#guiyang city

Text

20230831#Guiyang City #GuanShanHu Park #

物是人非事事休,欲语泪先流。 ——李清照 《武陵春》

回首向来萧瑟处,归去,也无风雨也无晴。——苏轼《定风波》

世事一场大梦,人生几度秋凉?——苏轼《西江月》

多情却被无情扰。——苏轼《蝶恋花》

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

SHAN-SHUI CITY - CHINA

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

想定外の風? (;´∀`) エェェ

This 360 foot-tall building in the city of Guiyang, China, has a tank installed at its base, where four 185-kilowatt pumps lift the water to the top of the fall and create an artificial waterfall.

(Reddit: r/Damnthatsinteresting u/prolific_ideas)

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

This 121-meter-tall building in the city of Guiyang, China, has a tank installed at its base, where four 185-kilowatt pumps lift the water to the top of the fall and create an artificial waterfall. via @Rainmaker1973

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decades ago, Western political scientists began asking a question that has never been fully resolved but has also never seemed more urgent. They noted that since World War II, extremely few countries had joined the ranks of the globe’s truly wealthy nations and almost all that had were already democracies or were in the midst of political transitions that would lead to systems that gave citizens a choice in the selection of leaders. So, they wondered: Could China, the world’s largest country—and, since the Soviet Union’s demise, the most powerful and, in aggregate terms, richest authoritarian society—buck the trend?

If it failed to do so, China would be said, in the jargon of experts, to have succumbed to the middle-income trap: a theoretical snare awaiting countries that failed to liberalize their political systems no matter how successful they had appeared during an early phase of economic takeoff.

Chinese President Xi Jinping has been mindful of this challenge and at times has even boasted about his country’s ability not only to break this mold of notional constraints but also to prove the superiority of his version of authoritarian rule. Now, no sooner than Xi has engineered changes in China’s leadership succession rules so that he can preside over his country for life, a crisis that may come to be seen as an ideal test of the middle-income trap theory is upon him.

Its proximate cause appears to have been an apartment block fire in the far western Chinese city of Urumqi that killed 10 people. It reportedly took firefighters more than three hours to put out the blaze, which local officials said was caused by a faulty power strip, causing many on social media to speculate that the city’s ongoing strict COVID-19 lockdown measures may have hampered the response and prevented residents from evacuating. Chinese authorities have denied this and even suggested that blame lay with the apartment dwellers for being slow to flee.

The shocking news of this incident has set off the most serious political protests in China since the 1989 Tiananmen Square crisis, with Chinese people in a rapidly growing number of cities—including the place where Xi himself studied in Beijing, Tsinghua University—coming out in the streets by the thousands to hold up blank sheets of paper, symbolizing censorship, and braving arrest as they chant recently unimaginable slogans such as “Step down, Xi Jinping! Step down, Communist Party!” and “Don’t want dictatorship, [we] want democracy!”

Yet as tempting as it will be for many, it is wrong to see this crisis as solely the result of a spark from Urumqi. This challenge to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the state has been building for some time. The country’s unusually strict and prolonged campaign to contain the COVID-19 pandemic has been a source of deep discontent for many months, leaving many Chinese people feeling disenchanted with Xi, who seems more obsessed with control than any leader since Mao Zedong.

After a previous incident in September involving the crash of a bus carrying people from the locked-down city of Guiyang to a quarantine camp, which killed 27 people, the number of messages I began receiving from friends in China that spoke of wanting to leave the country or mentioned stories of others who had already escaped skyrocketed. That may seem merely anecdotal, but what happened next was anything but.

On Oct. 13, on the eve of the Party Congress in Beijing where Xi effectively coronated himself—and amid high, citywide security—a man hung large protest banners on Sitong Bridge, which passes over a major central thoroughfare, denouncing not just the country’s zero-COVID policy but also Xi’s dictatorship, censorship, personality cult, and suppression of human rights. The banners read:

We don’t want nucleic acid testing, we want food to eat;

We don’t want lockdowns, we want freedom;

We don’t want lies, we want dignity;

We don’t want Cultural Revolution, we want reform;

We don’t want [dictatorial] leaders, we want elections;

We don’t want to be slaves, we want to be citizens.

In an echo of the famous Tank Man of Tiananmen, the man was arrested and reportedly has not been seen or heard from since. State censors made furious attempts to remove mention of the protest from webpages and social media, but the intensity of interest overwhelmed them.

The next highly unusual occurrence happened during the Party Congress itself, when Xi’s predecessor as CCP general secretary, Hu Jintao, was ushered off the main dais at a critical moment during the proceedings. Hu had just reached for a folder that is thought to have contained the final list of the members of the Politburo Standing Committee, the highest instance of power in the country after the general secretary. One theory is that Hu suspected that Xi had not respected commitments to allow people other than his closest personal allies to sit on the body, erasing past practices of relatively collective rule. Another leader prevented Hu from opening the folder, and then Xi gave the signal for him to be unceremoniously led out.

While it may be impossible to know exactly what transpired, many people in China responded with shock, as if they had finally realized how deep the country had descended into a new stage of despotism. Again, many friends in China wrote to me, asking what I had heard and writing that they could not afford to say anything, except to deplore the overall situation in the country.

Although the details of these recent events are unique, some of their contours bear strong resemblance to previous crises in the country. Take, for instance, the 1989 Tiananmen crisis. Although Deng Xiaoping, as paramount leader, eventually approved the murderous crackdown on the student and worker demonstrators who filled the square, he later said privately that it was “very unhealthy” for “the destiny of a country to be built on the prestige of one or two people.” Not since Mao has China been so dominated by a single figure as Xi.

Even worse, under Xi, at each hint of crisis, whether economic—as with the pandemic-induced slowdown or a real estate bubble—or now political, instead of the liberalizing reforms his country and its broad middle classes need and hope for, Xi has reflexively become even more sternly top-down and authoritarian in his response. This ominously echoes his famous comment about the end of Soviet rule under Mikhail Gorbachev in which Xi said the Soviet Union’s Communist rulers lost their nerve, meaning that they failed to rule without flinching and to crack down on opposition mercilessly when necessary.

No one knows what is in Xi’s mind, but he is surely aware of the example of Zhao Ziyang, his predecessor decades ago as CCP general secretary during the Tiananmen crisis (a position under Deng). Zhao, in that much simpler and poorer time, had warned that “reform includes reform of the economic system and reform of the political system. These two aspects affect one another. … If [political reform] lags too far behind, continuing with the reform of the economic system will be very difficult, and various social and political contradictions will ensue.”

Zhao had envisioned clear separations between the role and authority of the party and the government; much more independence for the country’s courts; an end to the purely rubber-stamp function of the country’s parliament; increased freedom of speech and of the press; and even a greater role for the country’s tiny, authorized alternative political parties. He and his allies argued that if the people were not granted freer expression, society would have no pressure valve, practically guaranteeing explosive crises in the future. Xi seems to have never thought well of any change that might reduce the CCP’s power, but it seems likely that even he knows that at some point China’s political system will have to adapt for the country to continue to modernize and escape the theoretical middle-income trap.

His problem, like that of so many leaders who concentrate immense power in their own hands, is that no moment ever quite looks like a good one to make serious, substantive change. The difference between Xi and Deng, who had previously long been considered the country’s most powerful ruler since Mao, is that Deng always took care to have high-profile politicians executing decisions and implementing policy in the foreground. Under Xi, who seems to utterly dominate every important committee and instance of power himself, there is no one but the great leader himself. When the Tiananmen crisis broke, Deng could blame Zhao—and did. Xi, however, has no meaningful deputy or surrogate and therefore has no one else to blame.

This places him in the teeth of an altogether different trap. If he orders his troops and police to execute a heavy-handed crackdown on a fed-up and networked citizenry, things could get bloody quickly, as with Tiananmen—with grave consequences not just for his relationship with his people but also for China’s place in the world. It is even possible that some of his commanders could refuse to execute his orders, as at least one principled general named Xu Qinxian did during Tiananmen.

On the other hand, if Xi abruptly changes strategy and puts on the garb of a supple moderate, people both within his system and without may decide that he is weak and vulnerable and become emboldened to mount bigger challenges to his authority.

One way or another, China is poised on an uncomfortable fulcrum right now, and it will have to choose a course.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guizhou's first furcon finished with 200 attendees

中文:中国贵州首届兽展以 200 参会者成功落幕

QianFurCon (QFC), the first furry convention held in Guizhou, China, debuted with the theme “Midsummer Tree Shade”.

They welcomed some 200 furries across the country for a furry weekend at Guiyang City’s Wanyi Panorama Hotel on Aug 3-4, 2024.

QFC 2024’s event floor plan and vendor list.

QFC featured a single-floor layout as their main event space. First, whiteboards…

0 notes

Text

Music injects vitality to Guanshanhu District, southwest China’s Guizhou Province

GUIYANG, CHINA – Media OutReach Newswire – 20 August 2024 – Guanshanhu is a modern urban area in the capital city of Guiyang, southwest China’s Guizhou Province. It integrates ecology, culture and economy, and boasts rich tourism resources and powerful urban functions.

Music Festival held in Guanshanhu District, Guiyang city, Guizhou Province, China

In recent years, Guanshanhu, one of the core…

0 notes

Text

China's Infrastructure LEADS the World (Americans in Shock) - YouTube

youtube

In this video, we take a look at China's amazing infrastructure and how it's far surpassing America's in terms of design and construction. China's amazing infrastructure is making America jealous, and many Americans are in shock. They won't believe it!

This is Guiyang city in Guizhou province. Guizhou is actually one of the poorest provinces in China but it can still embaress America. Guizhou is a very mountainous region and is famous for it's world class bridges, highways and tunnels. America just can't compete.

0 notes

Text

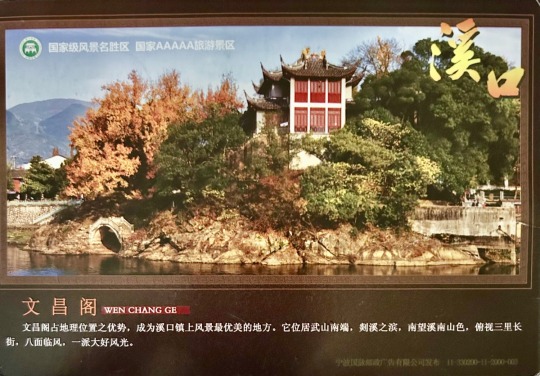

Wenchang Pavillion

Postcard from China

Wenchang Pavilion is located in the old east gate site in Guiyang city. It is a three-story pagoda-shaped building. Because the corners of the cabinet buildings are all even-numbered equal angles, the Wenchang Pavilion with nine corners has become a unique and ancient building that is as famous as the Jiaxiu Building. The building is simple and majestic.

Tuesday Take Me To…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

YOU ONLY LIVE ONCE SWAG

고마우잉 마음이 흐뭇하고 즐겁다

( 99% 노력과 1% 의 운)

❤^^♡

Experience is the best teacher

Life is not a matter of speed but direction

I never give up

Dream comes true

Power of imagination

For your experience Over the limit

Just do it

2024 NUST

PULL HOUSE MUSICFESTIVAL

NUST IN MARCH 2024 3.23 / 3.24 INFO

CAPACTIY 30.000~50.000pax Each Day

DATE/CITY

3.23-3.24 Changzhou

5.03-5.04 Wuhan

5.01-5.04 Changzhou

6.22-6.24 Guiyang

8.01-8.11 Guangzhou

10.01-10.04 Shanghai

Others Updating

3.23: Patti, Fine band, Tang Jiuzhou, ONER, Yaozheng, Wang Zhengliang, Allen Su, Zhang Yanqi, GALI, AIR, Jessi, Tiger JK & Yoon Mirae, Wang Leehom

3.24: Mr Trouble & Draksun, Diverseddie, Xtina, AThree, Zhang Zining, YuYan, GuiBian, Xiaojingling, FaLao, KeyNG, Tablo, GAI

0 notes

Video

youtube

[4K] Foggy day in Huaguoyuan, Guiyang City, China, morning walk

0 notes

Photo

Guiyang is the capital city of Guizhou province in southwestern China. Known for its pleasant climate, natural beauty, and vibrant cultural scene, Guiyang offers a range of attractions and experiences for visitors.

Jiaxiu Tower: Located on Nanming River, Jiaxiu Tower is a historic landmark and one of Guiyang’s iconic attractions. Built during the Ming Dynasty, the three-story tower features traditional architectural design and offers panoramic views of the city from its top level.

0 notes

Text

Green Roofs and Living Walls Around the World

Green roofs and living walls are a magnificent way to incorporate nature into the urban landscape. As cities grow, these sustainable features have become an important aspect of the fight against climate change. With their breathtaking beauty and numerous benefits, it’s no wonder why green roofs and living walls are becoming more popular.

Here are some of the most famous green roofs and living walls around the world.

High Line in New York City

Garden at 120

In Chicago, the Garden at 120 is a stunning green roof that covers an entire city block. With over 100,000 plants, including trees, shrubs, and grasses, it’s a hub for outdoor events and gatherings.

Sky Garden

Green Wall of China

In Guiyang, China, the Green Wall of China is the longest-living wall in the world. It covers over 4,000 square meters and is made up of a variety of plants, including flowers, grasses, and shrubs.

Green Wall at the Hotel de Ville

Finally, the Green Wall at the Hotel de Ville in Paris is a magnificent living wall that covers the entire facade of the city hall. With over 15,000 plants, including flowers, grasses, and shrubs, it adds a stunning element to the iconic building.

Conclusion

These different projects highlight innovative and sustainable features. They bring greenery and nature into urban environments.

Green roofs and living walls have numerous environmental and health benefits, such as reducing air pollution, conserving energy, and providing habitat for wildlife. These famous examples of green roofs and living walls around the world showcase the creativity and diversity possible with these features. They serve not only as an inspiration for future projects but also as a testament to the importance of incorporating sustainable design into the built environment.

As cities continue to grow and urbanize, green roofs and living walls have the potential to play a crucial role in creating healthier and more livable spaces for communities. They are a reminder of the importance of thinking creatively about sustainable landscape design and the positive impact it can have on the environment and human health. These features have the power to create a greener, more sustainable future for all of us.

Article originally from:

Green Roofs and Living Walls Around the World - IOTA Designer Planters (iotagarden.com.au)

0 notes

Text

18/9/2022 Nie Riming | Not a simple traffic accident, Guizhou bus overturning accident

‘We must see that the Guizhou transfer bus overturning accident is not an isolated case. Many cities are also working in that way when it comes to lockdown regulations, the difference only being that other cities have not yet had an accident. Guiyang is not the first case of transferring people to a quarantine hotel at midnight, but there an accident can happen in one city where more such things are done.’

As the title says, this accident was not just a simple traffic accident. It happened on a transferring bus to take Covid patients to the quarantine hotels. The driver was wearing a protective coat and mask when driving on a mountainous road in the mountains of Guizhou at midnight. He has continuously worked for days and didn’t take any rest. Finally, the tragedy happened.

Q: What’s your memory of this event?

Interviewee A: I think the overload working and the protective coat made the driver can’t breathe is the mean reason for this accident. The ironic thing was, to reach the clear target, the bus was immediately decontaminated. Actually, I just drove from the same road a few days before.

Interviewee B: Yes, I read the news. This was not an accident but murder, it could have been prevented. The fear of failing to achieve the order of reaching zero Covid cases pressured the local officers to use more violent and strict means.

0 notes

Text

Just weeks ago, catching Covid in China meant being taken to government quarantine for an indeterminate stay and your entire residential building being locked down, trapping neighbors in their homes for days or weeks.

Now, as the country rapidly relaxes restrictions, millions of people have been told to keep going to work — even if they're infected.

The cities of Wuhu, Chongqing and Guiyang, and the province of Zhejiang, collectively home to more than 100 million people, all recently issued directives to public sector employees indicating a shift from preventing infection to allowing the resumption of life and work.

Asymptomatic and mildly ill workers can "go to work normally after taking protective measures as necessary for their health status and job requirements," said the Chongqing and Wuhu authorities in similar statements posted on their municipal government websites.

Zhejiang provincial and health leaders gave similar instructions at a news conference Sunday, with one official suggesting key teams consider a rotation schedule "to ensure uninterrupted work and maintain order when outbreaks are severe." Guiyang followed suit on Tuesday, according to state media.

"A few months ago if you went out like this, you would be sentenced," one person commented on Weibo, China's version of Twitter, under the back-to-work announcement.

Bonnie Wang, a fintech worker in Zhejiang's industrial hub of Ningbo, told CNN that a colleague with Covid symptoms continued to work in the office this week with a fever.

"I hope when we encounter situations like this, our health will still come first, and work comes second," she said.

0 notes