#fifteenth-century painting

Note

If it strikes your fancy, for kiss prompts-A king and a herald, 19? (I'm not in any of your other fandoms lmao)

19. a kiss for luck

#em draws stuff#henry v 1989#le roy d'armes des françois (dit montjoye)#mille fleur tapestries were not a really a big thing until much later in the fifteenth century but What Ever#thank you for this request it took me FIVE DRAFTS but it was fun for literally all of the time#this version is heavily based on 'god speed!' by edmund blair leighton (a painting I am sure we all know on tumblr dot com)#the composition of which I have squished together for 1) more touching and 2) not having to draw the horse#imagine the horse. a horse is implied but you're not going to get to see it.#...a significant amount of this was put together while staying up until 2am watching fall out boy amvs. yes it's 2023.#I have done a significant bit of Goofin' It on this one but also I have not drawn these fellows in a while. need to get back into practice.#also would you believe it I was looking back on my (wretched and blurry) screencap collection and montjoy's gloves are blue?? neat!!

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The website Closer to Van Eyck lets you zoom all the way in on Jan & Hubert Van Eyck’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb altarpiece in Ghent, which is presently being restored (it’s a bit of a work in progress).

Of course, it’s an altarpiece, so the religious iconography is quite literally front and centre. But I rarely look at those bits.

Because there’s a whole world to explore in the details.

these are a few of my favourite bits.

This is the birth of landscape painting right here. In the backgrounds of pious Northern Renaissance pictures of saints.

#painting#van eyck#Ghent altarpiece#northern renaissance#renaissance#belgium#fifteenth century#15th century#art#tiny worlds#details in art

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The New Testament scarcely mentions Mary. She is brought into the story mainly to emphasize Jesus's divine conception and birth. Her presence is noted once or twice, but little is made of it. In the centuries that followed, however, Mary was exalted to ever-higher positions of glory. She is the subject of many of our most famous and beautiful works of art. In light of what we have learned about the Goddesses of the ancient Near East, it is interesting that Mary is shown not only as the Madonna with her child, but standing on the crescent moon or with stars circling her head. She takes on many of the ancient Goddess symbols and is often painted as a larger-than-life figure. She is also shown being crowned Queen of Heaven, absorbing the title of the Goddess. It may be that the need of the people for a female deity was so great that the Christian Church might not have survived without the elevation of Mary to this exalted position. We need to look carefully, however, at just what aspects of the Goddess Mary was allowed to retain and what the results were in the lives of women.

Mary was taken up to heaven and seated with god the father and his divine son Jesus. She became the main intercessor between human beings and the divine. She was called Mother of God and Queen of Heaven, but she was not made a full-fledged member of the Godhead. The Church used her to satisfy the need for a female presence in Christianity but also to keep women in a subordinate position. Her purity as a virgin was exalted and women were taught to strive for that purity and to obey the divine (male) will. At the same time she is, of course, a mother, and women were taught to bear as many children as possible. But Mary did it while remaining a virgin; other women, in order to be mothers, must be tainted by sexuality. If they remain pure they cannot be like Mary the Mother; if they become mothers they cannot be like Mary the Virgin. No matter what they do they are guilty and inferior.

Mary's stance is: "Let it be to me according to your word." She is passive, obedient, and pure. She sits on a throne but has little power, certainly none of the power or independence of the earlier Goddesses or their free sexuality. Nevertheless, the doctrine of her virginity gave women a way out of the role of submissive wife and bearer of children. When the cult of Mary was at its height, thousands of women escaped into convents, communities of women. There they developed skills and talents in the arts and in the administration of large estates. Many abbesses wielded significant power and controlled sizable amounts of wealth.

It is interesting that, just as the veneration of Mary reached its height in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Protestant Reformation reasserted the dominance of the male divinities. One of Luther's major reforms was the closing of nunneries, and Mary is notably absent from all formulations of Protestant theology and ritual. Whereas Catholic women have suffered from their attempts to imitate an impossible model, Protestant women have had no exalted female model of any kind. Mary's presence has been used by the Catholic Church to reinforce the subordination of women, and her absence has been used by Protestantism to reinforce their insignificance.

-Shirley Ann Ranck, Cakes for the Queen of Heaven

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

I typed up the Pentiment bibliography for my own use and thought I’d share it here too. In case anyone else is fixated enough on this game to embark on some light extra-curricular reading

I haven’t searched for every one of these books but a fair few can be found via one of the following: JSTOR / archive.org / pdfdrive.com / libgen + libgen.rocks; or respective websites for the journal articles.

List below the cut!

Beach, Alison I, Women as Scribes: Book Production and Monastic Reform in Twelfth-Century Bavaria. Cambridge University Press, 2004

Berger, Jutta Maria. Die Geschichte der Gastfreundschaft im hochmittelalterlichen Mönchtum die Cistercienser. Akademie Verlag GmbH, 1999

Blickle, Peter. The Revolution of 1525. Translated by Thomas A. Brady, Jr. and H.C. Erik Midelfort. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985

Brady, Thomas A., Jr. “Imperial Destinies: A New Biography of the Emperor Maximilian I.” The Journal of Modern History, vol.62, no.2, 1990. pp. 298-314

Brandl, Rainer. “Art or Craft? Art and the Artist in Medieval Nuremberg.” Gothic and Renaissance Art in Nuremberg 1300-2550. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986

Byars, Jana L., “Prostitutes and Prostitution in Late Medieval Barcelona.” Masters Theses. Western Michigan University, 1997

Cashion, Debra Taylor. “The Art of Nikolaus Glockendon: Imitation and Originality in the Art of Renaissance Germany.” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, vol.2, no.1-2, 2010

de Hamel, Christopher. A History of Illuminated Manuscripts. Phaidon Press Limited, 1986

Eco, Umberto. The Name of the Rose. Translated by William Weaver. Mariner Books, 2014

Eco, Umberto. Baudolino. Translated by William Weave. Boston, Mariner Books, 2003

Fournier, Jacques. “The Inquisition Records of Jacques Fournier.” Translated by Nancy P. Stork, San Jose University, 2020

Geary, Patrick. “Humiliation of Saints.” In Saints and their cults: studies in religious sociology, folklore, and history. Edited by Stephen Wilson. Cambridge University Press, 1985. pp. 123-140

Harrington, Joel F. The Faithful Executioner: Life and Death, Honor and Shame in the Turbulent Sixteenth Century. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013

Hertzka, Gottfied and Wighard Strehlow. Große Hildegard-Apotheke. Christiana-Verlag, 2017

Hildegard von Bingen. Physica. Edited by Reiner Hildebrandt and Thomas Gloning. De Gruyter, 2010

Julian of Norwich. Revelations of Divine Love. Translated by Barry Windeatt. Oxford University Press, 2015

Karras, Ruth Mazo. Sexuality in Medieval Europe: Doing Unto Others. Routledge, 2017

Kerr, Julie. Monastic Hospitality: The Benedictines in England, c.1070-c.1250. Boydell Press, 2007

Kieckhefer, Richard. Forbidden rites: a necromancer's manual of the fifteenth century. Sutton, 1997

Kümin, Beat and B. Ann Tlusty. The World of the Tavern: Public Houses in Early Modern Europe. Routledge, 2017

Ilner, Thomas, et al. The Economy of Dürnberg-Bei-Hallein: an Iron Age Salt-mining Centre in the Austrian Alps. The Antiquaries Journal, vol. 83, 2003. pp. 123-194

Làng, Benedek. Unlocked Books: Manuscripts of Learned Magic in the Medieval Libraries of Central Europe. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008

Lindeman, Mary. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2010

Lowe, Kate. “'Representing' Africa: Ambassadors and Princes from Christian Africa to Renaissance Italy and Portugal, 1402-1608.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society Sixth Series, vol. 17, pp. 101-128

Meyers, David. “Ritual, Confession, and Religion in Sixteenth-Century Germany.” Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte, vol. 89, 1998. pp. 125-143

Murat, Zuleika. “Wall paintings through the ages: the medieval period (Italy, twelfth to fifteenth century).” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, vol. 12, no. 191. Springer, October 2021. pp. 1-27

Overty, Joanne Filippone. “The Cost of Doing Scribal Business: Prices of Manuscript Books in England, 1300-1483.” Book History 11, 2008. pp. 1-32

Page, Sophie. Magic in the Cloister: Pious Motives, Illicit Interests and Occult Approaches to the Medieval Universe. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013

Park, Katharine. “The Criminal and the Saintly Body: Autopsy and Dissection in Renaissance Italy.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 47, no. 1, Spring 1994. pp. 1-33

Rebel, Hermann. Peasant Classes: The Bureaucratization of Property and Family Relations under Early Habsburg Absolutism, 1511-1636. Princeton University Press, 1983

Rublack, Ulinka. “Pregnancy, Childbirth, and the Female Body in Early Modern Germany.” Past & Present, vol. 150, no. 1, February 1996. pp. 84-110

Salvadore, Matteo. “The Ethiopian Age of Exploration: Prester John's Discovery of Europe, 1306-1458.” Journal of World History, vol. 21, no. 4, 2011. pp. 593 - 627

Sangster, Alan. “The Earliest Known Treatise on Double Entry Bookkeeping by Marino de Raphaeli”. The Accounting Historians Journal, vol. 42, no. 2, 2015. pp. 1-33.

Throop, Priscilla. Hildegard von Bingen's Physica: The Complete English Translation of Her Classic Work on Health and Healing. Healing Arts Press, 1998

Usher, Abbott Payson. “The Origins of Banking: The Primitive Bank of Deposit, 1200-1600.” The Economic History Review, vol. 4, no. 4, 1934. pp. 399-428

Waldman, Louis A. “Commissioning Art in Florence for Matthias Corvinus: The Painter and Agent Alexander Formoser and his Sons, Jacopo and Raffaello del Tedesco.” Italy and Hungary: Humanism and Art in the Early Renaissance. Edited by Péter Farbaky and Louis A. Waldman, Villa I Tatti, 2011. pp. 427-501

Wendt, Ulrich. Kultur und Jagd: ein Birschgang durch die Geschichte. G. Reimer, 1907

Whelan, Mark. “Taxes, Wagenburgs and a Nightingale: The Imperial Abbey of Ellwangen and the Hussite Wars, 1427-1435.” The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, vol. 72, no. 4, 2021, pp. 751-777.e

Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. Women and Gender in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2008

Yardeni, Ada. The Book of Hebrew Script: History, Paleography, Script Styles, Calligraphy & Design. Tyndale House Publishers, 2010

#pentiment#Pentiment bibliography#some of these books give me strong first-year undergrad vibes#even just seeing ulinka rublack’s name gives me semi-traumatic flashbacks to cultural history seminars#would I cope better with it now that I don’t have to write essays each week on the topic?#¯\_ (ツ)_/¯#probs not tbh#also it probably would have been a lot faster if I could have pulled this list from game files somehow#but I do not know how to do that :)))#Anyway I hope this is of use to somebody at some point#I wish you all a very happy reading about the primitive deposit banking system everybody 😌

778 notes

·

View notes

Text

Basawan and Suraj Gujrati. Illustration from Baburnama or Memoirs of Babur, ca. 183-1530.

Baburnama is an autobiographical account by Zahiruddin Muhammad Babur, a descendant of Timur and the first Mughal king of India. The miniatures are from an illustrated copy of the Baburnama prepared for the author's grandson, the Mughal Emperor Akbar. Akbar’s commissions were divided up among teams of artists working at the court, and often two painters collaborated on a single image, in addition to the calligraphers. This particular illustration is attributed to Basawan, responsible for the composition and the drawing, and Suraj Gujarati, who painted it. The miniatures reflect the culture of the Mughal court at Delhi, and are important as evidence of the tradition of exquisite miniature painting which developed at the court of Timur and his successors. Timurid miniatures are among the greatest artistic achievements of the Islamic world in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

#ots#art#babur#baburnama#basawan#suraj gujrati#akbar#mughal art#mughals#medieval art#indian art#miniatures#illustration#mughal empire#indian history

73 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi hallo 👋

Please please please!!! Gush about Vampire!Richard!!! That new photo we got on Sunday was so incredibly sexy and I love hearing your thoughts about Richard!!

Thank yooouuuu ❤️❤️

Hi 👋🏼 (writing prompts incoming I'll never use since well. I'm not a writer yet I have too much imagination for my own good)

Thanks a lot for this ask! A while ago, I got a similar one which got lost on the way into my drafts, so I'm glad I get a second chance to delve into my made up lore for my beloved elderly vampire lord 🦇 So very subjective and personal imaginary facts about vampire!Richard incoming:

Vampire!Richard is an everlasting part of my obsession over him, and 'I'm still alive' really changed my brain chemistry further more in that regard - before it was mostly Völkerball!vampire!Richard, who ruled over my darkest fantasies, drawing me ever deeper into his spell:

In this version, he is in my mind a slightly arrogant but so charming, self-assured young vampire, recklessly spirited and hardly containable, propelled by success, hungry for more - and he fundamentally sees mostly the positive aspects in his immortal existence, which he savors to the fullest extent.

However, at times he falls into melancholic phases, reminiscing about his mortal life and pondering what might have become of him had he not fallen into the clutches of eternal existence.

And yet, I have to admit, with the release of “I'm still alive”, my attention was definitely turned to the senior vampire lord, who immediately captivated me.

Here, Richard strikes me as an educated and worldly gentleman who has a sense of restlessness about him. He appears to have a great demeanor, is confident in himself and knows how charmingly he has to approach people to get what he wants, and yet he carries a certain melancholy with him, some thoughts and memories never seem to quite leave him and which hint at a troubled past. Although he is no longer subconsciously searching for the ultimate sense of immortal life like the young vampire!Richard, he still doesn't seem to be entirely at peace with his past and himself.

Since my brain won't shut up and I had wonderful support by @dandysnob in the quest of working out some thoughts on a background story for elderly vampire lord!Richard a possible origin story for him - of course based entirely subjective on our fantasies around the topic of vampires in general and Richard in this role speficically:

He was born in the late Middle Ages/early Renaissance (around the late fifteenth century) into a fairly well-off, but not overly wealthy family in the northern region of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation - so he had a good start in life, but had to make something of himself to succeed in life.

His ambitious and inquisitive character enabled him to make a name for himself as an intelligent and knowledgable scholar, particularly in the field of art, rare artifacts and, to a certain extent, music research (music was part of the 'septen artes liberales', a canon of seven subjects of study which was very important during which were very important in antiquity and the Middle Ages).

On one of his travels, which led him to the region of Transylvania in Romania due to research on architecture and paintings, something happened that would change Richard's life forever - something he wouldn't have expected at the age of about 50. On the way back from a day trip to the Prejmer fortified church (Church Fortified by Tartlau), his carriage was ambushed on the road through the forest - Richard himself doesn't know exactly what happened, but he woke up after what seemed like a long period of unconsciousness and hasn't been the same since. The changes were gradual - daylight began to blind him unbearably, he became more irritable, had an unbearable hunger, suddenly much sharper senses, and an inexplicable desire to go for the jugular of his fellow human beings.

The following years and decades were difficult for Richard. He distanced himself more and more from his fellow beings and began, through research, to slowly but surely discover what had happened to him. Humanity had less and less space in his life; the vampiric nature gave him a feeling of omnipotence and a hunger that made him completely ruthless towards human life. He deliberately embarked on many journeys to conceal the fact that he no longer aged and to disguise his consumption of humans as a source of sustenance. Changing names became commonplace, and at every university where he began as a scholar, he provided a new name. Thus, he traveled extensively throughout the world, learning more and more about the dark hidden world. Despite the immortality and invulnerability he now enjoyed, Richard was internally torn - on one hand, he managed to keep his private escapades under covers and presented himself outwardly as a distinguished scholar; on the other hand, he missed human life with its true emotions and loved ones deeply.

In the 19th century, he arrived in Victorian London and found his way into high society, moving in similar circles to Lord Byron and his companions. He had always sworn two things to himself: firstly, never to let serious feelings for anyone else arise, as it simply did not fit his lifestyle, and secondly, never to seek victims whose deaths would arouse suspicion - so no woman from the nobility or a similar standing. Until one day, he fell in love with a young woman who was just as enamored with ancient objects, art, and music as he was. Even though he knew this could have no future, he could not resist and courted her, with great success - until one night (she knew of his dark secret and yet loved him deeply) he lost control and accidentally weakened his beloved so much with his thirst for blood that she died in his arms. In her final breaths, she appealed to his humanity, urging him to see that life offers so much if only he allows it.

This experience tore him apart internally, yet it also gave him back the willpower he had lacked for over 300 years. Once again, he swore to leave behind the matter of feelings and emotional relationships, and to exercise more caution, moderation, and compassion - as much as possible as a vampire. After the experience in London with his beloved, he naturally had to leave that place and became restless once again. After further travels, he eventually landed in 21st century New York, where the cultural sector thrived with museums, theaters, film, and music, alongside a flourishing supernatural underworld. Outwardly, he was a successful art dealer, a generous patron of musicians and opera houses, and an expert for museums; secretly, he quickly became known as the most influential and powerful vampire in the city, one best not crossed - a rise akin to Scarface, yet far more sophisticated.

Here we are now - an accomplished man with a successful career, centuries of experience behind him, yet he's filled with melancholy, partial bitterness, constantly struggling with his fate. Whether he will ever find complete fulfillment and happiness again...

a possible continuation can be found in the second part.

#rammstein#richard kruspe#emigrate#ask#vampire#vampire lore#went insane again. well what else is new

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! i loved what you're doing with kc now, can i request something like klaus and caroline doing something mundane and human and we see them living their married couple life? can be a drabble or a full lenth, what ever you want ;p

“Maybe this one?”

“I don’t get it.”

“What’s there not to get?”

“The fabric looks so…dull.”

“It’s supposed to have a shimmering effect in the sunlight.”

“That’ll just remind me of Twilight. No.”

“They're curtains.”

“So?”

Klaus clicks his tongue. “Love—”

“No. No. Do not use that tone with me, Niklaus Mikaelson.”

Ooh. Full named. He’s on thin ice now. “Sweetheart, it’s very simple. It’s a very simple choice, this one or that one.”

“It is so not a simple choice. We’re deciding on curtains for the living room. If you think that’s a simple decision you should just leave right now.”

He reminds himself that answering that is a trap.

Oh, how he wishes he could leave. There’s a new box of paints waiting for him at home, made from shells, a gift from Elijah, and he was hoping to get done with shopping and get home before three, at most.

It’s bloody six and he’s listened to Caroline drone on about stitching patterns for two fucking hours now. One would think they’d be done with the furniture by now, but no. They're just getting started on the upholstery. Heaven forbid Caroline’s exacting tastes allow any of his antique furniture pieces into the living room.

It’s from the fifteenth century, love—

It has clawed feet, Klaus. No.

Sweetheart—

I let you keep the bathtub, but I'm drawing the line on the ottoman. No.

It’s a fine piece—

A tacky one.

Well, I happen to think that of your patio table.

That had been a terribly stupid move.

So now, he’s being punished by being forced to give his opinions on furniture he doesn’t care about. He’s this close to pulling out his hair, and if he sees one more chair with birds on it he’ll be breaking it.

“Caroline—” he whines.

She shuts him up with a glare. “If I wanted to hear whining, I would’ve brought Enzo. Now, opinion.” She holds up two squares of fabric against the light. “Which one?”

Now, see. Klaus is an artist. He prides himself on being one of the best there are, not to brag, but one’s ability is refined after a thousand years. He’s been splashing colours onto surfaces ever since he can remember, the vibrant hues and shades leaving him fascinated since he was a boy. Paints, charcoal, the paint he made from various berries and flowers when he had been human…colours have never left him frazzled.

He knows for sure Caroline’s going to rip off his head when he tells her they’re the exact same colour.

Then he remembers he doesn’t particularly care about his curtains, so he says, “The one on the left.”

Caroline smiles. “There. That wasn’t so hard, was it?”

“Of course not,” he grumbles.

“Hm,” she says distractedly, pressing a quick kiss to his cheek and moving towards the counter. “We’ll get these, then. They’ll go great with your ottoman.”

Klaus’s eyes fly up to meet hers, and she gives him a small smile, one that never fails to leave him reeling. “I'm not a total dictator, you know. I don’t want it to only feel like my home, and not yours. I want it to be ours.”

It’s such a small gesture. In truth, Klaus hadn’t given the ottoman a second thought when they’d had that fight and she’d glared at him angrily and dragged it away to the attic, only focusing on how he could get her in a better mood if only to look at her smile again.

He loves it when she smiles, because oh, her smile is so beautiful. She’s so beautiful.

“Klaus?”

Caroline’s looking at him, her blue eyes concerned. “Are you okay? Did you hear what I said?”

“Yes,” he answers, drawing her in for a kiss. She goes forward with a surprised sound low in her throat, her hands resting on her shoulders. The saleslady clears her throat and Caroline jumps away from him, her face reddening as she turns to her and starts rambling about cushion covers and duvets.

Klaus watches her fondly, all traces of annoyance with her disappearing.

In truth, he’d let her cover the whole house in pink wallpaper if it meant he got to see her laugh every day.

He’d let her do anything, really.

Everything.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sgra-Snyan

Tibetan, 14th–16th century

The ancient "silk route", running from the Mediterranean to Sian in east central China, made Central Asia a meeting place of many cultures. This lute, an extraordinary example of musical exchange between East and West, is similar to instruments played by angels depicted in seventh-century Buddhist cave paintings. It offers some insight into the development of the modern sgra-snyan. The body, with two skin-covered chambers, is a rare example of an archaic transitional form that seems to point to the Afghan robab, and various Himalayan lute types. Decorative elements, such as green-colored skins, like those of the damarn, and the portraits of Buddha and musicians, rendered on painted ivory with gold leaf, are typical of fifteenth-century Tibet. The back, fingerboard, and pegbox reveal cartouches and palmettes reminiscent of seventeenth-century Persia.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite History Books || Triumph and Illusion: The Hundred Years War Volume 5 by Jonathan Sumption ★★★★☆

The wheel of fortune is one of the most ancient symbols of mankind, an image of capricious fate and the transience of human affairs. In the late middle ages it was everywhere, in illuminated manuscripts, in wall paintings and stained glass, in sermons and homilies, in poetry and prose. ‘The wheel of fortune turneth as a ball, sudden climbing axeth a sudden fall,’ wrote John Lydgate in The Fall of Princes, a work commissioned by one of the dominant figures in this history, Cardinal Henry Beaufort. The present volume traces the remarkable recovery of France in barely two decades from the lowest point of its fortunes to the dominant position in Europe which it had enjoyed before the wars with England. Sudden climbing axeth a sudden fall. These years saw the collapse of the English dream of conquest in France from the opening years of the reign of Henry VI, when the battles of Cravant and Verneuil consolidated their control of most of northern France, until the loss of all their continental dominions except Calais. This sudden reversal of fortune, inexplicable to many contemporary Englishmen, was a seminal event in the history of the two principal nation-states of western Europe. It brought an end to four centuries of the English dynasty’s presence in France, separating two countries whose fortunes had once been closely intertwined. It created a new sense of identity in both of them. In large measure, the divergent fortunes of the French and English states over the following centuries flowed from these events.

The passions generated by ancient wars eventually fade, but those provoked by the wars of the English in fifteenth-century France have proved to be surprisingly durable. The foundations of scholarship on the period were laid by patriotic French historians of the nineteenth century, writing under the shadow of Waterloo and Sedan. The passage of the centuries did nothing nothing to soften their indignation about the fate of their country in the time of Henry VI and the Duke of Bedford. The extraordinary life and death of Joan of Arc defied historical objectivity until quite recently. Joan’s story became the focus of disparate but powerful political passions: nationalism, Catholicism, royalism and intermittent anglophobia. Much of what has been written falsifies history by attributing to medieval men and women the notions of another age. But myths are powerful agents of national identity. The great French historian Marc Bloch once wrote that no Frenchman could truly understand his country’s history unless he thrilled at the story of Charles VII’s coronation at Reims. Writing in the summer of 1940 in the aftermath of a terrible defeat, Bloch looked to an earlier recovery from the edge of disaster for reassurance about the survival of France.

If there is a corresponding English myth, it is in the history plays of Shakespeare. The great speeches which he gave to John of Gaunt and Henry V belong to the classic canon of English patriotism. His three plays about Henry VI, a truncated story of discord at home and defeat abroad, never reach the same heights. Yet they serve to remind us that behind the clash of arms and principles were men and women of flesh and blood. I have tried at every page to remember that they were not cardboard cut-outs. They endured hunger, saddle-sores and toothache. They experienced fear and elation, joy and disappointment, shame and pride, ambition and exhaustion. At the level of government, they were trapped by the logic of war, lacking the resources to conquer or even to defend what they had, and yet unable to make peace. It was the tragedy of the English that, after an initial surge of optimism in the 1420s, they realised that the war could not be won, but were forced to fight on by the memory of Henry V’s triumphs and the incapacity of his son, until disaster finally engulfed them.

#litedit#historyedit#hundred years' war#medieval#history books#french history#english history#european history#history#nanshe's graphics

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fetzentödlein, Death in tatters, South German, ca 1670. Boxwood.

Provenance: Germany, Rudolf Theodor Edler von Jaschke Collection (1881–1963).

Representations of skeletal figures were not rare in the Late Middle Ages: personifications of Death as the Grim Reaper with a scythe as his attribute or as an archer in the Dance of Death contexts appeared increasingly from the fifteenth century in frescoes, paintings and reliefs in churches. As a small piece of sculpture of a domestic character, on the other hand, the Fetzentödlein (literally ‘Small Death in tatters’) does not surface until the sixteenth century. The motif is Death depicted fully in the round in a small format as a skeletal figure from which scraps of decayed skin are dangling.

The earliest known work of this kind is a statuette carved before 1519, which is now in the Kunstkammer at Ambras Castle in Innsbruck and is attributed to the Landshut sculptor Hans Leinberger. The type of skeletal figure wearing its decaying skin like a tattered garment would undergo a sharp upturn in popularity in the latter half of the seventeenth century: several statuettes of this kind are kept by public and private collections, including the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in Munich, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, and the Busch-Reisinger Museum, which is part of the Harvard University Art Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This small group of works is stylistically and structurally homogeneous, and dated to ca 1670 because the work in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum bears the date numerals 1673 on its plinth. A pronounced delight in morbid details is flaunted in this small statue: decaying skin detaches itself from the cranial bones like a hood and encases the figure’s feet like decrepit old shoes; the abdominal wall gapes open to reveal the entrails, some of which bulge out and are crawling with vermin. The deliberately gruesome mode of representation contrasts with the virtuosity of execution that marks this boxwood statuette as an exquisite work of art.

Courtesy Alain Truong

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ganjifa, a Persian card game that has been popular in the Indian subcontinent since the sixteenth century, is notable for its hand-painted playing cards. The name Ganjifa likely derives from the Persian word ganj, meaning treasure or money. The game has several variations across West, Central and South Asia.

The oldest surviving reference to Ganjifa in India was made in the early fifteenth century by the historian Ibn Taghribirdi, who wrote that a Mamluk sultan gambled with kanjifa (a medieval Arabic name for Ganjifa) as a young man.

#hindu mythology#mythology#19th century#literature#modern art#museums#ancient persia#card game art#mythoprofessori

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The new humanism that arose from the rediscovery of the ancient knowledge and literature would in turn give rise to the Renaissance, which began as a 'rebirth' but would soon evolve an originality of its own. There is one crucial aspect that links this long and gradual process, which would come to full flowering as the fifteenth century progressed. This aspect is knowledge—the early humanists rediscovered it, and the Renaissance artists saw themselves as extending it. The most characteristic and original expression of the Renaissance would be its art, yet crucially its artists saw this activity as a form of learning; and here at least, the passage from humanism to the Renaissance is all but seamless.

The Renaissance artists would paint images of a visibly different humanity from that depicted in the religious paintings of their medieval predecessors. This was achieved by shedding previous stylization and formalism, and although much of the medieval religious symbolism would be retained, this would increasingly be tempered by the artist imbuing his figures with an element of psychological realism. Human beings would be depicted with all the verisimilitude of a classical statue, usually placed in a recognizable landscape. Although the subjects remained for the most part religious (saints, the Madonna, biblical scenes and so forth), these holy figures were seen less as transcendental or metaphysical figures and more as they might have lived in the reality of their human lifetime. Art would become a form of learning about what a human being was, of understanding the purely human condition; this new art would seen to teach man about himself, and his world, in an almost scientific manner—indeed it would, in many ways, aspire to be a science. {...} Renaissance artists, such as Leonardo Da Vinci, would even use their art to depict the secrets of nature, and of human nature—drawing the intricacies of flowing water, human anatomy, as well as imagined or invented complex mechanical objects. It is important to remember that this aspect of art as a form of knowledge was always an integral part of enterprise; from the outset, Renaissance artists saw themselves as discovering new truths—about art, about technique, about humanity and the world."

— Paul Strathern, The Medici

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dorset churches: Puddletown

Puddletown church gives a good impression of what churches would have looked like in the seventeenth century. It was refurbished in 1635 following a visitation by Archbishop Laud: gallery, box pews, pulpit, reading desk, three-sided altar rails and font cover all date from the seventeenth-century.

The gallery has this inscription:

This translates as: 'you are here not to be looked at but to listen and pray’. There were contemporary complaints that people came to church to look and be looked at, that they cared more for showing their respects to their ‘betters’, than showing due reverence to God; the Directory for Publick Worship (1645) advises the congregation against ‘doing reverence to any persons present, or comming in’ along with ‘private whisperings’, ‘conferences’ and ‘salutations'. Due reverence would have involved taking your hat off; the pegs you can see attached above the pews were to hang them on.

Painted texts (recently restored) are also seventeenth century:

Civil war bullets were found embedded in one of the doors, and are on display in the church near a fine set of medieval monuments, including one to Thomas Martyn bearing the monkey emblem of the Martyn family of nearby Athelhampton manor, dating from the late fifteenth century.

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Daily Don]

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

AUG 30, 2023

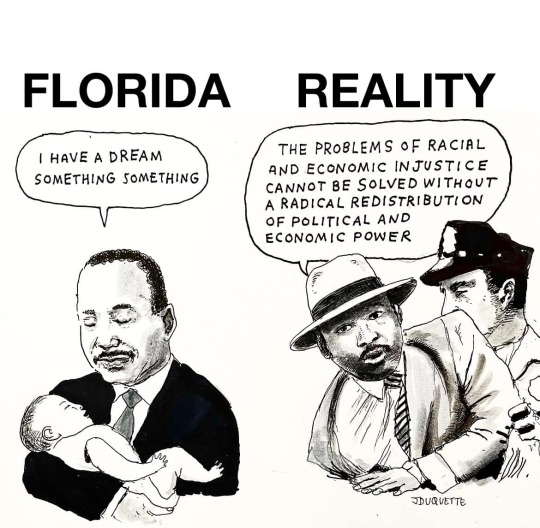

Four days ago, on Saturday, August 26, in the early afternoon, a heavily armed, 21-year-old white supremacist in a tactical vest and mask, who had written a number of racist manifestos and had swastikas painted on his rifle, murdered three Black Americans at a Dollar General store in Jacksonville, Florida. He had apparently intended to attack Edward Waters University, a historically Black institution, but students who saw him put on tactical gear warned a security guard, who chased him off and alerted a sheriff’s deputy.

As David Kurtz of Talking Points Memo put it two days later, “America is living through a reign of white supremacist terror,” and in a speech to the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under the Law on Monday, President Joe Biden reminded listeners that “the U.S. intelligence community has determined that domestic terrorism, rooted in white supremacy, is the greatest terrorist threat we face in the homeland—the greatest threat.”

Biden said he has made it a point to make “clear that America is the most multiracial, most dynamic nation in the history of the world.” He noted that he had nominated the first Black woman, Ketanji Brown Jackson, for the Supreme Court and has put more Black women on the federal circuit courts than every other U.S. president combined. Under him, Congress has protected interracial and same-sex marriages, and his administration has more women than men. He warned that “hate never dies. It just hides.”

But in his Editorial Board newsletter, John Stoehr pointed out that the increasing violence of white supremacists isn’t just about an “ideology of hate” rising, but it is “about a minority faction of the country going to war, literal war, with a majority faction.” He pointed to former governor of Alaska Sarah Palin’s recent prediction of civil war because “We’re not going to keep putting up with this…. We do need to rise up and take our country back.” Stoehr calls these white supremacists “Realamericans” who believe they should rule and, if they can’t do so lawfully, believe they are justified in taking the law into their own hands.

Indeed, today’s white supremacist violence has everything to do with the 1965 Voting Rights Act that protected the right to vote guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1870 after white supremacists refused to recognize the right of Black Americans to vote and hold office. Minority voting means a government—and a country—that white men don’t dominate.

In the 1870s, once the federal government began to prosecute those white men attacking their Black neighbors for exercising their right to vote, white supremacists immediately began to say that they had no issues with Black voting on grounds of race. Their issue, they said, was that Black men were poor, and they were voting for lawmakers—some Black but primarily white—who supported the construction of roads, schools, hospitals, and so on. While these investments were crucial in the devastated South and would help white Americans as well as Black ones, white supremacists insisted that such government action redistributed wealth from white people to Black people and thus was a form of socialism.

It was a short step from this argument to insisting that Black men shouldn’t vote because they were “corrupting” the American system. By 1876, former Confederates had regained control of southern state legislatures, where they rewrote voting laws to exclude Black men and people of color on grounds other than that of race, which the Fifteenth Amendment had made unconstitutional.

By the end of the nineteenth century, white southerners greeted any attempt to protect Black voting as an attempt to destroy true America. Finally, in North Carolina in 1898, Democrats recognized they were losing ground to a biracial fusion ticket of Republicans and Populists who promised economic and political reforms. Before that year’s election, white Democratic leaders ran a viciously racist campaign to fire up their white base. “It is time for the oft quoted shotgun to play a part, and an active one,” one woman wrote, ”in the elections.”

Blocking Fusion voters from the polls and threatening them with guns gave the Democrats a victory, but in Wilmington the biracial city government had not been up for reelection and so remained in power. Vigilantes said they would never again be ruled by Black men and their unscrupulous white allies who intended to “dominate the intelligent and thrifty element in the community.” They destroyed Black businesses and property and killed as many as 300 Black Americans, then portrayed themselves as reluctant victims who had been obliged to remove inefficient and stupid officials before they reduced the city to further chaos.

In 2005, white supremacists in North Carolina echoed this version of the Wilmington coup, claiming it was a natural reaction to “oppressive radical social policies” and a “carnival of corruption and criminality” by their opponents, who used the votes of ignorant Black men to stay in power.

That echo is no accident. The 1965 Voting Rights Act ended the power of white supremacists in the Democratic Party once and for all, and they switched to the Republicans. Then-Democratic South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond had launched the longest filibuster in U.S. history to try to stop the 1957 Civil Rights Act; Republican candidate Richard Nixon deliberately courted him and those who thought like him in 1968.

Republicans adopted the same pattern Democrats had used in the late nineteenth century, claiming their concerns were about taxes and government corruption, pushing voter suppression legislation by insisting they cared about “voter fraud,” insisting their opponents were un-American socialists attempting to overthrow a fairly-elected government.

This political side of white supremacy is all around us. As Democracy Docket put it last month, “Republicans have a math problem, and they know it. Regardless of their candidate, it is nearly certain that more people will vote to reelect Joe Biden than his [Republican] opponent.” After all, Democrats have won the popular vote since 2008. Under these circumstances and unwilling to moderate their platform, “Republicans need to make it harder to vote and easier to cheat.”

Republican-dominated state legislatures are working to make it as hard as possible for minorities and younger Americans to vote, while also pushing the election denier movement to undermine the counting and certification of election results. At the same time, eight Republican-dominated states have left the nonpartisan Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC), a compact between the states that makes it easier to share voter information to avoid duplicate registration and voting, and three more are considering leaving.

In a special session of the Tennessee legislature this week, Republican lawmakers blocked the public from holding signs (a judge blocked the rule), kicked the public out of a hearing, and passed new rules that could prohibit Democrats from speaking. House speaker Cameron Sexton silenced young Black Democratic representative Justin Jones for a day and today suggested the Republicans might make the rule silencing minority members permanent.

In Wisconsin, where one of the nation’s most extreme gerrymanders gives Republicans dominance in the legislature, Republicans in 2018 stripped Democratic governor-elect Tony Evers of power before they left office, and now right-wing Chief Justice Annette Ziegler has told the liberal majority on the state supreme court that it is staging a “coup” by exercising their new power after voters elected Justice Janet Protasiewicz to the court by a large majority in April. Now the legislature is talking about keeping the majority from getting rid of the gerrymandered maps by impeaching Protasiewicz.

The courts are trying to hold the line against this movement. In Washington, D.C., today, U.S. District Court Judge Beryl Howell decided in favor of Black election workers Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss, who claimed that Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani defamed them when he claimed they had committed voter fraud. Not only did Howell award the two women court costs and damages, she called out Giuliani and his associates for trying to keep their records hidden.

But as the courts are trying to hold the line, its supporters are targeting the courts themselves, with MAGA Republicans threatening to defund state and federal prosecutors they claim are targeting Republicans, and announcing their intention to gather the power of the Department of Justice into their own hands should they win office in 2024.

After pushing a social studies curriculum that erases Black agency and resistance to white supremacy, Florida governor Ron DeSantis on Monday suggested the Jacksonville shooting was an isolated incident.

The Black audience booed.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Letters From An American#Heather Cox Richardson#history#racism#voting#US History#white supremisist terrorism#white supremism

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

MWW Artwork of the Day (4/17/24)

Late Medieval England (14th-15th c.)

Resurrection (c. 1450-90)

Alabaster sculpture, with traces of paint, 49.5 x 27.9 x 5.9 cm.

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore MD

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, alabaster was a popular sculptural material in England, where it was in plentiful supply. This dramatic panel showing the moment of Christ's Resurrection exemplifies the detail and texture that could be achieved by sculptors working in alabaster. In this exquisitely refined carving, even very shallow relief can suggest a decided sense of depth by depicting overlapping forms. The soldiers in front are in front of the open tomb, which is in front of other sleeping soldiers. The figure of the risen Christ is carved with such subtlety that even the fabric of his mantle appears soft. As Christ steps from the tomb, his foot rests so gently on the sleeping soldier that he doesn't even wake.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Garden of Earthly Delights (1500-1505)

🎨 Hieronymus van Aken aka Bosch

🏛️ Museo del Prado

📍 Madrid, Spain

The Garden of Earthly Delights is Bosch’s most complex and enigmatic creation. For Falkenburg the overall theme of The Garden of Earthly Delights is the fate of humanity, as in The Haywain (P02052), although Bosch visualizes this concept very differently and in a much more explicit manner in the centre panel of that triptych than in The Garden of Earthly Delights. In order to analyse the work’s meaning the content of each panel must be identified. On the outer faces of the triptych Bosch depicted in grisaille the Third Day of the Creation of the World, when the waters were separated from the earth and the earthly Paradise (Eden) created. At the top left we see God the Father as the Creator, according to two Latin inscriptions, one on each panel: For he spake, and it was done and For he commanded, and they were created (Psalms 33:9 and 148:5). On the inner face of the triptych, painted in brilliant colours which contrast with the grisaille, Bosch painted three scenes that share the single common denominator of the concept of sin, which starts in Paradise or Eden on the left panel, with Adam and Eve, and is punished in Hell in the right panel. The centre panel depicts a Paradise that deceives the senses, a false Paradise given over to the sin of lust. This deception is encouraged by the fact that the centre panel is shown as a continuation of Eden through the use of a single, continuous landscape with a high horizon line that allows for a broad, panoramic composition arranged as three superimposed planes, in the panels of the earthly Paradise, the Garden of Earthly Delights and Hell.

While sin is the connecting link between the three scenes, the iconography in the Paradise panel requires further analysis in order fully to appreciate its meaning. As will be noted below in the analysis of the technical documentation, when he initially embarked on the work Bosch included the Creation of Eve on the left panel, but in a second phase he replaced it with God presenting Eve to Adam. This very uncommon subject was associated with the institution of marriage, as Falkenburg and Vandenbroeck discuss (Bosch, 2016). For the latter, the centre panel represents the false paradise of love, known as Grail in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, which implied a carnal interpretation of God’s mandate to Be fruitful and multiply, as instituted in marriage. The men and women that Bosch depicts in the Garden of Earthly Delights believe they are inhabiting a paradise for lovers, but this is false and their only fate is punishment in Hell. The extremely pessimistic message that the centre panel conveys is that of the fragility and ephemeral nature of happiness and delight in these sinful pleasures.

In the centre panel, from which the triptych derives its name, Bosch included a large number of naked human figures, with the exception of the pair at the lower right, who are usually identified as Adam and Eve after the Expulsion from Paradise. Men and women, both black and white, are generally seen in groups or pairs, maintaining amorous relations with a powerful erotic charge that refers to the panel’s pre-eminent theme, the sin of lust. The animals, both real and imaginary, are much larger than their proper scale. Among them, Bosch particularly emphasizes two different types of owl that evoke evil. Staring straight out, they direct their disturbing gazes at the viewer at the two lateral edges of the panel, slightly set back from the immediate foreground. Also present are plants and fruit, which are again much larger than their scale dimensions. The entire composition is dotted with pieces of red fruit that contrast with other large and small blue ones, these being the two principal colours in the scene. In contrast to the apparent confusion that prevails in the foreground, geometry imposes itself in the middle ground and background. In the former, Bosch depicted a pool full of naked women. Around it, in an anti-clockwise direction, rides a group of men on different mounts (some of them exotic or imaginary), who have been associated with different Cardinal Sins. In the background of the scene Bosch included five fantastical architectural constructions in the water, the central one similar to the fountain of the Four Rivers in the Paradise panel, although here broken to symbolize its fragility and the ephemeral nature of the delights being enjoyed by the men and women who fill this garden. And now the owl depicted inside the fountain in the Paradise panel is replaced here by human figures in sexually explicit poses.

The right panel depicts Hell and is Bosch’s most striking representation of this subject, on occasions referred to as the musical Hell owing to the significant presence of instruments used to torture sinners who have devoted their time to secular music. In his text in the present catalogue Larry Silver describes the punishments meted out to each sin. While lust prevails in the centre panel, in the scene of Hell all the Cardinal Sins are punished. A good example is the punishment of the avaricious, who are devoured and immediately expelled from the anus of a theriomorphic creature with a bird’s head (a variety of owl) seated on a type of child’s lavatory stool. Gluttons and the sin of gluttony are undoubtedly referred to in the tavern scene located inside the tree-man, in which semi-naked people seated at a table wait to be served toads and other unpleasant creatures by devils, while the envious are tortured by immersion in frozen water. Further punishments correspond to vices censured by society at the time, including board games, while particular social classes are also singled out, including the clergy, who were notably criticized at this period, as reflected in the pig wearing a nun’s veil embracing a naked man in the lower right corner.

Although the triptych in the Museo del Prado is not signed, its attribution to Bosch has never been doubted. Its dating, however, is the subject of considerable debate. The results of the dendrochronological analyses could allow it to be located within the early years of the artist’s activity, around 1480-85, as Vermet stated without any supporting evidence. However, the work’s stylistic proximity to the Adoration of the Magi Triptych in the Prado (P02048), which can be securely dated to 1494 following Duquenne’s identification in 2004 of the donors, Peeter Scheyfve and Agneese de Gramme from Antwerp, confirms that the present work must have been painted in the 1490s and not after 1505, as most authors preferred to believe prior to Duquenne’s discovery. It has recently been argued that it must have been painted in or after 1494 as the image of God the Father creating the world on the reverse of the triptych is inspired by a print by Michel Wolgemut of the same subject -including the same text from the Psalms as appears on the wings- which appeared in Hartman Schedelsche Weltchronik published in Nuremberg in 1493.

Research undertaken in 1967 by Gombrich and Steppe allowed The Garden of Earthly Delights to be associated with the Nassau family. An account by Antonio de Beatis, who accompanied Cardinal Luis de Aragon as his secretary on his trip to the Low Countries, states that on 30 July 1517 the triptych was in the Nassau palace of Coudenberg in Brussels, where De Beatis presumably saw it. Since in the late 1960s the painting was considered to be a late work by Bosch, executed after the death of Engelbert’s II of Nassau in 1504, it was therefore thought that the patron was Henry III of Nassau (1483-1538), Engelbert nephew and heir. In the present day and in the light of the information that locates the triptych in the 1490s, it can be confirmed that it was commissioned from Bosch by Engelbert, who must have intended it for the Coudenberg Palace.

#The Garden of Earthly Delights#Hieronymus van Aken aka Bosch#painting#Brussels#Belgium#Hieronymus Bosch#oil on panel#oil painting#oil on oak panel#triptych#oak#Renaissance#dutch#Madrid#Spain#Museo del Prado

9 notes

·

View notes