#henri étienne

Text

Turns out my tablet didn't die!!! It just randomly decides on some days not to connect to my pc!

Anyways

The goober

I'M SUPER HAPPY WITH THIS SINCE THIS IS THE BIGGEST PROJECT I'VE EVER DONE IN THE LEAST AMOUNT OF TIME - ONLY 2 DAYS INSTEAD OF 3 WEEKS

I'm still not familiar with rendering and shading but YIPPEE, MY GOOFY GOOBER FRENCH BOY

Also another friend is showing interest, so that's 3 potential ocs, one being based on a Shirley Jackson story and another based on either Prometheus, Frankenstein, or Icarus since he hasn't decided yet. My lovely gf hasn't decided on her inspiration yet

Expect to see art of Salieri soon teehee

#my art yayy#limbus company oc#limbus company#limbus oc#lcb#lcb oc#oomfie company#henri étienne#idk how much tumblr nerfed the quality but try looking for a surprise on the bottom border line :]

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"To all intents and purposes she may be counted among the kings of France"

The hour that struck the death of Louis VIII was arguably the most critical in the history of the Capetian family. The new king, one day to be St Louis, was still a child. The trend of events in the previous two reigns had brought the higher nobility to realise that its independence would soon be seriously threatened. But a unique opportunity was raised to the regency of the queen-mother, Blanche of Castile, on the pretext that she was a woman and a foreigner. Yet this was not the first occasion on which the king's widow had acted as regent, nor the first on which a queen had played a part in politics. Philip Augustus had been the first Capetian not to involve his wife in the government of his realm. Before his time the queens of France had often intervened in affairs of state. Constance of Arles, not content with making married life difficult for Robert the Pious, had wanted to change the order of succession to the throne. She had led the opposition to Henri I, provoking and upholding his brothers against him, and she was perhaps responsible for the separation of Burgundy from the royal domain, to which Robert the Pious had joined it. Anna of Kiev, after the death of her husband Henri I, had been one of the regents, and it was only her second marriage, to Raoul de Crépy, that took her out of politics. Bertrada de Montfort's influence over Philip I had been notorious, and so had her hostility to the heir to the throne, whom she had even been accused of trying to poison. Adelaide of Maurienne, despite a physical personality before which Count Baldwin III of Hainault is said to have recoiled, had held considerable sway over Louis VI, procuring the disgrace of the chancellor, Etienne de Garlande, and egging on Louis to the Flemish adventure from which her brother-in-law, William Clito, was to profit so much. Eleanor of Aquitaine- as St Bernard had complained- had more power than anyone else over Louis VII as long as their marriage lasted. Louis VII's third wife, Adela of Champagne, had appealed to the king of England for help against her son Philip Augustus when he had sought to free himself of the tutelage of her brothers of Champagne. Later, reconciled with Philip, Adela had been regent during his absence from France on crusade. From the beginnings of Capet rule, the queens of France had enjoyed substantial influence over their husbands and over royal policy.

But Blanche of Castile was to play a greater role than any of her predecessors. To all intents and purposes she may be counted among the kings of France. For from 1226 until her death in 1252 she governed the kingdom. Twice she was regent: from 1226 to 1234, while Louis IX was a minor, and from 1248 to 1252 during his first absence on crusade. Between 1234 and 1248 Blanche bore no official title, but her power was no less effective. Severe in personality, heroic in stature, this Spanish princess took control of the fortunes of the dynasty and the kingdom in outstandingly difficult circumstances. For in 1226 there arose the most redoubtable coalition of great barons which the House of Capet ever had to face. Loyalty to the crown, so constant a feature of the past, seemed to be in eclipse. This was at any rate true of the barons who revolted, for they appear to have tried to seize the person of the young king himself- an attempt without parallel in Capetian history.

Blanche of Castile threw herself energetically into the struggle over her son and his throne. Taking her father-in-law, Philip Augustus, as her model, she won over half her enemies by craft, vigorously gave battle to the rest, and enlisted the alliance of the Church, including the Pope himself, and of the burgess class, which in marked fashion took the side of the royal family. Blanche was able to fend off Henry III of England, who tried to take the opportunity of recovering his ancestral lands, lost by John to Philip Augustus. She broke up the baronial coalition and reduced to submission the most dangerous of the rebels, Peter Mauclerc, Count of Brittany, and Raymond VII, Count of Toulouse. She adroitly took advantage of her victory to re-establish- this time definitively- the royal power in the south of France: her son Alphonse was married to the daughter and heiress of Raymond of Toulouse. The way was now open for the union of all Raymond's rich patrimony with the royal domain.

The Capetian monarchy emerged all the stronger from a crisis which had threatened to overwhelm it. Blanche felt it her duty not to rest on her laurels. After her son came of age she continued to make herself responsible for good and stable government. By the force of her example she drove home the lessons which Philip Augustus seems to have wanted to press upon his grandson when they had talked together. To Blanche's initiative must be credited the measures taken to suppress the dangerous revolt of Trencavel in Languedoc, as also those taken to defeat the coalition broken up after the battle of Saintes. On these occasions Louis IX did no more than carry out his mother's policy. When he went off on crusade, Blanche one more officially shouldered the government of the kingdom. She maintained law and order, prevented the further outbreak of war with England, and successfully pressed on with the policy which was to lead to the annexation of Languedoc. Likewise it was she who refurnished her son's crusade with men and money, and she took all the steps necessary for the safety of the kingdom when Louis was captured in Egypt.

Robert Fawtier- The Capetian Kings of France- Monarchy and Nation (987-1328)

#xiii#robert fawtier#the capetian kings of france#blanche de castille#queens of france#regents#louis viii#louis ix#philippe ii#constance d'arles#robert ii#henri i#anne de kiev#philippe i#bertrade de montfort#adélaïde de savoie#louis vii#étienne de garlande#st bernard#aliénor d'aquitaine#adèle de champagne

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

We are now just a few days away from the end of the submission period for the Hot Medieval and Fantasy Men Melee, and our Entrants stand numbered at 250!!!

Submissions will close on the 27th of June, so if you have a hot medieval/medieval fantasy guy (or multiple of them) you'd like to see compete, send them in!

Here is a list of our Noble and Worthy Contenders so far.

If your man isn't here, that means he has not been submitted.

The Contenders

So Far…

Adhemar, Count of Anjou [Rufus Sewell], A Knight's Tale (2001)

Prince Aemond Targaryen [Ewan Mitchell], House of the Dragon (2022-)

Alessandro Farnese [Diarmuid Noyes], Borgia: Faith and Fear (2011-2014)

King Alfred the Great [David Dawson], The Last Kingdom (2015-2022)

Ahmed Ibn Fahdlan [Antonio Banderas], The 13th Warrior (1999)

Antonius Block [Max von Sydow], The Seventh Seal (1957)

Aragorn, Son of Arathorn [Viggo Mortensen], The Lord of the Rings Trilogy (2001-2003)

King Arthur Pendragon [Alexandre Astier], Kaamelott (2004-2009)

King Arthur Pendragon [Bradley James], BBC’s Merlin (2008-2012)

Athelstan [George Blagden], Vikings (2013-2020)

Ash Williams [Bruce Campbell], Army of Darkness (1992)

Brian de Bois-Guilbert [Ciaran Hinds], Ivanhoe (1997)

Brother Cadfael [Derek Jacobi], Cadfael (1994-1998)

Carlos I [Álvaro Cervantes], Carlos Rey Emperador (2015-2016)

Prince Caspian [Ben Barnes], The Chronicles of Narnia (2010)

Cesare Borgia [Mark Ryder], Borgia: Faith and Fear (2011-2014)

Cesare Borgia [Francois Arnaud], The Borgias (2011-2013)

Prince Chauncley [Daniel Radcliffe], Miracle Workers: The Dark Ages (2020)

Prince Daemon Targaryen [Matt Smith], House of the Dragon (2022-)

Khal Drogo [Jason Momoa], Game of Thrones (2011-2019)

Lord Eddard Stark [Sean Bean], Game of Thrones (2011-2019)

Edgin [Chris Pine], Dungeons & Dragons: Honour Among Thieves (2023)

Éomer, Son of Éomund [Karl Urban], The Lord of the Rings Trilogy (2001-2003)

Étienne de Navarre [Rutger Hauer], Ladyhawke (1985)

Faramir, Son of Denethor [David Wenham], The Lord of the Rings Trilogy (2001-2003)

Finan [Mark Rowley], The Last Kingdom (2015-2022)

Sir Galahad [Michael Palin], Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975)

Galavant [Joshua Sasse], Galavant (2015-2016)

Gawain [Dev Patel], The Green Knight (2021)

Geralt z Rivii [Michał Żebrowski], The Witcher (2002)

Geralt of Rivia [Henry Cavill], The Witcher (2019-)

Sir Guy of Gisborne [Basil Rathbone], The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Sir Guy of Gisborne [Richard Armitage], BBC’s Robin Hood (2006-2009)

Prince Hamlet [Laurence Olivier], Hamlet (1948)

Hubert Hawkins [Danny Kaye], The Court Jester (1955)

King Henry II Plantagenet [Peter O’Toole], The Lion in Winter (1968)

King Henry V Plantagenet [Tom Hiddleston], The Hollow Crown (2012-2016)

Prince Henry [Dougray Scott], Ever After (1998)

Hugh Beringar [Sean Pertwee], Cadfael (1994-1998)

Inigo Montoya [Mandy Patinkin], The Princess Bride (1987)

Jareth [David Bowie], the Goblin King, Labyrinth (1986)

Jaskier [Joey Batey], The Witcher (2019-)

Prince John Plantagenet [Claude Rains], The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Lancelot [Santiago Cabrera], BBC’s Merlin (2008-2012)

Legolas Greenleaf [Orlando Bloom], The Lord of the Rings Trilogy (2001-2003)

Madmartigan [Val Kilmer], Willow (1988)

King Mark of Cornwall [Rufus Sewell], Tristan and Isolde (2006)

Mikoláš Kozlík [František Velecký], Marketa Lazarová (1967)

Merlin [Colin Morgan], BBC’s Merlin (2008-2012)

Niccolo Machiavelli [Thibaut Evrard], Borgia: Faith and Fear (2011-2014)

Prince Oberyn Martell [Pedro Pascal], Game of Thrones (2011-2019)

Peregrin “Pippin” Took [Billy Boyd], The Lord of the Rings Trilogy (2001-2003)

Pero Tovar [Pedro Pascal], The Great Wall (2016)

Ragnar Lothbrook [Travis Fimmel], Vikings (2013-2020)

Ravenhurst [Basil Rathbone], The Court Jester (1955)

Richard Cypher [Craig Horner], Legend of the Seeker (2008-2010)

King Richard [Timothy Omundson], Galavant (2015-2016)

Richard III Plantagenet [Aneurin Barnard], The White Queen (2013)

Robin Hood [Errol Flynn], The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Robin Hood [Michael Praed], Robin of Sherwood (1984)

Robin Hood [Cary Elwes], Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993)

Robin Hood [Tom Riley], Doctor Who: “The Robot of Sherwood” (2014)

Rodrigo Borgia [Jeremy Irons], The Borgias (2011-2013)

Rollo [Clive Standen], Vikings (2013-2020)

Samwise Gamgee [Sean Astin], The Lord of the Rings Trilogy (2001-2003)

Sandor Clegane [Rory McCann], Game of Thrones (2011-2019)

Sid [Luke Youngblood], Galavant (2015-2016)

Sihtric Kjartansson [Arnas Fedaravicius], The Last Kingdom (2015-2022)

Thorin Oakenshield [Richard Armitage], The Hobbit Trilogy (2012-2014)

Tom Builder [Rufus Sewell], The Pillars of the Earth (2010)

Mr. Tumnus [James McAvoy], The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (2005)

Vlad III Dracula [Luke Evans], Dracula Untold (2014)

Westley [Cary Elwes], The Princess Bride (1987)

William Thatcher [Heath Ledger], A Knight’s Tale (2001)

Will Scarlet O’Hara [Matthew Porretta], Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993)

Will Scarlett [Patrick Knowles], The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Will Scarlett [Christian Slater], Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991)

#pre tournament#submissions#will scarlett#a knights tale#the princess bride#the hobbit trilogy#guy of gisborne#daemon targaryen#robin hood prince of thieves#the last kingdom#lord of the rings#vikings#game of thrones

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

taylor swift lyrics x colors x textiles in art – blue

Tim McGraw – Taylor Swift // Portrait of Marie-Joseph Peyre – Marie-Suzanne Giroust 💙 Tim McGraw – Taylor Swift // Lady in the Boudoir – Gustav Holweg-Glantschnigg 💙 A Place in This World – Taylor Swift // Portrait of Prince William Henry, Duke of Gloucester – Jean-Étienne Liotard 💙 Dear John – Speak Now // Young Woman in a Blue Dress – Jacopo Negretti 💙 State of Grace – Red // Portrait of Mrs. Matthew Tilghman and her Daughter – John Hesselius 💙 Red – Red // An Unknown Man – Joseph Highmore 💙 All Too Well – Red // Portrait of a Man with a Quilted Sleeve – Titian 💙 Everything Has Changed – Red // Portrait of the Marquis de Saint-Paul – Jean-Baptiste Greuze 💙 Starlight – Red // Mrs. Richard Brown – John Hesselius 💙 Run – Red // Judith with the Head of Holofernes – Felice Ficherelli 💙 This Love – 1989 // Fair Rosamund – John William Waterhouse 💙 Delicate – Reputation // Miss Elizabeth Ingram – Joshua Reynolds 💙 Gorgeous – Reputation // Marguerite Hessein, Lady of Rambouillet de la Sablière – workshop of Henri and Charles Beaubrun 💙 Dancing with Our Hands Tied – Reputation // George Albert, Prince of East Frisia – Johann Conrad Eichler

Cruel Summer – Lover // Peter August Friedrich von Koskull – Michael Ludwig Claus 💙 Lover – Lover // Lady Oxenden – Joseph Wright of Derby 💙 Miss Americana & the Heartbreak Prince – Lover // Portrait of Ivan Ivanovich Betskoi – Alexander Roslin 💙 Paper Rings – Lover // Young Woman in a Blue Dress – Jacopo Negretti 💙 London Boy – Lover // Queen Henrietta Maria with Sir Jeffrey Hudson – Anthony van Dyck 💙 Afterglow – Lover // Portrait of Prince Dmitry Mikhailovich Golitsyn – Fyodor Rokotov 💙 Christmas Tree Farm – Christmas Tree Farm // Portrait of Mary Ruthven, Lady van Dyck – Anthony van Dyck 💙 invisible string – folklore // Two Altar Wings with the Visitation of Mary – unknown artist 💙 invisible string – folklore // Portrait of Madame de Pompadour – François Boucher 💙 peace – folklore // Fair Rosamund – John William Waterhouse 💙 hoax – folklore // Portrait of Charles le Normant du Coudray – Jean-Baptiste Perronneau 💙 coney island – evermore // Portrait of the Marquis de Saint-Paul – Jean-Baptiste Greuze 💙 Carolina – Carolina // Mrs. Daniel Sargent – John Singleton Copley 💙 Bejeweled – Midnights // Elsa Elisabeth Brahe – David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl 💙 The Great War – Midnights // Portrait of Françoise Marie de Bourbon – attributed to François de Troy 💙 Hits Different – Midnights // Mrs. Benjamin Pickman – John Singleton Copley

#taylor swift lyrics x colors x textiles in art#blue#taylor swift debut#speak now#speak now taylor swift#red album#red taylor swift#1989#1989 album#reputation#reputation taylor swift#lover#lover album#folklore#folklore album#evermore#evermore album#midnights#midnights album#ts edit#tswiftedit#long post#taylor swift

373 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you happen to know how often it occurred for wives of arrested deputies to share the same fate of their husbands, so either imprisoned, or condemned to death ? Do you have some examples? I'm referring to the years between 92-95. Moreover if it's not too much to ask for, could you also point out the signature of the CSP members who signed such warrants?

That’s a very interesting question, especially since no official studies seem to have been made on the subject. What I’ve found so far (and it wouldn’t surprise me if there’s way more) is:

Félicité Brissot — after the news of her husband’s arrest, Félicité, who had lived in Saint-Cloud with her three children since April 1793, traveled to Chartres. There (on an unspecified date?) she and her youngest son Anacharsis (born 1791) were arrested by the Revolutionary Committee of Saint-Cloud (the two older children had been taken in by other people) which sent her to Paris. Once arrived in the capital, Felicité was placed under surveillance in the Necker hotel, rue de Richelieu, in accordance with an order from the Committee of General Security dated August 9 1793 (she could not be placed under house arrest in her own apartment, since seals had already been placed on it). On August 11 she underwent an interrogation, and on October 13, she was sent from her house arrest (where she had still enjoyed a relative liberty) to the La Force prison. Félicité and her son were set free on February 4 1794, after six months spent under arrest. The order for her release was it too issued by the Committee of General Security, and signed by Lacoste, Vadier, Dubarran, Guffroy, Amar, Louis (du Bas-Rhin), and Voulland. Source: J.-P. Brissot mémoires (1754-1793); [suivi de] correspondance et papiers (1912) by Claude Perroud)

Suzanne Pétion — According to a footnote inserted in Lettres de madame Roland (1900), Suzanne was imprisoned in the Sainte-Pélagie prison since August 9 1793. In an undated letter written from the same prison, Madame Roland mentions that not only Suzanne, but her ten year old son Louis Étienne Jérôme is there too. I have however not been able to discover any official orders regarding Suzanne’s arrest and release, so I can’t say for exactly how long she and her son were imprisoned and who was responsible for it right now. @lanterne you wrote in this super old post that you’re waiting for a Pétion biography, did you get it? And if yes, does it perhaps say anything about Suzanne’s imprisonment in it? 😯)

Louise-Catherine-Àngélique Ricard, widow Lefebvre (Suzanne Pétion’s mother) — According to Histoire du tribunal révolutionnaire de Paris: avec le journal de ses actes (1880) by Henri Wallon, Louise was called before the parisian Revolutionary Tribunal on September 24 1793, accused “of having applauded the escape of Minister Lebrun by saying: “So much the better, we must not desire blood,” of having declared that the Brissolins and the Girondins were good republicans (“Yes,” her interlocutor replied, “once the national ax has fallen on the corpses of all of them”), for having said, when someone came to tell her that the condemned Tonduti had shouted “Long live the king” while going to execution; that everyone would have to share this feeling, and that for the public good there would have to be a king whom the “Convention and its paraphernalia ate more than the old regime”. She denied this when asked about Tonduti, limiting herself to having said: “Ah! the unfortunate.” Asked why she had made this exclamation she responded: ”through a sentiment of humanity.” She was condemned and executed the very same day.

Marie Anne Victoire Buzot — It would appear she was put under house arrest, but was able to escape from there. According to Provincial Patriot of the French Revolution: François Buzot, 1760–1794 (2015) by Bette W. Oliver, ”[Marie] had remained in Paris after her husband fled on June 2 [1793], but she was watched by a guard who had been sent to the Hôtel de Bouillon. Soon thereafter, Madame Buzot and her ”domestics” disappeared, along with all of the personal effects in the apartment. […] Madame Buzot would join her husband in Caen, but not until July 10; and no evidence remains regarding her whereabouts between the time that she left Paris in June and her arrival in Caen. At a later date, however, she wrote that she had fled, not because she feared death, but because she could not face the ”ferocious vengeance of our persecutors” who ignored the law and refused ”to listen to our justification.” I’ve unfortunately not been able to access the source used to back this though…

Marie Françoise Hébert — arrested on March 14 1794, presumably on the orders of the Committee of General Security since I can’t find any decree regarding the affair in Recueil des actes du Comité de salut public. Imprisoned in the Conciergerie until her execution on April 13 1794, so 30 days in total. See this post.

Marie Françoise Joséphine Momoro — imprisoned in the Prison de Port-libre from March 14 to May 27 1794 (2 months and 13 days), as seen through Jean-Baptiste Laboureau’s diary, cited in Mémoires sur les prisons… (1823) page 68, 72, 109.

Lucile Desmoulins — arrested on April 4 1794 according to a joint order with the signatures of Du Barran (who had also drafted it) and Voulland from the CGS and Billaud-Varennes, C-A Prieur, Carnot, Couthon, Barère and Robespierre from the CPS on it. Imprisoned in the Sainte-Pélagie prison up until April 9, when she was transferred to the Conciergerie in time for her trial to begin. Executed on April 13 1794, after nine days spent in prison. See this post.

Théresa Cabarrus — ordered arrested and put in isolation on May 22 1794, though a CPS warrant drafted by Robespierre and signed by him, Billaud-Varennes, Barère and Collot d’Herbois. Set free on July 30 (according to Madame Tallien : notre Dame de Thermidor from the last days of the French Revolution until her death as Princess de Chimay in 1835 (1913)), after two months and eight days imprisoned.

Thérèse Bouquey (Guadet’s sister-in-law) — arrested on June 17 1794 once it was revealed she and her husband for the past months had been hiding the proscribed girondins Pétion, Buzot, Barbaroux, Guadet and Salles. She, alongside her husband and father and Guadet’s father and aunt, were condemned to death and executed in Bordeaux on July 20 1794. Source: Paris révolutionnaire: Vieilles maisons, vieux papiers (1906), volume 3, chapter 15.

Marie Guadet (Guadet’s paternal aunt) — Condemned to death and executed in Bordeaux on July 20 1794, alongside her brother and his son, the Bouqueys and Xavier Dupeyrat. Source: Charlotte Corday et les Girondins: pièces classées et annotées (1872) by Charles Vatel.

Charlotte Robespierre — Arrested and interrogated on July 31 1794 (see this post). According to the article Charlotte Robespierre et ses amis (1961), no decree ordering her release appears to exist. In her memoirs (1834), Charlotte claims she was set free after a fortnight, and while the account she gives over her arrest as a whole should probably be doubted, it seems strange she would lie to make the imprisonment shorter than it really was. We know for a fact she had been set free by November 18 1794, when we find this letter from her to her uncle.

Françoise Magdeleine Fleuriet-Lescot — put under house arrest on July 28 1794, the same day as her husband’s execution. Interrogated on July 31. By August 7 1794 she had been transferred to the Carmes prison, where she the same day wrote a letter to the president of the Convention (who she asked to in turn give it to Panis) begging for her freedom. On September 5 the letter was sent to the Committee of General Security. I have been unable to discover when she was set free. Source: Papiers inédits trouvés chez Robespierre, Saint-Just, Payan, etc. supprimés ou omis par Courtois. précédés du Rapport de ce député à la Convention Nationale, volume 3, page 295-300.

Françoise Duplay — a CGS decree dated July 27 1794 orders the arrest of her, her husband and their son, and for all three to be put in isolation. The order was carried out one day later, July 28 1794, when all three were brought to the Pélagie prison. On July 29, Françoise was found hanged in her cell. See this post.

Élisabeth Le Bas Duplay — imprisoned with her infant son from July 31 to December 8 1794, 4 months and 7 days. The orders for her arrest and release were both issued by the CGS. See this post.

Sophie Auzat Duplay — She and her husband Antoine were arrested in Bruxelles on August 1 1794. By October 30 the two had been transferred to Paris, as we on that date find a letter from Sophie written from the Conciergerie prison. She was set free by a CPS decree (that I can’t find in Recueil des actes du Comité de salut public…) on November 19 1794, after 3 months and 18 days of imprisonment. When her husband got liberated is unclear. See this post.

Victoire Duplay — Arrested in Péronne by representative on mission Florent Guiot (he reveals this in a letter to the CPS dated August 4 1794). When she got set free is unknown. See this post.

Éléonore Duplay — Her arrest warrant, ordering her to be put in the Pélagie prison, was drafted by the CGS on August 6 1794. Somewhere after this date she was moved to the Port-Libré prison, and on April 21 1795, from there to the Plessis prison. She was transfered back to the Pélagie prison on May 16 1795. Finally, on July 19 1795, after as much as 11 months and 13 days in prison, Éléonore was liberated through a decree from the CGS. See this post.

Élisabeth Le Bon — arrested in Saint-Pol on August 25 1794, ”suspected of acts of oppression” and sent to Arras together with her one year old daughter Pauline. The two were locked up in ”the house of the former Providence.” On October 26, Élisabeth gave birth to her second child, Émile, while in prison. She was released from prison on October 14 1795, four days after the execution of her husband. By then, she had been imprisoned for 1 year, 1 month and 19 days. Source: Paris révolutionnaire: Vieilles maisons, vieux papiers (1906), volume 3, chapter 1.

#frev#french revolution#madame roland is of course here too but she might go in the notlikeothergirls camp in this particular instance#félicité brissot#suzanne pétion#éléonore duplay#élisabeth lebas#charlotte robespierre#théresa cabarrus#lucile desmoulins#marie françoise hébert#everyone: is held in prison from anything from two months to a whole year if not executed before then#charlotte: two weeks…#i mean i’m not surprised but…

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

ANGELIC︰DEVINE ID PACK

NAMES ⌇ abel. acher. achille. adam. adrien. adélie. aelin. alaida. alexis. alice. alya. ambroise. amelia. amour. ana. anahera. andras. angaile. ange. angel. angela. angelesse. angelette. angelica. angelina. angeline. angelique. angelissa. angelita. angeliza. angella. angelo. angelus. angelyna. angie. angé. angélique. anna. antoine. apolline. ariel. astrid. aurora. aurore. azazel. baal. behemoth. berrie. bethany. blaise. blanche. blanchesse. blanchette. blushe. bowette. cain. caleb. camille. capucine. carmen. cary. casimir. cassandra. cassiel. castiel. cathy. celeste. celestine. celine. cerberus. cerise. charmeine. cher. cherie. cherub. choirette. christian. christine. chérie. cielo. claire. claude. cloud. cloudisse. cynthia. cyril. daisy. damien. damon. danni. dina. divina. divinesse. divinette. divinne. donovan. dova. dulcengel. eden. elena. elouan. elysia. emmy. engel. enzo. erebus. eryn. estelle. esther. evangelina. evangeline. evangelista. eve. faith. felix. fiacre. fleur. fortune. francette. francis. gabriel. gabriella. gaby. gemini. genesis. ghoul. giselle. godefrey. grace. gwenaël. halo. heartette. heather. heaven. heavenelle. heavenesse. hel. helena. henri. hera. honoré. hyacinthe. icha. isaac. isabelle. isidore. jacques. jade. jennifer. jin. jocelyn. jordan. joseph. josephina. julia. kage. karine. kasdeya. katie. kenzo. keres. kilian. lacey. lambise. lamia. laura. leila. leilani. levi. leviathan. liam. lightion. lilia. lilin. lilith. lola. louis. lucia. lucien. lucifer. léo. madeleine. madeline. malachi. malvina. mal’akhi. marc. mare. marie. marin. marine. mary. mateo. maxime. melantha. michael. michelangelo. michelle. minerva. mirabelle. morgan. moros. nadia. narcisse. nazaire. nicholas. noah. noelle. octave. océane. odin. olivia. onyx. ophelia. orpheus. pheobe. pinkette. pinkion. piérre. priscilla. prosper. rainier. ramiel. raphael. ravana. raymond. robin. rogue. rosaire. roxxane. ruby. rue. ruelle. rémi. sabel. salome. salomon. samael. samuel. sara. sephora. sephtis. sera. seraph. seraphim. seraphina. seraphine. serenity. seth. skye. soan. softetta. sol. sonata. sophia. soraya. strawbette. sugarette. sylvain. sylvianne. séraphin. tatiana. theodore. timothee. tristan. uriel. ursula. valentine. valerie. venetia. vera. victor. victoria. victorien. vionetta. virtue. vivian. vivien. willow. wingette. wolf. xavier. xela. yann. yasmine. yvette. zacharie. zoe. ángel. ánxela. éloi. étienne.

PRONOUNS ⌇ abo/above. adore/adore. ae/ae. ae/aer. an/angel. angel/angel. angelic/angelic. arch/angel. archangel/archangel. arrow/arrow. aura/aura. ay/aym. ballet/ballet. beau/beau. beauty/beauty. being/being. beloved/beloved. black/black. bless/bless. bless/blessing. blessing/blessing. bloom/bloom. blue/blue. bow/bow. broke/broken. bun/bun. celeste/celestial. celestial/celestial. cher/cher. cherub/cherub. cherub/cherubim. chirp/chirp. choir/choir. clou/cloud. cloud/cloud. cold/cold. cross/cross. crown/crown. cu/cupid. cupid/cupid. curse/curse. dark/dark. deity/deity. delicate/delicate. div/divine. div/divinity. divine/divine. dove/dove. drift/drift. empty/empty. er/ero. ero/ero. ethe/ethereal. ethereal/ethereal. ey/eyr. fai/faith. faith/faith. fall/fall. fall/fallen. fate/fate. faun/fauna. feather/feather. flight/flight. float/float. flower/flower. fluff/fluff. fly/flight. fly/fly. glow/glow. gold/gold. grace/grace. gra/grace. grudge/grudge. hae/haer. ha/halo. halo/halo. harp/harp. he/hym. hea/heaven. heal/heal. heart/heart. heaven/heaven. heaven/heavenly. hell/hell. hol/holy. holy/holy. hush/hush. hx/hxm. hy/hym. hymn/hymn. id/idol. ix/ix. kind/kind. kyr/kyr. lace/lace. lamb/lamb. life/life. light/light. lo/love. lyr/lyr. lyre/lyre. melancholy/melancholy. metallic/metallic. mirror/mirror. mist/mist. misty/misty. mon/mon. moral/moral. omen/omen. peace/peace. perfect/perfection. pink/pink. pure/pure. pure/purr. radiant/radiant. ribbon/ribbon. rose/rose. sacred/sacred. saint/saint. scept/scepter. self/self. ser/seraph. seraph/seraph. seraph/seraphim. shimmer/shimmer. shine/shining. shx/hxr. silk/silk. sin/sin. sing/song. sky/sky. smite/smite. snake/snake. snow/snow. soar/soaring. soft/soft. somber/somber. sorrow/sorrow. spark/sparkle. spirit/spirit. sugar/sugar. swan/swan. sweet/sweet. taint/taint. tether/tether. thorn/thorn. thxy/thxm. thy/thyn. tru/trumpet. unholy/unholy. unknown/unknown. vae/vaer. val/valentine. vio/vior. water/water. white/white. wi/wing. wing/wing. wraith/wraith. wrath/wrath. yellow/yellow. ðe/ðim. þe/þim. ȝe/ȝim. ☀️ . ☁️ . ⛪ . ✨ . ⭐ . 🐑 . 👁️ . 👼 . 🕊️ . 🕯️ . 😇 . 🤍 . 🦢.

#⭐️lists#id pack#npt#name suggestions#name ideas#name list#pronoun suggestions#pronoun ideas#pronoun list#neopronouns#nounself#emojiself#angelkin#devinekin#wingedkin#angelcore#dovecore

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friends, enemies, comrades, Jacobins, Monarchist, Bonapartists, gather round. We have an important announcement:

The continent is beset with war. A tenacious general from Corsica has ignited conflict from Madrid to Moscow and made ancient dynasties tremble. Depending on your particular political leanings, this is either the triumph of a great man out of the chaos of The Terror, a betrayal of the values of the French Revolution, or the rule of the greatest upstart tyrant since Caesar.

But, our grand tournament is here to ask the most important question: Now that the flower of European nobility is arrayed on the battlefield in the sexiest uniforms that European history has yet produced (or indeed, may ever produce), who is the most fuckable?

The bracket is here: full bracket and just quadrant I

Want to nominate someone from the Western Hemisphere who was involved in the ever so sexy dismantling of the Spanish empire? (or the Portuguese or French American colonies as well) You can do it here

The People have created this list of nominees:

France:

Jean Lannes

Josephine de Beauharnais

Thérésa Tallien

Jean-Andoche Junot

Joseph Fouché

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand

Joachim Murat

Michel Ney

Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte (Charles XIV of Sweden)

Louis-Francois Lejeune

Pierre Jacques Étienne Cambrinne

Napoleon I

Marshal Louis-Gabriel Suchet

Jacques de Trobriand

Jean de dieu soult.

François-Étienne-Christophe Kellermann

17.Louis Davout

Pauline Bonaparte, Duchess of Guastalla

Eugène de Beauharnais

Jean-Baptiste Bessières

Antoine-Jean Gros

Jérôme Bonaparte

Andrea Masséna

Antoine Charles Louis de Lasalle

Germaine de Staël

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas

René de Traviere (The Purple Mask)

Claude Victor Perrin

Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr

François Joseph Lefebvre

Major Andre Cotard (Hornblower Series)

Edouard Mortier

Hippolyte Charles

Nicolas Charles Oudinot

Emmanuel de Grouchy

Pierre-Charles Villeneuve

Géraud Duroc

Georges Pontmercy (Les Mis)

Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont

Juliette Récamier

Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey

Louis-Alexandre Berthier

Étienne Jacques-Joseph-Alexandre Macdonald

Jean-Mathieu-Philibert Sérurier

Catherine Dominique de Pérignon

Guillaume Marie-Anne Brune

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan

Charles-Pierre Augereau

Auguste François-Marie de Colbert-Chabanais

England:

Richard Sharpe (The Sharpe Series)

Tom Pullings (Master and Commander)

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Jonathan Strange (Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell)

Captain Jack Aubrey (Aubrey/Maturin books)

Horatio Hornblower (the Hornblower Books)

William Laurence (The Temeraire Series)

Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey

Beau Brummell

Emma, Lady Hamilton

Benjamin Bathurst

Horatio Nelson

Admiral Edward Pellew

Sir Philip Bowes Vere Broke

Sidney Smith

Percy Smythe, 6th Viscount Strangford

George IV

Capt. Anthony Trumbull (The Pride and the Passion)

Barbara Childe (An Infamous Army)

Doctor Maturin (Aubrey/Maturin books)

William Pitt the Younger

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry (Lord Castlereagh)

George Canning

Scotland:

Thomas Cochrane

Colquhoun Grant

Ireland:

Arthur O'Connor

Thomas Russell

Robert Emmet

Austria:

Klemens von Metternich

Friedrich Bianchi, Duke of Casalanza

Franz I/II

Archduke Karl

Marie Louise

Franz Grillparzer

Wilhelmine von Biron

Poland:

Wincenty Krasiński

Józef Antoni Poniatowski

Józef Zajączek

Maria Walewska

Władysław Franciszek Jabłonowski

Adam Jerzy Czartoryski

Antoni Amilkar Kosiński

Zofia Czartoryska-Zamoyska

Stanislaw Kurcyusz

Russia:

Alexander I Pavlovich

Alexander Andreevich Durov

Prince Andrei (War and Peace)

Pyotr Bagration

Mikhail Miloradovich

Levin August von Bennigsen

Pavel Stroganov

Empress Elizabeth Alexeievna

Karl Wilhelm von Toll

Dmitri Kuruta

Alexander Alexeevich Tuchkov

Barclay de Tolly

Fyodor Grigorevich Gogel

Ekaterina Pavlovna Bagration

Ippolit Kuragin (War and Peace)

Prussia:

Louise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Gebard von Blücher

Carl von Clausewitz

Frederick William III

Gerhard von Scharnhorst

Louis Ferdinand of Prussia

Friederike of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Alexander von Humboldt

Dorothea von Biron

The Netherlands:

Ida St Elme

Wiliam, Prince of Orange

The Papal States:

Pius VII

Portugal:

João Severiano Maciel da Costa

Spain:

Juan Martín Díez

José de Palafox

Inês Bilbatua (Goya's Ghosts)

Haiti:

Alexandre Pétion

Sardinia:

Vittorio Emanuele I

Lombardy:

Alessandro Manzoni

Denmark:

Frederik VI

Sweden:

Gustav IV Adolph

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Prince Henry Frederick, Duke of Cumberland by Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702 - 1789)

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1799 Attr. to Antoine Gros - Étienne-Henri Méhul

(Carnavalet Museum)

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

.

From a small crowd the first night we went to see the “Vasque Olympique” take off into the Paris night sky at sunset (which ended up not going up that day due to inclement weather) to thousands of people coming to witness it in person (mostly due to seeing amazing pictures online) most nights during the 2 week of the Olympic Games.

The Olympic Cauldron has always remained on the ground in one position for the entirety of a Games, however Mathieu Lehanneur, the Cauldron’s designer, had other plans for Paris 2024. In a tribute to French pioneers Joseph-Michel Montgolfier and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier, who invented the Montgolfier-style hot air balloon, the Cauldron was designed as part of a hot air balloon. The Olympic cauldron reflects the organizers' desire to place the Games and their symbols at the center of life in the capital, making the Olympic flame visible to all and contributing to the Olympic fervor in Paris. The golden balloon and cauldron sits in the Tuileries Gardens and it is sent a hundred feet up in the air every day at sunset. In 1783, the Mongolfier balloon took off from the Tuileries in front of 400,000 rapt spectators and in the 1790s, the first-ever aerostiers brigade, the French Air Force’s hot air balloon corps, did its earliest hydrogen experiments in the Tuileries next to the Louvre. Hot air ballooning was also an Olympic sport at the 1900 Paris Olympics, with two world records set by French balloonist Henry de la Vaulx who flew all the way to Kyiv, Ukraine, traversing almost 769 miles over the course of 36 hours.

Once again I love all those French symbols/history pieces intertwined into the Olympic Games.

#celineisnotanexpatanymore#France life#Paris#paris 2024#paris olympics#CelineAndParis2024OlympicGames#CelineAndParis2024Games

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writers who knew [Marie of France Countess of Champagne] depicted her in several guises. For Chrétien de Troyes, the most elusive of contemporary writers, she was an assertive patron of romances, dictating for example the subject and meaning of the Lancelot tale. The mischievous Andreas Capellanus, who was close to Marie in the mid-1180s, drew a highly entertaining parody of Marie and the prominent women of her milieu resolving the conundrums of amatory conduct in “courts of love,” in the manner of modern advice columnists. In Hugh of Oisy’s musical performance, Marie cut a fine figure as a combatant in a tournament of elite women. It is striking how in three quite distinctive imaginative works written in the 1180s, Marie appears as an author of an Arthurian romance, a judge at a court of love, and a participant in a tournament mêlée.

Others who knew Marie well in the 1180s and 1190s remarked different aspects of her character. The Eructavit poet noted her penchant for the trappings of wealth, and addressing her directly during a performance of his religious drama, chastised her for her “largesse and lavish expenses.” [Canon] Evrat, on the other hand, a resident canon of St-Étienne who observed Marie closely in the 1190s, stressed her spiritual and moral character. Seeking to understand the deep meaning of the scriptures, he wrote, she provided him a copy of Genesis to translate into the vernacular and annotate with the findings of the latest “academic” studies. In an epilogue added after her death, Evrat penned a eulogy praising her largesse and renown, and comparing her, la gentis contesse Marie, to the three biblical Marys—“she would be the fourth.”

An entirely different side of Marie was captured by Marie’s court stenographers, William (1181–87) and Theodoric (1190–97), who made verbatim transcripts of her comments and directives while observing her deal with the practical affairs of governance: assigning revenues (“I assigned 100s. on the entry tax on wine”), resolving disputes at court (“resolved in my presence in this manner”), confirming prior transactions (“I approved this act”), registering acts done at court (“done in my presence”), consenting to feudal alienations (“I approved because it was my fief”), founding chaplaincies (“for Geoffroy, count of Brittany, my brother”), and establishing endowments (“for the anniversary of my lord and husband, Count Henry”). All of that was “done in public,” usually in the presence of her officers and witnesses. It was precisely in her capacity as ruling countess of Champagne that she continued Henry the Liberal’s example of performing in public as prince of his principality. Having observed Henry at court—just as Henry, while a very young man, had observed the conduct of his father, which earned him the reputation as the “good” Count Thibaut—Marie understood that the comital court, as the core institution of the principality, demanded her active participation, and she paid close attention to the great and the minor issues presented there for her disposition.

It should be emphasized that Henry the Liberal’s principality was only three decades old when Marie became regent in 1181, and the primary comital residence and chapel in Troyes were barely twenty years old, not yet fully implanted as the seat of a new territorial state and mausoleum of a princely lineage. Marie’s task was to preserve the principality and its institutions intact, and to assure the continuity of the lineage. And that she did. Evrat sensed both the precarious nature of her rule and her achievement in holding a firm hand on the levers of comital authority, especially during those anomalous years of the 1190s: “Well did she protect and govern the land / letting nothing slip from her hand, / she was gracious, wise, valiant, and courageous.” By all accounts, Marie projected a complex, forceful, and captivating character, one that proved a worthy counterpart to the compelling personality of Henry the Liberal. [Canon Evrat rendered homage to her in the epilogue of his Genesis translation: 'She had the heart of a man and the body of a woman'].

-Theodore Evergates, "Marie of France Countess of Champagne, 1145-1198"

#historicwomendaily#Marie of France Countess of Champagne#marie of champagne#12th century#I love this a lot#not only because of what it tells us about Marie and how she was perceived#but also because it perfectly captures the elusiveness of these historical figures#and how our knowledge of them is so dependent on narratives and propaganda and secondary perspectives#also can I just say: Evergates summing her up as 'complex forceful and captivating'? FUCK YEAH#my post

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

i just saw the post abt ur limbus oc while randomly checking the limbus tag and WOAGHH?? I LUV ITS LORE!!!!!!!!

SINCE U ALREADY EXPLAINED ITS BACKSTORY IS THERE ANY LIKE FUN FACTS OR OTHER LORE BITS U HAVE ABT IT???

I'm so happy you like the little French boy (gender neutral)

I think talking about some of the themes might be cool, so I'll do that :)

Henri's family is its version of the Little Prince's rose, and the community of the backstreets are its fox, if that makes sense. It also went exclusively by "Prince" while in the backstreets so as to protect itself from being hunted down for breaking a taboo and escaping

Due to the fact Henri doesn't want protecting and feels responsible for what happened to its metaphorical rose and fox, it has a savior/sacrificial lamb complex (which also ties into "draw me a sheep" in the book), so while Henri may be whimsical, all that whimsy is buried beneath major self loathing. It even gets them into a pretty violent scuffle with Salieri (a friend's oc based on the play Amadeus) and has the emotional availability of drywall

This last part is the fate of Henri's family so I'll spoil it again

Henri's family is sorta forced to distort as an experiment and they end up fusing together, becoming a mass of viscera, roses and thorns, and baobabs. Maybe if Henri hadn't run away, it wouldn't have ended up like this (wrong, it would've happened anyway), but not only was this an experiment, but a sort of guard for a golden bough. Henri has to be the one to let its family rest, but it throws itself at them, dying over and over, desperately trying anything to get them back. I was debating having them unfuse as they were taking their final breaths, but realistically, that probably wouldn't be possible and Henri has to face what happened. They're gone. They were too far gone for a long time. Fortunately that canto would be later down the line so it has a family within the company. It's gotta learn that it can live without trying to save someone or give up its life for a noble cause

So yeah I've been so unwell over Henri and Salieri and any time my friends wanna discuss Oomfie Company

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis VII and his great vassals

Philip Augustus owed a considerable debt to his father, not least for extending royal authority into the principalities. Louis forged links which brought the great vassals closer to a monarchy which was becoming more than one among equals, establishing the suzerainty of the Capetians. Previously the magnates had rarely attended court, only doing homage, if at all, on their borders, and providing small contingents for military service, if any. Even in the Plantagenet lands, Louis advanced the royal position. Henry Plantagenet came to Paris to give homage in return for recognition in Normandy, something previous dukes had avoided. He went again as king in 1158, acknowledging that for his French lands: "I am his man." The Plantagenet sons made frequent visits to Paris to give homage. They offered Louis lands in return for recognition, weakening their grasp on vital border territories.

Even the practice of magnates having significant functions in the palace went into decline, but now a new sort of link began to be forged. The role of the magnates was altered by the emergence of large assemblies, sometimes local, sometimes broader. The assemblies at Vézelay and Etampes, in preparation for the Second Crusade, were an important step in the significance of something akin to national assemblies.

Louis's resistance to Frederick Barbarossa also paid dividends: in Flanders, Champagne and Burgundy. Barbarossa saw Louis as a 'kinglet', and coveted the lands between their respective realms, threatening and cajoling his French neighbours. Hostile relations developed between the kings, especially during the papal schism. Again Louis's Church policy gave him advantages. His favoured candidate for the papacy, Alexander III, carried the day, and Churches in the danger area turned to him as protector, as did some of the lesser nobility. The lord of Bresse offered himself as a vassal: 'come into this region where your presence is necessary to the churches as well as to me.'

Nor was Louis easy to push against his will. Even the count of Champagne experienced the king's wrath: 'you have presumed too far, to act for me without consulting me'. Louis's third marriage, to Adela in 1160, cemented his improving relations with the house of Champagne. He had transformed French policy to ally with the natural enemies of Anjou. Adela's brothers, Theobald V count of Blois, Henry the Liberal count of Champagne, Stephen count of Sancerre, and William who would be archbishop of Reims, became vital supporters of the crown; Theobald and Henry also married Louis's two daughters by Eleanor. The crown therefore did not have to face Henry II alone. When in 1173 Louis encouraged the rebellion by Young Henry, he could call to his support the counts of Flanders, Boulogne, Troyes, Blois, Dreux and Sancerre.

In the south Louis attempted to improve his position through marriage agreements. His marriage to Eleanor gave him an interest in Aquitaine, which was not completely abandoned after the divorce. He married his sister Constance to Raymond V count of Toulouse in 1154. In 1162 Raymond declared: 'I am your man, and all that is ours is yours.' It is true that Raymond' s marriage failed, his wife complaining 'he does not even give me enough to eat', and that Raymond flirted with a Plantagenet alliance, but only to join Richard against his father. By 1176 he had returned to the Capetian fold.

Louis used marriage as a prospect to cement relations with Flanders. Louis had brought Flanders into the coalition against Henry II, and now agreement was made for his son Philip to marry Isabella of Hainault, the count of Flanders' niece. The dukes of the other great eastern principality, Burgundy, were a branch of the royal family. As Fawtier has said, it was 'the only great fief over which royal suzerainty was never contested' - at least until the time of Philip Augustus. At Louis VI's coronation, three princes of the realm had refused to give homage. By the accession of Philip Augustus, liege homage of the great vassals to the crown had become the expected practice.

Vassals of the princes sometimes turned directly to the king for aid rather than to their own lords. Many in the south sought Louis's protection, including the viscountess of Narbonne, who declared: 'I am a vassal especially devoted to your crown'. Roger Trencavel received the castle of Minerve from Louis and did homage for it, though he was a vassal of the count of Toulouse, and the castle was not even the king's to give. William of Ypres, though a vassal of

the count of Flanders, asked Louis to enfief his son Robert. Under Louis, not only were the great vassals brought closer, but Capetian influence was filtering through to a lower stratum of vassals.

Jim Bradbury - Philip Augustus, King of France, 1180-1223

#xii#jim bradbury#philip augustus king of france 1180-1223#louis vii#philippe ii#henry ii plantagenêt#frédéric barberousse#pope alexander iii#adèle de champagne#thibaut v de blois#henri i de champagne#étienne de sancerre#guillaume aux blanches mains#marie de france#alix de france#aliénor d'aquitaine#constance de france#raymond v de toulouse#philippe d'alsace#isabelle de hainaut#roger trencavel

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

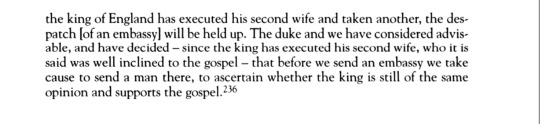

Do we know what Luther, Calvin and other Protestant leaders thought about Anne Boleyn's guilt/innocence after her fall and execution? I read somewhere that Luther was against Katharine and Henry's divorce, but I also read that Luther thought that the rise of the Reformist Anne to the English throne was a good omen).

Do we know if they current Pope, or any of the main Catholic rulers (Spain, France, Portugal) made some comment about it?

Is free from the projected journey to England, for, after these tragic occurrences there, plans have greatly changed. The second Queen, more accused than convicted of adultery, has been executed. These vicissitudes denounce the anger of God against all men, and show him that their own misfortunes and dangers should be borne with resignation.

Melancthon to Joachim Camerarius.

+

Now Sir, because [the Quene] was such a favorer of God’s word […] I tell you few men would believe that she was so abominable[…]

T. Amyot (ed.), ’A memorial from George Constantine’, in Archaeologica, 23 (1831), 50-78

+

Afterwards, in the great chamber with the others, drew a parallel between the fall of Lucifer and that of queen Anne, congratulating Sir Francis that he was not implicated.

+

Henry VIII, the League of Schmalkalden and the English Reformation, Rory McEntegart

+

Couriers of the Gospel: England and Zurich, 1531-1558, Carrie Euler

Tudor and Stuart Consorts: Power, Influence, and Dynasty (2022)

"In the years following her death, Anne had few defenders. One of them, though, was Étienne Dolet, former French embassy secretary in Venice and practically minded commentator on diplomacy. In 1538, he published an epitaph for the queen ‘falsely condemned of adultery’. The news of Anne’s arrest travelled rapidly south through Europe. It must have been a shock to the men who had toiled for six years to achieve her marriage to Henry, but then political conspiracies and swift executions were far from rare in Rome."

The Divorce of Henry VIII, Catherine Fletcher

I don't recall if Luther remarked on it specifically; although he did refer to her supplanter as an 'enemy of the gospel', so if one was so inclined, one could read into that...?

The Pope, iirc, mainly believed it presaged Anglo-Papal reconciliation (he was mistaken); Chapuys forwarded letters from Charles V where he expressed shock and horror at Henry's near-miss from regicide (whether he believed this himself or thought it was politic to express that he did...things that make you go hmmm), Mary of Hungary was skeptical yet essentially said she deserved to die regardless, so no great wrong was committed.

#anon#i will add to this if i come across anything relevant in the quotes i've saved....later#(some of these are...ambiguous; religion wise#etienne dolet was convicted of heresy but not particularly associated with other protestant leaders#francis bryan was anti-papal but not necessarily reformist otherwise#etc. but i love a good quote compilation)#george constantine was certainly a zealous evangelical tho; as was hilles etc

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The napoleonic marshal‘s children

After seeing @josefavomjaaga’s and @northernmariette’s marshal calendar, I wanted to do a similar thing for all the marshal’s children! So I did! I hope you like it. c:

I listed them in more or less chronological order but categorised them in years (especially because we don‘t know all their birthdays).

At the end of this post you are going to find remarks about some of the marshals because not every child is listed! ^^“

To the question about the sources: I mostly googled it and searched their dates in Wikipedia, ahaha. Nevertheless, I also found this website. However, I would be careful with it. We are talking about history and different sources can have different dates.

I am always open for corrections. Just correct me in the comments if you find or know a trustful source which would show that one or some of the dates are incorrect.

At the end of the day it is harmless fun and research. :)

Pre 1790

François Étienne Kellermann (4 August 1770- 2 June 1835)

Marguerite Cécile Kellermann (15 March 1773 - 12 August 1850)

Ernestine Grouchy (1787–1866)

Mélanie Marie Josèphe de Pérignon (1788 - 1858)

Alphonse Grouchy (1789–1864)

Jean-Baptiste Sophie Pierre de Pérignon (1789- 14 January 1807)

Marie Françoise Germaine de Pérignon (1789 - 15 May 1844)

Angélique Catherine Jourdan (1789 or 1791 - 7 March 1879)

1790 - 1791

Marie-Louise Oudinot (1790–1832)

Marie-Anne Masséna (8 July 1790 - 1794)

Charles Oudinot (1791 - 1863)

Aimee-Clementine Grouchy (1791–1826)

Anne-Francoise Moncey (1791–1842)

1792 - 1793

Bon-Louis Moncey (1792–1817)

Victorine Perrin (1792–1822)

Anne-Charlotte Macdonald (1792–1870)

François Henri de Pérignon (23 February 1793 - 19 October 1841)

Jacques Prosper Masséna (25 June 1793 - 13 May 1821)

1794 - 1795

Victoire Thècle Masséna (28 September 1794 - 18 March 1857)

Adele-Elisabeth Macdonald (1794–1822)

Marguerite-Félécité Desprez (1795-1854); adopted by Sérurier

Nicolette Oudinot (1795–1865)

Charles Perrin (1795–15 March 1827)

1796 - 1997

Emilie Oudinot (1796–1805)

Victor Grouchy (1796–1864)

Napoleon-Victor Perrin (24 October 1796 - 2 December 1853)

Jeanne Madeleine Delphine Jourdan (1797-1839)

1799

François Victor Masséna (2 April 1799 - 16 April 1863)

Joseph François Oscar Bernadotte (4 July 1799 – 8 July 1859)

Auguste Oudinot (1799–1835)

Caroline de Pérignon (1799-1819)

Eugene Perrin (1799–1852)

1800

Nina Jourdan (1800-1833)

Caroline Mortier de Trevise (1800–1842)

1801

Achille Charles Louis Napoléon Murat (21 January 1801 - 15 April 1847)

Louis Napoléon Lannes (30 July 1801 – 19 July 1874)

Elise Oudinot (1801–1882)

1802

Marie Letizia Joséphine Annonciade Murat (26 April 1802 - 12 March 1859)

Alfred-Jean Lannes (11 July 1802 – 20 June 1861)

Napoléon Bessière (2 August 1802 - 21 July 1856)

Paul Davout (1802–1803)

Napoléon Soult (1802–1857)

1803

Marie-Agnès Irma de Pérignon (5 April 1803 - 16 December 1849)

Joseph Napoléon Ney (8 May 1803 – 25 July 1857)

Lucien Charles Joseph Napoléon Murat (16 May 1803 - 10 April 1878)

Jean-Ernest Lannes (20 July 1803 – 24 November 1882)

Alexandrine-Aimee Macdonald (1803–1869)

Sophie Malvina Joséphine Mortier de Trévise ( 1803 - ???)

1804

Napoléon Mortier de Trévise (6 August 1804 - 29 December 1869)

Michel Louis Félix Ney (24 August 1804 – 14 July 1854)

Gustave-Olivier Lannes (4 December 1804 – 25 August 1875)

Joséphine Davout (1804–1805)

Hortense Soult (1804–1862)

Octavie de Pérignon (1804-1847)

1805

Louise Julie Caroline Murat (21 March 1805 - 1 December 1889)

Antoinette Joséphine Davout (1805 – 19 August 1821)

Stephanie-Josephine Perrin (1805–1832)

1806

Josephine-Louise Lannes (4 March 1806 – 8 November 1889)

Eugène Michel Ney (12 July 1806 – 25 October 1845)

Edouard Moriter de Trévise (1806–1815)

Léopold de Pérignon (1806-1862)

1807

Adèle Napoleone Davout (June 1807 – 21 January 1885)

Jeanne-Francoise Moncey (1807–1853)

1808: Stephanie Oudinot (1808-1893)

1809: Napoleon Davout (1809–1810)

1810: Napoleon Alexander Berthier (11 September 1810 – 10 February 1887)

1811

Napoleon Louis Davout (6 January 1811 - 13 June 1853)

Louise-Honorine Suchet (1811 – 1885)

Louise Mortier de Trévise (1811–1831)

1812

Edgar Napoléon Henry Ney (12 April 1812 – 4 October 1882)

Caroline-Joséphine Berthier (22 August 1812 – 1905)

Jules Davout (December 1812 - 1813)

1813: Louis-Napoleon Suchet (23 May 1813- 22 July 1867/77)

1814: Eve-Stéphanie Mortier de Trévise (1814–1831)

1815

Marie Anne Berthier (February 1815 - 23 July 1878)

Adelaide Louise Davout (8 July 1815 – 6 October 1892)

Laurent François or Laurent-Camille Saint-Cyr (I found two almost similar names with the same date so) (30 December 1815 – 30 January 1904)

1816: Louise Marie Oudinot (1816 - 1909)

1817

Caroline Oudinot (1817–1896)

Caroline Soult (1817–1817)

1819: Charles-Joseph Oudinot (1819–1858)

1820: Anne-Marie Suchet (1820 - 27 May 1835)

1822: Henri Oudinot ( 3 February 1822 – 29 July 1891)

1824: Louis Marie Macdonald (11 November 1824 - 6 April 1881.)

1830: Noemie Grouchy (1830–1843)

——————

Children without clear birthdays:

Camille Jourdan (died in 1842)

Sophie Jourdan (died in 1820)

Additional remarks:

- Marshal Berthier died 8.5 months before his last daughter‘s birth.

- Marshal Oudinot had 11 children and the age difference between his first and last child is around 32 years.

- The age difference between marshal Grouchy‘s first and last child is around 43 years.

- Marshal Lefebvre had fourteen children (12 sons, 2 daughters) but I couldn‘t find anything kind of reliable about them so they are not listed above. I am aware that two sons of him were listed in the link above. Nevertheless, I was uncertain to name them in my list because I thought that his last living son died in the Russian campaign while the website writes about the possibility of another son dying in 1817.

- Marshal Augerau had no children.

- Marshal Brune had apparently adopted two daughters whose names are unknown.

- Marshal Pérignon: I couldn‘t find anything about his daughters, Justine, Elisabeth and Adèle, except that they died in infancy.

- Marshal Sérurier had no biological children but adopted Marguerite-Félécité Desprez in 1814.

- Marshal Marmont had no children.

- I found out that marshal Saint-Cyr married his first cousin, lol.

- I didn‘t find anything about marshal Poniatowski having children. Apparently, he wasn‘t married either (thank you, @northernmariette for the correction of this fact! c:)

#Marshal‘s children calendar#literally every napoleonic marshal ahaha#napoleonic era#Napoleonic children#I am not putting all the children‘s names into the tags#Thank you no thank you! :)#YES I posted it without double checking every child so don‘t be surprised when I have to correct some stuff 😭#napoleon's marshals#napoleonic

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since today is Charlotte Robespierre’s 163’th birthday, I thought I’d attempt something I’ve not seen anyone else yet do, which is to write a mini biography over her entire life. I’ve already translated a study from the 1960s which deals with Charlotte, but since it’s a bit all over the place and spends almost more time describing the people Charlotte had any sort of connections with rather than Charlotte herself, I decided to try to make some more sense of things by a more chronological approach.

Marie Marguerite Charlotte de Robespierre was born in Arras on February 5 1760, around half past two in the afternoon. Her baptism record, written three days later, goes as follows:

”Today is the eighth day of the month of February, the year 1760. We priests of the parish of Saint-Étienne of towns and Diocese of Arras, have supplemented the ceremonies of the baptism for a girl born around half past two in the afternoon in said parish in the legitimite marriage of maître Maximilien-Barthélemy-François de Robespierre, lawyer at the Provincial Council of Artois, and of demoiselle Jacqueline-Margueritte Carraut, her father and mother; she was delivered by us parish priest the day after her birth, six of the same month and year as above, with the permission of the bishopric dated the same day signed by Le Roux, vicar general, and below, by ordinance Péchena. The godfather was master Charles-Antoine de Gouve, adviser to the King and his attorney for the town and city of Arras, subdelegate of the intendant of Flanders and Artois, in the department of Arras, of the parish of Saint-Jean in Ronville, and the godmother demoiselle Marie-Dominique Poiteau, widow of Sieur François Isambart, procurator to the said provincial council of Artois, of the parish of Saint-Aubert, who gave her the name Marie-Marguerite-Charlotte, and who signed with us the parish priest, and the father here present, the same act on the day and year mentioned above. The child was born on the fifth.

Marie Dominique Poiteau

De Gouve

Derobespibrre

Willart, parish priest of Saint-Etienne.”

That Charlotte wasn’t baptisted until three days after her birth may be a sign that her parents for a moment feared for her life, considering Charlotte’s three siblings — the older Maximilien (born 1758), and younger Henriette (1761) and Augustin (1763) — all were baptised the same days they had been born.

Charlotte would later recall the memory of her mother Jacqueline (1735) with fondness. ”Oh! Who would not keep the memory of this excellent mother!” she wrote in her memoirs. ”She loved us so! Nor could Maximilien recall her without emotion: every time that, in our private interviews, we spoke of her, I heard his voice alter, and I saw his eyes soften. She was no less of a good wife than a good mother.” But they did not get to keep her for long — on July 4 1764 Jacqueline gave birth to a baby who didn’t make it past his first twenty-four hours alive, and was buried in the Saint-Nicaise cemetery without having received a name. She was not to survive him for much longer, twelve days later she died as well, a few days before her twenty-ninth birthday. The funeral held the following day was, according to the mortuary act, attended by Jacqueline’s brother Augustin and Antoine-Henri Galbaut, Knight of Saint-Louis, assistant major of the Citadel, but not by her husband. In her memoirs, Charlotte reported that Jacqueline’s death had been ”a lightning strike to the heart” for him — ”He was inconsolable. Nothing could divert him from his sorrow; he no longer pleaded, nor occupied himself with business; he was entirely consumed with chagrin. He was advised to travel for some time to distract himself; he followed this advice and left: but, alas! We never saw him again; the pitiless death took him as it had already taken our mother.”

Different documents tell us that the father actually didn’t leave Arras until December 1764, five months after Jacqueline’s death, after which he sporadically appeared in his hometown, sometimes for months at a time. The last known stay is from 1772. It is nevertheless probable that he no longer was in a state to look after his children after the death of his wife, and therefore, as Charlotte recounts in her memoirs, quickly handed them over to different relatives. Charlotte and Henriette, seperated by an age gap of less than two years, were therefore sent to live with their two unmarried paternal aunts, Henriette and Eulalie de Robespierre. According to contemporary Abbé Proyart, who knew the family, the aunts ”lived in a great reputation for piety.” Maximilien and Augustin, the latter still with his wetnurse, were in their turn taken in by their maternal grandparents. According to Charlotte, the loss of their parents had left a big mark on the former:

”He was totally changed. Before that point he had been, like all children of his age, flighty, unruly, rash; but since from this time he saw himself, in the quality of eldest, as the head of the family, he became poised, reasonable, laborious; he spoke to us with a sort of imposing gravity; if he joined in our games, it was to direct them. He loved us tenderly, and there were no caresses that he did not lavish on us […] He had been given pigeons and sparrows which he took the greatest care of, and close to which he often came to pass the moments which he did not consecrate to his studies.”

The children were reunited every Sunday, during which Maximilien would show his sisters his drawings and place his sparrows and pigeons into their cupped hands. One time, Charlotte and Henriette begged him to let them have one of his birds, and after much hesitation he gave in, much to their joy. Unfortunately, some days later the girls forgot the pigeon in the garden during a stormy night, by which it perished. When he found out about it Maximilien’s tears flowed, and he rained reproaches on Charlotte and Henriette and refused to give his birds to them when he left to study in Paris. ”It was sixty years ago,” Charlotte writes in her memoirs, ”that by a childish flightiness I was the cause of my elder brother’s chagrin and tears: and well! My heart bleeds for it still; it seems to me that I have not aged a day since the tragic end of the poor pigeon was so sensitive to Maximilien, such that I was affected by it myself.”

On December 30 1768, Charlotte was sent off to Maison des Sœurs Manarre, — “a pious foundation for poor girls, who may be admitted from the age of nine to eighteen, to be fed, brought up under some good mistress of virtue and to improve oneself in lacing and sewing or in another thing which one will judge useful; to learn to read and write until they are able to serve and earn a living,” situated just across the border in Tournai (modern-day Belgium). She was actually a few months too young to be enrolled, but an exeption was made in her favor, obtained by the influence of her godfather Charles-Antoine de Gouve. Two years later Charlotte was joined at the convent school by Henriette, who in her turn was enrolled without yet having a scolarship. Perhaps this is a sign that their relatives were struggling to provide for the four orphans and thus had to send them away as quickly as possible. On October 1769, Maximilien was enrolled at the College of Louis-le-Grand in Paris, his taste for study having awarded him with a scholarship to the prestigious school, while Augustin in his turn was sent off to the College of Duoai. The children were thus dispersed and no longer saw anything of each other, except for in the summers when they were reunited in Arras. According to Charlotte these were days of great joy that passed too quickly, even if many of these years were also ”marked by the death of something cherished.” In 1770, their paternal grandmother died, in 1775 their maternal grandmother and in 1778 their maternal grandfather. 1777 saw the death of their father, who at that point was living in Munich, but it’s unknown if Charlotte and her relatives actually found out about it or not. Finally, on March 5 1780, Henriette was buried, a little more than two months after her eighteenth birthday. According to Charlotte, the death of the sister had a big impact on Maximilien, it rendered him ”sad and melancholy” and he wrote a poem in her honor. She does not, on the other hand, report how the death affected her, Henriette undeniably being the family member she had spent the most time together with… Nevertheless, she did not get a chance to say goodbye, as the names of neither her nor her brothers feature on the mortuary act of Henriette or any of the other dead relatives.

One year after Henriette’s death, Maximilien graduated from Louis-le-Grand, nine days after his twenty-third birthday. Now a fully trained lawyer, he returned to Arras to work as such. We don’t know when Charlotte left the convent school, but she soon enough joined her older brother. Augustin, however, Charlotte continued to see very little of, as Maximilien arranged for him to take over his scholarship and started his studies at Louis-le-Grand on November 3 1781. He didn’t return until 1787.

The siblings had obtained half of the 8242 livres from when their late grandfather’s brewery was sold to their maternal uncle Augustin in 1778, but they were still in a rough financial situation. In 1768 their father had resigned from any inheritance whatsoever from his mother ”both for me and my children,” a wish he had then repeated both in 1770 and 1771. In 1766, he had also borrowed seven hundred livres from his sister Henriette which he never paid back, leading to some tension between Henriette, her husband and Maximilien in 1780.

Charlotte and Maximilien at first moved into a house on Rue du Saumon, but their stay there was short — already in late 1782 they were forced to leave the house to instead move in with aunt Henriette on Rue Teinturiers. According to the memoirs of Maurice-André Gaillard, Charlotte told him in 1794 that she and Maximilien weren’t exactly welcomed with open arms by Henriette’s husband — ”It’s strange that you didn’t often notice how much [his] brusqueness and formality made us pay dearly for the bread he gave us; but you must also have noticed that if indigence saddened us, it never degraded us and you always judged us incapable of containing money through a dubious action.”

Eventually, Charlotte and Maximilien moved again, to Rue des Jésuites, and finally, in 1787, they moved from there Rue des Rapporteurs 9. There they were soon enough joined by Augustin, by now too a qualified lawyer. According to Charlotte’s memoirs, the bond between the three siblings was strong — ”good harmony would not have ceased for a sole instant to reign among us.” While her brothers worked, Charlotte took care of the house. We know the name of one of her domestics — Catherine Calmet, who helped Charlotte out for six months. When Calmet was arrested in Lille in 1788, Maximilien wrote a letter pleading in her favour: ”[Calmet’s] conduct appeared to me faultless during the time she stayed with me; I rejoice in her slightest recovery. As for the certificate you’re speaking to me about, my sister has told me that the girl brought it with her.”

The siblings had many friends. One of them was mademoiselle Dehay, who in 1782 gave Charlotte and Maximilien a cage of canaries which they both appriciated a lot. ”My sister asks me, in particular,” Maximilien wrote to her on January 22, to show you her gratitude for the kindness you have had in giving her this present, and all the other feelings you have inspired in her.” Mademoiselle Dehay would later also do other animal related favors for the two. ”Is the puppy you are raising for my sister as sweet as the one you showed me when I passed through Béthune?” Maximilien asked her in 1788. ”Whatever it looks like, we receive it with distinction and pleasure.”

Charlotte leaves a long list of Maximilien’s closest friends in her memoirs. Of those included there, important for her story as well is her brother’s fellow lawyer Antoine Buissart, ”intensely estimable savant” and his wife Charlotte. The couple lived on rue du Coclipas, a ten minute walk from Rue des Rapporteurs, and would become close with all three siblings. Another one of Maximilien’s colleagues that would play an important role in Charlotte’s life was Armand Joseph Guffroy, who, like Charlotte, witnessed Maximilien’s uneasiness when it came to the death penalty while the two worked as judges together.

Then there was the family — maternal uncle Augustin Carraut who with his wife Catherine Sabine (1740) had had four children — Augustin Louis Joseph (1762), Antoine Philippe (1764), Jean-Baptiste Guislain (1768) and Sabine Josephe (1771). The two paternal aunts Eulalie and Henriette had married in 1776 and 1777 respectively — Henriette to Gabriel-François Durut, doctor of medicine in Arras at the College d’Oratoire, Eulalie to Robert Deshorties, merchant and royal notary in Arras. Deshorties had five children from his previous marriage — two sons and three daughters. One of the daughters had according to Charlotte been courting Maximilien since 1786 or 1787. ”She loved him and was loved back. […] Many times it had been talk of marriage, and it is very probable Maximilien would have wedded her, if the the suffrage of his fellow citizens had not removed him from the sweetness of private life and thrown him into a career in politics.” However, if such plans existed, they were soon broken up by the revolution, and the step-cousin instead got engaged to another lawyer, Léandre Leducq, who she married on August 7 1792.

Charlotte was perhaps also finding love. Joseph Fouché was a science professor from Nantes, a year older than herself, who had joined her uncle Durut at the College of Arras in 1788. ”Fouché”, Charlotte writes in her memoirs, ”was not handsome, but but he had a charming wit and was extremely amiable. He spoke to me of marriage, and I admit that I felt no repugnance for that bond, and that I was well enough disposed to accord my hand to he whom my brother had introduced to me as a pure democrat and his friend.” But somehow, this engagement too ran out into the sand, and Fouché got married to Bonne Jeanne Coiquaud in 1792.

Life changed on April 26 1789, when Maximilien was elected as a deputy for the Estates General and settled for Paris for an indefinite period of time. Letters from Augustin to the family friend Antoine Buissart reveal that the he went to visit his brother in September 1789, as well as from September 1790 to March 1791. Charlotte may not have been so fond of Augustin’s trips, ”My sister must be very cross with me,” Augustin wrote to Buissart on November 25 1790, ”but she easily forgets, that consoles me, I will try to bring her what she wants.” Charlotte herself couldn’t or wouldn’t join him — ”I did not see [Maximilien] for the duration of the Constituent Assembly,” she affirms in her memoirs. In November 1791, after the closing of said assembly, Maximilien made a visit back to Arras, Charlotte, Augustin and Charlotte Buissart meeting him at the coach depot in Bapaume. In her memoirs, Charlotte could still remember the pleasure of getting to embrace her brother after not having seen him for two years. However, Maximilien’s stay was short, and on November 27 he was back in Paris to never see his hometown again.

Maximilien, like Augustin, frequently wrote long letters to Buissart, telling him about the situation developing in the capital. He did however never ask him to say hello to his siblings in them, nor do we have any conserved letters adressed from him to them. Charlotte still affirms that ”we wrote to each other often, and [Maximilien] gave me the most emphatic testimony of friendship in his letters. “You (vous) are what I love the most after the patrie,” he told me.” According to Paul Villiers, who claimed to have been Maximilien’s secretary for seven months in 1790, the latter also sent part of his deputy’s salary to ”a sister in Arras, whom he had a lot of affection of for.”

But despite the extra money, Charlotte and Augustin were having a hard time. “We are in absolute destitution,” the latter wrote to Maximilien in 1790, ”remember our unfortunate household.” Joseph Lebon, a former priest soon to be mayor of Arras, wrote to Maximilien on August 28 1792 that “the bearer of this letter, Démouliez, has planned arrangements with your brother, to procure for him the execrable silver mark.” They also had to deal with the loss of some more loved ones, as Henriette and Eulalie, the aunts that had had the raising of Charlotte and her sister, both died in 1791.

Even if Charlotte was unable to go to Paris with her younger brother, she was still politically active on a local level. This is shown through a letter dated April 9 1790 which she sent Maximilien: