#dinocaridida

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#paleontology#new species#a tiny mothra#mosura fentoni#hurdiidae#radiodont#dinocaridida#arthropod#stem-arthropod#excellent names

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

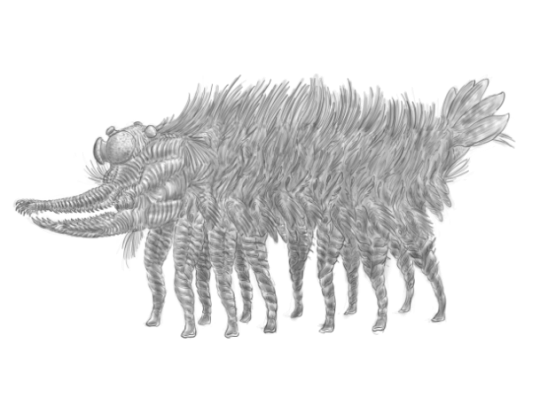

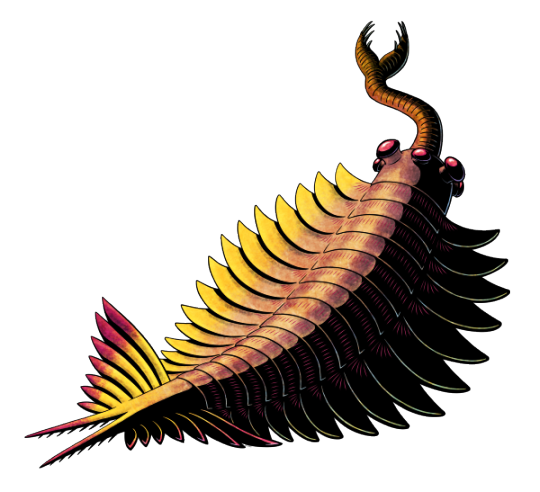

Bonecracker (artwork by Yuujinner)

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Arthropoda

Class: Dinocaridida

Order: Rastrodontida

Family: Tanygnathidae

Genus: Tanygnathus

Species: T. pentops (“five-eyed long jaw")

Temporal range: unknown to recent (??? - present)

Information:

If the cave clicker is the so-called monkey analogue of the Akamanucha cave system, then the bonecracker is the lion looking for a bite-sized meal to tide him over to his next feast.

Typically approaching the physical dimensions of a polar bear but weighing less than half as much, the largest members of this species would be able to contend with the theropods who stalk the surface above, reaching nearly 20 feet in length and over 700 pounds. In fact, this animal is so large for an invertebrate, breaking the previously understood upper limit for arthropod body size several times over, that it has actually been suggested by some researchers that something equivalent to abyssal gigantism may be the reason for why it grows so big, though the more conspiracy-inclined suggest genetic manipulation from high lifeforms is at play. As the cave is known to sit near volcanic fissures and is therefore able to support such a large and vibrant ecosystem, it has been suggested that it may also be a product of highly nutrient-dense water and prey animals allowing this animal to grow to a much larger size than should otherwise be plausible. However, its disproportionately large jaws do not seem to match the size of its prey, which are rarely larger than a sheep, suggesting that it may have been specialized to hunt an especially large cave animal which has since gone extinct.

Whatever the case, this creature’s anatomy is so confusing, being jokingly described by one of the scientists who retrieved the holotype specimen as, “the result of a one-night stand between an entelodont and a crustacean of some sort”. So baffling was this animal, in fact, that initially, scientists weren’t able to figure out what specific clade of arthropods it belonged to (if it was even an arthropod to begin with). However, genetic analyses and studies on its morphology finally revealed it to be a stem-group arthropod nested amongst the paraphyletic dinocaridids, being particularly closely-related to an inconspicuous opabiniid found on the surface in coastal tidal ecosystems known as the *elephant prawn*, with which it shares a most recent common ancestor over 450 million years ago. This solves one question but still leaves many left unanswered, such as how the jaw structure came to be and, more glaringly, how it, along with several other species descended from ocean-dwelling clades, ended up in the caverns. The prevailing theory is that the caverns were once connected to the oceans via an inland sea, and as the inland sea dried up, many of the creatures became trapped in subterranean lakes and rivers within the caverns, eventually moving onto land and adapting to life within the caves. However, as no transitional species which would link the features seen in the bonecracker to its less derived cousins has been found, this is difficult to verify.

With a jet black, iridescent body, white setae, and tail fins which shine bright red and violet spotted patterns when in UV light, this creature is as beautiful as it is frightening, a pinnacle of the cave’s deceptive beauty. Though larger predators exist in the Akamanucha cave system, it appears that none are willing to directly challenge this creature, a beast clearly feared by both predator and prey alike, and from what has been confirmed by both cameras and direct observations, other large predators either vacate the upper levels of the cave at night entirely to avoid this animal or hide away wherever they can as its makes its nightly vertical migrations up to the upper levels of the cave system in search of food, the means by which it times these migrations still completely unknown. Indeed, this animal appears to be the apex predator of its cavernous ecosystem, unafraid to bully similarly-sized predators out of kills. In fact, it won’t even tolerate its own kind under the best of circumstances, and when two bonecrackers cross paths, the ensuing scuffle often ends in the death of one or both parties, its characteristic rasping shrieks and “roars” being a way of notifying other members of its species of its position and not to come near. In fact, its aggression towards other species has made it challenging for researchers to even get close enough to properly study this animal, and it has been implicated in many attacks on researchers, including at least one death where it managed to decapitate one unfortunate researcher who had stumbled to the ground trying to flee from the animal. A sight-based predator, it can see a wide range of color despite the rather dark and monochromatic depths it dwells in during the day, with an exceptional ability to see UV light. This ability allows it to spot prey from far away and to better distinguish its prey from the faint bioluminescent hues given off by the fungi of the cave. Because its sight is so well-developed, most researchers venturing into the bowels of the cave keep flares on them in the event that they encounter one of these creatures. By contrast, however, its hearing and sense of smell are rather rudimentary if not highly underdeveloped.

Despite its social and dietary behavior being well-documented for a creature which is relatively understudied, next to nothing is known about its reproductive biology. However, most evidence points to internal fertilization and an ovoviviparous nature, rearing only a handful of young at a given time to ensure the best chances of their survival. Remarkably for a creature of their size, they are believed to have incredibly short lifespans, likely living no more than 20 years. Their population size is likewise believed to be rather small, possibly no more than a few thousand (at most) at a given time. Much like the cave-clickers they seemingly prey upon, none of the specimens captured and brought to the surface survived long after arriving to the surface, dying within days of surfacing.

While there are no unambiguous interactions between humans and bonecrackers prior to the mid-21st century AD, and these creatures appear to be entirely absent from cave paintings found in other areas of the caves, there is a fringe theory amongst some scientists that these animals inspired traditional depictions of demons in the native folklore of the human inhabitants, as the underworld in the folklore of the Xenogaean people (the inhabitants of the country of Xenogaea, which occupies the archipelago) is described as being remarkably similar to the surface world in many aspects, having its own native flora and fauna as well as intelligent species of varying moral dispositions. However, they considered the underworld creatures to be twisted reflections of that on the surface, nightmarish creatures which were unrecognizable to the surface-dwelling world. As highlighted previously, however, since there are no confirmed interactions between the two species in antiquity, this cannot be proven beyond a shadow of a doubt. However, seismic equipment has picked up readings of possible manmade structures at the very bottom of the cave, and trackers would seem to indicate that bonecrackers congregate near these in surprisingly large numbers, more than would otherwise be expected for such a territorial animal. Some suggest these creatures are guarding something, perhaps something which humanity is not yet supposed to see, while others believe that they simply use these structures as a place to shelter. Regardless, these creatures appear to guard many secrets, and not just the ones related to their own biology…

#scifi#fantasy#speculative evolution#novella#scififantasy#speculative biology#speculative fiction#speculative zoology#worldbuilding#creature art#creature design#fantasy creature#fantasy worldbuilding#sci fi creature#scifi worldbuilding#dinocaridida#creature

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

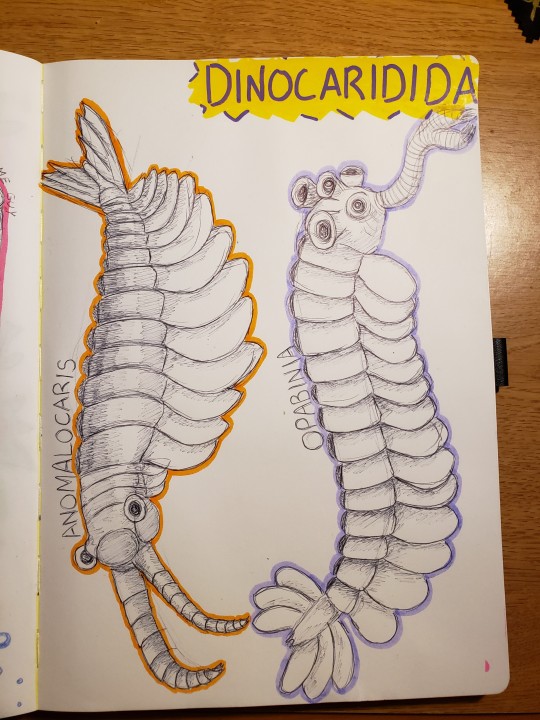

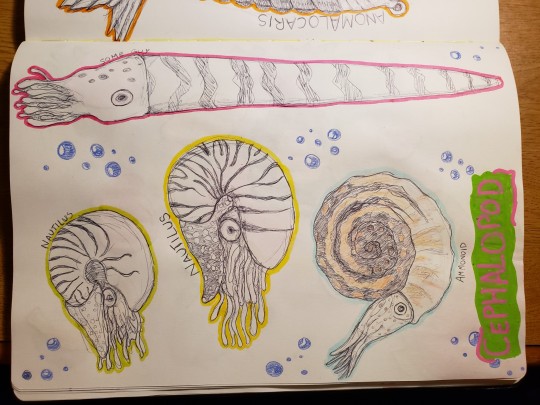

Round two

I was in the mood for some bug doodles

Feel free to give suggestions for more

#Arthropoda#Insecta#Zygentoma#Lepismatidae#Phasmatodea#Dinocaridida#Radiodonta#Anomalocarididae#Arachnida#Opiliones#Sclerosomatidae#Xiphosurida#Limulidae#Neuroptera#Myrmeleontidae#Araneae#Salticidae#Lepidoptera#Saturniidae#Art#Ancient#Aquatic#Brain worms

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinocaridida is a proposed fossil taxon of basal arthropods, which flourished during the Cambrian period and survived up to Early Devonian. Characterized by a pair of frontal appendages and series of body flaps, the name of Dinocaridids (Greek for deinos "terrible" and Latin for caris "crab") refers to the suggested role of some of these members as the largest marine predators of their time. Dinocaridids are occasionally referred to as the 'AOPK group' by some literatures, as the group composed of Radiodonta (Anomalocaris and relatives), Opabiniidae (Opabinia and relatives), and the "gilled lobopodians" Pambdelurion and Kerygmachelidae.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

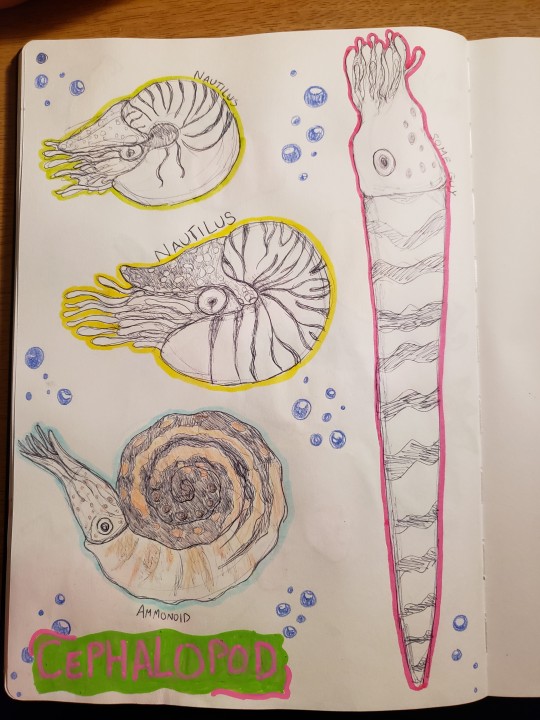

no one:

the cambrian explosion/GOBE: look at how many fucked up little guys i can make

#i love drawing these guys <3#rip to everyone except the nautilus#avi's art#cambrian explosion#ammonoid#nautilus#opabinia#anomalocaris#cephalopods#dinocaridida#gobe

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kid in picture book: I wish there still were dinosaurs

Me: I wish there still were dinocaridids

#paleontology memes#cambrian fauna#paleontology#prehistoric animals#prehistoric life#dinocaridida#dinocaridids#radiodonta#anomalocaris#frilly lobster sharks#i love them#screw dinosaurs

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

by the way i tagged the last post #A TINY ANOMALOCARID!! but I'm well aware the name is technically anomalocarididae and therefore "anomalocarids" is incorrect and should be "anomalocaridids". wikipedia states linguistic justification is off of this sentence: "class Dinocarida (linguistically corrected here to Dinocaridida, based on the Latin caris/caridis and the taxonomic suffix -ida)" from xianguang et al 2006--since the stem of caridis is carid-, when you add the family suffix it becomes carididae. this is indeed technically how you latin your family names.

HOWEVER!!!

article 29.3.1.1 of the 5th edition of the ICZN states in the case that a stem ends in -id already, these letters may be elided before adding the family suffix, and in fact commonly have been. there was NO need for xianguang et al to make this "correction" except for being fucking pedants i guess and given that first of all, anomalocaridae is not in alternate use so there can't be any confusion, and second of all, not eliding the first -id makes family names way fucking harder to pronounce, i reject this!! taxonomy isn't real latin and you're just showing off!!

this happened to ragworms/Nereis too even though nereidae was described first (1865) and had priority SOME 1970s bitch (pettibone im looking at you) "corrected" it to nereididae without even the grace to explain his pedantry in the paper. he was just like "i know a lot about latin and i want to make this shit hard to pronounce" and anyways that's why i disown taxonomists

#no offense meant to taxonomists. some of my best friends are taxonomists#on science#extinct critters#quilltxt

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Radiodonts were early arthropods with specialized frontal appendages, disc-like mouths, complex compound eyes, and swimming flaps along the sides of their bodies. Once considered to be bizarre "weird wonders" of the Cambrian Explosion that represented a failed evolutionary experiment, we now know that they were actually a highly diverse and successful lineage that lasted for at least 120 million years.

While some radiodonts were the largest animals of their time periods, Stanleycaris hirpex here was one of the smallest known members of the group – although at around 10cm long (~4") it was still respectably big compared to most other Cambrian animals.

Discovered in the Canadian Burgess Shale deposits (~508 million years ago), it was originally known only from isolated frontal appendages and mouthparts, and had been assumed to be a fairly typical member of the hurdiid family. But the recent discovery of over 200 new fossils, including some exceptionally well-preserved full body specimens, has catapulted it directly from being poorly-known into now being one of the most completely known of all radiodonts.

And it had a very big surprise for us, right in the middle of its face.

It turns out that Stanleycaris had a huge third eye, unlike anything ever seen in a radiodont before. A large unpaired eye was also part of the five-eyed arrangement in opabiniids and Kylinxia, and finding a similar example in radiodonts too raises the possibility that this sort of well-developed "median eye" may have been more widespread in early arthropods than previously thought.

Along with the third eye, some of the Stanleycaris specimens preserve fine internal details of its nervous system and show that its brain was made up of two segments instead of the three seen in modern arthropods. It also had gills positioned on its underside, unlike most other radiodonts which had them on their backs.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#stanleycaris#hurdiidae#radiodont#dinocaridida#arthropod#panarthropod#invertebrate#cambrian explosion#art#look at this delightfully goofy friend#i love them#the cambrian is ALWAYS even weirder than we thought it was

510 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is by the artist @/ni075 on twitter as well! he has many fantastic reconstructions of radiodonta and dinocaridida in general :)

PSA for anomalocaris fans: this is the most accurate and up to date reconstruction of anomalocaris! spreading awareness because i only found out recently and made some artistic blunders

more info can be found online, i just wanted to let ppl know cause google image results are pretty varied in accuracy

310 notes

·

View notes

Photo

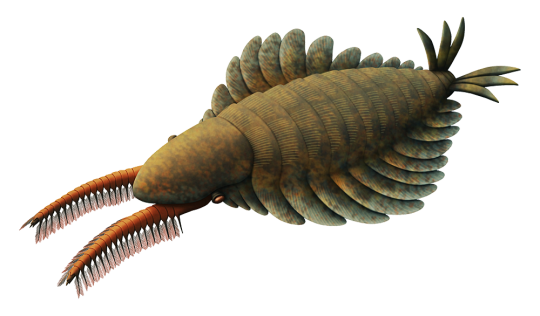

Ever since the bizarre anatomy of Opabinia was first recognized in the 1970s, it's been a persistently unique "weird wonder" of the Cambrian period. Over the decades we've figured out that it was an early type of arthropod in an evolutionary position between lobopodians and radiodonts, but this whole time it's still been sitting there alone as the only known representative of a weird stem-lineage with no other known close relatives.

…Until now!

A fossil from the Wheeler Shale in Utah, USA (~507 million years ago) that was originally thought to be a tiny radiodont has been re-studied, and now we finally have another member of the opabiniid family: Utaurora comosa.

Only about 3cm long (1.2"), Utaurora had 15 pairs of swimming flaps along the sides of its body, and a tail region with a 7-part fan and a pair of serrated spines. Hair-like gill blades covered both its back and the bases of its swimming flaps, and although its head region was poorly preserved it probably had an arrangement of 5 eyes and a long flexible claw-tipped proboscis similar to that of Opabinia.

Its discovery extends both the geographical and temporal known range of opabiniids, and suggests that their continued scarcity in other Cambrian fossil sites compared to other soft-bodied arthropods may simply be because they were just incredibly rare animals in those habitats at the time.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#utaurora#opabiniidae#dinocaridida#gilled lobopodians#panarthropoda#arthropod#invertebrate#cambrian explosion#art

482 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Time for some more PBS Eons commission work!

The radiodonts Lyrarapax and Tamisiocaris, from "How Plankton Created A Bizarre Giant of the Seas" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G0oKBPZODhM

The rhynchocephalians Sphenotitan, Clevosaurus, and Kawasphenodon, from "When Lizards Took Over the World" https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=peeX3PKOE_w

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#pbs eons#lyrarapax#tamisiocaris#radiodonta#dinocaridida#arthropod#invertebrate#spenotitan#clevosaurus#kawasphenodon#sphenodontia#rhynchocephalia#lepidosauria#reptile#art

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #42: Radiodonta – The Strangest Shrimps

Once the dinocaridids started exploring active swimming lifestyles, one branch of this group quickly became incredibly successful and diverse: the radiodonts. With muscular swimming flaps, head carapaces, stalked compound eyes, disc-like mouths, and large spiny front appendages, they occupied a wide range of ecological roles – and some of them went on to became giants, some of the largest animals of their time.

They were some of the closest relatives to the ancestors of the true arthropods (or "euarthropods"). And while the earliest radiodont fossils are known from about 518 million years ago, much like other panarthropods their actual evolutionary origins have to go back much deeper into the early Cambrian since they already lived alongside representatives of various early euarthropod groups.

———

The first radiodont ever discovered is also the most famous of the group, Anomalocaris canadensis from the Canadian Burgess Shale deposits (~508 million years ago).

Initially discovered in the late 1880s, only isolated front appendages were found and they were misidentified at the time as being parts of crustaceans. In the early 1910s an individual mouth cone was thought to represent a jellyfish, and a fairly complete body fossil was interpreted as a sea cucumber. It wasn't until 1985 that all these separate pieces were finally recognized as belonging to one type of surprisingly large Cambrian animal, which was given the earliest name assigned to any of the constituent fossils – Anomalocaris, meaning "strange shrimp" – and thankfully that tuned out to be a very fitting name for a bizarre-looking distant cousin of crustaceans and other arthropods.

Since then around 35 different species of radiodonts have been discovered, and Anomalocaris has turned out to represent just one branch of this lineage.

It had 13 pairs of large body flaps and 3 smaller pairs on its neck region, along with a vertical three-part tail fan and rows of hair-like gills attached to each body segment along its back. Its stalked compound eyes were made up of around 16,000 lenses each, and it would have had incredibly sharp vision comparable to modern dragonflies. Several sclerites formed a carapace around its head, with a tri-radial mouth underneath and a pair of large jointed spiny appendages at the front.

While some past estimates of its size are now known to be rather exaggerated (or based on different radiodont species entirely), it was still a relatively huge animal for the time at around 50cm long (1'8"). Its raptorial front appendages suggest it was an apex predator, with a lack of wear on its mouthparts indicating it probably mostly fed on soft-bodied animals.

The closely-related Lenisicaris and several other still-unnamed species of Anomalocaris are known from various mid-Cambrian fossil sites that at the time were tropical or subtropical latitudes, showing that anomalocaridids were widespread in warm waters around the world. Ultimately these predatory radiodonts lasted for at least 20 million years during the mid-Cambrian, with the last known anomalocaridid fossils coming from the Weeks Formation in Utah, USA (~499 million years ago).

———

Related to the anomalocaridids, the amplectobeluid radiodonts had front appendages with a highly enlarged first spine, forming a specialized grasping pincer-like structure.

Amplectobelua symbrachiata is known from the Chinese Chengjiang fossil deposits (~518 million years ago) and was around the same size as Anomalocaris at about 50cm long (1'8"), making it one of the largest known Chengjiang animals.

It had 11 pairs of large swimming flaps with strengthening rays along their front edges, and while it's unclear if it had a tail fan it did have a pair of long streamer-like appendages at its rear end. Underneath the smaller pairs of flaps on its neck there were at least 3 pairs of "gnathobase-like structures" that would have been used to hold and shred up prey after transferring it from its pincer-like front appendages, chewing it up before passing it up to its mouth.

Several other amplectobeluids have been identified, including Lyrarapax and Ramskoeldia, and they also seem to have occurred mostly in tropical and subtropical waters during the mid-Cambrian. The latest known fossils of this family come from the Burgess Shale, about 508 million years ago, and much like their cousins the anomalocaridids they may have been wiped out around the time of the late Cambrian "SPICE" event, unable to cope with cooling oceans and rising anoxic conditions.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#anomalocaris#anomalocaridid#amplectobelua#amplectobeluid#radiodonta#dinocaridida#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art

181 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #43: Radiodonta – Splash Of The Titans

The most famous radiodont is the classic charismatic Anomalocaris, but there were plenty of other members of the group who explored very different lifestyles. Instead of big apex predators, some of them became equally large filter feeders – the whales of the Cambrian.

Tamisiocaris borealis was discovered in the Sirius Passet fossil deposits in Greenland (~518 million years ago). Known only from its front appendages and head shield, its full life appearance and size is unknown but it's estimated to have been between 35 and 70cm long (1'2"-2'4").

Amazingly the existence of this radiodont was actually predicted by a piece of speculative evolution artwork about a year before the discovery of its filter-feeding habits was published.

Its front appendages bore long pairs of spines, each covered in densely-packed bristles that would have functioned like sweeping nets, capturing numerous small planktonic animals from the water and bringing them close to its mouth so it could suck them in.

The eyes in this reconstruction are based on "Anomalocaris" briggsi, a closely related species that wasn't actually an Anomalocaris but hasn't been given its own genus name yet. Surprisingly for a radiodont it had unstalked eyes with vision adapted for low-light conditions, suggesting that it may have vertically migrated, spending daytime in the deeper twilight zone and moving up near the surface to feed on swarms of zooplankton at night.

Along with the recently-named Houcaris these unusual radiodonts make up the tamisiocaridid family, and like their cousins the anomalocaridids and amplectobeluids they seem to have been primarily restricted to the warm waters of tropical and subtropical regions. They were also a much shorter-lived lineage, only known from the "series 2" division of the mid-Cambrian between about 518 and 512 million years ago – and they were probably among the casualties of the end-Botomian mass extinction, when widespread anoxic conditions would have severely disrupted the complex planktonic food webs they depended on.

———

The final major branch of the radiodonts were the hurdiids, with fossils of this group known from all around the world.

They were characterized by their enormous head carapaces, sometimes so big compared to the rest of their bodies that they were little more than "swimming heads", and some species had two pairs of flaps on each body segment. Their front appendages were also uniquely shaped, with only a few of the segments each bearing a single massive spine lined with bristles. These spines usually curved inwards, creating a large "basket" that would have been used to capture small prey.

Titanokorys gainesi was a hurdiid recently described from the Canadian Burgess Shale deposits (~508 million years ago). Known from 12 specimens, it was one of the largest animals in that ecosystem rivalling its cousin Anomalocaris at around 50cm long (1'8").

Its huge carapace's streamlined spaceship-like shape led to it being nicknamed "the mothership", and the huge structure may have been used like a plough, shoving through seafloor sediment and sifting around with its front appendages to rake up all the small soft-bodied burrowing animals it uncovered.

Hurdiids were far more tolerant of low temperatures than their tropical relatives, found throughout the seas of the Cambrian southern hemisphere all the way into cold-temperate and subpolar waters. And this ultimately allowed them to outlast all the other radiodonts by far and survive throughout the first half of the Paleozoic Era – in the early Ordovician (~480 million years ago) the gigantic filter-feeding Aegirocassis reached sizes of around 2m long (6'6"), making it both one of the biggest animals in the world at the time and one of the largest panarthropods to ever live, while the last known hurdiid (and the last ever known radiodont) was Schinderhannes from the early Devonian of Germany (~400 million years ago).

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#tamisiocaris#tamisiocarididae#titanokorys#hurdiidae#radiodonta#dinocaridida#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#ceticaris

172 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #41: Dinocaridida

Probably evolving from Siberion-like lobopodians, the dinocaridids were an "evolutionary grade" of panarthropods that were closely related to the ancestors of true arthropods. These animals were characterized by specialized front appendages on their heads and large swimming lobes along the sides of their segmented bodies, and their group included some of the most famous of the Cambrian "weird wonders".

The earliest branches of the dinocaridids were the "gilled lobopodians", which had lobopodian-like legs on their undersides and gills on the upper surfaces of their body lobes. The flap-like structures may have initially evolved just to provide a larger surface area for respiration, but they were quickly co-opted for swimming purposes and opened up a whole new range of ecological opportunities to the ancestral dinocaridids.

———

Kerygmachela kierkegaardi from the Sirius Passet fossil deposits in Greenland (~518 million years ago) is one of the best-understood gilled lobopodians, known from around 15 specimens.

It had a pair of slit-shaped compound eyes underneath the bases of its spiny front appendages, along with another pair of small structures at the front of its head that may have been additional simple eyes. Its total length was about 17cm (~7"), and it had 11 body segments with rows of bumpy ornamentation along its back, gill-bearing flaps at its sides, small lobopod-like legs on its underside, and a single long tail spine.

It may have been an active predator snaring prey with its front appendages, although its small mouth size suggests it was restricted to feeding on fairly small planktonic animals.

The closely-related gilled lobopodian Pambdelurion is also known from the same location as Kerygmachela, and had comb-like spines on its front appendages that suggest it may have been a filter-feeder. Another similar animal from the Chinese Chengjiang fossil deposits (~518 million years ago) known as "Parvibellus" may also be related, but as of the time of this post its description hasn't yet been peer-reviewed or formally published.

———

And we can't have a Cambrian series without including one of the most charismatic and bizarre-looking early dinocaridids: Opabinia regalis.

Known from the Canadian Burgess Shale deposits (~508 million years ago), this 7cm-long animal (~1.5-2.75") seemed so strange when it was first properly reconstructed in the 1970s that the audience at the presentation laughed. With no evolutionary context for such an alien-looking creature at the time, it was initially assumed to be a "failed experiment" unrelated to any modern animal phyla – until later discoveries of similar Cambrian animals helped properly place it as a close relative of the "gilled lobopodians" and radiodonts.

It had five large stalked eyes on its head and a long flexible proboscis (resembling a vacuum cleaner hose) with a pincer-like structure at the tip, probably derived from a pair of fused grasping front appendages. Its backward-facing mouth was located on the bottom of its head, behind the base of its proboscis, and the rest of its segmented body had 15 pairs of overlapping swimming lobes and a three-part tail fan. Small triangular structures preserved on its underside may have been lobopodian-like legs.

It was probably a bottom-feeding predator or a detritivore, swimming along above the seafloor using its proboscis to probe around, snatching up small soft prey or organic material and then passing it up to its mouth. If the "triangles" on its underside were legs then it may also have been able to walk.

Its fossils are quite rare in the Burgess Shale, with only a few good specimens known, either due to it already being a very rare member of the ecosystem or because its free-swimming lifestyle made it so much less likely to be preserved.

And while we now know where it fits into the panarthropod family tree, Opabinia is surprisingly alone in its spot between the "gilled lobopodians" and radiodonts. No other close relatives have been found, no similarly trunked many-eyed weirdos… with a couple of possible exceptions.

The slightly older Myoscolex from the Australian Emu Bay Shale (~514 million years ago) may be a close relative of Opabinia, although the specimen is rather ambiguous and this interpretation is controversial, and it might instead be a polychaete worm. Additionally a not-yet-formally-named fossil from the Wheeler Shale in Utah, USA (~507 million years ago) may also represent a new opabiniid.

EDIT: The Wheeler opabiniid has been named, and it’s now called Utaurora comosa!

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#kerygmachela#opabinia#opabiniidae#gilled lobopodians#dinocaridida#lobopodia#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#go home evolution you're drunk

150 notes

·

View notes

Link

New Cambrian weirdo!

#paleontology#palaeoblr#new species#kylinxia#radiodonta#dinocaridida#arthropod#stem-arthropod#cambrian explosion

111 notes

·

View notes