#codex mendoza

Text

c. 1540 CE: a young man from Chalco, and his dragon.

#em draws stuff#em is posting about temeraire#temeraire#temeraire worldbuilding collection#<- tag for organizing when I'm drawing stuff that is temeraireVerse but not in the line of the plot of the books themselves#for school reasons I have been reading a lot about 14th-17th century mesoamerica#and thus am Interested in how that would have potentially played out in temeraireverse...#anyway! not sure if I'll draw these two again but I Have given the lad a day sign name (five deer) so I could Potentially. who can say.#haven't come up with a name for the dragon yet... maybe cipachcoatzin would work if can't think of anything else#<- Please Forgive My Dubious Command of Classical Nahuatl Grammar I Am But A Student#on that note zoomorphic interlace is not very much a style from this period/region but it helps me with composition things#five deer himself is mostly based on the illustration of the tlacuilo's son in the codex mendoza#the dragon is drawn more from a fusion of older scribal styles (ie. the codex borgia) and my own shorthands for dragon anatomy

523 notes

·

View notes

Text

What was it like to be an Aztec kid? According to this document, not so great. This page of the Codex Mendoza shows us a boy (left) and girl (right) at ages 11-14. We see the naughty tweens punished at ages 11 by being held over burning chili peppers until they cry. Then, at age 12, the boy is tied up until he behaves, while the girl does chores around the house. By ages 13 and 14, they’ve apparently learned to behave: the boy is helpfully collecting reeds and fishing while the girl makes tortillas and weaves.

Much more on Aztec life here:

{Buy me a coffee} {WHF} {Medium} {Substack}

340 notes

·

View notes

Text

the interdependence of mesoamerican art

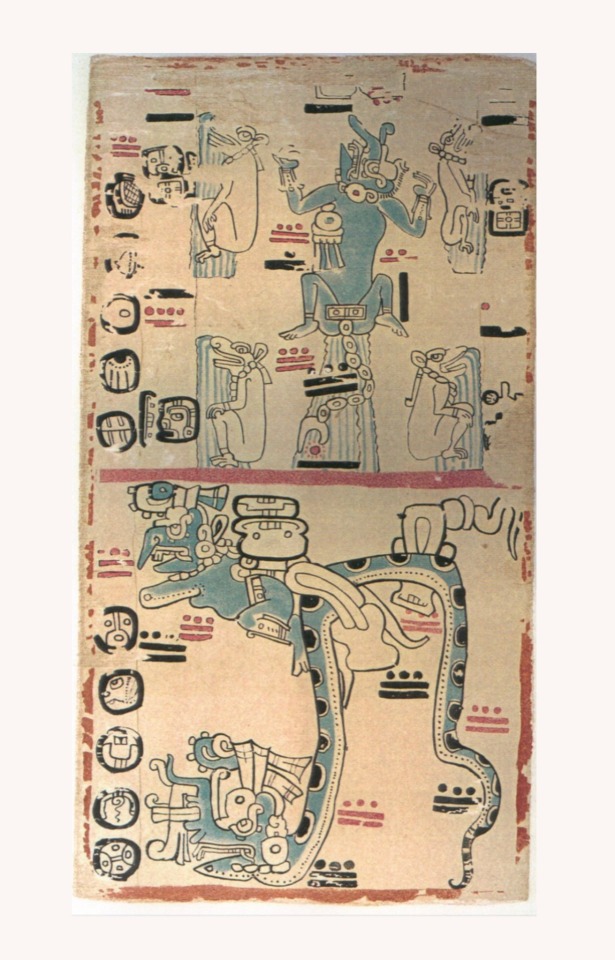

pyramid at la venta (circ. 800 bce), la venta / kukulkán pyramid (circ. 440-1050 ce), chichén itzá / temple of the morning star (circ. 850-1150 ce), tula / temple of the warriors (circ. 900-1050 ce), chichén itzá / colossal head 1 (circ. 800-400 bce), san lorenzo / coyolxauhqui's head (1486-1502 ce), tenochitlán / madrid codex (circ. 1250-1450 ce) / mendoza codex (circ. 1541)

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aztec Codices: Mesoamerican Literature

How do we know when things happen in history? Not by using time travel. Often from books, or a series of manuscripts (a Codex). Here are some from the Aztec era

The Aztecs have a number of these, 38 major ones at least. But let's discuss three of them and what they have in them

Codex Aubin (1567 - 1608)

Coming in at 81 pages and being established in 1567 and having it's last page dated at 1608 (just at the start of Spanish rule). Essentially it starts by detailing the founding of Tenochtitlan (hopefully I spelled that right). But it also provides the Aztec perspective on what happened during the Spanish conquest of the city including the smallpox epidemic. It does make a reference to the massacre in Tenochtitlan in 1520. James Lockhart got his hands on Aubin and managed to identify a main author of sorts. The author used a combination of older Codices, oral history and some eyewitness testimonials. The Codex is complimentary to the Codex Florentine which discusses similar events from a different angle. This Codex can be found in the British Museum.

Codex Boturini (1530 - 1541)

Weighs in at around 22 pages, it's written in a combination of glyphs and Nahuatl. It talks about the migration of the Aztec people from Atzalán and were one of the tribes of the Azteca. It then talks about the Azteca becoming into the Mexica and how they were chosen by god to form the city of Tenochtitlan. The Codex Aubin picks up the story from here on out.

Codex Mendoza (1541-1552)

It consists of 83 pages or so, it was commissioned by the Viceroy of Spain at the time and named after Don Antonio de Mendoza. It was made by native artists on European paper. It consists of three sections. The first section is a summation of 200 years of Aztec history. The second section was a list of cities invaded by the triple alliance (possibly stolen from a different Codex). The last section was a currency conversion table with European currency. This Codex can be found in the library at Oxford.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyways, mocte clothes references I can pick up from his design

References In order;

1. Antonio Rodríguez’ portrait of Moctezuma II (late 17th century)

2. Durán Codex’ ; Piece of a depiction of Moctezuma II’s coronation

3. Stone that likely atributes the date of coronation of Moctezuma II

4. Mendoza Codex ; Moctezuma II’s palace

5. Mendoza Codex ; Moctezuma II himself

6. Boriga Codex ; Tezcatlipoca

7. Jaguar jaw

8. Mendoza Codex ; aztec warriors likely tlacochcalcatl

#;m.octezuma II#i put his eye's look as in reference to his name's meaning 'he is the one who frowns like a lord'#maybe its all coincidence and im looking toomuch into it god knows#tezca is there mostly as ref to mocte's color palette consisting on mostly yellow and black#and if he is truly meant to be tezca's representation of earth in f.go's plot#there's also this lil fact; mocte had a room that was all pitch black meant for his times of meditation#i kinda doubt his color palette is a reference to the importance of this room to him and the serenity this color gives him but o k#a lot of the portraits and drawings that have been collected of him feature him wearing clothes that have this typeof knot#me thinks that the cloth tied around his waist is tied in a similar manner#the patterns on the edge are similar in an reverted way to the one of his cloak in ref 2#then the collar area reminds me of the collars of aztec warriors#jaguar bc the ties with tezca and the importance of jaguars in general#did u know he had a zoo built when his reign was arround? they held mostly birds but there were a lot of other animals associated with#figures of gods#they were well fed and taken care of however this zoo latergot destroyed once he died#anyways its late BUT YEAH#;about#about#i kinda wanna do this with my ithert s.ervant muses 😳👉👈

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dough statue of Huitzilopochtli as the Tzitzimitl Omitecuhtli, wearing the skulls and crossbones cape and receiving offerings of dough bones during Toxcatl, Florentine Codex

Huitzilopochtli Statue

Huitzilopochtli the most celebrated god of the Aztecs, celebrated during the month of Toxcatl.�� A god of war and the sun, also representing the finding of Tenochtitlán. The Aztecs believed that four priests carried Huitzilopochtli in the form of a hummingbird. With the god directing them to find "an eagle perched on a cactus that bore a large red fruit" symbolizing that they had found their new home away from Aztlán. They had found it with Tenochtitlán creation.² During the festivities for Huitzilopochtli the Aztecs would make a statue of him in the temple of Huitznahuac, using "Fish-amaranth dough" to make it seem as if he had flesh. He was then decorated with human limbs and was covered with a cape made of feathers.³ Huitzilopochtli's statue also wore "a cloth jacket or vest decorated with the image of human bones. It wore a distinctive hat made of paper that was wider at the top than at the brim so that it looked like a bowl and was decorated with feathers and a flint knife," his attire representing death. After his image was made he was moved to a sanctuary where rituals would be done in his presence. Such as cutting off the heads of four quails, salted and eaten by the monarch.⁴ Huitzilopochtli was also celebrated in the fifteenth month of Panquetzaliztli, which was significant to the Aztecs because they had to pay tribute to the Triple Alliance (Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan)⁵, which only required in four months.⁶ During Panquetzaliztli statues of Huitzilopochtli were also made, however, this image of him was very different. Being instead of a human-sized deity impersonator (ixiptla) on a wooden frame made from tzoalli.⁷ Tzoalli was a mixture of ground amaranth seeds and dark maguey syrup which made a paste used to make statues of their gods. This paste was made by young women or girls aged twelve to thirteen who were dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. Making the final dough rested on the hands of the priests, who carefully made sure it was pristine with no debris. Then Huitzilopochtli was ready to be created.⁸

---------------------------------------------------

Bibloagrpahy

"Codex Mendoza." In Biographies and Primary Sources, edited by Benson G Sonia, Hermsen Sarah, Baker Deborah J., 209-219. Vol. 3 of Early Civilizations in the Americas Reference Library. Detroit, MI: UXL, 2005. Gale In Context: World History. URL

Boone Elizabeth H. Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: The Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 79, 1989. URL

Schwaller, John F. The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli. University of Oklahoma Press, 2019.

----------------------------------------------------

Elizabeth Boone, Incarnations of the Aztec Supernatural: The Image of Huitzilopochtli in Mexico and Europe, (Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 79, 1989,) p1

Sonia G. Benson, Sarah Hermsen, Deborah J. Baker, Vol. 3 of Early Civilizations in the Americas Reference Library (Detroit, MI: UXL, 2005. Gale In Context: World History,) URL

John F. , Schwaller, The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, (University of Oklahoma Press, 2019,) p129

Schwaller John F., The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, p130

Schwaller John F., The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, p7

Schwaller John F., The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, p9

Schwaller John F., The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, p130

Schwaller John F., The Fifteenth Month: Aztec History in the Rituals of Panquetzaliztli, p95

0 notes

Text

Cacao in Mesoamerican Society

Chocolate is arguably the most popular confection in the western world. The Swiss alone consume an average of 19.8 pounds of chocolate per person annually. However, chocolate wasn’t always a mass produced confectionery. For centuries, chocolate was produced in small quantities for a select group of people. Cacao’s botany resulted in cacao and chocolate being used to reinforce social hierarchies and connect humans with the gods.

Cacao’s botany had unique social, political, economic, and societal implications for Mesoamerica. However, before discussing cacao’s effects on Mesoamerican societies, it is important to understand the origin of cacao cultivation and nature of cacao production. Cacao was first cultivated by the Barra people of Soconusco, Mexico, a civilization that predates the Olmec; the Olmec then perfected the processing of chocolate, and this process spread to other civilizations. Cacao is particularly difficult to cultivate. For starters, cacao only grows within 20° of the equator in a temperature range of 60℉ and 95℉; furthermore, cacao trees can only grow in shade, and must be planted under larger trees for protection against the Sun. After some time, cacao trees will start to produce flowers; only 3 of every 1,000 flowers on a cacao tree will become cacao pods. Once the cacao pods are mature, they must be delicately harvested by a large workforce, using machetes to carefully separate the pods from their roots. After being harvested, the cacao pods are cut open, revealing the cacao beans, the component used to make chocolate. Cacao beans must undergo a series of steps to be consumable, including fermentation, drying, roasting, and winnowing. First, cacao beans are left to ferment for several days to remove the pulp from the beans. Next, the beans are dried out in the Sun; the length of this drying period depends on the weather. After being dried, the beans are roasted. Next, the beans are winnowed; winnowing is the process in which the edible cacao nibs are separated from the inedible shells. Finally, the nibs are ground and blended; this resulting liquid, called chocolate liqueur, is molded into the desired shape, creating chocolate. The limited growing region and intensive processing of cacao meant that chocolate in Mesoamerica was a limited commodity.

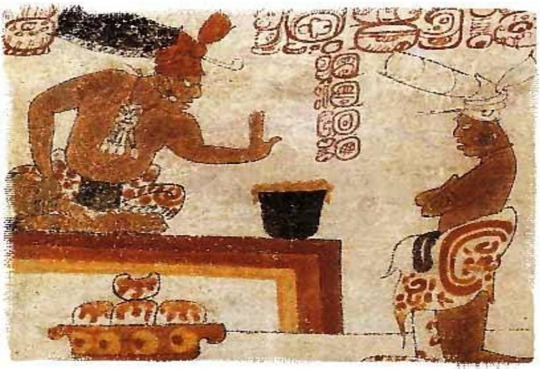

As stated earlier, cacao’s botany led to it being a limited good in Mesoamerican societies. This, in turn, resulted in cacao being used to reinforce societal hierarchies. As cacao was a limited good, only nobles could readily afford it. Chocolate was also difficult and time consuming to prepare; instead of producing the chocolate themselves, nobles had servants prepare their hot chocolate beverage. To further show off their wealth, nobles had their chocolate drinking vessels intricately decorated with images depicting cacao being served to nobles and the gods. The image below is an example of how chocolate was used to reinforce social hierarchies. In the painting, the man serving the chocolate is kneeling, while the man consuming the chocolate is sitting on a throne, showing a class difference between the two. Historians know this beverage is chocolate due to the foam on the top of the drink, as various accounts describe Mesoamerican chocolate as being a frothy drink.

Additionally, the Mexica, also known as the Aztecs, used cacao beans as a form of currency. According to the Codex Mendoza, 4 1⁄2 hours of work was equivalent to 1 cacao bean. When a Mexica noble drank a cup of chocolate, they were literally drinking money, reinforcing their status as the elite.

Not only was cacao used to reinforce social hierarchies, but it was also used to connect mankind to the gods. In the Maya myth of origin, cacao was one of the primary ingredients used by the gods to create mankind, along with yellow corn, white corn, and paxtate. This link between humans and the gods was strengthened further with cacao’s importance in the continuation of the life cycle. In the Madrid Codex, the gods are displayed as watering cacao trees with their blood; when humans consume cacao, they are nourished by the gods. In order to nourish the gods in return, humans would offer chocolate and other foods to the gods during festivals like the Five Dangerous Days; these ceremonies were key in continuing it. Cacao trees also featured in the pantheon of sacred trees, trees which were responsible for holding up the sky and connecting it to the earth, acting as a pillar between the two realms.

Cacao held great significance in Mesoamerican society. As a result of cacao’s limited growing region and labor-intensive cultivation process, cacao was a limited commodity. This led to cacao being used to reinforce social hierarchies and connect mankind with the gods.

Works Cited

Castillo, Lorena. “The Most Surprising Chocolate Statistics and

Trends in 2024.” Gitnux.org, December 16, 2023.

Juarez-Dappe, Patricia. “Cacao Origins.” YouTube, August 21, 2020.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y3NoKpG2PtU

Juarez-Dappe, Patricia. “Chocolate Encounters.” YouTube, August 26, 2020.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G8BW-HHWI88

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chocolate Encounters: Mexica and Spaniards

When two civilizations clash for the first time, there is an inevitable exchange which takes place. Goods, ideals, and germs are all traded between the two peoples, and each is changed by the other. In many instances, such as the Spanish Conquest of the Mexica, one party is considered the “dominating” party. The dominating party often leaves a greater impression upon its counterpart in the exchange, but cacao can show us how the “conquered'' society has the ability to dominate the tastes of their conquerors. In the case of both the Mexica and the Spanish, cacao penetrated the tastes and preferences of the conquering nation so thoroughly that the product itself became native to the conquerors in its own way. In essence, chocolate colonized the tastes of civilizations that encountered it on the warpath.(1)

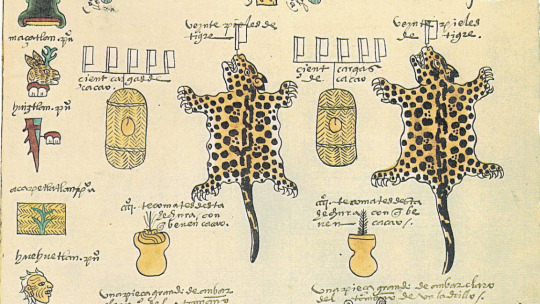

The Mexica are well known for their militaristic tendencies. Many civilizations across Mesoamerica learned firsthand how the Mexica could force them into submission, including the Mayans who were conquered by the Mexica around the twelfth to fifteenth century. The Mexica had previously never come into contact with cacao, but once they were introduced there was no going back. In noting that the Mexica demanded tribute from their conquered subjects, it could be said that the Mexica had greater influence in the exchange between themselves and their conquered subjects. However, in examining what it was that the Mexica demanded in those tributes, the lines become blurred. The Codex Mendoza contains a record of some required tributes that were collected and brought to the capital in Tenochtitlan. Among these shipments was nearly 10 million cacao beans every year from Soconusco, one of the highest producing cacao regions on the continent at that time. For a society who had never tasted it before, the Mexica had a clear desire for as much cacao as they could get their hands on.(2) The practice of chocolate-making seeped into the customs of the Mexica so thoroughly that when the Spanish arrived in the Americas, the Mexica found themselves in a similar position to the nations which they had previously conquered.

Hernan Cortes arrived in Mesoamerica with one goal above all else: profit. The Spaniards who made the journey to Tenochtitlan in the early 16th century saw amazing things they could not believe, so they naturally desired it for themselves. Among these things was, of course, cacao beans and chocolate beverages. Interestingly, the Spanish colonizers first sought to control the bean itself as a form of currency rather than sustenance, but it was not long before the use of cacao for chocolate beverages erupted in popularity with Spaniards. Though some found the drink to be bitter or unpleasant, Spanish men and women integrated chocolate into their diets for the supposed health benefits and to display status. In Mexica social settings, drinking of chocolate was reserved for the elites or the guests of the elites; when Cortés and his crew first arrived in Tenochtitlan, they were served chocolate in Moctezuma’s chambers as a demonstration of power by the Mexica ruler.(3) Spanish interest in cacao became so high that in 1585, the first shipment of cacao beans arrived in Europe packed with all of the common additions needed to make chocolate. The chocolate beverage which the Mexica had co-opted from their conquered subjects had once again found its way into the palette of the conquerors.

In Europe, chocolate served a uniformly nutritional purpose. The bitterness of the drink was once again received poorly, and the addition of honey and sugar became the standard for most recipes.(4) The Spanish colonizers had arrived in Mesoamerica with the intention of making money from this valuable crop. In Europe, however, where the raw cacao bean was not monetarily valued in the same way, chocolate was enjoyed purely as a product of the societal exchange which causes two civilizations to invariably change one another.

Between the Mexica’s adoption of chocolate practices and the evolution of chocolate as it traveled across the sea to Europe, it can easily be said that cacao has survived due to its compelling nature, enticing colonizers as both a currency and a confection. When examining this fact in the context of conquest, we can surmise how the tastes of the conquered will often influence the conqueror perhaps even more so than the inverse.

Patricia Juarez-Dappe, “Chocolate Encounters,” YouTube video, 37:27, August 26th, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G8BW-HHWI88

Juarez-Dappe, “Chocolate Encounters”

Harwich, Nikita. “The Chocolate Trade in Mexico Territory: from Aztec to Colonial Times.” Artes de México, No. 103, p. 76

Juarez-Dappe, “Chocolate Encounters”

0 notes

Text

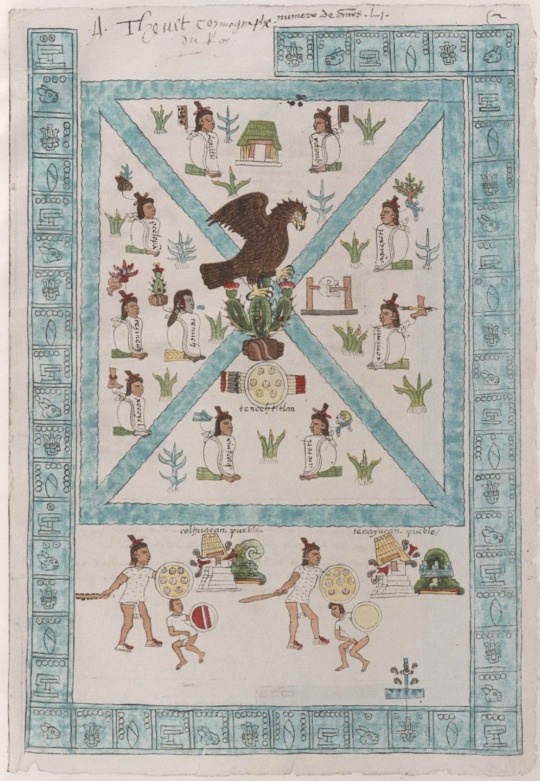

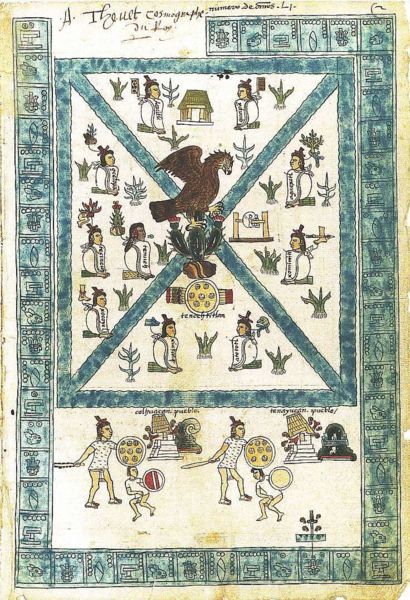

81. Frontispiece of the Codex Mendoza

By the Viceroyalty of New Spain

Created c. 1541-1542 CE

Ink and color on paper

0 notes

Text

What kinds of information does the Codex Mendoza contain

Answer the following questions in 1-2 sentences.

This assignment requires a close examination of a page from the Codex Mendoza, a document commissioned by the Spanish in 1541-1542 CE and illustrated by Mexica artists. The Codex Mendoza is a hybrid document in that the images are created by Mexica artists but the accompanying text is written in Spanish. The book was commissioned by Spaniard Viceroy Antonio Mendoza in Colonial Mexico with the purpose of documenting Mexica culture and sending the information back to Spain.

Step 1: Read about the front page of the Codex Mendoza Links to an external site.

Step 2: Answer the following questions:

1. What kinds of information does the Codex Mendoza contain?

2. Where was the Codex Mendoza originally intended to be sent?

3. What do the blue-green diagonals on the front page of the codex symbolize?

4. What is represented at the center of the page?

5. How is Tenoch represented differently than the other men on the codex?

6. At the bottom on the page, how does the artist visually represent the military power of the Aztecs?

Step 3: Look at the original page of Folio 45 Download Folio 45from the Codex Mendoza,

Step 4: Look at the line drawing Download line drawingand English translation Download English translationof Folio 45

Step 5: Identify which six objects from Folio 45 are cropped hereDownload here

You may write your answers simply. i.e. Image 1 is________, Image 2 is__________, etc.

First appeared on essaybrooks.org

0 notes

Text

drawing will have you say sentences like 'how do normal people just stand there'

#news from the cupola#here I sit surrounded by my three tomes and a pdf of the codex mendoza. what do you do with your arms while you stand.#also. killing auguste racinet with my mind you're not HELPING

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's another page of the 1541 Codex Mendoza, which attempted to capture the history of the Aztecs before it disappeared. It shows us the conquests of a ruler named Axayacatl. The biggest conquest in Axayacatl’s career is depicted at the top — Moquihuix, lord of Tlatelolco, is falling from his burning temple in defeat:

Go deeper on this image and the rest of the Codex here:

{Buy me a coffee} {WHF} {Medium} {Substack}

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The Codex Mendoza was used to legitimize the Spanish conquest of the Mexica"

“The Codex Mendoza was used to legitimize the Spanish conquest of the Mexica”

The Codex Mendoza embodies an overwhelming tragedy: the fall of a civilization. The manuscript, created sometime between 1542 and 1552, is one of the most celebrated collaborative projects between Mexica artists and Hispanic performers in history. The narrative of the 71 folios of the mendoza it is a mixture of Nahua painting and writing with passages in the Spanish language; and covers the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Tributes paid by towns to the Aztec empire, from the Codex Mendoza, circa 1542.

#Aztec#Codex Mendoza#Mesoamerica#Culture#Mexico#Rare Books#Antique#Art#History#1500s#America#Central America

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

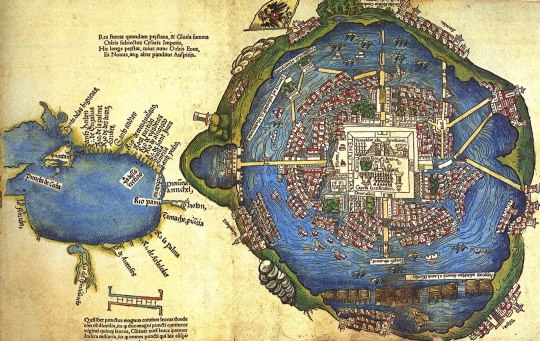

Representations of the city of Tenochtitlan, capital of the Aztecs.

Up right : second folio of the Codex Mendoza depicting the foundation of Tenochtitlan. Painted european paper, 1541-1542. Oxford University.

Up left : Tenochtitlan map given as a gift to Cortes around 1519-1521. Publicated in “Praeclara Ferdinandi Cortesii de nova maris Oceani Hispania narratio“, Cortes’ second letter to the emperor Carlos V in 1524. Newberry library, Chicago.

Bottom : “La Grande Tenochtitlan”, fresco by Diego Rivera, 1945. Palacio National, Mexico.

#mesoamericanaesthetic#tenochtitlan#codex#codex mendoza#cortes#map#mesoamerica#mexico#mexica#fresco#diego rivera

15 notes

·

View notes