#davout's country home

Text

Random AU story idea I woke up with:

1815: In the immediate aftermath of Waterloo, both Ney and Soult find themselves running from the "White terror". They end up together and on foot, trying to reach the Tarn (Soult's home, where he feels people would protect him). Despite their mutual dislike they need to work together, especially when the exertion causes Soult's bad leg to worsen to the point he can barely walk...

Having reached Saint-Amans, they hide with Mama Soult. When King Louis XVIII exiles Soult and condemns Ney to death (in absence), Louise Soult in Paris (with help from Davout and Aimée?) needs to organize a way for Ney to be smuggled out of the country. Not that she's usually very fond of Aglaé Ney, mind you...

So Ney will find himself as a "guest" to the Soult family in Düsseldorf in 1816, instead of in front of a firing squad, and wondering if he really picked the better deal.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Countess Potocka Visits the Davouts

The moment is drawing near when I will say goodbye to Countess Potocka. In my next post she will share the scene with another memoir-writer, both of them describing the same person in quite contrasting ways. For now, the Countess is still starring on her own, compelled by good manners to accept an invitation to a meal she would have given her left arm to be able to refuse. Marie-Louise being absent, the Countess finds another handy target for her barbs.

The Countess, having ascertained whether her visit will be more convenient in the daytime or in the evening (daytime), gets dressed in new, fashionable and expensive attire, though she is much bothered by her shoes (too small?). I can't help but think that this outfit was meant to impress the Davouts with her superior status and unimpeachable pedigree - something simpler would have been preferable, as we shall see. Since it's already three in the afternoon when she appears at her hosts' door, maybe they were not expecting her anymore, even if we assume she had advised them this was the day of her visit. At least the Countess is honest enough to state Madame Davout had treated her well in the past.

C'est ainsi que j'allai chez la maréchale Davout, qui m'avait comblée de prévenances pendant son séjour à Varsovie, du temps où son mari commandait en Pologne. Comme elle passait les étés à Savigny (1), c'est là qu'il fallut aller la chercher. J'envoyai à son hôtel en ville quelle serait l'heure la plus convenable pour faire ma visite, - on me répondit que ce serait dans la matinée. Je me rendis donc à Savigny par un soleil brûlant, mal garantie par un très petit chapeau orné de violettes, et très gênée dans mes brodequins lilas parfaitement assortis à une robe montante en gros de Naples de même couleur ; - madame Germont, oracle de la mode, avait elle-même combiné toute ma toilette.

[...]

[J]e me promettais une visite agréable. L'hôtel de la maréchale, à Paris, m'avait donné une grande idée de son goût et de son opulence, et je pensais la trouver luxueusement établie à Savigny. J'arrivai vers trois heures. Le château, entouré d'un fossé et d'un mur, avait pour entrée une porte hermétiquement fermée. L'herbe croissait dans les fossés ; - on eût dit une habitation abandonnée depuis maintes années. Mon laquais, ayant enfin trouvé le cordon de la sonnette, une petite fille assez mal vêtue vint, au bout de quelques minutes, demander ce qu'on désirait.

- Madame la maréchale est-elle à la maison?

- Oh ! pardonnez-moi, qu'ils y sont, et M. le maréchal aussi, répondit la fillette.

Et vite elle accourut appeler un des hommes du château, qui se mit à la suivre sans se presser et tout en ajustant sa livrée.

Je me fis annoncer, et blottie dans la voiture, j'attendis encore assez longtemps, ne sachant trop si je devais insister ou simplement laisser une carte.

Au bout d'un petit quart d'heure un valet de chambre se présenta enfin à la portière du carrosse et me fit entrer dans une vaste cour ; il s'excusa des lenteurs du service, m'avouant sans façons qu'à l'instant où j'étais arrivée, les gens travaillaient au jardin, et que lui-même était occupé à nettoyer le verger.

On me fit traverser plusieurs salons complètement démeublés ; la pièce où l'on m'introduisit n'était guère plus ornée que les précédentes, mais au moins il y avait un canapé et des chaises ! La maréchale ne tarda pas à apparaître. Je m'aperçus aisément qu'elle avait fait toilette pour moi, car elle attachait encore quelques épingles à son corsage. Après quelques minutes d'une conversation languissante, elle sonna pour faire prévenir son mari. Puis nous reprîmes notre entretien pénible. Ce n'est pas que madame Davout manquât d'usage ou fût dépourvue de cette sorte d'esprit qui facilite les rapports entre deux personnes du même monde, mais il y avait en elle une certaine roideur qui pouvait être prise pour de la morgue. Elle ne perdait jamais de vue le maréchalat ; jamais un sourire gracieux ne venait animer les traits de sa beauté sévère. [...]

Le maréchal arriva enfin dans un état de transpiration qui attestait son empressement ; il s'assit tout essoufflé, et, tenant son mouchoir de poche pour s'essuyer le front, il eut soin de le mouiller de salive afin d'enlever plus sûrement la poussière dont sa figure était couverte. Cet abandon un peu soldatesque cadrait mal avec les manières empesées de son épouse ; elle en fut visiblement contrariée. Me trouvant de trop dans cette scène muette, je me levai et voulus prendre congé, mais on me pria de rester à déjeuner. En attendant que le repas fût servi, nous fîmes une promenade dans le parc... Il n'y avait aucun chemin tracé, les gazons étaient de hautes herbes toutes prêtes à devenir des meules de foin, les arbres coupés pendant la Révolution repoussaient en manière de broussaille ; je laissais à chaque buisson des fragments de mes volants, et mes brodequins lilas avaient pris une teinte verdâtre. Le maréchal nous encourageait de la voix et du geste, nous promettant une surprise charmante !... Quel ne fut pas mon désappointement lorsque, au détour d'un massif de chênes adolescents, nous nous trouvâmes en face de trois petites huttes en osier ! Le duc mit un genou en terre et s'écria :

- Ah! les voilà... les voilà !...

Puis, modulant sa voix :

- Pi... pi... pi...

Aussitôt une nuée de perdreaux se mit à voltiger autour de la tête du maréchal.

- Ne laissez sortir les autres qu'au moment où les plus jeunes seront rentrés, et donnez du pain à ces dames... Elles vont s'amuser comme des reines, dit-il à un rustre qui remplissait les fonctions de garde-chasse.

Et nous voilà, par un soleil brûlant, donnant la becquée aux perdreaux !

La duchesse vida, avec un calme et une dignité imperturbable, le panier qu'on lui avait présenté. Quant à moi, je faillis me trouver mal, et, n'y tenant plus, je fis observer que le ciel se couvrait et que nous étions menacés d'un orage.

[...]

Le déjeuner fini, je m'esquivai en toute hâte, jurant, mais un peu tard, qu'on ne m'y prendrait plus.

Thus I went to the home of Maréchale Davout, who had showered me with courtesies during her stay in Warsaw, when her husband was in command in Poland. As she spent the summers in Savigny (1), it is there that I had to go and find her. I wrote to her Paris house to find out the most convenient time to visit her, and was told that it would be in the daytime. So I went to Savigny on a broiling hot day, little protected from the sun by a very small hat adorned with violets, and very uncomfortable in my lilac booties perfectly matched with a high dress in taffeta in the same color; - Madame Germont, the oracle of fashion, had herself arranged my costume.

[...]

I had promised myself this would be a pleasant visit. The Maréchale's Paris residence had much impressed me with her taste and love of fashion, and I thought I would find her luxuriously settled in Savigny. I arrived at about three o'clock. The door of the chateau, which was encircled by a moat and an enclosure, was hermetically sealed. Tall grasses were growing in the moat; the chateau had the appearance of having been deserted for many years. My footman having finally found the doorbell, a little girl, rather ill-dressed, appeared, after a few minutes, to ask what was wanted.

- "Is Madame la Maréchale at home?"

- "Oh, but yes, they are there, and so is the Marshal," answered the little girl.

And she hurried to summon one of the servants of the chateau, who proceeded to follow her at a leisurely pace, adjusting his livery as he went.

I had myself announced, and huddling in the carriage, I waited for quite a while, wondering whether I should insist or whether I ought to simply leave a visiting card.

After a mere quarter of an hour, a manservant finally appeared at the door of my carriage and led me into a vast courtyard; he apologized for the slowness of the service, informing me without particular deference that at the moment I arrived, the household staff was working in the garden, and that he himself had been engaged in tidying the orchard.

I was led through several completely unfurnished salons; the room into which I was ushered was hardly more ornate than the previous ones, but at least it had a sofa and chairs! The Maréchale presently appeared. I could easily perceive that she had just dressed up for me, because she was still busy fastening some pins to her bodice. After a few minutes of languishing conversation, she pulled the bellcord so her husband could be apprised of my presence. She and I then resumed our awkward conversation. It is not that Madame Davout's manners were lacking, or that she was deprived of that sort of wit which facilitates exchages between people of similar backgrounds, but there was in her manner a kind of stiffness which might be mistaken for arrogance. She never forgot about the marshalate; never did a gracious smile enliven the features of her austerely beautiful face. [...]

The Marshal finally arrived, his haste reflected in his heavy perspiration; out of breath, he sat down and, using his pocket handkerchief to wipe his forehead, he moistened it with saliva in order to more efficiently remove the dust from his face. This casualness, a bit too soldierly, contrasted sharply with the starchy demeanor of his wife; she was noticeably annoyed about it. Finding myself de trop in this silent scene, I rose and tried to take my leave, but I was enjoined to stay for a mid-day meal. While waiting for this to be served, we went a walk in the grounds... There were no paths, the lawn was covered with high grass ready to be turned into haystacks, the trees, cut down during the Revolution, were growing back as scrub; I left shreds of my dress's ruffles on each bush, and my lilac booties had taken on a greenish tinge. The Marshal encouraged us by voice and by gesture with the promise of a charming surprise!... What disappointment when, at the bend of a clump of stripling oaks, we finally stood in front of three small wicker huts! The Duke went down on one knee and exclaimed:

- "Ah! here they are... here they are!..."

Then, modulating his voice:

- "Pi... pi... pi..."

And at once a swarm of partridges began to flutter around the Marshal’s head.

- "Don't let the others go out until the youngest have returned, and give the ladies some bread... They are going to enjoy themselves like queens", he said to a roughneck who was the gamekeeper.

And there we were, under scorching sunshine, feeding partridges!

With unruffled and imperturbable dignity, the Duchess emptied the basket of bread she had been given. I, on the other hand, came close to fainting, and this being beyond my endurance, I pointed out that clouds were moving in and that a storm threatened.

[...]

Once we had finished eating, I left in greatest haste, swearing to myself that this visit would not be repeated.

(1) Savigny-sur-Orge [this note appears in the original text]

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5463019n/f278.item pp. 229-234.

So there went the Countess’s pleasant visit, just not quite as pleasant as foreseen. I confess that I share her feelings about the spit-moistened handkerchief. And I too have been in the excruciating position of trying to make conversation when there is nothing to converse about. But she did not expect to have her fancy dress shredded by unkempt scrub. All this while traipsing in uncomfortable booties ruined by grass stains, the reward for this being to witness Davout calling his partridges in a falsetto voice, and a final indignity, bringing her close to fainting (or was it the foot-pinching booties?): having to feed breadcrumbs to partridges, while being expected to have fun doing it. Pass the smelling salts.

The food must have been good, because she does not have a word of criticism about it. No word whatsoever about it, in fact. I suppose no artichokes were served.

My little finger tells me the Davouts were not sorry to see the back of her, unless her manners were so exquisite that she was able to feign delight through her visit. But then again there was this laboured conversation, so... no. They were glad she left.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

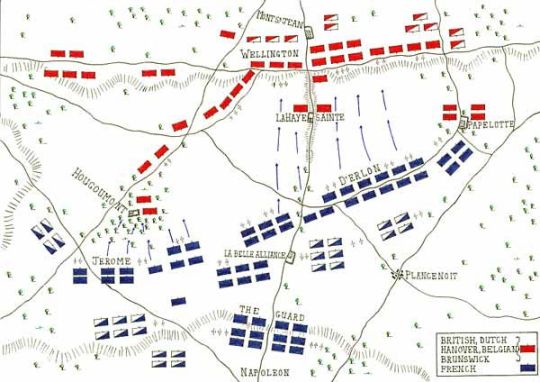

Anonymous asked: I loved your fantastic account of the battle of Waterloo and how each nation came to define the rest of the century for all the European countries in different ways. However what are your thoughts about the battle itself? Did Wellington win it or did Napoleon lose it? What were the turning points that you think determined the fate of the battle?

Thank you for reading and liking my previous post on Waterloo. I did heavily lean into studying ancient classical warfare when I was studying Classics but I only got into Napoleonic warfare because of a father who was (and still remains) big Napoleonic warfare military enthusiast. Through his keen eyes as a former serving military man, I also looked at the battle as a soldier might as well putting on my academic critical thinking cap. It’s a popular parlour game not just in Sandhurst but also in the officers’ mess (where those regiments actually fought at Waterloo) and around dinner tables - in my experience anyway.

I’ve always seen such speculative and counterfactual questions as an amusing diversion. I’ve never seriously looked at the detail until I came to France and unexpectedly interacted with Napoleonic scholars as well as soldiers (the cultured and historically well read ones at least) that forced me to think more about it. I’ve always been of the ‘if the Prussians hadn’t arrived in time to save Wellington’ school; and this was always enough to get me by in any conversation.

But my vanity was stung by interacting with one of my downstairs neighbours, a high decorated retired army general, with whom I played a weekly game of chess over a glass of wine during the Covid lockdown in Paris. He didn’t spare me as he knew so much detail about the battle. But a typical failing of French thinking is to pontificate around generalities rather than specific reasons. So for him it came down to pooh-poohing the generalship of Wellington (the rain saved him) and lauding the emperor (he had haemorrhoids and thus a bad day at the office). So rain and haemorrhoids were the decisive factors in determining the outcome of the battle of Waterloo.

It was clear I had to raise my game. So I’ve been reading more when I could.

I had recently finished reading a wonderful book ‘The Longest Afternoon: The 400 Men Who Decided the Battle of Waterloo’ by the Cambridge historian Brendan Simms. The book came out in 2015 but it’s been lying on my shelf for these past few years until I actually took this slim book to read on my one of my business trips.

The idea behind this short book is so superbly useful. It places to one side the huge, cinematic panorama of history and instead concentrates on one particular farmhouse, on one particular day: 18 June 1815. History is vivified, lifts itself off the page and into the mind, when a historian of Brendan Simm’s immense stature zooms in on the details - and here the details are compelling.

For the course of one day, 400 soldiers, wet, cold, in some cases hungover, who had bivouacked for the night in an abandoned farmhouse at La Haye Sainte, near a crucially strategic crossroads, found themselves staring down the massed barrels of Napoleon’s vanguard – and held them off. On June 18, 1815, Wellington established his position and sent one battalion and part of a second to the farmhouse under the command of Major Baring. Napoléon’s initial attack was a direct assault that surrounded the house and came near to breaking Wellington’s line; but it held, and the legendary charge of two British heavy cavalry brigades drove back the French.

This is a detailed account of the defence of La Haye Sainte, a walled stone farmhouse forward of Wellington’s centre. Its defenders were the King’s German Legion, which (despite the British army’s penchant for oddball names) was genuinely German. Britain harboured many German expatriates who detested Napoléon, a number augmented in 1803 when he occupied Hanover and disbanded its army. That very year two ambitious officers recruited the first members of the King’s German Legion, which grew into a corps of some 14,000 men and served with distinction at Copenhagen, Walcheren and in Spain before its apotheosis at Waterloo.

Ordered to capture the farmhouse, Marshal Michel Ney - commanding Napoléon’s left wing - obeyed but became preoccupied with his famously unsuccessful cavalry attack. Reminded of the order two hours later, he dispatched infantry that reached the house and set it on fire. The men inside controlled the blaze and continued to fight until Ney took personal charge of a furious assault that succeeded only when the defenders ran out of ammunition and withdrew, having held out for six hours. Had they not defended it so stoutly and if the farm had fallen any sooner then Napoleon would have been able to get at Wellington’s troops before his Prussian reinforcements arrived, and in all likelihood Waterloo would have been a French victory instead; it would now be the name of a train station in Paris rather than London.

I doubt there is a definitive answer to this question which is why certain people love arguing about it because it’s so open ended in terms of cause and effect. You can pick on any episodic event and hail that as the decisive turning point. It’s one reason why we are so fortunate to have so many well researched history books on the battle of Waterloo to replenish the issues for a newer generation to argue with past generations.

If I were to go beyond the ‘if the Prussians hadn’t arrived to save Wellington’ line then I would point to ten decisive turning points which in themselves might not have changed the outcome but taken together certainly influenced the final outcome of one of the most important and iconic battles in history.

Napoleon gives Marshal Davout a desk job

6 June 1815 – All commanders need a good chief of staff to ensure that their intentions are translated into clear orders. Unfortunately for Napoleon – as what is arguably one of the most decisive battles in European history loomed – his trusted chief of staff, Marshal Berthier, was no longer available. Berthier had sworn an oath of loyalty to Louis XVIII – and then fallen to his death from a window – so the job was given to Marshal Soult.

Soult was an experienced field commander but he was certainly no Berthier. Napoleon’s two main field commanders were also far from ideal. Emmanuel Grouchy had little experience of independent command. Michel Ney’s heroic command of the French rear-guard during the retreat from Moscow led Napoleon to dub him “the bravest of the brave”, but by 1815 he was clearly burnt out.

Worse still, when on 6 June Napoleon ordered his generals to assemble with their troops on the Belgian border he chose to leave behind Louis-Nicolas Davout, his ‘Iron Marshal’, as minister of war. The emperor needed someone loyal to oversee affairs at home but the decision not to take with him the ablest general at his disposal would deprive him of the one commander who might have made a difference.

Constant Rebecque ignores orders

15 June – In June 1815 Napoleon assembled 120,000 men on the Belgian border. Opposing him were 115,000 Prussians under Field Marshal Blücher and an allied force of about 93,000 men under Wellington. Faced with such odds, Napoleon’s best chance of victory was to get his army between his two enemies and defeat one before turning on the other. On 15 June his army crossed the frontier at Charleroi and headed straight for the gap between the two allied armies.

Wellington was taken completely by surprise: “Napoleon has humbugged me” he said. Uncertain what Napoleon’s intentions were, he ordered his army to concentrate around Nivelles, over 12 miles away from the Prussian position at Ligny. This would have left the two allied armies dangerously separated but fortunately for Wellington, a staff officer in the Dutch army, Baron Constant Rebecque, understood what was actually needed. He disregarded Wellington’s order and instead sent a force to occupy the key crossroads of Quatre Bras, much nearer to the Prussians.

D’Erlon misses the show

16 June – Two battles were fought on 16 June. While Marshal Ney took on Wellington’s army as it hurriedly tried to concentrate around Quatre Bras, Napoleon led the main French force against the Prussians at Ligny. Blücher’s inexperienced Prussians were given a severe mauling but despite this they managed to fall back in relatively good order.

This was partly due to a disastrous mix-up on the part of the French. Confusion over orders saw General D’Erlon’s corps instructed to leave Ney’s army at Quatre Bras and join the fighting at Ligny only to be recalled as soon as they got there. The result was that 16,000 Frenchmen who could have intervened decisively actually took part in neither battle.

Blücher stays in touch

17 June – Wellington succeeded in beating back Ney at Quatre Bras but Blücher’s defeat left the British general with a large French army on his eastern flank. He was forced to fall back northwards towards Brussels. The Prussians were retreating as well. Normally a retreating army tries to withdraw along its lines of communication (ie the route back to its base). Had the Prussians done this they would have headed eastwards. The two allied armies would then have been even further apart and Wellington would have been overwhelmed. But instead of doing that, the Prussians retreated northwards towards Wavre. It was to be a crucial move. The two allied armies stayed in contact and on 17 June Wellington was able to fall back to the ridge at Mont St Jean, and prepare to make a stand there until Blücher’s Prussians could come to his aid.

The weather takes a hand

17 June – The night before the battle was marked by a thunderstorm of biblical proportions. Rain lashed down, turning roads into quagmires and trampled fields into seas of mud.

It was a night of tremendous rain and cloudbursts. Wellington said that even in the monsoons in India, he’d never known rain like it. To wake up cold and damp, wet and terrified, then you have this slaughter in a very small space. By evening there were over 200,000 men struggling to kill each other within four square miles.

Private Wheeler of the 51st Regiment later wrote: “The ground was too wet to lie down… the water ran in streams from the cuffs of our Jackets… We had one consolation, we knew that the enemy were in the same plight.” Wheeler was right of course – the rain would inconvenience all three armies, not least the Prussians as they struggled along narrow country lanes to link up with Wellington.

It’s often said that Napoleon delayed starting the battle in order to allow the ground to dry out but the chief cause of the delay was probably the need to allow his units, many of whom had bivouacked some distance away, to take up their allotted places. Napoleon enjoyed a considerable advantage in artillery at Waterloo but this was lessened by the fact that the mud made it difficult to move his guns around and that cannonballs, normally designed to bounce along until they hit something, or someone, often disappeared harmlessly into the soggy ground.

Macdonnell closes the gates

11:30am, 18 June – On 18 June the two armies prepared to do battle. Most of Wellington’s troops were sheltered from enemy fire on the reverse slope of the Mont St Jean ridge. The position was protected by three important outposts: a group of farms to the left, the farm of La Haye Sainte in front and the farmhouse of Hougoumont to the right.

At about 11.30am the French launched their first attack – an assault on Hougoumont. This soon developed into a battle within a battle as the French threw in ever more men in a bid to capture the vital chateau. They nearly succeeded: led by a giant officer nicknamed ‘the Smasher’, a group of French soldiers worked their way round to the rear of the chateau, forced open its north gate and burst inside.

James Macdonnell, the garrison commander, acted quickly. He gathered a group of men and they heaved the gate shut again. The French inside the chateau were then hunted down and killed. Only a young drummer boy was spared. Hougoumont was to remain in allied hands all day and Wellington later commented that the entire result of the battle depended on the closing of those gates.

Ney loses his head after his cavalry founders

1.30pm – The infantry of D’Erlon’s corps finally saw action as they attacked the left wing of Wellington’s army. As they reached the crest of the ridge they were met by the infantry of Sir Thomas Picton’s division. Picton, a foul-mouthed Welshman who rode into battle in a civilian coat and round-brimmed hat, was shot dead but his men stopped the French, who were then driven back by Wellington’s cavalry.

The next major French attack was very different. Ney unleashed his cavalry in a mass frontal attack, and thousands of Napoleon’s famous cuirassiers – big men in steel breastplates riding big horses – thundered up the hill. But Wellington’s infantry stayed calm. Forming squares, they presented in all directions a hedge of bayonets that no horse could be made to charge.

Ney needed to call the cavalry off or support them with infantry but he lost his head and threw more horsemen into the fray. When he abandoned these fruitless attacks, Wellington’s line was still unbroken, two hours had been wasted, and the Prussians were arriving in force.

The Prussians arrive

4.30pm – Blücher had promised to come to Wellington’s aid, and kept his word. Napoleon had detached nearly a third of his army under Grouchy to prevent the Prussians joining up with Wellington but Grouchy failed to do this and, by mid-afternoon, the first Prussian units were in action on the battlefield.

At about 4.30pm they launched their first attack upon the key village of Plancenoit near the rear of Napoleon’s main position. This savage battle would rage for over three hours. Faced with this, Napoleon was forced to send many of his remaining reserves to shore up his position – leaving him with precious few troops to exploit any success his troops might enjoy against Wellington.

Napoleon says no, and von Zeithen turns back

6.30pm – At about 6.30pm the French captured La Haye Sainte. Posting artillery and skirmishers around the farm, they unleashed a storm of shot, shell and musketry into Wellington’s exposed centre. The regiments there suffered horrendous casualties, but Wellington’s line held – just.

Ney asked for reinforcements to press home his advantage but Napoleon refused. Instead he sent troops to recapture Plancenoit which had just fallen to the Prussians. Von Zeiten’s Prussian I Corps arrived on the scene. These much-needed reinforcements were set to join Wellington when a Prussian aide de camp rode up with an order from Blücher instructing them to head south and support his troops at Plancenoit. Von Zeiten obeyed. Realising that Von Zeiten’s troops were desperately needed on the ridge, Baron von Müffling, Wellington’s Prussian liaison officer, galloped after Von Zeiten and pleaded with him to ignore this new order and stick to the original plan. The Prussian general turned back and took his place on Wellington’s left, enabling the duke to shift troops over to reinforce his crumbling centre. The crisis had passed.

Napoleon’s last roll of the dice ends in panic

7.30pm – With Plancenoit back in French hands the stage was set for the final act in the drama. At about 7.30pm Napoleon unleashed his elite imperial guard in a last desperate bid for victory. But it was too late – they were hopelessly outnumbered and Wellington was ready for them. His own troops had been sheltering from the French fire by lying down but when the two large columns of French guardsmen reached the crest of the ridge Wellington ordered his own guards to stand up. One British guardsman describes the scene: “Whether it was (our) sudden appearance so near to them, or the tremendously heavy fire we threw into them but La Garde, who had never previously failed in an attack, suddenly stopped.”

Meanwhile Sir John Colborne of the 52nd Light Infantry wheeled his regiment round to attack the flank of the first French column while General Chasse ordered his Dutch and Belgian troops forward against the other. Soon both French columns had withered away under the deadly fire. Their defeat led to widespread panic in the French army: amid cries of “La Garde recule” (“the Guard is retreating”) it dissolved into a disorderly retreat mercilessly harried by the Prussians. “The nearest-run thing you ever saw in your life,” as Wellington described the battle, was over.

This isn’t an exhaustive list but it will do.

Waterloo was a watershed moment for Europe, and indeed the world. The end of the Napoleonic Wars heralded a peace in Europe which was not broken until the outbreak of World War One in 1914. In the century following the Battle of Waterloo an increased respect developed for the figure of the soldier. True the Battle became mythologised in the nineteenth century and is now embedded in our cultural memory as one of the great British success stories.

We still celebrate Waterloo because it was a great British victory - even if we had a little bit of help from the Prussians. It embodied the British bulldog spirit and marked the moment we finally overcame Napoleon and his empire after a decade of being at war.

The ramifications from Waterloo and the Napoleonic Wars are still felt today in contemporary European politics. I think because of this the battle continues to fascinate and to court intense discussion and disagreement.

No doubt my French neighbour the retired army general and I will continue to stubbornly argue our differing viewpoints until the wine bottle empties. But we both agree that we would enjoy having dinner with Napoleon and talk about his military campaigns. I admire Napoleon a little more having read more and for living in France. He’d be a very amusing and stimulating companion.

In many ways, he was also an enlightened and intelligent ruler. His Code Napoleon is an extremely enlightened law code. At the same time this is a man who had a very, very low threshold for boredom. I think he was addicted to war.

General Robert E. Lee, at Fredericksburg said, “It is well that war is so dreadful, otherwise we would grow too fond of it.”

Napoleon would never have agreed with that. War was his drug. There’s no evidence that Wellington enjoyed war. He said after Waterloo, and I believe him, “I pray to God that I have fought my last battle.” He spent much of the battle saying to the men, “If you survive, if you just stand there and repel the French, I’ll guarantee you a generation of peace.” He thought the point of war was peace. And he sure gave not just Britain but also an entire European continent some respite from the spilling of blood on a battlefield.

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#waterloo#battle#battle of waterloo#napoleon#wellington#history#britain#france#prussia#austria#german#europe#military#british army#soldier

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 4.19

AD 65 – The freedman Milichus betrays Piso's plot to kill the Emperor Nero and all the conspirators are arrested.

531 – Battle of Callinicum: A Byzantine army under Belisarius is defeated by the Persians at Raqqa (northern Syria).

797 – Empress Irene organizes a conspiracy against her son, the Byzantine emperor Constantine VI. He is deposed and blinded. Shortly after, Constantine dies of his wounds; Irene proclaims herself basileus.

1506 – The Lisbon Massacre begins, in which accused Jews are being slaughtered by Portuguese Catholics.

1529 – Beginning of the Protestant Reformation: After the Second Diet of Speyer bans Lutheranism, a group of rulers (German: Fürst) and independent cities protests the reinstatement of the Edict of Worms.

1539 – The Treaty of Frankfurt between Protestants and the Holy Roman Emperor is signed.

1608 – In Ireland: O'Doherty's Rebellion is launched by the Burning of Derry.

1677 – The French army captures the town of Cambrai held by Spanish troops.

1713 – With no living male heirs, Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, issues the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 to ensure that Habsburg lands and the Austrian throne would be inheritable by a female; his daughter and successor, Maria Theresa was not born until 1717.

1770 – Captain James Cook, still holding the rank of lieutenant, sights the eastern coast of what is now Australia.

1770 – Marie Antoinette marries Louis XVI of France in a proxy wedding.

1775 – American Revolutionary War: The war begins with an American victory in Concord during the battles of Lexington and Concord.

1782 – John Adams secures Dutch recognition of the United States as an independent government. The house which he had purchased in The Hague becomes the first American embassy.

1809 – An Austrian corps is defeated by the forces of the Duchy of Warsaw in the Battle of Raszyn, part of the struggles of the Fifth Coalition. On the same day the Austrian main army is defeated by a First French Empire Corps led by Louis-Nicolas Davout at the Battle of Teugen-Hausen in Bavaria, part of a four-day campaign that ended in a French victory.

1810 – Venezuela achieves home rule: Vicente Emparán, Governor of the Captaincy General is removed by the people of Caracas and a junta is installed.

1818 – French physicist Augustin Fresnel signs his preliminary "Note on the Theory of Diffraction" (deposited on the following day). The document ends with what we now call the Fresnel integrals.

1839 – The Treaty of London establishes Belgium as a kingdom and guarantees its neutrality.

1861 – American Civil War: Baltimore riot of 1861: A pro-Secession mob in Baltimore attacks United States Army troops marching through the city.

1903 – The Kishinev pogrom in Kishinev (Bessarabia) begins, forcing tens of thousands of Jews to later seek refuge in Palestine and the Western world.

1927 – Mae West is sentenced to ten days in jail for obscenity for her play Sex.

1942 – World War II: In German-occupied Poland, the Majdan-Tatarski ghetto is established, situated between the Lublin Ghetto and a Majdanek subcamp.

1943 – World War II: In German-occupied Poland, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising begins, after German troops enter the Warsaw Ghetto to round up the remaining Jews.

1943 – Albert Hofmann deliberately doses himself with LSD for the first time, three days after having discovered its effects on April 16.

1956 – Actress Grace Kelly marries Prince Rainier of Monaco.

1960 – Students in South Korea hold a nationwide pro-democracy protest against president Syngman Rhee, eventually forcing him to resign.

1971 – Sierra Leone becomes a republic, and Siaka Stevens the president.

1971 – Launch of Salyut 1, the first space station.

1971 – Charles Manson is sentenced to death (later commuted to life imprisonment) for conspiracy in the Tate–LaBianca murders.

1973 – The Portuguese Socialist Party is founded in the German town of Bad Münstereifel.

1975 – India's first satellite Aryabhata launched in orbit from Kapustin Yar, Russia.

1975 – South Vietnamese forces withdrew from the town of Xuan Loc in the last major battle of the Vietnam War.

1984 – Advance Australia Fair is proclaimed as Australia's national anthem, and green and gold as the national colours.

1985 – Two hundred ATF and FBI agents lay siege to the compound of the white supremacist survivalist group The Covenant, The Sword, and the Arm of the Lord in Arkansas; the CSA surrenders two days later.

1987 – The Simpsons first appear as a series of shorts on The Tracey Ullman Show, first starting with "Good Night".

1989 – A gun turret explodes on the USS Iowa, killing 47 sailors.

1993 – The 51-day FBI siege of the Branch Davidian building in Waco, Texas, USA, ends when a fire breaks out. 76 Davidians, including eighteen children under the age of ten, died in the fire.

1995 – Oklahoma City bombing: The Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, USA, is bombed, killing 168 people including 19 children under the age of six.

1999 – The German Bundestag returns to Berlin.

2000 – Air Philippines Flight 541 crashes in Samal, Davao del Norte, killing all 131 people on board.

2005 – Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger is elected to the papacy and becomes Pope Benedict XVI.

2011 – Fidel Castro resigns as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba after holding the title since July 1961.

2013 – Boston Marathon bombing suspect Tamerlan Tsarnaev is killed in a shootout with police. His brother Dzhokhar is later captured hiding in a boat inside a backyard in the suburb of Watertown.

2020 – A killing spree in Nova Scotia, Canada, leaves 22 people and the perpetrator dead, making it the deadliest rampage in the country's history.

2021 – Ingenuity helicopter achieves the first flight on another planet in history.

0 notes

Text

Louise Soult’s health

A lot has been said already about Aimée Davout’s health issues and her “melancholy” (which we would today probably call a depression). But the long separations from their husbands, the stress to manage court duties and financial issues, to raise their children alone, and last but not least the daily concern for a husband at war, all that took its toll on probably most of the marshals’ wives. Louise Berg-Soult to me comes across as a very calm, thoughtful, stable personality. But she, too, suffered from a long period of “maux de nerfs”, a nervous breakdown with insomnia, restlessness, anxiety and depressive phases, during spring and summer 1807, when Soult fought in Poland.

On 29 March 1807, the day of his birthday, Soult writes to her:

I'm very sorry to see you still suffering from nervous problems. Your imagination worries you too much, my good friend, and you should moderate yourself. Think, I beg you, of the three objects who, for their happiness, impose on you the sacred duty of taking care of your health; and may the hope of seeing all three of them looking after your own happiness dispel the sorrows and pains that my absence and my situation can cause you.

However, the situation worsens over the next weeks, to the point when the doctor feels he has to write to Soult directly (as Louise herself was quite “laconic” about it, in Soult’s words). Soult of course freaks out, insists that the doctor write to him every day and Louise as often as she manages, sends her to their country estate, implores her to take care of herself etc. But it still takes until July for her to recover, when after the peace of Tilsit there is a chance that Soult might either come home or she might go see him (it would be the latter option).

As Nicole Gotteri notes in her book on Soult, Louise often copied sentences from books she had read and that resonated with her in a notebook. One of them read:

Strong souls keep their secret of joy or sadness and don't let it show on their foreheads.

So she somehow managed to fight through her own periods of anxiety and depression by putting on a mask, and by sheer self discipline. It would explain why she was often looking after Aimée Davout. She could relate to what Aimée was going through.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

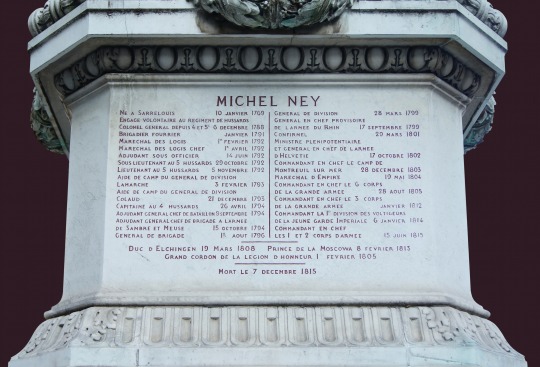

“The Bravest of the Brave”: Marshal Ney, the soldier’s soldier.

Michel Ney, duke d’Elchingen, (10 Jan 1769 - 7 Dec 1815), one of the best known of Napoleon’s marshals (from 1804), who pledged his allegiance to the restored Bourbon monarchy when Napoleon abdicated in 1814. Upon Napoleon’s return in 1815, Ney rejoined him and commanded the Old Guard at the Battle of Waterloo. Under the monarchy, again restored, he was charged with treason, for which he was condemned and shot by a firing squad.

His execution like his soldiering life was the stuff of legends.

Beginnings

Ney was the son of a barrel cooper and blacksmith. Apprenticed to a local lawyer, he ran away in 1788 to join a hussar regiment. His opportunity came with the revolutionary wars, in which he fought from the early engagements at Valmy and Jemappes in 1792 to the final battle of the First Republic at Hohenlinden in 1800.

Ney’s legendary bravery was especially seen at Mannheim when a cannonball killed his horse and wounded his leg, and then when Ney stood up he was hit by a bullet to the chest which threw him to the ground. Luckily for him, the bullet was spent and did not pierce him, instead only giving him a bad bruise.

The early campaigns revealed two contrasting features of Ney’s character: his great courage under fire and his strong aversion to promotion. Willing to hurl himself into battle at critical moments to inspire his troops by his personal example, he was unwilling to accept higher rank, and when his name was put forward he protested to his military and political superiors. In every instance he was overruled: it was as general of a division that he fought in Victor Moreau’s Army of the Rhine at Hohenlinden.

He soon caught Napoleon’s eye and made rapid progress up the ranks. He didn’t disappoint. The further up the ranks he went the further into danger threw himself into. The men loved him and followed him anywhere.

On May 19, 1804, the day after Napoleon had had himself proclaimed hereditary emperor of the French, he revived the ancient military rank of marshal, and 14 generals, including Ney, were gazetted marshals of the empire.

The Russian campaign of 1812 cemented his legend. On the morning after the somewhat inconclusive battle at Borodino, Napoleon made him prince de la Moskowa. On the retreat from Moscow, Ney was in command of the rear guard, a position in which he was exposed to Russian artillery fire and to numerous Cossack attacks. He rose to heights of courage, resourcefulness, and inspired improvisation that seemed miraculous to the men he led. “He is the bravest of the brave,” said Napoleon when Ney, for weeks given up as lost, joined the main body of the frozen and shrunken Grand Army.

The fall of Napoleon and the rise of the Bourbons

But after 1813 and the with the Winter disaster in Russia, Napoleon suffered a series of setbacks that eventually pushed him back to France and to the brink of defeat.

Napoleon concentrated his remaining forces at Fontainebleau to fight the allies in Paris, but Ney, speaking for himself and other marshals, told him that the army would not march. “The army will obey me,” said Napoleon. “Sire,” replied the Bravest of the Brave, “the army will obey its generals.” Napoleon was forced to abdicate. Ney retained his rank and titles and took an oath of fidelity to the Bourbon dynasty.

With the Bourbons returned to power in France in 1814, Marshal Ney rallied to them in the hopes of a peaceful and stable France. In response, he was made a Knight of Saint-Louis and Peer of France and he was placed in charge of the cavalry. However, despite these rewards he could only watch as the government grew inefficient and old privileges granted to the nobility were restored, going against the very changes that had allowed him to rise so high.

Furthermore, since he was the first Duke of Elchingen and first Prince of the Moskowa, he and his wife were frequently snubbed by the returned nobility with famous ancestors.

One day he returned home to find his wife in tears over more ill treatment received from the Duchess of Angoulême. Enraged, Ney charged to the Tuileries where he burst in, politely and quickly paid his respects to the king, and then verbally berated the Duchess, beginning with, "I and others were fighting for France while you sat sipping tea in English gardens," and ending with, "You don't seem to know what the name Ney means, but one of these days I'll show you!"

The 100 Days and the Battle of Waterloo

When in 1815 Napoleon escaped from Elba and began his triumphant march back to Paris, Ney was horrified by the prospect of civil war. Despite his dislike of the Bourbons, he told the king he would bring Napoleon back to Paris in an iron cage. As Ney led his troops in a march to intercept Napoleon, his doubts began to grow. The people of France and the army all seemed to be cheering for Napoleon, and no one had fired a shot to stop Napoleon. During every step of Napoleon's progress, more and more had joined his side.

If Ney ordered his men to fight Napoleon and his men, Ney might be the cause of civil war, presuming that his men would even follow his orders and shoot at their former emperor. After receiving a message from Napoleon, Ney decided that he could not fight the tide and told his men that the legitimate dynasty of France as chosen by the people was Napoleon. His men began cheering, and he sent off messages stating his intent to rejoin Napoleon.

Despite Ney’s conduct, Napoleon wanted his ‘bravest of the brave’ by his side once again. Ney decided to take up the offer and assumed command of the left wing of the Army of the North. Almost immediately he was thrust into action, fighting the British at Quatre-Bras on June 16th. Two days later he fought at the Battle of Waterloo, leading from the front and having four horses killed underneath him over the course of the battle. When the French began to break and be overrun by the combined Prussian and British forces, Ney said, "Come and see how a Marshal of France dies!"4

Ney escaped from Waterloo and returned to Paris where the Minister of Police Fouché gave him passports which he did not use. After Napoleon's second abdication, Marshal Davout took command of the army and refused to surrender until a treaty was signed that granted amnesty to those who had rejoined Napoleon. Ney went into hiding at a friend's chateau, but he was soon spotted and arrested. Even the king was upset that he had not fled the country, hoping to avoid a trial that could expose the internal divisions of the people. After giving his promise to not flee, Ney was escorted back to Paris without being bound. On the way General Exelmans came to his rescue, but Ney refused to go against his word to his captors, and he continued back to Paris.

Trial and execution

Initially Ney was to be tried by a military court run by Marshal Jourdan, however his defense team argued that this court could not try him, and instead his case should be tried in the Chamber of Peers. His defense team won in this regard when the court declared itself incompetent, though that may have been due to the military court not wanting to convict him but also not wanting to defy the Bourbons by acquitting him. Next Ney would be tried by a group populated by Royalists and without the same sense of honor as his military colleagues.

During the trial in the Chamber of Peers, Ney's lawyers brought up how the trial was in direct violation of the treaty Davout had negotiated, and secretly in response a new law was then passed forbidding mentioning that treaty in court. With such an act, it became clear to everyone that the trial was a witch hunt. As a last attempt, his lawyers argued that since Ney's hometown of Saarelouis was ceded to Prussia, he could not be tried as a Frenchman, but Ney vehemently denounced this tactic and demanded to be tried as a Frenchman. Some of Ney's supporters appealed to the British for assistance, but they refused, claiming that they could not meddle in France's internal affairs despite spending the past twenty five years trying to change France's government.

On December 6th, Ney was convicted by the Chamber of Peers and the Peers also voted on his sentence, with the majority voting for death by firing squad. The execution was to be carried out the next day. When news of Ney's sentence reached the public, a mob began to form where the execution was to take place, and a new place of execution was quickly arranged at a different location.

Ney faced his execution by firing squad in Paris near the Luxembourg Garden. He refused to wear a blindfold and was allowed the right to give the order to fire, reportedly saying:

“Soldiers, when I give the command to fire, fire straight at my heart. Wait for the order. It will be my last to you. I protest against my condemnation. I have fought a hundred battles for France, and not one against her ... Soldiers, fire!”

Marshal Michel Ney was a soldier’s soldier.

Ney was wholly without political ambition or judgment. He was at his greatest in the campaigns for France’s natural frontiers at the beginning and end of his career, but out of his depth in Napoleon’s intricate strategy for the domination of Europe. He showed little interest in external distinctions or social success. The dignity with which he met his death effaced the memory of his political vagaries and made him, in an epic age, the most heroic figure of his time.

21 notes

·

View notes