aerodynamics of the British Late Triassic Kuehneosauridae. Palaeontology 51 (4): 967 - 981.

#kuehneosaurus#kuehneosaurus latus#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#reptile#prehistoric life#paleontology

238 notes

·

View notes

Text

A new sphenodontian from Brazil is the oldest record of the group in Gondwana

Research published this Wednesday (August 14th) in Scientific Reports describes Clevosaurus hadroprodon, a new reptile species from Rio Grande do Sul state in southern Brazil. Its fossils remains—jaws and associated skull bones—were collected from Triassic rocks (c. 237-228 million-years old) making it the oldest known fossil of its kind in Gondwana, the southern supercontinent that would eventually become Africa, Antarctica, Australia, India, and South America.

"Clevosaurus hadroprodon is an important discovery because it combines a relatively primitive sphenodontian-type tooth row with the presence of massive tusk-like teeth that were possibly not for feeding, but rather used for mate competition or defense. If correct, this means that non-feeding dental specializations predated changes in the sphenodontian dentition related to feeding strategies. This is a very exciting discovery." says co-author Randall Nydam, Professor at Midwestern University (US).

In addition to its unique dentition, the authors stress that Clevosaurus hadroprodon also adds to the growing evidence that the early diversification of sphenodontians occurred in the widely separated regions of Gondwana destined to become South American and India. This illustrates the importance of the role of the Gondwanan lepidosaur fauna in our growing understanding of the earliest stages of sphenodontian evolution and the global biogeographic distribution of lepidosaurs.

Continue reading.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sulle antiche isole del Regno Unito prosperavano rettili che sgranocchiavano insetti

Sulle antiche isole del Regno Unito prosperavano rettili che sgranocchiavano insetti

Due specie di rettili simili a lucertole Clevosaurus che cacciano le loro prede preferite: Clevosaurus hudsoni che si nutre di un coleottero croccante (in alto) e Clevosaurus cambrica (in basso) che si nutre di un insetto più morbido.

Analizzando la meccanica delle mascelle fossilizzate dei rettili che vivevano nella regione del Canale di Severn nel Regno Unito 200 milioni di anni fa, i…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Note

what other species was named after him?

Clevosaurus sectumsemper an ancient reptile. i think there’s a third one that i can’t remember properly

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

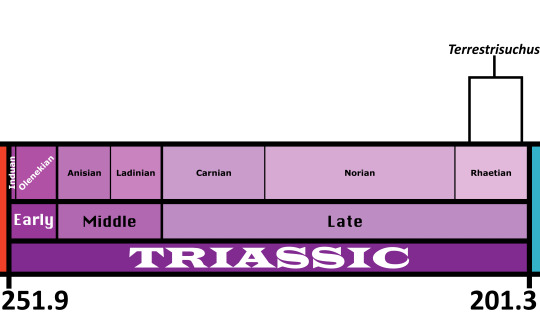

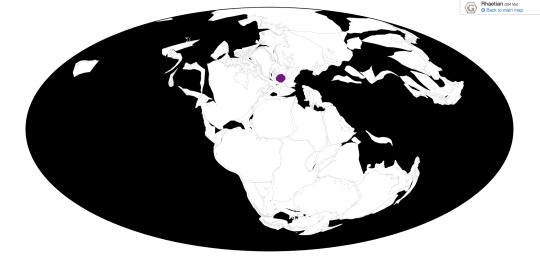

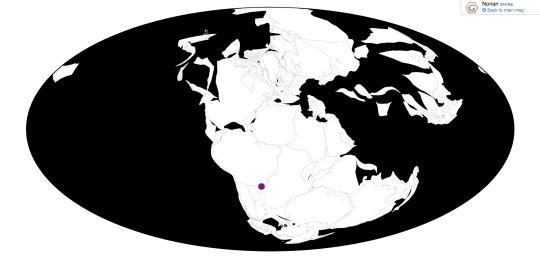

Terrestrisuchus gracilis

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Land Crocodile

First Described By: Crush, 1984

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha, Crocopoda, Archosauriformes, Eucrocopoda, Crurotarsi, Archosauria, Pseudosuchia, Suchia, Paracrocodylomorpha, Loricata Crocodylomorpha

Time and Place: Sometime around 205 to 203 million years ago, in the Rhaetian of the Late Triassic.

Terrestrisuchus is known from the Cromhall Quarry of England and the Pant-y-ffynnon Quarry of Wales

Physical Description: Terrestrisuchus was a fascinating early Crocodile relative, hailing from the Latest Triassic of the British Isles. Fascinating, in that, the closest relatives to proper Crocodiles we have from the Triassic are not the crocodile-esque Phytosaurs, nor the large land predator Rausichians, but these strange fast-moving reptiles from the end of the period. Looking weirdly like early dinosaur relatives, but crocodile-like, they were the most derived Pseudosuchians found in the Triassic and the earliest known Crocodylomorphs, the group of Pseudosuchians that would make it into the Jurassic and dominate the rest of the Mesozoic Era. Terrestrisuchus was nothing like a modern Crocodile in external appearance - small and thin, with a long flexible tail and long legs directly underneath its body. It was around 1 meter long, and only would have weighed up to 15 kilograms. It had a long, narrow head as well. It also had hindlimbs much longer than its forelimbs. They also ran on their toes, another trait that Terrestrisuchus shared with dinosaurs. That said, unlike dinosaurs, it would have been covered in tough scales - though what sorts, we can’t be sure, as skin impressions of Terrestrisuchus are not known.

Diet: Terrestrisuchus had small, needle-like teeth, indicating it was most likely insectivorous.

Behavior: Terrestrisuchus was, more likely than not, warm-blooded - making it a very quick and agile animal. The proportions of its front legs heavily indicates that it would have been able to run bipedally, allowing it to be even more agile and able to run after quick insects flying above its head. Terrestrisuchus running on its toes was even more helpful to this end, and its long tail would have served as a good counterbalance against the front-heaviness of its head and arms. Still, it probably couldn’t have used its hands for grabbing - at least, not as well as distant dinosaur cousins. The long snout of Terrestrisuchus would have been able to snap shut around a fast moving insects, helping to trap it quickly while on the move. It probably would have been able to gallop, at least somewhat, and thus could catch even faster insects in its environment. As an archosaur, it most likely would have taken care of its young, though the extent of this care is unknown.

Ecosystem: During the Triassic, Wales was an island in the tropical archipelago that was Europe. This island was occasionally hit by storms and was dotted by caves, which ended up being where the fossils were preserved. Terrestrisuchus lived alongside dinosaurs such as Pantydraco, the pseudosuchian Aenigmaspina, rhynchocephalians such as Clevosaurus and Diphydontosaurus, procolophonids, and the weird gliding Kuehneosaurus.

Other: Despite what you may read floating around online, it is not widely accepted that Terrestrisuchus is a juvenile of Saltoposuchus. The suggestion has only been made in a conference poster from 2003, and the two genera are separated both temporally and geographically.

Also shoutout to @deinonychusfloof because she studies Pant-y-ffynnon fauna!

~ By Meig Dickson and Henry Thomas

Sources Under the Cut

Benson, R. B. J., S. Brussatte. 2012. Prehistoric Life. London: Dorling Kindersley. 216.

Bronzati, M., F. C. Montefeltro, M. C. Langer. 2012. A species-level supertree of Crocodyliformes. Historical Biology 24 (6): 598 - 606.

Crush, P. J. 1984. A Late Upper Triassic Sphenosuchid Crocodilian from Wales. Palaeontology 27 (1): 131 - 157.

Fiorelli, L., J. O. Calvo. 2008. New remains of Notosuchus terrestris Woodward, 1896 (Crocodyliformes: Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Late Cretaceous of Neuquen, Patagonia, Argentina. Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro 66 (1): 83 - 124.

Irmis, R. B., S. J. Nesbitt, H.-D. Sues. 2014. Early Crocodylomorpha. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 379: 275 - 302.

Emily Keeble, pers. comm.

Keeble, E., Whiteside, D.I., Benton, M.J. 2018. The terrestrial fauna of the Late Triassic Pant-y-ffynnon Quarry fissures, South Wales, UK and a new species of Clevosaurus (Lepidosauria: Rhynchocephalia). Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 129(2): 99-119.

Nesbitt, S. J. 2011. The early evolution of archosaurs: relationships and the origin of major clades. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 352: 1 - 292.

Palmer, D., ed. 1999. The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. 98.

Sertich, J. J. W., P. M. O’Connor. 2014. A new crocodyliform from the middle Cretaceous Galula Formation, southwestern Tanzania. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24 (2): 576 - 596.

#terrestrisuchus#terrestrisuchus gracilis#sphenosuchian#pseudosuchian#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#prehistoric life#paleontology

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brasilodon

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Brazilian tooth

First Described By: Bonaparte et al., 2003

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota, Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Synapsida, Eupelycosauria, Metopophora, Haptodontiformes, Sphenacomorpha, Sphenacodontia, Pantherapsida, Sphenacodontoidea, Therapsida, Eutherapsida, Neotherapsida, Cynodontia, Epicynodontia, Eucynodontia, Probainognathia, Chiniquodontoidea, Prozostrodontia, Brasilodontidae

Referred Species: B. tetragonus, B. quadrangularis

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 227 to 208 million years ago, in the Norian of the Late Triassic.

Take a guess where a synapsid whose name is “Brazilian tooth” was found.

Physical Description: Brasilodon would have looked like a pretty average cynodont in life, because it was. Brasilodon’s skull was wider than deep, as was the case with many cynodonts. Its teeth were distinguished into incisors, canines, and molars. The teeth were small, and the incisors were pointy. The molars were taking on the multicusped shape that modern mammals have, unlike more basal synapsids (which had simple pointy cheek teeth).The teeth were replaced in a polyphyodont manner, where the teeth can theoretically be replaced throughout the animal’s life (unlike most mammals, which get one tooth replacement, and that’s it). Brasilodon’s inner ears indicate a degree of hearing ability close to those of modern mammals, but it lacked the tympanic bone (one of the mammalian ear bones). The rest of the body would have looked rather badgery, with semi-sprawling limbs. Many anatomical details of the postcrania are more similar to those of mammals than other cynodonts. Brasilodon was small, at around 12 cm long, and would have probably been very cute.

Diet: Brasilodon was probably a carnivore. Due to its small size and small, pointy teeth, it may have eaten insects, but its jaw was more resistant to stress than other probainognathians, hinting it may have also taken larger prey.

Behavior: Brasilodon probably had a generalized, adaptable lifestyle. Its forelimbs indicate powerful retractor muscles, but don’t have the same level of robusticity as many burrowing mammals. There are also features of the humerus in common with opossums and primates, and the limbs show a greater degree of flexibility than other probainognathians, which could hint that Brasilodon may have been able to climb. Or… they could just mean nothing; at this size, these adaptations may have been simply to get over irregular, rocky terrain. Nevertheless, burrowing and climbing are both ways to escape potential predators, and climbing could have put Brasilodon in closer proximity to tasty insects.

Ecosystem: Brasilodon was found in the Caturrita Formation of Brazil. In the Triassic, the region was probably fairly arid, with lazy rivers flowing through. There was enough water to support the growth of conifers, at least. This environment was also the home of other cynodonts, such as Brasilitherium, Irajatherium, Minicynodon, and Riograndia, the latter of which was more adapted for burrowing than Brasilodon. Also in this environment lived the sauropodomorph Guaibasaurus, the enigmatic lepidosaur Cargninia, the rhynchocephalian Clevosaurus, and beetles. There was also Faxinalipterus, which was originally described as an early pterosaur, but is probably just some random small reptile.

Other: Brazilodon is one of the very closest relatives of Mammaliaformes (the clade that includes mammals and the very mammaliest synapsids, like Adelobasileus, Morganucodon, and docodonts). Although it has many mammal-like traits, it just wasn’t quite there yet.

~ By Henry Thomas

Sources under the cut

Bonaparte, J.F., Martinelli, A.G., Schultz, C.L. 2005. On the sister-group of mammals: Brasilodon and Brasilitherium (Cynodontia, Probainognathia) from the late Triassic of southern Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia 8(1): 25-46.

Guignard, M.L., Martinelli, A.G., Soares, M.B. 2019. The postcranial anatomy of Brasilodon quadrangularis and the acquisition of mammaliaform traits among non-mammaliaform cynodonts. PLoS ONE 14(5): e0216672.

Martinelli, A.G., Bonaparte, J.F. 2010. Postcanine replacement in Brasilodon and Brasilitherium (Cynodontia, Probainognathia) and its bearing in cynodont evolution. In: Calvo, J., Poriri, J., Gonzalez Riga, B., Dos Santos, D. eds. Paleontologia y dinsoaurios desde America Latina. Pp. 179-186.

Salcido, C.J., Rayfield, E.J., Gill, P., Soares, M.B., Martinelli, A.G. 2018. Skull mechanics and functional morpholoy of Brasilodontidae, the sister clade to mammals. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Annual Meeting, Albuquerque.

Tatarinov, L.P. 2010. On the Origin of the Tympanic Membrane: the Middle Ear of Mammals. Paleontological Journal 44(1): 92-94.

#brasilodon#brasilodontid#probainognathian#cynodont#synapsid#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#prehistoric life#paleontology

152 notes

·

View notes

Text

Diphydontosaurus avonis

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Reptile with two types of teeth

First Described By: Whiteside, 1986

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Lepidosauromorpha, Lepidosauria, Rhynchocephalia, Sphenodontia

Referred Species: D. avonis

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 227 to 200 million years ago, from the Norian to Rhaetian of the Late Triassic

Diphydontosaurus is known from Southern England and Wales, and possibly also from Northern Italy.

Physical Description: Diphydontosaurus is an early-derived relative of the tuatara, one of the oldest in fact. Like the tuatara, it resembles a lizard in appearance, probably even more so than living tuataras. It was also very small too. Like, really small. 10 centimetres long from head-to-tail with a skull less than 15 millimetres long, small. The skull itself has massive eyes and a pretty short snout, so it was probably a rather cute looking little reptile. The most distinctive features of Diphydontosaurus are its jaws and teeth. Living tuataras have their teeth fused to the jaw bones (acrodont), which wear down and can’t be replaced. Diphyodontosaurus has these teeth at the back of its jaws, but the teeth in front were attached in sockets (pleurodont), like some lizards. These teeth were sharp and peg-like, perfect for puncturing the carapaces of insects, while the teeth at the back formed a shear for slicing through them. Diphydontosaurus also lacked the characteristic “beak” at the tip of the jaws found in later sphenodonts, and probably didn’t chew its food the way modern tuataras can (yes, tuataras can chew). Diphydontosaurus would also have had a typmanum, a.k.a. an eardrum, visible at the back of its head, again like most lizards but unlike the living tuatara.

Diet: Diphydontosaurus was insectivorous, as evidenced by its small size and teeth, although like some living insular lizards it may have eaten plants to supplement its diet.

Behavior: Diphydontosaurus was likely an active predator or insects and other small arthropods. Its large eyes and well developed ear openings indicate that it likely relied heavily on these senses for hunting and catching prey. They may have especially congregated around the abundant fissures and sinkholes in their habitat, where moist soils and plants would have attracted plenty of insects and other arthropods, and so too the Diphydontosaurus. Being small would have been handy for clambering over steep rock faces after prey, out of reach of other, larger reptiles.

Ecosystem: Diphydontosaurus was part of a diverse collection of island ecosystem in the latest Triassic of Europe, populating low-lying islands of limestone pockmarked with deep fissures and caves eroded into the karst. The species found on each island differed, but there was some broad similarities. The largest land animals on these islands were the possibly dwarfed prosauropod dinosaurs Thecodontosaurus and Pantydraco, as well as small theropods. Pseudosuchian archosaurs were here too, including the small predator Terrestrisuchus and the enigmatic Aenigmaspina, both extremely long-legged, agile animals well suited for navigating the karst-riddled landscape. There was also a drepanosaur around, as well as the gliding reptiles Kuehneosaurus and Kuehneosuchus whose affinities remain mysterious. They could be lepidosaurs like sphenodonts, or, they may belong to the strange allokotosaurs on the archosaur side of the tree! The jury is still out on them. Some of the islands also hosted small mammaliaforms, including Morganucodon and Eozostrodon.

Stem-tuataras like Diphydontosaurus were remarkably diverse, and it coexisted with numerous other genera such as Gephyrosaurus, Clevosaurus, and Planocephalosaurus, each with multiple species, and there are still more new types of sphenodont to be described! Such a high density of different sphenodonts on these islands implies they were all specialised for different ways of life. Diphydontosaurus was one of the most abundant of all sphenodonts on the islands of Late Triassic Europe, no doubt thanks to its small size and insectivorous diet. However, this small size left it vulnerable, and it may have been preyed upon by its larger, more predatory cousins like Clevosaurus.

Other: Diphydontosaurus is one of the oldest known, and is the earliest diverging, sphenodont, the group of animals that includes living tuataras but excludes the even earlier-diverging rhyncocephalians, the gephyrosaurids (the distinction isn’t huge, mostly that gephyrosaurids have completely pleurodont teeth). The anatomy of Diphydontosaurus was unexpected compared to modern tuataras, which are so often described as ‘living fossils’ unchanged since the Mesozoic. In fact, certain features of Diphydontosaurus and other early sphenodonts reveal that the modern tuatara is actually pretty derived compared to its ancestors, especially so in the skull, including the loss of its external ears, its shearing teeth and the ability to chew food. Diphydontosaurus really just goes to show you can’t judge a 200 million year old clade by its sole extant member, eh?

~ By Scott Reid

Sources under the Cut

Whiteside D.I. (1986). "The head skeleton of the Rhaetian sphenodontid Diphydontosaurus avonis gen. et sp. nov., and the modernising of a living fossil". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 312 (1156): 379–430.

Whiteside, D.I., Duffin, C.J., Gill, P.G., Marshall, J.E.A., Benton, M.J. (2016). “The Late Triassic and Early Jurassic fissure faunas from Bristol and South Wales: stratigraphy and setting”. Palaeontologia Polonica 67, 257–287.

David I. Whiteside, Christopher J. Duffin, (2017). "Late Triassic terrestrial microvertebrates from Charles Moore's "Microlestes" quarry, Holwell, Somerset, UK". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 179 (3): 677–705.

Whiteside, D.I., Marshall, J.E.A. (2008). "The age, fauna and palaeoenvironment of the Late Triassic fissure deposits of Tytherington, South Gloucestershire, UK". Geological Magazine. 145 (1): 105–147.

#Diphydontosaurus#Diphydontosaurus avonis#Sphenodont#Tuatara#Reptile#Prehistoric Life#Palaeoblr#Paleontology#Prehistory#Triassic#Triassic Madness#Triass March Madness

217 notes

·

View notes