#gerda stevenson

Text

Play for Today: Clay, Smeddum and Greenden (BBC, 1976)

"What ails you?"

"Ails her? You would greet yourself if you saw your life ruined."

"Well, I'm right sorry you're taking it like that. But, losh, it's a small thing to greet over."

#play for today#clay smeddum and greenden#single play#classic tv#bbc#1976#lewis grassic gibbon#bill craig#moira armstrong#victor carin#anne kristen#gerda stevenson#fulton mackay#bill fraser#joan fitzpatrick#eileen mccallum#maev alexander#fiona knowles#brian cox#claire nielson#isobel gardner#a trilogy of connected plays based on the short stories of celebrated Scots writer Gibbon; this got a repeat on bbc4 a few months back and#im using a brief visit home to catch up on stuff I'd recorded off the tv. i think this is on iplayer for the rest of the year and it's well#worth looking out (tho I'd recommend subtitles; the heavy accents and scots dialogue can be difficult to parse). an atypical example of a#PfT‚ but an excellent example of the series' occasional forays into more regional work. Clay‚ the first (and perhaps best) of the three#short plays concerns a man's obsession with the land he works‚ to the detriment of his family and his health. shot with an almost folk#horror sensibility‚ it's a subtle beast; quite unlike the second‚ a broad comic piece about a tough matriarch and her various children. the#third has a more overt sense of the supernatural again‚ or at least a kind of psychological horror (very much subtextual) in its study of a#sensitive urban woman driven slowly out of her wits by dual isolations of a new home in the country and a cruelly distant husband#all three plays benefit from centering strong female characters‚ all three rewarded by excellent casting. as i said‚ watch if you can

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Head of a Young Woman

Gerda Stevenson

I press my brow to cold glass –

two women, head to head:

your face tilts like a ship’s prow

challenging the wind,

morning sky over the North Sea

in your salt-washed cheeks

and eager, blue-green eyes.

Your hair falls like mine

from a centre parting, though holds

no trace of grey in its peat brown sweep.

Five thousand years between us, and yet

not a moment, it seems – recognition

like that spark you’d know how to strike

from stone. Thought tugs at your mouth’s harbour,

a half-smile about to slip its mooring into laughter.

Your skull lies beside you, mute echo,

shell-white in spotlit stillness – every curve

and crevice mapped by expert minds:

your mask their exquisite calculation,

more real to me than any excavated bone.

Did you sleep, wake, love and weep

in the dark air of honeycomb chambers

built by shores I’ve only glimpsed

from plane and car – my stay too short

and anyway, my timing out of season?

I want to know you, unknown woman,

walk with you the cliffs at Silwick,

tread the paths of Scalloway, hear

your language beat the air again

with skua, scart and arctic tern,

learn your life, those days that stretched

behind your step, and (though you couldn’t guess

their end would come too soon) gave you

such a fearless gaze of hope.

#poetry#life#archaeology#place#shetland#encounter#gaze#imagination#gerda stevenson#woman#power#agency

0 notes

Text

Gerda Stevenson - Aye The Gean (Scots)

#soft celtic-inspired folk#gerda stevenson#aye the gean#scots#sco#germanic#indoeuropean#europe#scotland#2014#2010s#folk#Bandcamp

0 notes

Text

Quines: Poems in tribute to women of Scotland

I love a book that discusses its sequencing. Almost as much as I love the acknowledgement that English, Scots and Gàidhlig are the languages of Scotland. That said, the introduction can be a bit scattershot at times. Very Oh, we’re done? in places. I did like that some poems were written from the perspective of family or objects related to the person but I felt it could have been used better…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Giardinaggio con Galina di Gerda Stevenson

Giardinaggio con Galina di Gerda Stevenson

Gerda Stevenson, attrice, regista e scrittrice scozzese (1956)

Ogni parola che, io e te,abbiamo piantato è cresciutacon così grande lentezza:ciascuna un seme riposto profondo,nel terriccio della tua mente.In silenzio, abbiamo atteso,nel susseguirsi delle stagioni, e nel frattempoappreso che le mani sanno parlare;finché, alla fine,germogli di suoni acerbi s’estendonodalle radici fino all’ancia…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Blue Black Permanent (Margaret Tait, 1992)

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Blue Black Permanent | Margaret Tait | 1992

Gerda Stevenson

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Blue Black Permanent

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Abdication of Mary Queen of Scots

Tak ma croon, an dinna fash -

aa yon wis ower fur me lang syne.

Ye needna glaum at ma silk goon

wi yer coorse nieve - I'm nae threit;

I'll sign yer muckle scroll, dae whit I maun,

past carin noo; thae last three days ma flesh

an saul hae wandert shores o hell-fire, dule an daith:

twa bairns I cradled in ma wame aa through the months,

sae douce, o Spring an Simmer; slippit cauld an stieve

intae the dowie air o Leven's grey stane waas,

claucht frae ma jizzen, an burriet ootby, wi nae prayer,

fur aa I ken, an nae sang, twa scraps o heiven,

aa ma howp in their twin licht smoorit noo,

tho milk's aye buckin frae ma breists unner ma lace an steys;

an I couldnae gie a fig fur yer fouterin laws,

sat there, scrieven yer Latin clatters o queens an kings -

O, I could run rings roon ilka yin o ye in Greek an aa,

as weel's ma bonnie French, but yer naethin, naethin noo,

jist ghaists; an, och, Mary, Mary Seton, last

o ma fower leal ladies, dinna waste yer tears

oan gien up a bittie gowd an glister; haud ma airm

if it helps, but dinna, dinna greet fur this.

Gerda Stevenson

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Braveheart: Limited Edition Gift Box Set Includes Exclusive Art Cards + Script + 20th Anniversary Commemorative Coin in Leather Pouch (2-Disc Limited Edition) (Region Free + Fully Packaged Import)

Braveheart: Limited Edition Gift Box Set Includes Exclusive Art Cards + Script + 20th Anniversary Commemorative Coin in Leather Pouch (2-Disc Limited Edition) (Region Free + Fully Packaged Import)

Price: (as of – Details)

Already Listed Is Discontinued By Manufacturer : No Language : English Package Dimensions : 28 x 18 x 5.8 cm; 300 Grams Item part number : 890807008-MIG Run time : 2 hours and 50 minutes Actors : Mel Gibson, James Robinson, Sean Lawlor, James Cosmo, Gerda Stevenson Subtitles: : English Studio : 20th Century Fox | Excel Home Videos ASIN :…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

Celebrating the winter solstice with poems for the year's turning point; Traces by Gerda Stevenson, Harriet Walter reads Piano by D. H. Lawrence, Noma Dumezweni reads Edna St Vincent Millay's What My Lips Have Kissed and Simon Russell Beale reads Thom Gunn's My Sad Captains.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

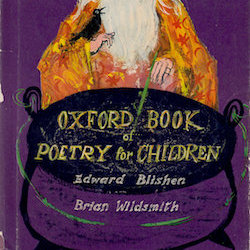

some anecdotes, an odd poem, and incidental history

(1) some anecdotes

The other day, I was trying to find the text of an old childhood favorite poem of mine, and google just wasn’t turning it up.

This happens to me pretty regularly. My early poetry was almost entirely from the Oxford Book of Poetry for Children, which is fantastic and gorgeously illustrated and full of the most eclectic selection of poems imaginable.

It’s got all sorts of nursery classics, of course, from Carroll (“...If seven maids with seven mops/Swept it for half a year...”) to Silverstein (“Nobody loves me/Nobody cares/Nobody picks me peaches and pears...”).

Then there’s the classics that maybe aren’t so obviously for children, like Dickinson (”I’m Nobody! Who are you? Are you -- Nobody -- Too?”) and Yeats (“The silver apples of the moon,/The golden apples of the sun”). Those seem reasonable enough once you put them with the others; “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” goes opposite Shel Silverstein’s “Nobody loves me,” with a cute silhouette of a little boy, and it seems as natural as anything to cut your teeth on Dickinson.

And then there’s the weird ones. These leave you wondering, as an adult, why someone put them into a book of poetry for children -- but as a child you don’t see anything strange about it, of course. And I tend to think it’s one of the great strengths of this book that it does include these; children have weird dark things going on inside their heads, and giving them words for those isn’t a bad thing. Still -- I wrote weird stuff, as a kid (like I don’t now, but), and it’s not hard to have some guesses why, once I look back on excerpts of what I was reading:

‘I wish the wind would blow through you,’

said Meet-on-the-Road.

‘Oh, what a wish! Oh, what a wish!’

said Child-as-it-Stood.

‘Pray, what are those bells ringing for?’

said Meet-on-the-Road.

‘To ring bad spirits home again,’

said Child-as-it-Stood.

‘Oh, then I must be going, child!’

said Meet-on-the-Road.

‘So fare you well, so fare you well,’

said Child-as-it-Stood.

‘The years passed like shooting stars,

They melted and were gone,

But the path itself seemed endless,

It twisted and went on.

‘I followed it and thought aloud,

“I’ll be found, wait and see.”

Yet in my heart I knew by then

The world had forgotten me.’

Frightened I turned homeward,

But stopped and had to stare.

I too saw that signpost with no name,

And the path that led nowhere.

Yeah -- weird childhood. But fantastic -- both the childhood, and the poems. The latter really stuck with me. It didn’t hurt that they are all of genuinely excellent quality, though different kinds; obviously you can’t exactly compare Robert Louis Stevenson against Blake against “Solomon Grundy/Born on Monday...” head-to-head-to-head, but none of them are anything like bad at the thing they’re being.

Plus, it’s just really quotable poetry. Especially if your whole family’s grown up on it, so that everyone speaks the same language. I’m not sure a month of my life has gone by where I didn’t recite at someone --

Don’t Care didn’t care,

Don’t Care was wild:

Don’t Care stole plum and pear

Like any beggar’s child.

Don’t Care was made to care,

Don’t Care was hung:

Don’t Care was put in a pot

And boiled till he was done.

(What can I say; nothing takes the wind out of a teenager’s sails like reciting that to them when they’re in the middle of a fit of pique.)

Or someone will get started off on nagging someone else with “A man of words and not of deeds/Is like a garden full of weeds/And when the weeds begin to grow/It’s like a garden full of snow,” and by the end the entire family will be reciting together for “And when your back begins to smart,/It’s like a penknife in your heart;/And when your heart begins to bleed,/O then you’re dead, and dead indeed.”

(I did mention it was weird poetry.)

There’s always late risers to be teased with “A potato clock, a potato clock/Has anybody got a potato clock?” Anyone tagging along at someone else’s heels can expect to hear “I have a little shadow that goes in and out with me/And what can be the use of him is more than I can see.” Breakfast is accompanied by the eggs poem, with quips for every way you can have them done (scrambled: “I eat as well as I am able,/But some falls underneath the table.”) Sleepy small children get “the Sugar-Plum Tree/In the garden of Shut-Eye Town” recited in full, if they’re lucky. And of course adorably bossy tiny people get tolerant recitations of “James James/Morrison Morrison/Weatherby George Dupree/Took great/Care of his Mother,/Though he was only three.”

All that to say, then: growing up in my house, this particular poetry gets under your skin. You find yourself thinking in it, at odd moments. You have quotes on the tip of your tongue and you’re not quite sure where they’re from.

So you go look them up, because it turns out that not everyone in the world knows what you’re on about when you start in on “The King asked/The Queen, and/The Queen asked/The Dairymaid...” And that one, it turns out, is Milne, and really everyone should know it; and later you discover that other poems are Blake or Lear or Yeats or Farjeon (and go “oh, that’s why I liked that one so much, no wonder”); and it’s weird and delightful to find out that these childhood poems of yours are actually the great classics of English literature.

So, yeah, half the time when you go look a poem up, yeah, it’s Auden or Wordsworth or someone, that would explain why it’s so good. (And, yeah, maybe this is why I find theories about ‘the canon is only considered so great because it is the canon’ less than compelling; for half the Great Authors out there I can remember finding them vastly, insistently fascinating well before their names meant anything to me.)

But then the other half of the time, you go look it up and it turns out there’s -- nothing. No one’s ever heard of that author. The full text of the poem isn’t even on google. And so you’re left with these lines that are written as deep in the quiet parts of your mind as this was the funeral of Hector, tamer of horses, only where you expect there to be a shared cultural construct: nothing.

The Terrible Path is one of those. It clung to my brain enough for me to end up making a setting inspired by it. It’s dark and eerie and bizarre, and the sum total the internet has to offer about it is a link from Trinity College that’ll let you download a PDF of the text. I’m not sure why it’s not better-known than it is; I’m no lit critic, but I really think it merits it.

It turns out, the one I was trying to find is another, though this one I at least have a bit of an explanation for.

(2) an odd poem

I ended up having to look it up in the same hard-copy book I read it in the first time, however long ago that was. (How twentieth-century of me, I know.) In this case, that wasn’t technically The Oxford Treasury of Children’s Poems, it was The Oxford Treasury of Story Poems, which has a slightly different selection but is much the same in spirit.

The title is Count Carrots; the author is Gerda Mayer; the one-line note says only from a Bohemian folk-tale called Rübezahl. It’s sandwiched in between Bishop Hatto (the exciting, child-friendly tale of the Wrath of God exacted in the form of the titular bishop being eaten alive by rats) and The Lady of Shalott (Tennyson, also surprisingly weird and dark).

The poem reads like a children’s poem; it’s written in a light, conversational tone. Free verse.

He’s the giant of the mountains;

they call him Count Carrots.

How he hates that nickname.

Let me tell you how he came by it.

Well -- there was that princess

who -- Persephone-like --

had strayed from her companions.

Perhaps you know the story.

(As far as I can tell, that right there? That’s the only place that’s been put online. This poem is nowhere.)

You can probably guess the basic outline of the narrative, just from that quote. The execution, though, is -- something else. The giant gets these odd little humanizing touches --

Some say he brought her gifts of precious stones

to tempt her to love him. This is untrue,

he was simpler than that. He brought her, I think,

bilberries from the forest, baskets of raspberries,

mushrooms, many sorts, which Bohemia excels in,

and clumsy importunings, day after day.

And there are beautiful morsels of description, serving no purpose at all but to be there:

The fact is -- to paddle your feet in a mountain stream,

shallow and fast and cold as molten ice, water which rushes and swirls

over white pebbles, -- to paddle your feet in this on a hot day

is pleasant and delightful: to wash in it, day after day,

indubitably cold. So the princess had discovered.

The tone, already, is getting strange. This should be straightforward -- kidnapped princess, evil giant -- but there’s something bittersweet about every part of it: about the giant who’s really trying to please her, about the homesick princess, about her parents --

‘What shall we tell them at home?’

And who will comfort ever

the queen in tears,

the king in despair?

And then it gets weird.

The princess is lonely. The giant brings her a basketful of carrots from his garden, and explains that they’ll be magically transformed into “whomever, whatever, you wish.”

The princess wishes up her puppy and her friends and her retinue, and she’s happy again. (“She was gracious to the giant. She didn’t see much of him.”)

Then, on the third morning, they start to wilt -- her horse first, then her friends -- stumbling, their flesh shrunken, pale, complaining of headaches, dead in a ditch -- and, finally, carrots again.

(This is -- kind of horrifying, right? It’s not just me?)

The princess goes to the giant. The giant promises to bring her fresh carrots each day, to replace them as they wilt. This satisfies her for a while, but then she feels uneasy, so she comes up with a clever escape plan: she worries aloud that the giant might run out of carrots, and begs him to count them. While he’s distracted, she wishes up a pair of horses and a companion and rides home.

The ending is about as bittersweet and strange as you’d imagine from the rest:

Henceforth, the giant was called Count Carrots by all;

a nickname he hates, as I told you at the beginning.

Woe to him who so calls him in mischief. Let the

impudent traveller, shouting his name, beware.

When I was small, I called his name into the forest:

‘Count Carrots! Count Carrots!’ then leapt into bed, half in fear.

He didn’t come for me though. Could it be that perhaps he forgave me?

He loves children, they say. -- May the forest stay green for him ever.

(3) incidental history

If you’re anything like me -- which, I acknowledge, is a bit of a leap -- this leaves you with two questions. One is: what was up with that poem? And two is: why has the internet never heard of it? (There are, after all, all sorts of poem archives online. Why does this one show up nowhere?)

I don’t have a really good answer to either question, but I have one answer, which split between them makes for maybe half an answer to each.

That answer is in the author. Gerda Mayer: Jewish, Czechoslovakian, born 1927.

It doesn’t take much to do that math. She was eleven in 1939, at the start of World War Two, whereupon Czechoslovakia was not such a good place to be a little Jewish girl. Gerda was (though one hates to use the word) lucky enough to find a place on a Kindertransport to England.

She’d stay in touch with her parents, writing them letters -- them still in Nazi-occupied territory, her off in England. Mayer, much later, writes about the experience:

I am on a raft and they are in a choppy sea. I am eleven, possibly just turned twelve, and they cry out to me -- though in the politest possible way -- ‘If you should happen to have a lifeline or lifebelt on the raft, if it is not too inconvenient...’ It is a forlorn hope. Their heads bob on the surface and the waves grow higher and higher.

Reading an excerpt from one of her mother’s letters, you can see what Mayer is talking about:

Under no circumstance do I want you to bother your benefactors who have already done so much for you; but if you should meet someone who strikes you as particularly kind...

Little Gerda never was able to find someone particularly kind. Her mother would die in Auschwitz; her father, in a camp somewhere in Russia. Mayer writes:

My father went hiking without pass-

port or visa and was

intercepted

My sister went mad my mother

went into that Chamber trusting

in God

God picked the bones clean they lie

without imprint or name dear

mother

By this time, at eleven-or-maybe-twelve, Gerda had already been writing poetry for some time, and shown a distinct talent (though notable, perhaps, only to her parents as yet). Her first poem was written at age four (as any number of biographies available online attest), and saved by said parents in a “Baby’s Diary”.

(None of the online sources include a copy of the poem, as far as I can tell, but full scans of the diary are available online via the Center for Jewish History Digital Collections. My German might be up to the task of translating a four-year-old’s poem, but unfortunately it is definitely not up to deciphering her father’s cursive. If anyone else wants to give it a shot, pages 117 to 124 are dated from 1931-2, when she would have been four, so it should be somewhere in there.)

In any case, Mayer herself says that her poetry suffered severely as a result of the change in language. In a letter written at the request of, and published in, a poetry magazine, she says:

I was born in the Sudeten, the once-German-speaking part of Czechoslovakia. I came over at the age of eleven and, as I was surrounded by English speakers, my reading had caught up with my own age group before three months were out. In any case, I was reading Browning’s Pied Piper to myself and, came the summer holidays, What Katy Did. Conversely, my mother, in a letter from Prague, fretted that my German was deteriorating.

If I had caught up linguistically, poetically there was a time-lag. My first English poem, written at the age of twelve was no better than one I had composed (in my pre-literacy days) at the age of four (proud parents had entered this into my ‘Baby’s Diary’) and a poem I wrote at the age of sixteen was on a level with one I had written at the age of eleven, just before leaving home.

This seems to me the most satisfying explanation available for why Mayer never became more famous than she has. It really doesn’t seem to be a lack of skill; the introduction to her Wikipedia article has Britian’s poet laureate praising her as a fine poet “who should be better known.”

Rather, Mayer is limited by writing in a second language (and one she learned late, at that -- eleven is old to be learning a new language). She compensates for this to some degree for writing children’s, and childish, poetry, where maybe a gift for vivid imagery and tone can compensate for the linguistic handicaps of writing in a second language (poetry! in a second language! I can’t get over how impressive that is to do at all).

Hence we have Count Carrots, which is effective partly because it’s really an adult poet, writing about adult topics, but using the format of children’s poetry; hence also we have commentary on her repertoire like this from Peter Lawson:

Although some of Mayer’s poems are aimed specifically at children, other collections feature what Peter Porter describes as ‘children’s rhymes for grown-ups’. Such poems juxtapose, in the lilt of nursery rhymes, the tentatively self-assured perspectives of children with adult knowledge of the murder of innocents in the Holocaust.

And Mayer absolutely makes this work for her. A characteristic ‘children’s rhyme for grown-ups’:

Grandfather’s house rose up so tall,

Its steps were like a waterfall

It had a deep stairwell, as I recall.

And down the banisters slid my mother,

And her sisters, and her brother,

And many a child, many another.

The banisters wobbled and down fell all.

Down down, down, and beyond recall.

And so I was not born at all.

Better it is not to have been,

Than to have seen what I have seen.

So deck their graves with meadow-green.

Or again:

The children are the candles white,

Their voices are the flickering light.

The children are the candles pale,

Their sweet song wavers in the gale.

Storm, abate! Wind, turn about!

Or you will blow their voices out.

Mayer gets compared to Plath (doing her an injustice, I think, but I’m not overly fond of Plath) and to Blake (much fairer, in my opinion). But she’s nothing like as famous as either -- will probably never be famous, except for her story -- and I think that can be chalked up to the linguistic hobbles she’s working under.

But those don’t prevent her from writing truly great children’s poetry -- and Mayer knows that, and the Oxford editors, evidently, knew that, because the strange beautiful haunting Count Carrots somehow made it into my book of children’s verse.

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mind Sets, a show of seven artists, Jessica Alazraki, William Clements, Donna Festa, Rosalie Frankel, Linda Larsen, Noah Saterstrom, and Gerda Van Leeuween, curated by Lynne Stone. The exhibition opens at Green Kill on Saturday, February 3, 2018 from 5 to 7 pm, and runs from February 3 to February 27, and is open Tuesday through Saturday from 3 to 9 pm.

Mind Sets celebrates seven painters, each singular in expression, each committed to a bold, playful, rude, sad, surreal, sensual, or revelatory vision of the aesthetic mind.

Linda Larsen, “Lookout ( from Sights Unseen series) “, 2013, Oil on canvas, 11″ x 19”.

Gerda Van Leeuwen, “Gassworks #1”

Jessica ALaraki, “Open Door “, 2017, Oil on canvas, 48″ x 60”.

About the Artists

Jessica Alazraki. Jessica Alazraki’s figurative portraits convey everyday stories of colorful characters. These are confronting the viewer, without interacting with each other, instead submerged in their own personal psyche. The narratives are based in ordinary and familiar scenes of Latino family life, highlighting the influence of American culture and implying indirect political statements. The strong presence of primitive and naïve style connects the works to folklore elements and Mexican crafts.

William Clements will feature his monotype series Far Afield. Berkshire based artist William Clements studied printmaking at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois before heading to the New York Studio School to study sculpture. Drifting down to North Carolina, he worked with an experimental MFA program at Western Carolina University. After several years teaching and showing in North Carolina, Clements gave up his adjunct gigs and relocated to the Berkshires in 2012. He worked as a curatorial specialist with EB Fine Arts on their Curatorium gallery project in Hudson, NY, and as a chef at Jacob’s Pillow dance festival in Becket, MA. He currently lives and works here and there.

Donna Festa says about the works she is exhibiting, “We all have them. Those heavy burdens that we carry with us, making our shoulders droop. We push them down, far away from the surface, try to bury them with food, drink, pills. Meanwhile, they make our hips wider, our hair grayer, our worry lines deeper. Life can so easily break us”

Rosalie Frankel says about her work that it’s “an attempted examination of undeniable confusion inherent in the dichotomy between mirth and melancholy.

I am exploring the lively stew of relationships as well as emotions.

My art is the vehicle to expose both the glory and struggle of Eros.”

Linda Larsen will present Entanglements, her multi-media film with Linda Larsen, Constance Humphries, Adam Larsen, and Kimathi Moore, and artworks featured in Entanglements and her Sights Unseen series.

The mysterious Sights Unseen paintings made in 2013 came from my waking dreams over many years. As I worked, I found myself in strange territory and felt I needed a deeper understanding of the recorded history of the slave trade, the middle passage, slave narratives, Jim Crow, and the ongoing civil rights struggle. I read as much as I could, including the incredible novels of Richard Wright, Toni Morrison and Zora Neale Hurston. I also found the writings of historian, Craig Stevens Wilder; Detroit activist, Grace Lee Boggs; social justice and human rights professor of law, Bryan Stevenson, and many more thinkers and writers, too many to count, who brought insight to the intuitive narrative I had begun. Most of the reading was hard to bear.

Gerda Van Leeuwen will present her “Gasworks” paintings. Gasworks is a series of 6 small paintings, monoprint/paint on paper to canvas, 10×6 inches, These series are a result of her wandering the center street of Merida, Mexico. Observing small details on the walls of houses. The rectangle crevices in the walls with almost identical city gas meters but all painted, painted in different ways. Done in 2017.

Noah Saterstrom presents selections from his Sunworshipers paintings. The imagery in these paintings is heavily influenced by my ancestral roots in Natchez, Mississippi. I specifically draw from memoirs recounting the family fleeing during the Civil War to the little town of Shubuta. Themes vary but repeating motifs include a family on the move, houses and landscapes, classical statuary, a fountain, wagon mules, a lion-like creature, suns, and celestial eyes.

Mind Sets Mind Sets, a show of seven artists, Jessica Alazraki, William Clements, Donna Festa, Rosalie Frankel, Linda Larsen, Noah Saterstrom, …

0 notes

Text

Team Favourites: Sixteen Summertime Stories

August is here (!) and while some people think that summer is nearly over, I think the best is yet to come, and I intend to fully squeeze every ounce out of summer. A glass half full approach. : ) So to celebrate the finale to the season, I wanted to share the team’s sixteen favourite summer themed picture books.

A reason to curl up in a shady spot and read is always great. But long summer days are an especially good excuse to add new books to your repertoire. Actually while working on this post, I was so inspired by the recommendations that I purchased a few of the books… (ok, I actually bought five of the books!). The ocean and beach themed books I bought are now tucked away in our suitcases so I can surprise the kids with new books when we arrive at our holiday by the coast. A great way to start our holiday — reading an ocean themed book, curled up on a beach blanket, with sand in your toes, as the sun slowly sets. It doesn’t get much more summery than that!

Enjoy our team’s (family) favourites, with a selection for all ages too. And we hope that these books add to your memorable and magical summer.

Mama Is It Summer Yet? by Nikki McClure. The perfect celebration of summer, this most favourite of seasons! (More detailed review here.) — Courtney

The Flower’s Festival by Elsa Beskow. A perfect book to be read on a midsummers evening. — Vanessa

Miss Rumphius by Barbara Cooney. A tale of living by the sea and doing something to make the world a more beautiful place, this was a favorite book from my own childhood and one I love sharing with my children as they spend part of their summer on a coast that looks much like the one in the book. — Shannon

Make Way for Ducklings by Robert McCloskey. Because I used to go to Boston every summer to visit family, this classic children’s book reminds me of rides on the Swan Boats and time spent in the Boston Common. — Lara in London

Roxaboxen by Alice McLerran. A wonderful story of the intricate worlds children create for themselves with little more than found objects and their imagination. Perfect summer inspiration! — Shannon

The Sand Horse by Ann Turnbull. This book holds very special memories for me and I always read it to my kids right before our annual trip to Cornwall. Set in St Ives an artist sculpts a beautiful horse from sand but when the crowds of tourists have gone home the horse longs to join the white horses of the sea. Its a really touching story and is beautifully illustrated. — Kate

The Little Island by Margaret Wise Brown. Another tale of changing seasons and observations of nature on a little island in the sea. I love the charming illustrations! — Shannon

The Swing by Robert Louis Stevenson. Such a romantically sweet book for young children. I love the illustrations. —Vanessa

ABC: off to Sea! by Virginie Morgand — Lara in Paris

Summer by Gerda Muller. Part of a series, these no-text picture books that celebrate the seasons are simply adorable in a very timeless way. My kids love them! — Esther

Magic Beach by Alison Lester — When the beach becomes the perfect setting for all sorts of imaginative adventures. We love this beautiful rhyming book. Courtney

Time of Wonder by Robert McCloskey. All of Robert McCloskey’s books are great, but I think this is my absolute favorite. It traces the passage of a summer on a little island off the Maine coast, and McCloskey’s descriptions and illustrations are stunning. — Shannon

Harry by the Sea by Gene Zion. Harry the dog goes to the beach with his family and chaos ensues. A super charming summery story. (Detailed review here.) —Courtney

In One Tidepool by Anthony D. Fredericks. On a recent trip to Laguna Beach we bought this book. It is fascinating. — Lara in London

Blueberries for Sal by Robert McCloskey — I think of this book every time I go berry picking! A classic Caldecott Honor story of a little girl, Sal, and her mother on a blueberry picking outing. Vanessa and Courtney

The Curious Fish by Elsa Beskow. Such a charming and curious book. Perfect to read on the river bank with a picnic! — Vanessa

We would love to hear your family summer favourites too! Let us know.

Lara

The post Team Favourites: Sixteen Summertime Stories appeared first on Babyccino Kids: Daily tips, Children's products, Craft ideas, Recipes & More.

from kid games toys http://ift.tt/2vnPMl9 via kid games toys

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Sgatach di Gerda Stevenson

Sgatach di Gerda Stevenson

Gerda Stevenson, attrice, regista e scrittirce scozzese (1956)

Sono un’ombra, solo un mormorio, ora,in cori sparsi di lingue,pur se ancora la luce del sole infrange le ondenell’arco del mio castello in frantumi,come i coltelli che io insegnavo a Cu Chulainn a scagliare;oltre la baia, s’ergono ancora i Cuillin, là dove un tempoil sole vibrò una lancia; rupi scure ch’artigliano il cielodi gabbro…

View On WordPress

0 notes