#counting number of connected components in a undirected graph

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

C Program to find Connected Components in an Undirected Graph

Connected Components in an Undirected Graph Write a C Program to find Connected Components in an Undirected Graph. Here’s simple Program to Cout the Number of Connected Components in an Undirected Graph in C Programming Language. Undirected graph An undirected graph is graph, i.e., a set of objects (called vertices or nodes) that are connected together, where all the edges are bidirectional. An…

View On WordPress

#c data structures#c graph programs#connected components algorithm#connected components example#connected components of a graph#connected components of a graph example#connected components undirected graph algorithm#counting number of connected components in a undirected graph#number of connected components in an undirected graph#strongly connected components example#strongly connected components undirected graph#Undirected Graph

0 notes

Link

Have you ever solved a real-life maze? The approach that most of us take while solving a maze is that we follow a path until we reach a dead end, and then backtrack and retrace our steps to find another possible path. This is exactly the analogy of Depth First Search (DFS). It's a popular graph traversal algorithm that starts at the root node, and travels as far as it can down a given branch, then backtracks until it finds another unexplored path to explore. This approach is continued until all the nodes of the graph have been visited. In today’s tutorial, we are going to discover a DFS pattern that will be used to solve some of the important tree and graph questions for your next Tech Giant Interview! We will solve some Medium and Hard Leetcode problems using the same common technique. So, let’s get started, shall we?

Implementation

Since DFS has a recursive nature, it can be implemented using a stack. DFS Magic Spell:

Push a node to the stack

Pop the node

Retrieve unvisited neighbors of the removed node, push them to stack

Repeat steps 1, 2, and 3 as long as the stack is not empty

Graph Traversals

In general, there are 3 basic DFS traversals for binary trees:

Pre Order: Root, Left, Right OR Root, Right, Left

Post Order: Left, Right, Root OR Right, Left, Root

In order: Left, Root, Right OR Right, Root, Left

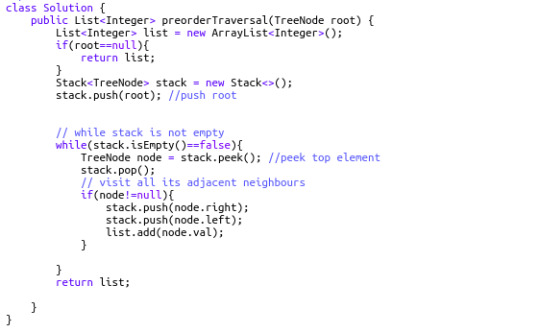

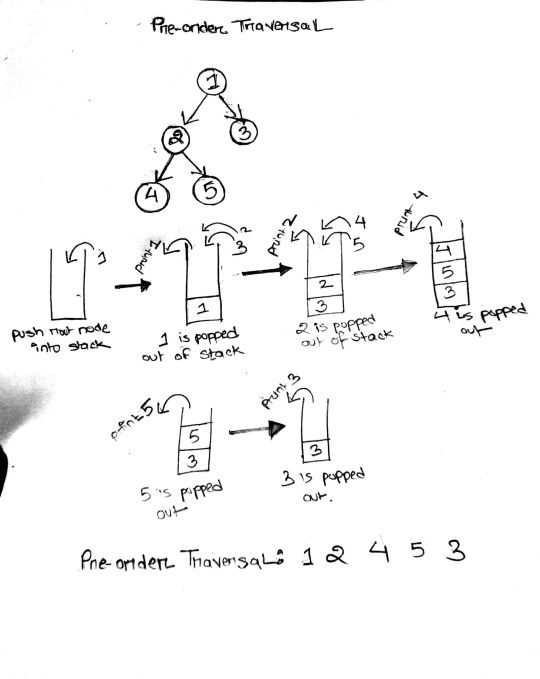

144. Binary Tree Preorder Traversal (Difficulty: Medium)

To solve this question all we need to do is simply recall our magic spell. Let's understand the simulation really well since this is the basic template we will be using to solve the rest of the problems.

At first, we push the root node into the stack. While the stack is not empty, we pop it, and push its right and left child into the stack. As we pop the root node, we immediately put it into our result list. Thus, the first element in the result list is the root (hence the name, Pre-order). The next element to be popped from the stack will be the top element of the stack right now: the left child of root node. The process is continued in a similar manner until the whole graph has been traversed and all the node values of the binary tree enter into the resulting list.

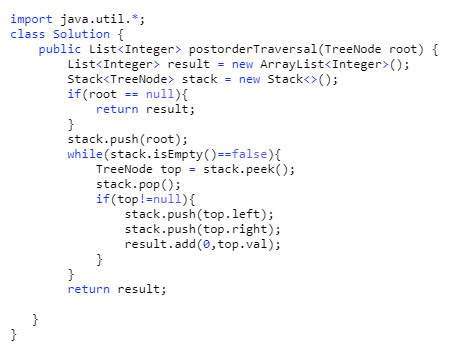

145. Binary Tree Postorder Traversal (Difficulty: Hard)

Pre-order traversal is root-left-right, and post-order is right-left-root. This means post order traversal is exactly the reverse of pre-order traversal. So one solution that might come to mind right now is simply reversing the resulting array of pre-order traversal. But think about it – that would cost O(n) time complexity to reverse it. A smarter solution is to copy and paste the exact code of the pre-order traversal, but put the result at the top of the linked list (index 0) at each iteration. It takes constant time to add an element to the head of a linked list. Cool, right?

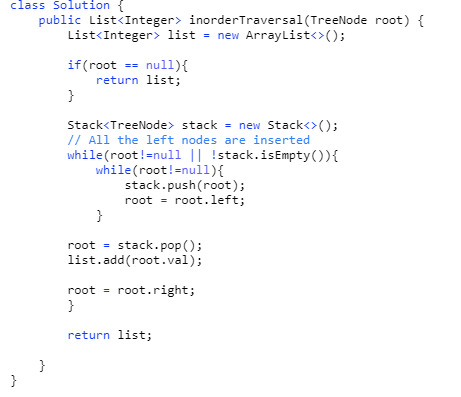

94. Binary Tree Inorder Traversal (Difficulty: Medium)

Our approach to solve this problem is similar to the previous problems. But here, we will visit everything on the left side of a node, print the node, and then visit everything on the right side of the node.

323. Number of Connected Components in an Undirected Graph (Difficulty: Medium)

Our approach here is to create a variable called ans that stores the number of connected components. First, we will initialize all vertices as unvisited. We will start from a node, and while carrying out DFS on that node (of course, using our magic spell), it will mark all the nodes connected to it as visited. The value of ans will be incremented by 1.

import java.util.ArrayList; import java.util.List; import java.util.Stack; public class NumberOfConnectedComponents { public static void main(String[] args){ int[][] edge = {{0,1}, {1,2},{3,4}}; int n = 5; System.out.println(connectedcount(n, edge)); } public static int connectedcount(int n, int[][] edges) { boolean[] visited = new boolean[n]; List[] adj = new List[n]; for(int i=0; i<adj.length; i++){ adj[i] = new ArrayList<Integer>(); } // create the adjacency list for(int[] e: edges){ int from = e[0]; int to = e[1]; adj[from].add(to); adj[to].add(from); } Stack<Integer> stack = new Stack<>(); int ans = 0; // ans = count of how many times DFS is carried out // this for loop through the entire graph for(int i = 0; i < n; i++){ // if a node is not visited if(!visited[i]){ ans++; //push it in the stack stack.push(i); while(!stack.empty()) { int current = stack.peek(); stack.pop(); //pop the node visited[current] = true; // mark the node as visited List<Integer> list1 = adj[current]; // push the connected components of the current node into stack for (int neighbours:list1) { if (!visited[neighbours]) { stack.push(neighbours); } } } } } return ans; } }

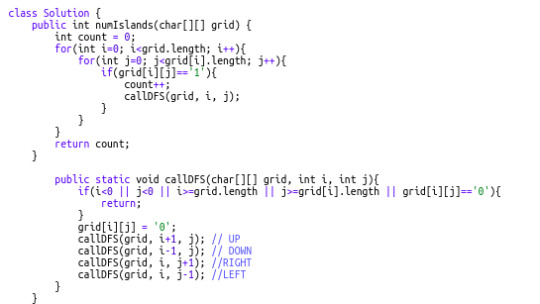

200. Number of Islands (Difficulty: Medium)

This falls under a general category of problems where we have to find the number of connected components, but the details are a bit tweaked. Instinctually, you might think that once we find a “1” we initiate a new component. We do a DFS from that cell in all 4 directions (up, down, right, left) and reach all 1’s connected to that cell. All these 1's connected to each other belong to the same group, and thus, our value of count is incremented by 1. We mark these cells of 1's as visited and move on to count other connected components.

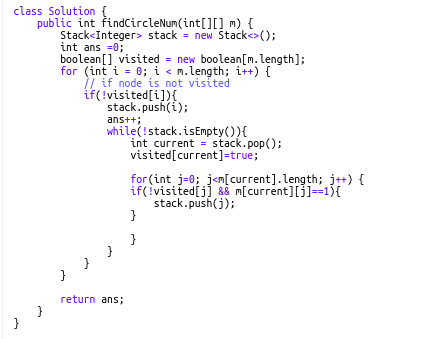

547. Friend Circles (Difficulty: Medium)

This also follows the same concept as finding the number of connected components. In this question, we have an NxN matrix but only N friends in total. Edges are directly given via the cells so we have to traverse a row to get the neighbors for a specific "friend". Notice that here, we use the same stack pattern as our previous problems.

That's all for today! I hope this has helped you understand DFS better and that you have enjoyed the tutorial. Please recommend this post if you think it may be useful for someone else!

0 notes

Text

Exercise 2: Coding Portion Solution

Exercise 2: Coding Portion Solution

This coding portion has three main parts:

Implement a function that efficiently counts the number of connected components in an undirected graph (modelled as a directed graph where both (u,v) and (v,u) directed edges are present for each undirected edge uv). (6 marks)

Implement a function that reads the data in a comma-separated values(CSV) file that describes a city’s road network and returns…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Exercise 2: Coding Portion Solution

Exercise 2: Coding Portion Solution

This coding portion has three main parts:

Implement a function that efficiently counts the number of connected components in an undirected graph (modelled as a directed graph where both (u,v) and (v,u) directed edges are present for each undirected edge uv). (6 marks)

Implement a function that reads the data in a comma-separated values(CSV) file that describes a city’s road network and returns…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Good Results Made Meaningless

Sometimes you see a beautiful theorem A that you love to talk about. Then another beautiful theorem B comes around, making the first one meaningless since B trivially implies A. Not just a mere extension of A but B had a completely different proof of something much stronger. People will forget all about A--why bother when you have B? Too bad because A was such a nice breakthrough in its time. Let me give two examples. In STOC 1995 Nisan and Ta-Shma showed that Symmetric logspace is closed under complement. Their proof worked quite differently from the 1988 Immerman-Szelepcsenyi nondeterministic logpsace closed under complement construction. Nisan and Ta-Shma created monotone circuits out of undirected graphs and used these monotone circuits to create sorting networks to count the number of connected components of the graph. Ten years later Omer Reingold showed that symmetric logspace was the same as deterministic logspace making the Nisan-Ta-Shma result an trivial corollary. Reingold's proof used walks on expander graphs and the Nisan-Ta-Shma construction was lost to history. In the late 80's we had several randomized algorithms for testing primality but they didn't usually give a proof that the number was prime. A nice result of Goldwasser and Kilian gave a way to randomly generate certified primes, primes with proofs of primeness. Adleman and Huang later showed that one can randomly find a proof of primeness for any prime. In 2002, Agrawal, Kayal and Saxena showed Primes in P, i.e., primes no longer needed a proof of primeness. As Joe Kilian said to me at the time, "there goes my best chance at a Gödel Prize". Computational Complexity published first on Computational Complexity

0 notes