#gulag literature

Text

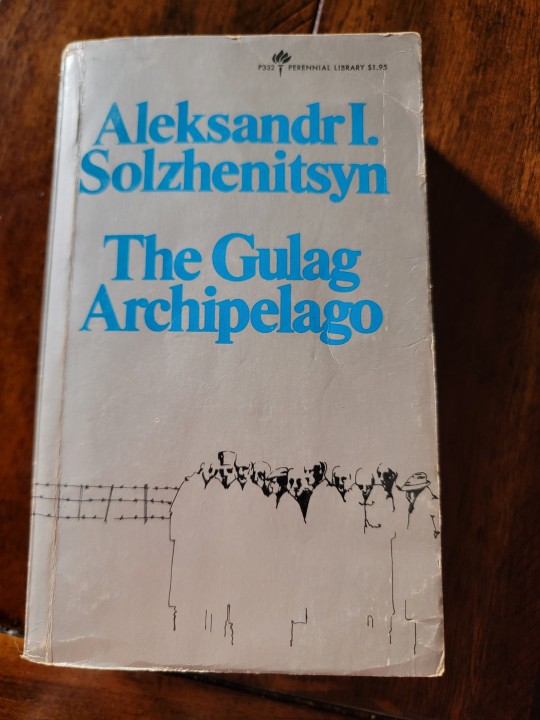

I found this book on one of our bookshelves at home. I like looking through the shelves because there's always a mysterious book I've never seen before. Lately I've been spotting Soviet histories/literature. I found a biography on Stalin, which I found interesting, but not as much as this. I only got a few pages into that to know it probably wouldn't go into a lot of the atrocities. Personally, I like viewing the events through the eyes of the common people, the victims. You don't see that much in history textbooks! So I picked this one up (The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn), the word "gulag" catching my eye:

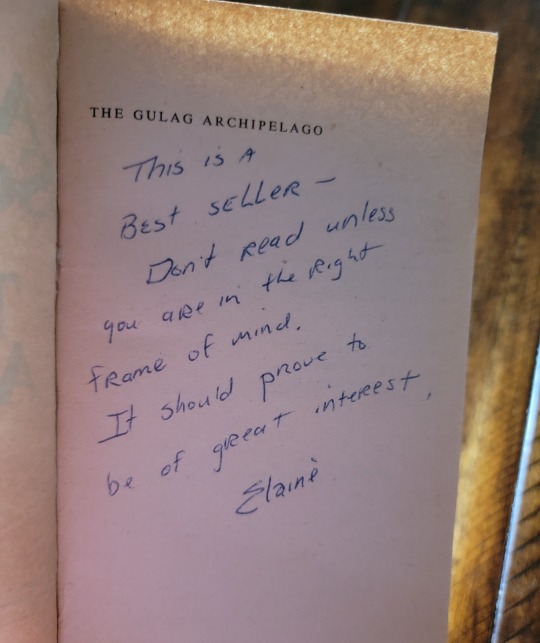

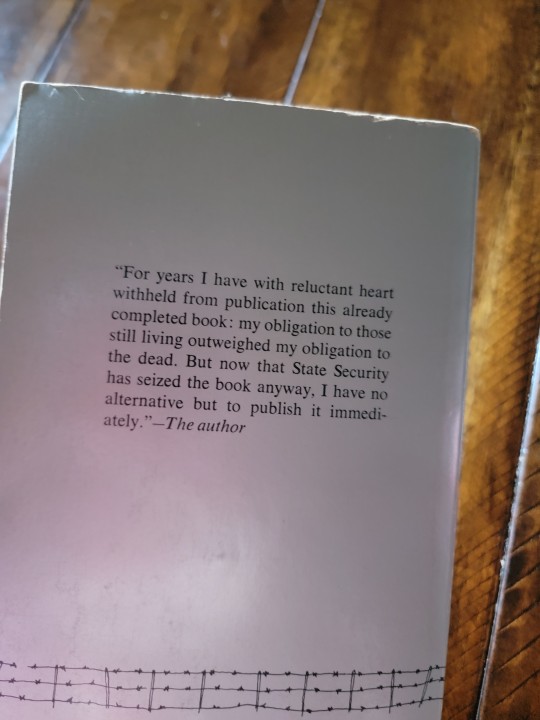

So I flipped it over and opened it, finding an interesting hand written note/warning by a woman who I'm not even sure is alive anymore and an author's note on the back which was also intriguing.

Now I had to read this! Yes, I'm very much in the right frame of mind right now, so Elaine's warning doesn't mean that much to me right now. If you can't read it, I did make alt text for every image I put here.

The book itself is partially researched and partially an autobiography to describe what it was like to be in the Gulag (and how it was to be arrested and such).

This is apparently the first of 3 volumes, though we only have this one. I haven't gotten far in it either; I'm only 10 pages in. But let me say, Elaine was right... Currently it's describing the arrests of citizens, which is traumatizing enough. Knowing the Gulag was even worse is just an eerie experience. I might update my thoughts as I read on, but no promises.

ANYWAY I recommend this book for anyone interested in stuff like this. Even if you're not, you should look into it anyway because I think it's important to learn about just how bad totalitarian governments are (FUCK THE KGB AND FUCK STALIN)

#book recommendations#book recommendation#book#novel#russian novel#russian literature#soviet literature#soviet#soviet union#the gulag archipelago#aleksandr solzhenitsyn#bookblr#booklr#history#literary investigation#elaine#stalin#ussr#kgb

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“… What about the main thing in life, all its riddles? If you want, I'll spell it out for you right now. Do not pursue what is illusionary -property and position: all that is gained at the expense of your nerves decade after decade, and is confiscated in one fell night. Live with a steady superiority over life -don't be afraid of misfortune, and do not yearn for happiness; it is, after all, all the same: the bitter doesn't last forever, and the sweet never fills the cup to overflowing. It is enough if you don't freeze in the cold and if thirst and hunger don't claw at your insides. If your back isn't broken, if your feet can walk, if both arms can bend, if both eyes can see, if both ears hear, then whom should you envy? And why? Our envy of others devours us most of all. Rub your eyes and purify your heart -and prize above all else in the world those who love you and who wish you well. Do not hurt them or scold them, and never part from any of them in anger; after all, you simply do not know: it may be your last act before your arrest, and that will be how you are imprinted on their memory.” — Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago

#text#literature#this book is so thick but truly a well of wisdom#also the fact that this dude wrote this novel in his head in the gulag and then transcribed it from memory???

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

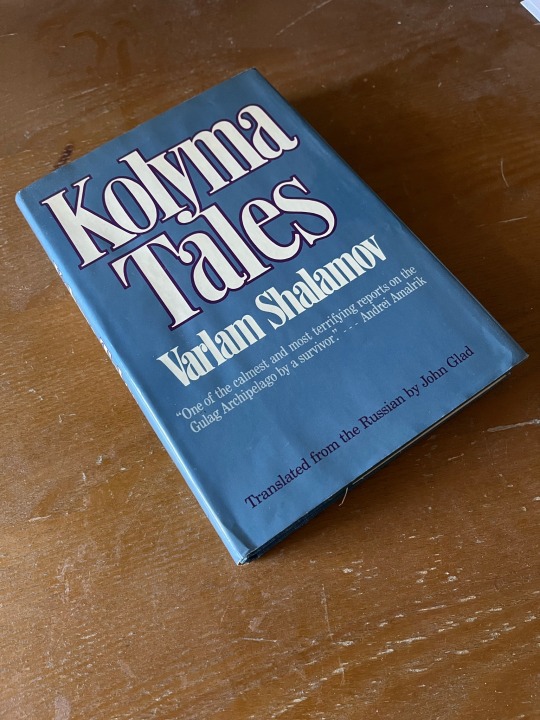

“The mountain had been laid bare and transformed into a gigantic stage for a camp mystery play.

A grave, a mass prisoner grave, a stone pit stuffed full with undecaying corpses of 1938 was sliding down the side of the hill, revealing the secret of Kolyma.

In Kolyma, bodies are not given over to earth, but to stone. Stone keeps secrets and reveals them. The permafrost keeps and reveals secrets. All of our loved ones who died in Kolyma, all those who were shot, beaten to death, sucked dry by starvation, can still be recognized even after tens of years. There were no gas furnaces in Kolyma. The corpses wait in stone, in the permafrost.

In 1938 entire work gangs dug such graves, constantly drilling, exploding, deepening the enormous gray, hard, cold stone pits. Digging graves in 1938 was easy work; there was no "assignment," no "norm" calculated to kill a man with a fourteen-hour working day. It was easier to dig graves than to stand in rubber galoshes over bare feet in the icy waters where they mined gold - the "basic unit of production," the "first of all metals."

These graves, enormous stone pits, were filled to the brim with corpses. The bodies had not decayed; they were just bare skeletons over which stretched dirty, scratched skin bitten all over by lice.

The north resisted with all its strength this work of man, not accepting the corpses into its bowels. Defeated, humbled, retreating, stone promised to forget nothing, to wait and preserve its secret. The severe winters, the hot summers, the winds, the six years of rain had not wrenched the dead men from the stone. The earth opened, baring its subterranean storerooms, for they contained not only gold and lead, tungsten and uranium, but also undecaying human bodies.

These human bodies slid down the slope, perhaps attempting to arise. From a distance, from the other side of the creek, I had previously seen these moving objects that caught up against branches and stones; I had seen them through the few trees still left standing and I thought that they were logs that had not yet been hauled away.

Now the mountain was laid bare, and its secret was revealed. The grave "opened," and the dead men slid down the stony slope. Near the tractor road an enormous new common grave was dug. Who had dug it? No one was taken from the barracks for this work. It was enormous, and I and my companions knew that if we were to freeze and die, place would be found for us in this new grave, this housewarming for dead men.

The bulldozer scraped up the frozen bodies, thousands of bodies of thousands of skeleton-like corpses. Nothing had decayed: the twisted fingers, the pus-filled toes which were reduced to mere stumps after frostbite, the dry skin scratched bloody and eyes burning with a hungry gleam.

With my exhausted, tormented mind I tried to understand: How did there come to be such an enormous grave in this area? I am an old resident of Kolyma, and there hadn't been any gold mine here as far as I knew. But then I realized that I knew only a fragment of that world surrounded by a barbed-wire zone and guard towers that reminded one of the pages of tent-like Moscow architecture. Moscow's taller buildings are guard towers keeping watch over the city's prisoners. That's what those buildings look like. And what served as models for Moscow architecture - the watchful towers of the Moscow Kremlin or the guard towers of the camps? The guard towers of the camp "zone" represent the main concept advanced by their time and brilliantly expressed in the symbolism of architecture.

I realized that I knew only a small bit of that world, a pitifully small part, that twenty kilometers away there might be a shack for geological explorers looking for uranium or a gold mine with thirty thousand prisoners. Much can be hidden in the folds of the mountain.

And then I remembered the greedy blaze of the fireweed, the furious blossoming of the taiga in summer when it tried to hide in the grass and foliage any deed of man - good or bad. And if I forget, the grass will forget. But the permafrost and stone will not forget.” (p. 178 - 180)

#shalamov#varlam shalamov#kolyma tales#kolyma#gulag#stalin#communism#soviet union#soviet literature#russia#russian lit#aleksandr solzhenitsyn#death#moscow

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

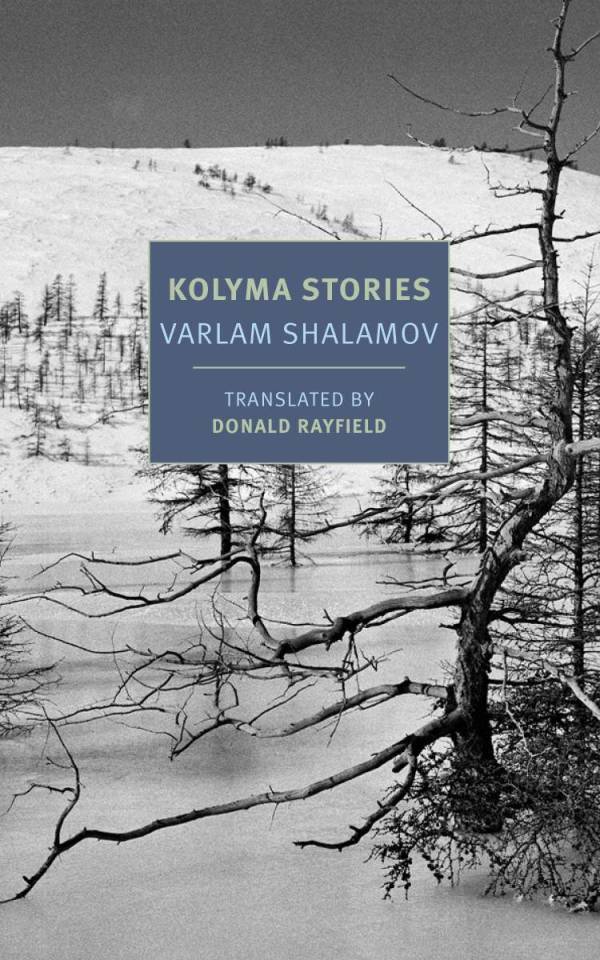

KOLYMA STORIES - Varlam Shalamov (1954-1965, transl. 2018) & TELLURIA - Vladimir Sorokin (2013, transl. 2022)

Two very different books this time, both translated from Russian, both published by New York Review Books, and both collections of short stories of sorts.

Telluria is a work of speculative fiction, set in a future Russia.

Kolyma Stories is not so fictional, as it is Shalamov’s personal account of his 15 years in the gulag – one of the very few that survived in the system for such a long time. I’m…

View On WordPress

#1970s#2010s#Donald Rayfield#Варла́м Шала́мов#Влади́мир Соро́кин#Колымские рассказы#Теллурия#gulag#Kolyma Stories#Kolyma Tales#Literature#Max Lawton#Russia#Russian literature#Science Fiction#Telluria#Varlam Shalamov#Vladimir Sorokin

1 note

·

View note

Text

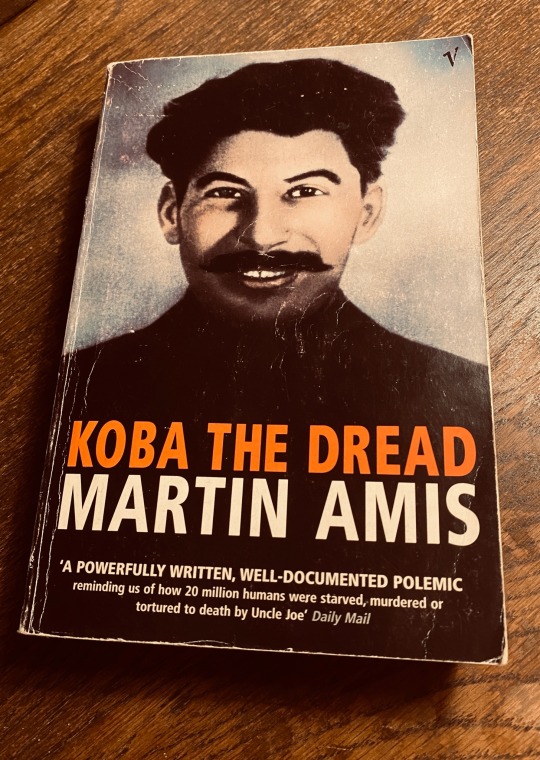

#martin amis#koba the dread#stalinism#Leninism#marxist leninist#trotsky#aleksandr solzhenitsyn#gulag#the gulag archipelago#bolshevism#literature#history#poetry#poem and poetry#my books#personal notes#n.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Historically, some of the biggest Russian opponents to domestic repressions are imperialists. Solzhenitsyn, most famously, is, on the one hand, bravely fighting the GULAG, and on the other hand - a vile imperialist with a sense of fascism. These aren't new phenomena, in many ways. Somehow one feels that [moving away from imperialism] is unlikely in Russia, because it goes so deep. This is just the latest Russian invasion of Ukraine, this is not just one war, this has been going on for centuries. Russian imperialism is embedded in Russian humour, Russian literature, codes of thinking. It's not about statements. It's not just about policies. When Pushkin writes, I don't know, "Кавказ подо мною" ("The Caucasus lies below me"), one of his famous poems... the amount of imperialist psychology that goes into saying that - that goes very, very deep. So until those much, much deeper sort of deep cultural roots of Russian imperialism, racism and oppression are addressed, nothing is changed. So let's think what we have agency over, in a way. [...] we can change the way Russia is perceived globally and in the West. Because this idea that Russia is a great power that has the right to a sphere of influence and that has the right to suppress others because it's great - that sits very deep in people's heads across the world. We can start working on that. So why don't we start working on that? Let's get people in my world - Britain, America - to re-read the Russian classics and understand how much imperialism and oppression of others there's there. Let's start de-mystifying this idea of "the Russian mystic soul" and really start rooting it to very specific histories of violence and oppression. Let's start changing the way Russia is perceived, so it's no longer seen as inevitable and so vast and huge that you have to drop on your knees in front of it, which still sits in people's heads. That means changing the way the universities overfocus on Russia studies and completely silence the voices of Ukrainians, Georgians, Kazakhs... There's so much we can do that will make people's perceptions of Russia rooted in reality. And they will help gain self-confidence to say, "Stop, we're not dependent on you".

Peter Pomerantsev

#peter pomerantsev#russian imperialism#russian culture#ruscism#russian invasion of ukraine#russian colonialism

399 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Ukrainians didn’t produce a Tolstoy?

there are a lot of things that can piss me off, today it was this tweet:

and all i wanted to do was to ask this person, why the fuck do we need a racist misogynistic piece of shit as a standout author if we have Shevchenko as our prophet?

but you don’t know who he is? of course, you don’t. that is the thing with imperialism: you destroy other cultures while promoting yours as the only way to legitimise your rule. even if those territories are of higher cultural development. but there is always a way out of it: kill them all. kill anyone who poses an existential threat to your hegemony. throw them into jail. forbid them to write and paint. send them to gulag. kill them. torture them. execute them.

if you don’t know Ukrainian literature, it doesn’t mean that it‘s nonexistent. if you don’t know "a Ukrainian Tolstoy", it means there is a Ukrainian Bahrianyi, who was sent to the gulag but ran away and was the first person in the world to openly criticise USSR in his pamphlet Why I am not going back to the Soviet Union. "I don't want to go back to the USSR because a person there is worth less than an insect"

there is a Ukrainian Symonenko and a Ukrainian Stus. there is a Ukrainian Lesya Ukrainka and Olha Kobylyanska. a Ukrainian Kotsiubynskyi, Ukrainian Drach, Ukrainian Olena Pchilka and Ukrainian Lina Kostenko. and so many more of the bravest people who despite all wrote in the Ukrainian language about Ukrainian people and for Ukrainian people.

there are thousands of beautiful texts that weren’t translated because this would’ve harmed the empire. that is why you are reading Dostoevsky and not Khvyliovyi.

but there are also thousands of texts that were never written. just how many more poems would’ve Stus written if he wasn’t killed by the Soviet regime? how many more texts would have Pidmohylnyi, Semenko, Yalovyi, Yohansen, Zerov written if they weren’t shot at Sandarmokh?

just how many texts have the world missed out on because Khvyliovyi committed suicide as he couldn’t live in the world with Stalin’s repressions. "today is a beautiful sunny day. I love life - you can't even imagine how much", - he will write in his death note as he shot himself with his friends waiting for him in the next room.

or maybe there was a Ukrainian Nobel Prize in Literature waiting for Tychyna? maybe, but he submitted to Soviet authorities and started writing hails for the regime, suddenly forgetting his own literary style and living his entire life in fear. fear of what? fear of getting caught. of getting destroyed just as all of the previous Ukrainian intelligentsia.

I’m tired of my people being silenced. I’m tired of my poets being undermined by "great” russian literature. it’s not worth a single Symonenko’s poem. it’s not worth a single paragraph of Bahrianyi‘s prose.

the greatness of russian literature lies on the bones of Ukrainian writers. to be this high, they killed hundreds and they are still doing it today.

the body of Ukrainian children’s writer Volodymyr Vakulenko was found in the mass grave in Izium in September 2022.

there will be a Ukrainian Nobel Prize in Literature, and there will be more Ukrainian books. there will be Ukrainian Zhadan and Zabuzhko, Liubka and Izdryk, Deresh and Kidruk. there will be Ukrainian literature.

another funny thing is that this person is Indian and let me tell you: the fact that you stand up for one empire even when your own country has suffered from the doings of another is evidence of deep colonial trauma and I hope you will cure yourself soon

576 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh Heavy. How are you somehow everywhere yet underrated at the same time???

Genuinely don't see a lot of people talk about Heavy. Heavy mains are so few and far in between that im half convinced theyre endangered species. But enough about the game, I'm talking about the fandom. In terms of his canonical personality theres not a lot of people Ive seen hyping him up. The most ive seen is him being a boytoy to Medic, like come on this man deserves a lot better than just being referred as Medic's boyfriend. I have nothing against the ship, but lets talk about Heavy more than once in a while, pls.

See, this man has gone thru a whole lot. He was put through the gulags as a young man because of his father being against the communist party, escaping during a fire. Him and his family have been hiding in the mountains ever since. Hes so quiet and reflective. Hes more than a big guy with big guns, he is very observant and clever. I love his hyperfixations on guns and names them haha thats really sweet. He does not have very good english, but he is very educated having a phD in Russian Literature.

Honestly I dont even know why the fandom dont talk about him. The fanfic prompts are right THERE!!! COME ON

#tf2#team fortress 2#tf2 heavy#tf2 milkhail#god this man deserves better#his backstory is really sad and the fact he doesnt wanna talk about it really makes me feel so bad#i wanna make an essay on why hes wonderful and deserves your attention

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Armenian fiction books that I wish had English translations so more foreigners could read them.

1. The Killed Dove by Nar-Dos.

The action takes place in the 1890s in Tiflis (Georgia). The story is written from Mikael's point of view. At midnight, his friend Garegin visits him with the news that he's getting married to a woman named Sara and that he'll be the groomsman. After meeting Sara, he quickly finds out that she is not enthusiastic about being married as her fiance, in fact she acts quite distant from him. After some time, when he has heard nothing from Garegin, another friend of his, Ruben, who dropped out of university and is now writing a book, "The Killed Dove", in which he tells how he went hunting with a girl. During the hunt he kills a dove and the girl starts crying and comparing herself to it. I don't want to give away all the plot points (hopefully you'll read it one day), but the stories of all the characters mentioned are connected. Some time later, Garegin appears and tells Mikael that Sara is obsessed with "revenge".

But what I like about this book is not just the plot, but the way Sara is portrayed, despite being morally ambiguous, she is still tragic and easy to sympathise with. Also, the book actively acknowledges the misogyny in Armenian society.

2. Blooming Barbered Wire/ Barbered Wire in Bloom (not sure which translation is better) by Gurgen Mahari

A book of autobiographical nature that was actually banned in the USSR. G. Mahari is sentenced to 10 years in the gulag and exile. It doesn't have a plot like A to B, but you get to know the life of the prisoners, what they eat, how they try to escape but fail, the love story of a Jewish woman artist with a high education and an average Azeri man. Although the situation is not the happiest, there are still funny references and sarcasm.

3. Unwitting Travelers by Vardges Kalantaryan.

Bunch of boys and girls travelling through woods and have to stay in rocks (its children's literature). I remember it as very adventurous and funny. In the second part, the characters are young adults.

There are actually more but I'm alredy tired.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Team Fortress 2 Mercenary Ages - given all of the canon information we know!

Scout - 27

In the TF2 Comic “The Naked and the Dead,” Spy (Scout’s biological father) states that Scout was conceived 27 years ago, making Scout 27. This is the only 100% confirmed age.

Soldier - mid 40s to early 50s

It’s stated in Soldier’s description that he attempted to join the army during WWII. If we assume Soldier was a young adult when he attempted to enlist, he would now be in his mid 40s to early 50s during the events of TF2.

Pyro - unknown

There is very little information out there on Pyro. It would be impossible for me to accurately identify their age.

Demoman - mid 30s

The only information I have in regards to demoman’s age comes from a line his mother says in the book “Valve Presents Volume 1: The Sacrifice and Other Steam-Powered Stories” in which Demo’s mother remarks: “No demoman worth his Sulfur ever had an eye in his head past thirty!” Which means Demo is most likely somewhere in his 30s.

Heavy - mid 40s to early 50s

In the update comic “Meet the Director,” it is revealed that Heavy was sent to a North Siberian Gulag in September 1941 alongside his mother and sisters. Heavy also canonically has a PhD in Russian literature, as revealed through his dialogue in the game ‘Poker Night at the Inventory.’ It would take around 9 years to obtain that PhD, meaning- depending on if he obtained the degree before or after 1941, he would be either in his mid 40s or early 50s.

Engineer - early to mid 30s

Engineer designed and built the Sentry under contract from TF industries in 1965, with him also spending 10 years in the West Texas oil fields- assuming Engineer was 18 before this date, he would be in his early to mid 30s during the events of TF2.

Medic - late 30s to early 40s

Medic’s description explicitly states that he was “Raised in Stuttgart, Germany during an era when the Hippocratic oath had been downgraded to an optional Hippocratic suggestion,” This implies that Medic was brought up during, or just before, WWII. The word ‘raised’ heavily implies the Medic to still be in adolescence during this era, making him surprisingly younger than expected, with him being around his late 30s to very early 40s during Team Fortress 2.

Sniper - early 30s

In the Team Fortress 2 comic ‘Blood in the Water’, Miss Pauling directly states that New Zealand sunk 40 years ago- in the same comic, Sniper is shown as a baby in a flashback, 10 years after New Zealand sunk. This makes Sniper out to be 30 or 31 in the TF2 present.

Spy - unknown, estimated early-mid 50s

Given Spy’s secretive nature, it’s difficult to deduct how old he is. However, since he has a 27 year old son, it’s likely that he is in his mid 50s. There is a single comic panel (Found in ‘Unhappy Returns’) depicting Spy’s hair to have a grey tint to it, further emphasising this fact.

#feel free to let me know of any mistakes ive made/anything ive missed#there’s a lot of debate about the merc’s ages#especially given all the retconns and contradictory evidence within tf2#so i tried my hardest to stick solely to 100% canon tf2 material instead of common headcanon and popular fanmade materal#i didnt include any community info (i.e the track terroriser) as im trying to only reference completely canon material#ok Cool hope u all enjoy#tf2#team fortress 2#team fortress two#medic tf2#scout tf2#sniper tf2#pyro tf2#demoman tf2#heavy tf2#spy tf2#engineer tf2#soldier tf2

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The idea of mothering and procreation morphed into Gorky’s fascination with prisoner transformation and perekovka. The labor camp would be the mother of a new working class. Both god-building and the maternal impulse dovetailed with the author’s largest philosophical and intellectual preoccupation: human fashioning. Whether it was the literal, biological creation of the human by the maternal womb or the transformation afforded by a personal journey or individual greatness, Gorky remained intrigued by the individual’s ability for creation, journey, and self-discovery. Maintaining that humans were inherently malleable and eternally improvable, he believed in the potential for endless refinement through diligent effort.

Gorky’s special relationship to the Belomor project allows for an understanding of his career as a symbolic representation of the ideals promoted at the camp. Gorky was a staunch enthusiast of prisoner labor and even predicted the possibility of a waterway similar to Belomor in his early works; in the April 1917 issue of his journal New Life (Novaia zhizn’) he writes

Imagine, for example, that in the interest of the development of industry, we build the Riga-Kherson canal to connect the Baltic Sea with the Black Sea […] and so instead of sending a million people to their deaths, we send a part of them to work on what is necessary for the country and its people.

Gorky’s condoning of Gulag camps such as Solovki and Belomor seems paradoxical to many scholars in light of his humanitarian endeavors, and some speculate either that Gorky was ignorant of the full extent of Stalin’s butchery or that he was aware, but was in a position that necessitated acquiescence to safeguard his well-being. When viewed in the context of his philosophical outlook on literature and labor, however, his support of prison camps seems not like an aberration but rather a natural extension of his belief in violent re-birth, a belief related to Marxist-Leninist ideology and the concept of god-building. Gorky sees people and language alike in the framework of craftsmanship. Perhaps his mistake was not so much his general support of Gulag projects, but his belief that human flesh can be formed like words on a page or cement in a factory. Gorky, after all, cared more about the craft than people themselves; in his 1928 essay “On How I Learned to Write” (O tom, kak ia uchilsia pisat’), he claimed that “the history of human labor and creation is far more interesting and meaningful than the history of mankind.” Gorky was key to the canal project because his philosophical interests exemplify the very core of Belomor: the violent transformation of people through creative acts.

Technology’s magic demonstrated humans’ usurpation of God in a tangible way, with the ever-widening capacity to harness and transform the natural environment showcasing the potential of man-made machines. Soviet pilots were imagined as literal incarnations of the New Man, and the massive expansion of the Soviet aviation industry in the mid 1920s provided some of the most concrete evidence of human superiority over the divine. Short voyages known as “air baptisms” (vozdushnye kreshcheniia) supposedly eradicated peasants’ belief in God while highlighting the majesty of Red aviation. In such “agit-flights,” pilots would take Orthodox believers into the skies and show them that they held no celestial beings. Those who participated in the flights would narrate their experiences to neighboring villagers, describing “what lies beyond the darkened clouds.” This phrase served as the title of a 1925 essay by Viktor Shklovskii in which a village elder embarks upon a conversional agit-flight that he later recounts to his fellow peasants. Six years later, Shklovskii participated in the writers’ collective that coauthored the now infamous monograph History of the Construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal, in which a different, often deadly, type of technological program offered the promise of conversion. In both instances, darkness will be overcome by the enlightening potential of socialist rationalism: aviation will liberate the peasants from their ignorant beliefs, just as labor will supposedly bring the Belomor prisoners to the light of Soviet ideology. Such endeavors occurred before the backdrop of a larger civilizing project, since both the rural reaches of peasant villages and the wild expanses of untouched Karelia necessitated modernization.

Yet could such projects ever be completed? Did the New Man really exist, and could his creation ever be achieved? The messianic vision of Soviet socialism necessitated that paradise lie always just out of reach.

Similarly, Nietzsche posits the development into the Übermensch as a perennially elusive goal; like the Faustian concept of striving, the individual is forever trying to perfect oneself without necessarily ever achieving perfection. This constant yearning renders the present as the future, as the purpose of today is necessarily the reward of tomorrow. In the Soviet Union, the regime assured people that the difficulties they endured were required in order to reach the svetloe budushchee (radiant future), a utopia found at the end of an interminable road. In the absence of an end result or final destination, the voyage itself becomes the site of cultural exploration."

- Julie Draskoczy, Belomor: Criminality and Creativity in Stalin’s Gulag. Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2014. p 30-32

#maxim gorky#new man#belomorkanal#belomor#gulag#white sea baltic canal#Беломо́рско-Балти́йский кана́л#prison camp#work camp#soviet history#soviet union#stalinism#academic quote#reading 2024#history of crime and punishment#perekovka#russian revolution#soviet communism

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sources & Further Reading

This list is continually updated. I try to stick to studies or articles that are available for free, but bear with me if i link to something behind a paywall. For books, I link to Goodreads, where you'll find blurbs, reviews, and purchasing options.

Torture:

freedomfromtorture.org

The Ethics of Torture: Definitions, History and Institutions (2012), Evans

When and Why We Torture: A Review of Psychological Research (2017), Houck, Repke

The Torture Myth, Anne Appelbaum

The Effects and Effectiveness of Using Torture as an Interrogation Device: Using Research to Inform the Policy Debate (2009), Costanzo, Gerrity

Psychological Effects of Torture (2010), Jayatunge

Torture and its Consequences: Current Treatment Approaches, Metin Basoglu

Political Torture in Popular Culture: The Role of Representations in the Post 9/11 Torture Debate (2016), Adams

How to Justify Torture: Inside the Ticking Bomb Scenario, Alex Adams

Why Torture Doesn't Work: The Neuroscience of Interrogation, Shane O'Mara

Torture and Democracy, Darius Rejali

Gestures of Testimony: Torture, Trauma and Affect in Literature, Michael Richardson

The Cognitive Dissonance Theory of Torture Perceptions (2015), Houck

Trauma:

What is Moral Injury?

Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services, SAMHSA

Of Monsters and Men: Perpetrator Trauma and Mass Atrocity (2015), Mohamed

Exploring Perpetrator Trauma Among a Cohort of Violent Juvenile Offenders (2023), Mahlako

Psychology:

Everyday Sadism, Dark Triad, Personality and Disgust Sensitivity (2017), Meere & Egan

Sadism and Aggressive Behavior: Inflicting Pain to Feel Pleasure (2018), Chester, DeWall & Ejanian

The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness, R. D. Laing

Philosophy:

Act and Rule Utilitarianism, IEP

The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus

The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli

The Art of War, Sun Tzu

History & Biography

Man's Search for Meaning, Viktor E. Frankl

Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption, Laura Hillenband

The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

The Torture Machine: Racism and Police Violence in Chicago, Flint Taylor

Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, Christopher R. Browning

The ISIS Hostage: One Man's True Story of 13 Months in Captivity, Puk Damsgård

#sources#resources#torture#psychology#philosophy#history#nonfiction#havent read all of these yet so its also kind of a to-read list tbh

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

I last saw my old professor Abduqadir Jalalidin at his Urumqi apartment in late 2016. Over home-pulled laghman noodles and a couple of bottles of Chinese liquor, we talked and laughed about everything from Uighur literature to American politics. Several years earlier, when I had defended my master’s thesis on Uighur poetry, Jalalidin, himself a famous poet, had sat across from me and asked hard questions. Now we were just friends.

It was a memorable evening, one I’ve thought about many times since learning in early 2018 that Jalalidin had been sent, along with more than a million other Uighurs, to China’s internment camps.

As with my other friends and colleagues who have disappeared into this vast, secretive gulag, months stretched into years with no word from Jalalidin. And then, late this summer, the silence broke. Even in the camps, I learned, my old professor had continued writing poetry. Other inmates had committed his new poems to memory and had managed to transmit one of them beyond the camp gates.

In this forgotten place I have no lover’s touch

Each night brings darker dreams, I have no amulet

My life is all I ask, I have no other thirst

These silent thoughts torment, I have no way to hope

Who I once was, what I’ve become, I cannot know

Who could I tell my heart’s desires, I cannot say

My love, the temper of the fates I cannot guess

I long to go to you, I have no strength to move

Through cracks and crevices I’ve watched the seasons change

For news of you I’ve looked in vain to buds and flowers

To the marrow of my bones I’ve ached to be with you

What road led here, why do I have no road back home

Jalalidin’s poem is powerful testimony to a continuing catastrophe in China’s Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Since 2017, the Chinese state has swept a growing proportion of its Uighur population, along with other Muslim minorities, into an expanding system of camps, prisons and forced labor facilities. A mass sterilization campaign has targeted Uighur women, and the discovery of a multi-ton shipment of human hair from the region, most likely originating from the camps, evokes humanity’s darkest hours.

But my professor’s poem is also testimony to Uighurs’ unique use of poetry as a means of communal survival. Against overwhelming state violence, one might imagine that poetry would offer little recourse. Yet for many Uighurs — including those who risked sharing Jalalidin’s poem — poetry has a power and importance inconceivable in the American context.

#current events#poetry#politics#chinese politics#oppression#censorship#resistance#imprisonment#uyghur genocide#china#xinjiang#uyghurs#abduqadir jalalidin

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

our ukrainian literature teacher is telling us about the executed renaissance (розстріляне відродження) and my blood runs cold as I'm listening to all these terrible things soviet union did to ukrainian artists. they literally slaughtered all of teh ukrainian artists who wouldn't create propagandistic artworks. sent them to gulags, psychologically (and probably not only psychologically) tortured them there. it's so fucking horrible I just can't put it into words. and all those westerns who glorify soviet union can go to hell. my people suffered for centuries AND YOU ROMANTICISE THE OPPRESSOR WITHOUT EVEN KNOWING A HALF OF THE HORRIBLE THINGS THEY DID

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A friend said she read Crime & Punishment but wasn't impressed by it. All she recalled was an entitled man killing an old woman and pity party for the murderer's poor tortured soul. This was my response to her, I thought others might enjoy it too.

"It is a staunch criticism, not a pity party. There was this idea of a cosmopolitan man, a Nietzschean übermensch was someone capable of transcending social and moral codes. Prime example being Napoleon, a man without parallel. Them being 'great' would make them invincible to guilt because all actions they took would be something considered beneficial to society - Raskolnikov thought he was one of these men, and by devolving throughout the narrative he realizes he is not one of these "great" men, he is just like any other citizen and there is no excuse for thinking morals and laws don't apply to you. It's a direct message to the students and academic men of the time. The old woman is a horrible loanshark and abuses the woman she lives with, her niece, and he tries to convince himself that killing her would be excusable since he considers her a cancer on society. But he also ends up killing the niece to cover up his crime as she returns and witnesses it - removing even that sliver of argument or defense for his actions.

He hoped to 'serve humanity' by eradicating the mean-spirited moneylender, but also had the utilitarian idea that he would steal her money and use said money to further his education, so that he could become a great man and have positive influence and help more people. The whole murder has the spirit of a psychological experiment which fits the theme and craft of the novel. Raskolnikov has delusions of godhood and this is after Dostovyevsky has been in a gulag for 10+ years, so he knows that the young think themselves immortal and anointed, a common misconception of the youth in western education at the time and even to this day,

After killing her he realizes just how much he is not beyond good and evil. Something he previously thought was petty, something for plebians.

It has three dimensions, his biography, his christian faith (there's several references to the bible and lazarus who he symbolizes) and criticism/exploration of philosophical ideas. Its a direct response to utopian socialism and rational nihilism. He even foresaw many of the horrors of the russian revolution.

The epilogue is not just redemption, but sanctification. Raskolnikov has become a saint. Russian religion at the time was very orthodox and process-oriented, so we follow the steps of his redemption in the narrative. He confessed his sin out of weakness instead of strength, his transformation from the snivelling arrogant youth to a saint is not verbal, its a lived out experience and process.

even the title in russian refers to the carrying of a cross, the very first scene is him crossing a bridge from the dirty streets of Skt. Petersburg to fresh clean air of the pastoral. Both foreshadowing and commentary on the squalor most of the citizens live in. as well as the moral degradation of the cosmopolitan cities. Skt. Petersburg was usually described as extravagant and beautiful in literature, while he describes it as smelly, dirty and sort of a wasteland - a hell, you might say.

There's also this dominating motif of christian authenticity that is typical of russian lit. A christian heart will react in a christian way - meaning it will recognize good and evil in a way that a rationally educated mind does not. (especially in reference to that horrible scene with the horse)

Raskolnikov is described as a misanthrope, and alienated from both religion and other people, leading him to commit same sin as Cain, not killing his brother per se, but a fellow human being. that very act transforms him. something in him dies with the moneylender - his common humanity.

out of that death comes a different life, drawing parallel to Lazarus as I mentioned before. It's like a whole hermeneutic event, his return to common humanity starts with Sonia telling him the very story of Lazarus.

anyway, enough of me writing novels about novels! It's so convoluted and deep and I genuinely love it. Its a prime example of literature being an educating, moralizing element capable of engendering empathy and inspiring positive social progress."

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lots of analysts on the right throw the term “communism” around recklessly.

Even I, on occasion, flippantly refer to this or that as “commie” because it’s a fun word, even when it doesn’t necessarily apply.

But this, boys and girls, is about as close to literal communism as we’ve ever seen in American politics, in that Marx envisioned a revolution in which the proletariat (working stiffs) rises up and throws off the shackles of the capitalist bourgeoisie (Jeff Bezos types) in an orgiastic liberatory celebration of humanity.

Via Investopedia (not the best source for economic philosophy, but a decent synopsis nonetheless) (emphasis added):

“Marx thought that the capitalist system contained the seeds of its own destruction. The alienation and exploitation of the proletariat that are fundamental to capitalist relations would inevitably drive the working class to rebel against the bourgeoisie and seize control of the means of production.

This revolution would be led by enlightened leaders, known as “the vanguard of the proletariat,” who understood the class structure of society and would unite the working class by raising awareness and class consciousness.

After the revolution, Marx predicted, private ownership of the means of production would be replaced by collective ownership, first under socialism and then under communism.

In the final stage of human development, social classes and class struggle would no longer exist.”

The problem here is one of turning theory into practice. Marx never illuminated how this process to the final destination of stateless utopia might unfold, just that it should via abstract “consciousness.”

In practice, the mechanism by which the capitalist system is overthrown becomes the state, which, out of its self-interest, prevents the final revolution — the dissolution of the state — from ever manifesting.

Stuck in limbo.

Chaos ensues.

Central planning becomes the economic model.

People starve.

People die.

People write great literature about hell on Earth (see: Gulag Archipelago).

And it all starts seemingly innocently enough with state-run grocery stores.

4 notes

·

View notes