#gylan kain

Photo

(via Gylan Kain, a Founder of the Last Poets and a Progenitor of Rap, Dies at 81 - The New York Times)

Gylan Kain, a Harlem-born poet and performance artist who was a founder of the Last Poets, the spoken-word collective that laid a foundation for rap music starting in the late 1960s by delivering fiery poetic salvos about racism and oppression over pulsing drum beats, died on Feb. 7 in Lelystad, the Netherlands. He was 81.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Proopcast Brings the Noise

Beyoncé goes Country, Oscar Winner Louis Gossett Jr., Director Norman Jewison, Last Poet Gylan Kain, Remembering the genius Gil Scott-Heron, Optimism and Activism. Shalom and Salam.

Jennifer lays down the law.

https://gregproops.com

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/the-smartest-man-in-the-world/id401055309

https://open.spotify.com/show/5GEa8PiRcBZjVjkQR5VO1L

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

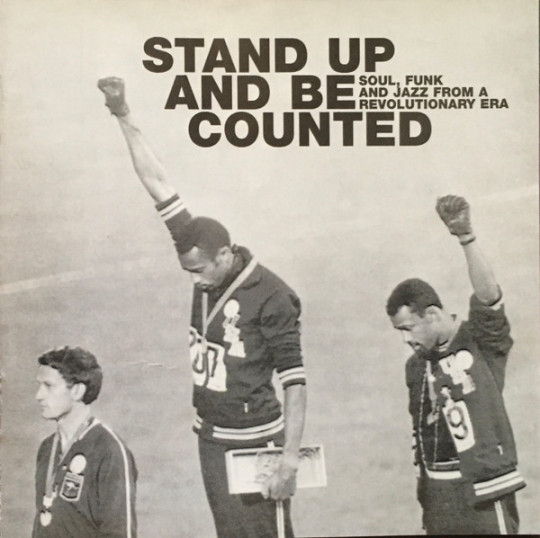

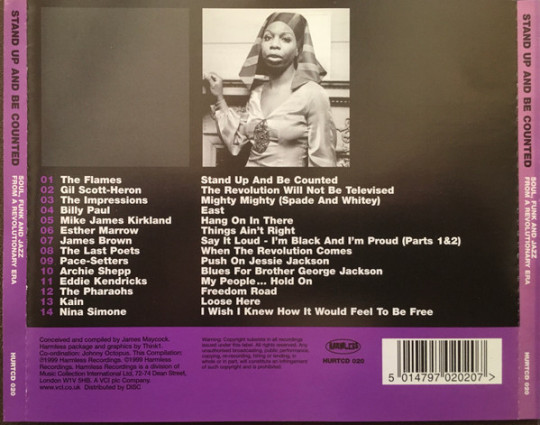

Today’s compilation:

Stand Up and Be Counted: Soul, Funk and Jazz from a Revolutionary Era

1999

Funk / Soul / Spoken-Word Poetry / Jazz

Today's an important history lesson, folks. I went back to a late 60s/early 70s era of US black revolutionary politics and awareness with this CD that was put out by UK label Harmless in '99. It's those pre-disco days when a lot of black-made music was politically righteous, with scathing lyrical critiques of a still racially unequal status quo, and carried poignant, urgent, and inspirational messages that would help to raise the consciousness among black folks nationwide, as well as anyone else who was willing to listen and learn. It was a time of riotous and fiery tumult, and while this release doesn't seem to fully encapsulate or present all the most prominent songs and musicians that ended up providing the soundtrack for this very volatile handful of pivotal years—where's Sly Stone?—it's still a phenomenal album.

This CD comes with fixtures you'd expect on a release like this: James Brown's "Say It Loud - I'm Black and I'm Proud," Nina Simone's "I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free," and perhaps the most iconic piece of spoken-word poetry that's ever been recorded, Gil Scott-Heron's "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised." Basically, if you're putting together an album that's trying to reflect the American black struggle from this specific time period, it'd be prudent to include this particular trio of songs.

But where this album truly shines is with its overwhelming majority of selections that aren't so obvious; songs that contain the same hunger and zeal for equality, but aren't as well known to a general audience. For example, The Last Poets, a spoken-word poetry trio whose early 70s pining for immediate revolution on their self-titled debut album would lay the foundation for the creation, development, and emergence of hip hop music and culture. Their song, "When the Revolution Comes," actually sparked a response from Gil Scott-Heron with "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised," and 22 years after its initial release, a repeated line towards the end of the song would find itself repurposed as the title of The Notorious B.I.G.'s debut single, "Party and Bullshit."

And also on here is a solo track from one of those Last Poets as well, Gylan Kain, whose 1970 song, "Loose Here," off of his debut LP, The Blue Guerrilla, was actually co-written by none other than the legend Nile Rodgers himself, earning him one of his first ever credits, long before he'd *really* break out with a pair of #1s on the disco tip in '78 and '79, with Chic's "Le Freak" and then "Good Times."

Truth be told, though, The Last Poets weren't actually as obscure as you may think that I might be making them out to be here; their debut album managed to sell over 350,000 copies, and it peaked at #29 on Billboard's 200 album chart, and #3 on R&B as well. It's just that, knowing about them was spread pretty much purely through word of mouth; there was certainly no big commercial engine that was driving their sales, and if you weren't black and didn't have your ears tuned to any of this sound, the likelihood that you'd catch wind of them was pretty low.

So, the most obscure song on this album, then, appears to be a funk tune from an anonymous group called The Pace-Setters, whose only ever release, a 1971 7-inch, sings the praises of social activist Jesse Jackson and his then-recently formed PUSH organization on its chugging a-side.

The rest of this CD's tunes are pretty much made up of brilliant funk, soul, and jazz entities—The Impressions, Billy Paul, Archie Shepp, and ex-Temptation Eddie Kendricks—but the album doesn't use any of their singles. All the choices are still terrific, however, especially Kendricks' "My People... Hold On," the slow, earthy, heartfelt, and mantric title track off of his 1972 sophomore album. Interestingly, the name of that album, though, actually chops off the "My" in "My People," suggesting that Motown imprint Tamla didn't want to potentially alienate any parts of its audience with such a transparent appeal to black pride and solidarity 🤔.

Another well-known group on this album is James Brown's former one, The Famous Flames, who are just credited as The Flames here. And as The Flames, they never released an album, but did put out a handful of singles, including this CD's title track, which lives up to the name of the group who made it (it's scorching!), and was produced by James Brown and released on his own label, People, in 1971.

And before I close out, I gotta mention Chicago jazz ensemble The Pharaohs too, because the penultimate track from their 1971 debut album, The Awakening, makes for a tremendous song, with astonishing traded leads between saxophone and guitar, and a constantly thick amount of busy backing behind it all as well. It would still be an amazing tune, even if it didn't have any kind of messaging to go along with it.

So, in sum, Stand Up and Be Counted is an incredible release. It really channels a very important few years of palpably churning American black fervor, and it includes some unforgettable all-timers too, but its real uniqueness is found in its many selections of non-singles, deep cuts, & relative obscurities. I really don't think you'll ever find another late 60s/early 70s black empowerment retrospective that's quite like this one here. A stunningly superb and authentic collection of tunes.

Highlights:

The Flames - "Stand Up and Be Counted"

Gil Scott-Heron - "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised"

The Impressions - "Mighty Mighty (Spade and Whitey)"

Billy Paul - "East"

Mike James Kirkland - "Hang On in There"

James Brown - "Say It Loud, I'm Black and I'm Proud, Parts 1 & 2"

The Last Poets - "When the Revolution Comes"

Pace-Setters - "Push on Jessie Jackson"

Archie Shepp - "Blues for Brother George Jackson"

Eddie Kendricks - "My People... Hold On"

The Pharaohs - "Freedom Road"

Kain - "Loose Here"

Nina Simone - "I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free"

#funk#soul#soul music#spoken word#poetry#poems#jazz#music#60s#60s music#60's#60's music#70s#70s music#70's#70's music

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Last Poets, a group of musicians and poet performers, originated out of the civil rights movement, with an emphasis on the Black re-awakening. The original Last Poets was founded on Malcolm X’s birthday, May 19, 1968, at the former Mount Morris Park in East Harlem. The original members, Felipe Luciano, Gylan Kain, and David Nelson took the name from a poem by South African poet Keorapetse Kgositsile, who believed that he was in the last era of poetry before guns would take over. They brought together music and spoken word.

The Original Last Poets would soon be overshadowed however by a group of the same name that spawned from a 1969 Harlem writer’s workshop called “East Wind.” Jalal Mansur Nuriddin, Umar Bin Hassan, Abiodun Oyewole, and percussionist Nilaja are considered the core members of this group. In 1970 this group appeared on their self-titled album. The Original Last Poets garnered some attention for their soundtrack to the 1971 film “Right On!” Following their debut album which made the top-ten lists, The Last Poets released The Last Poets (1970) and This is Madness (1971). Due to their politically charged lyrics, both groups were targeted by COINTELPRO.

Though the popularity of both groups declined by the late 1970s, the respect the rappers and lyricists of the post-1980s era have paid them has helped cement The Last Poets’ place in history as a major influence on the hip-hop and spoken word movements. The Last Poets influenced jazz and hip-hop artists ranging from Pharaoh Sanders and Senegalese drummer Aiyb Dieng to Public Enemy. Members of the two groups have attempted to bring them together. The Last Poets have collaborated with contemporary artists such as Common and Wu-Tang Clan. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

0 notes

Link

[ad_1] Gylan Kain, a Harlem-born poet and performance artist who was a founder of the Last Poets, the spoken-word collective that laid a foundation for rap music starting in the late 1960s by delivering fiery poetic salvos about racism and oppression over pulsing drum beats, died on Feb. 7 in Lelystad, the Netherlands. He was 81.He died in a nursing home from complications of heart disease, his son Rufus Kain said. His death was not widely reported at the time.The Last Poets, which originally consisted of Mr. Kain, David Nelson and Abiodun Oyewole, were aligned with the Black Arts Movement — the cultural corollary to the broader Black Power movement of the 1960s and ’70s — of which the activist poet and playwright Amiri Baraka was a central figure.With their staccato wordplay and sinewy rhythms, the Last Poets were pioneers of performance poetry, spinning out portraits of Black street life that often bristled with the guerrilla spirit of revolution.They made their public debut on May 19, 1968, in Mount Morris Park, now Marcus Garvey Park, in Harlem, at a celebration of the slain civil rights leader Malcolm X. Less than two months after the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, it was a fraught period in Black America, but also a time percolating with calls for dramatic change.“There was such electricity in the air,” Mr. Kain said in “The Last Poets,” a 2002 documentary that includes commentary by Isaac Hayes, Ossie Davis and KRS-One. “There was so much happening in the world of Black consciousness. It was just a good time for Black people to be alive — and young Black people in particular.”The Last Poets were often deeply confrontational, aiming to shake apolitical Black listeners into action with the most racially charged language possible. Still, Mr. Kain considered himself a poet and not a proselytizer, as evidenced by his lyricism on “James Brown,” one of 18 performances included in the 1970 film “Right On!”:Cry the painOf broken menThat stumble past empty dreamsWhen night opens wide its mouthTo grind you, swallow youInto pieces of black dustAnother number featured in that film, “The Shalimar,” used rich and rhythmic language to conjure the scene at a Harlem bar: “The voodoo, hoodoo, what-you-don’t-dare-do people/Move out from the walls, bust up from the floors.”Two decades later, a snippet from Mr. Kain’s introduction to the track — “like we always do about this time” — wove its way into hip-hop lore, appearing as a sample on Dr. Dre’s landmark 1992 album, “The Chronic,” as well as on “Doggystyle,” Snoop Dogg’s debut album, in 1993.The Last Poets came to be celebrated as rap progenitors, along with their contemporary Gil Scott-Heron, probably best known for his 1970 tour de force “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” who is often called the godfather of rap.In a 2010 profile of Mr. Scott-Heron in The New Yorker, Chuck D of Public Enemy was quoted as saying that the Last Poets and Mr. Scott-Heron were “not only important; they’re necessary, because they are the roots of rap — taking a word and juxtaposing it into some sort of music.”“You can go into Ginsberg and the Beat poets and Dylan,” he added, “but Gil Scott-Heron is the manifestation of the modern word. He and the Last Poets set the stage for everyone else.”Frank Gillen Oates was born on May 26, 1942, in Harlem. He was raised by his mother, Hilda Oates, and spent much of his childhood the South Bronx. As a youth, he attended services in Pentecostal churches, where the thundering oratory showed him at a young age the power that words had to sway hearts and minds.The family eventually moved to Queens, where he developed a love of theater — Shakespeare in particular — at Long Island City High School. After a stint at Hunter College in Manhattan, he began acting and adopted a new name, a twist on Dylan, in reference to the poet Dylan Thomas, and the biblical figure Cain, whom Albert Camus described as the original rebel.In 1965, Mr. Kain founded the Far East Theater in the East Village, which featured plays, readings and political symposiums. Before long, he saw a new way to reach Black audiences, drawing inspiration from the Beats, who often performed free verse with a jazz accompaniment.“I had said to my fellow Black artists down there in the Village, ‘I’m going to go up to Harlem and do poetry for Black people,’” Mr. Kain recalled in the 2002 documentary. “And these fellow Black artists who — at that time, it’s all new, it doesn’t exist yet — they said, ‘Black people don’t like poetry.’“So I said, ‘They’ll like mine.’”The Last Poets developed an ardent following. They performed on “Soul!” a television variety show showcasing Black musicians and other artists; at the East Wind, a cultural center on 125th Street that served as their headquarters; and on tours of colleges around the country.But tensions would soon arise. Mr. Kain chafed at an offer to record an album for a white producer’s label. “I said no because he was a businessman who had no interest in what we collectively were trying to make happen,” he said in the documentary. “The Black Power mandate was that we were going to build our own institutions.”The group’s lineup evolved, and within two years it had split into two factions fighting for the Last Poets name. Mr. Oyewole, along with Alafia Pudim, Umar Bin Hassan and the drummer Nilaja Obabi, released an album called “The Last Poets” in 1970, while Mr. Kain, Mr. Nelson and Felipe Luciano (the future community activist and television journalist) made it onto vinyl in 1971 as the Original Last Poets on the soundtrack album for “Right On!”By then, Mr. Kain had already left the group to focus on acting, although he did release a solo album, “The Blue Guerrilla,” which Thom Jurek of AllMusic described as “a freestyle set before such a thing was even a dream.”“Kain’s one pissed-off cat,” Mr. Jurek said, “raging not only against the usual necessary concerns, but also against the stereotypes in his own community.”Mr. Kain acted in productions at Joseph Papp’s Public Theater in New York, including “The Black Terror” in 1971, in which he had the lead role as a revolutionary assassin. In his New York Times review, Clive Barnes wrote that Mr. Kain gave “a beautifully understated and thoughtful performance,” adding, “His doubts and worries are always apparent, but so is his withdrawn strength and dignity.”By 1984, Mr. Kain had grown weary of life in the United States. After the murder of a close friend, he moved to Amsterdam, where he continued to act, perform his poetry and record, including a 1997 solo album, “Feel This.”Mr. Kain’s marriage to June Lum ended in divorce; they had three children. Along with his son Rufus, from his relationship with Lian Schaab, Mr. Kain’s survivors include two other sons, Khalil Kain and Khayyam Kain, from his marriage; two daughters, Khairah Klein (from his marriage) and Amber Kain (from his relationship with Karen Perry); and seven grandchildren.Despite their lasting legacy, the Last Poets had little sense of destiny in their earliest days.“Our first performances were for ourselves, and it went on for weeks and months,” Mr. Kain said in the documentary.“You play an instrument,” he added, “and you practice it, and nothing’s happening, but you know the scale, and one day, music comes out of it. And I’m saying, one day, music came out of this effort.” [ad_2] Source link

0 notes

Photo

Gylan Kain, 81, a Founding father of the Final Poets and a Progenitor of Rap, Dies

0 notes

Video

youtube

Lecture 20: Pioneers of the “spoken word,” The Last Poets were founded in 1968 by a group of New York City musicians and poets (originally consisting of Felipe Luciano, Gylan Kain, and David Nelson – although others would join the collective) sympathetic to the Black Power Movement. They were part of a larger cultural phenomenon known as the Black Arts Movement – a renaissance of African-American artistic expression that exploded in the second half of the 1960s and continued well into the 1970s. This song, “Panther,” is typical of their radical spoken word poetry of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

0 notes

Photo

Film still of The Last Poets during the filming of 'Right On!', [from left to right: David Nelson, Felipe Luciano, and Gylan Kain], New York, NY, ca. 1970 [Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. © Herbert Danska]

#art#still#film#photography#music#poetry#herbert danska#the last poets#david nelson#felipe luciano#gylan kain#national museum of african american history and culture#smithsonian institution#1970s

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Late Night Tip

WCSB Cleveland playlist from 12:30 to 1:00 am

Inez Foxx - Let me down easy

Mach Hommy - I wanna be more

Pete Rodriguez - Oh that’s nice

Les Toupas Du Zaire - Je Ne Bois

Gylan Kain - Look out for the blue guerilla

King Krule - Biscuit Town

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Lecture 20: Pioneers of the “spoken word,” The Last Poets were founded in 1968 by a group of New York City musicians and poets (originally consisting of Felipe Luciano, Gylan Kain, and David Nelson – although others would join the collective) sympathetic to the Black Power Movement. They were part of a larger cultural phenomenon known as the Black Arts Movement – a renaissance of African-American artistic expression that exploded in the second half of the 1960s and continued well into the 1970s. This song, “Panther,” is typical of their radical spoken word poetry of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Time ain't real nohow." Gylan Kain #ChangeYourExpectationsChangeYourLife https://www.instagram.com/p/CCvzuQBJfxM/?igshid=1txj6esry8x3a

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Remembering Jalal Mansur Nuriddin, the Grandfather of Rap, in 6 Songs

Jalal Mansur Nuriddin, a foundational member of the spoken-word crew the Last Poets, was a black revolutionary whose words helped spawn rap as we know it. Though not often mentioned among hip-hop’s founding fathers, Nuriddin had a great influence on groundbreaking rap acts like N.W.A., Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five, and A Tribe Called Quest. He died in his sleep Tuesday evening, at the age of 74.

The Last Poets were, in many ways, the first rappers. Nuriddin’s tag teams with Suliaman El-Hadi on 1972’s Chastisment ushered in a concept he referred to as “jazzoetry,” with fluid, rap-like inflections. And as Lightnin’ Rod, Nuriddin created what is often cited as the prototype for gangsta rap. His work was formative for Digable Planets, shaped the sound and vision of Main Source’s debut, Breaking Atoms, and was sampled by many others. He had a greater solo impact than any of his peers.

Seven men recorded as the Last Poets, but never at the same time. The first version of the group, founded by Gylan Kain, David Nelson, and Abiodun Oyewole in 1968, was born performing in a Malcolm X commemoration. Nuriddin co-led the second iteration of the group, which was also the most popular. He was one of the last two men to bear the Last Poets name, but the most dogged in his right to claim it; he recorded under the moniker more than any other member.

Nuriddin’s faction of the group released their self-titled debut in 1970. Their pro-black screeds, full of radical politics weaponized to dismantle the structure of white power, were ignored by local radio, but their buzz around the community was so intense that they were booked to play songs like “Niggers Are Scared of Revolution” at the Apollo alongside R&B crooners the O’Jays. Throughout The Last Poets and its follow-up, 1971’s This Is Madness, Nuriddin made black liberation feel as cool as it was urgent.

In 1973, as Lightnin’ Rod, Nuriddin released Hustlers Convention, an originating hip-hop text that would be a source of inspiration for decades of MCs, from N.W.A. and Tupac to Nas and Lupe Fiasco. Public Enemy’s Chuck D called the record the “verbal bible” for understanding the streets in the 2015 documentary he helped produce about the album. “I felt something new needed to be done to lay down the whys and wherefores of street life, its attractions and distractions,” Nurridin told The Guardian.

Rap repurposed the record’s sound and slang, but also its colorful storytelling and hustler narratives. “Hustlers Convention is a lot of what hip-hop is," Large Professor told RBMA. “It’s a lot of boastful swag and the origin of all these words and catchphrases today. It’s a staple of rap history.” Q-Tip added, “In a lot of ways, it did pre-date hip-hop.”

Nuriddin considered other early street poets like Gil Scott-Heron his students. (“I gave [Scott] one lesson and he made a career out of it, he should have come back for nine more,” he once said.) Though he had mixed feelings about rap and hip-hop, perhaps because it never truly embraced him as an architect, Nuriddin was aware of his contributions. “[Rappers] made a game out of it and they used the Hustlers Convention as if it was a whale trapped in a piranha fish pool. They all fed upon it, they got fat, and then they got fed upon,” he told Noisey in 2015.

His legacy lives on through the art form he influenced, and his narratives can be traced through years of rap songs. Jalal Mansur Nuriddin’s story is that of shepherd, ushering in a new generation of poets who ensured he wouldn’t be the last. Below, find six of Nuriddin’s most influential songs.

Lightnin’ Rod: “Sport”

The opener and conceptual centerpiece of Hustlers Convention is both a foundational moment for rapping and a sonic template. It’s been sampled by LL Cool J, the Beastie Boys, MC Lyte, Marley Marl, and Smif N’ Wessun. RZA stripped the song’s drums for Wu-Tang Clan’s “Method Man” and Jungle Brothers repurposed its entire sound on “Black Is Black,” for what would serve as Q-Tip’s rap debut.

The Last Poets: “Mean Machine”

“Mean Machine” is a fascinating display of rhythm and timing. You can hear the gears that would become the rap machine turning in Nuriddin’s calculated flows and stretched rhyme schemes. He raps over his own chanted vocals, finding pockets within his own breaking cadences.

Lightnin’ Rod: “The Bones Fly From Spoon’s Hand” + “The Break Was So Loud, It Hushed the Crowd” (1973)

One of Hustlers Convention’s most impressive gambits is how tightly wound its concept and narrative are, playing out an ongoing saga with deliberate pacing. “The Bones Fly From Spoon’s Hand” is Nuriddin’s crisp, scene-setting storytelling in action. “The Break Was So Loud, It Hushed the Crowd” is like Too $hort performing Seussian nursery rhymes about shooting dice.

The Last Poets: “White Man’s Got a God Complex”

It’s easy to hear the roots of the Public Enemy ideology—as well as other explicitly pro-black rappers like KRS-One and Melle Mel—in the spoken-word verses of this song. In fact, the militant rap group sampled the track on their 1994 album, Muse Sick-n-Hour Mess Age. But the tendrils of this Nuriddin gospel spread throughout hip-hop. The song’s messaging can be traced from Ice Cube’s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted to Joey Bada$$’ All-Amerikkkan Bada$$.

The Last Poets: “Wake Up, Niggers”

One of Nuriddin’s best songs is also one of the Last Poets’ defining texts. “Wake Up, Niggers” carries within it all the exasperation of its title, its exclamation an immediate call to action. Over patterning hands drums, he drags syllables. “Night descends as the sun’s light ends/And black comes back, to blend again/And with the death of the sun/Night and blackness become one,” he chants. “Blackness being you/Peeping through the red, the white, and the blue. Dreaming of bars, black civilizations that once flourished and grew/Hey! Wake up, niggas! Or y’all through.” The pulse of his inflections falls somewhere between the beat poetry of the ’50s and the black focus of negritude, foreshadowing not just rap but slam poetry. Jalal Mansur Nuriddin’s chants reverberate in the mind, and they continue to echo throughout culture.

#jalal mansur nuriddin#the last poets#suliaman el-hadi#suliaman el hadi#chastisment#gylan kain#david nelson#abiodun oyewole#this is madness#hustlers convention#gil scott-heron#gil scott heron#hip-hop#hip hop#mean machine#the break was so loud It hushed the crowd#the bones fly from spoon’s hand#rip#black music#music#black excellence#black genius#pitchfork

0 notes

Video

youtube

Lecture 20: Pioneers of the “spoken word,” The Last Poets were founded in 1968 by a group of New York City musicians and poets (originally consisting of Felipe Luciano, Gylan Kain, and David Nelson – although others would join the collective) sympathetic to the Black Power Movement. They were part of a larger cultural phenomenon known as the Black Arts Movement – a renaissance of African-American artistic expression that exploded in the second half of the 1960s and continued well into the 1970s. This song, “Panther,” is typical of their radical spoken word poetry of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Lecture 20: Pioneers of the “spoken word,” The Last Poets were founded in 1968 by a group of New York City musicians and poets (originally consisting of Felipe Luciano, Gylan Kain, and David Nelson – although others would join the collective) sympathetic to the Black Power Movement. They were part of a larger cultural phenomenon known as the Black Arts Movement – a renaissance of African-American artistic expression that exploded in the second half of the 1960s and continued well into the 1970s. This song, “Panther,” is typical of their radical spoken word poetry of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

1970 First Came the Words: The Last Original Poets’ Right On!

In order to understand the origins of hip hop, we must first take a look at The Last Poets, a group that emerged from the black nationalist movement in the 1960s. The original members included Gylan Kain, David Nelson, and Felipe Luciano. In their 1970 film Right On! advertised in the accompanying press release packet, The Last Poets performed poetry over the beat of a conga drum, becoming a widely credited precursor to the hip hop musical genre (Batey). The film marketed itself as authentically black, with producers claiming to make “‘no concession in language and symbolism to white audiences’” (Magliozzi). Contemporary reviews of the film argued that this was done through sound as The Last Poets spoke “to the beat of slow-moving and erotic rancor. Being niggas, they have rhythm, you see.”

With multiple flyers for the project, The Last Poets made sure their film was respected in its art form by including quotes by critics and festival mentions, but also was appealing to urban black communities by employing the vernacular in a convincing dialogue. Separate flyers catered to separate audiences. For example, the dialogue line “ this here is no jive movie” is meant to emphasize the film’s blackness through language where “talking ‘‘white’’ is equivalent to speaking Standard English and talking ‘black’ is equivalent to speaking in the black vernacular” (Johnson, 5). But the film’s marketing as “black” went beyond sound, describing blackness through inner city identity, claiming that it was a story “about the life your people had, and your peoples are the people who talk like you and crept up the same alley as you when you were nine.” This is a nod to urban life, characterized at the time by economic struggle, poverty, and deindustrialization (Rose, 48). Hence, before hip hop was even created, socioeconomic status and sound worked together to preemptively authenticate its blackness.

0 notes