#creditone

Text

Nightclubbing cat home after three months

New Post has been published on https://petnews2day.com/news/pet-news/cat-news/nightclubbing-cat-home-after-three-months/?utm_source=TR&utm_medium=Tumblr+%230&utm_campaign=social

Nightclubbing cat home after three months

Thursday, 11 April 2024 08:26 By Radio Exe News Teddie missing cat (image courtesy: Robyn Waring) Teddie turns up in Torquay A nightclubbing cat has been reunited with its owner three months after getting the hump because he was removed from a Torquay bar. Teddie, a one-year-old ginger tom, used to wear a collar saying […]

See full article at https://petnews2day.com/news/pet-news/cat-news/nightclubbing-cat-home-after-three-months/?utm_source=TR&utm_medium=Tumblr+%230&utm_campaign=social

#CatsNews #BayFm, #Crediton, #Dawlish, #Devon, #DigitalRadioDevon, #Exeter, #Exmouth, #HeartDevon, #HeartSouthWest, #Honiton, #LocalExeterRadio, #LocalRadio, #OtteryStMary, #Radio, #RadioDevon

#bay fm#crediton#dawlish#devon#digital radio devon#exeter#exmouth#heart devon#heart south west#honiton#local exeter radio#Local Radio#ottery st mary#radio#radio devon#Cats News

1 note

·

View note

Text

6th March

St Baldred’s Day/ Uncle Tom Cobbley And All

Old uncle Tom Cobley and all. Source: Devon Heritage’s postcard collection

On this day in 1794, Thomas Cobbley a prosperous yeoman from Crediton in Devon died. Cobbley was the inspiration for the drinking song Widdecombe Fair which tells the repetitive story of Cobbley and his mates piling onto an unfortunate grey mare to get to the fair. Perhaps the rhyme was knowing mockery of the local squire because Cobbley was a landowner who possessed several horses and had no need to borrow his steed from Tom Pearce. At least two of Cobbley’s gang are mentioned in church records, including Pearce, and Cobbley himself was buried in the churchyard at Sprayton where his grave can still be seen. Apparently Cobbley and his crew, including the long suffering mare, haunt the roads in and out of Widdecombe in eternal search of the fair, which still takes place every September.

Today is also St Baldred’s Day. Baldred’s most noteworthy feat was to remove a dangerous reef between Bass Rock and mainland Lothian by the power of prayer and deposit it on the coast near North Berwick where it still resides.

#uncle tom Cobbley and all#Widdecombe fair#Tom pearce’s grey mare#crediton#english folklore#sprayton#Devon#st baldred

0 notes

Text

Official Presentation Devon Piano Lessons

My goal as a teacher is to develop well-rounded musicians who are able to understand, play and enjoy a wide spectrum of music, including classical ,jazz, rock and pop.I aim to provide a friendly and approachable service, and I look forward to hearing from you soon.

07910 628505

#keyboard lessons devon#keyboard lessons tiverton#piano lessons crediton#piano lessons devon#piano lessons tiverton

0 notes

Text

Y'all know me.

I'm that one guy who looks at angst and goes: "Time to get memeifed b4 I pull out the edits."

[Creditonals: Cathedral of War memes.]

SPOILER WARNING FOR BOUND LORE!

[memes undercut - Ashril centric]

#I'll give yall these 4 as i have way too many bound memes i need to post at some point :“]#skybound#bound smp#bound smp meme#bound smp ashril#sherbertquake56#sherbverse

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saint Boniface

Saint Boniface (or in Dutch the Heilige Bonifatius) is one of the most famous saints in the Netherlands. His real name was Wynfreth and he lived from 672 until 754 CE. Pope Gregory II, who ruled from 715 to 731 CE, was at that time struggling with pagan Germanic tribes and, keen to convert them, Wynfreth offered Gregory the perfect opportunity to achieve this goal, the Christianization of Europe. After he received the name Boniface on the 5th of May 719 CE, which means 'he who does good', he served as a missionary in the first half of the 8th century and helped reorganize the church in Germany and the Frankish kingdom.

Early life

Boniface was born in southern England in the Essex region, probably near Exeter, and presumably Crediton. Descended from a noble family, from his earliest years he showed great ability and received a religious education. His parents intended him for secular pursuits, but, the young Wynfreth was inspired with higher ideals by missionary monks who visited his home. Consequently, he was, according to Celtic and Anglo-Saxon tradition, taken in at the monastery of Adescancastre. Such children as these were known as pueri oblate and in the monastery the children learned to read and write and became familiar with Roman civilisation. Even at this early age the young Wynfreth was both intelligent and eager to learn.

Continue reading...

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Südengland / Cornwall 2024 - Tag 15

Ladies and Gentlemen!

Heute verlassen wir auch schon wieder unser Farmcottage in Dorset. Die Zeit vergeht wieder einmal, wie im Flug.

Und so machen wir uns nach dem Frühstück auf, um heute unsere westlichste und finale Destination zu erreichen ...

Doch bevor es soweit ist, fahren wir erst einmal ins sagenumwobene Dartmoor. Das erreichen wir schon kurz hinter Exeter. Das wilde Moorland erstreckt sich über eine Fläche von 954 Quadratkilometer und hat neben viel unberührt scheinender Natur nur sehr wenig Menschen.

Erster Programmpunkt heute ist die Whisky Brennerei in Bovey Tracey. Die Destillerie trägt den bezeichnenden Namen "Dartmoor Whisky" und war bis vor Kurzem die einzige Whiskybrennerei der Grafschaft.

Die Brennerei wurde von Greg Millar gegründet und 2019 offiziell eröffnet.

Die Brennerei produziert mit einer ehemaligen Cognac-Destille aus dem Jahr 1966, die 2014 aus Frankreich her transportiert wurde. Der Brennmeister ist Frank McHardy, der zuvor für Springbank und Bushmills arbeitete.

Das Volumen wird, für die Pot Still, mit 1.400 Litern angeben. Die benötigte Gerste wird von der Preston Farm in Dartmoor bezogen, gemälzt wird in den Tuckers Maltings, unweit der Brennerei – der Whisky der Dartmoor Distillery ist also ein sehr regionales Produkt.

Dartmoor bietet drei Kernabfüllungen an. Dies sind das Bourbon Cask , Sherry Cask und Bordeux Wine Cask.

Der Shop befindet sich an der rückwärtigen Seite und wir müssen erst einmal klingeln, um Einlass zu bekommen, da wir hier ohne vorherige Terminvereinbarung aufschlagen.

Das ist aber alles überhaupt kein Problem, man gewährt uns Einlass und freut sich über unseren Besuch. Wir erfahren wieder neue Dinge, beispielsweise warum hier die Gerste nicht mit Torf gemälzt wird, wo doch reichlich Torf vorhanden ist. Des Rätsels Lösung: das Abbauen von Torf ist im Nationalpark unter Strafe verboten.

Man schwätzt angeregt mit uns und erklärt alles, bis die nächsten Kunden kommen - unser Signal für den diskreten Rückzug.

Wir fahren weiter, immer tiefer in das Dartmoor hinein. Die Landschaft ist von bizarrer Schönheit und gut versteckt finden sich zwischendurch hübsche kleine Ortschaften.

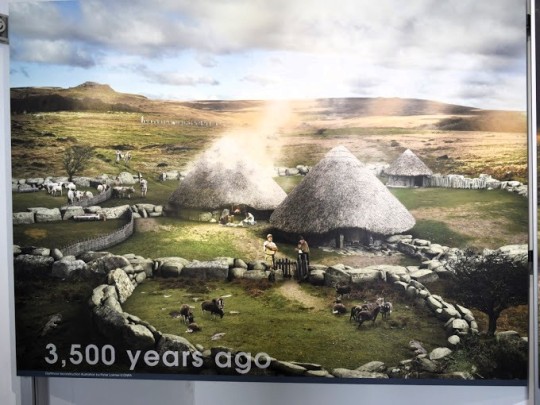

Als die ersten Siedler in der Jungsteinzeit in die Gegend des heutigen Moorlandes kamen, gab es hier einen großen Wald. Die Siedler rodeten die Bäume und wurden sesshaft. Da der Boden jedoch für den Ackerbau kaum geeignet war, betrieben sie hier hauptsächlich Viehzucht.

Ein plötzlicher Klimawandel führte dann dazu, dass die frühen Bauern das Dartmoor schon nach wenigen Jahrtausenden wieder verließen. Bis heute hat sich das Gesicht dieser Landschaft kaum mehr verändert, sodass es nicht einmal viel Phantasie braucht, um sich vorzustellen, wie das Land vor etwa 3.000 Jahren ausgesehen hat.

Wer durch das Moorland mäandert, kann auch noch überall die Zeugnisse der frühen Besiedlung des Dartmoors finden. Das zieht natürlich Archäologen an. Bei einer der Ausgrabungen wurden in den 1970er Jahren auch Hufabdrücke gefunden. Sie beweisen: Im Dartmoor gab es bereits in der Bronzezeit – also vor 3.500 Jahren – Pferde/Ponys.

Die Dartmoor Ponys sind somit eine der ältesten Ponyrassen – und doch gelten sie heute als gefährdet. Weltweit soll es gerade mal noch 3.000 Ponys geben.

Die offizielle Geschichte vom Dartmoor Pony beginnt allerdings erst im Jahr 1012 nach Christus. Genauer: Mit einem Testament. Denn im letzten Willen von Bischof Aelwold von Crediton erwähnte er auch seine Ponys. Sie waren nicht eingeritten und lebten wild im Dartmoor.

Doch im Laufe der Jahrhunderte erkannten die Menschen, wie nützlich die „Kleinen“ sind. Zwischen dem zwölften und 15. Jahrhundert wurden die Ponys zum Beispiel genutzt, um Zinn vom Moor in die Städte zu transportieren. Als der Zinn-Boom zu Ende ging, blieben vermutlich einige dieser Ponys übrig. Sie zogen durchs Moor – oder wurden von den Bauern als kleine Lastpferde eingesetzt.

König Heinrich der VIII. war nicht nur für seine sechs Ehefrauen berüchtigt, er mochte auch keine Ponys. Demnach sollten alle Hengste unter 1,42 Metern und alle Stuten unter 1,31 Metern getötet werden. Das traf das ganze Land. Doch die Menschen im Dartmoor ließen sich nicht beeindrucken. Sie brauchten die kleinen, robusten Ponys – und so überlebten die „Kleinen“.

Während der Kriege waren die Kleinen über die Jahrhunderte nicht interessant: Durch ihre Größe waren sie im Kampf eher ungeeignet. Doch das änderte sich mit der industriellen Revolution um 1750. Jetzt waren die zähen und robusten Ponys plötzlich heiß begehrt – für die Bergwerke. Dort lebten sie unter Tage und zogen die schweren Loren.

Auch heute übernehmen die Pferdchen wichtige Aufgaben: als Landschaftspfleger. Denn die Kleinen haben einen Vorteil: Mit ihren etwas mehr als 200 Kilogramm sind sie Pferde-Leichtgewichte und hinterlassen auch in sensiblen Naturschutzgebieten kaum Spuren. Sie werden durch ihre Trittsicherheit auch auf steilen Flächen eingesetzt.

Wie wichtig die Kleinen in ihrer Heimat heute sind, wurde 1951 klar: Damals wurde das Dartmoor zum Nationalpark erklärt – und das Pony als Logo ausgewählt.

Neben alten Siedlungen finden sich auch Steinkreise und Steinreihen - und so ist das Dartmoor von vielen Mythen und Legenden umwoben, die auch noch heute vielerorts erzählt werden.

Die Landschaft selbst bietet schon ausreichend Kulisse für Schauergeschichten jeglicher Art.

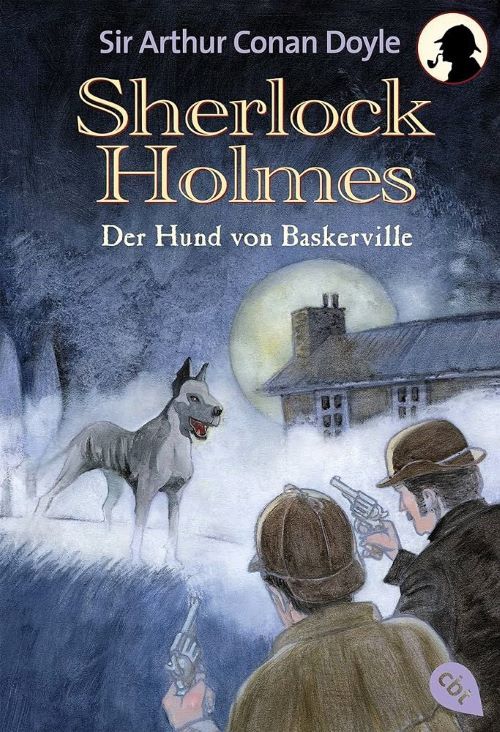

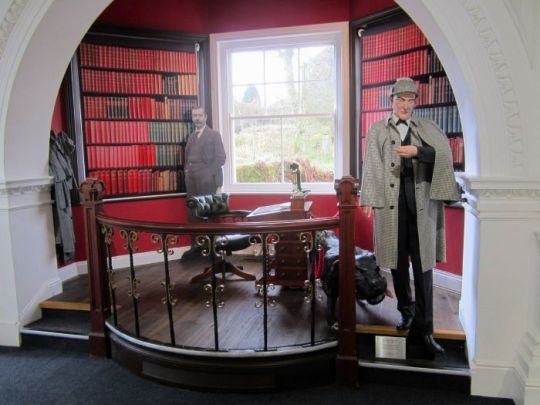

Um 1900 war es zum Beispiel die Legende von Richard Capel von Brooke Manor, der die Töchter seiner Pächter entführt und vergewaltigt haben soll, die Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, der mit den Sherlock Holmes -Romanen berühmt geworden ist, zu seinem Roman „Der Hund von Baskervilles“ inspiriert hat.

Die Legende von Richard Chapel, der 1677 von einem Rudel dämonischer Hunde zu Tode gehetzt worden sein soll, wurde von Generation zu Generation im Dartmoor weiter erzählt. Doyle griff sie auf und erzählte die Geschichte eines Geisterhundes, der durch die Untaten eines bösartigen Vorfahren erweckt wurde und nun sein Unwesen in den einsamen Hochebenen des Moorlandes treibt.

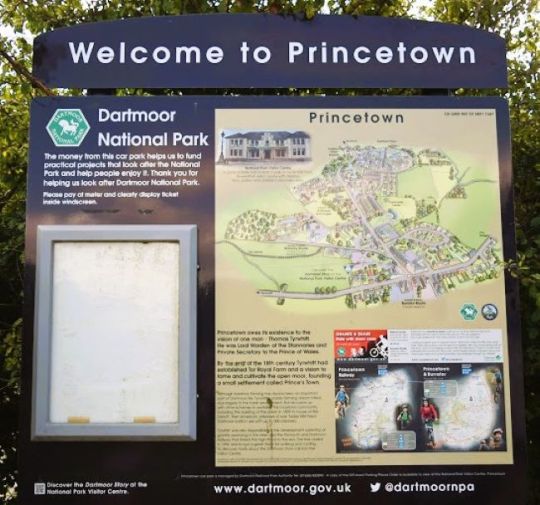

Unsere Mittagspause verbringen wir in dem 1785 gegründeten Städtchen Princetown, benannt nach dem damaligen Prince of Wales (heute Prince William).

Princetown ist das Verwaltungszentrum des Dartmoor-Nationalparks und die höchstgelegene Stadt im Dartmoor.

Über dem Ort Princetown erhebt sich das berüchtigte Dartmoor Prison, welches ebenfalls schon eine Rolle in Arthur Conan Doyles „Der Hund von Baskerville“ gespielt hat. Na, da sind wir doch goldrichtig!

Das Gefängnis wurde ursprünglich zur Unterbringung französischer Kriegsgefangener während der Napoleonischen Kriege gebaut. Im Krieg mit Frankreich gemachte Gefangene wurden zunächst in Gefängniskolonnen untergebracht; unter anderem auf verfallenen Schiffen.

Die Lebensbedingungen waren schrecklich und die Nähe der Gefängniskolonien zu den Werften von Plymouth wurde als Sicherheitsrisiko angesehen. Im Jahr 1806 wurde im abgelegenen Moorgebiet von Dartmoor, mit dem Bau eines eigens dafür errichteten Gefängnisses begonnen.

Das Gefängnisgelände wurde vom Prinzen von Wales zur Verfügung gestellt und ist rechtlich immer noch Eigentum des Herzogtums Cornwall, das dem jetzigen Prinzen William gehört.

Die ersten französischen Gefangenen kamen 1809 hierher, und im Krieg von 1812 gesellten sich schnell Amerikaner hinzu. Auf seinem Höhepunkt befanden sich im Gefängnis über 8.000 Insassen.

Nach dem Ende beider Konflikte blieb das Gefängnis bis 1850 ungenutzt, dann wurde es als Sträflingsgefängnis und später als Gefängnisfarm genutzt.

1917 wurde es in ein Arbeitszentrum für Kriegsdienstverweigerer umgewandelt und 1920 wieder als Gefängnis in Betrieb genommen.

Natürlich gibt bzw. gab es auch eine Polizeistation, die im Jahr 1856 eröffnet wurde und 1958, rund 100 Jahre später, wieder geschlossen wurde.

The Old Police Station wurde in ein Café umgebaut - ein Gastronomiebetrieb genau nach unserem Geschmack: skurril und historisch.

Wenn man genau hinschaut entdeckt man auch noch Relikte der ursprünglichen Nutzung des Gebäudes: Rechts, vom jetzigen Eingang und der Veranda, gibt es ein Fenster. Die Fensterbank und der Sturz weisen eine Reihe von sechs regelmäßigen und passenden Löchern, die auf das frühere Vorhandensein von Gittern hinweisen, auf.

Das Ambiente ist rustikal und es kommen sehr viele Locals zum Lunch. Das ist immer ein gutes Zeichen - und richtig! Das Essen ist gute, preiswerte Hausmannskost und der Service super flott! Eine klare Empfehlung, die wir gerne weiter geben.

Als wir den Wagen auf dem öffentlichen Parkplatz oberhalb der Gaststätte parken, fällt uns ein bekannter Geruch auf: Whisky! Irgendwo gibt´s hier Whisky!

Und richtig! In Princetown gibt es eine ziemlich neue Distillery: die mit der Produktion gerade erst begonnen hat. Man kann aktuell nur ganze Fässer, die bereits zur Reifung abgefüllt wurden, kaufen.

Flaschen gibt es zur Zeit noch nicht, da die Fassreife noch nicht abgeschlossen ist.

Das Grundstück, auf dem die neue Brennerei erbaut wurde, gehört dem Herzog von Cornwall. Das war zu Baubeginn Prinz Charles und nach aktueller Thronfolge ist es Prinz William.

Selbstverständlich haben wir uns zwischenzeitlich auch die Homepage angeschaut. Wie wir finden, wird die Lage nur minimal beschönigt.

Aber seht selbst: hier die raue Wirklichkeit ...

... und hier die leicht romantisierte Version:

Der Unterschied ist doch kaum wahrnehmbar - oder?

Nach der Mittagspause machen wir uns wieder auf den Weg, um die letzten 2 1/2 Stunden zu unserer Unterkunft in St Keverne in Cornwall zu bewältigen.

Gegen 18 Uhr erreichen wir unser Cottage auf The Lizard, dem östlichen Flügel Cornwalls.

Good Night!

Angie, Micha und Mister Bunnybear

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

#activatefirstpremierbankcreditcard#bestcreditcards#CreditCards#firstpremier#firstpremierbank#firstpremierbankcard#firstpremierbankcreditcardreview#firstpremierbanklogin#firstpremierbankmastercard#firstpremierbankmastercardcreditcard#firstpremierbankmastercardreviews#firstpremiercard#firstpremiercreditcard#firstpremiercreditcardreview#firstpremiermastercard#firstpremiere

0 notes

Text

The English Apple 🍎 Is Disappearing

As The Country Loses Its Local Cultivars, an Orchard Owner and a Group of Biologists are Working to Record and Map Every Variety of Apple Tree They Can Find in the West of England.

— By Sam Knight | May 4, 2024

Illustration By Nicholas Konrad/The New Yorker

In June, 1899, Sabine Baring-Gould, an English rector, collector of folk songs, and author of a truly prodigious quantity of prose, was putting the finishing touches on “A Book of the West,” a two-volume study of Devon and Cornwall. Baring-Gould, who had fifteen children and kept a tame bat, wrote more than a thousand literary works, including some thirty novels, a biography of Napoleon, and an influential study of werewolves. In the preface to his latest, he wrote that it was neither a guide book nor a history of the counties, which would have made it too heavy to carry. Instead, Baring-Gould had chosen to “pick out some incident, or some biography” to elucidate the places that he described. The town of Honiton was notable for its lace; Torquay for its caves; Tiverton for Old Snow, a kindly male witch who had died a few years earlier.

Baring-Gould devoted thirteen pages of his description of Crediton, a “curious, sleepy place” on the banks of the river Creedy, in the heart of Devon, to its apples. For months of the year, the town was awash in fruit and cider. The soil all around was red. In the orchards, trees were heavy with everything from “griggles” (small, stunted apples left over for children) to storied cider-making varieties, such as Kingston Black and Cherry Pearmain. In the fall, Baring-Gould wrote, “The grass of the orchard is bright with crimson and gold as though it were studded with jewels.” Life in the Creedy valley was dense with ancient apple lore, such as “S. Frankin’s Days,” in May, when the Devil might bring a late frost; the firing of blank charges into the bare branches of apple trees on Old Christmas Day, to bring good luck; and “wassailing” the trees, or singing to their health. There had been tough times for apple growers earlier in the century, with the rise of beer and imports from America. But those threats were on the wane. “The trees are having their good times again,” Baring-Gould wrote.

The Trees Are Not Having Good Times Now. On a blustery morning a few weeks ago, I drove to Crediton to visit Sandford Orchards, the largest remaining cider mill in town. The factory was cut into the side of a steep hill so that it could stay cool all year round. One of its oak vats, the General, dates from 1903 and holds ten thousand gallons of fermenting apple juice. When I arrived, the proprietor, Barny Butterfield, was in conversation with a colleague about the flavor profile of the latest batch of Devon Dry, one of the company’s ciders. “There’s no recipe!” Butterfield told me, a little giddily.

Butterfield reopened the ciderworks in 2014. (The original occupant, Creedy Valley Cider, closed in 1967.) Since then, he has become a prominent—and occasionally isolated—advocate for Britain’s encyclopedic variety of apples, of which there are more than two and a half thousand cultivars. The Romans, most likely, brought the first rootstocks. The Saxons inscribed the fruit into land and myth. (Avalon, the Arthurian paradise, means “land of apples.”) The Victorians went melanzane for them. (“Melanzana,” Italian for “eggplant,” comes from “mala insana,” or “mad apple.”) Apples are now the national fruit. But the British apple industry is deep in crisis. Most people agree that the market, which divides into dessert—or eating—apples and cider apples, is broken in one way or another. Butterfield, who is forty-seven, took me upstairs to his office, which was dotted with old stoneware jugs and scientific papers from the nineteen-fifties detailing the juice composition of cider-apple varieties, and sat down at his desk. “We’re going into the crater,” he said.

When Baring-Gould wrote about Crediton, Devon had twenty-six thousand acres of apple orchards. Ninety per cent of those are thought to be gone. And the growers who are left are losing money fast. According to British Apples & Pears Limited (B.A.P.L.), a trade organization that represents three hundred apple and pear farmers in the country, the cost of producing apples in the U.K. has increased by thirty per cent since 2021—an uptick driven mainly by rising energy prices and labor costs. During the same period, retail prices have risen by only a quarter of that. “So there’s a big gap,” Ali Capper, the executive chair of B.A.P.L., told me last week. “Mind the gap, I’ve started to say.”

Capper grows cider and dessert apples overlooking the Malvern Hills, by the border between Worcestershire and Herefordshire. She said that the cost of producing a pack of six Gala apples, a cultivar first developed in New Zealand in the nineteen-thirties, which is one of Britain’s most popular apples, was currently one pound and six pence. But the supermarkets weren’t paying that. “I would be surprised if there’s any retailer in the U.K that is paying a pound,” Capper said.

The British grocery market is an oligopoly. Eight retailers control ninety-two per cent of sales. A recent report by the House of Lords Horticultural Sector Committee described their power as “behemothic.” They can source cold-stored Galas from all over the world. (About sixty per cent of apples sold in the U.K. are imported.) For cultural, possibly griggle-related, reasons, British consumers like a small apple, one that fits easily in the hand. The U.S. and Asian markets prefer larger fruit, so foreign farmers can often sell smaller apples that have been rejected by their own retailers to British grocers at a discount. “It’s very difficult to compete with that,” Capper said.

The combination of steeply rising costs and being undercut by cheaper, similar apples from overseas is proving unmanageable. “It’s happened very quickly,” Capper told me. “We’ve had businesses going from profitable and able to cope with volatility to losing money.” As a rule, British apple growers tend to plant between eight hundred thousand and a million and a half new trees each year to refresh their orchards and keep up with changing tastes. In recent years, the total has been closer to four hundred thousand. “If you don’t reinvest as a sector, you don’t stay with the market,” Capper said. “And if you can’t stay with the market, then you go out of business.” Last fall, a survey of a hundred fruit and vegetable farmers found that forty-nine were expecting to go bankrupt in the next twelve months.

While all British apple growers are suffering, they don’t see the crisis the same way. Capper struck me as phlegmatic about the power of the supermarkets. “Loyalty is gone,” she said. “It’s all about buying cheap.” She was also unsentimental about the rise of generic, global apple varieties—often characterized by white flesh, a crisp bite, and an ability to store well, or hold their “pressures,” for months at a time—many of which have been developed by apple breeders in Australasia. The tastiest apple at Britain’s National Fruit Show for eight of the past ten years has been the Jazz, the marketing name for the Scifresh cultivar—a cross between Gala and Braeburn, two New Zealand varieties—which was first developed in 1985.

Capper told me that the sector was going through a moment comparable to one it experienced in the late seventies, when French farmers started exporting the Golden Delicious to the U.K. under the slogan “Le Crunch.” “It nearly killed the British industry,” she said. “There was obviously the loss of an awful lot of orchards. And then what happened was that there was a refocus by the industry on varieties that could compete.” Of the twenty-five or so varieties of eating apple now grown commercially in Britain, only nine originated here. “There is a lot of hand-wringing about that,” Capper said. “But the truth is that those traditional varieties were actually very hard to grow.” Yields were unpredictable and shelf lives short. Between 2015 and 2020, the annual crop of Cox’s Orange Pippin—the sharp, tangy taste of English autumns since it first went on sale in the eighteen-fifties—fell by more than fifty per cent.

For Butterfield, this is a counsel of despair. “The Cox, the Egremont Russet,” he said, with feeling, referring to a rusty-looking but delicious apple raised on the estate of the Earl of Egremont, in Petworth, in the late nineteenth century. “I mean, the Egremont Russet—what a fucking apple.” In his view, global supply chains and a few standardized cultivars have separated Britain’s population from the apple of its eye. “One of the problems that we’ve got is, What are we saving? We’re saving dreary red fruit that tastes of absolute nothing,” Butterfield told me. “There’s nothing to say. If you could put an Egremont Russet back into someone’s hands—put it back into their lunchbox—for a moment they are transported, because the amount of flavor and richness, you could get excited about that. . . . The problem is that the great British public are not exposed to this.”

To remind us of what was here, Butterfield and a group of biologists at the University of Bristol have been working to record and map every variety of apple tree they can find in the West of England. The project started in 2017, when Liz Copas—the last pomologist at the Long Ashton Research Station, a now defunct government fruit-and-cider research institute—revealed that the breeding records of a group of novel cider-apple cultivars known as the Girls had been lost. Three crop scientists—Keith Edwards, Amanda Burridge, and Mark Winfield—adapted a form of DNA technology, which they had used to identify different strains of wheat, to take a genomic “fingerprint” from the Girls’ leaves.

Since then, the apple-tree database has grown to incorporate every cultivar held in the National Fruit Collection, at Brogdale, in Kent, and hundreds more, from the West Country. When Edwards and I met, he told me, “I worry about these kinds of interviews because one of the things it does is initiate an avalanche of e-mails from people who have an interesting apple tree in their garden.” In 2020, he and the team received around eight hundred tree samples—including entire branches—at their laboratory in Bristol. “The majority of them were Cox’s or Bramleys,” Edwards said. (Bramleys are the country’s best-loved cooking apples.) “That’s fine.”

In his office in Crediton, Butterfield pulled up the database on his computer and started reading off the local varieties, most of them cider-apple trees, many of which he had sampled, logged, and pruned himself: “Harvest Lemon, Reinette d’Obry, Michelin, Chisel Jersey, Crimson Newton, Tremlett’s Bitter, Crimson King, Fair Maid of Devon, Tan Harvey.” Every chance seedling—a core thrown from a car window—has its own DNA and is highly unlikely to produce decent apples. But cultivars, which have been selected at one time or another for their fruit, yield, or hardiness, are clones. (Apple-tree grafting was established by the time of Alexander the Great.) The trees that Butterfield and the crop scientists are most interested in are lost cultivars, occasional trees with matching DNA, whose potential was once seen but is now forgotten. “Group 1, Group 7, Group 15,” Butterfield read out. “These are unique. They’re in no collection anywhere.” He went on, “But they’re in Cross Barton, and they’re in Uppincott, and then they’re in Whiteways.” Whiteways, fifteen miles east of Butterfield’s ciderworks, was once the largest apple orchard in the world.

Butterfield blends the juices of between forty to seventy apple varieties to make his ciders. He dreams of finding a lost cultivar that will top them all. “Where are these shit-hot, really interesting apples that are gonna make great drinks?” he said. In the seventeen-twenties, the fruit of a single tree, named Royal Wilding, which grew next to the old port road to Exeter, was the talk of the county. There is no known surviving graft. Butterfield is also on the hunt for what he calls “natural survivors.” Climate change is altering Britain’s apple harvests. The Dabinett, the mainstay of the cider-apple crop, requires cold winters, especially as a young tree, in order to flower properly in the spring—a process known as vernalization. But frost and snow are becoming ever rarer in the U.K. (Butterfield’s best-performing orchard is in a north-facing valley.) The industry will need to find a successor apple—to go back to its library of cultivars—at some point. “We have funnelled our genetics . . . we have picked favorites,” Butterfield said. “If we don’t keep the broader, ancient DNA in existence, then it’s gone.”

The real spirit of the project is both nostalgic and utopian. The records of costermongers (originally apple sellers) from the nineteenth century show that English apples were sold from September to May, without chemicals or cold storage or cargo ships to carry them around the world. “What fucking apples were they, that weren’t stored in a giant refrigerator and gassed?” Butterfield said. He told me about Ironsides, which became soft enough to eat only after Christmas, after a few months in a cellar, and were edible all year round. Perhaps there is a future in which local, low-carbon farming and centuries of apple-growing knowledge become necessary, or even desirable, again. Perhaps there isn’t. Just in case, Butterfield wants supermarkets to consider devoting ten per cent of their apples to “heritage varieties,” to give the country’s traditional cultivars a chance. “They’re never going to agree to anything that moves the dial,” he acknowledged. “But if we can keep these apples alive and remind ourselves . . .”

A couple of weeks after I visited Crediton, I called Duncan Small, who has helped run Charlton Orchards in the village of Creech St. Michael, in Somerset, for the past thirty-five years. Small specializes in growing traditional English varieties, including Ashmead’s Kernel. “It looks rough, quite frankly. It often has cracks in it,” Small told me. “Not particularly appealing to the eye, but an absolutely delicious apple. Yeah. Really good. Quite popular during Victorian times.” Small is sixty-four. He and his wife, Sally, are closing the orchard. “It’s not viable anymore, unfortunately,” he said. Small was not sure that the wider public cared about English apples anymore. “I don’t think enough people think about it, more than just having a crunch and chuck it over their shoulder,” he said. “Where it comes from doesn’t really worry them.”

It has been a cold spring, but the first apple blossoms have started to appear. I asked Small if he enjoyed this time of year and he said that these were probably the most stressful weeks in the orchard. A late frost, or not enough pollinators, could wreck the harvest. Then he started talking about his father, Robin, who used to tend the trees before him. During cold, clear nights in the spring, when he feared a frost, or when the wind got up, in the fall, and the boughs were full of fruit, Small’s father would be too anxious to stay in the house. “He just couldn’t rest. He’d just have to be out,” Small said. His father would walk up and down among the trees in the dark. “He couldn’t do anything. But he just felt that if the apples were out there being exposed to it, he ought to be as well,” Small recalled. “So he’d go out and torture himself.” ♦

#UK 🇬🇧#England 🏴#Farmers#Apples 🍎 🍏#Disappearance | English Apple 🍏 🍎#Country | Loses | Local Cultivators#Biologists#Mapping | Every Variety | West of England 🏴#Sam Knight | The New Yorker

0 notes

Text

Colebrooke Fete and Fun Dog Show on Saturday - Crediton Courier

New Post has been published on https://petn.ws/ZjG1W

Colebrooke Fete and Fun Dog Show on Saturday - Crediton Courier

Colebrooke Fete and Fun Dog Show on Saturday Crediton Courier

See full article at https://petn.ws/ZjG1W

#DogNews

0 notes

Text

THE FOREFATHER OF AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

Marcos Rodrigues

MA in Ethnic and African Studies, UFBA

ORCID: 0000 0002-6662-2350

Review of GLEDHILL, Sabrina (ed.). Manuel Querino (1851-1923): An Afro-Brazilian Pioneer in the Age of Scientific Racism. Crediton: Funmilayo, 2021.[1]

Edited by the independent scholar Sabrina Gledhill, this book introduces—or reintroduces—the life and work of the Brazilian intellectual and activist Manuel…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Northwood cider apples in the evening sun. A West Country cider apple from Crediton area, Devon 18th C

Soft sweet and fruity cider. #cider

0 notes

Text

Credit One Credit Card #creditone #creditboost #creditkarma

MARCEDRIC KIRBY FOUNDER CEO.

MARCEDRIC.KIRBY INC.

THE VALLEY OF THE VAMPIRES

0 notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: CB Sports 3 Snap Pullover Womens Purple Navy CreditOne Charleston Open Size L.

0 notes

Text

https://c1b.page.link/p95MAJUU8GMfVMbm6

Apply for a “CreditOne” Bank Card

0 notes

Text

"File:2016 Tour of Britain (6) Crediton - Team Sky.jpg" by Geof Sheppard is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

#skinsuit#lycra bulge#lycra#bibshorts#cycling bulge#guys in lycra#skintight#beardsandtattoos#bib shorts#lycra spandex#spandex

0 notes