#edward knoblock

Text

John Gielgud was one of the funniest people alive

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

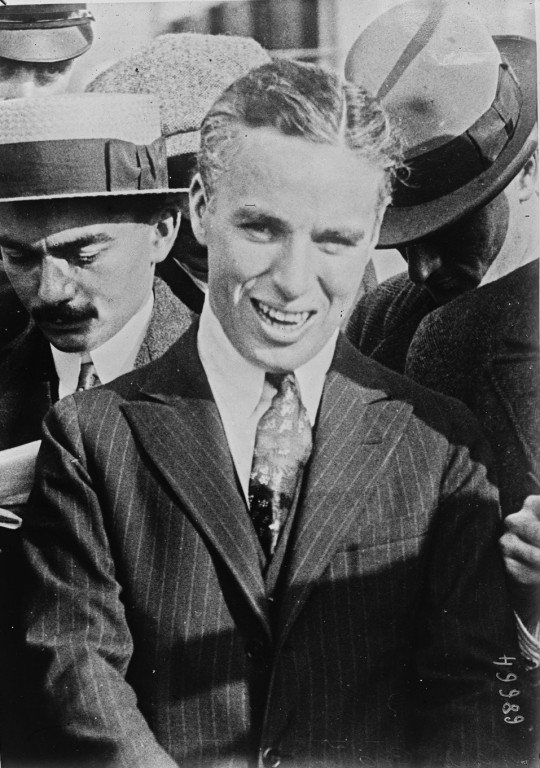

September 9th 1921 - before pulling into Southampton, England (September 10th), the RMS Olympic made a stop to let some passengers off in Cherbourg, France.

Charlie Chaplin got a small taste of the reception that awaited him home in England after a 9 year absence.

An avalanche of reporters speaking both French and English asked him everything from: Why did you come over? Did you bring your make-up? Are you making films over here? to Are you a Bolshevik? What do you think of Lenin? Is it true you are going to be Knighted?

Charlie Chaplin did not speak French despite living in Switzerland for the last 34 years of his life (1953-1977).

As to the question of Knighthood, it would not occur for another 54 years (March 4th 1975)

Photo #2 British playwright Edward Knoblock crossed the Atlantic with him aboard the RMS Olympic.

#charlie chaplin#cherbourg#france#september 9th 1921#also pictured#edward knoblock#british playwright#traveling companion

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Edward Knoblock and Ernst Lubitsch clown around on the set of ‘Rosita’ 1923.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently Watching

KISMET

William Dieterle

USA, 1944

1 note

·

View note

Text

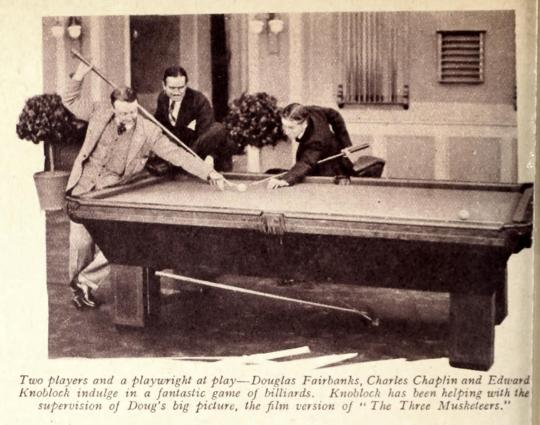

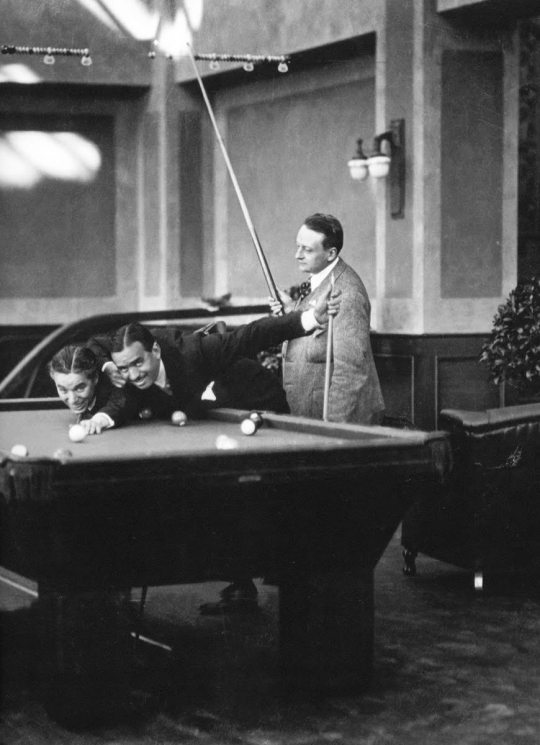

Douglas Fairbanks rehearses for his swashbuckling role as D'Artagnan in Fred Niblo's THE THREE MUSKETEERS in 1921. With him is playwright Edward Knoblock who co-wrote the script.

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gloria Swanson reading The Shulamite by Alice and Claude Askew in this image from the 1921 film UNDER THE LASH. The film is presumed lost. Paramount’s UNDER THE LASH was in fact based on the book The Shulamite. (Well, to be precise, the film is based on the play The Shulamite, by Claude Askew and Edward Knoblock, which in turn was based on the book.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lewis Stone and Helen Hayes in The Sin of Madelon Claudet (Edgar Selwyn, 1931)

Cast: Helen Hayes, Lewis Stone, Neil Hamilton, Cliff Edwards, Jean Hersholt, Marie Prevost, Robert Young, Karen Morley, Charles Winninger, Alan Hale. Screenplay: Charles MacArthur, Ben Hecht, based on a play by Edward Knoblock. Cinematography: Oliver T. Marsh. Art direction: Cedric Gibbons. Film editing: Tom Held. Costume design: Adrian.

If it weren't for her work in movies and on TV, Helen Hayes would probably be consigned to that limbo where celebrated stage actresses of the past like Sarah Siddons or Ellen Terry or Minnie Maddern Fiske reside. But Hayes won two Oscars -- one for this film and the other, 38 years later, for Airport (George Seaton, 1970) -- as well as Emmy, Grammy, and Tony awards, earning the distinction known by the acronym EGOT. The thing is, anyone who knows Hayes's work only from movies and TV may wonder why she is so famous. Neither The Sin of Madelon Claudet nor Airport (in which she plays a cute little old stowaway on a plane) nor her work on such TV series as The Snoop Sisters provides much of a clue as to why she was known as "The First Lady of the American Theater" and has a Broadway playhouse named after her. She spent the peak years of her career, from 1935 to 1956, primarily on stage, with only occasional films and TV appearances during that period. It was probably a wise move: She was already 30 when she followed her husband, Charles MacArthur, to Hollywood and made this film, her first talkie. (She had appeared in only a couple of silent films.) And while it won her the Oscar, and she followed it with a few more significant films, particularly Arrowsmith (John Ford, 1931) and A Farewell to Arms (Frank Borzage, 1932), it soon became clear to her that she was not cut out for film stardom. She was only five feet tall and although pleasant-looking, she was not especially pretty, and in a Hollywood that was looking for the next Greta Garbo or Marlene Dietrich, she was no glamour girl. She would have found herself competing with younger actresses like Bette Davis and Barbara Stanwyck for the plum dramatic parts. So it was back to Broadway and success. Even so, she made her reputation in old-fashioned plays that don't get revived much anymore, like Lawrence Housman's Victoria Regina, Anita Loos's Happy Birthday, and Jean Anouilh's Time Remembered. Although she did play Amanda in a revival of Tennessee Williams's The Glass Menagerie, the revolution in theater that Williams helped bring about took place after she had gone into semi-retirement. As for Madelon Claudet, it's a creaky vehicle at best, based on a play by Edward Knoblock that MacArthur and an uncredited Ben Hecht helped whip into shape after it had been filmed under the title The Lullaby and previewed to a disastrous reception. Hayes had already gone on to work on Arrowsmith, and shooting the new material had to wait until she was through with that film. Even so, Hayes is not particularly convincing as a French farm girl who is left pregnant by a caddish American (Neil Hamilton) and becomes the mistress of a jewel thief posing as an Italian count (Lewis Stone). It's only later, when she goes to jail for ten years as the thief's accomplice, then turns to prostitution to earn the money to put her son (Robert Young), who thinks she's dead, through medical school, that Hayes demonstrates her skill at suffering and pathos.

1 note

·

View note

Text

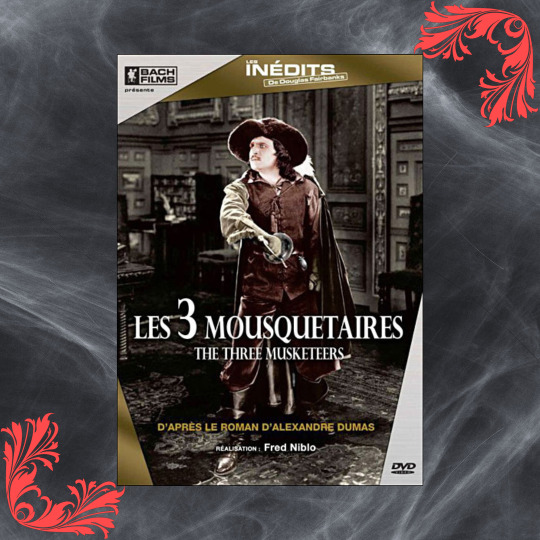

Les Trois Mousquetaires.

1921.

Réalisation : Fred Niblo.

Scénaristes : Douglas Fairbanks, Edward Knoblock et Lotta Woods

Casting :

Douglas Fairbanks, Léon Bary, George Siegmann, Eugene Pallette, Boyd Irwin, Thomas Holding, Sidney Franklin, Charles Stevens, Nigel De Brulier,

Willis Robards, Lon Poff, Mary MacLaren, Marguerite De La Motte, Barbara La Marr, Adolphe Menjou.

Synopsis :

"Un pour tous, tous pour un", s'écrient les mousquetaires. Pour d'Artagnan, Athos, Porthos et Aramis, l'honneur de la reine de France est en danger. En butte aux attaques sournoises du cardinal de Richelieu, la Reine doit son salut au dévouement de ces quatre fidèles mousquetaires.

De Paris à Londres, ils devront affronter la sulfureuse Milady de Winter et Monsieur de Rochefort, âme damné du cardinal.

Plaisir de visionnage : Muet (sonorisé), en Noir et Blanc. Long, plus de 2H.

Pas pour tous les publics.

Richelieu est vil, c'est jouissif.

Note : 3 chats.

Disponibilité : Existe en DVD.

Pas disponible sur les plateforme de streaming à ma connaissance.

Gratuit sur Youtube : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-CRwHGMw6o

Bonus Point Chats : Richelieu a des chatons.

Présents dans des scènes et dans ses bras.

Note : 4 chats.

youtube

0 notes

Audio

Kismet (1953) - Baubles, Bangles, and Beads

Performed by the Ambrosian Chorus and Philharmonia Orchestra, with soloist Valerie Masterson, and John Edwards conducting

Kismet is a 1953 musical adapted by Charles Lederer and Luther Davis from the 1911 play of the same name by Edward Knoblock, The bulk of the music used is adapted from various compositions by 19th-century Russian composer Alexander Borodin, with lyrics and musical arrangements (along with some original music) by Robert Wright and George Forrest. The melody for the above number is taken from the second movement of Borodin’s String Quartet No. 2

#Kismet#Baubles Bangles and Beads#operetta#Borodin#Valerie Masterson#Ambrosian Chorus#Philharmonia Orchestra#John Edwards#music#Charles Lederer#Luther Davis#Edward Knoblock#Alexander Borodin#Robert Wright#George Forrest

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ida Estelle Taylor (May 20, 1894 – April 15, 1958) was an American actress, singer, model, and animal rights activist. With "dark-brown, almost black hair and brown eyes," she was regarded as one of the most beautiful silent film stars of the 1920s.

After her stage debut in 1919, Taylor began appearing in small roles in World and Vitagraph films. She achieved her first notable success with While New York Sleeps (1920), in which she played three different roles, including a "vamp." She was a contract player of Fox Film Corporation and, later, Paramount Pictures, but for the majority of her career she freelanced. She became famous and was commended by critics for her portrayals of historical women in important films: Miriam in The Ten Commandments (1923), Mary, Queen of Scots in Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924), and Lucrezia Borgia in Don Juan (1926).

Although she made a successful transition to sound films, she retired from film acting in 1932 and decided to focus entirely on her singing career. She was also active in animal welfare before her death from cancer in 1958. She was posthumously honored in 1960 with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in the motion pictures category.

Ida Estelle Taylor was born on May 20, 1894 in Wilmington, Delaware. Her father, Harry D. Taylor (born 1871), was born in Harrington, Delaware. Her mother, Ida LaBertha "Bertha" Barrett (November 29, 1874 – August 25, 1965), was born in Easton, Pennsylvania, and later worked as a freelance makeup artist. The Taylors had another daughter, Helen (May 19, 1898 – December 22, 1990), who also became an actress. According to the 1900 census, the family lived in a rented house at 805 Washington Street in Wilmington. In 1903, Ida LaBertha was granted a divorce from Harry on the ground of nonsupport; the following year, she married a cooper named Fred T. Krech.[9] Ida LaBertha's third husband was Harry J. Boylan, a vaudevillian.

Taylor was raised by her maternal grandparents, Charles Christopher Barrett and Ida Lauber Barrett. Charles Barrett ran a piano store in Wilmington, and Taylor studied piano. Her childhood ambition was to become a stage actress, but her grandparents initially disapproved of her theatrical aspirations. When she was ten years old she sang the role of "Buttercup" in a benefit performance of the opera H.M.S. Pinafore in Wilmington. She attended high school but dropped out because she refused to apologize after a troublesome classmate caused her to spill ink from her inkwell on the floor. In 1911, she married bank cashier Kenneth M. Peacock. The couple remained together for five years until Taylor decided to become an actress. She soon found work as an artists' model, posing for Howard Pyle, Harvey Dunn, Leslie Thrasher, and other painters and illustrators.

In April 1918, Taylor moved to New York City to study acting at the Sargent Dramatic School. She worked as a hat model for a wholesale millinery store to earn money for her tuition and living expenses. At Sargent Dramatic School, she wrote and performed one-act plays, studied voice inflection and diction, and was noticed by a singing teacher named Mr. Samoiloff who thought her voice was suitable for opera. Samoiloff gave Taylor singing lessons on a contingent basis and, within several months, recommended her to theatrical manager Henry Wilson Savage for a part in the musical Lady Billy. She auditioned for Savage and he offered her work as an understudy to the actress who had the second role in the musical. At the same time, playwright George V. Hobart offered her a role as a "comedy vamp" in his play Come-On, Charlie, and Taylor, who had no experience in stage musicals, preferred the non-musical role and accepted Hobart's offer.

Taylor made her Broadway stage début in George V. Hobart's Come-On, Charlie, which opened on April 8, 1919 at 48th Street Theatre in New York City. The story was about a shoe clerk who has a dream in which he inherits one million dollars and must make another million within six months. It was not a great success and closed after sixteen weeks. Taylor, the only person in the play who wore red beads, was praised by a New York City critic who wrote, "The only point of interest in the show was the girl with the red beads." During the play's run, producer Adolph Klauber saw Taylor's performance and said to the play's leading actress Aimee Lee Dennis: "You know, I think Miss Taylor should go into motion pictures. That's where her greatest future lies. Her dark eyes would screen excellently." Dennis told Taylor what Klauber said, and Taylor began looking for work in films. With the help of J. Gordon Edwards, she got a small role in the film A Broadway Saint (1919). She was hired by the Vitagraph Company for a role with Corinne Griffith in The Tower of Jewels (1920), and also played William Farnum's leading lady in The Adventurer (1920) for the Fox Film Corporation.

One of Taylor's early successes was in 1920 in Fox's While New York Sleeps with Marc McDermott. Charles Brabin directed the film, and Taylor and McDermott play three sets of characters in different time periods. This film was lost for decades, but has been recently discovered and screened at a film festival in Los Angeles. Her next film for Fox, Blind Wives (1920), was based on Edward Knoblock's play My Lady's Dress and reteamed her with director Brabin and co-star McDermott. William Fox then sent her to Fox Film's Hollywood studios to play a supporting role in a Tom Mix film. Just before she boarded the train for Hollywood, Brabin gave her some advice: "Don't think of supporting Mix in that play. Don't play in program pictures. Never play anything but specials. Mr. Fox is about to put on Monte Cristo. You should play the part of Mercedes. Concentrate on that role and when you get to Los Angeles, see that you play it."

Taylor traveled with her mother, her canary bird, and her bull terrier, Winkle. She was excited about playing Mercedes and reread Alexandre Dumas' The Count of Monte Cristo on the train. When she arrived in Hollywood, she reported to Fox Studios and introduced herself to director Emmett J. Flynn, who gave her a copy of the script, but warned her that he already had another actress in mind for the role. Flynn offered her another part in the film, but she insisted on playing Mercedes and after much conversation was cast in the role. John Gilbert played Edmond Dantès in the film, which was eventually titled Monte Cristo (1922). Taylor later said that she, "saw then that he [Gilbert] had every requisite of a splendid actor." The New York Herald critic wrote, "Miss Taylor was as effective in the revenge section of the film as she was in the first or love part of the screened play. Here is a class of face that can stand a close-up without becoming a mere speechless automaton."

Fox also cast her as Gilda Fontaine, a "vamp", in the 1922 remake of the 1915 Fox production A Fool There Was, the film that made Theda Bara a star. Robert E. Sherwood of Life magazine gave it a mixed review and observed: "Times and movies have changed materially since then [1915]. The vamp gave way to the baby vamp some years back, and the latter has now been superseded by the flapper. It was therefore a questionable move on Mr. Fox's part to produce a revised version of A Fool There Was in this advanced age." She played a Russian princess in the film Bavu (1923), a Universal Pictures production with Wallace Beery as the villain and Forrest Stanley as her leading ma

One of her most memorable roles is that of Miriam, the sister of Moses (portrayed by Theodore Roberts), in the biblical prologue of Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1923), one of the most successful films of the silent era. Her performance in the DeMille film was considered a great acting achievement. Taylor's younger sister, Helen, was hired by Sid Grauman to play Miriam in the Egyptian Theatre's onstage prologue to the film.

Despite being ill with arthritis, she won the supporting role of Mary, Queen of Scots in Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924), starring Mary Pickford. "I've since wondered if my long illness did not, in some measure at least, make for realism in registering the suffering of the unhappy and tormented Scotch queen," she told a reporter in 1926.

She played Lucrezia Borgia in Don Juan (1926), Warner Bros.' first feature-length film with synchronized Vitaphone sound effects and musical soundtrack. The film also starred John Barrymore, Mary Astor and Warner Oland. Variety praised her characterization of Lucrezia: "The complete surprise is the performance of Estelle Taylor as Lucretia [sic] Borgia. Her Lucretia is a fine piece of work. She makes it sardonic in treatment, conveying precisely the woman Lucretia is presumed to have been."

She was to have co-starred in a film with Rudolph Valentino, but he died just before production was to begin. One of her last silent films was New York (1927), featuring Ricardo Cortez and Lois Wilson.

In 1928, she and husband Dempsey starred in a Broadway play titled The Big Fight, loosely based around Dempsey's boxing popularity, which ran for 31 performances at the Majestic Theatre.

She made a successful transition to sound films or "talkies." Her first sound film was the comical sketch Pusher in the Face (1929).

Notable sound films in which she appeared include Street Scene (1931), with Sylvia Sidney; the Academy Award for Best Picture-winning Cimarron (1931), with Richard Dix and Irene Dunne; and Call Her Savage (1932), with Clara Bow.

Taylor returned to films in 1944 with a small part in the Jean Renoir drama The Southerner (released in 1945), playing what journalist Erskine Johnson described as "a bar fly with a roving eye. There's a big brawl and she starts throwing beer bottles." Johnson was delighted with Taylor's reappearance in the film industry: "[Interviewing] Estelle was a pleasant surprise. The lady is as beautiful and as vivacious as ever, with the curves still in the right places." The Southerner was her last film.

Taylor married three times, but never had children. In 1911 at aged 17, she married a bank cashier named Kenneth Malcolm Peacock, the son of a prominent Wilmington businessman. They lived together for five years and then separated so she could pursue her acting career in New York. Taylor later claimed the marriage was annulled. In August 1924, the press mentioned Taylor's engagement to boxer and world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey. In September, Peacock announced he would sue Taylor for divorce on the ground of desertion. He denied he would name Dempsey as co-respondent, saying "If she wants to marry Dempsey, it is all right with me." Taylor was granted a divorce from Peacock on January 9, 1925.

Taylor and Dempsey were married on February 7, 1925 at First Presbyterian Church in San Diego, California. They lived in Los Feliz, Los Angeles. Her marriage to Dempsey ended in divorce in 1931.

Her third husband was theatrical producer Paul Small. Of her last husband and their marriage, she said: "We have been friends and Paul has managed my stage career for five years, so it seemed logical that marriage should work out for us, but I'm afraid I'll have to say that the reason it has not worked out is incompatibility."

In her later years, Taylor devoted her free time to her pets and was known for her work as an animal rights activist. "Whenever the subject of compulsory rabies inoculation or vivisection came up," wrote the United Press, "Miss Taylor was always in the fore to lead the battle against the measure." She was the president and founder of the California Pet Owners' Protective League, an organization that focused on finding homes for pets to prevent them from going to local animal shelters. In 1953, Taylor was appointed to the Los Angeles City Animal Regulation Commission, which she served as vice president.

Taylor died of cancer at her home in Los Angeles on April 15, 1958, at the age of 63. The Los Angeles City Council adjourned that same day "out of respect to her memory." Ex-husband Jack Dempsey said, "I'm very sorry to hear of her death. I didn't know she was that ill. We hadn't seen each other for about 10 years. She was a wonderful person." Her funeral was held on April 17 in Pierce Bros. Hollywood Chapel. She was interred at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, then known as Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery.

She was survived by her mother, Ida "Bertha" Barrett Boylan; her sister, Helen Taylor Clark; and a niece, Frances Iblings. She left an estate of more than $10,000, most of it to her family and $200 for the care and maintenance of her three dogs, which she left to her friend Ella Mae Abrams.

Taylor was known for her dark features and for the sensuality she brought to the films in which she appeared. Journalist Erskine Johnson considered her "the screen's No. 1 oomph girl of the 20s." For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Estelle Taylor was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1620 Vine Street in Hollywood, California.

#estelle taylor#silent era#silent hollywood#silent movie stars#golden age of hollywood#classic movie stars#1920s hollywood#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

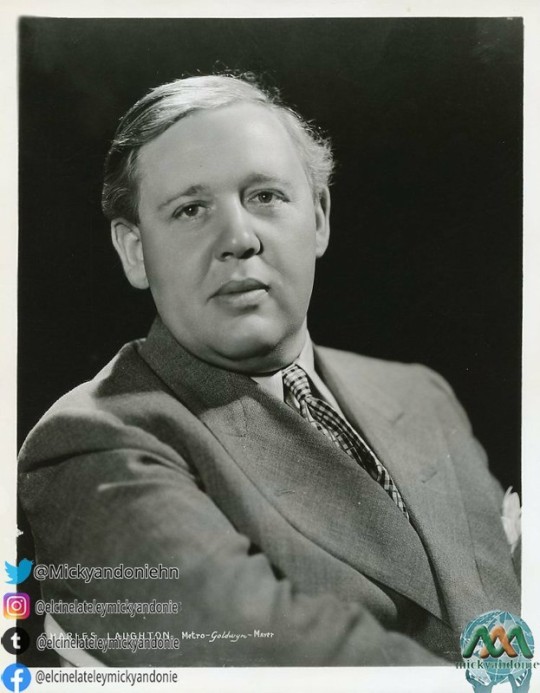

Charles Laughton.

Filmografía

Películas

- Bluebottles, The Tonic, Daydreams (1928) Dir.: Ivor Montagu

- Piccadilly (1929) Dir.: Ewald Andrea Dupont.

- Wolves (1930).

- Down River (1931) Dir. Peter Godfrey

-El caserón de las sombras (The Old Dark - House, 1932) Dir. James Whale

- Entre la espada y la pared (The Devil and the Deep, 1932) Dir. Marion Gering

- Justicia divina/El asesino de Mr. Medland (Payment Deferred, 1932) Dir. Lothar Mendes

- El signo de la cruz (The Sign of the Cross, 1932) Dir. Cecil B. De Mille

- Si yo tuviera un millón (If I Had a Million, 1932) Dirs. Ernst Lubitsch, Norman Taurog, Stephen Roberts, Norman McLeod, James Cruse, William A. - Seiter y H. Bruce Humberstone

- La isla de las almas perdidas (Island of Lost Souls, 1932) Dir. Erle C. Kenton

- La vida privada de Enrique VIII (The Private Life of Henry VIII, 1933) Dir. Alexander Korda

- White Woman (1933) Dir. Stuart Walker

- The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934) Dir. Sidney Franklin

- Nobleza obliga (Ruggles of Red Gap, 1935) Dir. Leo McCarey

- Los miserables (Les Misérables, 1935) Dir. Richard Boleslawsky

- Rebelión a bordo (Mutiny on the Bounty, 1935) Dir. Frank Lloyd

- Rembrandt (Rembrandt, 1936) Dir. Alexander Korda

- Yo, Claudio (I, Claudius, 1937) Dir. Joseph von Sternberg.

- Bandera amarilla (Vessel of Wrath, 1938) Dir. Eric Pommer (Laughton es actor y coproductor de esta película).

- Las calles de Londres (St. Martin's Lane, 1938) Dir. Tim Whelan (Laughton es actor y coproductor de esta película).

- La posada de Jamaica (Jamaica Inn, 1939) Dir. Alfred Hitchcock (Laughton es actor y coproductor de esta película).

- Esmeralda, la zíngara (The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1939) Dir. William Dieterle

- Laughton en la película Ellos sabían lo que querían (1940), con Carole Lombard y Frank Fay.

- They Knew What They Wanted (1940) Dir. Garson Kanin

- Casi un ángel (It Started with Eve, 1941) Dir. Henry Koster

- Se acabó la gasolina (The Tuttles of Tahiti, 1942) Dir. Charles Vidor

- Seis destinos (Tales of Manhattan, 1942) Dir. Julien Duvivier

- Stand by for Action (1943) Dir. Robert Z. Leonard

- Forever and a Day (1943) Dirs. René Clair, Edmund Goulding, Cedric Hardwicke, Frank Lloyd, Victor Saville.

-Esta tierra es mía (This Land Is Mine, 1943) Dir. Jean Renoir

- The Man from Down Under (1943) Dir. Robert Z. Leonard

- The Canterville Ghost (1944) Dir. Jules Dassin

- El sospechoso (The Suspect, 1944) Dir. Robert Siodmak

- El capitán Kidd (Captain Kidd, 1945) Dir. Rowland V. Lee

- Su primera noche (Because of Him, 1946) Dir. Richard Wallace

- Arco de triunfo (Arch of Triumph, 1947) Dir. Lewis Milestone

- El reloj asesino (The Big Clock, 1947) Dir. John Farrow

- El proceso Paradine (The Paradine Case, 1948) Dir. Alfred Hitchcock

- On our Merry way/A Miracle can Happen (1948) Dirs. King Vidor, Leslie Fenton, John Huston, George Stevens.

- The Girl from Manhattan (1948) Alfred E. Green

- Soborno (The Bribe, 1949) Dir. Robert Z. Leonard

- El hombre de la torre Eiffel (The Man on the Eiffel Tower, 1949) Dir. Burgess Meredith (codirectores no acreditados: Charles Laughton y Franchot Tone).

- No estoy sola (The Blue Veil, 1951) Dir. Curtis Bernhardt

- The Strange Door (1951) Dir. Joseph Pevney

- Cuatro páginas de la vida (O. Henry's Full House, 1952) Dir. Henry Koster

- Abbott and Costello Meet Captain Kidd (1952) Dir. Charles Lamont

- Salomé (Salome, 1953) Dir. William Dieterle

- La reina virgen (Young Bess, 1953) Dir. George Sidney

- El déspota (Hobson's Choice, 1954) Dir. David Lean

- La noche del cazador (The Night of the Hunter, 1954) Dir. Charles Laughton (no aparece como actor en la película).

T- estigo de cargo (Witness for the Prosecution, 1957) Dir. Billy Wilder

- Bajo diez banderas (Sotto dieci bandiere, 1960) Dir. Diulio Colletti

Espartaco (Spartacus, 1960) Dir, Stanley Kubrick

- Tempestad sobre Washington (Advise and Consent, 1962) Dir. Otto Preminger.

Documentales

- The Epic That Never Was (1965). Dirigido por Bill Duncalf y presentado por Dirk Bogarde. Documental de la BBC sobre el rodaje de I, Claudius con diversas escenas acabadas. (VHS, DVD).

- Callow's Laughton (1987). Documental de la Yorkshire TV-ITV dirigido por Nick Gray y presentado por Simon Callow sobre Charles Laughton.

- Charles Laughton Directs The Night of the Hunter (2002). Documental dirigido por Robert Gitt a partir de tomas descartadas de la Película.

Teatro

Debut teatral (1913). Stonyhurst College, Reino Unido

- The Private Secretary per Charles Hawtrey

Teatro amateur (hasta 1925). Scarborough, Reino Unido

- The Dear Departed por Stanley Houghton

- Trelawney of The Wells por Arthur Wing Pinero

- Hobson's Choice por Harold Brighouse

1926

- The Government Inspector. por Nicolai Gogol. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- Los puntales de la sociedad por Henrik Ibsen. Dir. Sybil Arundale

- El jardín de los cerezos por Antón Chéjov. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- Las tres hermanas por Antón Chéjov. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- Liliom por Ferencz Molnar. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

1927

- The Greater Love por James B. Fagan. Dir. James B. Fagan y Lewis Casson

- Angela por Lady Bell. Dir. Lewis Casson

Vestire gli ignudi por Luigi Pirandello. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- Medea por Eurípides. Dir. Lewis Casson

- The Happy Husband por Harrison Owen. Dir. Basil Dean

- Paul Y por Dimitri Merejovski. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- Mr. Prohack por Arnold Bennet y Edward Knoblock. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

1928

- A Man with Red Hair por Benn W. Levy, a partir de la novela de Hugh Walpole. Dir. Theodore Komisarjevsky

- The Making of an Immortal por George Moore. Dir. Robert Atkins

- Riverside Nights por Nigel Playfair y A.P. Herbert. Dir. Nigel Playfair

- Alibi per Michael Morton, a partir de la novela de Agatha Christie. Dir. Gerald duMaurier

- Mr. Pickwick por Cosmo Hamilton y Frank C. Reilly, a partir de la novela de Charles Dickens. Dir. Basil Dean

1929

- Beauty por Jacques Deval (adapt. inglesa: Michael Morton). Dir. Felix Edwardes

- The Silver Tassie por Sean O'Casey. Dir. Raymond Massey

1930

- French Leave por Reginald Berkeley. Dir. Eille Norwood

- On the Spot por Edgar Wallace. Dir. Edgar Wallace

1930

- Payment Deferred por Jeffrey Dell, a partir de la novela de C.S. Forrester. Dir. H.K. Ailiff

1931

-Gira americana (Chicago y Nueva York) de Payment Deferred y Alibi (esta última retítulada The Fatal Alibi y dirigida por Jed Harris).

Old Vic: temporada 1933-34. Londres. Reino Unido. Todas las obras dirigidas por Tyrone Guthrie.

El jardín de los cerezos por Antón Chéjov. Dir. Charles Laughton

1951-52 Estados Unidos y Reino Unido (Gira).

Don Juan in Hell de Man and Superman por George Bernard Shaw. Dir. Charles Laughton.

1953 Estados Unidos (Gira).

John Brown's Body por Stephen Vincent Benet. Dir. y Adaptación: Charles Laughton (no apareció como actor).

1954 Estados Unidos (Gira).

The Caine Mutiny Court Martial por Herman Wouk, a partir de su novela. Dir. Charles Laughton (no apareció como actor).

1956 Nueva York, Estados Unidos.

Major Barbara por George Bernard Shaw. Dir. Charles Laughton

1956 Londres, Reino Unido

The Party por Jane Arden. Dir. Charles Laughton

1959 Stratford-upon-Avon, Reino Unido

El sueño de una noche de verano por William Shakespeare. Dir. Peter Hall

El rey Lear por William Shakespeare. Dir. Glen Byam Shaw.

Créditos: Tomado de Wikipedia

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Laughton

#HONDURASQUEDATEENCASA

#ELCINELATELEYMICKYANDONIE

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931)

Western theatrical plays, so often the province of or commissioned by wealthy patrons, became more accessible to commoners in the nineteenth century. As the concept of leisure became increasingly widespread, the subject material in the contemporary stage plays reflected the values of those times, namely the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Those reflections resulted in the melodrama being the leading theater genre at that time – those melodramas were works of clear (at times ham-fisted) moral distinctions, often featuring a female lead embodying the piece’s major themes, and usually ending in some conclusion where the lead character would receive their dues depending on their actions. Melodrama’s popularity onstage, showing signs of waning at the turn of the twentieth century, soon transferred to film.

The silent era and early days of synchronized sound in cinema contained numerous examples of melodrama – such as Orphans of the Storm (1922); both adaptations of Stella Dallas (1925 and 1937); and Now, Voyager (1942) – and launched the careers of some of Hollywood’s best actresses of this era. A longtime stage fixture, becoming a staple of American cinema, also resulted in more stage actors dipping their toes into the movies. That brings us to The Sin of Madelon Claudet, directed by Edgar Selwyn, released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), and starring the “First Lady of American Theatre”, Helen Hayes. Hayes had appeared in silent films, and The Sin of Madelon Claudet was set to be her talkie debut – a fact that gave Hayes some trepidation, as numerous silent film actors’ careers were destroyed with the advent of talkies.

The Sin of Madelon Claudet begins at its chronological end. A woman named Alice (Karen Morley) is tired of her husband’s (Robert Young) neglect, and intimates her frustration to her friend, the elderly Dr. Dulac (Jean Hersholt). Dr. Dulac, listening to Alice’s story, advises against her plans by telling her the story of Madelon Claudet. Madelon (Hayes) has a son with an American painter named Larry Maynard (Neil Hamilton). Larry had told Madelon that he needed to leave France because of his ailing father; when Madelon herself makes the trans-Atlantic voyage, she learns that Larry departed France to marry someone else. Madelon’s father (Russ Powell) attempts to set her up with a farmer (Alan Hale), but she refuses when they stipulate that she must abandon her newborn, illegitimate son. They abandon Madelon and her son, and she will have numerous tribulations: being convicted of a violent robbery she took no part in, ten years of imprisonment, and a heartbreaking decision regarding her son’s future.

As Madelon, Hayes transitions from a naïve and primaveral young adult to Parisian socialite to a raddled streetwalker whose lifetime of suffering can be seen by just looking at her face. One transformation is already a demanding task for any actor, but two within a film’s 90-minute runtime? That sounds like a recipe for pacing problems, which can make the transitions into those transformations unbelievable. But Hayes – taking this material from Edward Knoblock’s play Lullaby and adapted for film by screenwriters Charles MacArthur (1939’s Wuthering Heights and 1940’s His Girl Friday) and Ben Hecht (uncredited; 1932’s Scarface and 1945’s Spellbound) – is outstanding. Her performance allows the audience to believe the radical changes in Madelon’s behavior and personality, adjusting to the times and unenviable situations she finds herself in. For a melodrama, many actors might oversell themselves, like a rushing string line piercing its way through a dramatic, but quiet scene. But Hayes’ performance is grounded, triumphing over the narrative developments now easily dismissed as cliched. Her Madelon Claudet is a resilient person, though this is not obvious on any first impression.

The film shares with Stella Dallas how deeply selfless motherly love may go (an aspect of melodrama that has lasted through the decades); yet, The Sin of Madelon Claudet is a movie assertive in its depiction of sexuality. Madelon is certainly a character that could only have been depicted in a classic Hollywood movie during the pre-Code era (referring to the Hays Code – a set of censorship guidelines that the major American movie studios did not truly enforce until 1934 and were replaced in 1968 with the current MPAA ratings system in the United States). From depicting an illegitimate child to pre-marital cohabitation to a suggestion of prostitution, The Sin of Madelon Claudet does not depict its eponymous character as any less of a person because of those choices, among other aspects of her life that might be considered, “immoral”. One wonders what the titular “sin” is. Is it Madelon’s fateful decision regarding her child? Certainly not; Madelon weighs what might happen to her son if she acts upon what she wants more than anything and decides against it in the interests of letting him live a complete, untroubled life. Madelon is overly enraptured in her desire for romance, but never does this appear to be sinful. Perhaps this can be attributed to producer Irving Thalberg’s unilateral decision to rename The Sin of Madelon Claudet from Lullaby (the original title of Knoblock’s play). Thalberg deemed the initial title juvenile; audiences seek hedonism, lust, sex, and all sorts of unmentionable things, Thalberg probably reasoned, and so “sin” was added without much regard to Madelon’s conduct.

The work of Edgar Selwyn and Oliver T. Marsh reveal a neophyte director (Selwyn was better known as a playwright, not a director) adhering too strictly to a conventional cinematic playbook and a cinematographer who seems to have not altered has techniques since the early 1920s. Too often The Sin of Madelon Claudet resembles a stilted silent film – through its direction, cinematography, and performances from anyone not named Helen Hayes or Jean Hersholt. This is not to bash on the aesthetic of silent films and how critical they were to the development of filmmaking’s visual grammar, but how much The Sin of Madelon Claudet resembles, visually, like a sizable handful of deadening silent films that are not concise in their compositions and edits. Thankfully, The Sin of Madelon Claudet moves quickly, but never at the expense of the viewer’s comprehension and the necessary time it takes to reflect on an individual or series of scenes.

One wonders what The Sin of Madelon Claudet might be like without Helen Hayes as Madelon. This is a star vehicle for Hayes, a film that could have secured a lengthy screen career for the theater stalwart. The film might collapse without her commanding performance, given the lack of quality crewmembers behind the camera. But for Hayes, the theater remained first in her artistic soul. She would continue to appear in stage productions until the 1970s, with the occasional supporting role in a film attracting her interest. Hayes would close out her career with a succession of television movies in the 1980s.

The Sin of Madelon Claudet solidified the popularity of the melodrama – especially melodramas that had anything to do with a woman, mothers and otherwise, sacrificing their opportunities for happiness when considering the potentially life-destroying consequences that decision might entail – for the next few decades in Hollywood. Most notably, the likes of Barbara Stanwyck (in Stella Dallas) and Bette Davis (in 1934’s Of Human Bondage) became household names after appearing in melodramas – Davis exceled in melodramas, and would be my first choice for a melodrama if anyone handed over a blank check to me to cast such a film. Please do not read that last sentence as a suggestion. But as the major Hollywood movie studios began settling into producing films with synchronized sound, there was a stage actor – Hayes – who brought to talkies a tradition first popularized by her specialty, the theater. Such is and was the relationship between theater and cinema, perhaps to a lesser extent today. The younger artform adopted certain conventions from the older one, and both adapted to cultural and technological changes borne from disruptive times.

My rating: 7.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#The Sin of Madelon Claudet#Edgar Selwyn#Helen Hayes#Lewis Stone#Jean Hersholt#Marie Prevost#Robert Young#Charles MacArthur#Ben Hecht#Irving Thalberg#Oliver T. Marsh#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

1 note

·

View note

Text

Taking in a game of pool. Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks and British Playwright Edward Knoblock, circa 1922.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ida Estelle Taylor (May 20, 1894 – April 15, 1958) was an American actress, singer, model, and animal rights activist. With "dark-brown, almost black hair and brown eyes," she was regarded as one of the most beautiful silent film stars of the 1920s.

After her stage debut in 1919, Taylor began appearing in small roles in World and Vitagraph films. She achieved her first notable success with While New York Sleeps (1920), in which she played three different roles, including a "vamp." She was a contract player of Fox Film Corporation and, later, Paramount Pictures, but for the most part of her career she freelanced. She became famous and was commended by critics for her portrayals of historical women in important films: Miriam in The Ten Commandments (1923), Mary, Queen of Scots in Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924), and Lucrezia Borgia in Don Juan (1926).

Although she made a successful transition to sound films, she retired from film acting in 1932 and decided to focus entirely on her singing career. She was also active in animal welfare before her death from cancer in 1958. She was posthumously honored in 1960 with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in the motion pictures category.

Ida Estelle Taylor was born on May 20, 1894 in Wilmington, Delaware. Her father, Harry D. Taylor (born 1871), was born in Harrington, Delaware.[8] Her mother, Ida LaBertha "Bertha" Barrett (November 29, 1874 – August 25, 1965), was born in Easton, Pennsylvania, and later worked as a freelance makeup artist. The Taylors had another daughter, Helen (May 19, 1898 – December 22, 1990), who also became an actress. According to the 1900 census, the family lived in a rented house at 805 Washington Street in Wilmington In 1903, Ida LaBertha was granted a divorce from Harry on the ground of nonsupport; the following year, she married a cooper named Fred T. Krech. Ida LaBertha's third husband was Harry J. Boylan, a vaudevillian.

Taylor was raised by her maternal grandparents, Charles Christopher Barrett and Ida Lauber Barrett. Charles Barrett ran a piano store in Wilmington, and Taylor studied piano. Her childhood ambition was to become a stage actress, but her grandparents initially disapproved of her theatrical aspirations. When she was ten years old she sang the role of "Buttercup" in a benefit performance of the opera H.M.S. Pinafore in Wilmington. She attended high school[6] but dropped out because she refused to apologize after a troublesome classmate caused her to spill ink from her inkwell on the floor. In 1911, she married bank cashier Kenneth M. Peacock. The couple remained together for five years until Taylor decided to become an actress. She soon found work as an artists' model, posing for Howard Pyle, Harvey Dunn, Leslie Thrasher, and other painters and illustrators.

In April 1918, Taylor moved to New York City to study acting at the Sargent Dramatic School. She worked as a hat model for a wholesale millinery store to earn money for her tuition and living expenses. At Sargent Dramatic School, she wrote and performed one-act plays, studied voice inflection and diction, and was noticed by a singing teacher named Mr. Samoiloff who thought her voice was suitable for opera. Samoiloff gave Taylor singing lessons on a contingent basis and, within several months, recommended her to theatrical manager Henry Wilson Savage for a part in the musical Lady Billy. She auditioned for Savage and he offered her work as an understudy to the actress who had the second role in the musical. At the same time, playwright George V. Hobart offered her a role as a "comedy vamp" in his play Come-On, Charlie, and Taylor, who had no experience in stage musicals, preferred the non-musical role and accepted Hobart's offer.

Taylor made her Broadway stage début in George V. Hobart's Come-On, Charlie, which opened on April 8, 1919 at 48th Street Theatre in New York City. The story was about a shoe clerk who has a dream in which he inherits one million dollars and must make another million within six months. It was not a great success and closed after sixteen weeks. Taylor, the only person in the play who wore red beads, was praised by a New York City critic who wrote, "The only point of interest in the show was the girl with the red beads." During the play's run, producer Adolph Klauber saw Taylor's performance and said to the play's leading actress Aimee Lee Dennis: "You know, I think Miss Taylor should go into motion pictures. That's where her greatest future lies. Her dark eyes would screen excellently." Dennis told Taylor what Klauber said, and Taylor began looking for work in films. With the help of J. Gordon Edwards, she got a small role in the film A Broadway Saint (1919).nShe was hired by the Vitagraph Company for a role with Corinne Griffith in The Tower of Jewels (1920), and also played William Farnum's leading lady in The Adventurer (1920) for the Fox Film Corporation.

One of Taylor's early successes was in 1920 in Fox's While New York Sleeps with Marc McDermott. Charles Brabin directed the film, and Taylor and McDermott play three sets of characters in different time periods. This film was lost for decades, but has been recently discovered and screened at a film festival in Los Angeles. Her next film for Fox, Blind Wives (1920), was based on Edward Knoblock's play My Lady's Dress and reteamed her with director Brabin and co-star McDermott. William Fox then sent her to Fox Film's Hollywood studios to play a supporting role in a Tom Mix film. Just before she boarded the train for Hollywood, Brabin gave her some advice: "Don't think of supporting Mix in that play. Don't play in program pictures. Never play anything but specials. Mr. Fox is about to put on Monte Cristo. You should play the part of Mercedes. Concentrate on that role and when you get to Los Angeles, see that you play it."

Taylor traveled with her mother, her canary bird, and her bull terrier, Winkle. She was excited about playing Mercedes and reread Alexandre Dumas' The Count of Monte Cristo on the train. When she arrived in Hollywood, she reported to the Fox studios and introduced herself to director Emmett J. Flynn, who gave her a copy of the script but warned her that he already had another actress in mind for the role. Flynn offered her another part in the film, but she insisted on playing Mercedes and after much conversation was cast in the role. John Gilbert played Edmond Dantès in the film, which was eventually titled Monte Cristo (1922). Taylor later said that she "saw then that he [Gilbert] had every requisite of a splendid actor." The New York Herald critic wrote "Miss Taylor was as effective in the revenge section of the film as she was in the first or love part of the screened play. Here is a class of face that can stand a close-up without becoming a mere speechless automaton."

Fox also cast her as Gilda Fontaine, a "vamp", in the 1922 remake of the 1915 Fox production A Fool There Was, the film that made Theda Bara a star. Robert E. Sherwood of Life magazine gave it a mixed review and observed: "Times and movies have changed materially since then [1915]. The vamp gave way to the baby vamp some years back, and the latter has now been superseded by the flapper. It was therefore a questionable move on Mr. Fox's part to produce a revised version of A Fool There Was in this advanced age." She played a Russian princess in the film Bavu (1923), a Universal Pictures production with Wallace Beery as the villain and Forrest Stanley as her leading man.

One of her most memorable roles is that of Miriam, the sister of Moses (portrayed by Theodore Roberts), in the biblical prologue of Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1923), one of the most successful films of the silent era. Her performance in the DeMille film was considered a great acting achievement. Taylor's younger sister, Helen, was hired by Sid Grauman to play Miriam in the Egyptian Theatre's onstage prologue to the film.

Despite being ill with arthritis, she won the supporting role of Mary, Queen of Scots in Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall (1924), starring Mary Pickford. "I've since wondered if my long illness did not, in some measure at least, make for realism in registering the suffering of the unhappy and tormented Scotch queen," she told a reporter in 1926.

She played Lucrezia Borgia in Don Juan (1926), Warner Bros.' first feature-length film with synchronized Vitaphone sound effects and musical soundtrack. The film also starred John Barrymore, Mary Astor and Warner Oland. Variety praised her characterization of Lucrezia: "The complete surprise is the performance of Estelle Taylor as Lucretia [sic] Borgia. Her Lucretia is a fine piece of work. She makes it sardonic in treatment, conveying precisely the woman Lucretia is presumed to have been."

She was to have co-starred in a film with Rudolph Valentino, but he died just before production was to begin. One of her last silent films was New York (1927), featuring Ricardo Cortez and Lois Wilson.

In 1928, she and husband Dempsey starred in a Broadway play titled The Big Fight, loosely based around Dempsey's boxing popularity, which ran for 31 performances at the Majestic Theatre.

She made a successful transition to sound films or "talkies." Her first sound film was the comical sketch Pusher in the Face (1929).

Notable sound films in which she appeared include Street Scene (1931), with Sylvia Sidney; the Academy Award for Best Picture-winning Cimarron (1931), with Richard Dix and Irene Dunne; and Call Her Savage (1932), with Clara Bow.

Taylor returned to films in 1944 with a small part in the Jean Renoir drama The Southerner (released in 1945), playing what journalist Erskine Johnson described as "a bar fly with a roving eye. There's a big brawl and she starts throwing beer bottles." Johnson was delighted with Taylor's reappearance in the film industry: "[Interviewing] Estelle was a pleasant surprise. The lady is as beautiful and as vivacious as ever, with the curves still in the right places." The Southerner was her last film.

Taylor married three times, but never had children. In 1911 at aged 17, she married a bank cashier named Kenneth Malcolm Peacock, the son of a prominent Wilmington businessman. They lived together for five years and then separated so she could pursue her acting career in New York. Taylor later claimed the marriage was annulled. In August 1924, the press mentioned Taylor's engagement to boxer and world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey.[36] In September, Peacock announced he would sue Taylor for divorce on the ground of desertion. He denied he would name Dempsey as co-respondent, saying "If she wants to marry Dempsey, it is all right with me." Taylor was granted a divorce from Peacock on January 9, 1925.

Taylor and Dempsey were married on February 7, 1925 at First Presbyterian Church in San Diego, California. They lived in Los Feliz, Los Angeles. Her marriage to Dempsey ended in divorce in 1931.

Her third husband was theatrical producer Paul Small. Of her last husband and their marriage, she said: "We have been friends and Paul has managed my stage career for five years, so it seemed logical that marriage should work out for us, but I'm afraid I'll have to say that the reason it has not worked out is incompatibility."

In her later years, Taylor devoted her free time to her pets and was known for her work as an animal rights activist. "Whenever the subject of compulsory rabies inoculation or vivisection came up," wrote the United Press, "Miss Taylor was always in the fore to lead the battle against the measure." She was the president and founder of the California Pet Owners' Protective League, an organization that focused on finding homes for pets to prevent them from going to local animal shelters. In 1953, Taylor was appointed to the Los Angeles City Animal Regulation Commission, which she served as vice president.

Taylor died of cancer at her home in Los Angeles on April 15, 1958, at the age of 63. The Los Angeles City Council adjourned that same day "out of respect to her memory." Ex-husband Jack Dempsey said, "I'm very sorry to hear of her death. I didn't know she was that ill. We hadn't seen each other for about 10 years. She was a wonderful person." Her funeral was held on April 17 in Pierce Bros. Hollywood Chapel. She was interred at Hollywood Forever Cemetery, then known as Hollywood Memorial Park Cemetery.

She was survived by her mother, Ida "Bertha" Barrett Boylan; her sister, Helen Taylor Clark; and a niece, Frances Iblings. She left an estate of more than $10,000, most of it to her family and $200 for the care and maintenance of her three dogs, which she left to friend Ella Mae Abrams.

Taylor was known for her dark features and for the sensuality she brought to the films in which she appeared. Journalist Erskine Johnson considered her "the screen's No. 1 oomph girl of the 20s." For her contribution to the motion picture industry, Estelle Taylor was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1620 Vine Street in Hollywood, California.

#estelle taylor#classic hollywood#golden age of hollywood#classic movie stars#classic cinema#old hollywood#classic movies#silent era#silent stars#silent cinema

0 notes

Photo

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and family and family with Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and playwright, Edward Knoblock, 1923

#Sir Arthur Conan Doyle#mary pickford#douglas fairbanks#edward knoblock#silent film#silent era#1920s#classic film#classic actress#classic actor#vintage#20s#my scans

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moonlight Sonata

Movie review: Moonlight Sonata by #LotharMendes starring #IgnacyPaderewski

BB.5

(out of 5)

Real-life pianist Ignacy Paderewski begins this film with half an hour of footage of his performing popular classical pieces in concert, showing as much prowess at the age of 77 on the keyboard as he later shows in his role. The concert scene is followed by a brief interview in which Paderewski reflects on his life and career, all of which would make for a satisfying short before…

View On WordPress

#Barbara Greene#Binkie Stuart#Charles Farrell#E.M. Delafield#Edward Knoblock#Eric Portman#Hans Rameau#Ignacy Jan Paderewski#Jan Stallich#Laurence Hanray#Lothar Mendes#Marie Tempest#Queenie Leonard#W. Graham Brown

0 notes