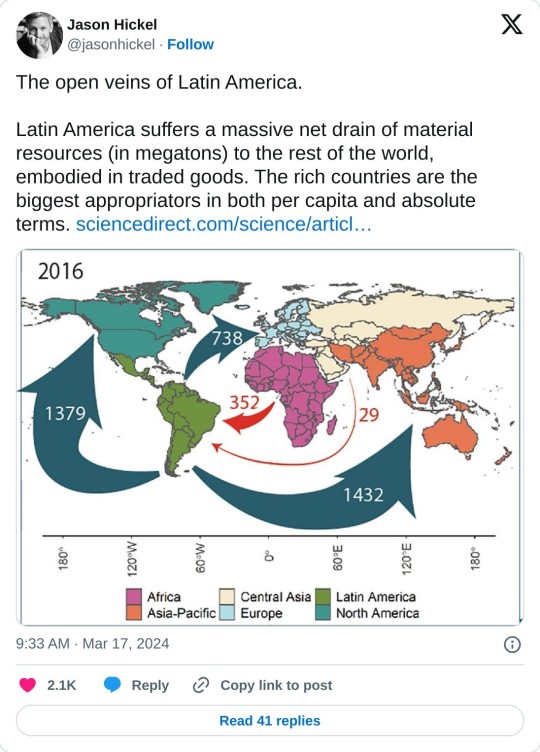

#ecologically unequal exchange

Text

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

[ me ]

potential big issues

land allocation - land values are pretty unequal; the original thinking actually split land into "urban" and "rural" allocations, but that probably isn't enough to resolve this

[ @thathopeyetlives ]

That's definitely not enough to resolve this -- I think you need, at a minimum, "farmland", "wasteland/desert" and "forest/intermediate" allocations.

I wanted to see what "universal basic land" would look like after sev proposed "universal basic landed aristocracy."

The population mechanism I discussed (splitting land allocation with children, distributing allocation to all on death) doesn't have a good name. It trades away the assumption of a life-supporting minimum allocation in exchange for doing away with direct fertility controls. It's not "universal basic." But before I devised that, I sketched out how a "universal basic land" might work for a faction in a sci-fi setting.

If we're thinking of land as a basic support for life (as opposed to a basic income as a basic support for life), then we're talking about its life-sustaining power, which is related to its agricultural yield (insolation, rainfall, soil conditions, etc). So we think in terms of homesteading (amount required to support one healthy person if they farm it, plus a margin) to determine the size of the land allocated, even if we don't expect the land to be homesteaded, plus a reserve for ecology (to provide oxygen & other environmental services).

In that model, we get a smooth gradation from "wasteland" through "farmland".

In the proposal, people could swap parcels of land but not own more than the total allocation. They could offer payment for the swap - land would have value, and you could even accumulate land-value, but you couldn't accumulate the land itself (and thus monopolize its life-sustaining power).

For a more contemporary setting, farming isn't the dominant mode of employment, and we probably need to treat rural or agricultural land as a separate category from urban land so as to avoid disruption of food production systems - many people are stupid and might try to extort too high a rent for farmland, or might try to block farming, etc. In a homestead setting and one in which everyone comes from a homestead background or culture, people would have a much better understanding of the land and its production so that would be of less concern. (A long-term transition would involve the government buying out land as people die and putting it into the allocation pool.)

I think there's a lot more work to do on it than that, though. (And of course no arrangement of the variables generates enough for everyone to survive for free without doing any notable work.)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cultural Homogenization, Cultural Hybridization, Cultural Heterogenization

In the era of globalization, cultural interactions, and exchanges have become more prevalent, leading to various processes that shape the global cultural landscape. Three key concepts that arise in discussions about these processes are cultural homogenization, cultural hybridization, and cultural heterogenization. While these terms may sound similar, they represent distinct phenomena that reflect different dynamics of cultural interaction and change. In this article, we will explore and compare cultural homogenization, cultural hybridization, and cultural heterogenization to gain a deeper understanding of their meanings and implications.

I. Cultural Homogenization: The Loss of Diversity

Cultural homogenization is a complex process that results in the diminishing or erasure of cultural differences and the emergence of a more standardized and uniform global culture. This phenomenon is primarily driven by the dominance and diffusion of certain cultural practices, values, and products, often facilitated by the forces of globalization. Understanding the various aspects of cultural homogenization provides insight into its impact on societies worldwide:

Globalization and Cultural Dominance

Globalization, characterized by increased interconnectedness and the rapid exchange of information and media, plays a significant role in cultural homogenization. The advancements in transportation, communication, and technology have facilitated the widespread dissemination of cultural products, ideas, and values. This interconnectedness has enabled dominant cultures to exert influence on a global scale. Western culture, particularly American culture, has been at the forefront of this cultural dominance, shaping global norms, consumerism, and popular culture.

Standardization and Loss of Traditional Practices

One consequence of cultural homogenization is the loss of traditional practices. As dominant cultural practices spread, local customs and traditions may be marginalized or overshadowed. Traditional rituals, ceremonies, and artistic expressions that once defined the uniqueness of specific cultures can become diluted or even vanish entirely. This loss of traditional practices can erode cultural diversity, as societies increasingly adopt standardized ways of living and engaging with the world.

Language and Cultural Identity

Cultural homogenization also affects language diversity and cultural identity. Language is an essential aspect of cultural expression and identity. With the dominance of certain languages, particularly English, there is a risk of indigenous and minority languages facing extinction. When languages disappear, significant cultural knowledge, oral traditions, and worldviews are lost. The erosion of linguistic diversity is closely tied to the weakening of cultural identities, as language often serves as a vital vehicle for preserving and transmitting cultural heritage.

Marginalization of Local Cultures and Indigenous Knowledge

The rise of global cultural forces can marginalize local cultures and indigenous knowledge systems. As dominant cultural practices gain prominence, they may overshadow or devalue local cultural expressions, beliefs, and knowledge. Local communities that have historically relied on their unique cultural practices and ecological knowledge to sustain their livelihoods and maintain harmonious relationships with their environments can face challenges when confronted with globalized systems and practices. This marginalization not only diminishes cultural diversity but can also disrupt the social fabric and well-being of these communities.

Cultural Imperialism and Power Dynamics

Critics of cultural homogenization argue that it can lead to cultural imperialism, where powerful cultures impose their values, norms, and practices on others. The dominance of a few cultures can create unequal power dynamics, with the cultural expressions and identities of marginalized groups being subjugated or diminished. This can result in the erosion of local traditions, weakened cultural autonomy, and a loss of self-determination. The impact of cultural imperialism extends beyond cultural diversity and can influence various aspects of society, including politics, economics, and social structures.

Examples of Cultural Homogenization

- The spread of fast-food chains, such as McDonald's or Starbucks, across the globe, led to the proliferation of standardized dining experiences and the marginalization of local culinary traditions.

- The global popularity of Hollywood films, which often reflect Western cultural values, narratives, and aesthetics, influences film industries worldwide and shapes audience preferences.

- The dominance of the English language as the lingua franca of business, education, and international communication, potentially marginalizes other languages and cultural perspectives.

- The adoption of Western fashion trends and styles, such as wearing jeans or T-shirts, as symbols of modernity and cosmopolitanism, often at the expense of traditional clothing and craftsmanship.

II. Cultural Hybridization: Blending and Synthesis

Cultural hybridization is a dynamic process that emphasizes the blending and synthesis of different cultural elements and influences. It occurs when diverse cultures come into contact and engage with one another, leading to the creation of new cultural forms and expressions. Cultural hybridization recognizes the agency and creativity of individuals and communities in actively shaping the cultural influences they encounter. Understanding the various aspects of cultural hybridization provides insights into its manifestations and significance:

Fusion of Traditional and Contemporary Elements

Cultural hybridization often involves the fusion of traditional and contemporary elements. When cultures interact, traditional practices and values can be combined with modern influences to create unique expressions. For example, in music, artists may incorporate traditional instruments and melodies into contemporary genres, producing hybrid musical styles that blend cultural heritage with modern sounds. This fusion of traditional and contemporary elements enables the preservation and reinterpretation of cultural traditions within evolving cultural landscapes.

Local and Global Influences

Cultural hybridization reflects the interplay between local and global influences. As cultures encounter external ideas, practices, and products, they adapt and integrate them into their own cultural frameworks. This process allows for the creation of unique cultural expressions that reflect both local sensibilities and global influences. For instance, in the realm of cuisine, fusion restaurants and culinary innovations often combine local ingredients and cooking techniques with international flavors and culinary traditions, resulting in new gastronomic experiences.

Merging of Cultural Practices from Different Regions

Cultural hybridization also involves the merging of cultural practices from different regions. When cultures interact, they may borrow, adapt, or blend practices from one another, leading to the emergence of new cultural phenomena. For example, martial arts forms such as Brazilian Capoeira and American Krav Maga have roots in diverse cultural traditions but have undergone transformations and adaptations over time, resulting in unique hybrid martial arts styles. This blending of practices not only showcases cultural exchange but also fosters cross-cultural understanding and appreciation.

Hybrid Languages and Linguistic Expressions

Language and linguistic expressions are significant components of cultural hybridization. When different linguistic communities interact, new hybrid languages may emerge. These languages often blend vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation from multiple sources, reflecting the multicultural nature of their speakers' experiences. Pidgin languages, such as Nigerian Pidgin English or Singlish in Singapore, are examples of linguistic hybridization, combining elements of various languages to facilitate communication between different communities.

Cultural Hybridity and Identity Formation

Cultural hybridization plays a role in the formation of individual and collective identities. As cultures intertwine, individuals and communities navigate between their cultural heritage and the influences they encounter. Cultural hybridity allows individuals to shape their identities by selectively adopting, adapting, and reinterpreting cultural elements. It enables individuals to express their multiple affiliations and identities, leading to the emergence of diverse and complex identity formations.

Examples of Cultural Hybridization

- The emergence of Afro-Cuban jazz, which combines African rhythms and instruments with elements of American jazz, created a unique and distinct musical style.

- The fashion industry's incorporation of traditional textiles and patterns from different cultures into contemporary designs led to the creation of fusion fashion that celebrates cultural diversity.

- The fusion cuisine of Peruvian-Japanese Nikkei cuisine, blends traditional Peruvian ingredients and cooking techniques with Japanese flavors and culinary traditions, resulting in a unique gastronomic experience.

- The development of Spanglish, a hybrid language that combines Spanish and English, is commonly spoken by bilingual communities, particularly in regions with significant Hispanic populations.

III. Cultural Heterogenization: Coexistence and Fragmentation

Cultural heterogenization is a concept that underscores the coexistence of diverse cultural expressions, practices, and identities within a specific context. It recognizes that in an increasingly interconnected world, cultural differences persist and continue to shape both local and global experiences. Unlike cultural homogenization or hybridization, cultural heterogenization emphasizes that cultures do not blend or merge into a singular global culture, but rather coexist, often in fragmented and localized forms. Within the framework of cultural heterogenization, several key aspects can be explored:

Preservation of Traditional Cultural Practices

One aspect of cultural heterogenization is the preservation of traditional cultural practices. Despite the influences of globalization, many communities around the world actively work to maintain their unique cultural heritage. Traditional ceremonies, rituals, art forms, and craftsmanship are preserved and passed down through generations, serving as a testament to the enduring significance of cultural diversity. These practices often play a vital role in fostering a sense of identity, community cohesion, and intergenerational transmission of cultural knowledge.

Maintenance of Distinct Local Identities

Cultural heterogenization also involves the maintenance of distinct local identities. In the face of globalization, communities strive to preserve their cultural identity and assert their unique characteristics. Local traditions, languages, dialects, and customs play a pivotal role in shaping the identity of specific regions or ethnic groups. These distinct identities may be reinforced through cultural festivals, folklore, traditional clothing, cuisine, and other forms of cultural expression. By nurturing and celebrating these local identities, communities can resist the pressures of cultural assimilation and maintain their cultural distinctiveness.

Formation of Subcultures and Countercultures

Another aspect of cultural heterogenization is the emergence of subcultures and countercultures. Subcultures refer to smaller groups within a larger society that share distinctive beliefs, values, practices, and styles that differentiate them from the mainstream culture. These subcultures often form around specific interests, such as music genres (e.g., punk, hip-hop, or heavy metal), fashion movements, or artistic expressions. Countercultures, on the other hand, challenge or resist the dominant cultural norms and values of society. They represent alternative ways of living and thinking and may advocate for social change or critique mainstream ideologies. Subcultures and countercultures contribute to cultural heterogenization by providing spaces for self-expression, fostering alternative perspectives, and promoting diversity within society.

Localized Cultural Expressions

Cultural heterogenization is also reflected in the proliferation of localized cultural expressions. While global cultural influences may permeate various societies, local adaptations and interpretations shape how these influences are manifested. Localized forms of music, art, literature, and popular culture emerge, blending global trends with local contexts and sensibilities. This localization allows for the preservation of cultural diversity and the expression of unique regional or community-specific identities.

Fragmentation and Diversity

In the context of cultural heterogenization, fragmentation is an important concept to consider. While cultural diversity persists, it can lead to fragmentation, where cultures become more distinct and separate from one another. This fragmentation can occur at different levels, ranging from regional variations within a country to the preservation of indigenous cultures that resist assimilation into mainstream society. Fragmentation can contribute to the richness of cultural expression and the resilience of cultural diversity.

IV. Understanding the Interplay of Cultural Dynamics

It is essential to understand the nuances and interplay of these cultural dynamics in the context of globalization. Cultural homogenization, cultural hybridization, and cultural heterogenization are not mutually exclusive but rather coexist and interact in complex ways.

While cultural homogenization may pose challenges to cultural diversity, it is crucial to recognize that cultural hybridization and cultural heterogenization can also arise as responses to cultural homogenization itself. Cultural hybridity can be seen as a form of resistance and creativity that emerges in the face of dominant cultural forces, while cultural heterogenization highlights the ongoing existence and resilience of diverse cultural expressions.

By acknowledging these dynamics, we can foster a more nuanced understanding of the complexities of cultural interactions in a globalized world. Embracing cultural hybridity and preserving cultural heterogenization can provide avenues for cultural preservation, intercultural dialogue, and the celebration of diverse cultural expressions.

In conclusion, cultural homogenization, cultural hybridization, and cultural heterogenization represent different aspects of global cultural interactions. Cultural homogenization involves the loss of diversity, cultural hybridization emphasizes blending and synthesis, and cultural heterogenization highlights the coexistence and fragmentation of diverse cultural expressions. These concepts offer insights into the complex dynamics of cultural change, diversity, and identity formation in the context of globalization.

V. Reference Links:

- Appadurai, A. (1990). "Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy." Public Culture, 2(2), 1-24. Link

- García Canclini, N. (1995). Hybrid Cultures: Strategies for Entering and Leaving Modernity. University of Minnesota Press.

- Hannerz, U. (1992). Cultural Complexity: Studies in the Social Organization of Meaning. Columbia University Press.

- Pieterse, J. N. (1995). "Globalization as Hybridization." International Sociology, 10(2), 161-184. Link

- Robertson, R. (1992). Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture. SAGE Publications.

- Tomlinson, J. (1999). Globalization and Culture. Polity Press.

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

The Versatile Marvel: Discovering the Conveniences of Titanium Tubes

Introduction:

Titanium, renowned for its exceptional stamina, low density, and corrosion resistance, is an amazing metal that finds substantial applications in various sectors. Among its many types, titanium tubes stand apart as a functional solution, providing a series of benefits that add to exceptional performance as well as durability. In this article, we will certainly delve into the countless benefits of titanium tubes, highlighting their distinct residential or commercial properties, applications, as well as the positive impact they have in varied fields.

Titanium Tube

Unequaled Strength-to-Weight Ratio:

One of the most substantial advantages of titanium tubes is their phenomenal strength-to-weight ratio. Titanium possesses impressive stamina equivalent to many steels, while being virtually 50% lighter. This home makes titanium tubes optimal for applications where weight decrease is critical, such as aerospace components, auto components, and also showing off devices. The lightweight nature of titanium tubes enables improved gas efficiency, enhanced maneuverability, as well as raised total efficiency in various markets.

Superb Rust Resistance:

Titanium is very immune to deterioration, also in rough environments. Its natural oxide layer acts as a safety obstacle, making titanium tubes remarkably immune to rust from wetness, chemicals, and saltwater. This corrosion resistance is invaluable in industries such as aquatic, offshore oil and also gas, chemical handling, as well as desalination plants. By utilizing titanium tubes, business can substantially lower maintenance costs, expand devices lifespan, as well as guarantee dependable efficiency in corrosive conditions.

Titanium Sheet

Superb Thermal Stability:

Titanium displays exceptional thermal security, permitting it to hold up against severe temperatures without deformation or loss of mechanical properties. This residential property makes titanium tubes excellent for applications that include high-temperature settings, such as warmth exchangers, power generation, as well as aerospace systems. Titanium tubes can successfully hold up against both reduced as well as heats, making certain trustworthy performance as well as sturdiness popular thermal problems.

Biocompatibility as well as Medical Applications:

The biocompatibility of titanium is an essential advantage that makes it extensively utilized in the clinical field. Titanium tubes are extensively utilized in the manufacture of clinical implants, such as joint substitutes, dental implants, and back blend tools. Its biocompatibility ensures compatibility with human tissues, minimizing the threat of being rejected or unfavorable reactions. In addition, titanium's deterioration resistance and outstanding strength-to-weight ratio make it an ideal selection for clinical tools that call for lasting durability and efficiency.

Outstanding Conduit for Liquids and also Gases:

Titanium tubes supply outstanding conductivity properties, making them very ideal for sharing liquids and also gases. Their smooth internal surface allows for effective circulation with marginal frictional losses. This building is beneficial in applications such as heat exchangers, oil as well as gas pipelines, chemical processing, as well as desalination plants. Titanium tubes guarantee optimum flow prices, decrease power usage, and keep the stability of delivered liquids or gases.

Durability and Price Financial Savings:

As a result of their outstanding deterioration resistance as well as durability, titanium tubes have a substantially longer life expectancy contrasted to other materials. Their resistance to wear, exhaustion, and ecological destruction reduces the demand for constant substitutes as well as maintenance. This longevity translates right into expense savings for industries, as they can prevent expenditures connected with tools failures, downtime, as well as substitute parts. The long-lasting longevity of titanium tubes adds to improved operational performance as well as minimized lifecycle expenses.

Conclusion:

Titanium tubes offer a myriad of advantages that make them an invaluable product in numerous sectors. From their extraordinary strength-to-weight ratio and corrosion resistance to their thermal security and also biocompatibility, titanium tubes offer unrivaled efficiency as well as integrity. Whether in aerospace, automotive, clinical, or industrial applications, titanium tubes contribute to enhanced efficiency, resilience, and expense savings. As industries remain to push the limits of innovation, titanium tubes will stay an important element, empowering advancements across several sectors.

0 notes

Text

Bitcoin hits new all-time high as crypto market surges in bull run

Bitcoin, the world's most important cryptographic money, as of late hit another unequaled high, taking off to more than $ per coin. This denotes a momentous circle back from only a couple of years prior when Bitcoin was viewed as a specialty resource with little standard allure.

The new flood in Bitcoin's cost is essential for a more extensive bull run in the cryptographic money market, which has seen other famous computerized monetary standards like Ethereum, Lite coin, and Wave likewise experience huge additions in esteem. While certain specialists caution that the ongoing business sector free for all may not be feasible, numerous others accept that digital currencies are ready for proceeded with development and long haul achievement.

One of the critical drivers of the new cryptographic money flood has been the developing institutional premium in computerized resources. Major monetary foundations like Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, and Morgan Stanley bring all as of late declared plans to the table for digital currency venture items to their clients, and a few enormous organizations, including Tesla, Square, and PayPal, have likewise started tolerating Bitcoin as a type of installment.

Another element driving the cryptographic money blast is the rising acknowledgment of computerized resources as a genuine store of significant worth and speculation vehicle. Numerous financial backers are going to cryptographic forms of money as a method for supporting against expansion and safeguard their riches, especially despite uncommon financial upgrade from states all over the planet.

Regardless of the developing ubiquity of digital currencies, they stay an exceptionally unpredictable and speculative resource class, likely to sharp swings in esteem in view of market opinion and financial backer way of behaving. This instability has prompted worries among certain controllers and policymakers, who stress that the cryptographic money market could represent a gamble to monetary soundness.

Because of these worries, a few nations have done whatever it takes to intently control digital forms of money more. China, for instance, as of late taken action against Bitcoin mining and exchanging, referring to worries about the ecological effect of digital money digging and the potential for monetary shakiness.

Regardless of these difficulties, the fate of digital currencies looks splendid. With developing institutional help and expanding standard acknowledgment, it appears to be probable that advanced resources will keep on assuming an undeniably significant part in the worldwide monetary scene in the years to come. Whether the ongoing cryptographic money blast is maintainable is not yet clear, yet one thing is clear: Bitcoin and other advanced monetary forms are staying put.

FOR MORE INFO :-

crypto market news

0 notes

Text

Explaining the environment through chemical elements and physics is like discovering American continent.

I am not fond of Nobel prize is only a modesty and image.

Now we discovered everything we have all patents why can't we live more happily?

Because is not finished the discovery of genetics natural processes mechanism the law of nature has been neglected by industrial physicists.

How many people celebrities should win the Nobel prize?

I just don't want abuse of my intellectual property you win as much as you want.

I have two new point on oxygen deficiency or unequal distribution bonding and the effects that I've mentioned to prosper transportation.

One point from earlier discoveries on temperature. Can an environment change temperature ecologically

Make cold places warmer and warm places cooler by few degrees

I think this is linked to oxygen exchange in microbial life

🤺🇬🇧

0 notes

Text

Journal No. 1

Own Idea and Perceptions on Globalization

Observation

"Globalization" is the 21st century's favorite buzzword. It is an integral part of growing countries' interdependence in terms of economies, cultures and populations brought by the cross-border trade in goods and services, technology, workforce. Today, Globalization is in its ultimate form. The fast-developing electronic commerce or e-commerce has been the gateway to the development of transportation across borders, progressive removal of barriers to trade; enabling people to buy products at a lower price and ultimately, it helps alleviate countries' economic performance. And although we know Globalization as a modern-day concept, the unflagging truth is it has always existed. Dating back to Middle Ages, Central Asia was connected to China and Europe via the famous Silk Road. After World War II and the last two decades, governments of many countries have adopted free-market economies (Vanham, n.d.). This kick start the international trade and investment – what we know as Globalization.

For many of us, Globalization has had a lot of positive effects in the world. But to another group of people, it can be a serious cause of destruction in the ecology, a cause of inequality in society, reason for unequal growth in economy, a digital divide, and a loss of power in a nation-state level.

Insight

The impact of Globalization has been both positive and negative. I personally wouldn't wish Globalization hadn't existed even if there are negative effects to it because I believe that Globalization is continually improving, and it is up to us to find ways on how we can shape and mold it to cater to the needs of our world – of our generation. We can offer a fairer Globalization to the world if we focus on how to improve the living standard of the people. Focusing on the aspects that affect Globalization and solving the problems that arise within it can contribute to a better Globalization. As a student, I can start by thinking of ways that could make us closer to that goal. Here are some things that can be done:

Learning

Studying globalization helped me in understanding the interconnectedness among various countries part of the big circle of trade. Furthermore, studying globalization helped improve my overall understanding of the global markets and how goods and services are being exchanged. It made me notice things that could make or break Globalization for a country.

Globalization is necessary to improve countries' economic condition. And though it has had both positive and negative effects on the entire world, we can hope for more advancement in the global economy as a result of more people studying it.

Reference:

Vanham, P. (n.d.). A brief history of globalization. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/how-globalization-4-0-fits-into-the-history-of-globalization

1 note

·

View note

Text

"the problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other people's money" is such an ironic quote because high income capitalist countries are in fact the one's that heavily rely on resources from all other regions, depleting global resources and driving everyone into ecological collapse.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

To Produce or Not to Produce — Class, Modernity and Identity

Class is a social relationship. Stripped to its base, it is about economics. It’s about being a producer, distributor or an owner of the means and fruits of production. No matter what category any person is, it’s about identity. Who do you identify with? Or better yet, what do you identify with? Every one of us can be put into any number of socio-economic categories. But that isn’t the question. Is your job your identity? Is your economical niche?

Let’s take a step back. What are economics? My dictionary defines it as: “the science of production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.” Fair enough. Economies do exist. In any society where there is unequal access to the necessities of life, where people are dependent upon one another (and more importantly, institutions) there is economy. The goal of revolutionaries and reformists has almost always been about reorganizing the economy. Wealth must be redistributed. Capitalist, communist, socialist, syndicalist, what have you, it’s all about economics. Why? Because production has been naturalized, science can always distinguish economy, and work is just a necessary evil.It’s back to the fall from Eden where Adam was punished to till the soil for disobeying god. It’s the Protestant work ethic and warnings of the sin of ‘idle hands’. Work becomes the basis for humanity. That’s the inherent message of economics. Labor “is the prime basic condition for all human existence, and this to such an extent that, in a sense, we have to say that labor created man himself.” That’s not Adam Smith or God talking (at least this time), that’s Frederick Engels. But something’s very wrong here. What about the Others beyond the walls of Eden? What about the savages who farmers and conquistadors (for all they can be separated) could only see as lazy for not working? Are economics universal?

Let’s look back at our definition.

The crux of economy is production. So if production is not universal, then economy cannot be. We’re in luck, it’s not. The savage Others beyond the walls of Eden, the walls of Babylon, and the gardens: nomadic gatherer/hunters, produced nothing. A hunter does not produce wild animals. A gatherer does not produce wild plants. They simply hunt and gather. Their existence is give and take, but this is ecology, not economy. Every one in a nomadic gatherer/hunter society is capable of getting what they need on their own. That they don’t is a matter of mutual aid and social cohesiveness, not force. If they don’t like their situation, they change it. They are capable of this and encouraged to do so. Their form of exchange is anti-economy: generalized reciprocity. This means simply that people give anything to anyone whenever. There are no records, no tabs, no tax and no running system of measurement or worth. Share with others and they share in return. These societies are intrinsically anti-production, anti-wealth, anti-power, anti-economics. They are simply egalitarian to the core: organic, primal anarchy.

But that doesn’t tell how we became economic people. How work became identity. Looking at the origins of civilization does. Civilization is based off production. The first instance of production is surplus production. Nomadic gatherer/hunters got what they needed when they needed it. They ate animals, insects, and plants. When a number of gatherer/hunters settled, they still hunted animals and gathered plants, but not to eat. At least not immediately.

In Mesopotamia, the cradle of our now global civilization, vast fields of wild grains could be harvested. Grain, unlike meat and most wild plants, can be stored without any intensive technology. It was put in huge granaries. But grain is harvested seasonally. As populations expand, they become dependent upon granaries rather than what is freely available. Enter distribution. The granaries were owned by elites or family elders who were in charge of rationing and distributing to the people who filled their lot. Dependency means compromise: that’s the central element of domestication. Grain must be stored. Granary owners store and ration the grain in exchange for increased social status. Social status means coercive power. This is how the State arose.

In other areas, such as what is now the northwest coast of the United States into Canada, store houses were filled with dried fish rather than grain. Kingdoms and intense chiefdoms were established. The subjects of the arising power were those who filled the storehouses. This should sound familiar. Expansive trade networks were formed and the domestication of plants and then animals followed the expansion of populations. The need for more grain turned gatherers into farmers. The farmers would need more land and wars were waged. Soldiers were conscripted. Slaves were captured. Nomadic gatherer/hunters and horticulturalists were pushed away and killed.

The people did all of this not because the chiefs and kings said so, but because their created gods did. The priest is as important to the emergence of states as chiefs and kings. At some points they were the same position, sometimes not. But they fed off each other. Economics, politics and religion have always been one system. Nowadays science takes the place of religion. That’s why Engels could say that labor is what made humans from apes. Scientifically this is could easily be true. God punished the descendants of Adam and Eve to work the land. Both are just a matter of faith.

But faith comes easily when it comes from the hand that feeds. So long as we are dependent on the economy, we’ll compromise what the plants and animals tells us, what our bodies tell us. No one wants to work, but that’s just the way it is. So we see in the tunnel vision of civilization. The economy needs reformed or revolutionized. The fruit of production needs redistributed.

Enter class struggle.

Class is one of many relationships offered by civilization. It has often been asserted that the history of civilization is the history of class struggle. But I would argue differently. The relationship between the peasant and the king and between chief and commoner cannot be reduced to one set of categories. When we do this, we ignore the differences that accompany various aspects of civilization. Simplification is nice and easy, but if we’re trying to understand how civilization arose so that we can destroy it, we must be willing to understand subtle and significant differences. What could be more significant than how power is created, maintained and asserted? This isn’t done to cheapen the very real resistance that the ‘underclass’ had against elites, far from it. But to say that class or class consciousness are universal ignores important particulars. Class is about capitalism. It’s about a globalizing system based on absolute mediation and specialization. It emerged from feudal relationships through mercantile capitalism into industrial capitalism and now modernity. Proletarian, bourgeoisie, peasant, petite bourgeoisie, these are all social classes about our relationship to production and distribution. Particularly in capitalist society, this is everything. All of this couldn’t have been more apparent than during the major periods of industrialization. You worked in a factory, owned it or sold what came out of it. This was the heyday of class consciousness because there was no question about it. Proletarians were in the same conditions and for the most part they knew that is where they would always be. They spent their days and nights in factories while the ‘high society’ of the bourgeoisie was always close enough to smell, but not taste.

If you believed God, Smith or Engels, labor was your essence. It made you human. To have your labor stolen from you must have been the worst of all crimes. The workers ran the machine and it was within their grasp to take it over. They could get rid of the boss and put in a new one or a worker’s council.

If you believed production was necessary, this was revolutionary. And even more so because it was entirely possible. Some people tried it. Some of them were successful. A lot of them were not. Most revolutions were accused of failing the ideals of those who created them. But in no place did the proletariat resistance end relationships of domination.

The reason is simple: they were barking up the wrong tree. Capitalism is a form of domination, not its source. Production and industrialism are parts of civilization, a heritage much older and far more rooted than capitalism.

But the question is really about identity. The class strugglers accepted their fate as producers, but sought to make the most of a bad situation. That’s a faith that civilization requires. That’s a fate that I won’t accept. That’s a fate the earth won’t accept. The inevitable conclusion of the class struggle is limited because it is rooted in economics. Class is a social relationship, but it is tied to capitalist economics. Proletarians are identified as people who sell their labor. Proletarian revolution is about taking back your labor. But I’m not buying the myths of God, Smith, or Engels. Work and production are not universal and civilization is the problem. What we have to learn is that link between our own class relationships and those of the earlier civilizations is not about who is selling labor and who is buying, but between about the existence of production itself. About how we came to believe that spending our lives building power that is wielded against us is justified. About how compromising our lives as free beings to become workers and soldiers became a compromise we were willing to take.

It is about the material conditions of civilization and the justifications for them, because that is how we will come to understand civilization. So we can understand what the costs of domestication are, for ourselves and the earth. So that we can destroy it once and for all.

This is what the anarcho-primitivist critique of civilization attempts to do. It’s about understanding civilization, how it is created and maintained. Capitalism is a late stage of civilization and class struggle as the resistance to that order is all extremely important to both our understanding of civilization and how to attack it.

There is a rich heritage of resistance against capitalism. It is another part of the history of resistance against power that goes back to its origins. But we should be wary to not take any stage as the only stage. Anti-capitalist approaches are just that, anti-capitalist. It is not anti-civilization. It is concerned with a certain type of economics, not economics, production or industrialism itself. An understanding of capitalism is only useful so far as it is historically and ecologically rooted.

But capitalism has been the major target of the past centuries of resistance. As such, the grasp of class struggle is apparently not easy to move on from. Global capitalism was well rooted by 1500 AD and continued through the technological, industrial and green revolutions of the last 500 years. With a rise in technology it has spread throughout the planet to the point where there is now only one global civilization. But capitalism is still not universal. If we see the world as a stage for class struggle, we are ignoring the many fronts of resistance that are explicitly resisting civilization. This is something that class struggle advocates typically ignore, but in some ways only one of two major problems. The other problem is the denial of modernity.

Modernity is the face of late capitalism. It’s the face that has been primarily spreading over the last 50 years through a series of technological expansions that have made the global economy as we know it now possible. It is identified by hyper-technology and hyper-specialization.

Let’s face it; the capitalists know what they are doing. In the period leading up to World War I and through World War II the threat of proletariat revolution was probably never so strongly felt. Both wars were fought in part to break this revolutionary spirit. But it didn’t end there. In the post war periods the capitalists knew that any kind of major restructuring would have to work against that level of class consciousness. Breaking the ability to organize was central. Our global economy made sense not only in economic terms, but in social terms. The concrete realities of class cohesion were shaken. Most importantly, with global production, a proletarian revolution couldn’t feed and provide for itself. This is one of the primary causes for the ‘failure’ of the socialist revolutions in Russia, China, Nicaragua and Cuba to name just a few.

The structure of modernity is anti-class consciousness. In industrialized nations, most of the work force is service oriented. People could very easily take over any number of stores and Wal-Marts, but where would this get us? The periphery and core of modern capitalism are spread across the world. A revolution would have to be global, but would it look any different in the end? Would it be any more desirable?

In industrializing nations which provide almost everything that the core needs, the reality of class consciousness is very real. But the situation is much the same. We have police and fall in line; they have an everyday reality of military intervention. The threat of state retaliation is much more real and the force of core states to keep those people in line is something most of us probably can’t imagine. But even should revolt be successful, what good are mono-cropped fields and sweatshops? The problem runs much deeper than what can be achieved by restructuring production.

But, in terms of the industrial nations, the problem runs even deeper. The spirit of modernity is extremely individualistic. Even though that alone is destroying everything it means to be human, that’s what we’re up against. It’s like lottery capitalism: we believe that it is possible for each of us to strike it rich. We’re just looking out for number one. We’ll more than happily get rich or die trying. The post-modern ethos that defines our reality tells us that we have no roots. It feeds our passive nihilism that reminds us that we’re fucked, but there’s nothing we can do about it. God, Smith and Engels said so, now movies, music, and markets remind us. The truth is that in this context proletarian identity has little meaning. Classes still exist, but not in any revolutionary context. Study after study shows that most Americans consider them middle class. We judge by what we own rather than what we owe on credit cards. Borrowed and imagined money feeds an identity, a compromise, that we’re willing to sell our souls for more stuff. Our reality runs deeper than proletarian identity can answer. The anti-civilization critique points towards a much more primal source of our condition. It doesn’t accept myths of necessary production or work, but looks to a way of life where these things weren’t just absent, but where they were intentionally pushed away.

It channels something that can be increasingly felt as modernity automates life. As development tears at the remaining ecosystems. As production breeds a completely synthetic life. As life loses meaning. As the earth is being killed.

I advocate primal war.

But this is not an anti-civilization form of class war. It’s not a tool for organizing, but a term for rage. A kind of rage felt at every step of the domestication process. A kind of rage that cannot be put into words. The rage of the primal self subdued by production and coercion. The kind of rage that will not be compromised. The kind of rage that can destroy civilization.

It’s a question of identity.

Are you a producer, distributor, owner, or a human being? Most importantly, do you want to reorganize civilization and its economics or will you settle for nothing less than their complete destruction?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

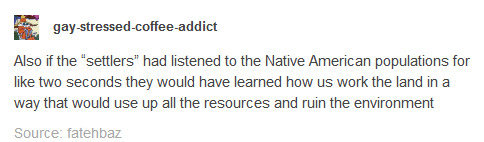

It was done on purpose. They knew.

Ecological degradation is a weapon.

So, this:

Was in response to this:

And I wanted to respond without derailing the original post:

You’re right. But also. What Holleman was kinda trying to do with this research, and what I also believe is true, is that US institutions, corporations, etc., absolutely knew that Indigenous people maintained the best and most time-tested environmental knowledge of North America, but settler-colonial institutions were deliberately choosing to ignore it.

On purpose. Ignoring Indigenous knowledge, purposefully. Ignoring their own settler-colonial reformists and scientists, purposefully. Certain US agencies and institutions, and their proxies or satellites, clearly knew that ecological crisis was coming, and not only did they passively ignore solutions, they actively worked to make ecological crisis worse.

That’s why Holleman says this [in an October 2016 interview]: ”Contemporary Dust Bowl literature […] frames the disaster […] narrowly as a […] natural event, void of social content. […] Prevailing perspectives therefore make invisible the colonial and racial-domination aspects of the [ecological] crisis and lead to the whitewashing of Dust Bowl narratives,“

And from her 2017 article: “By the 1930s there was a well-established body of scholarly literature, government reports, conference proceedings and periodical articles discussing the growing problem of soil erosion across the colonial world. These sources not only provide documentation of the scale of the issue in the absence of consistent data, they also show how this phenomenon was understood by many at the time as linked to white territorial and resource acquisition.”

They knew what they were doing.

What I mean by that is: Another of Holleman’s proposals is that the Dust Bowl was basically a manifestation of the US’s maneuver to, I guess you could say, “outsource its approach to Indigenous people,” by using environmental degradation and ecological crisis as a weapon. A weapon not just against Indigenous people of Turtle Island, but also on a global scale against other regions, and a weapon against its own poor white communities, too. As if the US institutions saw how effectively ecological damage had neutralized many Indigenous communities’ ability to resist, and the US was like “nice, now let’s do it to everybody.”

The time period that Holleman is focusing on is 1870 to 1930-ish, corressponding with the US military campaigns against Indigenous peoples of the 1870s and 1880s, culminating in the “end” of the “war” around 1891 (that’s the date claimed in US settler history books). So after imposing this kind of resource extraction and “removing” Indigenous peoples in “the Wild West” of the 1880s, it’s no coincidence that the US then almost immediately entered “the Gilded Age” and engaged in the Spanish-American War (1898), during which it took control of Cuba, Philippines, etc., effectively outsourcing its industrial agriculture and forcing it on new communities in the tropics and especially in Latin America. And it’s also no coincidence that the end of this period, around World War 2, saw the ascension of the US as global superpower. So the tactics that the US used in that time period, the tactics that created the Dust Bowl, are still used by the US today, on a global scale.

Purposefully ignoring Indigenous environmental knowledge was/is profitable, at least in the short-term. Through monoculture crops, devegetation and timber exctraction, expansive cattle rangeland, etc. Those extraction corporations definitely know that resources are finite. They can cash-in quickly, and bail-out later.

Ignoring Indigenous knowledge of North American landscapes provided, like, some bonus advantages for the settlers, especially during the 1870-1930 time period in discussion. US institutions could (1) make a bunch of money off of industrial-scale resource extraction; (2) they could simultaneously dispossess Indigenous peoples and weaken their communities, thereby eliminating a threat to US cultural hegemony; and (3) when soil degradation and devegetation would ultimately lead to economic collapse even of white settler communities, then unions and working class types living in those regions would also be harmed, thereby neutralizing another threat to US corporate power and allowing further consolidation of US imperial control.

Like feudalism: Hit a rural community with environmental damage. Now they don’t grow food. Next, they’re bankrupt. Debt and bankruptcy anchor people to a single place. Then they’re forced to Participate in the Game and Follow The Rules. They can’t run away from a rental debt; if they try to escape to another side of the country, the banks there still know not to lend to them or give them an account. They’ll get arrested for shoplifting some food. And the result - you could argue, the intended result - is that then people are, essentially, “too poor to get involved in reform, organizing, agitation, and radicalism.”

Holleman, also from the 2017 article: “Globalizing the ecological rift involved the racialized division of nature and labor on a planetary scale as a precondition for the development of the first global agricultural market and food regime. All of this shaped farming practices worldwide, including on the US Southern Plains, as areas were subject to an intensifying ecological imperialism and brought into the global market under conditions of unequal ecological exchange.”

In other words, the 1930s Dust Bowl was a local manifestation of the kind of ecological crisis that Euro-American imperial powers were provoking worldwide - in the African Sahel, in the savanna of Brazil, in the palm plantations of Central America, in the sugar cane fields of Philippines - in order to expand monoculture and industrial-scale resource extraction, and in order to consolidate power, to force people to participate in their “market.”

They did it on purpose.

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

On a planet wrecked and ruined by capital, further debate with left eco-modernism is a distraction. What’s needed more than ever is a deep reflection on political strategy. How can those of us living in the imperial core leverage our position to win an eco-communist future for all? How can we support and amplify existing socialist and anti-imperialist projects and struggles in the periphery? What does a green transition for the core look like in practice if it doesn’t exploit the periphery’s lands, seas, and labour? And what does it mean to fight for a better future on a wounded world? These are the urgent questions of our time. They are questions left eco-modernism has no answer to because it denies the fundamentals of the problem. To move forward together, then, we must forget eco-modernism.

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Class is a social relationship. Stripped to its base, it is about economics. It’s about being a producer, distributor or an owner of the means and fruits of production. No matter what category any person is, it’s about identity.Who do you identify with? Or better yet, what do you identify with? Every one of us can be put into any number of socio-economic categories. But that isn’t the question. Is your job your identity? Is your economical niche?

Let’s take a step back. What are economics? My dictionary defines it as: “the science of production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.” Fair enough. Economies do exist. In any society where there is unequal access to the necessities of life, where people are dependent upon one another (and more importantly, institutions) there is economy.The goal of revolutionaries and reformists has almost always been about reorganizing the economy. Wealth must be redistributed. Capitalist, communist, socialist, syndicalist, what have you, it’s all about economics. Why? Because production has been naturalized, science can always distinguish economy, and work is just a necessary evil.It’s back to the fall from Eden where Adam was punished to till the soil for disobeying god. It’s the Protestant work ethic and warnings of the sin of ‘idle hands’. Work becomes the basis for humanity. That’s the inherent message of economics.Labor “is the prime basic condition for all human existence, and this to such an extent that, in a sense, we have to say that labor created man himself.” That’s not Adam Smith or God talking (at least this time), that’s Frederick Engels.But something’s very wrong here. What about the Others beyond the walls of Eden? What about the savages who farmers and conquistadors (for all they can be separated) could only see as lazy for not working?

Are economics universal?Let’s look back at our definition.The crux of economy is production. So if production is not universal, then economy cannot be. We’re in luck, it’s not. The savage Others beyond the walls of Eden, the walls of Babylon, and the gardens: nomadic gatherer/hunters, produced nothing. A hunter does not produce wild animals. A gatherer does not produce wild plants. They simply hunt and gather. Their existence is give and take, but this is ecology, not economy.Every one in a nomadic gatherer/hunter society is capable of getting what they need on their own. That they don’t is a matter of mutual aid and social cohesiveness, not force. If they don’t like their situation, they change it. They are capable of this and encouraged to do so. Their form of exchange is anti-economy: generalized reciprocity. This means simply that people give anything to anyone whenever. There are no records, no tabs, no tax and no running system of measurement or worth. Share with others and they share in return.These societies are intrinsically anti-production, anti-wealth, anti-power, anti-economics. They are simply egalitarian to the core: organic, primal anarchy.

But that doesn’t tell how we became economic people. How work became identity.Looking at the origins of civilization does.Civilization is based off production. The first instance of production is surplus production. Nomadic gatherer/hunters got what they needed when they needed it. They ate animals, insects, and plants. When a number of gatherer/hunters settled, they still hunted animals and gathered plants, but not to eat.At least not immediately.

In Mesopotamia, the cradle of our now global civilization, vast fields of wild grains could be harvested. Grain, unlike meat and most wild plants, can be stored without any intensive technology. It was put in huge granaries. But grain is harvested seasonally. As populations expand, they become dependent upon granaries rather than what is freely available.Enter distribution. The granaries were owned by elites or family elders who were in charge of rationing and distributing to the people who filled their lot. Dependency means compromise: that’s the central element of domestication. Grain must be stored. Granary owners store and ration the grain in exchange for increased social status. Social status means coercive power. This is how the State arose.

In other areas, such as what is now the northwest coast of the United States into Canada, store houses were filled with dried fish rather than grain. Kingdoms and intense chiefdoms were established. The subjects of the arising power were those who filled the storehouses. This should sound familiar. Expansive trade networks were formed and the domestication of plants and then animals followed the expansion of populations. The need for more grain turned gatherers into farmers. The farmers would need more land and wars were waged. Soldiers were conscripted. Slaves were captured. Nomadic gatherer/hunters and horticulturalists were pushed away and killed.

The people did all of this not because the chiefs and kings said so, but because their created gods did. The priest is as important to the emergence of states as chiefs and kings. At some points they were the same position, sometimes not. But they fed off each other. Economics, politics and religion have always been one system. Nowadays science takes the place of religion. That’s why Engels could say that labor is what made humans from apes. Scientifically this is could easily be true. God punished the descendants of Adam and Eve to work the land. Both are just a matter of faith.

But faith comes easily when it comes from the hand that feeds. So long as we are dependent on the economy, we’ll compromise what the plants and animals tells us, what our bodies tell us. No one wants to work, but that’s just the way it is.So we see in the tunnel vision of civilization. The economy needs reformed or revolutionized. The fruit of production needs redistributed.

Enter class struggle.Class is one of many relationships offered by civilization. It has often been asserted that the history of civilization is the history of class struggle. But I would argue differently. The relationship between the peasant and the king and between chief and commoner cannot be reduced to one set of categories. When we do this, we ignore the differences that accompany various aspects of civilization. Simplification is nice and easy, but if we’re trying to understand how civilization arose so that we can destroy it, we must be willing to understand subtle and significant differences.What could be more significant than how power is created, maintained and asserted? This isn’t done to cheapen the very real resistance that the ‘underclass’ had against elites, far from it. But to say that class or class consciousness are universal ignores important particulars.Class is about capitalism. It’s about a globalizing system based on absolute mediation and specialization. It emerged from feudal relationships through mercantile capitalism into industrial capitalism and now modernity.Proletarian, bourgeoisie, peasant, petite bourgeoisie, these are all social classes about our relationship to production and distribution. Particularly in capitalist society, this is everything. All of this couldn’t have been more apparent than during the major periods of industrialization. You worked in a factory, owned it or sold what came out of it. This was the heyday of class consciousness because there was no question about it. Proletarians were in the same conditions and for the most part they knew that is where they would always be. They spent their days and nights in factories while the ‘high society’ of the bourgeoisie was always close enough to smell, but not taste.

If you believed God, Smith or Engels, labor was your essence. It made you human. To have your labor stolen from you must have been the worst of all crimes. The workers ran the machine and it was within their grasp to take it over. They could get rid of the boss and put in a new one or a worker’s council.

If you believed production was necessary, this was revolutionary. And even more so because it was entirely possible. Some people tried it. Some of them were successful. A lot of them were not. Most revolutions were accused of failing the ideals of those who created them. But in no place did the proletariat resistance end relationships of domination.

The reason is simple: they were barking up the wrong tree. Capitalism is a form of domination, not its source. Production and industrialism are parts of civilization, a heritage much older and far more rooted than capitalism.

But the question is really about identity. The class strugglers accepted their fate as producers, but sought to make the most of a bad situation. That’s a faith that civilization requires. That’s a fate that I won’t accept. That’s a fate the earth won’t accept.The inevitable conclusion of the class struggle is limited because it is rooted in economics. Class is a social relationship, but it is tied to capitalist economics. Proletarians are identified as people who sell their labor. Proletarian revolution is about taking back your labor. But I’m not buying the myths of God, Smith, or Engels. Work and production are not universal and civilization is the problem.What we have to learn is that link between our own class relationships and those of the earlier civilizations is not about who is selling labor and who is buying, but between about the existence of production itself. About how we came to believe that spending our lives building power that is wielded against us is justified. About how compromising our lives as free beings to become workers and soldiers became a compromise we were willing to take.

It is about the material conditions of civilization and the justifications for them, because that is how we will come to understand civilization. So we can understand what the costs of domestication are, for ourselves and the earth. So that we can destroy it once and for all.

This is what the anarcho-primitivist critique of civilization attempts to do. It’s about understanding civilization, how it is created and maintained. Capitalism is a late stage of civilization and class struggle as the resistance to that order is all extremely important to both our understanding of civilization and how to attack it.

There is a rich heritage of resistance against capitalism. It is another part of the history of resistance against power that goes back to its origins. But we should be wary to not take any stage as the only stage. Anti-capitalist approaches are just that, anti-capitalist. It is not anti-civilization. It is concerned with a certain type of economics, not economics, production or industrialism itself. An understanding of capitalism is only useful so far as it is historically and ecologically rooted.

But capitalism has been the major target of the past centuries of resistance. As such, the grasp of class struggle is apparently not easy to move on from. Global capitalism was well rooted by 1500 AD and continued through the technological, industrial and green revolutions of the last 500 years. With a rise in technology it has spread throughout the planet to the point where there is now only one global civilization. But capitalism is still not universal. If we see the world as a stage for class struggle, we are ignoring the many fronts of resistance that are explicitly resisting civilization. This is something that class struggle advocates typically ignore, but in some ways only one of two major problems. The other problem is the denial of modernity.

Modernity is the face of late capitalism. It’s the face that has been primarily spreading over the last 50 years through a series of technological expansions that have made the global economy as we know it now possible. It is identified by hyper-technology and hyper-specialization.

Let’s face it; the capitalists know what they are doing. In the period leading up to World War I and through World War II the threat of proletariat revolution was probably never so strongly felt. Both wars were fought in part to break this revolutionary spirit.But it didn’t end there. In the post war periods the capitalists knew that any kind of major restructuring would have to work against that level of class consciousness. Breaking the ability to organize was central. Our global economy made sense not only in economic terms, but in social terms. The concrete realities of class cohesion were shaken. Most importantly, with global production, a proletarian revolution couldn’t feed and provide for itself. This is one of the primary causes for the ‘failure’ of the socialist revolutions in Russia, China, Nicaragua and Cuba to name just a few.

The structure of modernity is anti-class consciousness. In industrialized nations, most of the work force is service oriented. People could very easily take over any number of stores and Wal-Marts, but where would this get us? The periphery and core of modern capitalism are spread across the world. A revolution would have to be global, but would it look any different in the end? Would it be any more desirable?

In industrializing nations which provide almost everything that the core needs, the reality of class consciousness is very real. But the situation is much the same. We have police and fall in line; they have an everyday reality of military intervention. The threat of state retaliation is much more real and the force of core states to keep those people in line is something most of us probably can’t imagine. But even should revolt be successful, what good are mono-cropped fields and sweatshops? The problem runs much deeper than what can be achieved by restructuring production.

But, in terms of the industrial nations, the problem runs even deeper. The spirit of modernity is extremely individualistic. Even though that alone is destroying everything it means to be human, that’s what we’re up against. It’s like lottery capitalism: we believe that it is possible for each of us to strike it rich. We’re just looking out for number one. We’ll more than happily get rich or die trying.The post-modern ethos that defines our reality tells us that we have no roots. It feeds our passive nihilism that reminds us that we’re fucked, but there’s nothing we can do about it. God, Smith and Engels said so, now movies, music, and markets remind us.The truth is that in this context proletarian identity has little meaning. Classes still exist, but not in any revolutionary context. Study after study shows that most Americans consider them middle class. We judge by what we own rather than what we owe on credit cards. Borrowed and imagined money feeds an identity, a compromise, that we’re willing to sell our souls for more stuff.Our reality runs deeper than proletarian identity can answer. The anti-civilization critique points towards a much more primal source of our condition. It doesn’t accept myths of necessary production or work, but looks to a way of life where these things weren’t just absent, but where they were intentionally pushed away.

It channels something that can be increasingly felt as modernity automates life. As development tears at the remaining ecosystems. As production breeds a completely synthetic life. As life loses meaning. As the earth is being killed.

I advocate primal war. But this is not an anti-civilization form of class war. It’s not a tool for organizing, but a term for rage. A kind of rage felt at every step of the domestication process. A kind of rage that cannot be put into words. The rage of the primal self subdued by production and coercion. The kind of rage that will not be compromised.The kind of rage that can destroy civilization.

It’s a question of identity.Are you a producer, distributor, owner, or a human being?Most importantly, do you want to reorganize civilization and its economics or will you settle for nothing less than their complete destruction?

Kevin Tucker, 2004/2005

From Green Anarchy #18

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/category/topic/green-anarchy-18

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Of all the demographic challenges nations face, ageing is the most serious.

The world is experiencing a seismic demographic shift and no country is immune to the consequences, the inevitable problems that nations face includes overpopulation, sex-ratio imbalances and many more. While increasing life expectancy and declining birth rates are considered major achievements in modern science and healthcare, they will have a significant impact on future generations, ultimately leading to what is commonly known as the ageing population. It is when a country has a high percentage of old generation people, in which it causes a lot of serious problems in human lives, such as the decline in working-age population, increase in health care costs, leading to higher dependency ratio, as well as the changes to the economy, entailing as one of the most paramount demographic challenges the world is facing today.

For instance, sex ratio imbalances is a common feature shown in modern age-sex pyramids as well as being one of the challenges of demography, in which there is an excess of male births for the entire world, a 102 males to 100 females ratio, which is caused by the severe gender inequality - the “son preference”. There are a number of causes for a skewed sex ratio, which can either affect the population sex ratio or the sex ratio at birth. In developing countries, families prefer to have sons, as they are needed to provide a source of income, whereas women are arranged into marriage in exchange for a dowry. Sons become a living pension for their parents, while women are an economical burden. Female infants are often at risk of infanticide, in which it allows the killing of unwanted newborn female babies owing to the preference of males in some societies.

Also, with more advanced technology in the modern world, it allows the identification of the gender of a fetus at an early stage or pregnancy, exacerbating the impact of the son-preference on populations. In particular, China’s one child policy increased the effect of the son-preference on its population, by restricting the number of children to one, it is significantly more important for families to have a son, this caused a greater number of parents to use sex-selection techniques in order to guarantee a son. Typically, the favouring of boys reflects the uneven status of men and women, this can be a product of an antiquated legal system that does not allow women to inherit land or wealth, ultimately leading to gender inequality. With surplus of men in the society, there will be greater mistreatment of women, because women are more desirable, kidnapping, prostitution and trafficking of women increases, as seen in less developed countries such as China and India, in which there will also be increased violence in the society as there is evidence that when single young men congregate, the potential for more organised aggression is likely to increase substantially, resulting in discrimination against women, the neglect of their health care or nutrition, resulting in higher female mortality. Despite the negative consequences, sex ratio imbalances isn’t the greatest challenge nations are facing nowadays, as when there are shortage of women, they are also more valued, resulting in lower rates of depression and suicide, as well as leading to a rise in tolerance towards homosexuality, as there is a surplus of men. Therefore, despite the problems caused by the sex ratio imbalance, it isn’t particurly the greatest challenge nations have to face as it can

be solved with economic development and social change globally, such as in China, the increase in the late 1980s peaked at around 120 males births per 100 female births in 2005 and the imbalance has since decreased due to more economic development, which justifies that with more economic opportunities, the population tend to exhibit lower sex ratio imbalance levels.

On the other hand, human overpopulation is defined as a state in which there are too many people for the health and viability of the environment, which impacts the survival and well being of human populations. To be more specific, it means that there is an overwhelming ecological footprint of a human population of around 7.7 billion, of these 2 billion have been added after 1993, at this rate, human population will reach an atrocious 9.7 billion, damaging the environment faster than it can be repaired by nature, potentially leading to an ecological and societal collapse. Overpopulated areas face many challenges, most of which stem from the impact of climate change or human overexploitation of natural resources, in which Asia is the area at the greatest risk among all other continents.

With a falling mortality rate due to an improved health care system, scientific progress allowed humans to overcome diseases that are previously untreatable, the invention of vaccines and discovery of antibiotics also save millions of lives, which in turn makes it the key factor in unfettered population growth. As the number of annual deaths fall, while births remain constant, the population increases. In certain countries, the impact of migration and accumulation of the population in cities lead to the demographic growth, which ultimately leads to 4 horrendous consequences.

First off, it is the exhaustion of natural resources, in which the main effect of overpopulation is the unequal and unrestrained use of resources, when the consumption rate is faster than the generating rate, it will cause environmental degradation. Consequently, overpopulation will cause fierce rivalries to control resources in developing countries, territorial conflicts over water supply will eventually lead to geopolitical tensions and can result in inevitable wars.

Additionally, with environmental degradation, the unbridled use of natural resources leads to deforestation and desertification, extinction of animals and plant species changes the water cycle and lead to the form of emissions of large quantities of greenhouse gases, and global warming will become more severe.

On the other hand, there will be rising unemployment as there will be a high number of workers fighting over for a limited number of job opportunities and vacancies and seems destined to lead to high rates of unemployment in the future, provoking rising crime and social revolt. All the above will then lead to an increasing living cost in most countries, there will be fewer resources, less water supply and the packing of people into confined spaces and lack of money will decrease the quality of life with poorer sanitation, leading to more widespread diseases and increases the rate of mortality.

Despite overpopulation is said to be the major problem for the human race, this population growth has come with its own advantages and disadvantages depending on the prevailing situation. As the one of the obvious advantages for large population is that there will be greater number of human resources , the abundance of people can lead to fewer workload per person, which may have a positive effect on society.

At the same time, ageing population is also becoming increasingly apparent in many industrialised nations around the globe. Ageing population means that a population structure in which the proportion of people aged 65 or over is high and rising. Not only does it affect developed countries, the proportion of elderly citizens will also grow higher in less developed countries, as they will experience the effects of widespread ageing, including the decline in working-age population, increased health care costs, unsustainable pension commitments and changing demand drivers within the economy. These issues could significantly undermine the high living standard enjoyed in many advanced economies.

As of December 2015, people 65 or older account for more than 20% of the total population in only three countries, Germany, Italy and Japan, however up to this day, the figure has risen to 13 countries and will affect even more countries by 2023, reaching a projected number of 34 countries.