#erskine sanford

Text

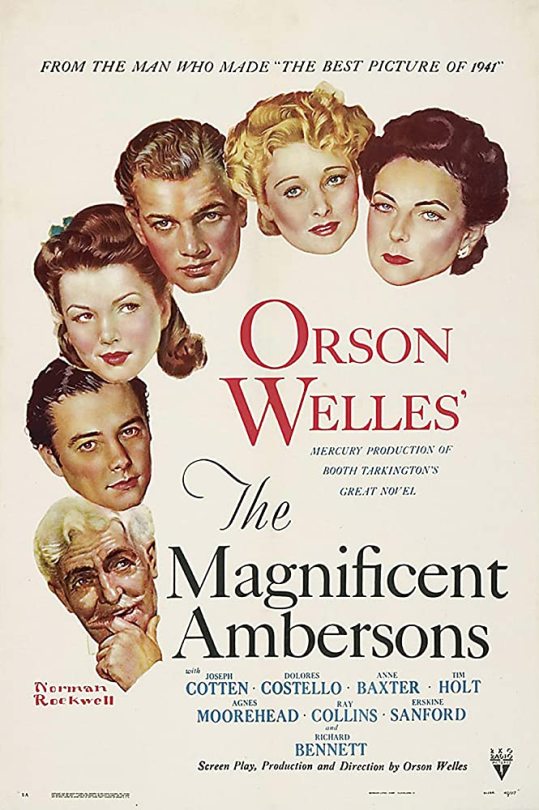

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942)

#i think every movie should end like this#the magnificent ambersons#Joseph Cotten#Dolores Costello#Anne Baxter#Tim Holt#Agnes Moorehead#Ray Collins#Erskine Sanford#Richard Bennett#orson welles#m

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthday remembrance - Erskine Sanford #botd

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Impact

“Charming” isn’t a word normally associated with film noir, yet it fits Arthur Lubin’s IMPACT (1949, TCM, Tubi, Plex, Prime, YouTube). From the intricate plot in which everything falls neatly into place to the location photography in San Francisco and Larkspur, CA, to, most importantly, the not quite love scenes between Brian Donlevy and Ella Raines, it’s an ongoing delight. Wealthy industrialist Donlevy is driving to Denver for a plant opening when his wife (Helen Walker) contrives to have her lover go along for the ride and kill him. The lover is neither very good with a tire iron nor with a steering wheel and ends up dead in a fiery car crash while Donlevy, stunned to discover what the Mrs. had been doing, wanders the countryside until he winds up at war widow Raines’ filling station. Romance is as inevitable as Hollywood usually makes it. Meanwhile, police detective Charles Coburn, in one of his least fussy performances, tries to make sense out of the plot.

With lots of scenes shot on location (including the same San Francisco hotel where Kim Novak’s character stayed in VERTIGO), IMPACT is a lot sunnier than most film noirs, but the plot is so twisted and Walker such a great femme fatale it doesn’t matter. The script, by Dorothy Davenport (that’s Mrs. Wallace Reid to you) is a masterpiece of efficiency, with key facts and events planted effortlessly and events communicated through telegrams, newspaper headlines and even a radio broadcast by gossip columnist Sheilah Grahame. Raines was never distinctive enough to be a star, but she’s a darned good actress and lots better than you’d expect from a film noir good woman. Donlevy, whose leading man days were largely over by 1949, has beautiful moments as he realizes what’s going on in his life. Anna May Wong deserved a lot better than her brief role as Walker’s maid, but she delivers a solid performance in her next-to-last film. Her friend (and merkin?) Philip Ahn is on-hand in old-age makeup as her uncle. You may also spot Robert Warwick as a police captain, Clarence Kolb as chairman of Donlevy’s board, silent great Mae Marsh as Raines’ mother, Jason Robards, Sr. as a judge, Erskine Sanford as a doctor and horror film standby Morris Ankrum as Donlevy’s assistant.

#film noir#arthur lubin#dorothy davenport#brian donlevy#ella raines#helen walker#anna may wong#charles coburn#robert warwick#clarnce kolb#mae marsh#jason robards#erskine sanford#morris ankrum

0 notes

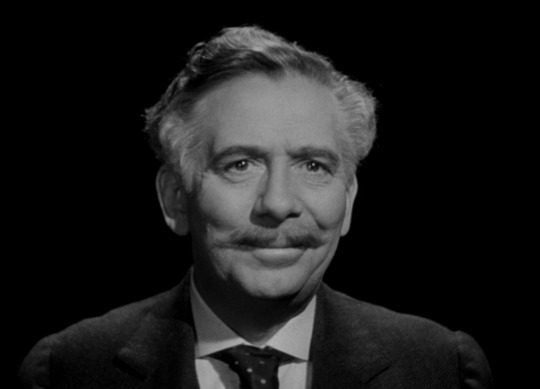

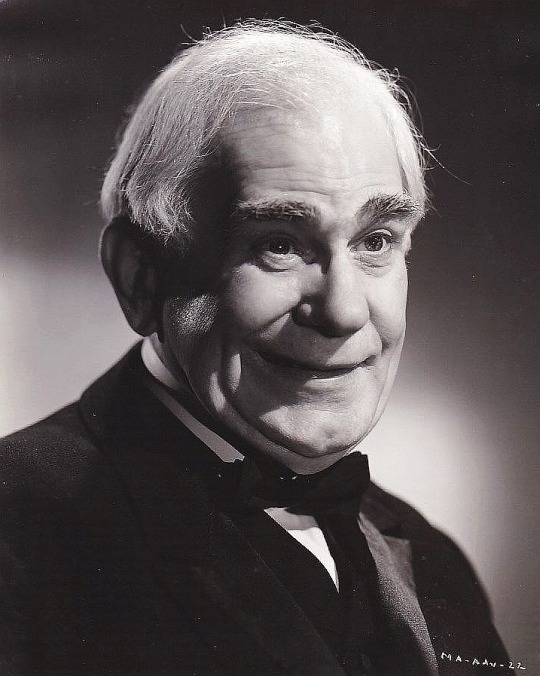

Photo

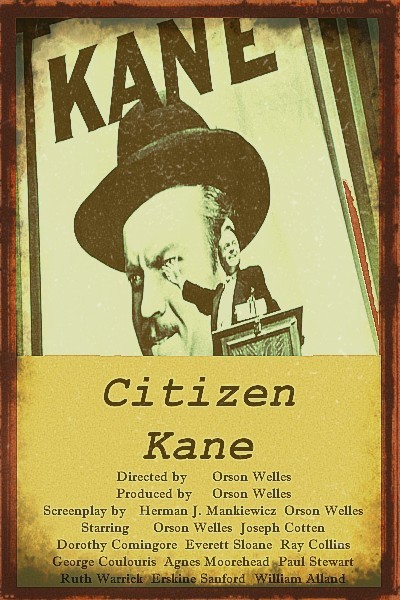

Joseph Cotten, Orson Welles, and Everett Sloane in Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941)

Cast: Orson Welles, Joseph Cotten, Dorothy Comingore, Agnes Moorhead, Ruth Warrick, Ray Collins, Erskine Sanford, Everett Sloane, William Alland, Paul Stewart, George Coulouris. Screenplay: Orson Welles, Herman J. Mankiewicz. Cinematography: Gregg Toland. Art direction: Van Nest Polglase, Perry Ferguson. Film editing: Robert Wise. Music: Bernard Herrmann.

Things I don't like about Citizen Kane:

The "News on the March" montage. It's an efficient way of cluing the audience in to what it's about to see, but is it necessary? And was it necessary to make it a parody of "The March of Time" newsreel, down to the use of the Timespeak so deftly lampooned by Wolcott Gibbs ("Backward ran sentences until reeled the mind")?

Susan Alexander Kane. Not only did Orson Welles leave himself open to charges that he was caricaturing William Randolph Hearst's relationship with his mistress, Marion Davies, but he also unwittingly damaged Davies's lasting reputation as a skillful comic actress. We still read today that Susan Alexander (whose minor talent Kane exploits cruelly) is to be identified as Welles's portrait of Davies, when in fact Welles admired Davies's work. But beyond that, Susan (Dorothy Comingore) is an underwritten and inconsistent character -- at one point a sweet and trusting object of Kane's affections and later in the film a vituperative, illiterate shrew and still later a drunk. What was it in her that Kane initially saw? From the moment she first lunges at the high notes in "Una voce poco fa," it's clear to anyone, unless Kane is supposed to have a tin ear, that she has no future as an opera star. Does she exist in the film primarily to demonstrate Kane's arrogance of power? A related quibble: I find the portrayal of her exasperated Italian music teacher, Matiste (Fortunio Bonanova), a silly, intrusive bit of tired comic relief.

Rosebud. The most famous of all MacGuffins, the thing on which the plot of Citizen Kane depends. It's not just that the explanation of how it became so widely known as Kane's last word is so feeble -- was the sinister butler, Raymond (Paul Stewart) in the room when Kane died, as he seems to say? -- it's that the sled itself puts so much psychological weight on Kane's lost childhood, which we see only in the scenes of his squabbling parents (Agnes Moorehead and Harry Shannon). The defense insists that the emphasis on Rosebud is mistakenly put there by the eager press, and that the point is that we often try to explain the complexity of a life by seizing on the wrong thing. But that seems to me to burden the film with more message than it conveys.

And yet, and yet ... it's one of the great films. Its exploration of film technique, particularly by Gregg Toland's deep-focus photography, is breathtaking. Perry Ferguson's sets (though credited to RKO art department head Van Nest Polglase) loom magnificently over the action. Bernard Herrmann's score -- it was his first film -- is legendary. And it is certainly one of the great directing debuts in film history. But I don't think it's the greatest film ever made. In the top ten, maybe, but it seems to me artificial and mechanical in comparison to the depiction of actual human life in Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu, 1953), the elevation of the gangster genre to incisive social and political critique in the first two Godfather films (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972, 1974), the delicious explorations of obsessive behavior in any number of Alfred Hitchcock movies, the epic treatment of Russian history in Andrei Rublev (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1966), and the tribulations of growing up in the Apu trilogy (Satyajit Ray, 1955, 1956, 1959). And there are lots of films by Howard Hawks, Preston Sturges, Luis Buñuel, François Truffaut, Robert Bresson, and Jean-Luc Godard that I would rewatch before I decide to watch Kane again. There are times when I think Welles's debut film has been overrated because he had a great start, battled a formidable foe in William Randolph Hearst, and inadvertently revealed how conventional Hollywood filmmaking was -- for which Hollywood never forgave him. It's common to say that Citizen Kane was prophetic, because the downfall of Charles Foster Kane anticipated the downfall of Orson Welles. That's oversimple, but like many oversimplifications it contains a germ of truth.

3 notes

·

View notes

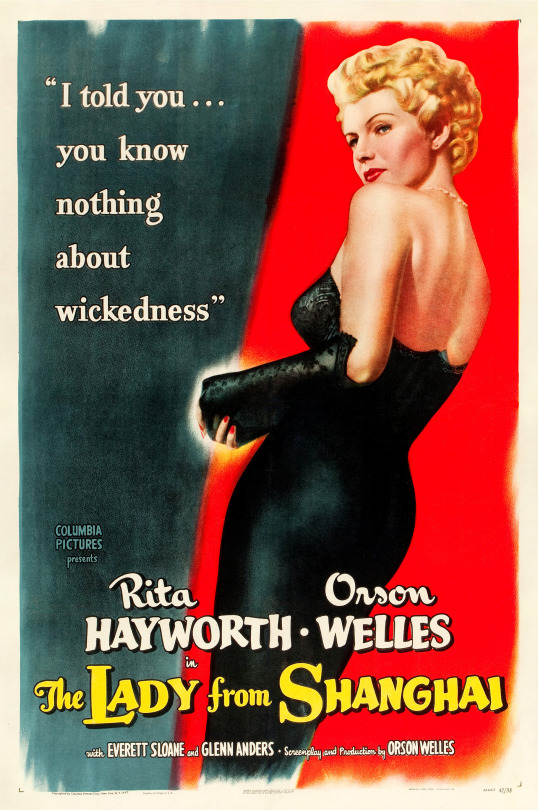

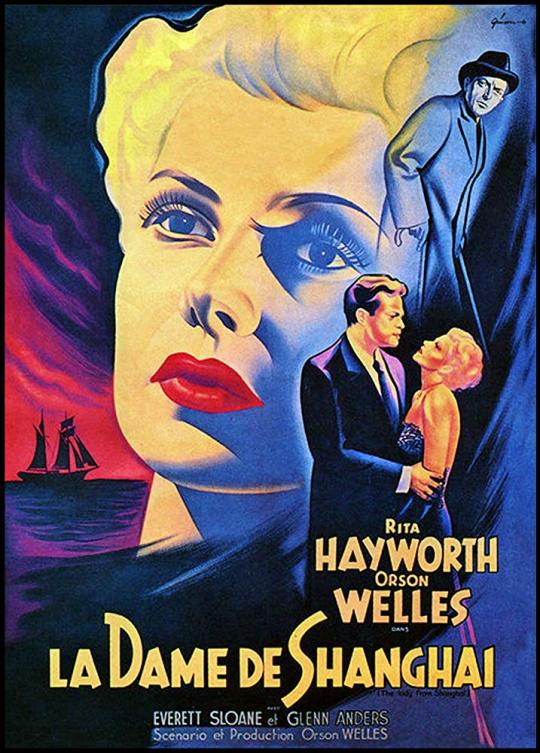

Photo

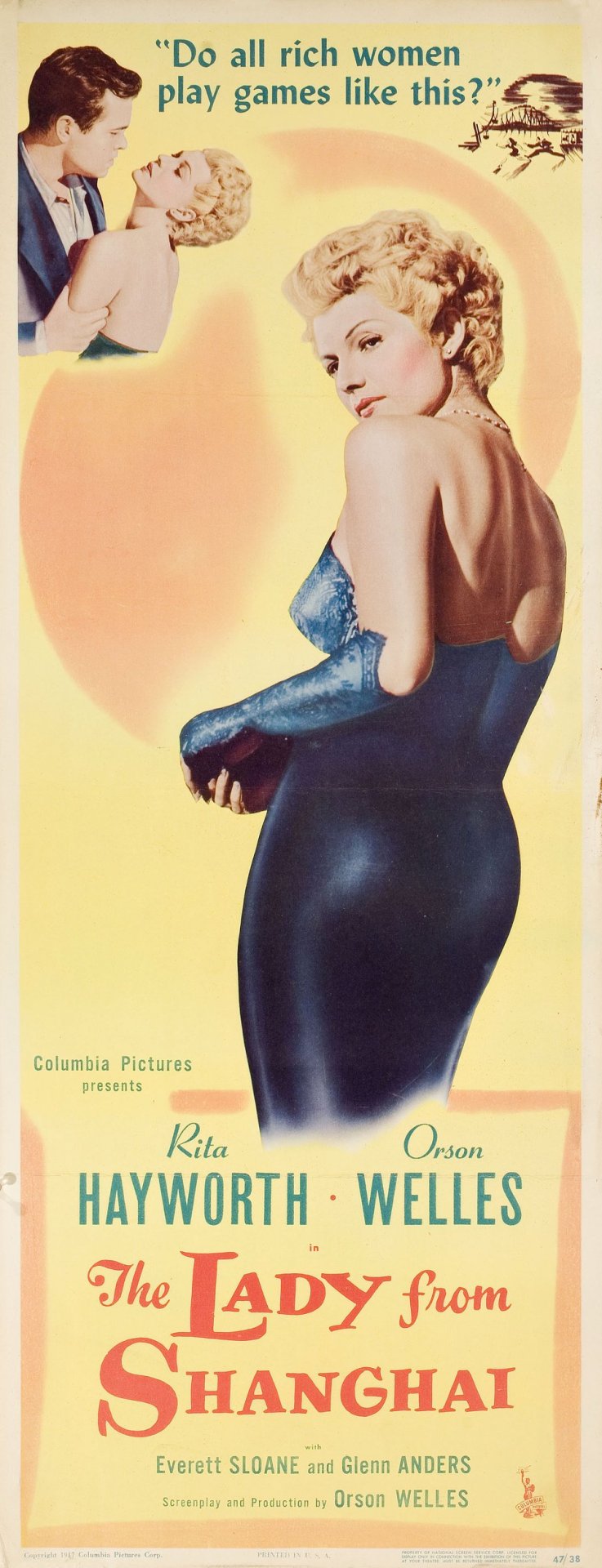

The Lady from Shanghai (1947) Orson Welles

February 5th 2022

#the lady from shanghai#1947#orson welles#rita hayworth#everett sloane#glenn anders#ted de corsia#gus schilling#erskine sanford#carl frank#if i die before i wake#black irish#take this woman#the girl from shanghai

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

- My gosh, the old times are certainly starting all over again.

- Old times, not a bit. There aren't any old times. When times are gone, they're not old, they're dead. There aren't any times but new times.

The Magnificent Ambersons, Orson Welles (1942)

#Orson Welles#Joseph Cotten#Dolores Costello#Anne Baxter#Tim Holt#Agnes Moorehead#Ray Collins#Erskine Sanford#Richard Bennett#Stanley Cortez#Bernard Herrmann#Robert Wise#1942

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#680 #Citizen Kane

#Citizen Kane#Oscar#Orson Welles#Herman J. Mankiewicz#John Houseman#Joseph Cotten#Dorothy Comingore#Agnes Moorehead#Ruth Warrick#Ray Collins#Erskine Sanford#Everett Sloane

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

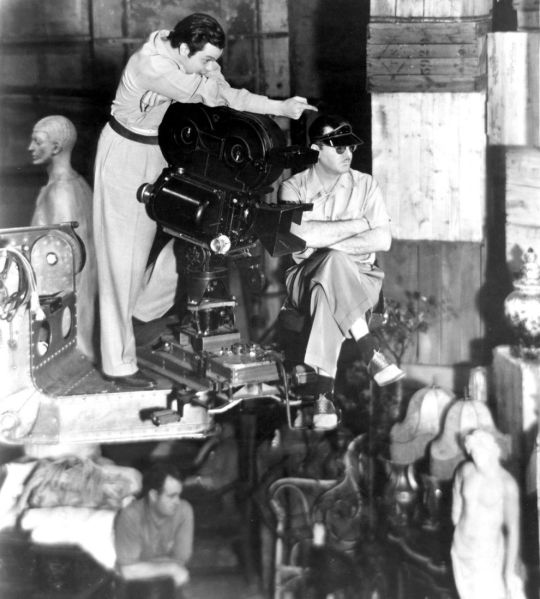

Orson Welles on set with cinematographer Gregg Toland.

@tcmparty live tweet schedule for the week beginning Monday, March 23, 2020. Look for us on Twitter…watch and tweet along…remember to add #TCMParty to your tweets so everyone can find them :) All times are Eastern.

Sunday, March 29 at 8:00 p.m.

CITIZEN KANE (1941)

The investigation of a publishing tycoon's dying words reveals conflicting stories about his scandalous life.

#schedule#orson welles#joseph cotten#everett sloane#agnes moorehead#dorothy comingore#ruth warrick#paul stewart#william alland#erskine sanford#gregg toland#bernard herrmann#herman mankiewicz#a mankewicz family weekend#turner classic movies#tcm#tcm party#classic movies#classic film#alan ladd#if you look closely

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soberba (1942)

The Magnificent Ambersons

Direção: Orson Welles; Fred Fleck e Robert Wise (diretores não-creditados das sequências adicionais);

Roteiro: Orson Welles; Joseph Cotten e Jack Moss (roteiristas não-creditados das sequências adicionais); baseado no romance homônimo de Booth Tarkington;

Gênero: Drama; Romance;

País: EUA.

A mutilação que os produtores incidiram sobre este projeto pessoal e relativamente autobiográfico de Orson Welles constitui-se como uma das maiores tragédias cinematográficas de todos os tempos. Afastado da direção, os momentos finais da narrativa estiveram nas mãos de Fred Fleck e Robert Wise, que modificaram deliberadamente o roteiro original de Welles: isso justifica a inexpressividade do elenco próximo do encerramento do filme e o encaminhando para o final feliz destoante do conjunto da narrativa anteriormente desenvolvida. Ainda assim, Soberba consiste num potente drama familiar que expõe suas forças tanto no pretexto superficial, quanto nas camadas mais profundas de sentido.

Nos anos finais do século XIX, Isabel Amberson (Dolores Costello), detentora do mais importante sobrenome da cidade, esteve noiva do proeminente, porém boêmio, empresário Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotten). Ela, no entanto, casara-se com Wilbur Minafer (Don Dillaway), com quem teve apenas um filho: o arrogante e orgulhoso George Minafer (Tim Holt). Passados quase vinte anos, Isabel e Eugene, ambos viúvos, encontram-se novamente. Embora os tempos sejam outros e as convenções sociais já não sejam as mesmas, George opõe-se terminantemente à amizade ou romance entre Eugene e sua mãe, em defesa da honra e do símbolo de poder erigido em torno do sobrenome Amberson.

Tendo como pano de fundo este drama familiar sobre a trajetória que acompanha o esplendor e a decadência dos Ambersons, uma aristocrática família de Indianápolis, a narrativa do filme versa sobre as mudanças sociais promovidas pela passagem do tempo e pelos aprimoramentos tecnológicos: através das relações sociais entre as duas famílias - Ambersons e Morgans - o principal embate em questão é a substituição do esplendor aristocrático pela burguesia insurgente. A passagem do tempo e as transformações sociais encontram-se metaforizadas na narrativa pela invenção do automóvel: neste sentido, a discussão entre George e Eugene sobre as consequências de uma fábrica de automotivos durante um juntar na mansão dos Ambersons é extremamente significativa. Ironicamente, próximo final do filme, quando encontrava-se já destituído das benesses do sobrenome, George é atropelado por um automóvel, como se a narrativa do filme materializasse o solapamento da aristocracia pela burguesia.

Soberba mostra-se também como um excelente ensaio técnico de Orson Welles. A sugestão de perspectivas ópticas é extremamente significativa: a imponência que George acredita possuir é, o tempo todo, materializada pela maneira como a câmera enquadra o personagem. Outra cena exemplar sobre a impecabilidade técnica de Welles é a do baile de recepção de George, quando a câmera “baila” entre os casais dançantes, pescando aqui e ali trechos de diálogos constituintes da narrativa.

⭐ 4.1 / 5.0

#Filme#Movie#Drama#Romance#Drama Movie#Romance Movie#Soberba#The Magnificent Ambersons#Orson Welles#Fred Fleck#Robert Wise#Joseph Cotten#Dolores Costello#Anne Baxter#Tim Holt#Agnes Moorehead#Ray Collins#Erskine Sanford#Richard Bennett

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

11.22.19

#watched#film#letterboxd#the lady from shanghai#orson welles#rita hayworth#everette sloan#glen anders#ted de corsia#erskine sanford#gus schilling#lou merrill#evelyn ellis

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#citizen kane#movies#orsen welles#joseph cotten#dorothy comingore#everett sloane#ray collins#george coulouris#agnes moorehead#paul stewart#ruth warrick#erskine sanford#william alland#illustration#vintage art#alternative movie posters

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph Cotten, Orson Welles, Everett Sloane, and Erskine Sanford in CITIZEN KANE (1941)

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ministry of Fear

With enemy secrets hidden in a cake and the shoulders of a suit, the 1944 adaptation of Graham Greene’s MINISTRY OF FEAR would seem to be perfect material for Alfred Hitchcock. Instead, it’s the work of a rather disappointed Fritz Lang. Lang resented working for a producer who had written the screenplay, cutting all of Greene’s moral ambiguities, and wouldn’t let him do any rewrites. Ray Milland stars as a man recently released from a mental hospital who stumbles on a spy ring in an idyllic British village, where he accidentally wins a cake containing military secrets at the local charity fete. The film plays with appearances throughout. You don’t learn Milland was in an asylum until after he’s bid a cordial farewell to the man in charge. As the action progresses, little is what it appears to be, creating another Langian image of the dark city. Whereas in MAN HUNT (1941) Nazi thugs lurked around every corner, in MINISTRY OF FEAR sophisticated Nazi agents have infiltrated the upper echelons of society and even the Ministry of Home Security. The long silent patches in the film are very powerful, with Lang and cinematographer Henry Sharp creating powerful images of paranoia and Milland doing good physical work. But the main character has a bad habit of singing his lines the more upset his character, and it wears a little thin here. There are some fascinating supporting characters —Marjorie Reynolds and Carl Esmond as siblings running a charity to help refugees; Dan Duryea, Hillary Brooke and Alan Napier as sleek upper-class enemy agents; Erskine Sanford as a private detective — but most of them don’t have enough to do. Percy Waram is particularly fun as a lurking figure who turns out to be a Scotland Yard inspector, winning the war through dogged persistence and impeccable manners.

0 notes

Photo

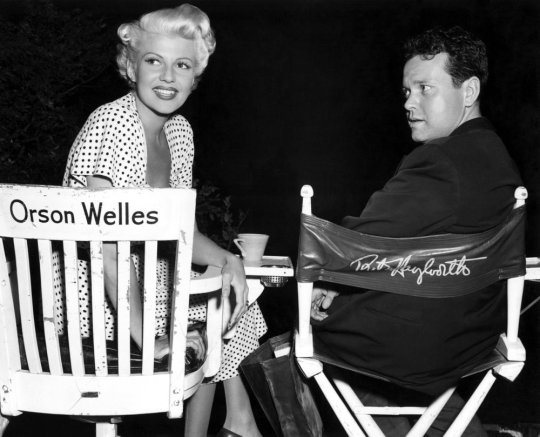

Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth in The Lady From Shanghai (Orson Welles, 1947)

Cast: Rita Hayworth, Orson Welles, Everett Sloan, Glenn Anders, Ted de Corsia, Erskine Sanford, Gus Schilling, Carl Frank, Louis Merrill, Evelyn Ellis, Harry Shannon. Screenplay: Orson Welles, based on a novel by Sherwood King. Cinematography: Charles Lawton Jr., Rudolph Maté, Joseph Walker. Art direction: Sturges Carne, Stephen Goosson. Film editing: Viola Lawrence. Music: Heinz Roemheld.

Like most of Orson Welles's Hollywood work, The Lady From Shanghai is the product of clashing wills: Welles's and the studio's -- in this case, Columbia under its infamous boss Harry Cohn. And as usual, the clash shows, sometimes in Welles's brilliance, such as the celebrated shootout in a hall of mirrors at the film's end, and sometimes in his indifference to the material: Is there any real excuse for the farcical courtroom scene that so violates any sense of consistency in the film's tone? Welles miscast himself as the protagonist, Michael O'Hara, a two-fisted Irish seaman, complete with an accent that he must have picked up in his youthful days in the Dublin theater. His soon-to-be ex-wife, Rita Hayworth, was forced upon him by Cohn, whom he angered by having her cut her hair and dye it blond. Her Elsa Bannister is the epitome of the treacherous film noir femme fatale, but it's hard to say whether the screenplay -- mostly by Welles -- or Hayworth's limited acting ability prevents the character from coming into focus. The real casting coup of the film is Everett Sloane as as Elsa's crippled husband, Arthur, and Glenn Anders as his partner, George Grisby. I use the word "partner" intentionally, because the film dodges around the Production Code in its hints that Bannister and Grisby are more than just law-firm partners, evoking the stereotypical catty and mutually destructive gay couple. Welles insisted on filming on location, which means we get some fascinating glimpses of late-1940s Acapulco and San Francisco, shot by Charles Lawton Jr. and the uncredited Rudolph Maté and Joseph Walker. In short, the movie is a mess, but sometimes a glorious mess.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

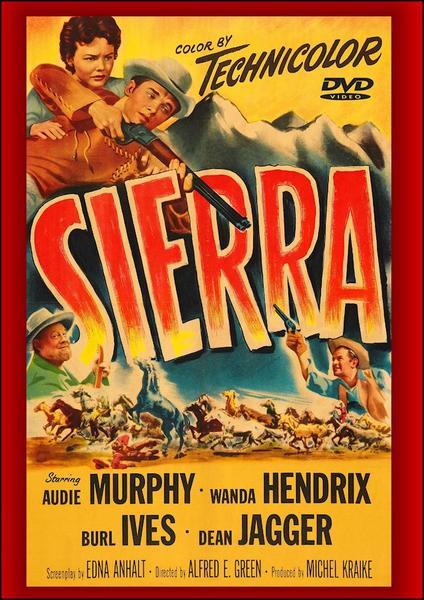

Sierra 1950

#sierra#audie murphy#dean jagger#burl ives#wanda hendrix#elisabeth risdon#tony curtis#james arness#john doucette#richard roper#roy roberts#elliott reid#sara allgood#griff barnett#erskine sanford#houseley stevenson#gregg martell#i stanford jolley#ted jordan#jack ingram#westerns#old west#western#western movie#western movies

13 notes

·

View notes