#general miltiades

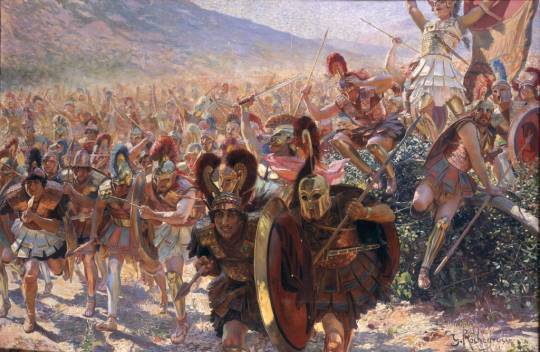

Photo

Battle of Marathon: The Helmet With the Soldier’s Skull Still Inside

This remarkable Corinthian-style helmet from the Battle of Marathon was reputedly found in 1834 with a human skull still inside.

It now forms part of the Royal Ontario Museum’s collections, but originally it was discovered by George Nugent-Grenville, who was the British High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands between 1832-35.

A keen antiquarian, Nugent-Grenville carried out a number of rudimentary archaeological excavations in Greece, one of which took place on the Plains of Marathon, where the helmet was uncovered.

A pivotal moment in Ancient Greek history, the battle of Marathon saw a smaller Greek force, mainly made up of Athenian troops, defeat an invading Persian army.

There were numerous casualties, and it appears that this helmet belonged to a Greek hoplite (soldier) who died during the fighting of the fierce and bloody battle.

The Athenian army under General Miltiades consisted almost entirely of hoplites in bronze armor, using primarily spears and large bronze shields. They fought in tight formations called phalanxes and literally slaughtered the lightly-clad Persian infantry in close combat.

The hoplite style of fighting would go on to epitomize ancient Greek warfare.

Today the helmet and associated skull can be viewed at the Royal Ontario Museum’s Gallery of Greece.

Battle of Marathon saved Western Civilization

It was in September of the year 490 BC when, just 42 kilometers (26 miles) outside of Athens, a vastly outnumbered army of brave soldiers saved their city from the invading Persian army in the Battle of Marathon.

But as the course of history shows, in the Battle of Marathon, they saved more than just their own city: they saved Athenian democracy itself, and consequently, protected the course of Western civilization.

According to historian Richard Billows and his well-researched book Marathon: How One Battle Changed Western Civilization, in one single day in 490 BC, the Athenian army under General Miltiades changed the course of civilization.

It is very unlikely that world civilization would be the same today if the Persians had defeated the Athenians at Marathon. The mighty army of Darius I would have conquered Athens and established Persian rule there, putting an end to the newborn Athenian democracy of Pericles.

In effect, this would certainly have destroyed the idea of democracy as it had developed in Athens at the time.

The Battle of Marathon lasted only two hours, ending with the Persian army breaking in panic toward their ships with the Athenians continuing to slay them as they fled.

In his book, however, Billows calls the Battle of Marathon a “miraculous victory” for the Greeks. The victory was not as easy as it is often portrayed by many historians. After all, the Persian army had never before been defeated.

By Tasos Kokkinidis.

#Battle of Marathon: The Helmet With the Soldier’s Skull Still Inside#greek helmet#persian army#general miltiades#king darius i#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history#long reads

88 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Miltiades (c.550 BCE - 489 BCE)

Miltiades was an Athenian general, known for his decisive role at the Battle of Marathon and for his fall from power shortly after. A smart man, a military genius who bears an awesome beard and an equally awesome helmet. What's not to like about him?

151 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just found your Minor Interference au and I've been reading up on it so sorry if this has been asked before but, will the boys ever get to know what names Draxum originally was going to give them had he been the one to raise them?

And if they won't can We know what they are?

I've been debating revealing them or not, but since if they show up in the fic at all it's gonna be quite some time, I might as well show my hand.

Leo: Lua. In several cultures it is associated with the moon, nature, and celestial beauty. It was also the name of a Roman goddess to whom soldiers would sacrifice the weapons they captured in battle. (Also the name I gave Draxum's mom in my lore lol)

Raph: Ragnarok. The end of the world in Norse mythology, a great battle that would destroy the gods, cause natural disasters, and bring about a new age.

Donnie: Demophon. The name means voice of the people. One of the warriors from the Trojan War who successfully made it back home, at least in some versions of Greek myths. He was also one of the first kings of Athens and possibly established its court system.

Mikey: Miltiades. Means red earth. Historically, it was the name of the general whose tactics allowed the Greeks to win the battle of Marathon against the Persians, a turning point in the Greco-Persian wars.

So as you can see, there's a bit of a theme here. The names that Draxum picked out for them, just on history alone, have strong associations with war and destruction. His original plan would have been to raise them as soldiers from the start, and these names reflect that. They were named for the task they were created to carry out: the annihilation of humans.

As a side note, Draxum picking out flower nicknames for them now isn't just about him figuring out what to call them. It's also about him getting a second chance to name them, as the people they are and not the people he wanted them to be.

#asks#rottmnt#rottmnt au#minor interference au#minor interference lore#rottmnt draxum#these are the names they'd go by if i ever got around to writing my 'draxum raised the turtles' au lol#but yeah draxum would have put a ton of thought and research into picking out names for his turtles (which was before their mutation btw)#which ties into my idea that even if he'd raised them he would not have gotten soldiers out of it. he'd have gotten four kids#like he was emotionally attached to them even before he mutated them to the point that he was making them cute little outfits#MI!draxum was Ready to be a dad lmao#bambi's rambling

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Greece and Ancient Iran: Cross‐Cultural Encounters

1st INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE (ATHENS, 11‐13 NOVEMBER 2006)

Edited by Seyed Mohammad Reza Darbandi and Antigoni Zournatzi

National Hellenic Research Foundation

Cultural Center of the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran in

Athens

Hellenic National Commission for UNESCO

Athens, December 2008

Description

The extraordinary feats of conquest of Cyrus the Great and Alexander the Great have left a lasting imprint in the annals of world

history. Successive Persian and Greek rule over vast stretches of territory from the Indus to the eastern Mediterranean also created an

international environment in which people, commodities, technological innovations, as well as intellectual, political, and artistic ideas could circulate across the ancient world unhindered by ethno-cultural and territorial barriers, bringing about cross-fertilization between East and West. These broad patterns of cultural phenomena are illustrated in twenty-four contributions to the first international conference on ancient Greek-Iranian interactions, which was organized as a joint Greek and Iranian initiative.

Contents

Preface (Ekaterini Tzitzikosta)

Conference addresses (Dimitrios A. Kyriakidis, Seyed Taha Hashemi Toghraljerdi, Mir Jalaleddin Kazzazi, Vassos Karageorghis,

Miltiades Hatzopoulos, Seyed Mohammad Reza Darbandi, Massoud Azarnoush, David Stronach)

Introduction (Seyed Mohammad Reza Darbandi and Antigoni Zournatzi)

Europe and Asia: Aeschylus’ Persians and Homer’s Iliad (Stephen Tracy)

The death of Masistios and the mourning for his loss (Hdt. 9.20-25.1) (Angeliki Petropoulou)

Magi in Athens in the fifth century BC? (Kyriakos Tsantsanoglou)

Hājīābād and the dialogue of civilizations (Massoud Azarnoush)

Zoroastrianism and Christianity in the Sasanian empire (fourth century AD) (Sara Alinia)

Greco-Persian literary interactions in classical Persian literature (Evangelos Venetis)

Pseudo-Aristotelian politics and theology in universal Islam (Garth Fowden)

The system Artaphernes-Mardonius as an example of imperial nostalgia (Michael N. Weiskopf)

Greeks and Iranians in the Cimmerian Bosporus in the second/first century BC: new epigraphic data from Tanais (Askold I.

Ivantchik)

The Seleucids and their Achaemenid predecessors: a Persian inheritance? (Christopher Tuplin)

Managing an empire — teacher and pupil (G. G. Aperghis)

The building program of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae and the date of the fall of Sardis (David Stronach)

Persia and Greece: the role of cultural interactions in the architecture of Persepolis— Pasargadae (Mohammad Hassan Talebian)

Reading Persepolis in Greek— Part Two: marriage metaphors and unmanly virtues (Margaret C. Root)

The marble of the Penelope from Persepolis and its historical implications (Olga Palagia)

Cultural interconnections in the Achaemenid West: a few reflections on the testimony of the Cypriot archaeological record

(Antigoni Zournatzi)

Greek, Anatolian, and Persian iconography in Asia Minor: material sources, method, and perspectives (Yannick Lintz)

Imaging a tomb chamber: the iconographic program of the Tatarlı wall paintings (Lâtife Summerer). Appendix: Tatarli Project:

reconstructing a wooden tomb chamber (Alexander von Kienlin)

The Achaemenid lion-griffin on a Macedonian tomb painting and on a Sicyonian mosaic (Stavros A. Paspalas)

Psychotropic plants on Achaemenid style vessels (Despina Ignatiadou)

Achaemenid toreutics in the Greek periphery (Athanasios Sideris)

Achaemenid influences on Rhodian minor arts and crafts (Pavlos Triantafyllidis)

Historical Iranian and Greek relations in retrospect (Mehdi Rahbar)

Persia and Greece: a forgotten history of cultural relations (Shahrokh Razmjou)

The editors

Seyed Mohammad Reza Darbandi is General Director of Cultural Offices of the Islamic Republic of Iran for Europe and the Americas.

Antigoni Zournatzi is Senior Researcher in the Research Centre for Greek and Roman Antiquity, National Hellenic Research

Foundation. Her work focuses on the relations between Achaemenid Persia and the West.

The whole volume can be found as pdf on:

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greek Bronze Corinthian Type - "Helmet of Miltiades" the Athenian General who defeated the Persians at the Battle of Marathon in 490

ВС.

The inscription on the lip of the helmet cheek section reads in Greek "Miltiades dedicated to Zeus".

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Greeks preserve the bridge of Darius by John Steeple Davis 1900

"They then sent the division of the Scythians to which the Sauromatae were attached, and which was led by Scopasis, to speak with those Ionians guarding the bridge over the Ister; as for those of the Scythians who remained behind, it was decided that they should no longer decoy the Persians, but attack them whenever they were foraging for provision. So they watched for the time when Darius' men were foraging, and did as they had planned.

When the first division of the Scythians came to the bridge—the division that had first been appointed to stand on guard by the Maeetian lake and had now been sent to the Ister to speak with the Ionians—they said, “Ionians, we have come to bring you freedom, if you will only listen to us. We understand that Darius has directed you to guard the bridge for sixty days only, and if he does not come within that time, then to go away to your homes. Now then, do what will leave you guiltless in his eyes as in ours: stay here for the time appointed; and after that, leave.” So the Ionians promised to do this, and the Scythians made their way back with all haste.

...

And as the Persian army was for the most part infantry and did not know the roads (which were not marked), while the Scythians were horsemen and knew the short cuts, they went wide of each other, and the Scythians reached the bridge long before the Persians.

There, perceiving that the Persians had not yet come, they said to the Ionians, who were in their ships, “Ionians, the days have exceeded the number, and you are wrong to be here still.

Since it was fear that kept you here, now break the bridge in haste and go, free and happy men, thanking the Gods and the Scythians. As for him that was once your master, we will leave him in such plight that never again will he lead his army against any nation.”

Then the Ionians held a council. Miltiades the Athenian, general and sovereign of the Chersonesites of the Hellespont, advised that they do as the Scythians said and set Ionia free.

But Histiaeus of Miletus advised the opposite. He said, “It is owing to Darius that each of us is sovereign of his city; if Darius' power is overthrown, we shall no longer be able to rule, I in Miletus or any of you elsewhere; for all the cities will choose democracy rather than despotism.”

When Histiaeus explained this, all of them at once inclined to his view, although they had first sided with Miltiades.

Those high in Darius' favor who gave their vote were Daphnis of Abydos, Hippoclus of Lampsacus, Herophantus of Parium, Metrodorus of Proconnesus, Aristagoras of Cyzicus, Ariston of Byzantium, all from the Hellespont and sovereigns of cities there; and from Ionia, Strattis of Chios, Aiaces of Samos, Laodamas of Phocaea, and Histiaeus of Miletus who opposed the plan of Miltiades. As for the Aeolians, their only notable man present was Aristagoras of Cymae.

When these accepted Histiaeus' view, they decided to act upon it in the following way: to break as much of the bridge on the Scythian side as a bowshot from there carried, so that they seem to be doing something when in fact they were doing nothing, and that the Scythians not try to force their way across the bridge over the Ister; and to say while they were breaking the portion of the bridge on the Scythian side, that they would do all that the Scythians desired.

This was the plan they adopted; and then Histiaeus answered for them all, and said, “You have come with good advice, Scythians, and your urgency is timely: you guide us well and we do you a convenient service; for, as you see, we are breaking the bridge, and will be diligent about it, as we want to be free.

But while we are breaking the bridge, this is your opportunity to go and find the Persians, and when you have found them, punish them as they deserve on our behalf and on your own.”

So the Scythians, trusting the Ionians' word once more, turned back to look for the Persians; but they missed the way by which their enemies returned. The Scythians themselves were to blame for this, because they had destroyed the horses' pasturage in that region and blocked the wells.

Had they not done, they could, if they had wished, easily have found the Persians. But as it was, that part of their plan which they had thought the best was the very cause of their going astray."

-Herodotus, The Histories, Book 4.128-140

#scythian#ancient greece#persian history#history#ancient history#darius the great#book art#literature#herodotus#20th century art#art#john steeple davis

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Demosthenes the Athenian General - a Few Notes

I don't know if anyone cares, but - there's so little out there about Demosthenes' background and life outside of his actions during the Arkhidamian War that I thought it might be worth sharing what I've learnt recently.

It's only because I'm currently researching the lives of both Demosthenes (the orator makes my research life so freaking vexed) and Thucydides the historian that I stumbled across the interesting tit-bit that there's a possible familial connection between them.

I've spent some time since tracing down the actual source for this belief and this is the footnote that is most often referenced:

‘He [Thucydides] may even have been connected to Demosthenes by marriage, since a "Θουκυδίδης Ἀλκισθένους Ἀφιδναῖος· [Thucydides Alkisthenous Aphidnaios]" (the patronymic [Alkisthenous] and deme [Aphidnaios] are the same as those of Demosthenes) is attested in an inscription from the second half of the fourth century.'

[From Individuals in Thucydides by HD Westlake, p.97.]

This is the specific inscription: IG ii2 1678. Line 31. I couldn't find a translation of the whole inscription, so I remain uncertain what this document actually is.

If we follow this lead, and assume that Demosthenes was related to Thucydides, then we can perhaps add some interesting, Thracian, flavour to his background.

Kimon's father was Miltiades, but his mother, Hegesipyle, was a Thracian by birth, the daughter of Kong Oloros, as we read in the poems of Archelaus and Melanthius addressed to Kimon himself. This also explains why the father of Thucydides the historian, who was related by birth to Kimon's family, was called Oloros, since the father took the name from the ancestor, and owned gold-mines in Thrace. He is said to have died there too, murdered in a place called Scapte Hyle, but his remains were brough back to Attika and one is shown his tombstone in the Kimoneia alongside the grave of Kimon's sister, Elpenike. Thucydides however was from the deme Halimus, while Miltiades was from Laciadae.

[Plutarch, Life of Kimon. 4]

I have much further to go with all this (everything - the thinking, the ever enlarging sea of things I don't know, the things I should read, the facts or theories I need to process...) - but these two excerpts already suggest interesting perspectives to me - especially around Thucydides' approach to/ writings about Demosthenes' career (which is a whole thing that is blowing my mind lately); but also Thucydides' connection to Thrace/the north, and how that might have affected his feelings at Eion when he was facing Brasidas.

May the gods grant me enough years.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 1.31 (before 1945)

314 – Pope Sylvester I is consecrated, as successor to the late Pope Miltiades.

1208 – The Battle of Lena takes place between King Sverker II of Sweden and his rival, Prince Eric, whose victory puts him on the throne as King Eric X of Sweden.

1504 – The Treaty of Lyon ends the Italian War, confirming French domination of northern Italy, while Spain receives the Kingdom of Naples.

1578 – Eighty Years' War and Anglo-Spanish War: The Battle of Gembloux is a victory for Spanish forces led by Don John of Austria over a rebel army of Dutch, Flemish, English, Scottish, German, French and Walloons.

1606 – Gunpowder Plot: Four of the conspirators, including Guy Fawkes, are executed for treason by hanging, drawing and quartering, for plotting against Parliament and King James.

1609 – Wisselbank of Amsterdam established

1747 – The first venereal diseases clinic opens at London Lock Hospital.

1814 – Gervasio Antonio de Posadas becomes Supreme Director of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (present-day Argentina).

1846 – After the Milwaukee Bridge War, the United States towns of Juneautown and Kilbourntown unify to create the City of Milwaukee.

1848 – John C. Frémont is court-martialed for mutiny and disobeying orders.

1862 – Alvan Graham Clark discovers the white dwarf star Sirius B, a companion of Sirius, through an 18.5-inch (47 cm) telescope now located at Northwestern University.

1865 – American Civil War: The United States Congress passes the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, abolishing slavery, and submits it to the states for ratification.

1865 – American Civil War: Confederate General Robert E. Lee becomes general-in-chief of all Confederate armies.

1891 – History of Portugal: The first attempt at a Portuguese republican revolution breaks out in the northern city of Porto.

1900 – Datu Muhammad Salleh is killed in Kampung Teboh, Tambunan, ending the Mat Salleh Rebellion.

1901 – Anton Chekhov's Three Sisters premieres at Moscow Art Theatre in Russia.

1915 – World War I: Germany is the first to make large-scale use of poison gas in warfare in the Battle of Bolimów against Russia.

1917 – World War I: Kaiser Wilhelm II orders the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare.

1918 – A series of accidental collisions on a misty Scottish night leads to the loss of two Royal Navy submarines with over a hundred lives, and damage to another five British warships.

1918 – Finnish Civil War: The Suinula massacre, which changes the nature of the war in a more hostile direction, takes place in Kangasala.

1919 – The Battle of George Square takes place in Glasgow, Scotland, during a campaign for shorter working hours.

1928 – Leon Trotsky is exiled to Alma-Ata.

1942 – World War II: Allied forces are defeated by the Japanese at the Battle of Malaya and retreat to Singapore.

1943 – World War II: German field marshal Friedrich Paulus surrenders to the Soviets at Stalingrad, followed two days later by the remainder of his Sixth Army, ending one of the war's fiercest battles.

1944 – World War II: American forces land on Kwajalein Atoll and other islands in the Japanese-held Marshall Islands.

1944 – World War II: During the Anzio campaign, the 1st Ranger Battalion (Darby's Rangers) is destroyed behind enemy lines in a heavily outnumbered encounter at Battle of Cisterna, Italy.

0 notes

Text

The Battle of Marathon

The year is 490 BC and we find ourselves on the plains of Marathon, just a few miles from the city of Athens.

The Persian army, led by King Darius I, landed on the shores of Greece with the intent to conquer the land. The Athenians, under the leadership of their general Miltiades, mobilized their army and marched to meet the Persians on the battlefield.

As we stand on the plain, we can see the two armies facing each other. The Persians, with their vast numbers, appear overwhelming, but the Athenians stand resolute, determined to defend their homeland.

The day of the battle dawns, and both armies prepare for the fight. The Athenians form their phalanx, a wall of shields and spears, and wait for the Persian charge.

The Persians, seeing the Athenian formation, begin to run toward them. The Athenians, staying in formation, absorb the charge and counterattack with their spears. The Persians are surprised by the Athenian tactic and begin to falter.

Miltiades orders his troops to break the formation and attack the Persian flanks. The Athenians, with their superior tactics and training, are able to break through the Persian lines and rout the enemy army.

We watch in amazement as the Persians flee back to their ships, pursued by the victorious Athenians. The Battle of Marathon is over, and the Athenians have won a decisive victory against their much larger foe.

As we walk across the battlefield, we see the fallen soldiers of both armies lying on the ground. We realize the true cost of war and the bravery and sacrifice of those who fought for their beliefs and their homeland.

In conclusion, experiencing The Battle of Marathon firsthand has been a truly incredible and humbling experience. We have witnessed the bravery and skill of the Athenian army, and the cost of war on all sides. It is a reminder of the importance of defending one's homeland and the sacrifices required to do so.

More Information:

The Battle of Marathon was fought between the Athenians and the Persians. The Persian army, led by Datis and Artaphernes, landed on the plain of Marathon, about 26 miles northeast of Athens. The Athenians, led by general Miltiades, marched to confront them. Despite being vastly outnumbered, the Athenians managed to defeat the Persians thanks to their superior tactics and discipline. They formed a phalanx, a tight formation of heavily armed infantry, and charged at the Persian lines. The Persians, caught off guard by the ferocity of the Athenian attack, were forced to retreat to their ships. The Athenians pursued them and managed to capture seven Persian ships. The Persians, realizing they had lost the battle, sailed south to attack Athens from the sea. However, the Athenians had anticipated this move and had left a small force to defend the city. The Persians were unable to breach the city walls and were forced to withdraw. The Battle of Marathon was a decisive victory for the Greeks and prevented the Persians from conquering Athens. It also boosted the morale of the Greeks and inspired them to continue resisting Persian aggression. The battle became legendary in Greek history, and the word "marathon" became synonymous with a long-distance race, in honor of the messenger who ran from Marathon to Athens to announce the victory.

0 notes

Text

Ah, it's so difficult to draw expressions on bearded men!

A little sketch of Miltiades, Athenian general at the Battle of Marathon. To be honest, I'm more confident doing traditional art, but I really wanted to experiment with Miltos' hair. I read somewhere that the name "Miltiades" was given to red-haired babies and I wanted to give him red hair.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Travel Log

Introduction: The ancient Greek hoplites were heavily armed infantry soldiers, known for wearing extensive armor, carrying a large rounded shield, spears, and a sword.

-------------------------------------------------------------

You can call me Linus Andino. After seeing the attack on Athens, my city, I decided to join the strong Greek army in the hope of receiving honor and victory.

Battle of Marathon 490 BC:

I am now in northern Attica. The Persians have started their invasion. It's both depressing and enticing to smell iron and blood together. The scene is hectic and confusing. There is an extremely large invading force, much larger than our own. The Persian cavalry has an edge due to the flat battlefield that is bordered by hills and sea. The generals are hesitant before making any decisions as we have to consider the advantage that the Persians have due to the geography and the magnitude of their troops. The views of the generals seem to differ. Some advise against taking a chance in a battle because they believe we are too little to compete with the Persians' army. Miltiades is passionate about a plan of attack. He says that us hoplites should form a line equal in length to that of the Persians. He is ordering us to charge headlong into the enemy line. Although the outcome doesn't seem hopeful, I still trust commander Miltiades.

The Athenian army’s formation was as follows:

a. The right flank was 500 meters wide. There, Miltiades’ unit had a depth of eight ranks, resulting in a total of 4.000 soldiers.

b. The center was also 500 meters wide, manned by 2.000 soldiers with a depth of four ranks.

c. The left flank was 625 meters wide, where 5.000 soldiers were placed in ranks of eight.

5:30 A.M. Phase 1: At this point in the battle, we had come within 200 meters of the Persian formation when we began to charge towards the enemy lines in an effort to avoid suffering heavy losses from the Persian arrows. There were no recorded injuries or fatalities during this period, therefore it appears that the strategy was successful.

Phase 2: After destroying two Persian flanks, we assembled a phalanx of 9,000 soldiers and struck the enemy center from behind. We surrounded the Persians from two sides, causing chaos and confusion as they fled in fear. Several men drowned or were killed by us as they fell into the numerous swamps on the battlefield while trying to flee.

Phase 3: We started following the Persians as they fled to their ships. Of the roughly 600 Persian ships, we could only capture six. At around 8:30, the Battle of Marathon came to a close after three hours of fighting. Only 192 of our soldiers died while the Persians lost 6,400.

The Persians were defeated by Miltiades' strategy, and the triumph of "the Marathon men" caught the attention of the Greek people as a whole. The modern marathon was developed as a result of the story of the messenger Pheidippides, who ran 25 miles to Athens to give the news of the Persian defeat.

-------------------------------------------

Lysistrata, The Play:

Greek theater, one of the first manifestations of western civilization, drew large crowds to exquisitely designed outdoor venues and offered deeply moving entertainment that was immensely popular at the time and continues to be so with many more succeeding generations throughout history. The city-state of Athens served as the art form's cultural epicenter, where theater was institutionalized as a component of the Dionysia festival, which honored the deity Dionysus, whose rights were linked to the theater.

Today I will be seeing Lysistrata. This Peloponnesian War-era play features Lysistrata, a lady who is sick of the never-ending, apparently pointless battle. She persuades the women from every Greek city-state to assist her in her attempt to put a stop to the males' endless conflicts after choosing to take matters into her own hands. Naturally, she must also make use of one of the few abilities available to women at the time—the ability to forbid them from having sex with their husbands until the war is ended. Naturally, all the women swear a very specific oath that spells out precisely what they can and cannot do as part of the agreement and cheerfully agree to avoid any contact with their husbands and sexual activity. To show the males they mean business, the ladies then swarm the Acropolis, where the city's treasury was situated. The ladies put a stop to the war machine by gaining control of their treasury because the conflicts cannot be financed without these funds. When Lysistrata meets with the magistrate in charge, she explains that women in Greece have long been angry about the way males behave foolishly when at war and harm everyone around them. The husbands soon start to feel the effects of not enjoying their wives' company. The ladies are also desolate and long for their husbands, but Lysistrata encourages them to stick with the cause by telling them that they must be firm even in the face of genuine begging from their spouses. Ancient Greek men and women finally come to an understanding to start negotiations for peace. The men, however, just cannot put fighting and bickering behind them and begin to criticize several of the terms of the agreement. Then Lysistrata has the brilliant idea to parade a stunning lady before them, driving them to such desperation that they would sign anything. Of course Lysistrata wins in that bet.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Theater of Dionysus:

The Theater of Dionysus in Athens will be my next stop. It is built into a natural hollow at the southern slopes of the Acropolis and it is the first theater in the world.

The theater gets its name from Dionysus who is the god of wine and fertility. He was regarded as the patron of the arts. He developed wine and popularized viticulture. He possessed a dual character, mirroring the dual nature of wine, bringing joy and divine rapture on the one hand, or bringing harsh and blinding anger on the other. Several yearly festivities in ancient Greece honored him. The City Dionysia, which included drama for five days, was the most significant.

The open-air theater is insanely large. The most important individuals sit in the front row, which is made of marble. The priests of Dionysus and the chief magistrates of Athens reserved these rows. Priests claimed 50 of the 67 front row seats, then came the officials, the guests of honor, then finally the ordinary citizens of Athens. The orchestra, a circular area beyond the front row where the Chorus would perform songs and dances, included the altar of Dionysus in its middle. The orchestra level was around 3 meters higher than the shrine. The stage, a large rectangular foundation on which the performers would perform their sections of the play, was located behind the orchestra. When they were no longer required on stage, the performers would retire here, or they would leave when it was time to change costumes.

The surrounding woodlands could be seen in the distance, along with the olive-colored hills and the deep blue sky above and the Acropolis behind it. The plays of the most significant ancient Greek playwrights, Aeschylus, Aristophanes, Euripides, and Sophocles, had their world premieres in this theater.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The Battle of Salamis:

Background: Following the Battle of Thermopylae in August, 480 BC, the Athenians had fled to Salamis as the Persians seized and burnt their city. After the draw at the Battle of Artemisium, the Greek fleet joined them there in August. Themistocles, the commander of the Athenians, persuaded the Spartans to stay at Salamis by arguing that a wall across the Isthmus was useless as long as the Persian army could be transported and supplied by the Persian navy. The Spartans wanted to return to the Peloponnese and build a wall to close off the Isthmus of Corinth and prevent the Persians from defeating them on land. His claim relied on a special interpretation of the Delphic oracle, which, in typically ambiguous Delphic fashion, foretold that Salamis would "bring death to women's sons'' but also that the Greeks would be protected by a "wooden wall." Themistocles said that Salamis would bring death to the Persians, not the Greeks, by interpreting the wooden wall to represent the fleet of ships. In addition, some Athenians who remained in Athens took the prophecy literally, erected a wooden wall to block access to the Acropolis, and walled themselves in. They were all slaughtered, the wooden wall was overcome, and the Persians set fire to the Acropolis.

The Persian King Xerxes has been anticipating this. Athens is being reduced to a pile of blazing ruins by his army, and his ships have just trapped the little Greek navy at Salamis at the mouth of the Bay of Eleusis. Finishing them off was the only thing left to do. Xerxes had his throne put up on the cliff overlooking the two ships so he could watch what he imagined would be a triumphant sight. He was eager to obtain a grandstand view of the event. Suddenly, in a cacophony of noise, sailors and hoplites on the top deck rallied to their stations, trierarchs and boatswains barked their orders, and the rowers of the combined Greek fleet braced for action….

In order to increase safety, we have already transferred women and children to Aegina. We are now boarding the ships in order to be ready to fight the Persians. The Greek war council is currently in session. It is severely storming. With the primary justification that, in the event of failure, they might seek safety within the Peloponnese and carry on the struggle from there, the Spartan Eurybiades proposed that the naval battle be conducted at the Isthmus of Corinth. The Corinthians were on his side. Themistocles urged that the naval combat take place on Salamis, and the Megarians and Aeginians joined him in this demand. He felt that the little Greek forces had no chance of winning if they engaged the vast Persian navy in battle on the wide seas. On the contrary, the Strait of Salamis was the perfect location for a naval fight since it prevented the numerous Persian ships from growing in number.

Themistocles is a genius. He pulled out the following ruse to hasten the naval battle: He stealthily sent Sikinos' instructor to the Persians, telling them that the Greeks were reportedly about to depart Salamis, and that if they wanted to beat them, they would have to rush to catch them. Xerxes fell for the ruse and gave the order to surround the Greek fleet and prevent its withdrawal to the Isthmus of Corinth.

The two fleets began facing off at first light on September 28 or 29 in 480 BC, prepared for a naval conflict. The first to rush was us. We were moving closer to triumph thanks to our battle songs, trumpets, cries, smoke, and most importantly, the strength. The fight raged all day, and now that dusk has fallen, I can only make out shattered pieces of wood and the lifeless remains of Persian soldiers floating around in the water.

We have defeated the Persians. Themistocles' plan and our superior skills were a big part of this spectacular triumph.

---------------------------------------------------------------

The Persians:

Today I will be seeing “The Persians”. The Persians is an ancient Greek tragedy written by the Greek tragedian Aeschylus during the Classical period of ancient Greece.

Greek tragedy was a well-known and important genre of ancient Greek theater that dates back to the late 6th century BCE. The most well-known authors in this genre were Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Greek tragedy gave way to Greek comedy, and these two genres combined established the framework for all contemporary theater. Persians stands out among the extant ancient Greek tragedies in that it dramatizes current happenings as opposed to things that took place in the past during the time of mythical heroes. In particular, their defeat at the Battle of Salamis, the final Persian retreat from Greece in 480, is the subject of the drama. Aeschylus universalizes the tragedies and lessons of one particular war while simultaneously glorifying the winners. The mythical play Persians was originally performed alongside three other plays, each of which could stand alone or be thematically related to a military threat. The playwright from Athens likely participated in the battles of Salamis and Marathon against the Persians led by Darius. As a soldier and combat veteran of battles with Persia, Aeschylus was biased in favor of the Athenians and purposefully painted the enemy as haughty, opulent, and overly sentimental. He also enables us to feel compassion for Xerxes's household and the royal court.

The tragedy at Salamis is announced to the Persian queen by a messenger in the Persian city, where the story is situated. The drama concludes with the return of the shattered and degraded Persian monarch, Xerxes, and credits Persia's defeat to Greek independence and valor as well as the gods' retribution of Persian stupidity for venturing past the boundaries of Asia.

Aeschylus's Persians, a lavish play presented through the voices of Persian courtiers, mixes visual splendor with potent, lyrical storytelling.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Today in History - Battle of Marathon (September 12, 490 BCE)

* Traditional date of the battle

* Helmet of Miltiades the Younger , archaeological museum of Olympia. Miltiades was an Athenian general who insisted that Greeks should attack invading Persian forces at Marathon instead of retreating towards Athens.

Source: Oren Rozen [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

The actual helmet worn by the Athenian General Miltiades at his victory over the Persians at Marathon. He dedicated it to the god Zeus.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

A Greek scholar reviews “The Idea of Marathon” of Sonya Nevin

“The idea of Marathon: battle and culture

Sonya Nevin, The idea of Marathon: battle and culture. London; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022. Pp. 256. ISBN 9781788314206

Review by

Manolis Petrakis, Directorate of the National Archive of Monuments, National Archaeological Museum of Athens. [email protected]

Preview

This reader-friendly book provides more than it claims. It offers a handy overview of (Athenocentric) ancient Greek history and historiography from the 6th century BCE to its ancient and modern reception, focusing on the Battle of Marathon. The twelve chapters are preceded by a brief Introduction, where the author sets the stage at the twilight of the Persian Wars, elaborates on the influence of the name “Marathon”, and sets the book’s goals, namely, to explore the circumstances that led to the battle, the battle itself, and its cultural influence. Next, Nevin briefly introduces Greek historiography, (not surprisingly) highlighting Herodotus as the primary source of evidence—for herself as well as others—along with other literary texts, archaeological finds, and inscriptions.

The first five chapters are devoted to the events that led to the battle and to introductory information on Greece and Persia before the war. Chapter 1, “Athenians at a Turning Point”, offers an overview of Athens before the Persian Wars. First, the author emphasizes the changes of regime from oligarchy to tyranny to the shaping of democracy. She then draws attention to the elite families of the city and their role in politics. Finally, the chapter closes with general information on the Greek military, especially the hoplites.

Chapter 2, “The Greek World”, moves swiftly from Athens to Sparta, Boeotia, and Asia Minor. Nevin provides an excellent overview of Greek identity’s shared attributes during the Archaic Period, namely origin, language, customs, and religion. The interaction of the other Greek cities and areas with Athens is thoroughly explored. Especially in the case of Ionia, relations between Greeks and non-Greeks are discussed. The chapter ends with the Persians in Ionia, an ideal way to smoothly transition to the third chapter.

Chapter 3, “Persia”, discusses the Persian Empire, providing the historical context of its creation and expansion. It deals with various subjects, such as Persian identity, cultural characteristics, and economy. In addition to the historical overview and the presentation of crucial personalities, Nevin analyses Persian weaponry, drawing comparisons between the Greek and Persian militaries. The author handles her source material with care, also drawing from Persian evidence, which is important given that “we are disproportionately dependent on Greek sources” (p. 33), as she rightly points out.

Chapter 4, “Revolt in Ionia”, explores the events and the cause of the Greek-Persian Wars, stressing the importance of the Ionian Revolution. Nevin takes a fresh look at how Darius’ shifting from his predecessors’ manner of governing triggered the Revolt. She demonstrates how Aristagoras’ unfortunate attempt to take over Naxos in favor of Persia resulted in Miletus’ revolt against Persian authority. She then provides an overview of the formation of the Ionian League and the Ionian Revolt itself. Nevin uses some archaeological finds, in addition to the historical sources, “as evidence of siege [that] can be seen in the archaeology of Paphos” (p. 57), referring to a Persian siege of Cyprus, but unfortunately does not cite her archaeological sources, a practice which is not helpful for convincing the reader. This is a problem throughout the book.

Chapter 5, “The Plain of Marathon”, primarily deals with Hippias, Datis, Artaphernes, and Miltiades, while only two pages discuss the plain (p. 69–70). Some basic information on the topography of the Marathon plateau is given. Note 14 cites some of the main publications on the subject, but the omission of Dionysopoulos’ monograph is a serious one,[1] as many topographical issues have been reconsidered since the most recent publication mentioned, that of van der Veer in 1982.[2]

The following two chapters pursue the battle and the events immediately after it. In Chapter 6, “The Fight”, after briefly discussing the mythical stories of gods and heroes who contributed to the fight, Nevin presents the various theories and interpretations of the battle formations and the role of the Persian cavalry. The narrative continues to follow Herodotus, as does the whole book, but especially here more space given to modern scholarship. This chapter is a good sample of the author’s excellent knowledge of the subject and her critical approach to literary texts, as she challenges the sources, e.g., on the numbers of combatants, and she also notes possible anachronisms.

Chapter 7, “Surviving Marathon” continues this inquiry, examining the events immediately after the battle. Nevin convincingly characterizes as symbolic the Athenian army’s two visits to sanctuaries of Heracles on its way home. She investigates the original Marathon road, concluding that we must not rely on the details that could be fictional. The author continues with the treatment of the wounded and a brief note on the spoils, which either benefited the Athenian treasury or became offerings to the gods. Alongside Miltiades’s helmet, a reference to a second helmet dedication, taken as booty, is omitted.[3] The chapter concludes with the treatment of the dead. In respect to the tumulus, we shall note that Antonaccio first stated the idea that it was adapted from an earlier tomb.[4] Also, a mention of the cenotaph at Kerameikos would have been welcome.[5]

In the remaining five chapters, Nevin investigates the battle’s impact from antiquity to modern times. Chapter 8, “Events after Marathon”, touches on numerous topics in a few pages. First, the author explores the effects of this battle on the Persian Empire, concluding that they were insignificant. Then she proceeds with the significance of Marathon in shaping Athenian identity, concluding that this battle eventually became its cornerstone. Next, the author presents an overview of the commemorative monuments and of festivals established in honour of the event. She continues with Miltiades’ decline and death to the formation of the Delian League. Finally, the chapter closes with Aeschylus’ Persians; Nevin shows that this tragedy signifies the beginning of the process of shaping Greek (Athenian) identity through reference to the Persian Wars.

In the first part of Chapter 9, “Memories of Marathon in Fifth-Century Art and Literature”, she stresses the importance of the Athenian Treasury and other Cimonian monuments at Delphi. Again, only Pausanias is mentioned, although the monuments themselves have been excavated and published.[6] She proceeds with more discussion of material culture, the Stoa Poikile, pottery, and the Temple of Nemesis. The chapter closes with an examination of historiography and theatrical plays.

Chapter 10, “Marathon beyond the Fifth Century”, surveys the presence of the battle in the oratorical speeches, philosophy, and historiography from the 4th to the 2nd centuries BCE. The author shows how Athenian rhetoric and propaganda kept using the battle in various circumstances. Conversely, she demonstrates how and why Alexander did not use Marathon in his symbolic anti-Persian gestures. This chapter offers a summarized overview of Greek history; it deals more with the Greek-Persian Wars’ impact in general rather than Marathon in particular.

Chapter 11, “Marathon under Rome”, proceeds from the Hellenistic to the Roman Imperial Period. After discussing relevant passages from Pausanias, Lucian, and especially Plutarch, Nevin convincingly concludes that these authors did not emphasize who fought (as was the case in Classical/Hellenistic Athens) but rather the virtues connected with the battle.

Chapter 12, “Marathon after Antiquity”, brings together much interesting material. It opens with an 11th century CE Persian epic, Wamiq u ‘Adrha, which follows Miltiades’ son, Mentiochus. Then it outlines Marathon’s survey and excavation history, from the original antiquarian projects (Chandler, Fauvel, Leake) to the formal excavations (Schliemann, Philios, Stais). Probably Fink’s monograph deserved to be consulted here.[7] Finally, Nevin’s narrative reaches the modern era, with the development of the Soros into an archaeological site. More elaboration or a reference was needed on the long debate concerning the Soros’ identification as the Athenian Tumulus.[8] Next, the author notes the erection of the Marathon Archaeological Museum, for which a citation is also needed.[9] Nevin mentions the copy of the Aristion monument next to the Soros, but she fails to mention the marble replica of the Trophy set near its original site after Korres’ comprehensive study.[10] Finally, a book dealing with the reception of the Battle of Marathon would greatly benefit from a reference to the 1929 copy of the Athenian Treasury of Delphi, constructed by Ulen next to the Marathon Lake’s dam, and ideally a discussion of its symbolism.[11] Next, Nevin deals with Byron’s poetry and its resonance. A sub-chapter follows on 19th-century European youth’s classical education and an excellent overview of the modern Marathon run, demonstrating the influence that Browning’s poem may have had on its shaping. Again, a reference to the Marathon Run Museum is missed.[12] Then the author jumps to the use of Marathon in the propaganda of the military dictatorship in Greece and sketches the situation in 1930s Persia-Iran. The chapter ends by focusing on 21st-century novels on Marathon.

A short afterword sums ups the book conveniently, highlighting that “Marathon is also a story of how events are remembered” (p. 191). A concluding index, as well as opening lists of Illustrations and Abbreviations are provided.

Throughout the book, Nevin provides a helpful overview of Greek history, to which she incorporates the presence and the use of the Battle of Marathon. The structure is clear and easy to follow. Some translated ancient texts, mainly Herodotus, contained in the text are useful to the reader, and translations are generally accurate. The book is also commendably readable and virtually without misprints (exceptions: p. 19 Aeolians from Aeolus, not Aeolis, p. 131 Acharnians, not Acharnanians) or inconsistencies (the three citations to Inscriptiones Graecae are inconsistent p. 205 note 13: IG I31472; on the same page note 28: IG ii 1.47I and on page 209 note 46: IG I3 435). In contrast, the publisher did not pay attention to the quality of the few illustrations (11): the line drawings are faint, the legends on the maps are barely readable, and the only vase photograph (fig. 11) does not meet publication standards.

My main criticism of this volume would be its limited bibliography and the scarcity of references or citations within the body of the text, as has already been noted above. Be this as it may, Nevin offers readers many interesting observations that provide much food for thought. There are a few inaccuracies/overgeneralizations, e.g. (p. 6) the Panathenaea (from the context we get the Great Panathenaea) are mentioned as an annual festival, while they were in fact celebrated every four years (as opposed to the Lesser Panathenaea, which were annual) or (p. 65) the modern Marathon Run is not from east to west Attica, but central, still closer to the east.

The writing style is by no means academic, yet it is graceful. Accumulations of excessively short sentences (e.g., p. 86: “Narrow paths. Soft soil. Water. Plants. Panicked men.”) and informal vocabulary (e.g., p. 6 “‘Tyrant’ was not a dirty word”, [on Corinthian helmets] “they looked fantastic”, [on Spartans] “They were not super-soldiers”, “smaller players Plataea, Thespiae and Tanagra”, “Mission on”, “Fantastic sass”, etc.) show that the book targets a larger audience than just fellow classicists. That probably explains the scarcity of secondary sources. Given the intended readership, most of the issues mentioned above are also irrelevant; Nevin’s writing could be nothing but successful in attracting non-specialists. The book is straightforward to read and offers a short, concise, and informative overview of the Greek-Persian Wars and their reception. It therefore represents a welcome addition to the vast bibliography on Marathon and ancient history in general. Newcomers to the study of classics, undergraduates, or interested members of the public looking for an overview of the Battle of Marathon will find this volume very useful.

Bibliography

Antonaccio, C.A. 1995. An Achaeology of Ancestors. Tomb Cult and Hero Cult in Early Greece. Lanham.

Dionysopoulos, Ch.D. 2015. The Battle of Marathon. A Historical and Topographical Approach. Athens.

Fink, D.L. 2014. The Battle of Marathon in Scholarship. Research, Theories and Controversies since 1850. Jefferson, North Carolina.

Korres, M. 2017. “Το Τρόπαιον Του Μαραθώνος. Αρχιτεκτονική Τεκμηρίωση.” In Giornata Di Studi in Ricordo Di Luigi Beschi / Ημερίδα Εις Μνήμην Του Luigi Beschi: Italiano, Filelleno, Studioso Internazionale. Atti Della Giornata Di Studi, Atene 28 Novembre 2015, edited by E. Greco, 149–202. Tripodes 17. Atene.

Petrakos, V. 1996. Marathon. Athens.

Raubitschek, A.E. 1940. “Two Monuments Erected after the Victory of Marathon.” American Journal of Archaeology 44 (1):53–9. doi:10.2307/499590.

Robinson, B.A. 2013. “Hydraulic Euergetism. American Archaeology and Waterworks in Early-20th-Century Greece.” Hesperia 82 (1):101–30. doi:10.2972/hesperia.82.1.0101.

Scott, M. 2010. Delphi and Olympia. The Spatial Politics of Panhellenism in the Archaic and Classical Periods. Cambridge; New York.

Steinhauer, G. 2009. Marathon and the Archaeological Museum. Athens.

Valavanis, P. 2010. “Σκέψεις Ως Προς Τις Ταφικές Πρακτικές Για Τους Νεκρούς Της Μάχης Του Μαραθώνος.” In Marathon. The Battle and the Ancient Deme, edited by K. Bouraselis and K. Meidani, 73–98. Athens.

———. 2019. “What Stood on Top of the Marathon Trophy.” In From Hippias to Kallias. Greek Art in Athens and Beyond. 527-449 B.C., edited by O. Palagia and E. Sioumpara, 145–56. Athens.

van der Veer, J.A.G. 1982. “The Battle of Marathon: A Topographical Survey.” Mnemosyne 35 (3):290–321.

Notes

[1] Dionysopoulos 2015.

[2] van der Veer 1982.

[3] Museum of Olympia no. B 5100.

[4] Antonaccio 1995, 118–9.

[5] Raubitschek 1940.

[6] See Scott 2010, 77–81 with previous bibliography.

[7] Fink 2014.

[8] For the debate see Valavanis 2010, 73–98.

[9] Petrakos 1996; Steinhauer 2009.

[10] Korres 2017; Valavanis 2019 with previous bibliography.

[11] Robinson 2013.

[12] https://marathonrunmuseum.com/en/.”

Source: https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2023/2023.01.09/

Manolis Petrakis

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The helmet of Miltiades.

Miltiades (c. 550 – 489 BC) was an Athenian Greek general, known for his strategies that led to victory against a much larger number of Persians in the Battle of Marathon (490BC), one of the most famous battles in world history.

After the victory, Militiades gave his helmet as an offering to the Temple of Zeus in Olympia as it is evident from the script carved on it (ΜΙΛΤΙΑΔΕΣ ΑΝΕ[Θ]ΕΚΕΝ [Τ]ΟΙ ΔΙ = Miltiades dedicated (this) to Zeus). The helmet can be seen nowadays in the Archaeological Museum of Olympia.

#greece#europe#history#ancient greece#persian wars#battle of marathon#miltiades#greek history#olympia#elis#peloponnese#archaeological museum of olympia#peloponnisos#ilia#mainland

274 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Name: Miltiades

Pride: Crushing Rock Pride

Mother: Bhumi

Father: Unnamed Lion

Siblings: Kun, Avani (Littermate), Ila

Partner(s):

Children:

Generation: 2

Backstory: TBD

0 notes