#eiji ogata

Text

the lil shit of the older gen

#i need to draw more of older gen#non ask#kaiju no. 8#kn8#kn8 fanart#kn8 manga spoilers#eiji hasegawa#jugo ogata#badlydrawnjakdf

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Kaiju no. 8#naoya matsumoto#kn8#monster no. 8#icons#twitter icons#manga icons#gen narumi#eiji hasegawa#jugo ogata#jura igarashi#hakua igarashi#keiji itami#bakko#takamichi hodaka#kn9#kaiju no. 9#kanji nagamine#official media#official art#manga art#kn8 icons#kn8spoilers

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ultraman, Japan's symbol of hope

We cant have Ultraman without first having Eiji Tsuburaya, founder of Tsuburaya productions, the producer of most all Ultraman shows since the original one back in 1966. Even as a kid, Eiji was considered as a prodigy, known in his town for his craftsmanship of wooden toys, though growing up, a young Eiji would eventually come across a copy of 1933's King Kong, he was so stunned by the special effects skill in display throughout the film, he got a personal copy (which back then was extremely unheard of) and reverse-engineered how they pulled off the screen magic which brought to life such a unique project. With this, his own experience working at "Toho Motion Picture Company", getting drafted into WW2 as part of the propaganda department, and surviving through Tokyo's fire bombing, Eiji would go back to work in Toho MPC after US occupation ended in 1952, funnily enough the US government was keeping a close eye on him since they thought he was commiting espionage.

His position in Toho MPC would eventually place him squarely in the special effects team of Toho Tokyo Studios, working in a film called Godzilla (Gōjira), releasing in 1954. As we all know now, the original Godzilla is one of the most important films of recent history, and probably the single most important film special effects wise along with King Kong and 2001: A space odyssey. The impact this film would have culturally as well in Japan cannot be understated, the message of the atomic bomb and it's unstoppable consequences, shown through the giant Godzilla destroying everything in his wake, like a force of nature claiming what's rightfully theirs (which we've seen in the course, Japan really respects nature and it's strength), it's for a lack of a better word, utterly monstrous.

All of this we've gotta consider, barely 9 years after the atomic bombing of Japan back in 1945, it paints a grim picture of Japan's psyche and moral towards the world, Godzilla was after all a byproduct of humanity's lack of awareness, and recklessness, Godzilla is just in a way karma slapping back at it's creators. At the end of the movie he is defeated through a new even deadlier weapon than the one which created Godzilla, the oxygen destroyer. Even in the film, Dr Daisuke Serizawa says he cannot allow anyone to use the oxygen destroyer, his reasoning is in this direct quote from the film:

"Ogata, if the Oxygen Destroyer is used even once, politicians from around the world will see it. Of course, they'll want to use it as a weapon. Bombs versus bombs, missiles versus missiles, and now a new superweapon to throw upon us all! As a scientist - no, as a human being - I can't allow that to happen!"

Serizawa's life's work, used against a monster of mankind, just to create another monster in the massively destructive Oxygen Destroyer, tragic and sad. Even though he expresses his desire against using it, it's used nonetheless, since without it, Godzilla can't be defeated. To prevent the usage of this weapon in the future, Serizawa burns all his research on it, sadly since the information is still in his brain, he gets nearby the explosion when it's used against Godzilla, killing himself in the process. After this, Godzilla's bare bones can be seen floating deep in the pacific ocean, a bitter and depressing victory to be sure, right?

After finishing work on this movie, eventually in early 1966, a show called "Ultra Q" (Urutora Kyū) would release, produced by Tsuburaya productions. This tokusatsu (which basically means special effects show) series would gain a lot of attention since it had a lot of effort and budget put into it, at this time, there were only movies with this level of production, and it WAS the most expensive television show ever produced in Japan in its release date. The show follows different groups of scientists encountering supernatural anomalies, akin to the american Twilight Zone, the Q in the name "Ultra Q" stands for question, and yeah, it did leave a lot of questions, mysterious and horror-like stories would happen in each episode, growing ever more impossible to overcome, but they always got dealt with, in one way or another, no matter the cost, be it aliens, giant monsters (kaju) or even ghosts. Despite not featuring any giant metal hero, Ultra Q still counts as the first in the Ultraman series. Only two weeks after the end of this series, the title of this post would arrive to japanese houses and forever engrain himself in the hearts of Japan and anyone who saw it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hSgBCi-1yQE&ab_channel=荒城嶺

With this cheerful opening, Ultraman started airing on July 17, 1966. From the start we can already see a huge shift from Ultra Q, the colors in the beginning are from the Ultra Q opening, which then get rudely blown off the screen by the bright red and white, a band starts playing their instruments as the kid's choir starts singing:

"The mark in his chest is a meteor,

He beats down the enemies proudly with his jet.

From the Land of Light for the sake of us,

Here he comes, our hero Ultraman.

The capsule in his hand sparkles and flashes,

The radiance of a million watts.

From the Land of Light for the sake of righteousness,

Here he comes, our hero Ultraman.

The gun in his hand buzzes out "za-zap",

He is an expert at monster extermination.

From the Land of Light for the sake of the Earth,

Here he comes, our hero Ultraman."

Imagine being a kid, back then, and hearing this at the start of this new series, before you even see this Ultraman, you know he's already EXTREMELY powerful, like, he has a meteor in his chest? The radiance of a million watts? I cant count that high! He's also an expert at MONSTER EXTERMINATION? He fights for us, righteousness AND Earth? This guy is the best!

After this beautiful song, the actual first episode starts, called "Ultra Operation No. 1". The first thing we see is space, and shortly after two meteors following each other, a red one and a blue one, moments later, we cut to a jet flying through what seems to be a dense forest, here the narrator starts speaking about the Paris-based, International Science Police Organization, in it's japanese branch, there is a group dubbed the Science Special Search Party with 5 members, one of which we see piloting the jet, our protagonist, Shin Hayata. The narrator then tells us this group's goal is to protect Earth from any invasion from space, and investigate any weird incidents which may be related to aliens, it is implied this happens in the same universe as Ultra Q, so aliens and the like are relatively accepted to exist. Hayata then spots two UFOs flying over Ryugamori, he calls to base and Akiko Fuji, the sweet and caring communications officer responds, she calls out to Toshio Muramatsu, the ironclad stoic captain of the group, who tells Hayata to follow the UFOs to find out what they are. Here we also meet Daisuke Arashi, the strong sharpshooter with a soft spot, and also Mitsuhiro Ide, the genius coward of the group, who's also the source of most of the show's comedic relief.

Hayata notes the meteors are going at mach 2, which is twice the speed of sound, no small feat for a random UFO, then we cut to a group of people gathered around a makeshift campfire in the middle of the forest, singing songs, eating and dancing, they are then shocked by the huge blue sphere, lowering itself into the lake and flashing blinding light, they try to get a camera to photograph it, but the cameraman is too slow, right after this, Hayata flies by the lake with his jet, but suddenly the red sphere flies in at super speed, and crashes into Hayata, Hayata screams in terror before being hit, but he can't do anything to stop it. Both the jet and the red sphere crash into the ground, the bystanders go to check, and call the police after they see the wreck, then the police calls the SSSP headquarters to inform them of the emergency and the crash, the other members call Hayata, terrified for their wellbeing, and they get no answer. Fearing the worst, the science patrol gets in uniform, and moves out to the wreck in another jet. We cut to the police and campers, walking to the wreck, where they see Hayata floating into the air, and being wrapped in a red sphere, it floats higher and higher into the air, right after, we see Ultraman for the first time, talking to Hayata's still body.

Hayata asks who the hell is he, and Ultraman replies "I am an alien from Nebula M78", then Ultraman explains he was chasing Bemular (the blue sphere) who was escaping, the pursue ended up in Earth, Hayata asks confused about who this Bemular is, Ultraman explains he's a demon-like monster who disrupts peace in the universe. Ultraman apologizes to Hayata for, well, killing him in the most spectacular fashion, and in return offers his own life to Hayata, obviously our protagonist is shocked by this, and asks what'll happen to him, worried about this alien who literally just killed him, Ultraman explains he will become one with Hayata, as he himself also wishes to work for peace on Earth. The giant drops an object on Hayata, the beta capsule, he explains Hayata should only use it when he's in trouble, just as he's about to tell him why, Ultraman just laughs and tells him there's nothing to fear. we cut to the cops and campers, looking dumbfounded at the sphere, so dumbfounded in fact, this is the face of the police officer in command:

A huge flash from the red sphere blinds the crowd momentarily, then the SSSP arrives to check on them, and assess the situation, they see the wreck and dont think Hayata could've survived that, they keep checking on the civilians and trying to find out what lowered itself into the lake, we cut to an early sunny morning, suddenly Bemular emerges from the lake, and roars, the SSSP fires at the monster with their laser guns that go za-zap, the monster submerges itself again, just as Hayata calls to HQ to ask Akiko to drop a submarine into the lake so he can use it, he tells her he's fine and that she shouldn't worry, as soon as she drops it, the SSSP patrol sees her and asks what she's doing, she tells them Hayata called her and they can't believe it, but suddenly, Hayata appears in a boat, going towards the submarine, Hayata tells them that the alien saved him, and that they need to take care of Bemular before anything else, confused the captain agrees, and Hayata goes on to board the submarine and attack Bemular while he rests, the patrol joins Akiko in the sky with the VTOL jet, Hayata finds Bemular and the captain announces that Ultra Operation No.1 has started, the patrol attacks Bemular both from the sky and the water, it's going well until Bemular grabs the submarine Hayata is in, the jet keeps attacking so the monster lets Hayata go, Bemular gets out of the water into land, and let him go he does, Hayata falls from 60 meters onto the ground, knocking himself out, waking up in the submarine as Bemular shoots a beam to the submarine, Hayata notices himself in a bit of trouble, and heeds Ultraman's words, this is the first fight of Ultraman:

https://youtu.be/tP05cLPgRpI?si=vlMtAVQOYM1MO7oL&t=1202

Whilst this looks undoubtedly goofy and silly at this time, back then, this, was CINEMA, like incredibly good for the standards of japanese television in the 1960s, the music is triumphant, energetic, powerful, Ultraman really makes short work of the monster, saving the day as he would do for 39 episodes (counting this one), after the fight, Hayata goes back to meet his comrades, and tells them about the alien, the episode ends, and with this, we have the general structure of most episodes. The world is normal, then an alien/monster appears, something bad happens, the patrol is called upon, the patrol tries to fix the issue to variable results, and then finally, Ultraman appears and deals with the enemy, most times anyway. If you watched the fight (which you should), you'll see Ultraman has a 3 minute timer on Earth, which limits him and his fights, is he to be on our earth for longer than that, he will die, his beam attacks and special abilities drain his timer quicker, making them last resource weapons. Many times throughout the series, specially to the latter end of the story, Ultraman struggles with his fights, but he always comes out victorious, right?

Here are a collection of images ofUltraman fighting some monsters:

I will also link some of the most popular fights so you can get a sense of what it was like:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=879Q6KvyETU&ab_channel=Asefchanelrock

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ASrioLHfmQ&ab_channel=GodzillaBrasil

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F5O8j8NcGo8&ab_channel=Mega-Ip-Man

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xciM9KDJ1uI&ab_channel=KemurianSeijinUF

In the third image I put right above, the suit used for the monster is just a Godzilla suit with some stuff slapped on top, which is funny, since Ultraman's whole message is kind of the opposite of Godzilla's, a message of hope for the future and progress, instead of wallowing in the past of our mistakes. Whilst in Godzilla the monster destroyed everything and had to be defeated by another monster (the oxygen destroyer), in Ultraman, the monster is defeated by a hero, a symbol of hope and peace, and human ingenuity as well, the monster is a threat for sure, a big one, and sometimes it's hard to deal with, but it's always dealt with in the end, and everyone can go home with hope for the new tomorrow. Kids are also a huge part of Ultraman and tokusatsu in general, they're the future of the world, there's a kid in Ultraman, Isamu Hoshino, who hangs around the SSSP and follows them on missions whenever he can, he is always the top priority to be protected when they're out on missions, but he's also taught a thing or two in combat and protecting others, he is the future of the science patrol after all. Whenever people see Ultraman, they know it's about to be good, they know everything is alright, and that the monster is going to be absolutely DEMOLISHED. Ultraman's music is also a great part of this, always triumphant, and sometimes worrysome and eerie, making us fear for our hero, but it doesnt matter, he always wins. Here I'm gonna put a couple of songs so you can kinda understand what I mean.

The Science Patrol theme: https://youtu.be/T2TEqamHwZs?si=Pg-3_AbNE58aGH-t&t=683

Fight theme: https://youtu.be/T2TEqamHwZs?si=qEgqHSFcPL7HktUf&t=944

Aerial battle theme: https://youtu.be/T2TEqamHwZs?si=HfqmzQzsfZ4VT9pr&t=1627

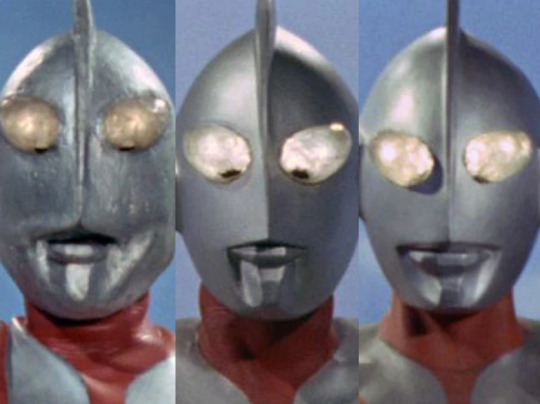

(Note the difference between Ultraman's ground battle theme, and his air battle theme, never once in the series is Ultraman bested in aerial combat, so his aerial combat theme is much more triumphant, almost like a guaranteed win, this could be due to Ultraman's natural flying skill, or maybe Hayata's expertise as a jet pilot, maybe both! Throughout the series it is implied Ultraman becomes more and more human, this is shown with the changes in the suit, first to last, from left to right)

(Notice his face becoming rounder, smoother, proportions getting more, well, human, the actual real world explanation is they just got better at making suits LMAO, but I love the in-universe explanation, btw, first mask was supposed to be able to move it's mouth, that's why it has that hole, though they eventually scrapped that idea, and just sew shut the hole, leaving it like that)

Victory! M5 (as the name implies, when this plays, Ultraman is about to win) :https://youtu.be/T2TEqamHwZs?si=kBxMBmB6j_Dqb18z&t=1515

In episode 39, Ultraman fights against Alien Zetton, the champion of the Zetton aliens, a race of invaders from outer space, threatening planet Earth and the whole galaxy if they aren't stopped, they arrive on Earth to challenge the galaxy's best defender, Ultraman, the decisive battle begins, just outside of SSSP's Headquarters, Hayata transforms, and prepares to fight the mighty Zetton:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-5zsi4s3N7g&ab_channel=KemurianSeijinUF

Ultraman, defeated at last, after so many monsters and battles, he is felled by Zetton, the strongest kaiju yet, everyone looks in horror as Ultraman falls to the ground, is this it? Is humanity to die? No, Ide created a device, a weapon, strong enough to theoretically defeat Zetton, as their last hope, Arashi the sharpshooter, takes aim at Zetton, and fires, killing the great monster who defeated Ultraman. After so many times Ultraman protected Earth from certain doom, humanity saved itself. A powerful message, that humanity even facing the worst danger, can rise up to the ocassion by themselves, and overcome the problem, we're our own hope. But of course this doesn't mean Ultraman wasn't necessary, he guided the patrol, if it weren't for him, the patrol wouldn't have had the strength to rise up so many times from certain failure.

After this, Ultraman Zoffy, from Nebula M78 arrives, and takes Ultraman back home, separating him from Hayata, leaving them both better people than they started, and making sure they never forget this journey. The whole series is in my own opinion a great story, filled with cool fights, interesting plots, and amazing messages, of course it would get a sequel, in 1967, Ultraseven released, going back to the darker tone of Ultra Q, but nonetheless, having the spirit of Ultraman, a hero that inspires others. Ultraman's influence on Japan cannot be understated, he's arguably more important than Godzilla for a lot of people over there, he's a central part of Japanese pop culture, and even today it still releases series, the most current Ultraman, called Ultraman Blazar, is currently airing, with great success as always, almost 45 series have been aired on japanese TV under the name Ultraman, and a ton of movies too. Recently, Hideaki Anno of Evangelion fame, released a movie called "Shin Ultraman", a refreshed take on the old japanese hero, he's also released Shin Godzilla and Shin Kamen Rider, all icons of tokusatsu culture, he's a big fan of it himself of course, even Evangelion, his most known work, was heavily inspired by Ultraman in his own words. Netflix just released the third and final season of Ultraman's anime as well, and the manga is currently ongoing too, figures sell like hot bread in hobby stores, and references to Ultraman keep popping out everywhere, it is going to be Ultraman's 60th anniversary in 3 years time, crazy to think of, such a long running series, still peaking in popularity in it's home country.

I cant do justice to all of the Ultraman lore and story ever I think, no matter how many words I write or speak, but I hope this post got people interested in Japan's giant of light, and hopefully, you'll check it out on your own free time, throughout all the series there's something for everyone, I personally recommend checking out Ultraman, Ultraseven, Ultraman Leo, Ultraman Tiga, Ultraman Mebius and Blazar. I for one cannot express how important he is to me, he is the first japanese media I ever saw, my dad was a great fan when he was a kid, back when it aired on TV in the late 70s here in Chile, so he got me some DVDs to watch when I was a kid, and enough said, I loved it, even now I love Ultraman, as an eighteen-year old university student, his message of hope for the future and to strive to be our best version is truly inspiring to me, specially from such a country, when most of their popular media is well, kinda depressing, Ultraman shines ever bright as a beacon of light for everyone who's willing to try to do the right thing, and to everyone who hopes for a better future. Thanks for reading, and I hope you have a great day.

SHUWATCH!

Post by Javier Salinas-

1 note

·

View note

Text

#kaiju no. 8#kaiju no. 8 spoilers#eiji hasegawa#gen narumi#narumi gen#jura igarashi#soshiro hoshina#soshiro#hoshina#mina ashiro#juugo ogata#naoya matsumoto

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

長い散歩 [A Long Walk] (Eiji Okuda - 2006)

#長い散歩#A Long Walk#Eiji Okuda#Nagai sanpo#2000s cinema#2000s#2000s movies#Ken Ogata#Hana Sugiura#Saki Takaoka#Shôta Matsuda#movies#cinema of Japan#Japanese cinema#Japanese drama films#Japan#cinema#Asian movies#Asian cinema#fall#autumn#autumn leaves#trees#nature#red#yellow#colours#colors#beauty

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Banana Fish VAs

Yuuma Uchida: Ash Lynx

Kenji Nojima: Eiji Okumura

Ayumu Murase: Skipper

Shinji Kawada: Shunichi Ibe

Hiroaki Hirata: Max Lobo

Unshō Ishizuka: "Papa" Dino Golzine

Yoshimasa Hosoya: Frederick Arthur

Toshiyuki Morikawa: Blanca

Jun Fukuyama: Yut-Lung Lee

Makoto Furukawa: Shorter Wong

Shōya Chiba: Sing Soo-Ling

Sōma Saitō: Lao Yen-Tai

Mitsuru Ogata: Jenkins

Yōji Ueda: Charlie Dickenson

#voice actors#anime voice acting#yuuma uchida#kenji nojima#shinji kawada#hiroaki hirata#unsho ishizuka#hosoya yoshimasa#toshiyuki morikawa#jun fukuyama#makoto furukawa#shoya chiba#soma saita#mitsuru ogata#yoji ueda#banana fish#ash lynx#bananafish#eiji okumura#okumura eiji#shorter wong#yut lung#sing soo ling#blanca#max lobo#shunici ibe#ayumu murase

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

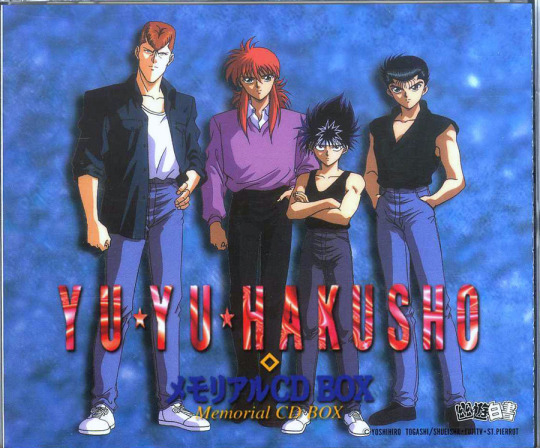

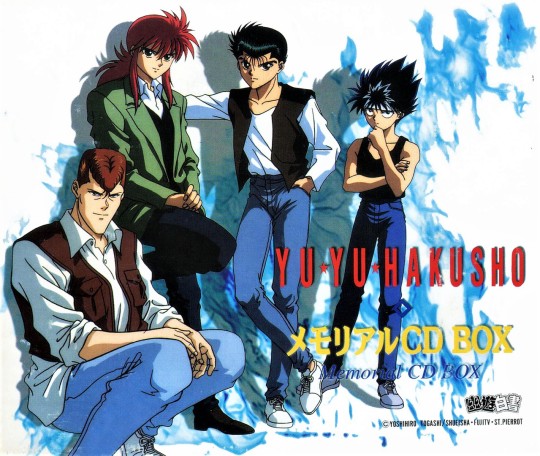

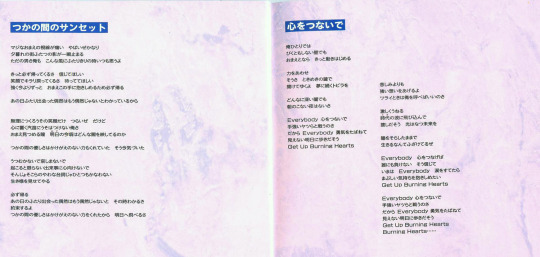

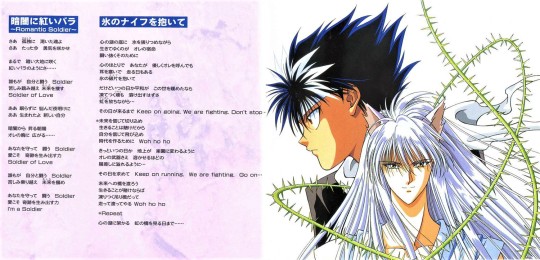

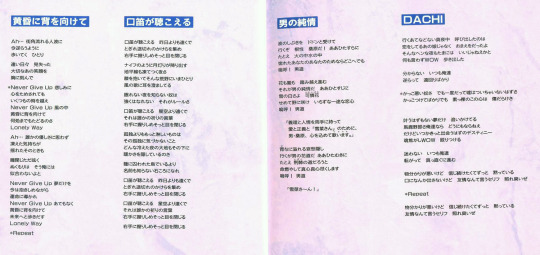

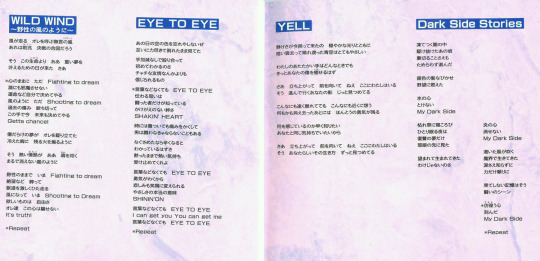

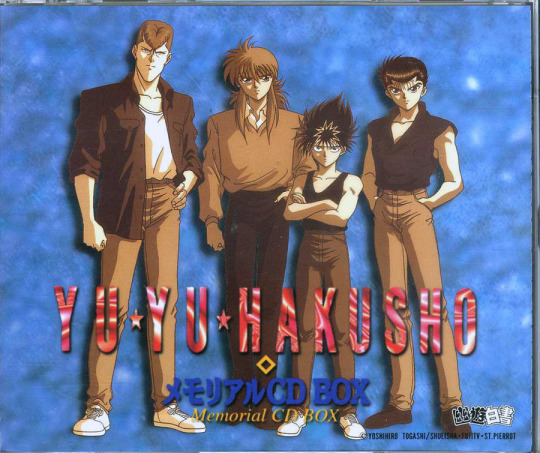

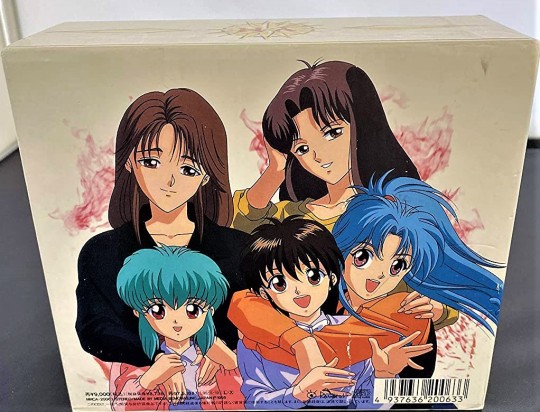

Yu Yu Hakusho Memorial CD BOX (1995)

「幽★遊★白書」メモリアル CD BOX

A collector's item that covers 74 songs in a commemorative box containing 6-discs. Most of the image songs can be found in the Yu Yu Hakusho Music Battle Editions 1, 2 and 3.

In addition to the conventional songs, [Disc 6] contains Part 2 of the Yu Yu Special Mini Drama “Warrior Hunger”. Part 1 is recorded in the “Music Battle Edition 2″. Both parts were written and directed by Shigeru Chiba, Kuwabara’s voice actor.

[Disc 1]

Yusuke, Kuwabara, Kurama and Hiei Image Songs.

TRACKLIST

01. ファイアー! [Faiaa!] “FIRE!” by Yusuke Urameshi (Nozomu Sasaki)

02. つかの間のサンセット [Tsukanoma no Sunsetto] “Fleeting Sunset” by Yusuke Urameshi (Nozomu Sasaki)

03. 心をつないで [Kokoro wo Tsunaide] “Connect your Heart” by Yusuke Urameshi (Nozomu Sasaki)

04. タフ “TOUGH” by Yusuke Urameshi (Nozomu Sasaki)

05. デッド・オア・アライヴ~闘神 [Dead or Alive~Toushin] “Dead or Alive ~ Fighting God” by Yusuke Urameshi (Nozomu Sasaki)

06. 暗闇に紅いバラ~ロマンティック・ソルジャ [Kurayami ni Akai Bara ~ Romantikku Sorujā)] “Red Rose in the Dark ~ Romantic Soldier” by Kurama (Megumi Ogata)

07. 氷のナイフを抱いて [Koori no Naifu wo Daite] “Holding the Ice Knife” by Kurama (Megumi Ogata)

08. 第3の目 [Daisan no Me] “Third Eye”

09. 黄昏に背を向けて [Tasogare ni Se wo Mukete] “Turn Your Back to the Twilight” by Hiei (Nobuyuki Hiyama)

10. 口笛が聴こえる [Kuchibue ga Kikoeru] “I can heart a Whistle” by Hiei (Nobuyuki Hiyama)

11. 男の純情 [Otoko no Junjou] “Man's Innocence” by Kazuma Kuwabara (Shigeru Chiba)

12. ダチ “DACHI” by Kazuma Kuwabara (Shigeru Chiba)

[Disc 2]

Image Songs from the female cast and duets.

TRACKLIST

01. ワイルド・ウインド~野性の風のように [Wild Wind ~ Yasei no Kaze no Yooni] “WILD WIND ~ Like a Wild Wind” by Kurama & Hiei (Megumi Ogata & Nobuyuki Hiyama)

02. アイ・トゥ・アイ “EYE TO EYE” by Kurama & Hiei & Kazuma Kuwabara (Megumi Ogata & Nobuyuki Hiyama & Shigeru Chiba)

03. イェル “YELL” by Keiko Yukimura (Yuri Amano)

04. ダーク・サイド・ストリーズ “Dark Side Stories” by Hiei & Youko Kurama (Nobuyuki Hiyama & Shigeru Nakahara)

05. ホールド・アウト! “HOLD OUT!” by Botan & Keiko Yukimura & Yukina (Sanae Miyuki & Yuri Amano & Yuri Shiratori)

06. どんな時でもあなたと目覚めたい [Don'na Toki Demo Anata to Mezametai] “I want to wake up with you at any time” by Keiko Yukimura (Yuri Amano)

07. ラヴ・ソングをあなたに [Love Song wo Anata ni] “Love Song for You” by Cult Girls: Koto, Juri, Ruka (Ai Orisaka, Katsuyo Endo, Chiharu Suzuka)

08. 思い出を翼にして [Omoide wo Tsubasa ni Shite] “Turning Memories To Wings” by Yusuke Urameshi & Keiko Yukimura (Nozomu Sasaki & Yuri Amano)

09. ロケット花火のラヴ・ソング [Roketto Hanabi no Love Song] “Rocket Fireworks Love Song” by Kazuma Kuwabara & Yukina (Shigeru Chiba & Yuri Shiratori)

10. トコトン “TOKOTON” by Koenma (Mayumi Tanaka)

11. ムーンライト・パーティ “Moonlight Party” by Koenma & Botan (Mayumi Tanaka & Sanae Miyuki)

12. 永遠のレクイエム [Eien no Requiem] “Eternal Requiem” by Shinobu Sensui & Itsuki (Rokuro Naya & Kooji Tsujitani)

[Disc 3]

Villains and Supporting Characters Image Songs.

TRACKLIST

01. マーダー・マーチ “MURDER MATCH”

02. アイシー・ブラッド “Icy Blood” by Younger Toguro (Tessho Genda)

03. グリーム~闇に光る [GLEAM~Yami ni Hikaru] “Darkness in the Light” by Touya (Yasunori Matsumoto)

04. つむじ風でフライアウェイ [Tsumuji Kaze de Fly Away] “Fly Away With the Whirlwind” by Jin (Kappei Yamaguchi)

05. 美しすぎて… [ Utsukushi Sugite...] “Too Beautiful...” by Beautiful Suzuki (Kazuyuki Sogabe)

06. まあ、飲めよ [Maa, no Me Yo] “Well, drink by Chuu” (Wakamoto Norio)

07. アンビリーヴァブル “UNBELIVEABLE” by Shinobu Sensui (Rokuro Naya)

08. ネヴァー・エンディング・ドリームス “Never Ending Dreams” by Itsuki (Kouji Tsujitani)

09. 霧の中の狙撃手 (スナイパー) [Kiri no Naka no Sunaipaa] “Sniper in the Fog” by Kaname Hagiri (Eiji Sekiguchi)

10. バトル・パワー! “BATTLE POWER!”

11. クライ・ロンリー・クライ “Cry Lonely Cry” by Younger Toguro (Tessho Genda)

12. リバース~再生 [REBIRTH ~Saisei] “REBIRTH” by Mukuro (Minami Takayama)

13. 千年の闇の果て [Sennen no Yami no Hate] “The End of a Thousand Years of Darkness” by Yomi (Masashi Ebara)

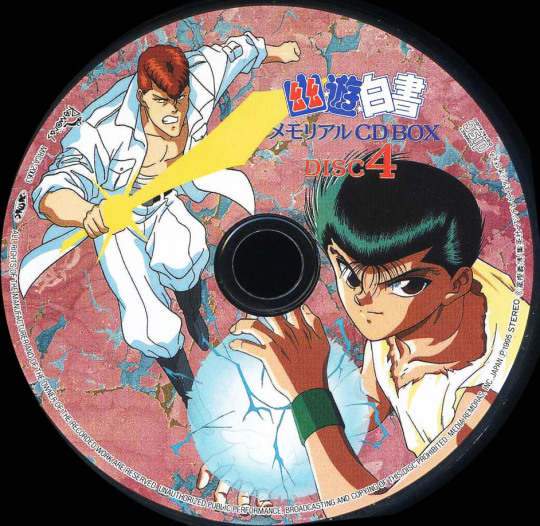

[Disc 4]

Opening & Ending Themes and 3 songs sung by the main cast.

TRACKLIST

01. 微笑みの爆弾 [Hohoemi no Bakudan] “Smiling Bomb” by Matsuko Mawatari (Opening Theme)

02. ホームワークが終らない [Homework ga Owaranai] “The Homework doesn’t End” by Matsuko Mawatari (1st Ending Theme)

03. アンバランスなキスをして [Anbaransu na Kisu wo Shite] “ An Unbalanced Kiss” by Hiro Takahashi (2nd Ending Theme)

04. さよならバイバイ “Sayonara Bye Bye” by Matsuko Mawatari (3rd Ending Theme)

05. 太陽がまた輝くとき [Taiyou ga Mata Kagayaku Toki] “When the Sun is Shining Again” by Hiro Takahashi (4th Ending Theme)

06. デイドリーム・ジェネレーション “Daydream Generation” by Matsuko Mawatari (5th Ending Theme)

07. 見えない未来へ [Mienai mirai e] “ Towards the Unseen Future” by Yusuke Urameshi, Kazuma Kuwabara, Kurama, Hiei, Keiko Yukimura, Botan, Yukina and Koenma (Nozomu Sasaki, Shigeru Chiba, Megumi Ogata, Nobuyuki Hiyama, Yuri Amano, Miyuki Sanae, Yuri Shiratori & Mayumi Tanaka)

08. 優しさは眠らない [Yasashisa wa Nemuranai] “Kindness Never Sleeps” by Yusuke Urameshi, Kazuma Kuwabara, Kurama, Hiei (Nozomu Sasaki, Shigeru Chiba, Megumi Ogata, Nobuyuki Hiyama)

09. 光の中で [Hikari no Naka de] “In The Light” by Yusuke Urameshi, Kazuma Kuwabara, Kurama, Hiei (Nozomu Sasaki, Shigeru Chiba, Megumi Ogata, Nobuyuki Hiyama)

10. 微笑みの爆弾 (インストヴァージョン) “Hohoemi no Bakudan (Intrumental Version)”

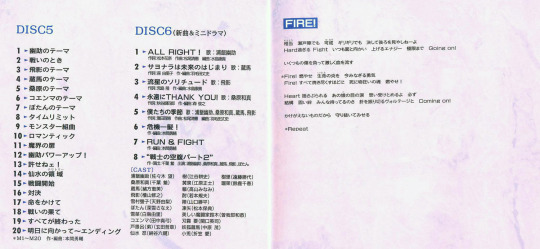

[Disc 5]

Background Music - BGM (Composition and Arrangement: Yusuke Honma).

TRACKLIST

01. 幽助のテーマ “Yusuke’s Theme”

02. 戦いのとき [Tatakai no Toki] “Time of Battle”

03. 飛影のテーマ “Hiei’s Theme”

04. 蔵馬のテーマ “Kurama’s Theme”

05. 桑原のテーマ “Kuwabara’s Theme”

06. コエンマのテーマ “Koenma’s Theme”

07. ぼたんのテーマ “Botan’s Theme”

08. タイムリミット “Time Limit”

09. モンスター組曲 [Monster Kumikyoku] “Monster Suite”

10. ロマンティック “Romantic”

11. 魔界の扉 [Makai no Tobira] “Makai’s Door”

12. 幽助パワーアップ! “Yusuke Power Up”

13. 許せねェ! [Yuruse nee!] “I Won’t Forgive You!”

14. 仙水の領域 (テリトリー) “Sensui’s Territory”

15. 戦闘開始 [Sentou Kaishi] “Battle Starts”

16. 対決 [Taiketsu] “Showdown”

17. 命をかけて [Inochi wo Kakete] “Risk Your Life”

18. 戦いの果て [Tatakai no Hate] “The End of Battle”

19. すべてが終った [Subete ga Owata] “It’s All Over”

20. 明日に向かって~エンディング [ Shitanimukatte ~ Ending] “Towards Tomorrow ~ Ending”

[Disc 6]

Yusuke, Kuwabara, Kurama & Hiei Image Songs + 2 BGM and Part 2 of the “Warrior Hungry” Mini Drama recorded for this box.

TRACKLIST

01. オール・ライト! “ALL RIGHT!” by Yusuke Urameshi (Nozomu Sasaki)

02. サヨナラは未来のはじまり [Sayonara wa Mirai no Hajimari] “A Goodbye is the Beginning of the Future” by Kurama (Megumi Ogata)

03. 流星のソリチュード [Ryuusei no Solitude] “Solitude Of a Falling Star” by Hiei (Nobuyuki Hiyama)

04. 永遠にサンキュー! [Eien ni THANK YOU!] “Thank You Forever” by Kazuma Kuwabara (Shigeru Chiba)

05. 僕たちの季節 [Bokutachi no Kisetsu] “Our Season” by Yusuke Urameshi, Kazuma Kuwabara, Kurama, Hiei (Nozomu Sasaki, Shigeru Chiba, Megumi Ogata, Nobuyuki Hiyama)

06. 危機一髪! [Kikiippatsu!] “Critical Moment!” (Composition and Arrangement: Yusuke Honma)

07. ラン&ファイト “RUN & FIGHT” (Composition and Arrangement: Yusuke Honma)

08. 戦士の空腹パート2 (ミニ・ドラマ) [Senshi no Kuufuku Part 2 ~ Mini Dorama] “Warrior Hungry Part 2 (Mini Drama)”. Written and Directed by Shigeru Chiba. By Yusuke Urameshi, Kazuma Kuwabara, Kurama, Hiei, Botan (Nozomu Sasaki, Shigeru Chiba, Megumi Ogata, Nobuyuki Hiyama, Sanae Miyuki).

BOOKLET

Comments from the Japanese Voice Actors (translation):

#「幽★遊★白書」メモリアルCD BOX [6CD]#yu yu hakusho memorial cd box#kurama#megumi ogata#hiei#nobuyuki hiyama#Yusuke Urameshi#nozomu sasaki#kazuma kuwabara#shigeru chiba#botan#keiko#yukina#koto#juri#ruka#chuu#jin#touya#beautiful suzuki#mukuro#yomi#shinobu sensui#itsuki#Naya Rokurou#toguro#matsuko mawatari#Hiro Takahashi#yusuke honma#youko kurama

487 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monster Monday: Godzilla

Well, I’ve decided to do it.

I’m going to go through every Kaiju movie that Toho has put out, front to back. We’re in that phase of quarantine y’all, and I’ve got an entire shelf full of these. I’ll try to keep the general structure of these write-ups fairly similar, with an overview and review of the movie, along with how I watched it and if I’ve seen it before.

So we might as well start at the beginning, and that beginning is of course, 1954′s Godzilla, or Gojira if you prefer the Japanese pronunciation. With 36 Japanese-language releases and two American remakes, along with multiple cartoon shows, the Godzilla series is one of, if not the longest-running film series out there, and it was starting up what we’d now call a “cinematic universe” way before Nick Fury showed up at the end of the first Iron Man.

Toho, the studio behind the Godzilla series also made other kaiju movies, and by the fourth Godzilla sequel they started tying these other creatures into their cash cow franchise, and before you knew it, there was a whole continuity. There have been different directors, writers, actors, monsters, you name it, but Godzilla himself is always a constant. While the continuity may at times be tenuous or outright bizarre, it is very much present, and it's what makes these movies so fun.

Though you won’t see any of that in the original Godzilla. Aside from possibly Shin Godzilla, there’s no other Godzilla movie that even comes close to the original, either in its bleak tone or in its stellar quality. This is probably my fourth or fifth time with the original Godzilla, and this time around I watched it on the 15-film Criterion set, though there’s also a single DVD/Blu Ray release of the Criterion edit as well.

The film begins with a fishing ship being destroyed by a strange, bright flash from under the sea. No ones survives, and countless more ships go missing, (in a fashion that absolutely evokes the Lucky Dragon incident, which in 1956 was still a painful memory) and a vicious typhoon strikes nearby Odo Island, an expedition travels there to try and find out what’s happening. Among the crew are three of our main characters, Ogata, a salvage ship captain, (Akira Takarada) his girlfriend Emiko, (Momoko Kochi) and her father and renowned paleontologist Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura). The trio encounter Godzilla, who rampages through the island before returning to the sea.

Yamane presents his research back in Tokyo, concluding that Godzilla is an ancient dinosaur disturbed by H-Bomb testing. Lines are drawn, with many wanting to kill the creature, and others, prominently Yamane, who wish to leave the creature be and study it. This conflict brings in our fourth protagonist, Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata) a reclusive scientist working on a dangerous project.

Afterwards, Godzilla attacks Tokyo, first briefly and then in full force, destroying buildings and incinerating countless civilians with his atomic breath. Nothing the military does has any effect on the beast, and he levels huge swaths of the city before returning to the sea. In the aftermath of the attack, scores of people are dead and even more are sickened with radiation poisoning. Emiko and Ogata convince Serizawa to use his creation, a weapon known as the oxygen destroyer, to try and kill Godzilla. Ogata and Serizawa dive into the sea and release the oxygen destroyer, after which Serizawa cuts his line to the ship and dies with the monster, so that his research can never be used again.

The film itself is a grim, bleak metaphor for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with a giant radioactive dinosaur standing in for the atomic bombs. The carnage Godzilla causes is played completely straight - hospitals are crowded with victims, and in one poignant scene that eventually wins over the reticent Serizawa, a children’s choir sings a stirring dirge for the dead, and it’s a scene that can’t help but stay with you.

Ishiro Honda’s direction is the deft, with sweeping shots of Godzilla that convey power and menace that none of the sequels can match up to. Scenes of Tokyo burning with Godzilla silhouetted against the flames have a chilling effect, and the camera lingers on them for just the right amount of time.

The stirring, bombastic score by Akira Ifukube deserves special mention as well. Many of the themes that would become franchise classics were born here, and they have an optimistic, brassy quality that lend excitement to the military scenes, as well as dread to the scenes of destruction.

Eiji Tsuburaya’s effects work is also stellar, especially considering this was their first real test of what would become a winning formula. The model cities are top notch, though there are a few shots of falling cars and trucks that have a toy-like quality to them, they’re gone in seconds and don’t detract from the experience. The Godzilla suit itself, a 220 lb beast that suit actor Harou Nakajima could only wear for around three minutes at a time without fainting, looks fantastic, though it’s clearly bulky and difficult for the actor to move in. The same praise can’t be given to the hand puppet used for the close ups of Godzilla, which looks clearly nothing like the suit and is really the only outright failure of the film. Later sequels would handle it better, so it’s difficult to fault the team too much when they were still finding their feet.

Overall, the original Godzilla is a tour de force, and it’s damn hard to find anything negative to say about it. The performances are great, and the human story draws you in, waiting for Godzilla to finally appear (though unfortunately his first on-screen appearance is in puppet form, which lessens the gravity a bit). The haunted Dr. Serizawa deserves a special mention here, a clear nod to the legacy of the atom bomb, he is torn apart by guilt that his invention (that he created on accident) could be used to cause yet more harm to the world. Dr. Yamane, in his desire to see Godzilla protected, is clearly wracked with pain seeing this creature that humanity unleashed have to die, yet he knows even more suffering will follow if it lives.

The story is tight and a joy to watch - there’s a palpable sense of dread whenever Godzilla is onscreen, and Nakajima moves slowly and deliberately, like a confused animal reacting to the world around him. Unlike many of the American monster movies from the same time period, the cast have sympathy for the monster, and there’s no great victory in killing it, only sadness both for the sake of Godzilla and Serizawa, who couldn’t bear to live in a world that would abuse his invention.

If you haven’t seen the original Godzilla, or if you’re more familiar with the campy 60s and 70s sequels like Godzilla vs. Megalon, do yourself a favor and watch this one. Clocking in at 96 minutes, there’s no scene wasted, and it’s a real thrill to see where the king of the monsters came from.

The film ends with a melancholy Dr. Yamane ruminating on the possibility of another Godzilla out there, waiting to be released if humanity continued its nuclear testing. That Godzilla, and not the original, would be back, much sooner than the good doctor expected.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Need You: Why Evangelion Still Matters

If you’re even a casual fan of Japanese animation (colloquially known as anime) you’ve probably heard of a few classics held up as the best of the medium; films and television shows whose place in the history of Japanese culture is widely regarded as secure: Akira, Cowboy Bebop, Ghost in the Shell, Spirited Away, to name a few of the most prominent. They all have their critics, but few would dispute their place as landmarks of the industry. But there’s one classic piece of Japanese animation however whose legacy is far more contentious and which sparks controversy even today. Like the aforementioned pieces it’s well-known and has been watched by many, but unlike them it remains quite controversial, beloved by some and derided by others.

I’m talking about Neon Genesis Evangelion,¹ Hideaki Anno’s 1995 post-apocalyptic series about teenagers who pilot giant robots (known as mecha) in a war for the survival of humanity. And in my opinion it’s actually one of the best and most important television shows of all time, animated or not.

(Spoilers ahead, though I’ll try to keep major revelations to a minimum.)

I realize that in making my claim, I’m setting myself up for criticism. The value (or lack thereof) of Neon Genesis Evangelion has been one of the most heated debates in anime fandom for decades. But even on the purely objective level of its influence on the animation industry, both in Japan and beyond, NGE and its subsequent spin-offs, sequels, and re-imaginings is a significant work worth consideration. Although the show is decades old now (the first episode aired October 4, 1995), I believe it’s still worth examining why the show’s so acclaimed and why, in my opinion, it’s still relevant today, in no smal part because of the lessons it still has to teach us about self-acceptance.

(An earlier version of this essay was posted 4 years ago here.)

Weaving a Story

Concept art for Asuka Langley Soryu, the Second Child

Today, Evangelion is a major franchise, incorporating films, comics, video games, and more. But it all started with one TV show, Neon Genesis Evangelion, created by Hideaki Anno for Gainax. Even from the start, NGE was somewhat exceptional. In the early-to-mid 1990s when it was produced, most of the major animated shows on air (both in Japan and America) were heavily merchandise-driven and sponsored by either toy or video game companies. Nearly all were owned by a major studio like Toei or Toho. Conceived of by a single individual and owned by a small creator-run studio, Neon Genesis Evangelion was highly unusual and something of a creative risk.

The story of Neon Genesis Evangelion is, on first glance, nothing remarkable for Japanese animation. A group of teenagers are recruited by a unified global government to pilot giant robots (mecha) in a battle for the survival of humanity. In the process they have to face not only their deadly adversaries but also learn how to work together as a team, overcoming their many differences and personal issues. Gundam, Macross, and Hideaki Anno’s own Gunbuster had all covered similar territory before. But where NGE would go with its premise was far stranger, blending the well-tread concept of adolescent soldiers with theological imagery, Freudian and Lacanian analysis, and abstract writing that soon set the show apart from its contemporaries.

The show quickly caught the fascination of viewers. While Neon Genesis Evangelion started initially with solid but unexceptional ratings, it soon expanded into a massive pop cultural phenomenon as more and more people tuned in to find out what all the fuss was about, eventually reaching 25-30% of the targeted demographic.² The final two episodes, noted for their abstract nature and for seemingly leaving several plot threads hanging, prompted a highly polarized reaction. The follow-up movie The End of Evangelion, released a year later, divided audiences even further. As a consequence, despite Evangelion’s immense popularity and influence, the franchise remains one of the most controversial works to ever air on broadcast television.

Neon Genesis Evangelion’s ending was, however, just one of its controversial aspects. Moral guardians raised complaints about the show’s frank (and frequently bleak) depictions of sex, violence, and mental illness, demanding networks censor its content. Critics such as Eiji Otsuka and Tetsuya Miyazaki accused Anno of “brainwashing” his audience and affirming, rather than criticizing, anime fans’ escapist tendencies. Yoshiyuki Tomino, the director of both Gundam and Ideon, complained that Anno tried “to convince the audience to admit that everybody is sick” and that it “told people it was okay to be depressed.” Additionally, much was made of the show’s religious imagery, particularly due to the then recent sarin gas attacks by the Aum Shinrikyo cult, which like NGE utilized a blend of Western and Japanese religious imagery.

Other complaints centered on NGE’s main characters, many of whom were found to be unlikeable or unheroic. Many attacked the lead protagonist Shinji as weak and indecisive, unbecoming of the hero in a show aimed at adolescents. Some further asserted the character was an attack on the show’s audience and that Anno wanted to “punish” his audience for their anime-loving ways. The rest of the cast didn’t escape criticism either and were variably found to be cruel, schizophrenic, or perverse. All could easily be characterized as dysfunctional.

But despite the backlash against Neon Genesis Evangelion, whether it was centered on the show’s ending, its thematic elements, or its characters’ deficiencies, none of it seemed to put a lasting dent in the show’s influence or popularity. And a lot of that, perhaps, has to do with the time in which it emerged. At the time NGE was originally produced in the early to mid 1990s, Japan was in the midst of an extended economic downturn that would come to be known as the Lost Decade, following a major asset price crash in 1989. During this time, Japanese animation, like many industries, experienced a contraction, resulting in slashed budgets and an increasing reliance on merchandising and product placement to sustain both the studios producing the content and the major networks who broadcasted (and often owned) it.

In addition to these economic concerns, there was also a growing feeling in the 1990s that animation was a thing of the past, whose glory days were long gone and which only inspired passion in either adolescents or callow, sheltered men in their 20s or 30s. The content of most anime was regarded as puerile or derivative and hardly becoming of serious adult interest. The term otaku,³ a word that literally means “house” but was used to mean “shut-in,” quickly became shorthand for anime fans who spent their adulthood collecting memorabilia and memorizing lines from their favorite shows.

But Neon Genesis Evangelion helped to change all that and to reclaim anime’s respectability. Breaking through the traditional animation fandom to a wider audience and owned solely by the creator-run Gainax, NGE was an invigorating shock to the industry, shaking it up and reviving interest in what had been regarded as a dying medium. Within a few short years, new creator-owned studios were cropping up across Japan, a trend which would continue well into the next decade and bear such fruit as Bones, manglobe, Ufotable, or Gainax’s own offshoots Trigger and Khara. The animation industry was expanding again and was beginning to boom overseas, in no small part thanks to the popularity and notoriety of NGE.

Devilman: Crybaby by Science Saru, a series itself based on one of Evangelion’s chief influences

The new anime boom would also reflect its origins in a number of different ways. More than a few of the new shows to debut in the late 1990s and early 2000s were directly influenced and impacted by Neon Genesis Evangelion, including such notables as RahXephon and Revolutionary Girl Utena. More subtly, the starkly realistic depictions of violence and sexuality in NGE as well as its bizarrely surreal imagery encouraged many directors to try similar techniques, resulting in a shift in style throughout the industry.

Neon Genesis Evangelion’s influence on later anime can be attributed in some ways to its technical sophistication. At its most basic, visceral level, NGE was startling to look at. Even compared with other Gainax works that had come before it, like Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water or Gunbuster, NGE immediately stood out as something unique in an increasingly homogeneous industry. The character designs of Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, strangely subdued yet striking and expressive, helped distinguish the cast while Ikuto Yamashita’s monstrous and biomechanical designs for the Evangelions did the same for the show’s mechs. Combined with the intense direction of Hideaki Anno, Kazuya Tsurumaki, Masayuki, and others NGE drew the eye right from the start.

The technical splendor wasn’t just limited to NGE’s art design or animation either. The voice talents provided by performers like Megumi Ogata, Kotono Mitsuishi, Megumi Hayashibara, and Yuko Miyamura gave life to the characters and helped audiences empathize with them, despite their dysfunctional and emotionally-wrought nature. Also contributing to the audio portion of Neon Genesis Evangelion was Shiro Sagisu, whose music swung significantly from jazzy to melodramatic and even to surreal, changing and evolving to match each scene with an appropriate mood. Assisting Sagisu was the vocal work of artists such as Yoko Takahashi, who made the show’s central theme, “A Cruel Angel’s Thesis,” a pop sensation.

But while the technical triumphs of Neon Genesis Evangelion certainly contributed to the show’s lasting appeal and influence, they’re hardly the whole story. For many viewers, the appeal of Evangelion went well beyond the surface, to narrative and thematic elements they felt spoke directly to them. Indeed, it is arguably NGE’s complex characterization, unorthodox narrative structure, and thematic depth which have made it stand out as one of the most legendary examples of Japanese pop culture.

A Cruel Angel’s Thesis

It’s not an exaggeration to say that essays—and books—have been written about Neon Genesis Evangelion and its thematic qualities. Most of this has been concentrated in Evangelion’s own native Japan, but the sensation has breached the other side of the Pacific as well, resulting in comparisons to the works of David Lynch and other Western directors. Contributing to this no doubt has been Anno’s own numerous references in NGE not only to native Japanese culture but to the West as well, with tributes to works like 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Andromeda Strain, and UFO found frequently throughout.

The most obvious thematic element present in Evangelion, at least to Western eyes, is its frequent allusions to Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. It’s not hard to see why: the monstrous foes besetting humanity are “Angels” who shoot cross-shaped energy bolts, which the main characters fight with “Evangelions” (the Greek word from which “evangelism” derives). Coupled with other bits and pieces here and there referring to original sin, the will of God, and ancient Judaism, these details give Evangelion a strikingly religious appearance to Western viewers.

However, while they’re certainly the most obvious elements in Evangelion, the religious references are also easily some of the most transient and insubstantial. Although initially viewed as central to the plot by many Westerners, it has since been revealed that most of the Biblical references are there for styling rather than substance and were largely intended to make the show stand out. In many respects, the usage of the Abrahamic faiths in Evangelion is similar to the use of Buddhism in The Matrix or Egyptian mythology in Stargate: a bit of fun exoticism to keep things interesting.

The Sephirot from Kabbalah, as represented in The End of Evangelion

That being said, the religious themes are not as vacuous as is sometimes alleged and the sheer number and obscurity of some of them indicates some real effort on the part of Anno. Each of the Angels, for instance, (which are called shito⁴ in Japanese, meaning “messenger” or “apostle”) are named after actual angels from Abrahamic mythology and their names, when translated from Hebrew or Arabic, often do indicate their nature in some way (e.g., Arael’s name means the “light of God” and it is an enormous winged being who attacks the characters with a beam of light). And while the use of the Kabbalah’s Sephiroth may be perfunctory, many other references to Jewish mysticism appear more meaningful, such as the Chamber of Guf or the duality of the Trees of Life and Wisdom.

Less obvious to Western eyes but possibly even more sophisticated are the references Evangelion makes to non-Abrahamic religions. There is, for example, the notable similarity between what the show terms “Instrumentality” and traditional descriptions of “egoless” nirvana in Buddhism (a religion also referenced by way of the Marduk Institute’s 108 dummy corporations).⁵ Japan’s native religion Shinto also shows its hand, most notably through the depiction of the Evangelions themselves, which Anno consciously designed after the monstrous oni of Japanese legend. All in all, while he may not have intended to portray a particular theological message, it’s clear that Anno put a lot of thought and research into giving Evangelion a suitably mystical appearance.

However, obsessing over the religious imagery in Evangelion obfuscates something far more important: Evangelion isn’t really about religion. Rather, where Evangelion’s thematic depth and complexity most clearly comes into play is psychology and philosophy of the mind.

Neon Genesis Evangelion is often described as a deconstruction of mecha anime. To a large extent that’s true, but it’s deconstruction is specific in outlook, focused on the psychology of its characters in the form of a question: just what kind of people would put the fate of humanity in the hands of adolescent children? And just what would that kind of stress and responsibility do to a child’s mind? In that regard, NGE is in far closer in kinship to Ender’s Game than to its natural predecessors like Macross, Gundam, or Gunbuster.

When the story of Neon Genesis Evangeliom begins, the world has already experienced disaster on an unprecedented scale. 14 years before the show begins, a massive apocalyptic event called the Second Impact devastated the Earth’s climate, precipitated global nuclear war, awakened the monstrous Angels, and resulted in the deaths of half of all humans on the planet. In response, civilization has been restructured and militarized in anticipation of an even worse Third Impact threatened by the Angels. To combat this threat, the secretive organization Nerv assembles biomechanical monsters of their own (the Evangelions) which, as it so happens, can only be piloted by teenagers.⁶

Rei Ayanami, the First Child, believes that her life is expendable

This is the kind of world people like Misato Katsuragi, Gendo Ikari, and Ritsuko Akagi live in and it’s the severity of their situation which ultimately shapes their actions. Although many of the adults, particularly Misato, wish they could let the series’ child protagonists lead a normal life, they know that’s not an option. As a result, the adult characters are driven towards a cold pragmatism that means, no matter how warm or compassionate they may act towards their wards at any given time, they’re still ready to sacrifice them when necessary.

This ruthless approach has its costs, however. The constant pressure to succeed, alongside the emotional whiplash they receive at the hands of the pilots’ supervisors and the repeated trauma they experience in combat results in each pilot’s gradual psychological degradation. Beginning as relatively competent and capable (if slightly dysfunctional) individuals, each pilot eventually succumbs to their trauma and breaks, causing them to isolate themselves from one another and resulting in a breakdown in morale which puts not only themselves but humanity itself at risk.

In keeping with this theme of psychological frailty and the ways in which we as people both intentionally and unintentionally harm those we care about, including those we care about, the series makes numerous allusions to the work of past psychologists and philosophers. Many concepts are mentioned specifically by name, such as the “oral stage,” “separation anxiety,” or the “hedgehog’s dilemma,” while others are alluded to more subtly, such as the Oedipus and Elektra complexes, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, or Lacan’s dichotomy of the constructed and ideal selves.

Hideaki Anno has himself said he researched psychology both before and during the production of Neon Genesis Evangelion and that many of the show’s characters are based upon both these concepts and his own experiences. He has, for instance, described the protagonist Shinji as a reflection of his own conscious self, while the emotionally withdrawn Rei is a manifestation of his unconscious, and the enigmatic Kaworu is his Jungian shadow. Altogether, the works of Freud, Lacan, Schopenhauer, Hegel, Jung, and Sartre have all been identified by staff or critics as influences on the show’s characters and plot.

One of the chief psychological themes in Evangelion is abandonment, particularly by those you love or have been cared for by. Throughout the story—in its past, present, and future—each of the main characters is abandoned by people important to them: their parents, their guardians, their lovers, their friends, etc. Invariably, this abandonment leads to a breakdown in identity and self-confidence, as each character is forced to redefine themselves from within after devoting so much of their identity to how they were perceived by others. Thematically matching to this issue of personal abandonment is humanity’s own abandonment by their unknowable creator eons ago, a detail alluded to occasionally as the story progresses. Like the individual characters then, humanity must learn how to manage and master its own fate when it has no one left to depend upon.

The Hedgehog’s Dilemma

These themes, however, would have little resonance were they irrelevant to the show’s human drama. It is to Neon Genesis Evangelion’s credit that they are not; each of the characters represent the show’s themes in both significant and personal ways. It is quite arguable then that it is the show’s protagonists, however controversial they may be either as individuals or an ensemble, which have truly allowed NGE to endure for decades as an icon of Japanese pop culture.

The most important of Neon Genesis Evangelion’s characters by far is easily Shinji Ikari, the pilot of Evangelion Unit-01 and the son of Gendo Ikari, the enigmatic director of the Evangelion program. At the beginning of the series Shinji is called to Nerv by his father, who abandoned him years earlier following the death of Shinji’s mother. Shinji hopes that this sudden call is for the purpose of reunion, but he is quickly disillusioned when his father reveals to him that he needs Shinji to pilot one of the monstrous Evangelions he’s built—a machine Shinji has hitherto never heard of—and to save humanity from extinction. Brokenhearted by his father’s coldness and terrified of the task he’s been blackmailed into performing, Shinji puts off his own desires and self-identity aside for the sake of pleasing his father and others, becoming the so-called Third Child.

Series protagonist Shinji Ikari, the Third Child

Shinji’s a complicated character and one many find difficult to empathize with. He is self-consciously cowardly and phlegmatic, prone to self-criticism, and afraid of getting close to others for fear that they’ll reject him. At times he thinks seriously about running away from his responsibilities, but whenever he actually does he quickly returns, unable to commit to so blatant an act of rebellion for long. Despite this and despite his own reliance on others to define his value, Shinji does have his virtues: he’s thoughtful, easy to get along with, and proves remarkably skilled at piloting, even if he has no real passion for it.

Shinji’s commanding officer, Misato Katsuragi, is NGE’s most prominent adult character and (according to Hideaki Anno) the series’ deuteragonist.⁸ Loud, goofy, and irreverent, Misato strikes quite a different first impression than Shinji, but despite their outward differences they’re actually quite similar people with comparable issues, merely approaching them in different manners. Like Shinji, Misato feels abandoned by her father, who neglected her and her mother before his death years ago. But despite that Misato still yearns for his affection, manifesting her desires in the form of her relationship with Ryoji Kaji, a coworker and lover she admits resembles her father. And, also like Shinji, Misato fears getting close to other people for fear of being hurt, but whereas Shinji manages his anxiety by avoiding people, Misato does so by acting flippant and flirtatious in public, living lightly and maintaining only “surface level relationships.”

Shinji’s move into Misato’s apartment comes largely at her insistence and Shinji is initially quite uncomfortable with it, a feeling which does not subside when he learns she’s an extremely messy housekeeper and an alcoholic. But despite her irreverent personality, Misato turns out to be a deeply caring person who wants very much for Shinji to be happy and, over the course of the series, she tries to direct the development of Shinji as a good parent would, all the while concerned her own flaws make her an unsuitable guardian. Notably, these moments where the two of them bond are some of the most light-hearted in the series.

Although Shinji is the first pilot the series introduces, he is preceded by two others at Nerv. The first, Rei Ayanami, is arguably Neon Genesis Evangelion’s most popular (and certainly influential) character. Enigmatic and asocial to a degree that goes beyond mere awkwardness, Rei lives alone in a desolate apartment she doesn’t even bother to clean, close to no one but her pseudo-guardian Gendo Ikari. Because of her closeness to his father, who has raised her as his own daughter, Shinji initially sees Rei as a replacement for him. It soon becomes apparent however that Rei’s trust and faith in Gendo go well beyond that of a healthy parent-child dynamic. Obedient to a fault and unconcered for her own well-being, Rei causally throws herself into danger for Gendo and Nerv and comes across as emotionless to those around her.

But beneath Rei’s cold, ultra-stoic exterior beats a heart as capable of joy and sorrow as that of any other. Far from the robotic doll many assume her to be, Rei has a secret yearning for others to understand her and her them and, over the course of the series, slowly opens up to Shinji. But although she desires human contact, she doesn’t really know how to initiate it and she’s terrified of the possibility that there’s something about her that makes her fundamentally unlike other people.

Asuka Langley Soryu, the third of the child protagonists to show up,⁷ strikes about as strong a contrast to Rei as one can imagine. Egotistical, loud-mouthed, and possessed of far more bravado than either Shinji or Rei, Asuka joins the cast about a third of the way through the show, after transferring from Nerv’s facility in Germany. Raised since childhood to be a pilot, Asuka prides herself on her skills and looks with disdain on Shinji’s self-deprecating nature and inability to recognize his own accomplishments. Already a college graduate and convinced she’s as much an adult as anyone, Asuka also proves precociously sexual, pining for both Misato’s lover Kaji and, to a lesser but still significant extent, Shinji himself, whom she frequently teases for attention.

Asuka is like Shinji a controversial character; people often look at Asuka and see one of two sides to her: a selfish jerk who bullies Shinji and Rei or an accomplished young woman whose confidence and inner strength makes her the real hero of the show. The truth, however, is that in many ways she’s both. Asuka really is brave—far braver than Shinji or even Rei, who doesn’t really fear death—and she’s definitely skilled. But she’s also prone to jealousy and vindictiveness, as well as a consciously manifested attitude of not caring for anyone. In many ways, however, her bravado is a cover for own insecurity, built upon the belief that no one really likes or loves her.

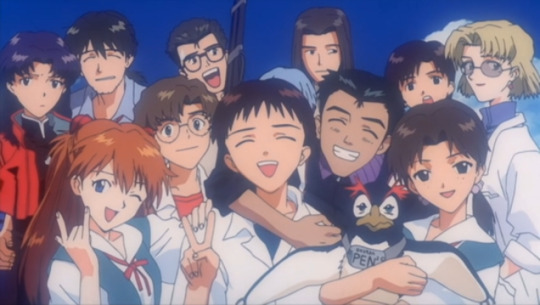

The cast of the original Neon Genesis Evangelion

There’s a lot to admire about NGE’s characters, even with all their flaws and personality disorders. It’s easily got one of the most complex and diverse casts in anime and there has to be something said for the fact that of its four principal characters, three are female, allowing it to easily pass the Bechdel-Wallace Test (which it does). The characters each have their own virtues, which in a more easygoing series could make them quite endearing. Lead protagonist Shinji’s selfless and has a fairly noble streak, though it’s hidden deep beneath his own self-doubt and loathing. The adult Misato’s fairly protective of her young charges, at least insofar as she is allowed to be given the circumstances, and is also quite a bit more capable than many expect. Selfless Rei’s loyalty and discipline easily make her one of the most sympathetic characters in the series, even if she does sometimes come across as alien or inhuman. And there’s little question that the daring Asuka has enough chutzpah for the whole cast.

But it could also be argued that the complexity and harshness of NGE’s characters which ultimately make them work, even if at times they also make the show hard to watch. Shinji, Misato, Rei, and Asuka are not the idealized paragons of humanity you’d expect to find in most television shows aimed at teenagers, but they’re not the imaginings of a bitter misanthrope either. They’re deeply flawed, yes, and when they’re hurt they keep on hurting, but they also keep going and keep trying to find a way to live with others that doesn’t result in pain. It’s this idea, the recognition that people screw up and hurt one another but want to do better, that really enlivens the franchise. For all the reputed darkness of Evangelion’s story, it is in many ways idealistic, always hopeful that it’s characters might find a way to be happy. You don’t have to be broken, it says, even if you are damaged.

And it is that core ethos of qualified hope that elevates Neon Genesis Evangelion from just another mecha anime or even a deconstruction of mecha to something more. Something sublime and, in its own strange way, even inspirational.

The Sickness unto Death

At this point I feel it’s useful to provide some personal background. I first watched Neon Genesis Evangelion when I was in high school, sometime between my third and fourth years. My initial reaction was, I think, largely typical. The first episodes interested me and as the storyline moved forward and became more complex, I became more invested in the show’s events and characters. I even appreciated to some extent the bizarre and abstract final two episodes, though I’d hoped for a more conventional ending. Then, I watched The End of Evangelion, whoch left me shocked and dismayed at its harshness. I still cared about the series, but I felt more ambivalent as a result.

Over the next few years I continued to keep up with the Evangelion fandom to a small extent, checking out the rumors about the new movies and reading some fan fiction online, but I gradually drifted away. None of the fan speculation or fiction really seemed to scratch the same itch the original series had and eventually my interests in anime shifted more towards Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex and Fullmetal Alchemist. Evangelion, as much as I’d enjoyed it before, fell gradually into the background of my life.

And then I entered college.

In my youth, I was generally regarded as a “bright” student, fawned over by teachers and regarded by my peers as either a genius or a “know-it-all,” depending on how much they liked me (or didn’t). As I entered the final years of high school it was clear that I was expected to excel in university. But when I actually began my college career I quickly faltered. Depressed, socially isolated, and exhausted from getting four to six hours of sleep a night, my grades slipped quickly and my social life evaporated. For awhile, I tried to deny my problems and ignore them, believing I could power through without help. Eventually, though, I had no choice but to confront my issues: I was put on academic suspension and my financial assistance was pulled.

I was devastated. I had no idea what to do. I didn’t know how to tell my parents, who I’d let believe I was doing fine. I didn’t know where to go with my life now that I’d failed to live up to the expectations I’d allowed other people to put on me. I didn’t even really know who I was anymore. If I wasn’t a brilliant student and child genius, who was I? In my own eyes I was worthless and contemptible.

Eventually, with the help of my family and friends, as well as staff from the university, I was able to make my way back to daylight. I began to undertake counseling. I went to community college to bring my GPA back up. I started talking more openly with my loved ones about my problems, even though I was worried it would make them think less of me. And I began to be more honest about my flaws and limitations.

A scene from Evangelion 3.0: You Can (Not) Redo, the third Rebuild film

It was also around this time, rather coincidentally, that I began to seriously revisit Evangelion. I was prompted, as much as by anything else, by the release of the new “Rebuild of Evangelion” films. After my brothers and I attended a screening of the second film’s release in early 2011 with several of our friends, the latter (hitherto unfamiliar with Evangelion) expressed interest in catching up with the franchise. Indulging them, my brothers and I rewatched the original TV series. To my surprise, I began to see the series in a new light. Where once I had simply been sympathetic to Shinji, Misato, Rei, and Asuka’s inner turmoil, now I felt deeply empathetic. Where previously the show’s harshness had at times alienated me, now it felt deeply relatable and truthful. And where earlier the TV show’s decision to focus on the internal psyches of its main characters instead of the plot had puzzled me before, now I felt as if I understood it completely. I even began to appreciate the theatrical finale, a film so brutal some regard it (falsely) as Anno’s revenge against fans angry with him for the original ending.

What had changed? Certainly not the show. Rather, it was my perspective. I possessed now of a viewpoint I hadn’t held earlier. I knew now what it was like to be full of contempt for one’s self, to be a defeated shell of a person who felt as though their value was slipping away or was already entirely absent. I knew what it was like to believe I was a failure in every meaningful way. In other words, I’d gained the perspective of a person suffering from depression. The same perspective as that of Evangelion’s principal characters as well as their creator, Hideaki Anno.

It’s hardly secret knowledge that Hideaki Anno was suffering from depression when he first created Neon Genesis Evangelion. The extent of his depression, however, was far graver than is generally recognized. When Anno began work on the project that would become NGE, he had already been suffering from severe depression for at least four years. In a statement released with the first volume of Evangelion’s manga (comic) adaptation Anno described himself as “a broken man... who ran away for four years, one who was simply not dead.” And while the production of NGE had originally been intended to break him out of a rut, the stress only compounded the severity of his condition. By the time of the show’s completion Anno was, by his own later admission, borderline suicidal.

No one’s ever said precisely what drove Anno over the edge publicly, but it’s widely agreed it had much to do with the production of his previous work, Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water. Originally conceived by Anno’s mentor Hayao Miyazaki in the mid-1980s Nadia was eventually handed off to Anno after Gainax made a bid for the project. Far gentler and family-friendly than NGE, the comparative sweetness of Nadia obscured a troubled production that saw animation work outsourced and Anno frequently butting heads with NHK, the series’ broadcaster, over the show’s content and creative direction. Coupled with rumored trouble in Anno’s personal life, the experience proved too much for him, driving him into the deep depression that would haunt him for most of the 1990s.

The roots of Anno’s emotional troubles may go deeper, however. Long regarded by those close to him as a lonely and eccentric oddball, Anno was socially withdrawn as a child, preferring to spend his time watching and recreating scenes from his favorite anime and tokusatsu to interacting with others, a choice he’d later say he regretted. In 1983, due in large part to his social isolation and inactivity at school, he dropped out of university and lived homeless for a time before he was discovered by Miyazaki and employed as an animator for Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. The experience proved vital to his career and soon afterward he and a few friends gathered to form Gainax, their own animation studio. It was during this time that Anno directed Gunbuster alongside working on other projects such as Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise and Grave of the Fireflies. For a time, he seemed happy. But then came Nadia and he withdrew entirely from his work and social life, before reemerging to work on Evangelion.

Anno’s turbulent life and emotional turmoil is reflected in the characters of Evangelion, many of whom enter the story damaged but apparently functional only to completely fall apart later on. Shinji is lonely and dependent when he first appears, but he still manages to form friendships and do what’s required of him. Misato may be an alcoholic with a mess of a home, but Nerv’s trust in her is rewarded time and time again by her effectual planning and coordination of her pilots. Rei’s cold and emotionally withdrawn, but her dutiful selflessness both inspires and attracts others to her. Asuka can be arrogant and reckless, but she’s also intelligent and capable of real kindness towards those she respects. Like Anno in the early days of Gainax, they all seem to be on top of things.

But just when it seems like the team’s getting the hang of things and finding their groove, disaster strikes. Soon, as one crisis mounts on top of another, from near-death experiences to being forced to hurt his friends, everything falls apart. Shinji’s newfound self-confidence shatters and he becomes even more needy than before. Misato’s constructed domestic bliss blows apart just as her own convictions are thrown into question by new revelations about her work. Rei becomes colder and more distant than ever before, withdrawing even from Gendo, the one person she trusts implicitly. And Asuka collapses into a pit of self-loathing despair, savagely lashing out at anyone who gets close to her. It’s ugly, it’s nasty, and it’s real.

Shinji admits to his feelings of worthlessness to Misato Katsuragi, his guardian and confidante, in The End of Evangelion

This cycle of crash, despair, and recovery is not unusual for suffers of depression. Contrary to what is often thought, depression is not really something you have at one point in your life and then “get over;” it’s something that can shadow you your entire life, kept in check by momentary pleasures and good times but always threatening to surge and overwhelm you when things go awry, sending you into a spiral of self-hate and abnegation that can last for weeks, months, or even years. Friends and family help keep it in check, as does therapy and pharmaceuticals, but it never goes away completely. The only thing you can do is recognize the symptoms and do your best to confront them. You have to keep going. You can’t let your fears drive you to abandon the world. You must not, in other words, run away.

And really that’s what the characters’ struggles in Evangelion come down to: facing reality and acknowledging their flaws while also recognizing their own potential to overcome them and the painful struggle for acceptance we all, on some level, endure. The first instinct of every character in the series is to run away from their problems, to obscure them with outwardly derived duties, relationships, or purposes. Shinji and Rei both look to Gendo, Misato to her job, and Asuka to her pride as an Eva pilot, but all of them are running away and, as a consequence, are unprepared to deal with reality when it hits them flat in the face.

Or are they?

As Long As You Try to Continue to Live

It’s worth noting that when Anno created Neon Genesis Evangelion he didn’t initially set out to create a dark and cynical deconstruction of mecha anime. When asked what initially gave him the impetus to create NGE, Anno has said repeatedly that he originally meant to make a show more in the spirit of Gundam or Space Battleship Yamato, two of his favorite TV shows from his youth, but without the shackles inherent to sponsorship by a toy company, as was common practice for anime at the time. “I made Evangelion to make me happy and to make anime lovers happy,” he said in a 1996 interview, “in trying to bring together the broadest audience possible.”

But as pre-production on the series progressed (and his emotional state regressed) Anno became further disenchanted at the state of anime, concerned that fans were turning to it as a way to escape reality as he himself felt compelled to. “I wonder if a person over the age of twenty who likes robot anime is really happy,” he stated in an article for Newtype half a year before the series aired. This change in perspective, coupled with his resurgent depression, caused Anno to shift focus as he became more and more concerned with the characters’ emotional development, hoping that by the end of the series’ narrative “the heroes would change,” breaking away from their regressed emotional state and achieving the same emotional well-being and self-dependence Anno still sought for himself and which he felt his audience needed as well.

It’s this perspective of Anno’s—that anime otaku were and are caught in a kind of prolonged childhood—which has led to the impression that Anno hates otaku and believes their lives to be worthless. But the truth is that Anno’s thoughts on the subject are quite a bit subtler and more reflective than many give him credit for. Far from hating otaku, Anno counts himself among them and feels defensive whenever they’re derided by others. The issue, he thinks, is less that otaku are permanently stunted and more that they’re afraid or reluctant to open themselves to new experiences:

“I feel that otaku have already become common to all countries. In Europe, in Korea, in Taiwan, in Hong Kong, in America, otaku really do not change. I think that this is amazing. I say critical things towards otaku, but I don’t reject them. I only say that we should take a step back and be self-conscious about these things. I think it’s perfectly fine so long as you act with an awareness of what you are doing, self-conscious and cognizant of the current situation. I’m just not sure it’s a good thing to reach the point where you cut yourself off from society. I don’t understand the greatness of society, either. So I have no intention of going so far as to call for people to give up otaku-like things and become more suited to society. Only, I think there are many other interesting things in the world, and we don’t have to reject them.”

Despite everything, the characters still care for and want to see one another happy

And that’s what I mean by Evangelion’s subtle, qualified idealism. Despite Anno’s frequent cynicism and troubled state of mind during the production of the series, it’s clear that at heart he’s a person who believes people can change and improve themselves. He’s someone who believes that, even in the worst or most desperate of situations, people can find happiness if they’re open to it. “As long as you try to continue to live,” one character states in The End of Evangelion, “any place can be a heaven… there’s a chance to become happy everywhere.”

It would certainly be easy to define the characters of Evangelion by their failures and—given the magnitude of their failures—it’s understandable why many do. After all, much of the series’ narrative is caught up (as I noted earlier) in deconstructing the kind of scenario typical of mecha shows and examing what really would happen if teenagers were put in charge of the world’s salvation. As such, as in other deconstructionist narratives (such as the Battlestar Galactica reboot or Watchmen), the characters screw up about at least as often as they succeed.