#erín moure

Text

VB: Once, after listening to a text of mine mixing French and English, a first-year US student said reproachfully: “I didn’t understand the parts in French; I felt alienated.” I replied something like: “Relax! It’s okay, and liberating, not to understand sometimes and to realize that reality escapes in the form of languages one doesn’t know.” It’s also humbling to know that myriads of unknown or unidentified languages construct alternative realities. So, yes, there’s a need to reassert that opacité can be generative, totally! On the purely editorial side: Mosadeq pushed us to publish Recovery with some French in it, just like Récupérer had some English. The “tests” were written directly in English.

EM: Understanding is vastly overrated! For one thing, it can make us stick with what we already know or “almost know”—that is, what coincides with our prejudices—and where’s the fun in that? I prefer the lostness, the sense of reinventing myself, that comes from reading cacophonically polylingual texts such as Recovery. These texts meet me where I actually “am,” where I am “being.” Can you comment on queer practice and its relation to translation, even within one language? Does being gay/queer/lesbo—as we both and each are—have an attentional effect on writing and language practice that makes verisimilitude already always suspect?

VB: Although some say that queerness doesn’t change anything of the writing experience, I think that practicing opacité is in part linked with the experience of not fitting in because I’m gay/queer and often reminded that I don’t belong. Plus, there are things about queer desire—however that absolute singular and the singularity of that desire are antithetical to each other—and queer practices of total exhibition of the self while hiding it that fundamentally change our relation to fidelity, to the shifty contexts of language and languages, and to the way we build new techniques of the body for ourselves. Part of my writing comes from a fundamental need to make cheer because we’ve been and sometimes still are so close to the catastrophic social and mental consequences of being other. We’ve been through the melancholy of refusal, and so the urge is to free oneself from intimidations and intimations. Making cheer means a politics, questioning verisimilitude, finding ways to continue the fluidity that inhabits us, whoever we are.

Vincent Broqua Interviewed by Erín Moure, A book and its translation engage in a “serious lightness” across languages and categories.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

2. Thus seen, i took the temperature of the.

3. Ieri, in the present futuro

4. mijloc

5. Nimeni pe stradă. numai noi.

6. lilas, lilas.

Ring out the hours.

6. liliac: a blind bat holding up the roof of a cave

with his blind feet, or an armful of lilacs

5. On the street no one to witness the street into a

street. (Where are we?)

4. The middle of the story exposed like a bare belly.

3. Time kept unfolding tomorrow. (When are we?)

2. The word seemed alive: we began to pulse its

temperature.

—Oana Avasilichioaei & Erín Moure, from “Living Pr...” (I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women, Les Figues Press, 2012)

#quotations#poetry#conceptual writing#oana avasilichioaei#erín moure#i'll drown my book#currently rereading

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erín Moure’s Translation of Wilson Bueno’s Paraguayan Sea (Nightboat, 2017) — The Bind

0 notes

Text

Border Lyrics

"...within the playground of the multilingual lyric, which crosses borders with the flick of a code-switch, the hierarchies around gender and nation-states enforced by a monolithic approach to language may be temporarily dismantled."

Subsisters and Paraguayan Sea, two recent SPD titles in translation, reviewed by Henk Rossouw at Boston Review!

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

from Erín Moure’s RETOOLING FOR A FIGURATIVE LIFE (Vallum Chapbook Series No. 32)

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

You had no language.

History had sliced

the beauty of your lips

with a knife from inside.

—Lupe Gómez, Galician poet

translated by Erín Moure

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Each time, time’s rupture must be admitted, for every translation destroys time. This is not “an impossible sentence with no meaning.” It is the time or tense of all translation, all writing. Like the future anterior of the phrase “I died,” all translation appears as a monster in time itself.

Erín Moure, O Resplandor

1 note

·

View note

Quote

In some ways, writing poetry means to attend: to be attentive to everything to do with the senses, every type of traffic, desert, utopia, absence, thought, sensation, music, dream, darkness, love, life. Above all, it means hearing, listening to the other materials that lift a language toward suspension of its servitudes: toward the suspension of its passwords and impositions; suspension of the delusions of an ‘I’, the delusions of communication. The language of the poem has an osmotic relation with muteness, and it might be said that the absence of articulated language is its power, its possibility; this means stretching the ear, heightening the intensity of our attention.

Chus Pato, Always Against the Idols: A Conversation with Chus Pato and Erín Moure

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

O título desta intervención debería ser o mellor verso de John Ashbery

Karl Blossfeldt

Para escribir este texto leo por décima, undécima ou duodécima vez o Atlas de Alba. Teño esa sorte. Releo de novo algún poema, percorréndoo por sabe Deus xa que volta. Reléoo co mesmo xesto co que acendo a luz do cuarto, repetido, cotián e non por iso, se o desautomatizásemos, menos asombroso. Releo o Atlas como cando había poucos libros: podería falar do Medievo ou dos meus quince anos, tanto ten (aquela pequena biblioteca de poesía —menos de dez títulos— visitados unha e outra vez, os poucos versos que sei de memoria). Leo o Atlas como a poeta di que os cazadores inuit tallan ósos cuxas formas imitan as liñas da costa. E así, aos poucos, “os símbolos traballan o seu propio desxeo”.

Vaia por diante que, mentres falo aquí hoxe e fago balance e cartografía dos poemas de Alba, non renuncio a falar como amigo, convencido como estou de que a amizade e a intelixencia son, co permiso da admirada Estíbaliz Espinosa, neuronas irmás.

Subliño o Atlas de azul e vermello. Cando remato, non podo evitar pensar nunha representación do sistema circulatorio: poemario convertido en manual de anatomía ou libro de texto. Pequenos fíos de veas azuis e arterias vermellas. Un tecido, vasos comunicantes. Nese sentido, a miña primeira tentación é facer de Atlas un despece, un tratado. Hai neste libro cinco ciclos, un polo e un ensaio final. Hai neses cinco ciclos tres historias apócrifas, unha nova denominación das especies, un mapa, unha carta de navegación... Porén, escollo ganduxar, escollo fixarme no fío que terma dos poemas, na voz que os convoca (penso aquí no son indeterminado do metal que golpeamos, no eco, no canón do Sil, no rastro da vea que aparece e marcha sobre a carne branquísima de quen se debruza día e noite no scriptorium).

Falar da voz é falar do límite, non como término, senón como transgresión. Leo en Agamben: “O único contido da revelación é o en si pechado, o velado: a luz non é senón o porvir da escuridade en sí mesma”. Neste sentido, Alba escolle unha voz mesta con puntos de luz, un caudal que se vai cargando de materiais e que brilla baixo o sol do mediodía ou a lúa chea: nenas con bengalas nunha praia en Provincetown (así as fotografou Robert Frank e así mas fixo chegar Alba o pasado outubro).

Digo nenas e penso que quen fala é a miúdo a “pequena occidental” do primeiro poema (na paxinación e no tempo) deste libro: “Historia apócrifa dos tulipáns ou as alucinacións nos Países Baixos”. Unha nena que viaxa, que medra, aprende, retruca, inventa e nunca, nunca, nunca deixa de confiar na maxia. Neste sentido, Alba é digna herdeira da Penélope soñada por Xohana Torres, da súa liberdade. E éo tamén —herdeira— pola súa posición no campo literario. Permitiredes que afirme que nunca unha estrea editorial foi tan agardada coma esta, que poucas veces unha poeta inédita (aínda que na esteira de ata que punto pode ser inédita unha poeta na era de internet habería moito que dicir), pero poucas veces unha poeta inédita acadou tal nivel de influencia nas súas coetáneas e tan boa acollida dentro e fóra das nosas fronteiras. Penso, neste sentido, na curiosidade que os poemas de Alba espertan en tradutoras como Erín Moure ou Harriet Cook, no recoñecemento para a tradución ao inglés da “Historia apócrifa do descubrimento das migracións”, da man de Jacob Rogers, que se converteu no primeiro poema galego en abrir a sección “Poem-a-Day” da web da prestixiosa Academy of American Poets. Pero é que ademais, Alba é posiblemente a mellor crítica literaria da súa xeración, da miña xeración (tanto por escrito como nas ondas da Radio Galega); é unha das académicas que mellor ten pensado o suxeito poético en Galicia; unha das articulistas máis singulares (dende o seu “Gabinete de curiosidades” en Tempos Novos ata a serie “An octopus” na revista Cactus); e tamén unha das poetas máis difíciles de fixar, de situar, de clasificar. Esa manía que tanto parecía volver estilarse por estes lares hai dous ou tres anos e que, afortunadamente, foi esquecida xa.

Pero regresemos sobre o libro. Sobre o meu exemplar de Atlas e os seus subliñados en azul e vermello, a súa anatomía. Aparece entón de novo a pequena occidental receptora de historias, falando e rindo en múltiples linguas e linguaxes. Emerxe tamén a nena que rilla nunha mazá a carón dos cantís de Calais. E eu pregúntome se as dúas son a mesma nena ou só quedan para xogar. Para xogar ás Polly Pocket ou ao voleibol coas rapazas das montañas Karakorum. Porque hai nestes poemas unha vontade de xogo, de transparentar materiais, idiomas, expresións artísticas. Unha vontade por veces científica, académica, e, outras, puramente fantasiosa, imposible (como a mellor ciencia teórica).

Direi tamén, se son fiel á miña relectura última, que o Atlas está non só cheo de límites rotos e dobres costuras, senón que o habitan tamén seres en constante cambio: adultos pel-de-cedro, homes-teixo, avoas cuxo xesto imita o da caléndula, Safo transmutada en cigarra que cae, ou os Asmat, ese tribo de Papúa Occidental que se autodenomina a xente das árbores. Eles poderiamos ser nós, lectoras. Neste sentido a transgresión, o que a voz dos poemas imaxina, non se detén no cruce e no tratamento de referencias históricas ou xeográficas, senón que o modifica todo, mesmo o propio libro, que devén dragón atrapado entre dúas eclipses. Dragón feito de escrita. Voz de dragón.

“intuir o bosque na dispersión das sementes”, dise. Penso entón na lectura, nas bibliotecas. En como a lectura nos interrompe e nos tranforma. Sáennos ao camiño no Atlas, explícitamente: Marianne Moore, Gertrude Stein, Anne Carson, Charles Dickens, Paul Celan, Ezra Pound, Claudio Rodríguez, Juan Andrés García Román, Charles Wright, Wallace Stevens, John Ashbery, Edgar Allan Poe, Jorie Graham, D. H. Lawrence. Todas elas, as febras do tapiz, a dama e mais o unicornio. Fago para vós a miña pequena escolla de flores.

Dúas mestras recoñecidas na dedicatoria, certo parentesco, unha liñaxe. De Marianne Moore, a técnica, a intención, a vontade firme de escribir allea a todo, a independencia da muller que pensa o mundo mesmo se o mundo non pensa coma ela ou nin sequera pensa nela. De Anne Carson, a voz que un día foi, o fragmento, o ano en que lemos Homes nas súas horas libres, pero sobre todas as cousas a liberdade.

Despois recoñezo a fascinación pola imaxe, polo torrente, velaí Jorie Graham, lida nunha biblioteca dun país estranxeiro. Era verán, escribiámonos, coma sempre, por messenger. Velaí La adoración de García Román ou, ocórreseme agora, aquela Julieta Valero que cantaba á anatomía dos príncipes escandinavos en Los heridos graves. Aí están, parellas, fascinantes, herdeiras desta alucinación luminosa, as mozas de Alba: “dúas rapazas que choraban diante dos espellos e usaban vaqueiros máis celestes / ca os seus iris” ou “as adolescentes do baño cruzaron a sala, recordo, / proxectando fugazmente a escena dunha marisma / cos reflexos dos seus cabelos rosa flamengo”.

Está tamén, na lectura destes poemas, na dicción e no risco, a Chus Pato que escribe: “pregúntome se nesta frase caben todos os teixos da cidade libre de París” —París!— ou aqueloutra maís rebuldeira de m-Tala. E está, por suposto, Francisco Cortegoso, o contemporáneo co que mellor dialoga a poesía de Alba. Está en homenaxe (brillo de escama, reflexo celeste, columna vertebral), pero tamén antes de marchar, véxase o parentesco destes versos de Alba onde o pai “sabe despegar a sombra / do corpo / dos paxaros”, con aqueloutros de Cortegoso onde a árbore “Distánciase na altura, mídese / na sombra. // Sostena / o ceo. / Pode caer”. E eu digo: caemos.

Imaxino unha santa en cuxa cabeza se abre un libro. Podería ser unha santa ou unha dama habitando a cidade de Christine de Pizan ou un cadro de Remedios Varo. Repito unha vez máis, no Atlas, tan libre, tanto ten. Digo santa ou dama e tanto ten porque Carson lembraríanos que todas elas son incómodas interrupcións no curso da historia. Ese poder outorgámosllo á lectura, ao verso, ao lugar onde todo encaixa e rompe. Onde é posible dicir: todo encaixa e rompe.

Por último, os “Ensaios”. Os ensaios de Alba coma unha sorte de poética. Notas a pé de páxina, a pé de ollo. Os ensaios en aberto, en Instagram, escritorio desordenado, colección de mostras. Penso que este libro se comezou a escribir daquela —2013— cando nos coñecemos e Alba investigaba sobre o poema en prosa, sobre a presenza do ensaio no poema. Lembro a primeira vez que a escoitei recitar, o poema contiña a humidade dos manglares. Despois, lembro ler con fascinación, “O corpo e as bestas”, unha serie da que permanecen vestixios no “Tríptico” ao xeito de Millet que contén este Atlas. Despois, Capadocia. Despois, os tulipáns.

Ao final do ensaio sobre a Canna indica Karl Blossfleldt di, tras aparcar a un lado a bicicleta: “Se lle dou a calquera unha equisetácea, non terá problema ningún en facer un aumento fotográfico —todo o mundo pode—. Pero observala, prestarlle atención e descubrir as súas formas, iso, iso é un cantar distinto”. Nese cantar, na súa precisión, afina este libro.

Comezaba dicindo que o título desta intervención debería ser o mellor verso de John Ashbery, poeta querido pola autora e por quen fala. Esa é unha débeda que teño con Alba. Esa era a miña intención hoxe, estar á altura do Atlas, buscar palabras que o iluminen. Non atopei, por desgraza, ese único verso Ashbery. O que diga toda a miña admiración, todo o amor, toda a amizade. O único que agardo, e permítanme o extraliterario, é que a conversa onde busquemos ese verso dure todo o tempo do mundo.

[Este texto foi lido na primeira presentación de Atlas de Alba Cid, o 18 de decembro de 2019 na Libraría Couceiro de Santiago de Compostela]

1 note

·

View note

Quote

One intriguing aspect of Pillage Laud, a book of poems supposedly “written by a computer” (back cover), is that “Erín Moure,” the so-called “biological product in the usual state of flux” (109), not to mention in big scare quotes, is not alone in her little writer’s garret dreaming up these sexy mechanized cantigas for her lesbian lover. She has cohorts in the production, co-authors, you might say, one being the sentence-generator program MacProse, and the other being MacProse’s monster-father-programmer, Charles O. Hartman. We also can’t forget Pillage Laud’s originally accented “Erin Mouré” from 1999, and probably the other E(i)r(í)ns too, with or without scary quotes and accents, and, who knows, maybe even Elisa Sampedrín in utero.[iii] Truly a distributed cybernetic network is this pillaged laud to plugs, bottoms, whips, wanks, vaginas, and harnesses, a “powerful infidel heteroglossia,” as Donna Haraway, one of Erín’s continuous muses, would say in her infamous “A Cyborg Manifesto” (181). Or “I was a front” and “We are my veils,” as Pillage Laud would say (32, 14). Or, as perhaps only my friend Erín would get the engine to say, “My identity had grinned”

“Like plugging into an electric circuit”: Fingering out Erín Moure’s lesbo-digit-O! smut poems

0 notes

Text

Weekly Wrap Up

Tabletop & video-games:

Control, PS4.

Manga, manhwa, graphic novels, comic-strips, fic & books:

Furia do Corpo, João Gilberto Noll.

Erín Moure’s Translation of Wilson Bueno’s Paraguayan Sea (Nightboat, 2017) — The Bind

William Friedkin Unrealized Projects – IndieWire

Podcasts, playlists, JAMS, EPs & albuns:

[Caioverso] CAIOVERSO #117 - Anime Véio: Rayearth #caioverso

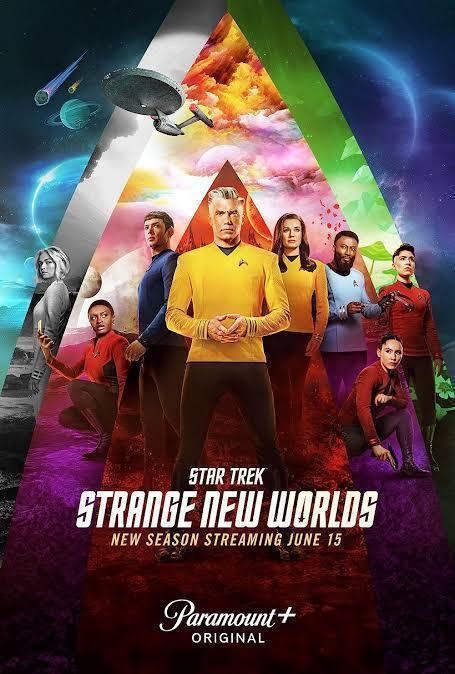

[Super Amibos] LIVE - Star Trek: Strange New Worlds (Episódios S02E06, S02E07 e S02E08) #superAmibos

[AoQuadrado²] Re:En² - Eden: it's an Endless World Vol. 05-08 #aoquadrado

TVshows, TVseries & movies:

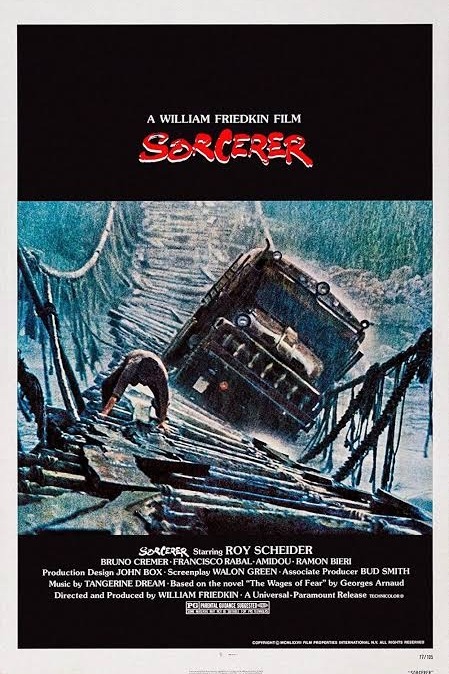

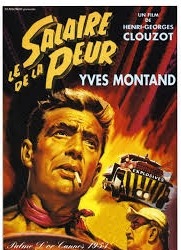

Filhas do fogo (1978)/ Sorcerer (1977) /The wages of fear (1953)

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds s2e6-10/ Kochikame s2e3,4 / Galaxy Express 999 s1e2-4

0 notes

Photo

EXCERPT from Introduction:

Some may ask: Why poetry? Why respond in a kind of language where meaning is not always transparent, when the subject matter of sexual abuse might rather invite language that states categorically the terms of the experience, that does not allow for misinterpretation or ambiguity? Shouldn’t this be language that gets straight to the point rather than travelling slant, arriving wonky or misshapen? But, we ask, whose point would that language be arriving at? If it wasn’t women who shaped the vocabulary and syntax we widely recognize as legible, then following these forms could, for some, feel like another act of docility.

–Emily Critchley and Elizabeth-Jane Burnett, 2018

One of my poems:

MISSISSIPPI

Last night at a Love’s

truck stop, a man

told me he would like

to slice me up,

boil and eat my liver

and rape me after,

I’m pretty sure,

in that order.

With his eyes

he spoke those words,

and if you don’t

believe me

(“How could you know

for sure?”)

then you’ve never been

a woman, or else.

The rain and the cows

don’t care.

The corn doesn’t

ask or doubt.

And there’s

a southern sadness

buried in everything

I pass down this dark

road driving tonight.

–Amy King

CONTRIBUTORS:

KAT ADDIS

SASCHA AURORA AKHTAR

RACHAEL ALLEN

NUAR ALSADIR

RAE ARMANTROUT

MEI-MEI BERSSENBRUGGE

ZOË BRIGLEY THOMPSON

ELIZABETH-JANE BURNETT

MAIRÉAD BYRNE

J.R. CARPENTER

SOPHIE COLLINS

JENNIFER COOKE

EMILY CRITCHLEY

ALISON CROGGON

AMY CUTLER

JEAN DAY

CARRIE ETTER

AMY EVANS

MEGAN FERNANDES

KAI FIERLE-HEDRICK

HEATHER FULLER

ISABEL GALLEYMORE

SUSANA GARDNER

SUSAN GEVIRTZ

ELIZABETH GUTHRIE

SARAH HAYDEN

SUSAN HOWE

JACQUELINE KARI

AMY KING

DEIRDRE KOVAC

LOUISE LANDES LEVI

AGNES LEHOCZKY

JAZMINE LINKLATER

FRANCESCA LISETTE

SO MAYER

CAROL MIRAKOVE

KATHRYN MOCKLER

MARIANNE MORRIS

ERÍN MOURE

CHARLOTTE NEWMAN

SANDEEP PARMAR

FRANCES PRESLEY

JÈSSICA PUJOL DURAN

SINA QUEYRAS

NAT RAHA

NISHA RAMAYYA

JOAN RETALLACK

CHRISTIE ANN REYNOLDS

SUSAN M. SCHULTZ

CONNIE SCOZZARO

SOPHIE SEITA

ZOË SKOULDING

ROSIE ŠNAJDR

VERITY SPOTT

REBECCA TAMÁS

ELIZABETH TREADWELL

CATHERINE WAGNER

ROSMARIE WALDROP

SAMANTHA WALTON

CAROL WATTS

EMILIA WEBER

ELIZABETH WILLIS

SARA WINTZ

ELISABETH WORKMAN

0 notes

Text

PW Poetry Annex April 2017

It’s national poetry month, which means that PW’s annual poetry feature is here. We have brief interviews with 4 poets and listings of some politically oriented collections worth checking out. If you’re trying to write a poem a day this month, I’m sorry to hear that. You should try that in February, like I do, because it has fewer days. On to the books!

Hairdo. Rachel B. Glaser (Song Cave)

The January Children. Safia Elhillo (Univ. of Nebraska)

Planetary Noise: Selected Poetry. Erín Moure (Wesleyan Univ.)

Poems in the Manner of.... David Lehman (Scribner)

Scale. Nathan McClain (Four Way)

Further Problems with Pleasure. Sandra Simonds (Univ. of Akron)

Scald. Denise Duhamel (Univ. of Pittsburgh)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Planetary Noise - Selected Poetry of Erín Moure

Planetary Noise – Selected Poetry of Erín Moure

This collection of poetry came to me by way of ModPo. Anna sent it to me after I was the first caller in during a webcast sometime last year. This collections got me interested in Moure and I hope to read more. Moure and more is extra fun since she uses so much word play and explains much of her process in this collection.

The introduction provides insight into her life with languages– Moure…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

F WORD WARNING

Wombwell Rainbow Interviews

I am honoured and privileged that the following writers local, national and international have agreed to be interviewed by me. I gave the writers two options: an emailed list of questions or a more fluid interview via messenger.

The usual ground is covered about motivation, daily routines and work ethic, but some surprises too. Some of these poets you may know, others may be new to you. I hope you enjoy the experience as much as I do.

Amanda Earl

is a Canadian poet, publisher, prose-writer, visual poet and editor who lives in Ottawa, Ontario. Her first and only poetry book so far is Kiki (Chaudiere Books, 2014). Amanda is the managing editor of Bywords.ca and the fallen angel of AngelHousePress. Connect with Amanda on Twitter @KikiFolle or visit AmandaEarl.com for more information.

The Interview

1. What inspired you to write poetry?

I didn’t even realize I was writing poetry until my mid thirties. I scrawled on pads of paper from my parents’ workplaces, all kinds of confessional stuff and complaints and lists. I made notes on index cards about everyone I knew and filed them in a metal box. I just wrote. I didn’t label it. I heard nothing but poetry by men from early childhood and up, whether it was in school or recitations by my father: Shakespeare, Victorian morality poetry, Edward Leer. I liked the rhyming and the sound play, and the images, but I rarely related to it. I dismissed the thought of poetry from my head.

In my mid-thirties, I was going through a period of depression and searched the Internet for solace. I came across the poet Mary Oliver’s poem, Wild Geese, Lorna Crozier’s Carrots (https://jeveraspoetryanthology.weebly.com/carrots.html) poem and also Gwendolyn MacEwen’s fascinating and dark mythological poems. These excited me and made me realize that perhaps I was also writing what could be called poetry. I still wasn’t sure.

2. Who introduced you to poetry?

My father, I suppose, but it didn’t feel like an introduction. He was always reciting poetry to me as a child.

3. How aware were you of the dominating presence of older poets?

More like the domineering presence. Since school curricula for literature were dominated by dead white men, I knew nothing about women poets until I found them in my Internet search in the 90s. I wish I’d known about Plath and Sexton in my teenage years; although what darkness I would have dredged up back then under their influences… When I first started to realize I was writing poetry, it took me some time to find out about poets like Anne Carson who is willing to step out of traditional form to make poetry out of the long lost fragments of Sappho, accordion books about grief, little chapbooks placed in a box so readers can rearrange at will. Or Caroline Bergvall and her mesmerizing engagements with Old Norse. There’s just so much possibility out there for poetry and yet quite often the same white men, dead or alive, have their work published again and again and win prizes and are taught as the poetry that matters.

4. What is your daily writing routine?

According to Mason Currey in his book, Daily Rituals: Women at Work, the photographer Diana Arbus ritual was sex. (https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-daily-routines-10-women-artists-joan-mitchell-diane-arbus?fbclid=IwAR2fXdj7OUukk2c_-RUU8mxIhor8FRPaSWU3yJ0_f_W0t_DzUR8LQ3y3ej0) I usually start my day off with a good wank and at least an hour of pervy chat with a few random strangers. I shivered this morning after a particularly good orgasm. After that I drink Irish Breakfast tea, burn some incense and write or go outside, if it’s not too hot or cold, and wander about until I have no choice but to write. I carry a red journal with me for snippets of overheard conversation, some weird sound play that comes to me, or a doodle. My red journals are smeared in paint and tea stains.

5. What motivates you to write?

1. Lorca’s concept of the duende (https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Spanish/LorcaDuende.php) Death is near. I don’t want to be immortal, I just want to continue the conversation. I’m influenced by ghosts, such as Oscar Wilde and Djuna Barnes, Leonora Carrington, Jean Cocteau and Beatrice Wood.

2. Alienation. In some ways I live the standard North American life, but in others I don’t. I write and publish others full-time. I don’t have a nine to five job. I don’t drive. I don’t own property. I live downtown. My husband and I are in a passionate and open marriage. I write to reach out to that one kindred misfit in hope that they feel less alone. The Tragically Hip song “It’s a good life if you don’t weaken,” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gwNVxvczgCs&feature=youtu.be) comes to mind. “Let’s get friendship right.”

6. What is your work ethic?

I follow three principles: whimsy, exploration and connection. I want to play; I want to learn new stuff and I want to write things that connect with those alienated by convention and the lonely. I punched a timecard as a late teen and I saw my parents punching those same damn cards. I loathe systems and routines and any attempts by external authorities to dictate my time, so I rebel against any system. I write because I breathe. It’s just part of me. Writing isn’t as tough as plumbing or surgery.

I serve the work rather than dictating what the work will be. I once spent three months learning about the sonnet because the manuscript I was working on had to be made up of sonnets, not because I wanted to but because the content required it somehow. I wrote three of the damn things and gave up. They were awful. That manuscript remains unpublished.

I try to remain grateful and humble to have the opportunity to write. Sometimes my work gets published, which is a huge honour. I try to be careful not to let my ego tell me how great I am, because I’m not. I’m just in the right place at the right time and have found the right publisher somehow. This happens rarely.

I try not to take up too much space and leave space for writers who do not have the benefits granted by white colonialist publishing policies and attitudes that continue to prevail. I try to promote and publish 2SLGBTQIA, BIPOC, and D/deaf and disabled writers and look for ways I can support them when I can. I don’t do this enough.

7. How do the writers you read when you were young influence you today?

I read the Exorcist, Mad Magazine, Archie Comics and Harlequin romance novels as a youngster. These works gave me a sense of irreverence that is important for my writing. In high school and university I studied French, German and Italian and finally got excited by literature. Dante made me fascinated with Heaven and Hell; Kafka made me fear insects; Baudelaire made me want to drink red wine. Rimbaud showed me that synaesthesisa, which I have, was not just something I experienced. Later I read Milton’s Paradise Lost. Early influencers of the long poem, I suppose, and the epic. I am writing an anti-epic these days. Red wine isn’t something I can stomach easily anymore. Now and then I’ll have a little Lagavulin in the tub.

8. Who of today’s writers do you admire the most and why?

Nathanaël for Je Nathanaël, for working in the spaces between genres and writing so beautifully of the body.

Sandra Ridley for her ability to write long, mesmerizing poems and read them as if they are incantations.

Christine McNair for syntactic daggers, sounds that are bitten off, and charm.

Anne Carson for her sense of play and versatility.

Canisa Lubrin for Voodoo Hypothesis, which is the only book she’s written so far, and it’s brilliant. I am awed by the skill in these poems, not just on a poetic level (diction, imagery, lineation, structure, balance) but also by the power of one writer’s willingness and ability to so effectively dismantle and bring to light the ongoing effects of racism while offering in-depth and tangible illustrations of the othered.

Alice Notley for the Descent of Alette, a most extraordinary long poem.

rob mclennan for his prolific writing and quiet poetry and bizarre wee stories.

Amber Dawn for brave femme truths and incorporating subjects that are traditionally taboo in mainstream CanLit, such as sex work.

Joshua Whitehead for the sheer invention and brilliance of Full Metal Indigiqueer which takes down the literary canon so skillfully.

The writers in the anthology Stairs and Whispers: D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back Edited by Sandra Alland, Khairani Barokka & Daniel Sluman (http://ninearchespress.com/publications/poetry-collections/stairs%20and%20whispers.html)

for the versatility and beauty of their writing. It’s good writing and more people should be aware of it.

Ian Martin for self-deprecating comedy.

Erín Moure for Elisa Sampedrin.

Lisa Robertson for the gift of the sentence.

Gary Barwin for his whimsy and willingness to play in numerous genres and media.

I wish Djuna Barnes was here. I’m always looking for a modern-day equivalent. Nightwood was an exquisite and poetic novel.

9. Why do you write, as opposed to doing anything else?

I don’t just write. I also play with paint, make visual poetry, which some might say is a form of writing, run two small presses, which do a bunch of things. I spend too much time on social media. I make countless lists. I watch a lot of films and tv. I listen to music. I wank. I fuck my husband. We cook glorious meals together. I go on long rambles and spend a lot of time in cafés. I cry and worry every day for the persecuted in this topsy turvy era where the Ogre in the House of White is making us all fear that the end of the world is close.

All these activities and emotions enter into my writing in some way.

10. What would you say to someone who asked you “How do you become a writer?”

I don’t know. I focus less on being a writer and more on writing. Writer sounds like a title and titles have a bunch of preconceived expectations I can’t satisfy. Same with poet. I just write.

But I guess, I’d tell them to be gentle on themselves, surround themselves with books, art, film and whatever inspires them. Ignore prescriptive rules, such as write what you know. Heather O’Neill, a fiction writer I admire, once said that for her to write, she has to be angry about something. At least that’s what I remember her saying at an Ottawa International Writers Festival event.

For me, I have to feel emotion of some sort, whether it is anger, sadness, love… I guess I would say to the person who wants to write that they are going to have to make sure that they don’t numb themselves. It’s easy in this era to want to numb ourselves against all the pain and suffering and power games going on, but when we numb ourselves, we don’t feel and if we don’t feel, it’s hard to respond. Writing, whether it’s directly political or not, is a response to what’s around us. I think it takes a great deal of empathy to write. It takes close listening and close watching.

Find a mentor. I’ve been fortunate in that rob mclennan has been extremely supportive of my work. He’s been honest when the stuff is shite. I still remember taking my first of his poetry workshops in 2006 and him telling me I was writing zombie poems.

He’s published many of my chapbooks through above/ground press and my book, Kiki through Chaudiere Books. He always encourages me to write and he has introduced me to many of the poets I mention in my list of influences and more. He does this not only for me, but for numerous others. It’s amazing!

11. Tell me about the writing projects you have on at the moment.

I was fortunate to have received a grant from the City of Ottawa for Beast Body Epic, a long poem that I began a few years after a major health crisis in 2009 and have been tinkering with ever since. So I’m going to finish tinkering and submit the manuscript for the fourth time toward the end of the year.

I have a smaller manuscript called The Milk Creature and Mother Poetry, inspired by Diana di Prima, one of the women active in the Beat poetry scene.

I’m working on The Vispo Bible, a life’s work to translate every chapter, every book, every verse of the Bible into visual poetry. I began in 2015 and have completed about 300 pages so far.

In 2018, I began work on a novel. Its working title is The Nightmare Dolls’ Imperfect Reunion. It’s about women, health, ageing, friendship, gender, and it has a helluva soundtrack. (https://open.spotify.com/playlist/5B1GAgN046EdtrBLXiNoni?si=NIbexI5mQqKnr54qfmJ7ZQ)

Amanda Earl is a Canadian poet, publisher, prose-writer, visual poet and editor who lives in Ottawa, Ontario. Her first and only poetry book so far is Kiki (Chaudiere Books, 2014). Amanda is the managing editor of Bywords.ca and the fallen angel of AngelHousePress. Connect with Amanda on Twitter @KikiFolle or visit AmandaEarl.com for more information.

Wombwell Rainbow Interviews: Amanda Earl F WORD WARNING Wombwell Rainbow Interviews I am honoured and privileged that the following writers local, national and international have agreed to be interviewed by me.

0 notes