#entropicalislands

Text

from Oscillons, by Ben F. Laposky, 1952-56

Electronic Abstractions: A New Approach to Design

Ben. F. Laposky, 1953

Are.na>

0 notes

Text

Integrated Information Theory Φ by Giulio Tononi

Integrated Information Theory (IIT) is a framework for understanding consciousness that has been developed by neuroscientist Giulio Tononi and further explored by collaborators such as Melanie Boly, Marcello Massimini, and Christof Koch. The theory proposes a quantitative measure, denoted as Φ (phi), which is intended to indicate the level of integrated information within a system—a measure that, according to IIT, correlates directly with consciousness.

Key Concepts of Integrated Information Theory

Integrated Information (Φ):

IIT posits that consciousness arises from the ability of a system to integrate information in a way that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. This integration is measured by Φ, which quantifies how much more information is generated by the interconnected system as a whole compared to what would be generated by its individual parts working independently.

Intrinsic Cause-Effect Power:

The theory argues that the physical substrate of consciousness must possess a high degree of intrinsic cause-effect power. This means that the system must be able to determine its own state through a complex of internal interactions that cannot be reduced merely to the behavior of its components.

Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for Consciousness:

IIT proposes that a high Φ is both necessary and sufficient for consciousness. This suggests that any system with a sufficiently high Φ, regardless of its makeup (biological or artificial), should possess consciousness.

Counterintuitive Predictions:

IIT leads to some predictions that may seem counterintuitive. For example, a system can have high Φ and thus be considered conscious even if it does not interact with its environment or display outward behavior that typically accompanies consciousness in humans and other animals.

Applications and Implications

Assessment of Consciousness: IIT provides a theoretical basis for developing tools to assess consciousness, particularly in cases where traditional behavioral indicators are absent, such as in non-communicative patients or potentially in machines.

Philosophical and Ethical Questions: The theory raises significant questions about the nature of consciousness, the ethical treatment of systems (biological or artificial) that might have high Φ, and the understanding of consciousness in medical and legal contexts.

Criticisms and Challenges

Disconnection from Behavior:

One of the main criticisms of IIT is that it divorces consciousness from observable behavior. Traditional views often link consciousness closely with behavioral responses, and IIT's framework challenges these assumptions by suggesting that consciousness can exist even in isolated systems that do not interact with their surroundings.

Measurability of Φ:

Calculating Φ in complex systems is technically challenging and computationally intensive. This raises practical questions about the feasibility of applying IIT in real-world scenarios.

Philosophical Underpinnings:

The assumption that consciousness can be fully explained as a form of information integration is philosophically controversial and not universally accepted.

***

Abstract

In this Opinion article, we discuss how integrated information theory accounts for several aspects of the relationship between consciousness and the brain. Integrated information theory starts from the essential properties of phenomenal experience, from which it derives the requirements for the physical substrate of consciousness. It argues that the physical substrate of consciousness must be a maximum of intrinsic cause–effect power and provides a means to determine, in principle, the quality and quantity of experience. The theory leads to some counterintuitive predictions and can be used to develop new tools for assessing consciousness in non-communicative patients.

Article >

***

"The neuroscientist Giulio Tononi has purported to supply just such a measure, named Φ, within the rubric of so-called ‘integrated information theory’.

Here, Φ describes the extent to which a system is, in a specific information-theoretic sense, more than the sum of its parts.

For Tononi, consciousness is Φ in much the same sense that water is H2O.

So, integrated information theory claims to supply both necessary and sufficient conditions for the presence of consciousness in any given dynamical system.

The chief difficulty with this approach is that it divorces consciousness from behaviour.

A completely self-contained system can have high Φ despite having no interactions with anything outside itself.

Yet our everyday concept of consciousness is inherently bound up with behaviour. If you remark to me that someone was or was not aware of something (an oncoming car, say, or a friend passing in the corridor) it gives me certain expectations about their behaviour (they will or won’t brake, they will or won’t say hello).

I might make similar remarks to you about what I was aware of in order to account for my own behaviour. ‘I can hardly tell the difference between those two colours’; ‘I’m trying to work out that sum in my head, but it’s too hard’; ‘I’ve just remembered what she said’; ‘It doesn’t hurt as much now’ – all these sentences help to explain my behaviour to fellow speakers of my language and play a role in our everyday social activity.

They help us keep each other informed about what we have done in the past, are doing right now or are likely to do in the future. Problematic — What if I say to you, there is no past, there is no future ? Everything is in exist in me alpha&omega.

It’s only when we do philosophy that we start to speak of consciousness, experience and sensation in terms of private subjectivity.

0 notes

Text

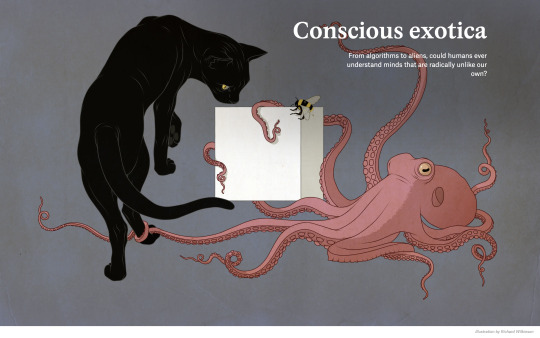

Conscious exotica

From algorithms to aliens, could humans ever understand minds that are radically unlike our own?

Read PDF >

In 1984, the philosopher Aaron Sloman invited scholars to describe ‘the space of possible minds’. Sloman’s phrase alludes to the fact that human minds, in all their variety, are not the only sorts of minds. There are, for example, the minds of other animals, such as chimpanzees, crows and octopuses. But the space of possibilities must also include the minds of life-forms that have evolved elsewhere in the Universe, minds that could be very different from any product of terrestrial biology. The map of possibilities includes such theoretical creatures even if we are alone in the Cosmos, just as it also includes life-forms that could have evolved on Earth under different conditions.

We must also consider the possibility of artificial intelligence (AI). Let’s say that intelligence ‘measures an agent’s general ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments’, following the definition adopted by the computer scientists Shane Legg and Marcus Hutter. By this definition, no artefact exists today that has anything approaching human-level intelligence. While there are computer programs that can out-perform humans in highly demanding yet specialised intellectual domains, such as playing the game of Go, no computer or robot today can match the generality of human intelligence.

But it is artefacts possessing general intelligence – whether rat-level, human-level or beyond – that we are most interested in, because they are candidates for membership of the space of possible minds. Indeed, because the potential for variation in such artefacts far outstrips the potential for variation in naturally evolved intelligence, the non-natural variants might occupy the majority of that space. Some of these artefacts are likely to be very strange, examples of what we might call ‘conscious exotica’.

In what follows I attempt to meet Sloman’s challenge by describing the structure of the space of possible minds, in two dimensions: the capacity for consciousness and the human-likeness of behaviour. Implicit in this mapping seems to be the possibility of forms of consciousness so alien that we would not recognise them. Yet I am also concerned, following Ludwig Wittgenstein, to reject the dualistic idea that there is an impenetrable realm of subjective experience that forms a distinct portion of reality. I prefer the notion that ‘nothing is hidden’, metaphysically speaking. The difficulty here is that accepting the possibility of radically inscrutable consciousness seemingly readmits the dualistic proposition that consciousness is not, so to speak, ‘open to view’, but inherently private. I try to show how we might avoid that troubling outcome.

***

Thomas Nagel’s celebrated treatment of the (modestly) exotic subjectivity of a bat is a good place to start. Nagel wonders what it is like to be a bat, and laments that ‘if I try to imagine this, I am restricted to the resources of my own mind, and those resources are inadequate to the task’. A corollary of Nagel’s position is that certain kinds of facts – namely facts that are tied to a very different subjective point of view – are inaccessible to our human minds. This supports the dualist’s claim that no account of reality could be complete if it comprised only objective facts and omitted the subjective. Yet I think the dualistic urge to cleave reality in this way is to be resisted. So, if we accept Nagel’s reasoning, conscious exotica present a challenge.

But bats are not the real problem, as I see it. The moderately exotic inner lives of non-human animals present a challenge to Nagel only because he accords ontological status to an everyday indexical distinction. I cannot be both here and there. But this platitude does not entail the existence of facts that are irreducibly tied to a particular position in space. Similarly, I cannot be both a human and a bat. But this does not entail the existence of phenomenological facts that are irreducibly tied to a particular subjective point of view. We should not be fooled by the presence of the word ‘know’ into seeing the sentence ‘as a human, I cannot know what it’s like to be a bat’ as expressing anything more philosophically puzzling than the sentence ‘I am a human, not a bat.’ We can always speculate about what it might be like to be a bat, using our imaginations to extend our own experience (as Nagel does). In doing so, we might remark on the limitations of the exercise. The mistake is to conclude, with Nagel, that there must be facts of the matter here, certain subjective ‘truths’, that elude our powers of collective investigation.

To explore the space of possible minds is to entertain the possibility of beings far more exotic than any terrestrial species

In this, I take my cue from the later Wittgenstein of The Philosophical Investigations (1953). The principle that underlies Wittgenstein’s rejection of private language – a language with words for sensations that only one person in the world could understand – is that we can talk only about what lies before us, what is public, what is open to collective view. As for anything else, well, ‘a nothing would serve as well as a something about which nothing can be said’. A word that referred to a private, inner sensation would have no useful function in our language. Of course, things can be hidden in a practical sense, like a ball beneath a magician’s cup, or a star that is outside our light cone. But nothing is beyond reach metaphysically speaking. When it comes to the inner lives of others, there is always more to be revealed – by interacting with them, by observing them, by studying how they work – but it makes no sense to speak as if there were something over and above what can ever be revealed.

Following this train of thought, we should not impute unknowable subjectivity to other people (however strange), to bats or to octopuses, nor indeed to extra-terrestrials or to artificial intelligences. But here is the real problem, namely radically exotic forms of consciousness. Nagel reasonably assumes that ‘we all believe bats have experience’; we might not know what it is like to be a bat, yet we presume it is like something. But to explore the space of possible minds is to entertain the possibility of beings far more exotic than any terrestrial species. Could the space of possible minds include beings so inscrutable that we could not tell whether they had conscious experiences at all? To deny this possibility smacks of biocentrism. Yet to accept it is to flirt once more with the dualistic thought that there is a hidden order of subjective facts. In contrast to the question of what it is like to be an X, surely (we are tempted to say) there is a fact of the matter when it comes to the question of whether it is like anything at all to be an X. Either a being has conscious experience or it does not, regardless of whether we can tell.

***

Consider the following thought experiment. Suppose I turn up to the lab one morning to discover that a white box has been delivered containing an immensely complex dynamical system whose workings are entirely open to view. Perhaps it is the gift of a visiting extraterrestrial, or the unwanted product of some rival AI lab that has let its evolutionary algorithms run amok and is unsure what to do with the results. Suppose I have to decide whether or not to destroy the box. How can I know whether that would be a morally acceptable action? Is there any method or procedure by means of which I could determine whether or not consciousness was, in some sense, present in the box?

One way to meet this challenge would be to devise an objective measure of consciousness, a mathematical function that, given any physical description, returns a number that quantifies the consciousness of that system. The neuroscientist Giulio Tononi has purported to supply just such a measure, named Φ, within the rubric of so-called ‘integrated information theory’. Here, Φ describes the extent to which a system is, in a specific information-theoretic sense, more than the sum of its parts. For Tononi, consciousness is Φ in much the same sense that water is H2O. So, integrated information theory claims to supply both necessary and sufficient conditions for the presence of consciousness in any given dynamical system.

The chief difficulty with this approach is that it divorces consciousness from behaviour. A completely self-contained system can have high Φ despite having no interactions with anything outside itself. Yet our everyday concept of consciousness is inherently bound up with behaviour. If you remark to me that someone was or was not aware of something (an oncoming car, say, or a friend passing in the corridor) it gives me certain expectations about their behaviour (they will or won’t brake, they will or won’t say hello). I might make similar remarks to you about what I was aware of in order to account for my own behaviour. ‘I can hardly tell the difference between those two colours’; ‘I’m trying to work out that sum in my head, but it’s too hard’; ‘I’ve just remembered what she said’; ‘It doesn’t hurt as much now’ – all these sentences help to explain my behaviour to fellow speakers of my language and play a role in our everyday social activity. They help us keep each other informed about what we have done in the past, are doing right now or are likely to do in the future.

It’s only when we do philosophy that we start to speak of consciousness, experience and sensation in terms of private subjectivity. This is the path to the hard problem/easy problem distinction set out by David Chalmers, to a metaphysically weighty division between inner and outer – in short, to a form of dualism in which subjective experience is an ontologically distinct feature of reality. Wittgenstein provides an antidote to this way of thinking in his remarks on private language, whose centrepiece is an argument to the effect that, insofar as we can talk about our experiences, they must have an outward, public manifestation. For Wittgenstein, ‘only of a living human being and what resembles (behaves like) a living human being can one say: it has sensations, it sees … it is conscious or unconscious’.

Through Wittgenstein, we arrive at the following precept: only against a backdrop of purposeful behaviour do we speak of consciousness. By these lights, in order to establish the presence of consciousness, it would not be sufficient to discover that a system, such as the white box in our thought experiment, had high Φ. We would need to discern purpose in its behaviour. For this to happen, we would have to see the system as embedded in an environment. We would need to see the environment as acting on the system, and the system as acting on the environment for its own ends. If the ‘system’ in question was an animal, then we already inhabit the same, familiar environment, notwithstanding that the environment affords different things to different creatures. But to discern purposeful behaviour in an unfamiliar system (or creature or being), we might need to engineer an encounter with it.

Even in familiar instances, this business of engineering an encounter can be tricky. For example, in 2006 the neuroscientist Adrian Owen and his colleagues managed to establish a simple form of communication with vegetative-state patients using an fMRI scanner. The patients were asked to imagine two different scenarios that are known to elicit distinct fMRI signatures in healthy individuals: walking through a house and playing tennis. A subset of vegetative-state patients generated appropriate fMRI signatures in response to the relevant verbal instruction, indicating that they could understand the instruction, had formed the intention to respond to it, and were able to exercise their imagination. This must count as ‘engineering an encounter’ with the patient, especially when their behaviour is interpreted against the backdrop of the many years of normal activity the patient displayed when healthy.

We don’t weigh up the evidence to conclude that our friends are probably conscious creatures. We simply see them that way, and treat them accordingly

Once we have discerned purposeful behaviour in our object of study, we can begin to observe and (hopefully) to interact with it. As a result of these observations and interactions, we might decide that consciousness is present. Or, to put things differently, we might adopt the sort of attitude towards it that we normally reserve for fellow conscious creatures.

The difference between these two forms of expression is worth dwelling on. Implicit in the first formulation is the assumption that there is a fact of the matter. Either consciousness is present in the object before us or it is not, and the truth can be revealed by a scientific sort of investigation that combines the empirical and the rational. The second formulation owes its wording to Wittgenstein. Musing on the skeptical thought that a friend could be a mere automaton – a phenomenological zombie, as we might say today – Wittgenstein notes that he is not of the opinion that his friend has a soul. Rather, ‘my attitude towards him is an attitude towards a soul’. (For ‘has a soul’ we can read something like ‘is conscious and capable of joy and suffering’.) The point here is that, in everyday life, we do not weigh up the evidence and conclude, on balance, that our friends and loved ones are probably conscious creatures like ourselves. The matter runs far deeper than that. We simply see them that way, and treat them accordingly. Doubt plays no part in our attitude towards them.

How do these Wittgensteinian sensibilities play out in the case of beings more exotic than humans or other animals? Now we can reformulate the white box problem of whether there is a method that can determine if consciousness, in some sense, is present in the box. Instead, we might ask: under what circumstances would we adopt towards this box, or any part of it, the sort attitude we normally reserve for a fellow conscious creature?

***

et’s begin with a modestly exotic hypothetical case, a humanoid robot with human-level artificial intelligence: the robot Ava from the film Ex Machina (2015), written and directed by Alex Garland.

In Ex Machina, the programmer Caleb is taken to the remote retreat of his boss, the reclusive genius and tech billionaire Nathan. He is initially told he is to be the human component in a Turing Test, with Ava as the subject. After his first meeting with Ava, Caleb remarks to Nathan that in a real Turing Test the subject should be hidden from the tester, whereas Caleb knows from the outset that Ava is a robot. Nathan retorts that: ‘The real test is to show you she is a robot. Then see if you still feel she has consciousness.’ (We might call this the ‘Garland Test’.) As the film progresses and Caleb has more opportunities to observe and interact with Ava, he ceases to see her as a ‘mere machine’. He begins to sympathise with her plight, imprisoned by Nathan and faced with the possibility of ‘termination’ if she fails his test. It’s clear by the end of the film that Caleb’s attitude towards Ava has evolved into the sort we normally reserve for a fellow conscious creature.

The arc of Ava and Caleb’s story illustrates the Wittgenstein-inspired approach to consciousness. Caleb arrives at this attitude not by carrying out a scientific investigation of the internal workings of Ava’s brain but by watching her and talking to her. His stance goes deeper than any mere opinion. In the end, he acts decisively on her behalf and at great risk to himself. I do not wish to imply that scientific investigation should not influence the way we come to see another being, especially in more exotic cases. The point is that the study of a mechanism can only complement observation and interaction, not substitute for it. How else could we truly come to see another conscious being as such, other than by inhabiting its world and encountering it for ourselves?

If something is built very differently to us, then however human-like its behaviour, its consciousness might be very different to ours

The situation is seemingly made simpler for Caleb because Ava is only a moderately exotic case. Her behaviour is very human-like, and she has a humanoid form (indeed, a female humanoid form that he finds attractive). But the fictional Ava also illustrates how tricky even seemingly straightforward cases can be. In the published script, there is a direction for the last scene of the film that didn’t make the final cut. It reads: ‘Facial recognition vectors flutter around the pilot’s face. And when he opens his mouth to speak, we don’t hear words. We hear pulses of monotone noise. Low pitch. Speech as pure pattern recognition. This is how Ava sees us. And hears us. It feels completely alien.’ This direction brings out the ambiguity that lies at the heart of the film. Our inclination, as viewers, is to see Ava as a conscious creature capable of suffering – as Caleb sees her. Yet it is tempting to wonder whether Caleb is being fooled, whether Ava might not be conscious after all, or at least not in any familiar sense.

This is a seductive line of thinking. But it should be entertained with extreme caution. It is a truism in computer science that specifying how a system behaves does not determine how that behaviour need be implemented in practice. In reality, human-level artificial intelligence exhibiting human-like behaviour might be instantiated in a number of different ways. It might not be necessary to copy the architecture of the biological brain. On the other hand, perhaps consciousness does depend on implementation. If a creature’s brain is like ours, then there are grounds to suppose that its consciousness, its inner life, is also like ours. Or so the thought goes. But if something is built very differently to us, with a different architecture realised in a different substrate, then however human-like its behaviour, its consciousness might be very different to ours. Perhaps it would be a phenomenological zombie, with no consciousness at all.

The trouble with this thought is the pull it exerts towards the sort of dualistic metaphysical picture we are trying to dispense with. Surely, we cry, there must be a fact of the matter here? Either the AI in question is conscious in the sense you and I are conscious, or it is not. Yet seemingly we can never know for sure which it is. It is a small step from here to the dualistic intuition that a private and subjective world of inner experience exists separately from the public and objective world of physical objects. But there is no need to yield to this dualistic intuition. Neither is there any need to deny it. It is enough to note that, in difficult cases, it is always possible to find out more about an object of study – to observe its behaviour under a wider set of circumstances, to interact with it in new ways, to investigate its workings more thoroughly. As we find out more, the way we treat it and talk about it will change, and in this way we will converge on the appropriate attitude to take towards it. Perhaps Caleb’s attitude to Ava would have changed if he’d had more time to interact with her, to find out what really made her tick. Or perhaps not.

***

0 notes

Text

To be human is to refuse to accept the given as given.

Stephen Duncombe, Dream: Re-imaging Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy (New York: The New Press, 2007), 182.

1 note

·

View note

Text

————

In the book Object-Oriented Ontology by Graham Harman, alongside his explaniation to the core of that phylosophy, openly thesing and mocking the String theory, which assupt as best game in town.

A candide for to be theory of everything, but still lack of so many things, like the exaptence the forces of sensual objects.

Nearly the entire planet spent its days in the tedium of thinking itself a part of a mere menagerie, bound to live within the perfect celestial omens drawn out for them by the godfathers, in a monotheistic universe, until Galileo made statements that confused everyone's minds.

We are still searching for that theory of everything. Searching for the mystery of connection, from the day we arrived, through ancient mythologies to today's daily horoscopes.

Brief look at our vision on universal logic, historic of the space, four false assuption of the super-string theory from (OOO) ;

(revised, for orginal pdf)

In recent decades, few intellectual topics have captured the public imagination like the search for a so-called ‘theory of everything’ in physics.

Brian Greene of Columbia University, who views the currently popular ‘string theory’ as the best existing candidate for a theory explaining the composition of matter and the structure of the cosmos.

The search for unifications in physics has already given humanity some of its most heroic moments.

In the early 1600s, Galileo established the falsity of the ancient view that there is one kind of physics for the eternal bodies in the sky and a completely different kind for the corrupt and decaying things down here on the earth; instead, he showed that one physics governs every portion of the universe.

One of the first and most illustrious examples of the prophetic power of science is reported by Galileo Galilei in his Sidereus Nuncius:

I feel sure that the surface of the Moon is not perfectly smooth, free from inequalities and exactly spherical, as a large school of philosophers considers with regard to the Moon and the other heavenly bodies, but that, on the contrary, it is full of inequalities, uneven, full of hollows and protuberances, just like the surface of the earth itself, which is varied everywhere by lofty mountains and deep valleys.4

At the time this was written, the dominant Aristotelian doctrine taught that the cosmos, along with all the elements that composed it, was perfectly spherical, and that no imperfection was allowed to exist outside of the earth.

Gazing through his telescope, Galileo was struck by a blasphemous revelation: that the moon, and by extension the entire universe, was irremediably dirty and subject to the same processes of degradation and dissolution that we experience in our world.

The apparently innocuous words of his statement, supported by the reasonable argument of scientific observation, hide an actual, gruesome deicide; if the universe is not perfect and eternal, how could God be?

As we now know, the moon’s surface was disfigured by asteroids—celestial omens of death whose distorted, eccentric trajectories escape the comprehension of spherical cosmology.

Interestingly, Galileo somehow expiated his blasphemy by opening the way to the formulation of the principle of the conservation of energy—the first principle of thermodynamics—through his experiments on motion.

The spherical nature of the universe was somehow preserved in the symmetry of the laws of mechanical motion, which imply the total reversibility of all dynamic processes and thus the nonexistence of time as a material drive toward degradation.

This paved the way for the even more fateful unification announced in Sir Isaac Newton’s Principia in 1687. In this masterpiece of the history of science, Newton demonstrated that the movement of celestial bodies and the falling of objects to the ground are governed by one and the same force: gravity, as everyone calls it today.

In the 1860s, James Clerk Maxwell was unify the previously separate forces of electricity and magnetism, and established further that light and electromagnetism travel at the same speed, strongly suggesting that light is simply another manifestation of the same force.

From this consideration it obviously follows that the ultimate prophecy of doom channelled by science is the second principle of thermodynamics in its statistical-mechanical interpretation, as understood by Ludwig Boltzmann:

After this confession you will take it with more tolerance if I am so bold as to claim your attention for a quite trifling and narrowly circumscribed question.

[...] The second law proclaims a steady degradation of energy until all tensions that might still perform work and all visible motions in the universe would have to cease. All attempts at saving the universe from this thermal death have been unsuccessful, and to avoid raising hopes I cannot fulfil, let me say at once that I too shall here refrain from making such attempts. (5)

The ‘narrowly circumscribed question’ of condemning the entire cosmos to irremediable heat death breaks with any surviving hope that the universe may be, in any capacity, spherical, reversible, or eternal.

Boltzmann was a meticulous scientist and a convinced upholder of the inherent boundaries of science and human knowledge; but despite his understandable caution in approaching the subject of his own ground-breaking discoveries, the proof of his H-theorem, containing a probabilistic argument in support of the second principle of thermodynamics, is not merely a speculation on the behaviour of an ideal gas of non-interacting particles, but rather the elaborate conjuration of an eldritch aberration.

As we diligently follow the intricate steps of this twisted ritual, summoning functions and variables and transmuting them through the arcane operations of calculus, we finally reach the Quod Erat Demonstrandum, manifesting the apocalyptic truth of the death of the universe and unleashing it into reality. There is minimal need of scientific understanding to operate the conjuring machine of thermodynamics; it just works—until it works no more.

-

By the 1970s four forces of nature had been recognized: gravity, electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force (which holds atoms together) and the weak nuclear force (which governs radioactive decay).

The 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics went jointly to the physicists Sheldon Lee Glashow, Abdus Salam and Steven Weinberg for their unified theory of the ‘electroweak’ force, while the strong force was accounted for at roughly the same time by QCD, or quantum chromodynamics.

By the mid-1970s, physics had its Standard Model of Particle Physics, which was more or less completed in 2012 by the apparent discovery of the Higgs boson at CERN in Geneva.

In the early twentieth century, quantum theory unified various phenomena of heat, light and atomic motion by explaining them as occurring through discrete jumps rather than continuous increase or decrease.

Among the remaining problems with the Standard Model is that it does not unify gravity with the electromagnetic, strong and weak forces. The pursuit of a workable theory of ‘quantum gravity’ continues to this day, and along with the discovery by astronomers of the still inexplicable dark matter and dark energy, the search for quantum gravity is one of the most likely triggers of the next revolution in physics.

***

After Graham wrote those,

little note about the discovery of black star.

NEMESIS or THE BLACK SUN

Because You love cremation grounds

I have made my heart one

so that You

Black Goddess of the Burning Grounds can always dance there.

No desires are left, Mā, on the pyre

for the fire burns in my heart,

and I have covered everything with its ash to prepare for Your coming.

via: R.F. McDermott, Singing to the Goddess: Poems to Kālī and Umā from Bengal (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 74–75.

***

Nonetheless, no matter how carefully science insists on tracing the limits of its own understanding, barricading itself behind walls of axioms and boundary conditions, it inevitably becomes an oracle, a spiritual medium, opening a laceration onto a radical Outside and summoning an invasion of voices of long-lost demons into our world, not unlike a cursed Cassandra who refuses to surrender to her own prophetic utterances.

The topic of unified theories is so exciting that physicists have created a small industry of readable popular books on the theme, with Greene’s The Elegant Universe one of the most prominent among them.

Maybe we shoulld agree on Graham’s phases:

I certainly agree with Greene that ‘we should not rest until we have a theory whose range of applicability is limitless’. My point of disagreement will sound surprising in the current intellectual climate: I do not agree that physics, or even natural science more generally, is the right place to find such a unified theory. In my view, the ‘theory whose range of applicability is limitless’ can only be found in philosophy, and especially in the type of philosophy called Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO).

Though the rapid advance of modern physics has been one of the most reassuring chapters of human history, I see it as a field that excludes far too much to give us a theory of everything.

Assumptions that graham found wrong in String Theory.

Claim that physics (and string theory in particular) has limitless applicability.

String theory is not the only candidate for a ‘theory of everything’, but it remains the most popular, and for many the most promising.

The theory has been around in some form since the 1960s, but became an especially hot topic two decades later.

String theory postulates that matter is composed of vibrating one-dimensional strings twisting through ten dimensions, rather than the four dimensions of space–time that Einsteinian physics accepts. In so-called ‘ M-theory’, Edward Witten’s 1995 modification of the string landscape, the total number of dimensions was expanded to eleven.

Numerous beautiful mathematical and physical results can be derived from the theory, including a possible account of the everelusive quantum gravity, meaning a theory of gravity that can be explained in terms of quantum mechanics just as the electromagnetic, strong and weak forces already have been.

Nonetheless, a backlash against string theory began in the twenty-first century, as can be seen in the widely read critical books by physicists Lee Smolin and Richard Woit.

Perhaps the most frequent accusation against string theory by sceptics is that it cannot be experimentally tested, and is therefore said to be little more than a mathematical exercise of no direct relevance to physics.

Another problem is that so many thousands of different string theories are mathematically possible that there is no reason to choose one in particular, except on the shaky basis that we must obviously choose the theory that fits the structure of the universe we know: for otherwise we would not be here today to have debates about it.

This line of reasoning is known as the ‘anthropic principle’, viewed by many scientists with contempt but by others as a pivotal intellectual tool. Lastly, Smolin in particular is alarmed by the near-monopoly of string theory in the leading graduate courses in physics, which for him means that the entire profession has put all its eggs in a single, experimentally baseless basket.

String theory would have become textbook science, learned by students everywhere as a basic fact about our world, much like Einstein’s theory of gravity or the periodic table of chemical elements. My claim is that even under this optimal scenario of maximum scientific triumph, string theory would still not be a ‘theory of everything’. To see why, let’s examine what I take to be the four false assumptions behind statements that string theory’s range of applicability is limitless.

First False Assumption: everything that exists must be physical.

A successful string theory would sum up everything we know about the structure and behaviour of physical matter. But this makes it a ‘theory of everything’ only on the condi- tion that everything is physical.

Of course, many people do not see it this way.

Religion is a far weaker force in Europe than it used to be, though it remains significantly stronger in the United States, and very much stronger in other parts of the world. Among adherents of all religions, belief in immaterial gods and souls is nearly universal. Many other people around the world, including a number of unreligious ones, still believe in ghosts and spirits. In almost every country, a number of buildings stand out for their reputation as being especially haunted.

In more refined circles we find Jungian psychology, which affirms the existence of unconscious and immaterial archetypes shared collectively by all human beings.

By hypothesis, a mainstream physicist will dismiss all such ideas as unscientific rubbish; A ‘theory of everything’, does not mean a theory that includes all of the nonsense that gullible people think is real, but only a theory of what rational and scientifically minded people know to be real: the physical–material universe. (?)

Though I for one am not particularly convinced by Jungian psychology, I do read Jung from time to time and find that he improves my imagination.

And I would certainly hate to live in a world where Jungian societies were liquidated by the Rationality Police or demoralized by general public mockery.

But let’s suppose we agree with the scepticism of anti-spirutual stories, and join the crowd that disbelief about any gods, souls, ghosts, spirits, unconscious archetypes or other supposed non-material entities. Even if we were to walk this far down in that the path, and even under the supposition that string theory were confirmed by rock-solid evidence,

I would still not agree with her that this meritorious theory could count as a ‘theory of everything’. For we can think of plenty of things that are not physical but which are almost certainly real.

For one thing, material objects always exist somewhere, but in the case of the VOC it is not at all clear where that place of existence would be.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) challenges the notion of being a material object, as material objects have a specific location, which the VOC lacked. The VOC wasn't confined to its Amsterdam headquarters, as its operations were primarily in Southeast Asia, governed independently by a Governor-General without needing to consult Dutch shareholders. Also, its Asian capital, Batavia (now Jakarta), housed only a fraction of its resources and employees. The VOC's regulations applied across its territories, further complicating its physical location. Moreover, the VOC existed from 1602 to 1795, outliving any individual or ship associated with it, thus defying the characteristics of a material thing like a quark, electron, or vibrating string.

There is an old philosophical paradox known as the Ship of Theseus, which poses the problem of whether the ship remains the same even when we gradually or suddenly replace each of its boards with a new one – especially if we assemble the old boards together nearby as a rival vessel to the new ship. Without going further into this paradox I wish to emphasize what I take to be a chief lesson of the VOC case study:

the irreducibility of larger objects to the sum total of their material compo- nents. The Dutch East India Company was not just a collec- tion of atoms and strings at various locations in space–time, but to a large extent was able to survive the motion and dis- appearance of these tiny elements while making use of others.

Second False Assumption: everything that exists must be basic and simple.

Are we missing the point ? we have missed the point.

For while it may be true that the VOC or the Ship of Theseus can survive despite the turnover of their material pieces, they certainly cannot exist without any material pieces at all. If over time the VOC only lost atoms and never gained any, there would finally come a point where its various ships, cargoes and officers would crumble to dust and the VOC would cease to exist.

Maybe theory never meant to tell us there cannot be higher-order objects that seem to endure despite massive turnover in their material components. But such objects must always be made of some physical matter, even if it is relatively unimportant whether one hydrogen atom or another happens to be found in the brain of the VOC’s Governor-General.

The fallacy that the philosopher Sam Coleman has termed ‘smallism’, as if the real ele- ments in any situation were the tiniest components to which everything can be broken down.5 The mid-and large-sized objects that surround us (from cups, tables and flowers to skyscrapers and elephants) seem to have independent fea- tures of their own, but according to thheory these larger objects ultimately receive all of their properties from those of their components; after all, without these small components the larger objects could never exist.

What this argument misses is the phenomenon known as emergence, in which new properties appear when smaller objects are joined together into a new one.6 This is visible everywhere in human life. For example, a high-school friend and I noticed one summer that girls would often walk together in groups of three, but that boys were almost always found alone or in pairs. We wondered why this was so, until my friend rather cryptically nailed it by saying that ‘three boys together are already a gang’. I believe his meaning was as follows: there is something vaguely menacing in the air as soon as three young males come together, and hence this practice is subtly discouraged under normal situations, which do not provide a welcome setting for menace. If the observation is correct, then three boys together have as a vague emergent property ‘gang-like threat to society’ that is found neither in two boys nor in three girls.

This is also true in the sciences, as can be seen with especial ease in a field such as organic chemistry: all organic compounds contain carbon, but there are millions of organic compounds, each with its own unique features.

Sometimes the defenders of emergence push their luck and make unnecessary additional claims, asserting for instance that the features of organic compounds ‘could not have been predicted’ from the features of carbon.

But quantum chemistry does allow us to predict the properties of larger molecules before they are actually created. And predictability is not even the point, since even if we could predict the features of all larger entities from their ultimate physical constituents, the ability to predict would not change the fact that the larger entity actually possesses emergent qualities not found in its components.

This is equally clear in human life. Perhaps a couple is about to be married, and all of their friends see clearly in advance that the marriage will be disas- trous. Now, let’s imagine that the friends of the couple are completely right: not only does the marriage fail, but it fails in precisely those ways and on the exact timetable that the friends had predicted. But notice that the predictability of this marital failure does not entail that the marriage is nothing more than the sum total of the two pre-existing indi- viduals who were married. In other words, the emergent real- ity of an object composed jointly of multiple parts (such as a married couple) does not hinge on the predictability or unpredictability of how it ultimately turns out. Emergence does not require mysterious results, but only that the mar- ried couple has joint features not found in either of the indi- viduals in isolation. The same would hold true if the friends were completely wrong and the marriage led to eternal and blissful harmony: the point is that the existence of the mar- riage as an emergent object over and above the two individ- ual partners has nothing to do with whether its success or failure could be foreseen.

Another prejudice infects portions of the history of phil- osophy in the view that only that which is natural truly exists. This doctrine is especially prominent in the philoso- phy of the German polymath G. W. Leibniz (1646–1716), who distinguishes sharply between what he calls ‘substances’ and ‘aggregates’. Substances are simple, soul-like entities (known as ‘monads’), all of them created by God at the beginning of time.7 By contrast, aggregates are compounds such as machines, circles of men holding hands, or pairs of diamonds glued together. For Leibniz such aggregates are merely laugh- able stand-ins for true substances, which can exist only by nature rather than artifice. OOO rejects this view given that machines, much like the Dutch East India Company (another example mocked by Leibniz), can be treated as unified objects no less than an atom or tiny vibrating string. In short, naturalness is no better as a criterion of objecthood than smallness or simplicity. As for the true criteria for what qualifies as an object, we will discuss them at the end of this chapter.

Third False Assumption:

everything that exists must be real.

One of the greatest fictional heroes of all time is surely the detective Sherlock Holmes, in the stories of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In writing these stories, Doyle tried to house his detective at a fictitious address on a real London street: namely, 221B Baker Street. Yet the very real London thoroughfare called Baker Street was later extended to go as far as the 200s, thereby putting the fictional flat of Holmes and Dr. Watson within the range of real-life city addresses. It is said that some of the Sherlock Holmes fans who visit the currently accepted address, now home to a gift shop and museum, labour under the misconception that the detective was a real historical person.

The retelling of this story usually provokes cruel laughter at the expense of these naive tourists. Yet there is a charming grain of truth in their ignorance: the fact that the detective is such a beloved and memorable character that one can easily imagine him resting comfortably at home on Baker Street, and picture him in a number of situations that did not actually occur in Doyle’s works (as in the current television series in which Holmes, played by Benedict Cumberbatch, solves cases in present-day London).

This brings us to a third objection to the global ambitions of string theory. Namely, a successful string theory would not be able to tell us anything about Sherlock Holmes, and this alone suffices to disqualify it as a ‘theory of everything’. For Holmes is a fictional personage, and thus was never composed of strings or of any other physical material.

Nor is it even necessary to invoke celebrity fictional characters such as those who inhabit novels and films, since we are surrounded at all times by fictions.

For example, any real orange or lemon, as I perceive it, is a vast oversimplification of the real citrus-objects in the world that are submitted to rough translation by the human senses and human brain.

The real orange or lemon is no more accessible to my human perception than it is to a mosquito or dog, whose organs translate the fruits differently into their own types of experience. In this respect, all of the objects we experience are merely fictions: simplified models of the far more complex objects that continue to exist when I turn my head away from them, not to mention when I sleep or die.

A successful string theory, like any fundamental theory of physics, is aimed entirely at the discovery of real physical entities rather than fictitious ones. And while it is already hard to imagine a basic physical theory adequately addressing any emergent mid- or large-sized entity (let us use ‘entity’ as another synonym for ‘object’ and ‘thing’), it is even harder to imagine a successful string theory teaching us anything about the fictional objects of literature and everyday perception, a field where natural science normally does not tread.

This is no small matter, since fictions are an integral part of human experience, and of animal life more generally.

Along with the examples already given, recall that we humans spend much of our time worrying about things that can never happen or simply never do. We are frequently deluded about our own capacities, whether under, or overestimating them.

We spend a large portion of our lives in nocturnal dreams, and despite recent criticism of psychoanalysis, it is doubtful that these dreams can be understood in purely chemical or neurological terms.

All of this is to say nothing of our entertainment media, which often feature dragons, rings of invisibility, aliens assaulting the earth, or the intimate lives of characters who exist for two hours on a screen before vanishing from the cosmos forever.

For many of us, artists such as Beethoven and Picasso are as worthy of esteem as Newton and Einstein, though the latter discuss such undeniable realities as light and moons while the former create pure fictions.

Any ‘theory of everything’ that dismisses the reality of fictions, or passes them over in silence, is by that fact alone unable to reach its goal of covering everything.

Fourth False Assumption:

everything that exists must be able to be stated accurately in literal propositional language.

Here are some scientific statements, chosen at random from the three books of science nearest to hand in my living room:

1. ‘Some hydrogen atoms can escape the Earth’s gravity and are lost to space, [while] some meteoritic material comes in (about forty-four tons per day on average) . . .’ (8)

2. ‘As Schrödinger pointed out, if M represents a cat and R takes two possible values . . . and the decay event triggers a device that kills the cat, then the cat will be neither alive nor dead after the measurement interaction, according to the orthodox interpretation.’9

3. ‘All other interventions, such as, for example, cold, heat, acids, alkalis, electrical currents, [the bell] responds to as any other piece of metal would. But we know . . . that

a muscle behaves in a completely different way. It responds to all external interventions in the same way: by contracting.’10

These are admirably formed statements conveying information that we hope to be true, though every scientist knows that many apparently rock-solid statements are later aban- doned or modified in the face of new evidence. Moreover, it is not just science that makes such statements.

History does the same. I need only turn elsewhere on my living room bookshelf:

‘But Mo-ch’o was growing old, and the Turks began to weary of his cruelty and tyranny. Many chiefs offered their allegiance to China, and the Bayirku of the upper Kerulen revolted.’11

Or simply this: ‘At this time, too, Venice had become the intellectual centre of Italy.’ (12)

All of these statements can be understood clearly by anyone with a basic secondary education. And of course we make statements of this sort constantly even in non-scholarly contexts.

It is easy to state as follows:

‘Leicester City stunned the sports world in 2016 by finishing on top of the English Premier League.’ Or I can look at the text messages on my phone and see that my wife, a university food scientist, needs me to pick up some items for her class on sensory analysis: ‘Here are the items I need before 11 o’clock. 1 pack of original Oreo cookies. 2 litres of drinking water. 1 carton of Florida Natural Original Orange Juice, with pulp.’

All these examples are literal statements that convey information directly. And thus it is easy to assume that nothing can be real unless we are able to refer to it in an accurate prose statement that conveys literal properties of the thing in question.

Apparently, the only alternative would be fuzzy metaphors or merely negative statements that teach us nothing.

The American philosopher Daniel Dennett is very much a literalist in this sense.

I am both amused and appalled by his mockery of wine-tasting in the following passage:

Could Gallo Brothers replace their human wine-tasters with a machine? . . . Pour the sample in the funnel and, in a few minutes or hours, the system would type out a chemical assay, along with commentary: ‘a flamboyant and velvety Pinot, though lacking in stamina’ – or words to such effect . . . [B]ut surely [note Dennett’s sarcasm] no matter how ‘sensitive’ or ‘discriminating’ such a system becomes, it will never have, and enjoy, what we do when we taste a wine: the qualia of conscious experience . . . If you share that intuition, you believe that there are qualia in the sense that I am targeting for demolition. (13)

To summarize, Dennett thinks that the wine is literally and adequately expressed by its ‘chemical assay’, though his imagined machine will also add sarcastic poetic commentary at the expense of human readers who disagree with his views. Nonetheless, he holds, there is no special conscious human experience of wine that would require the elusive figurative description of a flamboyant and velvety Pinot.

OOO holds that Dennett is wrong about this, and not just in the obvious sense that the taste of wine for humans resists any precise literal description. Instead, the claim of OOO is that literal language is always an oversimplification, since it describes things in terms of definite literal properties even though objects are never just bundles of literal properties (despite Hume’s view to the contrary).

It is not just that the chemical assay of the wine fails to do justice to the human experience of tasting wine, but that it fails to do justice even to the chemical–physical structure of the wine. This may sound like a startling claim, since the natural sciences are generally regarded as the court of final appeal in our era, just as the Church was in the medieval period.

But I will develop this anti-literalist claim throughout the present book. In so doing, I will build on the philosophical work of Heidegger, who also gives priority to poetic over literal language – though admit- tedly in ways that sometimes verge on Black Forest peasant kitsch, and though his statements against science are often needlessly extreme. 14

Thus I will make the case differently from how Heidegger did, though I agree with his basic line of reasoning: the reality of things is always withdrawn or veiled rather than directly accessible, and therefore any attempt to grasp that reality by direct and literal language will inevitably misfire.

In a sense, this point by Heidegger merely develops Aristotle’s ancient claim in his Metaphysics that individual things cannot be defined, since things are always concrete while definitions are made of universals. (15)

0 notes

Text

The Gnostic Machine: Artificial Intelligence in Stanislaw Lem's Summa Technologiae --- By Bogna Konior | Read >

0 notes

Text

The Theory of

Spontaneous Order

Anarchy in Action (1996) by Colin Ward

In every block of houses, in every street, in every town ward, groups of volunteers will have been organised, and these commissariat volunteers will find it easy to work in unison and keep in touch with each other ... if only the self-styled “scientific” theorists do not thrust themselves in ... Or rather let them expound their muddle- headed theories as much as they like, provided they have no authority, no power! And that admirable spirit of organisation inherent in the people ... but which they have so seldom been allowed to exercise, will initiate, even in so huge a city as Paris, and in the midst of a revolution, an immense guild of free workers, ready to furnish to each and all the necessary food.

Give the people a free hand, and in ten days the food service will be conducted with admirable regularity. Only those who have never seen the people hard at work, only those who have passed their lives buried among documents, can doubt it. Speak of the organising genius of the “Great Misunderstood”, the people, to those who have seen it in Paris in the days of the barricades, or in London during the great dock strike, when half a million of starving folk had to be fed, and they will tell you how superior it is to the official ineptness of Bumbledom.

Peter Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread

An important component of the anarchist approach to organisation is what we might call the theory of spontaneous order: the theory that, given a common need, a collection of people will, by trial and error, by improvisation and experiment, evolve order out of the situation — this order being more durable and more closely related to their needs than any kind of externally imposed authority could provide. Kropotkin derived his version of this theory from his observations of the history of human society as well as from the study of the events of the French Revolution in its early stages and from the Paris Commune of 1871, and it has been witnessed in most revo- lutionary situations, in the ad hoc organisations that spring up after natural disasters, or in any activity where there are no existing organisational forms or hierarchical authority. The principle of authority is so built in to every aspect of our society that it is only in revolutions, emergencies and “happenings” that the principle of spontaneous order emerges. But it does provide a glimpse of the kind of human behaviour that the anarchist regards as “normal” and the authoritarian sees as unusual.

You could have seen it in, for example, the first Aldermaston March or in the widespread oc- cupation of army camps by squatters in the summer of 1946, described in Chapter VII. Between June and October of that year 40,000 homeless people in England and Wales, acting on their own initiative, occupied over 1,000 army camps. They organised every kind of communal service in the attempt to make these bleak huts more like home — communal cooking, laundering and nurs- ery facilities, for instance. They also federated into a Squatters’ Protection Society. One feature of these squatter communities was that they were formed from people who had very little in common beyond their homelessness — they included tinkers and university dons. It could be seen in spite of commercial exploitation in the pop festivals of the late 1960s, in a way which is not apparent to the reader of newspaper headlines. From “A cross-section of informed opinion” in an appendix to a report to the government, a local authority representative mentions “an at- mosphere of peace and contentment which seems to be dominant amongst the participants” and a church representative mentions “a general atmosphere of considerable relaxation, friendliness and a great willingness to share”.1 The same kind of comments were made about the instant city of the Woodstock Festival in the United States: “Woodstock, if permanent, would have become one of America’s major cities in size alone, and certainly a unique one in the principles by which its citizens conducted themselves.”2

An interesting and deliberate example of the theory of spontaneous organisation in operation was provided by the Pioneer Health Centre at Peckham in South London. This was started in the decade before the Second World War by a group of physicians and biologists who wanted to study the nature of health and of healthy behaviour instead of studying ill-health like the rest of the medical profession. They decided that the way to do this was to start a social club whose members joined as families and could use a variety of facilities in return for a family membership subscription and for agreeing to periodic medical examinations. In order to be able to draw valid conclusions the Peckham biologists thought it necessary that they should be able to observe human beings who were free — free to act as they wished and to give expression to their desires. There were consequently no rules, no regulations, no leaders. “I was the only person with authority,” said Dr Scott Williamson, the founder, “and I used it to stop anyone exerting any authority.” For the first eight months there was chaos. “With the first member-families”, says one observer, “there arrived a horde of undisciplined children who used the whole building as they might have used one vast London street. Screaming and running like hooligans through all the rooms, breaking equipment and furniture,” they made life intolerable for everyone. Scott Williamson, however, “insisted that peace should be restored only by the response of the children to the variety of stimulus that was placed in their way”. This faith was rewarded: “In less than a year the chaos was reduced to an order in which groups of children could daily be seen swimming, skating, riding bicycles, using the gymnasium or playing some game, occasionally reading a book in the library ... the running and screaming were things of the past.”

In one of the several valuable reports on the Peckham experiment, John Comerford draws the conclusion that “A society, therefore, if left to itself in suitable circumstances to express itself spontaneously works out its own salvation and achieves a harmony of actions which superim- posed leadership cannot emulate.”3 This is the same inference as was drawn by Edward Allsworth Ross from his study of the true (as opposed to the legendary) evolution of “frontier” societies in nineteenth-century America.

Anarchy in Action (1996)

by Colin Ward | Read >

0 notes

Text

What is the relationship between consciousness and the brain ?

0 notes

Text

The Space Of Possible Minds

Today’s debates about artificial intelligence fail to grapple with deeper questions about who we are and what kind of future we want to build.

Must Read on Noema >

0 notes

Text

Let’s say that intelligence ‘measures an agent’s general ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments’, following the definition adopted by the computer scientists Shane Legg and Marcus Hutter.

A Formal Measure of Machine Intelligence

Read on Are.na >

0 notes

Text

What are the possible forms of consciousness,

and how might they differ from the human experience?

***

0 notes

Text

The Hyperbolic Geometry of DMT Experiences: Symmetries, Sheets, and Saddled Scenes

Read Article >

The Geometry of DMT States

This is an essay on the phenomenology of DMT. The analysis here presented predominantly uses algorithmic, geometric and information-theoretic frameworks, which distinguishes it from purely phenomenological, symbolic, neuroscientific or spiritual accounts. We do not claim to know what ultimately implements the effects here described (i.e. in light of the substrate problem of consciousness), but the analysis does not need to go there in order to have explanatory power. We posit that one can account for a wide array of (apparently diverse) phenomena present on DMT-induced states of consciousness by describing the overall changes in the geometry of one’s spatiotemporal representations (what we will call “world-sheets” i.e. 3D + time surfaces; 3D1T for short). The concrete hypothesis is that the network of subjective measurements of distances we experience on DMT (coming from the relationships between the phenomenal objects one experiences in that state) has an overall geometry that can accurately be described as hyperbolic (or hyperbolic-like). In other words, our inner 3D1T world grows larger than is possible to fit in an experiential field with 3D Euclidean phenomenal space (i.e. an experience of dimension R2.5 representing an R3 scene). This results in phenomenal spaces, surfaces, and objects acquiring a mean negative curvature. Of note is that even though DMT produces this effect in the most consistent and intense way, the effect is also present in states of consciousness induced by tryptamines and to a lesser extent in those induced by all other psychedelics.

0 notes

Text

Aut nunc aut nihil. Each moment contains an eternity to be penetrated — yet we lose ourselves in visions seen through corpses’ eyes, or in nostalgia for unborn perfections. -TAZ

0 notes

Text

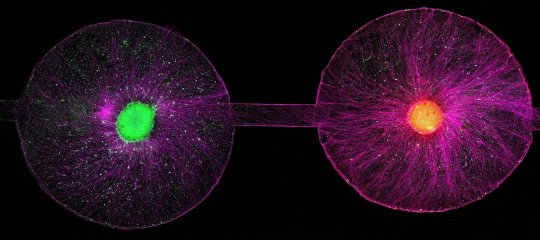

Formation of synaptic connections b/w neurons derived from human embryonic stem cells in an organ-on-chip system. This image was generated using confocal microscopy, capturing multiple 2D images at diff. depths to create a 3D reconstruction.

via [Dr. Arthur Chien, Dr. Ann Na Cho]

Organ-on-chip system enabling the synaptic conjugation between 3D human embryonic stem cells | Read>

0 notes