#gettysburg (1993)

Text

I can't do edits for the life of me.

I tried to do one of Lawrence and Tom but couldn't find a template 😔😔😔

So here's what I got!

He's just chilling

#american civil war#acw#civil war#gettysburg (1993)#gettysburg 1993#tom chamberlain#thomas chamberlain

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

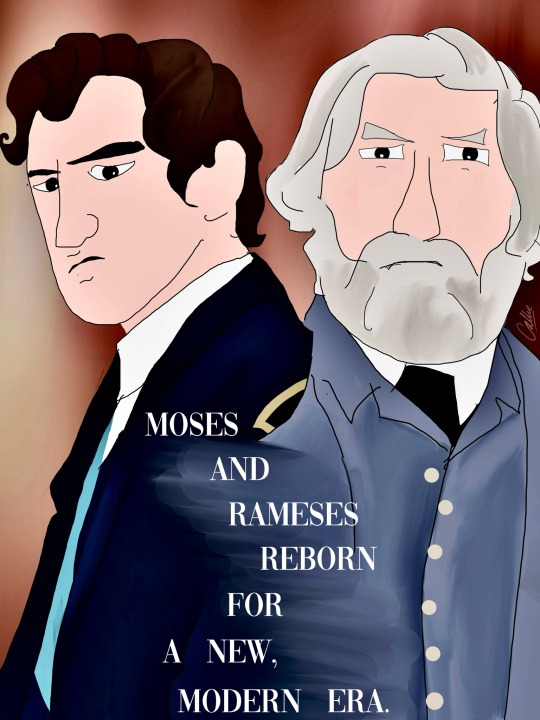

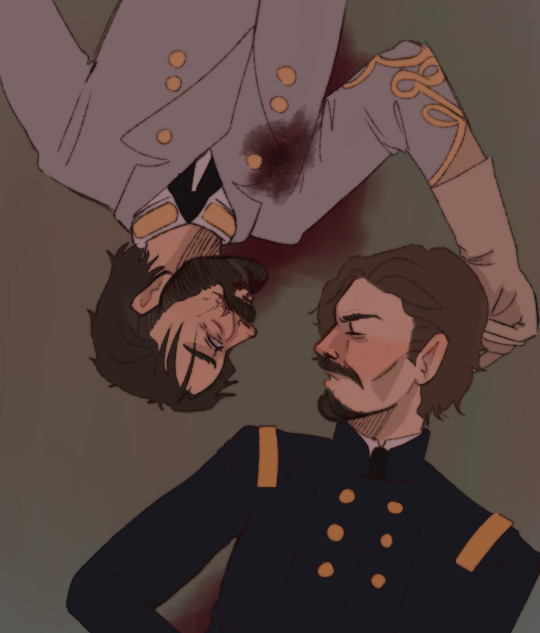

❝ In Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his wayward brother, Union Lieutenant General Ethan Clay, the heart of the Civil War found its human personifications. It was, after all, a war between brothers — and here were the biblical Moses and Rameses reborn for a new, modern era. ❞

I smell a civil war tumblr revival in the works … and I’ve been meaning to draw the Lee siblings in honor of this year’s Appomattox anniversary… so I made this instead of working on an essay that’s due tomorrow 😜

#original character#acw#gettysburg 1993#american civil war#* original characters#* callie’s art#* american civil war

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Umm… uh…. I noticed there was some Lofield Hanistead content going around, so I thought, why not?

Y’all can bully me this is terrible hivtkhvf

#american civil war#acw#gettysburg (1993)#gettysburg 1993#winfeld scott hancock#lewis addison armistead#tommy’s art#shitpost#history memes

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

*talking on the phone*

Kilrain: Remember how I said that Tom and I were gonna have a calm night out for once?

Chamberlain: Yeah…

Kilrain: Well, we’re in jail.

Chamberlain: *hangs up*

#maine men phenomenon#buster kilrain#tom chamberlain#joshua lawrence chamberlain#gettysburg incorrect quotes#gettysburg 1993

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just came across an article from the INVERSE website that complained about Hollywood movies with a long running time. The author, Dais Johnson, had focused the article's complaint on Ridley Scott's new movie, "NAPOLEON". But this complaint about movies with long running times and no intermissions began with the release of Martin Scorsese's new movie, "KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON".

My question is . . . why now? Why complain about long running times with no intermissions . . . now? The last long movie I had seen with an intermission was 1993's "GETTYSBURG". But that was a rare occasion. The last official Hollywood movie to offer an intermission was the 1982 movie, "GANDHI".

After the latter film, intermissions for a long movie had become increasingly rare. And the complaints become increasingly rare . . . until now. Why did it take "KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON", of all movies, for the media to bitch and whine about a movie's running time and no intermission?

#anti media#long movies#ridley scott#napoleon 2023#martin scorsese#killers of the flower moon#gettysburg 1993#gandhi 1982#long running times#intermission

0 notes

Text

shoutout to dan sickles for not being in gettysburg (1993) maybe it’s for the better

#gettysburg (1993)#american civil war#acw#…here we go#john reynolds#john buford#arthur fremantle#james longstreet#george gordon meade#daniel sickles#winfield scott hancock#george pickett#tom chamberlain#joshua lawrence chamberlain#jeb stuart#lewis armistead#robert e lee#shitpost#you can tell there’s a quality drop on some of these

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gettysburg Washington, D.C.Premiere

Stephen Lang attends an event at the National Theatre in Washington, D.C. on October 4, 1993.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bobby’s gonna have to shut you down on that one Pete

#gettysburg#movie: Gettysburg (1993)#dumb gettysburg shitposts#james longstreet#bobby is gonna have to be a 'stop' sign up in longstreet's face everytime he comes around with an idea#very silly post lol#spoiler alert: ewell does not take the hill#robert e lee#also so funny to watch this scene and the amount of times the lighting changes#goes from middle of the day to sunset then back to middle of the day real quick#also i noticed that 95% of these dumb posts i make are lee and longstreet....whoops?

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

my favorite ghost story that isn’t particularly creepy is the one about gettysburg 1993 that one is so like. it means something. to me. idk what but it’s meaningful

304 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m just a defense analyst, so I’ll leave a proper critique of Ridley Scott’s new blockbuster biopic Napoleon to the many reviewers who have already disparaged it. I, for one, found it to be a lukewarm mélange of battle scenes and romantic vignettes, leaving me with neither a sense of the man Napoleon Bonaparte—the bicorne-hatted soldier-turned-emperor of the French—nor a feel for the age of upheaval he so much defined. For a grand piece of historical fiction from the director of such masterpieces as Blade Runner, Thelma & Louise, and Black Hawk Down, the film curiously fails to entertain.

My perspective on Napoleon is a different one. Scott’s film stands in a long line of movies, novels, and even history books that have given the world an entirely wrong view of how wars are fought—and even more importantly, how they are won. And that matters, because the mythical idea of war embedded in Napoleon and so many other works has become so widespread in our culture and discourse that it ends up informing actual decisions about actual wars.

Let’s call it the decisive battle myth. Napoleon, with its focus on famous battles such as those of Austerlitz and Waterloo, perpetuates the dangerous idea that wars are decided by great and bloody clashes. This obsession is as old as there have been written accounts of history, but in popular culture in the English-speaking world, the myth can be traced back to the 1851 publication of The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World: From Marathon to Waterloo, which helped kickstart an entire genre of works focusing on battles supposed to have singlehandedly changed the course of history. In film, think of The Longest Day, Midway, and Stalingrad; in books, the list of battle histories and battle fiction is too long to contemplate. The genre even plays in counterfactuals: The 1993 movie Gettysburg, based on Michael Shaara’s novel The Killer Angels, suggests that the South could have won the U.S. Civil War had the Battle of Gettysburg gone the other way.

No matter what these works have taught us to think, the decisive battle is a myth. Wars between major powers are not decided by great battles but by attrition of soldiers and materiel, which in turn is determined by such things as force size, logistics, production, and technology. Battles, large and small, are important only to the extent to which they accelerate attrition and wear down the other side. Yet the myth of the decisive battle—the idea that an adversary can be defeated in one big and bloody but short engagement—remains powerful. It’s also dangerous, because it affects not only ordinary moviegoers but military and political leaders as well. In other words, the very people deciding whether to start and how to fight a war.

Scott’s focus on battles is hardly surprising. Napoleon fought numerous campaigns culminating in big set-piece battles, after which the defeated side sought peace; at the Battle of Austerlitz, Napoleon defeated the allied armies of Austria and Russia, forcing the former to sue for peace and the latter to retreat home. But the French emperor’s most celebrated victory—exactly 218 years ago today—was only an episode in a long war that did not end until 10 years later, after attrition and mutual exhaustion.

The focus on decisive battles orchestrated by a brilliant military leader such as Napoleon has been poisoning Western military thinking for centuries by suggesting that great power wars can be short affairs. The idea that an adversary can be decisively beaten in just one or a few engagements has incentivized political and military gambling: Think of the German Schlieffen Plan that bet on a single, decisive encirclement of French forces and their quick annihilation or capitulation in 1914, with the disastrous result of condemning much of Europe to four years of attrition with millions of soldiers killed. The idea of a quick, decisive battle inspired then-Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein to invade Iran in 1980, which led to a horrifically bloody eight years of attrition.

More recently, Russian President Vladimir Putin thought one decisive push toward Kyiv in early 2022 would quickly and painlessly conquer Ukraine. Hundreds of thousands of deaths later, the grinding war goes on. For all the emphasis on Napoleon’s quick campaigns and decisive battles, his wars tell a similar story of long and painful attrition: More than 5 million European soldiers were killed or otherwise died during the Napoleonic wars, a level of carnage, relative to total population, on par with World War I. France alone lost around 860,000 soldiers, including 38 percent of all men born between 1790 and 1795.

That Napoleon is only a movie doesn’t make it better. There are documented cases of films influencing a policymaker’s decisions to go to war. In 1970, for example, then-U.S. President Richard Nixon repeatedly watched the film Patton during the decision-making process to expand the Vietnam War into Cambodia, taking inspiration from the movie general’s willpower and single-minded belief in U.S. military power. One academic study found that popular culture, including fictional films, can frame the way we think about a multitude of issues, and there is no reason to believe that military officers and policymakers are exempt from these effects. Movies can help prevent wars, too. Former U.S. President Ronald Reagan was inspired by the television film The Day After and Tom Clancy’s novel Red Storm Rising to push for nuclear arms control. But if decision-makers and military leaders are prone to fighting the wars of their imagination, then a popular culture that reinforces the idea that wars can be short and decisive may incentivize willingness to look for a quick military solution to a political problem.

There is much more in Napoleon that made me cringe as a military analyst. What you see on the screen has absolutely nothing to do with warfare in the age of Napoleon—as a matter of fact, the clouds of gunpowder from the era’s muzzle-loaded muskets meant you would not be able to see very much on a Napoleonic battlefield to begin with. The battle scenes are a Hollywood mishmash of medieval melees, meaningless cannonades, and World War I-style infantry advances.

One scene that stands out is the apocryphal depiction of Napoleon leading a cavalry charge into what are supposed to be the Russian lines at the Battle of Borodino. As a former artillery officer, of course, Napoleon never led a cavalry charge in his life. For all of Scott’s fixation on Napoleon’s battles, he seems curiously disinterested in how the real Napoleon fought them—and just as disinterested in the changing character of Napoleonic warfare. By 1812, Napoleon’s enemies had not only learned to adapt by emulating the French style of fighting, but the battles themselves had turned into meat grinders of such a scale that no individual could control them. The battles of Wagram (in 1809), Borodino (1812), and Leipzig (1813) each involved hundreds of thousands of troops and many hundreds of cannons. The idea that the commander of his country’s armies in an 1812 battle had the liberty to lead a horse charge is so preposterous that the scene makes Mel Gibson’s Braveheart—considered one of the most historically inaccurate films in recent decades—look like a paragon of historical realism.

Napoleon’s military genius was not just about individual heroism or skilled battle tactics, but more importantly his vision for structural reforms. Napoleon helped institutionalize the corps system, dividing up large armies into smaller ones as a way to enable more effective command and control, as well as greater speed and range. Key to this new corps system were Napoleon’s marshals, distinguished military officers who sometimes remained undefeated in battle and whose deaths Napoleon mourned deeply. It was the marshals and other officers to whom Napoleon delegated authority; they proved to be a major asset contributing to his victories. In the film, these colorful independent actors are relegated to the role of footmen.

The film’s wild inventions go much farther. The British Army, led by the Duke of Wellington, features prominently, even though it played only a minor role in battle. Rather than the fighting role, the British contribution to Napoleon’s defeat lay in the sea blockade and in financing the huge standing armies of Austria, Prussia, and Russia that bore the brunt of the fighting. The duke and Napoleon never met in person, another invention of the movie that could have been omitted without loss, since it is devoid of meaningful dialogue that might have helped the audience better understand Napoleon’s volatile and ruthless character. Scott could instead have depicted the heated argument between Napoleon and Austrian diplomat Prince Klemens von Metternich during their famous eight-hour encounter in Dresden, then the capital of the Kingdom of Saxony, in 1813. The meeting convinced Metternich of the French emperor’s troubling mental state and the impossibility of making peace as long as he reigned.

There is no reason to believe that the myth of the decisive battle will lose its power any time soon. As the historian Cathal J. Nolan writes in The Allure of Battle: “The idea of decisive battle will always be more alluring than winning by attrition—morally and aesthetically; to generals and theorists, and to publics hungry for war news.” Nolan might have added film directors to his list.

Let us hope that U.S. and NATO military strategists and force planners do not draw too deep an inspiration from Scott’s depiction of Napoleonic battle. It’s bad enough that the allure of the decisive battle is already shaping U.S. deliberations over how to fight a possible future war with China over Taiwan. Disregarding the likely attritional character and extended length of such a fight—and the requirements in manpower, weapons, ammunition, production capacity, and political constancy that would entail—could spell disaster for the United States and its allies. Focusing on long attrition instead of dramatic clashes would certainly make for a boring film experience, especially since one only has to look at Ukraine to see the long slog of attrition playing out in real life. Nonetheless, stripping Napoleon of the romanticism associated with epic battles decided by the archetypal hero on horseback would be a small first step in gaining a better understanding not only of past wars, but also of how future wars will be fought.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

I changed my profile photo to depressed Pickett for my Gettusburg-sona 🎉🎉🎉

(Please ignore Confederate flag, I did not ask it to be in this frame :( )

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gettysburg (1993) - dir. Ronald Maxwell

Martin Sheen as Confederate General Robert Edward Lee

“Lee’s letters force us to embrace a multifaceted man. Lee the flirt, the man handicapped by passivity and indecision, the racial supremacist, the humorless sermonizer, and the merry companion must be conformed with Lee the natural leader, the sentimental lover of children and animals, the indifferent engineer, the aggressive warrior. His words can distress as much as they charm. We cannot compartmentalize him, and we cannot simply lionize him. His letters show him to be too human for that.” - Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters

#Gettysburg 1993#film edit#gifset#robert e lee#american history#history#gettysburg#american civil war#acw#martin sheen#age of jackson#period drama#historical#media: gettysburg (1993)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nobody:

Sam Elliot playing John Buford in Gettysburg:

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tom: I hate to disagree with you, but-

Chamberlain: Please, you love to disagree with me. It's your favorite thing to do.

#joshua lawrence chamberlain#tom chamberlain#chamberlain bros#gettysburg 1993#gettysburg incorrect quotes

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forcing my grandparents to watch all four hours of Gettysburg (1993) directors cut hehe

wish me luck >:D

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

♫♪ trust in god and fear nothing. remember these that i write. for as we make our way, there may come a day where comrades and brothers must fight.

just kidding they’re normal

24 notes

·

View notes