#der zeitgeist

Text

#art#Zeitgeist#painting#figure realism#alte nationalgalerie#Der Zug des Todes#gustave adolph spangenberg

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

radio: präsident barack obama...

bob: barack obama?? hm. schon wieder keine frau...

#bob said feminism#die drei fragezeichen#die drei fragezeichen und der zeitgeist#die drei ???#bob andrews#mine

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

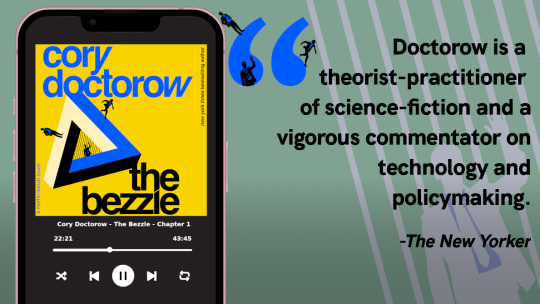

My McLuhan lecture on enshittification

IT'S THE LAST DAY for the Kickstarter for the audiobook of The Bezzle, the sequel to Red Team Blues, narrated by @wilwheaton! You can pre-order the audiobook and ebook, DRM free, as well as the hardcover, signed or unsigned. There's also bundles with Red Team Blues in ebook, audio or paperback.

youtube

Last night, I gave the annual Marshall McLuhan lecture at the Transmediale festival in Berlin. The event was sold out and while there's a video that'll be posted soon, they couldn't get a streaming setup installed in the Canadian embassy, where the talk was held:

https://transmediale.de/en/2024/event/mcluhan-2024

The talk went of fabulously, and was followed by commentary from Frederike Kaltheuner (Human Rights Watch) and a discussion moderated by Helen Starr. While you'll have to wait a bit for the video, I thought that I'd post my talk notes from last night for the impatient among you.

I want to thank the festival and the embassy staff for their hard work on an excellent event. And now, on to the talk!

Last year, I coined the term 'enshittification,' to describe the way that platforms decay. That obscene little word did big numbers, it really hit the zeitgeist. I mean, the American Dialect Society made it their Word of the Year for 2023 (which, I suppose, means that now I'm definitely getting a poop emoji on my tombstone).

So what's enshittification and why did it catch fire? It's my theory explaining how the internet was colonized by platforms, and why all those platforms are degrading so quickly and thoroughly, and why it matters – and what we can do about it.

We're all living through the enshittocene, a great enshittening, in which the services that matter to us, that we rely on, are turning into giant piles of shit.

It's frustrating. It's demoralizing. It's even terrifying.

I think that the enshittification framework goes a long way to explaining it, moving us out of the mysterious realm of the 'great forces of history,' and into the material world of specific decisions made by named people – decisions we can reverse and people whose addresses and pitchfork sizes we can learn.

Enshittification names the problem and proposes a solution. It's not just a way to say 'things are getting worse' (though of course, it's fine with me if you want to use it that way. It's an English word. We don't have der Rat für Englisch Rechtschreibung. English is a free for all. Go nuts, meine Kerle).

But in case you want to use enshittification in a more precise, technical way, let's examine how enshittification works.

It's a three stage process: First, platforms are good to their users; then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers; finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, they die.

Let's do a case study. What could be better than Facebook?

Facebook is a company that was founded to nonconsensually rate the fuckability of Harvard undergrads, and it only got worse after that.

When Facebook started off, it was only open to US college and high-school kids with .edu and k-12.us addresses. But in 2006, it opened up to the general public. It told them: “Yes, I know you’re all using Myspace. But Myspace is owned by Rupert Murdoch, an evil, crapulent senescent Australian billionaire, who spies on you with every hour that God sends.

“Sign up with Facebook and we will never spy on you. Come and tell us who matters to you in this world, and we will compose a personal feed consisting solely of what those people post for consumption by those who choose to follow them.”

That was stage one. Facebook had a surplus — its investors’ cash — and it allocated that surplus to its end-users. Those end-users proceeded to lock themselves into FB. FB — like most tech businesses — has network effects on its side. A product or service enjoys network effects when it improves as more people sign up to use it. You joined FB because your friends were there, and then others signed up because you were there.

But FB didn’t just have high network effects, it had high switching costs. Switching costs are everything you have to give up when you leave a product or service. In Facebook’s case, it was all the friends there that you followed and who followed you. In theory, you could have all just left for somewhere else; in practice, you were hamstrung by the collective action problem.

It’s hard to get lots of people to do the same thing at the same time. You and your six friends here are going to struggle to agree on where to get drinks after tonight's lecture. How were you and your 200 Facebook friends ever gonna agree on when it was time to leave Facebook, and where to go?

So FB’s end-users engaged in a mutual hostage-taking that kept them glued to the platform. Then FB exploited that hostage situation, withdrawing the surplus from end-users and allocating it to two groups of business customers: advertisers, and publishers.

To the advertisers, FB said, 'Remember when we told those rubes we wouldn’t spy on them? We lied. We spy on them from asshole to appetite. We will sell you access to that surveillance data in the form of fine-grained ad-targeting, and we will devote substantial engineering resources to thwarting ad-fraud. Your ads are dirt cheap to serve, and we’ll spare no expense to make sure that when you pay for an ad, a real human sees it.'

To the publishers, FB said, 'Remember when we told those rubes we would only show them the things they asked to see? We lied!Upload short excerpts from your website, append a link, and we will nonconsensually cram it into the eyeballs of users who never asked to see it. We are offering you a free traffic funnel that will drive millions of users to your website to monetize as you please, and those users will become stuck to you when they subscribe to your feed.' And so advertisers and publishers became stuck to the platform, too, dependent on those users.

The users held each other hostage, and those hostages took the publishers and advertisers hostage, too, so that everyone was locked in.

Which meant it was time for the third stage of enshittification: withdrawing surplus from everyone and handing it to Facebook’s shareholders.

For the users, that meant dialing down the share of content from accounts you followed to a homeopathic dose, and filling the resulting void with ads and pay-to-boost content from publishers.

For advertisers, that meant jacking up prices and drawing down anti-fraud enforcement, so advertisers paid much more for ads that were far less likely to be seen by a person.

For publishers, this meant algorithmically suppressing the reach of their posts unless they included an ever-larger share of their articles in the excerpt, until anything less than fulltext was likely to be be disqualified from being sent to your subscribers, let alone included in algorithmic suggestion feeds.

And then FB started to punish publishers for including a link back to their own sites, so they were corralled into posting fulltext feeds with no links, meaning they became commodity suppliers to Facebook, entirely dependent on the company both for reach and for monetization, via the increasingly crooked advertising service.

When any of these groups squawked, FB just repeated the lesson that every tech executive learned in the Darth Vader MBA: 'I have altered the deal. Pray I don’t alter it any further.'

Facebook now enters the most dangerous phase of enshittification. It wants to withdraw all available surplus, and leave just enough residual value in the service to keep end users stuck to each other, and business customers stuck to end users, without leaving anything extra on the table, so that every extractable penny is drawn out and returned to its shareholders.

But that’s a very brittle equilibrium, because the difference between “I hate this service but I can’t bring myself to quit it,” and “Jesus Christ, why did I wait so long to quit? Get me the hell out of here!” is razor thin

All it takes is one Cambridge Analytica scandal, one whistleblower, one livestreamed mass-shooting, and users bolt for the exits, and then FB discovers that network effects are a double-edged sword.

If users can’t leave because everyone else is staying, when when everyone starts to leave, there’s no reason not to go, too.

That’s terminal enshittification, the phase when a platform becomes a pile of shit. This phase is usually accompanied by panic, which tech bros euphemistically call 'pivoting.'

Which is how we get pivots like, 'In the future, all internet users will be transformed into legless, sexless, low-polygon, heavily surveilled cartoon characters in a virtual world called "metaverse," that we ripped off from a 25-year-old satirical cyberpunk novel.'

That's the procession of enshittification. If enshittification were a disease, we'd call that enshittification's "natural history." But that doesn't tell you how the enshittification works, nor why everything is enshittifying right now, and without those details, we can't know what to do about it.

What led to the enshittocene? What is it about this moment that led to the Great Enshittening? Was it the end of the Zero Interest Rate Policy? Was it a change in leadership at the tech giants? Is Mercury in retrograde?

None of the above.

The period of free fed money certainly led to tech companies having a lot of surplus to toss around. But Facebook started enshittifying long before ZIRP ended, so did Amazon, Microsoft and Google.

Some of the tech giants got new leaders. But Google's enshittification got worse when the founders came back to oversee the company's AI panic (excuse me, 'AI pivot').

And it can't be Mercury in retrograde, because I'm a cancer, and as everyone knows, cancers don't believe in astrology.

When a whole bunch of independent entities all change in the same way at once, that's a sign that the environment has changed, and that's what happened to tech.

Tech companies, like all companies, have conflicting imperatives. On the one hand, they want to make money. On the other hand, making money involves hiring and motivating competent staff, and making products that customers want to buy. The more value a company permits its employees and customers to carve off, the less value it can give to its shareholders.

The equilibrium in which companies produce things we like in honorable ways at a fair price is one in which charging more, worsening quality, and harming workers costs more than the company would make by playing dirty.

There are four forces that discipline companies, serving as constraints on their enshittificatory impulses.

First: competition. Companies that fear you will take your business elsewhere are cautious about worsening quality or raising prices.

Second: regulation. Companies that fear a regulator will fine them more than they expect to make from cheating, will cheat less.

These two forces affect all industries, but the next two are far more tech-specific.

Third: self-help. Computers are extremely flexible, and so are the digital products and services we make from them. The only computer we know how to make is the Turing-complete Von Neumann machine, a computer that can run every valid program.

That means that users can always avail themselves of programs that undo the anti-features that shift value from them to a company's shareholders. Think of a board-room table where someone says, 'I've calculated that making our ads 20% more invasive will net us 2% more revenue per user.'

In a digital world, someone else might well say 'Yes, but if we do that, 20% of our users will install ad-blockers, and our revenue from those users will drop to zero, forever.'

This means that digital companies are constrained by the fear that some enshittificatory maneuver will prompt their users to google, 'How do I disenshittify this?'

Fourth and finally: workers. Tech workers have very low union density, but that doesn't mean that tech workers don't have labor power. The historical "talent shortage" of the tech sector meant that workers enjoyed a lot of leverage over their bosses. Workers who disagreed with their bosses could quit and walk across the street and get another job – a better job.

They knew it, and their bosses knew it. Ironically, this made tech workers highly exploitable. Tech workers overwhelmingly saw themselves as founders in waiting, entrepreneurs who were temporarily drawing a salary, heroic figures of the tech mission.

That's why mottoes like Google's 'don't be evil' and Facebook's 'make the world more open and connected' mattered: they instilled a sense of mission in workers. It's what Fobazi Ettarh calls 'vocational awe, 'or Elon Musk calls being 'extremely hardcore.'

Tech workers had lots of bargaining power, but they didn't flex it when their bosses demanded that they sacrifice their health, their families, their sleep to meet arbitrary deadlines.

So long as their bosses transformed their workplaces into whimsical 'campuses,' with gyms, gourmet cafeterias, laundry service, massages and egg-freezing, workers could tell themselves that they were being pampered – rather than being made to work like government mules.

But for bosses, there's a downside to motivating your workers with appeals to a sense of mission, namely: your workers will feel a sense of mission. So when you ask them to enshittify the products they ruined their health to ship, workers will experience a sense of profound moral injury, respond with outrage, and threaten to quit.

Thus tech workers themselves were the final bulwark against enshittification,

The pre-enshittification era wasn't a time of better leadership. The executives weren't better. They were constrained. Their worst impulses were checked by competition, regulation, self-help and worker power.

So what happened?

One by one, each of these constraints was eroded until it dissolved, leaving the enshittificatory impulse unchecked, ushering in the enshittoscene.

It started with competition. From the Gilded Age until the Reagan years, the purpose of competition law was to promote competition. US antitrust law treated corporate power as dangerous and sought to blunt it. European antitrust laws were modeled on US ones, imported by the architects of the Marshall Plan.

But starting in the neoliberal era, competition authorities all over the world adopted a doctrine called 'consumer welfare,' which held that monopolies were evidence of quality. If everyone was shopping at the same store and buying the same product, that meant it was the best store, selling the best product – not that anyone was cheating.

And so all over the world, governments stopped enforcing their competition laws. They just ignored them as companies flouted them. Those companies merged with their major competitors, absorbed small companies before they could grow to be big threats. They held an orgy of consolidation that produced the most inbred industries imaginable, whole sectors grown so incestuous they developed Habsburg jaws, from eyeglasses to sea freight, glass bottles to payment processing, vitamin C to beer.

Most of our global economy is dominated by five or fewer global companies. If smaller companies refuse to sell themselves to these cartels, the giants have free rein to flout competition law further, with 'predatory pricing' that keeps an independent rival from gaining a foothold.

When Diapers.com refused Amazon's acquisition offer, Amazon lit $100m on fire, selling diapers way below cost for months, until diapers.com went bust, and Amazon bought them for pennies on the dollar, and shut them down.

Competition is a distant memory. As Tom Eastman says, the web has devolved into 'five giant websites filled with screenshots of text from the other four,' so these giant companies no longer fear losing our business.

Lily Tomlin used to do a character on the TV show Laugh In, an AT&T telephone operator who'd do commercials for the Bell system. Each one would end with her saying 'We don't care. We don't have to. We're the phone company.'

Today's giants are not constrained by competition.

They don't care. They don't have to. They're Google.

That's the first constraint gone, and as it slipped away, the second constraint – regulation – was also doomed.

When an industry consists of hundreds of small- and medium-sized enterprises, it is a mob, a rabble. Hundreds of companies can't agree on what to tell Parliament or Congress or the Commission. They can't even agree on how to cater a meeting where they'd discuss the matter.

But when a sector dwindles to a bare handful of dominant firms, it ceases to be a rabble and it becomes a cartel.

Five companies, or four, or three, or two, or just one company finds it easy to converge on a single message for their regulators, and without "wasteful competition" eroding their profits, they have plenty of cash to spread around.

Like Facebook, handing former UK deputy PM Nick Clegg millions every year to sleaze around Europe, telling his former colleagues that Facebook is the only thing standing between 'European Cyberspace' and the Chinese Communist Party.

Tech's regulatory capture allows it to flout the rules that constrain less concentrated sectors. They can pretend that violating labor, consumer and privacy laws is fine, because they violate them with an app.

This is why competition matters: it's not just because competition makes companies work harder and share value with customers and workers, it's because competition keeps companies from becoming too big to fail, and too big to jail.

Now, there's plenty of things we don't want improved through competition, like privacy invasions. After the EU passed its landmark privacy law, the GDPR, there was a mass-extinction event for small EU ad-tech companies. These companies disappeared en masse, and that's fine.

They were even more invasive and reckless than US-based Big Tech companies. After all, they had less to lose. We don't want competition in commercial surveillance. We don't want to produce increasing efficiency in violating our human rights.

But: Google and Facebook – who pretend they are called Alphabet and Meta – have been unscathed by European privacy law. That's not because they don't violate the GDPR (they do!). It's because they pretend they are headquartered in Ireland, one of the EU's most notorious corporate crime-havens.

And Ireland competes with the EU other crime havens – Malta, Luxembourg, Cyprus and sometimes the Netherlands – to see which country can offer the most hospitable environment for all sorts of crimes. Because the kind of company that can fly an Irish flag of convenience is mobile enough to change to a Maltese flag if the Irish start enforcing EU laws.

Which is how you get an Irish Data Protection Commission that processes fewer than 20 major cases per year, while Germany's data commissioner handles more than 500 major cases, even though Ireland is nominal home to the most privacy-invasive companies on the continent.

So Google and Facebook get to act as though they are immune to privacy law, because they violate the law with an app; just like Uber can violate labor law and claim it doesn't count because they do it with an app.

Uber's labor-pricing algorithm offers different drivers different payments for the same job, something Veena Dubal calls 'algorithmic wage discrimination.' If you're more selective about which jobs you'll take, Uber will pay you more for every ride.

But if you take those higher payouts and ditch whatever side-hustle let you cover your bills which being picky about your Uber drives, Uber will incrementally reduce the payment, toggling up and down as you grow more or less selective, playing you like a fish on a line until you eventually – inevitably – lose to the tireless pricing robot, and end up stuck with low wages and all your side-hustles gone.

Then there's Amazon, which violates consumer protection laws, but says it doesn't matter, because they do it with an app. Amazon makes $38b/year from its 'advertising' system. 'Advertising' in quotes because they're not selling ads, they're selling placements in search results.

The companies that spend the most on 'ads' go to the top, even if they're offering worse products at higher prices. If you click the first link in an Amazon search result, on average you will pay a 29% premium over the best price on the service. Click one of the first four items and you'll pay a 25% premium. On average you have to go seventeen items down to find the best deal on Amazon.

Any merchant that did this to you in a physical storefront would be fined into oblivion. But Amazon has captured its regulators, so it can violate your rights, and say, "it doesn't count, we did it with an app"

This is where that third constraint, self-help, would sure come in handy. If you don't want your privacy violated, you don't need to wait for the Irish privacy regulator to act, you can just install an ad-blocker.

More than half of all web users are blocking ads. But the web is an open platform, developed in the age when tech was hundreds of companies at each others' throats, unable to capture their regulators.

Today, the web is being devoured by apps, and apps are ripe for enshittification. Regulatory capture isn't just the ability to flout regulation, it's also the ability to co-opt regulation, to wield regulation against your adversaries.

Today's tech giants got big by exploiting self-help measures. When Facebook was telling Myspace users they needed to escape Rupert Murdoch’s evil crapulent Australian social media panopticon, it didn’t just say to those Myspacers, 'Screw your friends, come to Facebook and just hang out looking at the cool privacy policy until they get here'

It gave them a bot. You fed the bot your Myspace username and password, and it would login to Myspace and pretend to be you, and scrape everything waiting in your inbox, copying it to your FB inbox, and you could reply to it and it would autopilot your replies back to Myspace.

When Microsoft was choking off Apple's market oxygen by refusing to ship a functional version of Microsoft Office for the Mac – so that offices were throwing away their designers' Macs and giving them PCs with upgraded graphics cards and Windows versions of Photoshop and Illustrator – Steve Jobs didn't beg Bill Gates to update Mac Office.

He got his technologists to reverse-engineer Microsoft Office, and make a compatible suite, the iWork Suite, whose apps, Pages, Numbers and Keynote could perfectly read and write Microsoft's Word, Excel and Powerpoint files.

When Google entered the market, it sent its crawler to every web server on Earth, where it presented itself as a web-user: 'Hi! Hello! Do you have any web pages? Thanks! How about some more? How about more?'

But every pirate wants to be an admiral. When Facebook, Apple and Google were doing this adversarial interoperability, that was progress. If you try to do it to them, that's piracy.

Try to make an alternative client for Facebook and they'll say you violated US laws like the Digital Millennium Copyright Act and EU laws like Article 6 of the EUCD.

Try to make an Android program that can run iPhone apps and play back the data from Apple's media stores and they'd bomb you until the rubble bounced.

Try to scrape all of Google and they'll nuke you until you glowed.

Tech's regulatory capture is mind-boggling. Take that law I mentioned earlier, Section 1201 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act or DMCA. Bill Clinton signed it in 1998, and the EU imported it as Article 6 of the EUCD in 2001

It is a blanket prohibition on removing any kind of encryption that restricts access to a copyrighted work – things like ripping DVDs or jailbreaking a phone – with penalties of a five-year prison sentence and a $500k fine for a first offense.

This law has been so broadened that it can be used to imprison creators for granting access to their own creations

Here's how that works: In 2008, Amazon bought Audible, an audiobook platform, in an anticompetitive acquisition. Today, Audible is a monopolist with more than 90% of the audiobook market. Audible requires that all creators on their platform sell with Amazon's "digital rights management," which locks it to Amazon's apps.

So say I write a book, then I read it into a mic, then I pay a director and an engineer thousands of dollars to turn that into an audiobook, and sell it to you on the monopoly platform, Audible, that controls more than 90% of the market.

If I later decide to leave Amazon and want to let you come with me to a rival platform, I am out of luck. If I supply you with a tool to remove Amazon's encryption from my audiobook, so you can play it in another app, I commit a felony, punishable by a 5-year sentence and a half-million-dollar fine, for a first offense.

That's a stiffer penalty than you would face if you simply pirated the audiobook from a torrent site. But it's also harsher than the punishment you'd get for shoplifting the audiobook on CD from a truck-stop. It's harsher than the sentence you'd get for hijacking the truck that delivered the CD.

So think of our ad-blockers again. 50% of web users are running ad-blockers. 0% of app users are running ad-blockers, because adding a blocker to an app requires that you first remove its encryption, and that's a felony (Jay Freeman calls this 'felony contempt of business-model').

So when someone in a board-room says, 'let's make our ads 20% more obnoxious and get a 2% revenue increase,' no one objects that this might prompt users to google, 'how do I block ads?' After all, the answer is, 'you can't.'

Indeed, it's more likely that someone in that board room will say, 'let's make our ads 100% more obnoxious and get a 10% revenue increase' (this is why every company wants you to install an app instead of using its website).

There's no reason that gig workers who are facing algorithmic wage discrimination couldn't install a counter-app that coordinated among all the Uber drivers to reject all jobs unless they reach a certain pay threshold.

No reason except felony contempt of business model, the threat that the toolsmiths who built that counter-app would go broke or land in prison, for violating DMCA 1201, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, trademark, copyright, patent, contract, trade secrecy, nondisclosure and noncompete, or in other words: 'IP law.'

'IP' is just a euphemism for 'a law that lets me reach beyond the walls of my company and control the conduct of my critics, competitors and customers.' And 'app' is just a euphemism for 'a web-page wrapped enough IP to make it a felony to mod it to protect the labor, consumer and privacy rights of its user.'

We don't care. We don't have to. We're the phone company.

But what about that fourth constraint: workers?

For decades, tech workers' high degrees of bargaining power and vocational awe put a ceiling on enshittification. Even after the tech sector shrank to a handful of giants. Even after they captured their regulators so they could violate our consumer, privacy and labor rights. Even after they created 'felony contempt of business model' and extinguished self-help for tech users. Tech was still constrained by their workers' sense of moral injury in the face of the imperative to enshittify.

Remember when tech workers dreamed of working for a big company for a few years, before striking out on their own to start their own company that would knock that tech giant over?

Then that dream shrank to: work for a giant for a few years, quit, do a fake startup, get acqui-hired by your old employer, as a complicated way of getting a bonus and a promotion.

Then the dream shrank further: work for a tech giant for your whole life, get free kombucha and massages on Wednesdays.

And now, the dream is over. All that’s left is: work for a tech giant until they fire your ass, like those 12,000 Googlers who got fired last year six months after a stock buyback that would have paid their salaries for the next 27 years.

Workers are no longer a check on their bosses' worst impulses

Today, the response to 'I refuse to make this product worse' is, 'turn in your badge and don't let the door hit you in the ass on the way out.'

I get that this is all a little depressing

OK, really depressing.

But hear me out! We've identified the disease. We've traced its natural history. We've identified its underlying mechanism. Now we can get to work on a cure.

There are four constraints that prevent enshittification: competition, regulation, self-help and labor.

To reverse enshittification and guard against its reemergence, we must restore and strengthen each of these.

On competition, it's actually looking pretty good. The EU, the UK, the US, Canada, Australia, Japan and China are all doing more on competition than they have in two generations. They're blocking mergers, unwinding existing ones, taking action on predatory pricing and other sleazy tactics.

Remember, in the US and Europe, we already have the laws to do this – we just stopped enforcing them in the Helmut Kohl era.

I've been fighting these fights with the Electronic Frontier Foundation for 22 years now, and I've never seen a more hopeful moment for sound, informed tech policy.

Now, the enshittifiers aren't taking this laying down. The business press can't stop talking about how stupid and old-fashioned all this stuff is. They call people like me 'hipster antitrust,' and they hate any regulator who actually does their job.

Take Lina Khan, the brilliant head of the US Federal Trade Commission, who has done more in three years on antitrust than the combined efforts of all her predecessors over the past 40 years. Rupert Murdoch's Wall Street Journal has run more than 80 editorials trashing Khan, insisting that she's an ineffectual ideologue who can't get anything done.

Sure, Rupert, that's why you ran 80 editorials about her.

Because she can't get anything done.

Even Canada is stepping up on competition. Canada! Land of the evil billionaire! From Ted Rogers, who owns the country's telecoms; to Galen Weston, who owns the country's grocery stores; to the Irvings, who basically own the entire province of New Brunswick.

Even Canada is doing something about this. Last autumn, Trudeau's government promised to update Canada's creaking competition law to finally ban 'abuse of dominance.'

I mean, wow. I guess when Galen Weston decided to engage in a criminal conspiracy to fix the price of bread – the most Les Miz-ass crime imaginable – it finally got someone's attention, eh?

Competition has a long way to go, but all over the world, competition law is seeing a massive revitalization. Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher put antitrust law in a coma in the 80s – but it's awake, it's back, and it's pissed.

What about regulation? How will we get tech companies to stop doing that one weird trick of adding 'with an app' to their crimes and escaping enforcement?

Well, here in the EU, they're starting to figure it out. This year, the Digital Markets Act and the Digital Services Act went into effect, and they let people who get screwed by tech companies go straight to the federal European courts, bypassing the toothless watchdogs in Europe's notorious corporate crime havens like Ireland.

In America, they might finally get a digital privacy law. You people have no idea how backwards US privacy law is. The last time the US Congress enacted a broadly applicable privacy law was in 1988.

The Video Privacy Protection Act makes it a crime for video-store clerks to leak your video-rental history. It was passed after a right-wing judge who was up for the Supreme Court had his rentals published in a DC newspaper. The rentals weren't even all that embarrassing!

Sure, that judge, Robert Bork, wasn't confirmed for the Supreme Court, but that was because he was a virulently racist loudmouth and a crook who served as Nixon's Solicitor General.

But Congress got the idea that their video records might be next, freaked out, and passed the VPPA.

That was the last time Americans got a big, national privacy law. Nineteen. Eighty. Eight.

It's been a minute.

And the thing is, there's a lot of people who are angry about stuff that has some nexus with America's piss-poor privacy landscape. Worried that Facebook turned Grampy into a Qanon? That Insta made your teen anorexic? That TikTok is brainwashing millennials into quoting Osama Bin Laden?

Or that cops are rolling up the identities of everyone at a Black Lives Matter protest or the Jan 6 riots by getting location data from Google?

Or that Red State Attorneys General are tracking teen girls to out-of-state abortion clinics?

Or that Black people are being discriminated against by online lending or hiring platforms?

Or that someone is making AI deepfake porn of you?

Having a federal privacy law with a private right of action – which means that individuals can sue companies that violate their privacy – would go a long way to rectifying all of these problems. There's a big coalition for that kind of privacy law.

What about self-help? That's a lot farther away, alas.

The EU's DMA will force tech companies to open up their walled gardens for interoperation. You'll be able to use Whatsapp to message people on iMessage, or quit Facebook and move to Mastodon, but still send messages to the people left behind.

But if you want to reverse-engineer one of those Big Tech products and mod it to work for you, not them, the EU's got nothing for you.

This is an area ripe for improvement, and I think the US might be the first ones to open this up.

It's certainly on-brand for the EU to be forcing tech companies to do things a certain way, while the US simply takes away tech companies' abilities to prevent others from changing how their stuff works.

My big hope here is that Stein's Law will take hold: 'Anything that can't go on forever will eventually stop'

Letting companies decide how their customers must use their products is simply too tempting an invitation to mischief. HP has a whole building full of engineers thinking of new ways to lock your printer to its official ink cartridges, forcing you to spend $10,000/gallon on ink to print your boarding passes and shopping lists.

It's offensive. The only people who don't agree are the people running the monopolies in all the other industries, like the med-tech monopolists who are locking their insulin pumps to their glucose monitors, turning people with diabetes into walking inkjet printers.

Finally, there's labor. Here in Europe, there's much higher union density than in the US, which American tech barons are learning the hard way. There is nothing more satisfying in the daily news than the latest salvo by Nordic unions against that Tesla guy (Musk is the most Edison-ass Tesla guy imaginable).

But even in the USA, there's a massive surge in tech unions. Tech workers are realizing that they aren't founders in waiting. The days of free massages and facial piercings and getting to wear black tee shirts that say things your boss doesn't understand are coming to an end.

In Seattle, Amazon's tech workers walked out in sympathy with Amazon's warehouse workers, because they're all workers.

The only reason the tech workers aren't monitored by AI that notifies their managers if they visit the toilet during working hours is their rapidly dwindling bargaining power. The way things are going, Amazon programmers are going to be pissing in bottles next to their workstations (for a guy who built a penis-shaped rocket, Jeff Bezos really hates our kidneys).

We're seeing bold, muscular, global action on competition, regulation and labor, with self-help bringing up the rear. It's not a moment too soon, because the bad news is, enshittification is coming to every industry.

If it's got a networked computer in it, the people who made it can run the Darth Vader MBA playbook on it, changing the rules from moment to moment, violating your rights and then saying 'It's OK, we did it with an app.'

From Mercedes renting you your accelerator pedal by the month to Internet of Things dishwashers that lock you into proprietary dishsoap, enshittification is metastasizing into every corner of our lives.

Software doesn't eat the world, it enshittifies it

But there's a bright side to all this: if everyone is threatened by enshittification, then everyone has a stake in disenshittification.

Just as with privacy law in the US, the potential anti-enshittification coalition is massive, it's unstoppable.

The cynics among you might be skeptical that this will make a difference. After all, isn't "enshittification" the same as "capitalism"?

Well, no.

Look, I'm not going to cape for capitalism here. I'm hardly a true believer in markets as the most efficient allocators of resources and arbiters of policy – if there was ever any doubt, capitalism's total failure to grapple with the climate emergency surely erases it.

But the capitalism of 20 years ago made space for a wild and wooly internet, a space where people with disfavored views could find each other, offer mutual aid, and organize.

The capitalism of today has produced a global, digital ghost mall, filled with botshit, crapgadgets from companies with consonant-heavy brand-names, and cryptocurrency scams.

The internet isn't more important than the climate emergency, nor gender justice, racial justice, genocide, or inequality.

But the internet is the terrain we'll fight those fights on. Without a free, fair and open internet, the fight is lost before it's joined.

We can reverse the enshittification of the internet. We can halt the creeping enshittification of every digital device.

We can build a better, enshittification-resistant digital nervous system, one that is fit to coordinate the mass movements we will need to fight fascism, end genocide, and save our planet and our species.

Martin Luther King said 'It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me, but it can stop him from lynching me, and I think that's pretty important.'

And it may be true that the law can't force corporate sociopaths to conceive of you as a human being entitled to dignity and fair treatment, and not just an ambulatory wallet, a supply of gut-bacteria for the immortal colony organism that is a limited liability corporation.

But it can make that exec fear you enough to treat you fairly and afford you dignity, even if he doesn't think you deserve it.

And I think that's pretty important.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/01/30/go-nuts-meine-kerle#ich-bin-ein-bratapfel/a>

Back the Kickstarter for the audiobook of The Bezzle here!

Image:

Drahtlos (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Motherboard_Intel_386.jpg

CC BY-SA 4.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

-

cdessums (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Monsoon_Season_Flagstaff_AZ_clouds_storm.jpg

CC BY-SA 2.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en

404 notes

·

View notes

Text

For Sander van der Linden, misinformation is personal.

As a child in the Netherlands, the University of Cambridge social psychologist discovered that almost all of his mother’s family had been executed by the Nazis during the Second World War. He became absorbed by the question of how so many people came to support the ideas of someone like Adolf Hitler, and how they might be taught to resist such influence.

While studying psychology at graduate school in the mid-2010s, van der Linden came across the work of American researcher William McGuire. In the 1960s, stories of brainwashed prisoners-of-war during the Korean War had captured the zeitgeist, and McGuire developed a theory of how such indoctrination might be prevented. He wondered whether exposing soldiers to a weaker form of propaganda might have equipped them to fight off a full attack once they’d been captured. In the same way that army drills prepared them for combat, a pre-exposure to an attack on their beliefs could have prepared them against mind control. It would work, McGuire argued, as a cognitive immunizing agent against propaganda—a vaccine against brainwashing.

Traditional vaccines protect us by feeding us a weaker dose of pathogen, enabling our bodies’ immune defenses to take note of its appearance so we’re better equipped to fight the real thing when we encounter it. A psychological vaccine works much the same way: Give the brain a weakened hit of a misinformation-shaped virus, and the next time it encounters it in fully-fledged form, its “mental antibodies” remember it and can launch a defense.

Van der Linden wanted to build on McGuire’s theories and test the idea of psychological inoculation in the real world. His first study looked at how to combat climate change misinformation. At the time, a bogus petition was circulating on Facebook claiming there wasn’t enough scientific evidence to conclude that global warming was human-made, and boasting the signatures of 30,000 American scientists (on closer inspection, fake signatories included Geri Halliwell and the cast of M*A*S*H).

Van der Linden and his team took a group of participants and warned them that there were politically motivated actors trying to deceive them—the phony petition in this case. Then they gave them a detailed takedown of the claims of the petition; they pointed out, for example, Geri Halliwell’s appearance on the list. When the participants were later exposed to the petition, van der Linden and his group found that people knew not to believe it.

The approach hinges on the idea that by the time we’ve been exposed to misinformation, it’s too late for debunking and fact-checking to have any meaningful effect, so you have to prepare people in advance—what van der Linden calls “prebunking.” An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

When he published the findings in 2016, van der Linden hadn’t anticipated that his work would be landing in the era of Donald Trump’s election, fake news, and post-truth; attention on his research from the media and governments exploded. Everyone wanted to know, how do you scale this up?

Van der Linden worked with game developers to create an online choose-your-own-adventure game called Bad News, where players can try their hand at writing and spreading misinformation. Much like a broadly protective vaccine, if you show people the tactics used to spread fake news, it fortifies their inbuilt bullshit detectors.

But social media companies were still hesitant to get on board; correcting misinformation and being the arbiters of truth is not part of their core business model. Then people in China started getting sick with a mysterious flulike illness.

The coronavirus pandemic propelled the threat of misinformation to dizzying new heights. Van der Linden began working with the British government and bodies like the World Health Organization and the United Nations to create a more streamlined version of the game specifically revolving around Covid, which they called GoViral! They created more versions, including one for the 2020 US presidential election, and another to prevent extremist recruitment in the Middle East. Slowly, Silicon Valley came around.

A collaboration with Google has resulted in a campaign on YouTube in which the platform plays clips in the ad section before the video starts, warning viewers about misinformation tropes like scapegoating and false dichotomies and drawing examples from Family Guy and Star Wars. A study with 20,000 participants found that people who viewed the ads were better able to spot manipulation tactics; the feature is now being rolled out to hundreds of millions of people in Europe.

Van der Linden understands that working with social media companies, who have historically been reluctant to censor disinformation, is a double-edged sword. But, at the same time, they’re the de facto guardians of the online flow of information, he says, “and so if we’re going to scale the solution, we need their cooperation.” (A downside is that they often work in unpredictable ways. Elon Musk fired the entire team who was working on pre-bunking at Twitter when he became CEO, for instance.)

This year, van der Linden wrote a book on his research, titled Foolproof: Why We Fall for Misinformation and How to Build Immunity. Ultimately, he hopes this isn’t a tool that stays under the thumb of third-party companies; his dream is for people to inoculate one another. It could go like this: You see a false narrative gaining traction on social media, you then warn your parents or your neighbor about it, and they’ll be pre-bunked when they encounter it. “This should be a tool that’s for the people, by the people,” van der Linden says.

441 notes

·

View notes

Text

(archive)

For Sander Van der Linden, misinformation is personal.

As a child in the Netherlands, the University of Cambridge social psychologist discovered that almost all of his mother’s family had been executed by the Nazis during the Second World War. He became absorbed by the question of how so many people came to support the ideas of someone like Adolf Hitler, and how they might be taught to resist such influence.

While studying psychology at graduate school in the mid-2010s, van der Linden came across the work of American researcher William McGuire. In the 1960s, stories of brainwashed prisoners-of-war during the Korean War had captured the zeitgeist, and McGuire developed a theory of how such indoctrination might be prevented. He wondered whether exposing soldiers to a weaker form of propaganda might have equipped them to fight off a full attack once they’d been captured. In the same way that army drills prepared them for combat, a pre-exposure to an attack on their beliefs could have prepared them against mind control. It would work, McGuire argued, as a cognitive immunizing agent against propaganda—a vaccine against brainwashing.

Traditional vaccines protect us by feeding us a weaker dose of pathogen, enabling our bodies’ immune defenses to take note of its appearance so we’re better equipped to fight the real thing when we encounter it. A psychological vaccine works much the same way: Give the brain a weakened hit of a misinformation-shaped virus, and the next time it encounters it in fully-fledged form, its “mental antibodies” remember it and can launch a defense.

Van der Linden wanted to build on McGuire’s theories and test the idea of psychological inoculation in the real world. His first study looked at how to combat climate change misinformation. At the time, a bogus petition was circulating on Facebook claiming there wasn’t enough scientific evidence to conclude that global warming was human-made, and boasting the signatures of 30,000 American scientists (on closer inspection, fake signatories included Geri Halliwell and the cast of M*A*S*H).

Van der Linden and his team took a group of participants and warned them that there were politically motivated actors trying to deceive them—the phony petition in this case. Then they gave them a detailed takedown of the claims of the petition; they pointed out, for example, Geri Halliwell’s appearance on the list. When the participants were later exposed to the petition, van der Linden and his group found that people knew not to believe it.

The approach hinges on the idea that by the time we’ve been exposed to misinformation, it’s too late for debunking and fact-checking to have any meaningful effect, so you have to prepare people in advance—what van der Linden calls “prebunking.” An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

When he published the findings in 2016, van der Linden hadn’t anticipated that his work would be landing in the era of Donald Trump’s election, fake news, and post-truth; attention on his research from the media and governments exploded. Everyone wanted to know, how do you scale this up?

Van der Linden worked with game developers to create an online choose-your-own-adventure game called Bad News, where players can try their hand at writing and spreading misinformation. Much like a broadly protective vaccine, if you show people the tactics used to spread fake news, it fortifies their inbuilt bullshit detectors.

But social media companies were still hesitant to get on board; correcting misinformation and being the arbiters of truth is not part of their core business model. Then people in China started getting sick with a mysterious flulike illness.

The coronavirus pandemic propelled the threat of misinformation to dizzying new heights. Van der Linden began working with the British government and bodies like the World Health Organization and the United Nations to create a more streamlined version of the game specifically revolving around Covid, which they called GoViral! They created more versions, including one for the 2020 US presidential election, and another to prevent extremist recruitment in the Middle East. Slowly, Silicon Valley came around.

A collaboration with Google has resulted in a campaign on YouTube in which the platform plays clips in the ad section before the video starts, warning viewers about misinformation tropes like scapegoating and false dichotomies and drawing examples from Family Guy and Star Wars. A study with 20,000 participants found that people who viewed the ads were better able to spot manipulation tactics; the feature is now being rolled out to hundreds of millions of people in Europe.

Van der Linden understands that working with social media companies, who have historically been reluctant to censor disinformation, is a double-edged sword. But, at the same time, they’re the de facto guardians of the online flow of information, he says, “and so if we’re going to scale the solution, we need their cooperation.” (A downside is that they often work in unpredictable ways. Elon Musk fired the entire team who was working on pre-bunking at Twitter when he became CEO, for instance.)

This year, van der Linden wrote a book on his research, titled Foolproof: Why We Fall for Misinformation and How to Build Immunity. Ultimately, he hopes this isn’t a tool that stays under the thumb of third-party companies; his dream is for people to inoculate one another. It could go like this: You see a false narrative gaining traction on social media, you then warn your parents or your neighbor about it, and they’ll be pre-bunked when they encounter it. “This should be a tool that’s for the people, by the people,” van der Linden says.

–

Everyone needs to play this game.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

der sich wandelnde "Zeitgeist" sehr schön zusammengefaßt.

Der "Bauer" war im Januar / Februar dieses Jahres dran.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

It has ever been the case that true reforms in the Church have set out from Catholic teaching founded on divine Revelation and authentic Tradition; to defend it, expound it, and translate it credibly into lived life — not capitulation to the Zeitgeist.

from the March 2022 letter of the Bishops' Conference of the Nordic Countries to the German Bishops' Conference.

Original German: Wahre Reformen der Kirche haben seit je darin bestanden, die auf göttliche Offenbarung und authentische Tradition fundierte katholische Lehre zu verteidigen, zu erklären und in glaubwürdige Praxis umzusetzen — eben nicht darin, dem Zeitgeist nachzugehen.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manchmal, in Zeiten in denen ich mich sehr einsam fühle, vermisse ich das „alte“ drei ??? Fandom, sowohl hier auf tumblr, als auch auf anderen Social Media Kanälen, wo man sich einfach austauschen konnte, über sonstige coole Momente, Zitate, usw.

Wenn du heutzutage nicht sofort mit dem Zeitgeist gehst, bist du gleich wieder außen vor. Ich war ein Teil von der TikTok Community, bis man mich wegen angeblich falscher, politischer Ansichten rausgemobbt hat, danke dafür. (Ich bin weder rechts noch links, eigentlich bin ich neutral und fand es eigentlich immer schön, dass das politische aus den drei Fragezeichen weitestgehend rausgehalten wurde.)

Getraue mich manchmal schon gar nicht mehr, manche Sachen zu posten aus Angst vor einer erneuten Hate-Welle…

Alles muss trans, gender und Diversity-gerecht sein, alles wird gleich mal von Grund auf kritisiert, nur weil es von alten, weißen Männern geschrieben wird. Das sind halt nun mal die Autoren, wenn es euch nicht passt, schreibt es doch besser.

Ich shippe auch, zum größten Teil Peter und Bob, aber manches find ich einfach nur noch unangenehm, vor allem weil es nicht mehr so ein Nischenthema ist wie früher, sondern auch die offiziellen Stellen herangetragen wird. Auch das Jens und die anderen Sprecher teilweise nach Veranstaltungen damit belästigt werden, teilweise so penetrant, dass es schon unangenehm ist beim zuschauen.

Grade auf TikTok ist mir das extrem aufgefallen. Auch das Jens und Andreas geshippt werden, finde ich schon grenzwertig.

Das hat nichts mehr mit der Community zutun, in der ich mich einst so wohl gefühlt habe.

Auch wenn es wahrscheinlich niemanden juckt und mir die gleichen Leute an den Hals springen wie vor nem Jahr, aber es musste mal raus.

#die drei fragezeichen#childhood#audio drama#jens wawrczeck#andreas fröhlich#oliver rohrbeck#justus jonas#peter shaw#bob andrews

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ideologisches Wendemanöver: Ford jagt woke Quotenpolitik hinfort

Tichy:»Wer die deutsche Seele kennt, wusste schon seit langem, dass hierzulande die letzte Bastion des ideologischen Wahnsinns unserer Zeit ihre Heimat finden wird. Und während deutsche Autobauer nach Jahren der Anbiederung an den Zeitgeist lieber in den Ruin schlittern, anstatt sich wieder auf eigene Stärken zu konzentrieren, zieht die Karawane in anderen Teilen der Welt

Der Beitrag Ideologisches Wendemanöver: Ford jagt woke Quotenpolitik hinfort erschien zuerst auf Tichys Einblick. http://dlvr.it/TCqMDK «

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hole Is A Band

Jason Cohen, Rolling Stone, 24 August 1995

While the Courtney saga continues, Hole prove that a rock & roll band is the sum of its parts

ERIC ERLANDSON was sitting on a beach in Mexico when the headline caught his eye. Hole's guitarist and co-founder was vacationing with his girlfriend, Drew Barrymore, and thus deliberately out of the loop. After nine months of touring, he was on a much-needed break, his last before the summerlong playground of Lollapalooza. He should have known better. Given that Hole's other founding member is one Courtney Love, Erlandson's blissful, worry-free escape simply wasn't to be. The day-old newspaper beckoned him from across the sand. HOLE SINGER ODS, the headline read. That was all he could make out. His thoughts swirled from annoyance to concern to confidence that everything was surely all right before settling on a slightly jaded "Wouldn't it just figure if Courtney died while I was on vacation?"

A quick look at the story revealed, of course, that Love was just fine. (What was initially reported as an overdose was eventually termed "an adverse reaction to prescription medication.") His worst fears put to rest, Erlandson was skimming the rest of the article when it hit him – a development that was somewhat surprising and most definitely pleasing.

It was the nature of that headline: HOLE SINGER ODS. Not COURTNEY LOVE ODS or GRUNGE WIDOW ODS. Nope. HOLE SINGER.

The circumstances might have been strange and unfortunate, but that headline symbolized some kind of progress. Erlandson had quietly awaited this particular Zeitgeist shift for three years, ever since Hole's music and meaning were firmly subsumed by the irresistible Love star force, with its limitless aura of spectacle, tragedy and provocation.

Conventional wisdom has suggested that a random gathering of cabdrivers, grandmothers and Vanity Fair subscribers would be able to peg Courtney Love in a police lineup, no problem. But no one would be able to pick out mug shots of Erlandson, drummer Patty Schemel or bassist Melissa Auf der Maur, let alone figure out what "Hole" is.

Hole provide a definitive answer in this year's Lollapalooza program book. Paying homage to Blondie, their page is emblazoned with the proclamation, in big rococo letters, that hole is a band. A band that definitely intends – in between Love's inevitable rants, stage dives and column inches – to speak very loudly for itself every night on the Lollapalooza stage.

If Hole's popularity were based only on celebrity, they would have sold a lot more records by now. Instead, with promotion, marketing and life as they knew it shattered by the successive deaths of Love's husband and Hole bassist Kristen Pfaff, Live Through This moved only about 100,000 copies – initially.

Then the freak-show aspect subsided, and after Hole added Auf der Maur they went about the business of playing music. The record topped nearly every '94 critics' poll and – despite never charting higher than No. 52 – was certified platinum in April.

That makes Hole, for the moment at least, the best-selling act on the Lollapalooza main stage, and one gets the feeling Hole would be the chief attraction regardless of sales figures – as was expected, a portion of the Lolla crowd is departing before headliners Sonic Youth take the stage.

Certainly, Hole's million-or-so fan base still includes legions of the merely curious as well as loopily obsessive Love worshipers and kids who see the band as only a legacy. The rest of Hole's audience might feel those things, too, but it also relates intensely to the music.

"The most frustrating thing for me is that people view most female artists as this single person," Erlandson says. "The thing is, I know for a fact that we're more of a band, and we've always been more of a band. I don't want to be in a 'backing band,' and Courtney doesn't want that, either. That's not the way we work."

SO ALLOW ME to introduce you to the four members of the band Hole. Except that I can't, because none of them have materialized in the appointed place (an obscure Manhattan hotel) at the appointed time (3 p.m.). When they do turn up, one of them is missing. We were supposed to conduct a joint interview, something that can't be done without Love, who spends her day shopping and napping.

We regroup in the evening, as the band heads over to Electric Lady Studios to do the syndicated radio show Modern Rock Live. Love walks through the hotel lobby, spraying herself with perfume, and is immediately confronted by two fans. She blows them off cold but not because she's in a bad mood or anything (although she is).

At Electric Lady, Love takes off her shoes, asks Auf der Maur to make room on the couch and Schemel to give her a light, then splays out, feet up, with a book (C. David Heymann's Elizabeth Taylor biography) and a pile of magazines. The TV is on, and Love switches channels to Larry King, whose guest this evening is Barbra Streisand, resplendent in the televised wonders of a Vaseline lens and soft-soft light. "Is that the lighting they're going to give me when I do my Barbara Walters interview?" Love asks. As air time approaches, she tells the band she's cranky and tired and doesn't want to answer all the on-air calls, even if they're directed at her.

After the show we're supposed to take another crack at that four-on-one interview, but Love doesn't feel like it. I'm not too concerned, but Erlandson says he really wants me to observe the full band dynamic. I can't help wondering what he's after. Were they planning a pseudo-orchestrated demonstration of band democracy? Was I going to glimpse a legendary Erlandson-Love blowup? Or perhaps it was just a subtle way for the other three members to say, "Look what we have to put up with!"

I get a big dose of the latter feeling the next day at the photo shoot. Love sleeps the whole way to Coney Island, in New York, in the front seat of the van. Her cosmetician tells me, perhaps indiscreetly, that she prefers it that way come make-up time because a conscious Love is a manic and fidgety Love.

As the day wears on she comes alive again, though during one break she manages a fully clothed half-minute doze right on the beach. Between takes she entertains herself by reading the Globe out loud, saying that tabloid stories are almost always exaggerations of something with a grain of truth in it. It's obviously a subject she knows about. Later she apologizes for putting me off. "I don't want you to think I'm a diva," Love says.

Naturally, Love then proceeds to throw a Kathleen Battle-like fit that's impressive in its steadfastness and serenity. It's nearly 10 p.m., and the band is supposed to have a quick dinner before finishing the shoot. But Love says she's returning to her hotel room for a nap first. There's no tantrum, no argument, no drama, just a sense of "this is the way it's going to be," even though everyone tries to dissuade her.

The overall vibe is how one might imagine things are between Prince and his band mates, albeit with less subservience: a group of distinct, individually talented people responding to its erratic, visionary fireball leader with a slightly patronizing blend of wariness and admiration. "Sure, Prince, whatever you say."

This is not a theory that the members of Hole will confirm for me. All of them are outspoken, bright and funny under ordinary circumstances but a lot more guarded when the subject is Love. "I'm used to it by now," Schemel says. "I accept Courtney exactly, everything she does."

Generally speaking, they brush off Love's unabashed Loveness as part and parcel of the ordinary lead-singer trip. But Love's not your average lead singer. It's kind of like four gorillas saying, "Hey, we're just an ordinary quartet of gorillas. Never mind that one of us weighs 800 pounds."

IF YOU WERE ever to visit Eric Erlandson's hotel room, there would be a 50-50 chance your knock would be answered by a certain well-known actress. You might find this prospect amusing. You might even suspect that the actress would be aware of this and answer the door on purpose.

This is not the case. The reason Drew Barrymore lets me in is because Erlandson is in the bathroom. "Hi, I'm Drew," she says politely, if unnecessarily. The O.J. trial is on the television, and the sweeter-than-you'd-ever-suspect couple tell me they were unnerved to discover attorney Barry Scheck on their flight from Los Angeles. They figured that, karmically speaking, the odds of a crash go up with him on board, and he's not someone you want to share recirculated oxygen with in any case.

Barrymore retreats to the bedroom while Erlandson and I talk. Erlandson is tall and affable with dyed-blond hair that hangs in his eyes and a loose, almost nasal Los Angeles-native drawl. One of seven children in a close-knit Catholic family, he actually hails from San Pedro, Calif., the recently reanointed punk-rock Mecca a half-hour south of L.A.

Erlandson's boyhood paper route included the home of Black Flag guitarist Greg Ginn, but Erlandson missed out on his hometown scene at the time, preoccupied as he was with good old '70s rock.

Now 32, a fact he gives away freely but sheepishly, Erlandson was a late bloomer. He attended college at Loyola Marymount, where his father was a dean, and also held down an accounting job at Capitol Records. Then he caught the punk-rock bug. "I started late," Erlandson says. "I didn't really experiment with anything bad for you until I was 27."

What exactly happened when you were 27? Fall in with some kind of "bad girl," didja?

Erlandson laughs. "Yeah, you could say that," he says.

You could, and Love frequently does, announcing from the stage, "Eric was my boyfriend once. He won't admit it 'cause I'm too ugly." She also refers to him as Eric Barrymore. He usually responds to this by giving her the finger, if he responds at all.

Erlandson is a soft-spoken sort, the steely guitarist who's content simply to make his music and hit the town with his (very young, movie-star) girlfriend. Within the band he's known as the Archivist, the guy who keeps track of all the live tapes and jam sessions. On a musical level he's the guy who really gives the songs their crackle. He played most of the guitars on Live Through This, while Love concentrated on lyrics and vocals.

Like Love, Erlandson is a Buddhist, though after she introduced him to the religion he became the more devout practitioner. All in all, unlikely rock-star material, but then, what fame Erlandson has is not entirely his own.

"Yeah, it's ironic," he says. "The two people in my life are like these people that are everywhere. It's pretty sick for me to go to a newsstand." (At the time, Barrymore's Rolling Stone cover was out, as was Love's Vanity Fair.)

Erlandson met Love in 1989 when he answered a free classified ad (no, not the personals – the MUSICIANS WANTED) she'd placed. "She called me up and talked my ear off, and I was like 'Who the hell was that?'" Erlandson recalls. "We met at this coffee shop, and I saw her and I thought, 'Oh, God, oh, no, what am I getting myself into?' She grabbed me and started talking, and she's like 'I know you're the right one!' And I hadn't even opened my mouth yet."

There were many false starts, but what basically kept them together was a love of god-awful clattering. "We were one big, screaming mess," Erlandson says. "I was just like 'OK, this is cool, this is noise.' I was always into the No Wave thing, but it never caught on in L.A. I was like 'Wow, I finally found someone who's into doing this stuff.'"

A pair of singles followed, one of which was on Sub Pop, and then came 1991's Pretty on the Inside, co-produced (with Don Fleming) and heavily influenced by Sonic Youth's Kim Gordon.

What's often forgotten is that Pretty on the Inside was pretty well-received and not a half-bad record. Love's vividly scabrous lyrical tone – part self-immolation, part outwardly directed paroxysm – was well established, and beneath the cruddy goth-punk caterwauling there were hints of New Wave sense and songcraft sensibility.

The band on that record – Love, Erlandson, drummer Caroline Rue and bassist Jill Emery – didn't last very long, but even through the period in which Love was most famous for whom she loved, Hole got it back together. In 1992, Erlandson and Love signed with DGC/Geffen and eventually roped in Patty Schemel.

The first thing I learn about Schemel is that she gets cranky when she hasn't eaten in a while, which is why we head for an Italian restaurant. As she digs into some gnocchi, we chat about supermodels; she's particularly fond of Kristen McMenamy. When Schemel is done eating, New York's new anti-smoking law forces her to step outside.

Auf der Maur is along as well, as is Schemel's girlfriend, Stacey, who in a touching testament to the faith and folly of mixing business with romance also works as Love's assistant. Merely for her platinum hair, Stacey is always mistaken for either Barrymore or Love by people on the street. Schemel recently got her own apartment in Seattle, but during the past year, when the band wasn't on tour, she was living with Stacey at Love's house. The band was almost always on the road, though. And it's a big house.

Schemel's parents were New Yorkers who still have the accents to prove it, but they moved to Marysville, Wash. (about an hour north of Seattle), before she was born. Dad still works for Pacific Bell; Mom was at GTE ("We're a communications family," Schemel says). Schemel took up the drums when she was 11 "because it was something girls didn't do," she says, and to this day her mother still complains that Schemel doesn't project enough good cheer when she plays.

"We played this show, and my mom is up in the VIP balcony hanging over the edge, waving, like 'Smile!'" Schemel says with a laugh. "Flashback, I'm 11 again, playing the school recital. After Unplugged, she called and said, 'Not much smiling, but you sounded great.'"

Otherwise, Schemel says, her parents were always supportive of both her music and her sexuality. "My dad was always instilling that if you can do your art, your passion, and also get paid to do it, that it's a great accomplishment." The rest of Marysville wasn't so accommodating on either front.

"There were all these cowboys, and then there were rockers – no punk rockers," Schemel recalls. "Punk rock was a good place to go where there were other people who felt like me."

Seattle beckoned. The only genuine Rock City scenester in Hole, Schemel ran with such nascent luminaries as Sub Pop honcho Bruce Pavitt, checking out the pre-grunge scene and forming a band called Sybil with her younger brother. They didn't get very far, but Schemel established her reputation as one of the city's best drummers. She would have to be, what with that tattoo of John Bonham's rune (the triple circle) on her arm.

Schemel's only mistake was missing out entirely on the local explosion. When Erlandson and Love tracked her down in 1992, she was living in San Francisco, where she'd moved two years before, "thinking that was the next big city," Schemel says. She tried out for Hole on her 25th birthday and spent the rest of the year learning the old songs and feeling out new ones with Erlandson.

Given the varied psychosexual meanings implicit in Hole's existence, Schemel adds an extra dimension to the mix. Hole have something for everybody, regardless of gender, preference, fetish or taste. Schemel's not on a pedestal about it, but she says it feels good to be a role model in a band that connects so profoundly with its audience.

"It's important," she says. "I'm not out there with that fucking pink flag or anything, but it's good for other people who live somewhere else in some small town who feel freaky about being gay to know that there's other people who are and that it's OK."

MELISSA AUF DER Maur is sitting at the bar of the alterna-hip New York watering hole Max Fish. Melissa Auf der Maur is also on the wall of the Lower East Side hangout. See, a year ago, Melissa Auf der Maur – OK, so a simple she would probably suffice at this point, but what fun would that be? – was just a third-year photography student playing in a Canadian indie-rock band, and tonight one of her many self-portraits is part of an exhibit here.

Auf der Maur was quite happy back in Montreal, too, which is why when Smashing Pumpkin Billy Corgan told her she should try out for Hole, she thought he was out of his mind. This is probably what sealed her fate, at least from Love's point of view.

"Billy was going on about this hot babe who could really play, and I was like 'Yeah, right, you're giving her the girl leeway,' because Billy is sort of a pig," Love says. "But I thought I would try her out, and I pursued her a little bit, and what I thought was hot was that she said no. I thought that was really cool."

"That's a thing to like, I guess," Auf der Maur deadpans. "That's attractive. Yeah, I was just, like, in my space, in my life, with my band. I had been at the New Music Seminar handing out my demo tapes and putting my 7-inch together. I was like 'No way, I've got my life – what, you think I wanna leave my life?'"

Soon enough, however, she realized it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, so she went to Seattle to audition. Two weeks later, she was playing in front of 80,000 people at the 1994 Reading Festival. "I felt nothing," she says. "I was like 'This is just a reflection of what I'm about to do with my life.'"

Only 23 years old, Auf der Maur had already led something of a storybook life before joining Hole. Her mother was never married to her father ("She barely knew the guy") and was living with Frank Zappa (platonically) during the pregnancy. Mother and daughter spent their first two years together in Africa and London, living with a zoologist friend. Dad, meanwhile, is a high-profile Montreal politician and journalist.

"For my entire life I was Nick Auf der Maur's daughter, and all of a sudden he's Melissa Auf der Maur's father," she says. "He gets such a kick out of it, that little kids are reading his name."

If Love is, for better or worse, the aggressive female role model of the band, then Auf der Maur would be the favorite of Hole's Y-chromosome following. Apparently she attracts crushes the way Love attracts headlines. "She's amazing," Schemel marvels. "So many boys, it's like, God." It's not too difficult to figure out why: While Auf der Maur is self-possessed enough to compare herself (convincingly) to Botticelli's Birth of Venus in her self-portraits, she's so graceful and open that there's nothing off-putting about her.

"Melissa's like a well-bred, quiet, pretty version of me at her age," Love says, though it's unclear what exactly would be left of Love with those caveats. "She's a bit of a Heather. Everyone else is a geek. Patty was like a chosen geek, and me and Eric were born geeks, but Melissa's well mannered and ethereal and very spiritual, but she only knows about astrology."

That actually helped Auf der Maur before the audition. "Before I met them, Eric called me up, and he's like 'I have three questions to ask you,'" Auf der Maur says. "One: 'Are you a drug addict?' No, far from it. Two: 'Do you play with a pick?' Yes. And three: 'What sign are you?' Pisces. And Pisces being the most emotionally full sign, it was perfect. I'm definitely drawn to emotionally full situations, so it made sense to me. I've always been told that I'm too sensitive or too aware of other people's things, so I was like 'Well, finally I'm going to be able to use that to my advantage.'"

"IF YOU'RE GONNA sit here and call that a valentine, I'm gonna kick your ass!"

At long last I've been granted my audience with Love, and I've made the innocent mistake of uttering the words Vanity Fair. Apparently she's a bit sensitive to charges that her recent VF cover story was, shall we say, clean – so clean that Love's breasts were likened to "great cakes of soap." I'm told that if I want to see a real valentine, I should reread this magazine's Drew Barrymore piece. "That girl will never need toilet paper again in her fucking life," Love gripes.

It's safe to assume that Love and Erlandson and Barrymore don't spend a lot of Saturday nights together renting movies and popping popcorn. What's irritating, though, is the way Love's self-made feminist iconoclasm leaves room for an old-fashioned cattiness that borders on misogyny, usually directed at people who aren't dissimilar to her – such as Barrymore or her old friend Kat Bjelland from Babes in Toyland or a laundry list of female rock critics who've faced the same sexist groupie stigma Love has.

But everything that Love does is half acting out, half conscious manipulation and half practical joke. (Yeah, that's three halves, but who says Love adds up?) She's astoundingly intelligent, maddeningly contradictory and a total force of nature – it's exhausting just being in a room with her.

"I fake it so real I am beyond fake," goes the oft-quoted lyric from 'Doll Parts', and it's clear the line was meant to resonate at every possible level – as truth, as irony and as a mockery of both herself and her audience. With Love it's a question of how much she can get away with and how much she decides to give away.

Take Jeff Buckley, for instance. Right now you're probably thinking to yourself, "How did Jeff Buckley get into the middle of this Hole story?" Relax – there's an answer to every question, and you can't very well have a Hole story without the presence of at least one cute and slightly famous rocker boy.

Buckley has been on Love's mind a bunch the last couple of days. Supposedly, Auf der Maur met him in Canada and has what Love calls "a minicrush on him. I'm just sort of putting her in her place." So Buckley and Love have been trading phone calls and answering machine messages, trying to get together – friendlylike, don't get any ideas. And most of these phone calls have been made in front of me, the unobtrusive, all-seeing journalist. And Love... well, she's not the type of person who does things in front of the media by accident.

Now we're in the middle of our interview, and time is at a premium because Love intends to catch the Broadway production of Hamlet with her prospective pal. So she calls him two or three more times in front of me to nail down the plans. And then he comes to her hotel room while I'm still there. And then they go to Hamlet, and brilliantly, Love stops to ask directions from – get this – a professional photographer. By intermission – go figure! – the paparazzi are already about.

In the next couple of weeks, the nonexistent couple gets items in USA Today, the New York Post and People. Buckley ends up being thoroughly freaked out by the experience – so much so that he calls me from England to try to clear his name. Buckley is a sensitive sort and more than a little naive. "Who the fuck am I?" he wanted to know. "I'm not like a Dando. I went out for one night, and I'm thrust into this weird, rock-star charade heavy thing." He feels used.

"Y'know," Love had said to me before Buckley came to pick her up that night, "sometimes I would love to just put out my music and have people leave me alone so I could go to see Hamlet with Jeff Buckley, and you might not hear a word about it."