#henri ii de bourbon condé

Text

Condé vs Mazarin: power and legitimacy.

By April 1649 Mazarin had survived the biggest challenge so far to his ministerial rule. A political revolt had briefly united popular unrest with the discontents of the bourgeoisie, the most senior judicial officers, and a large group of the court aristocracy. A combination of military threats and wide-ranging concessions had apparently calmed the situation; most significantly perhaps for Mazarin’s future calculations, it had demonstrated that his opponents would find it extremely difficult to militarize their opposition in any effective way. But relief was premature. For Mazarin’s new problem was that the military support he had drawn upon in early 1649 had cost him his previous near-monopoly over power and influence. Condé’s blockade of Paris had set him, as the defender of absolute royal authority —and thereby Mazarin’s ministry— directly against his own relatives and much of the great nobility. Hitherto idolized as the young military hero, he was now execrated by all those who had regarded the uprisings since August 1648 as a justified attempt to overthrow ministerial tyranny. Setting aside his personal ambitions, it was essential to his reputation that he should demonstrate as publicly and as vigorously as possible that he was no lackey of the first minister, and that his actions had been on behalf of the crown, not Mazarin.

Who then was Louis II de Bourbon-Condé, who was to become Mazarin’s nemesis for a decade from 1649? The duc d’Enghien, as he was titled until his father’s death in 1646, was no stranger to the realities of ministerial power. His father, Henri II, had rebuilt the material and political fortunes of the cadet branch of the Bourbon family on the basis of a close alliance with cardinal Richelieu after 1626. Henri de Condé provided Richelieu and his regime with the legitimizing support of a prince of the blood, and Condé in return benefited from a spectacular flow of political and territorial rewards. The benefits of the alliance were so great that he was ultimately cajoled into marrying his son, Louis II, to Richelieu’s niece, Claire-Clémence de Maillé-Brézé. The marriage, celebrated at the Palais Cardinal on 9 February 1641, was a spectacular mésalliance for the duc d’Enghien, wished upon him by his father’s ambitions. Enghien, who until 1638 had stood only three lives from the throne, shared with his father an authoritarian ideology of an absolute monarchy mediated only by the king’s ‘natural advisors’, the princes of the blood. But the association with Richelieu and his family brought him into a close, stakeholder’s connection with the ministerial regime. Through this channel would flow the financial opportunities, patronage, and influence that had been enjoyed by his father over and above what would have been his as a prince of the royal blood.

Enghien would have been an important figure in the politics of the 1640s, just as his father had been in the previous decade. But the decision in 1643 to grant him the overall command of the army operating on the north-eastern frontier was not just a reflection of his status and political connections, but a remarkable act of confidence in a young man of twenty-three with no previous experience of overall military command. Enghien was surrounded by experienced lieutenants —most notably Jean, comte de Gassion— yet much would still depend on his untested ability to demonstrate qualities of leadership and decision-making. The French army faced a Spanish invasion, poised to take the town of Rocroi, and previous encounters in the field with the veterans of the Spanish army of Flanders had not ended well for the French. Enghien and his lieutenants took the decision to engage the Spanish army in an all-or-nothing bid to try to save Rocroi. Around 7.30 am on 19 May 1643 Enghien led a cavalry charge from the right flank of the French army which shattered the Spanish horse opposing him and left the infantry centre of the Spanish army exposed to his well-executed flanking attack. The magnitude of the victory over the best troops in the Spanish monarchy was unprecedented. The young duc d’Enghien became a legend overnight, a status that he never lost in the eyes of contemporaries.

Enghien’s successive military achievements through the 1640s in different campaign theatres were not just about heroic, charismatic leadership and calculated risk-taking. There was real tactical skill, partly learnt and partly intuitive, in his military deployments, his assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of his own and enemy positions, and, above all, his ability to exploit surprise, shock, and speed to devastating advantage. Like his great contemporary, Henri de La Tour d’Auvergne, vicomte de Turenne, he recognized the fundamental importance of keeping his troops fed and equipped, and was free with his own resources to maintain supplies. Unlike Turenne, who had the well-regarded reputation of being thrifty with the lives of his own troops, Condé was unconcerned by heavy casualties in pursuit of his strategic objectives. Yet soldiers serving under his command recognized his remarkable talent for victory. On the eve of the battle of Bléneau in April 1652, one of Condé’s lieutenants wrote of the effect of the prince’s arrival, pulling the army together through the belief, above all among the common soldiers, that he was invincible.

The charisma of a young, brilliant general extended beyond the armies: in the 1640s contemporaries noted that he was regarded with both awe and considerable fear. Madame de Motteville wrote that, even after Mazarin had arrested him, ‘the reputation of M. le Prince imposed itself on everyone, and generated a curious veneration for his person, such that sightseers would go to visit the chamber where he had been imprisoned at Vincennes’. Numerous accounts confirmed that even powerful and well-established individuals found it difficult to stand up to Condé in any face-to-face confrontation, and his anger had an unpredictable character that few wished to test. The legend gained further weight from the fictional, centre-stage representation of Condé in Madeleine de Scudéry’s best-selling novel Le Grand Cyrus, published between 1649 and 1653.

The very particular danger Condé posed to Mazarin, or to any government which sought to control him, was the intractable nature of his own ambitions. His father had been manageable because he was rebuilding the Condé inheritance after its devastation in the sixteenth-century Wars of Religion, and was rehabilitating his own political reputation after rebellion and imprisonment. By the 1640s the Condé had become the wealthiest aristocratic family in France, and more territorial grants, positions, and financial rewards, though demanded, were no guarantee of further tractability. Moreover, a family strategy that aimed to consolidate the pre-eminence of the Condé-Bourbon over any other aristocratic family in France would lead Condé to target further desirable assets, especially lands and governorships, whose possession would challenge the hegemony of the crown in areas of the kingdom.

Yet at base the prince was more interested in power and influence at the centre of the state than in local power and quasi-monarchical status built up across the provinces. This desire for influence did not mean that he wished to take over government, to oust Mazarin or supplant the role of ministers in general. Indeed, the detailed, procedural business of government, the workings of the executive, would have been considered by Condé to be beneath his status, and appropriate to (interchangeable or dispensable) professionals of modest birth like Mazarin. What Condé wanted for himself was a decisive influence in the formulation of royal policy, the ability to oversee and, where necessary, shape decision-making without negotiation or compromise with other parties. During the regency he considered that this was his right by virtue of his blood, and by his acquired status as the military paladin of the young monarch. He would expect to maintain this privileged role of high-status advisor and intimate councillor after the king came of age, with the assumption that his voice would naturally outweigh others in royal decision-making. Despite the charges variously made against him by Mazarin and the court, all on the basis of notably scant evidence, Condé was far too deeply committed to the principle of divinely ordained absolute monarchy to wish to replace the king. Such an act of usurpation would radically challenge his own ideology, which linked his own status to a God-given hierarchy headed by the sovereign. Indeed, his hostility to both the Parisian frondeurs and to Mazarin was precisely because they sought to trespass upon what were the fundamental prerogatives of the monarchy.

In seeking to unravel Condé’s personality and his motivation, it is no less necessary to retrieve him from the condescension of posterity. Equipped with hindsight which sees the defeat of the Fronde as a triumph for ministerial government and its modernizing, state-building initiatives, Condé’s fate becomes a facile metaphor for the fate of the traditional ‘sword nobility’ as a whole. His reckless and inappropriate ambitions for political autonomy, personal glory, and immoderate reward were vanquished by the agent of state power, cardinal Mazarin. Defeated, forced into exile and into the service of Spain at the end of 1652, Condé was required to make a humiliating submission to Louis XIV in 1659 as the price of his ‘pardon’. After this he was reduced to an obedient vassal of the monarch. This supposedly parallels the traditional nobility as a whole, whose last irresponsible and doomed act of self-assertion was the Fronde. After this final defeat they were reduced to well-ordered servitude in the court and army of the Sun King, whose powerful, centralized state represented the triumph of bourgeois administrators, the heirs of Mazarin’s victory over the frondeurs. On this interpretation, Condé’s chief crime, if he is relieved of the charge of attempted usurpation, is setting up an ideal of autonomous political action and individual liberty in defiance of the ‘modern’ requirement for disciplined, collective obedience to the crown imposed by its faithful ministers. Indeed, even by the standards of the collective ideal of aristocratic liberty, it is suggested that Condé went too far in pursuit of uncompromising self-assertion, and helped to undermine the very values that he sought to uphold.

The real problem posed by Condé for Mazarin and his regime was not Condé’s uncontrolled individualism, his ‘folle liberté’, but the perception of contemporaries that he held more legitimate right to participate in the decision-making of a regency by virtue of his blood than did a ministerial appointee of the queen mother. Indeed, it is a remarkable triumph of a well-entrenched historiography that Condé’s actions are perceived as illegitimate attempts to challenge what is treated as the legitimate royal government personified in its first minister. By conflating Mazarin with the authority of the crown, the crucial dynamic of the conflict building up from 1643 and climaxing in the Fronde is misunderstood. Mazarin’s attempts to resist Condé’s claims to involvement in the political decisions of the regency did not deny the essential legitimacy of those claims. His approach most frequently relied on alarming both the queen mother and the king’s uncle, Gaston d’Orléans, that Condé would squeeze them out of the decision-making which was no less their right by family. Mazarin hardly needed to be reminded, and the mazarinades would have done the job for him, that his own position enjoyed no such legitimacy.

David Parrott- 1652- The Cardinal, the Prince, and the Crisis of the Fronde.

#xvii#david parrott#1652: the cardinal the prince and the crisis of the fronde#la fronde#cardinal mazarin#louis ii de bourbon condé#le grand condé#henri ii de bourbon condé#cardinal de richelieu#claire-clémence de maillé-brézé#jean de gassion#battle of rocroi#henri de la tour d'auvergne#turenne#battle of bléneau#madame de motteville#madeleine de scudéry#louis xiv#anne d'autriche#gaston d'orléans

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henri II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé.

#royaume de france#french aristocracy#henri ii de bourbon#prince de condé#maison de bourbon#bourbon condé

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

On December 5th 1560 King Francis II of France, the husband of Mary Queen of Scots, died.

Although not crowned it has to be remembered that Francis was also King consort of Scotland.

Francis was born on 19 January 1544, the eldest son of Henry II of France and Catherine de Medici, he was named for his grandfather, King Francis I.

When Francis was four years old, the Scots and French signed the Treaty of Haddington in July 1548 arranging the betrothal of Mary Queen of Scots and the dauphin Francis in return for French aid to expel the invading English. Mary Queen of Scots sailed from Dumbarton for France in the August of 1548 when she was but five years old. The young Queen was accompanied by her four Marys, the daughters of Scottish noble families, Mary Beaton, Mary Seton, Mary Fleming and Mary Livingston.

Mary spent the rest of her childhood at the court of her father-in-law, Henri II Her father-in-law, Henry II of France wrote 'from the very first day they met, my son and she got on as well together as if they had known each other for a long time'. Mary was a pretty child and brought up in the same nursery as her future husband and his siblings, became very attached to him. She corresponded regularly Mary of Guise , who remained in Scotland to rule as regent for her daughter. Much of her early life was spent at Château de Chambord. She was educated at the French court learning French, Latin, Greek, Spanish and Italian and enjoyed falconry, needlework, poetry, prose, horse riding and playing musical instruments.

Mary was the cosseted darling of the French court, the doting Henri II wrote 'The little Queen of Scots is the most perfect child I have ever seen.' He corresponded frequently with Mary of Guise, expressing his delight in his young daughter-in-law. Mary's maternal grandmother, Antoinette of Guise, in a letter to her daughter in Scotland, stated that she found Mary ' very pretty, graceful and self assured.'

Francis and Mary were married with spectacular pageantry and magnificence in the cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris, by the Cardinal Archbishop of Rouen, in the presence of Henry II, Queen Catherine de' Medici and a glittering throng of cardinals and nobles. The French courtier Pierre de Brantôme described Mary as ‘a hundred times more beautiful than a goddess of heaven … her person alone was worth a kingdom.’

Among the wedding guests was one, James Hepburn Earl of Bothwell. Francis was fourteen and Mary fifteen at the time, Francis then held the title King consort of Scotland until his death.

When Henri II was killed during a jousting contest, incidentally by Gabriel de Lorges, Comte de Montgomery, Captain of The Scots Guard, and a descendant of Alexander Montgomerie of Auchterhouse, Mary's young husband Francois ascended the throne. Francis was reported to have found the crown of France so heavy that the nobles were obliged to hold it in place for him.

The young Francis became a tool of Mary's maternal relations, the ambitious Guise family, who seized the chance for power and hoped to crush the Huguenots in France. The Huguenot leader, Louis de Bourbon, prince de Condé plotted the conspiracy of Amboise in March 1560, an abortive coup d'etat in which Huguenots surrounded the Château of Amboise and attempted to seize the King. The conspiracy was savagely put down, and its failure led to increase the power of the Guises. This alarmed the king 's mother, Catherine de Medici, who reacted by attempting to secure the appointment of the moderate Michel de L'Hospital as chancellor.

During the autumn of 1560 François became increasingly ill, and died from the complications of an ear condition, in Orléans, Loiret. Since the marriage had borne no children, the French throne passed to his 10-year-old brother, Charles IX. Mary was said to be grief-stricken Multiple diseases have been suggested as the cause of Francis' death, such as mastoiditis, meningitis, or otitis exacerbated into an abscess. Francis was buried in the Basilica of St Denis.

There was no place for the seventeen year old Mary, Queen of Scots in France, she prepared to return to her native Scotland with an uncertain future that would hold.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more …

1157 – Richard The Lion Heart, or Cœur de Lion, King of England, born (d.1199); Known to most from Sir Walter Scott's "Ivanhoe," as a young man Richard fell in love with the king of France, Philip II. Richard was an educated man who composed poetry, writing in French and Limousin. He was said to be very attractive; his hair was between red and blond, and he was light-eyed with a pale complexion. He was apparently of above average height, but as his remains have been lost since at least the French Revolution, his exact height is unknown.

Boswell's translation of King Henry II's journal records that Richard (then the Duke of Aquitaine) "remained with Philip, the king of France, who so honored him for so long that they ate every day at the same table and from the same dish, and at night their beds did not separate them. And the king of France loved him as his own soul; and they loved each other so much that the king of England was absolutely astonished at the passionate love between them and marveled at it."

Before 1948, no historian appears to have clearly affirmed that Richard was homosexual. Historian Jean Flori, however, has analysed the work of contemporary historians, and reported that they quite generally accepted that Richard was homosexual. However, not all historians agree regarding Richard's sexuality; but Flori analyzed the available contemporaneous evidence in great detail, and concluded that Richard's two public confessions and penitences (in 1191 and 1195) must have referred to the "sin of sodomy". There are contemporaneous accounts of Richard's relations with women, and Richard acknowledged one illegitimate son, Philip of Cognac. Flori thus concludes that Richard was probably bisexual, but he does agree that the contemporaneous accounts do not support the allegation that Richard had a homosexual relation with King Philip II of France.

The historian John Gillingham has suggested that theories that Richard was homosexual probably stemmed from an official record announcing that, as a symbol of unity between the two countries, the kings of France and England had slept overnight in the same bed. He expressed the view that this was "an accepted political act, nothing sexual about it; ... a bit like a modern-day photo opportunity."

Richard did later marry somewhat unenthusiastically. Upon death his widow had to sue the pope for recognition as widow, as Richard hadn't bothered to make his marriage official.

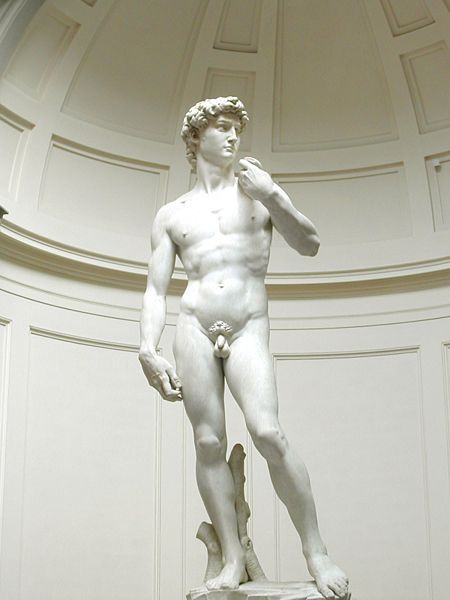

1504 – Michelangelo's David is unveiled in Florence.

1621 – Louis II De Bourbon, Prince De Condé, French General, born; Known as "the Great Condé," this greatest of French generals was an intimate of Moliere, Racine, Boileau, and La Bruyère. He also had the misfortune to be acquainted with "Madame"—the gossipy wife of Philip, duc d'Orleans—who spread the word about Conde's amours with his own sex.

Condé, a clever gent, went to great pains to establish a reputation as a great womanizer, but between the sharp tonge of Madame and the word of the well-known courtesan, Ninon de Lenclos, who was in a position to know, Condé fooled no one with his boasts.

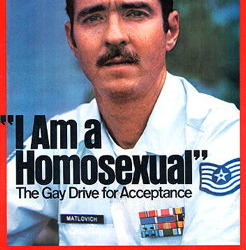

1975 – Gays In The Military: U.S. Air Force Tech Sergeant Leonard Matlovich, a decorated veteran of the Vietnam War, appears in his Air Force uniform on the cover of Time Magazine with the headline (printed in bold letters) "I Am A Homosexual." He is later given a general discharge. Matlovich, who received a purple heart and a bronze star, for bravery, was one of the first high profile members of the U.S. military to come out of the closet and challenge the ban on Gays serving. Matlovich is also famous for his statement, which is also the epitaph on his gravestone in Washington, DC's Congressional Cemetery, "When I was in the military they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one."

1958 – A California appellate court overturns the nuisance conviction of a theatre owner because of sex in the theatre.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jour 02.

Henri II de Bourbon-Condé, Prince de Condé.

Henri IV maria le jeune Henri II de Bourbon-Condé, prince de Condé, à Charlotte de Montmorency.

Il espérait ainsi pouvoir se faire la donzelle puisque le jeune Condé était réputé préférer les hommes.

instagram

0 notes

Photo

LES LUMIÈRES DE VERSAILLES #leslumièresdeversailles En 1758, les Français sont défaits à la bataille de Krefeld. Le comte de Clermont qui commande l’armée française s’enfuit jusqu'à Neuss. En entrant dans la ville, il demande à l'officier de garde : - Est-il arrivé beaucoup de fuyards ? - Non, monseigneur, vous êtes le premier. 1- UNE IDÉE DE PEINTURE Le peintre François-Hubert Drouais (1727-1775) a représenté Louis de Bourbon, comte de Clermont. Ce peintre devient successivement l'élève de son père, Hubert Drouais, de Donat Nonnotte, de Carle Van Loo, de Charles-Joseph Natoire, et de François Boucher. Reçu membre de l’Académie royale, le 25 novembre 1758, sur présentation d'un portrait de Coustou et d'un portrait de Bouchardon (aujourd'hui au Louvre) comme morceau de réception, il est rapidement appelé à Versailles. 2- UN PEU D'HISTOIRE Bien qu'entré dans les ordres, le comte de Clermont (1709-1771) obtient du pape Clément XII, en 1733, l'autorisation de porter les armes. Lieutenant général en 1735, il participe aux campagnes des Pays-Bas. Chargé du commandement de l'armée de Bohême, il est vaincu à la bataille de Krefeld (1758). Il commande l'armée du Rhin en 1758. Après les déboires rencontrés par la France face à Frédéric II de Prusse lors de la guerre de Sept Ans, il élabore des plans de remise en ordre de l'armée. Il est aussi nommé gouverneur de la Champagne le 19 septembre 1751 en remplacement de Charles de Rohan-Soubise et porte le titre jusqu'en 1769 lorsqu'il la charge à son neveu Louis VI Henri de Bourbon-Condé. 3- NE MUSIQUE D'UN BONHEUR CONTAGIEUX Regardez "François Couperin - L'Apothéose de Lully (1725)" https://youtu.be/BwO-nO9dvk4 L'apothéose de Lully (titre complet : Concert instrumental sous le titre d'Apothéose composé à la mémoire Immortelle de l'incomparable Monsieur de Lully) est une sonate en trio de François Couperin parue en 1725. La sonade, selon le terme que Couperin tentera en vain d'imposer est destinée à deux dessus de viole, basse d'archet et basse continue ou deux clavecins. François Couperin, né le 10 novembre 1668 à Paris et mort le 11 septembre 1733 à Paris, est un important compositeur, organiste et claveciniste fra https://www.instagram.com/p/CiHqxmZMoK5/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Opera Simplified #7: Les Huguenots—Notes, Act I

** Two things:

the overture (or really more of a prelude) here is not the overture Meyerbeer originally wrote, which was apparently more in a traditional overture style and was cut and replaced with this one; however, no recording has been made of the original overture, so I cannot include it here.

more important to know about this overture: yes, the tune here IS “Ein feste Bürg ist unser Gott” (“A Mighty Fortress Is Our God”), a hymn by the one, the only Martin Luther. keep the tune in the back of your head because Meyerbeer uses it as a motif throughout the opera. Yes, it is a Lutheran hymn. Yes, the vast majority of Huguenots were Calvinists. Just roll with it.

*** Admiral Gaspard II de Coligny (1519-1572) was a prominent French nobleman who converted to Protestantism in the late 1550s.

In 1562, the first of the French Wars of Religion broke out and Coligny served as a lieutenant under the Huguenot military general Louis, Prince of Condé. After Condé was executed by Catholics following his defeat, surrender, and capture at the Battle of Jarnac in 1569, Coligny became the de facto leader of the Huguenots. Well liked by King Charles IX of France, he was a voice in the French government on behalf of the Huguenots and of peace. However, this, along with (obviously) his Protestantism, made him many enemies at court.

**** As previously mentioned, Henri de Bourbon was the young Protestant King of Navarre at the time this opera takes place and was about to marry to Marguérite de Valois. Thus, it is a favor to the incoming court to have good relations with Protestant nobles.

***** This hymn, which will recur in different forms throughout the opera, is the first appearance in the opera of the previously-mentioned “Ein feste Bürg”, although in French and obviously not a 100% literal translation.

****** La Rochelle is a seaport in western France (and according to early letters by Meyerbeer, Raoul and Marcel’s hometown). During the French Wars of Religion, it was one of the Huguenots’ chief strongholds, and it declared itself independent from France in 1568. The city was famously sieged several times, most notably for about nine months in the immediate aftermath of the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. However, the conflict being referenced here is presumably a Catholic naval blockade of the city that took place in 1571, which was fiercely resisted by Huguenot forces and the city’s inhabitants.

#opera#opera tag#les huguenots#notes#meyerbeer#giacomo meyerbeer#augustin eugène scribe#émile de saint-amand deschamps

1 note

·

View note

Photo

prominent members of the Bourbon-Condé Family (16th-17th century)

#historyedit#documentaryedit#perioddramaedit#versaillesedit#mine#*#16th century#17th century#louis xiv#louis xiii#henri iv#the bourbon family#the condé family#catherine de bourbon#anne-geneviève de condé#armand de conti#louis ii de condé#henri i de condé#henri ii de condé#charles ii de bourbon#charles de bourbon#louis i de condé#antoine de bourbon#françois de conti#it's a bit of a mess rip

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Day, 20th August 1648, The Battle of Lens, The Thirty Years War.

Aug 20 1648Battle of Lens

The Battle of Lens (20 August 1648) was a French victory under Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé against the Spanish army under Archduke Leopold in the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). It was the last major battle of the war.

Lens is a fortified city in the historic region of Flanders, today a major city in the Pas-de-Calais department of northern France. The city had been captured by the French in 1647. As France began to experience a rebellion of the nobility against the leadership of Cardinal Mazarin, known as the Fronde, the Spanish saw an opportunity to retake Lens and possibly gain ground. The Prince de Condé rushed from Catalonia to Flanders and an army was cobbled together from Champagne, Lorraine as well as Paris. The French army was 16,000 men (more than half were cavalry) and 18 guns. The Spanish army was larger, comprising 18,000 men (also more than half cavalry) and 38 guns. The armies drew up, but the Spanish were on high ground and Condé decided not to attack. As the French retired, the Spanish cavalry skirmished with the French rearguard and the engagement escalated until the armies were fully engaged. The Spanish infantry pushed back the French, breaking the Gardes Françaises regiment, but the superior French cavalry were able to defeat their counterparts and envelop the center.

The danger to Dutch trade from the possession of Dunkirk by the French, the proposal of France to exchange Catalonia for the Spanish Netherlands, the declining health of Frederick Henry and his death in March 1647, all contributed to stimulate the Dutchdesire for peace. Their cooperation in 1645-6 had been but slight; they now seriously prepared to treat. Though their Treaty of Münster was not concluded until January 1648, it had been settled in principle more than a year before; and the year 1647 saw the French left alone in their northern struggle with Spain. In this year Louis de Bourbon, now Prince of Conde, was occupied in Catalonia, and Turenne was detained in Germany by the revolt of the Bernardine troops. France was exhausted, and the conquests of Dixmuyden in Flanders and La Bassee between Bethune and Lille were compensated by the loss of Menin, Armentieres, and Land- recies. In October Gassion was killed at the siege of Lens. In 1648 Conde, recalled from Catalonia, was nominated to the command in Flanders. A final effort was to be made to extort peace. Ypres had been taken and Courtrai lost when in July he was summoned to Paris in consequence of the opening troubles of the Fronde. Once more at the front, and joined by Erlach with 4000 men from the army of Breisach, he advanced to the relief of Lens, which he found had already surrendered to the Archduke Leopold. Retreating towards Bethune, he enticed the Spaniards to leave their entrenchments, and a general engagement followed according to his desire (August 20). The French army, though its right wing at first was roughly handled, was completely victorious. Both wings of the Spaniards were driven in flight. Beck was wounded and captured, refused all assistance, and died of his wounds. Leopold and Fuensaldaña fled to Douai. The Spanish infantry, no longer maintaining the tradition of those who had fallen at Rocroi, surrendered in thousands. The Spanish loss was 8000 men, 30 cannon, all their baggage, and 120 banners. Six days later Paris was in revolt. Many years were to pass before a similar victory was gained by the arms of France.

Source the World History Project website

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#DoubleTrouble Antoine of Navarre and Louis of Condé were perfect trouble makers: handsome, sauve, sophisticated, powerful, complicated, and willing to destroy the Valois at all costs. Historically: Antoine de Bourbon, King of Navarre - His son, Henry III of Navarre, became Henry IV of France. He was the first Bourbon King to rule France, after the assassination of King Henry III, of the House of Valois. Louis de Bourbon, Prince of Condé, founder of the House of Condé - Following his conversion to Protestantism, Louis was instrumental in the plot to kidnap the adolescent King Francis II in the "Conspiracy of Amboise," an unfortunate missed opportunity by the Reign writers. By 1558, when a young Mary Stuart became Queen of France with Francis II, Condé was already married with 4 children. He was 12 years Mary’s senior. #BourbonBrothers #BourbonTrouble #AntoinedeBourbon #KingofNavarre #LouisdeBourbon #PrinceofConde #Reign #HistoricalFiction #HistoricalFantasy #HistoricalDrama https://www.instagram.com/p/CZwpIA_L985/?utm_medium=tumblr

#doubletrouble#bourbonbrothers#bourbontrouble#antoinedebourbon#kingofnavarre#louisdebourbon#princeofconde#reign#historicalfiction#historicalfantasy#historicaldrama

1 note

·

View note

Text

"The Imitation of M. de Beaufort"

During the Fronde, the buccaneering cleric, Jean François Paul de Gondi, cardinal de Retz, was arrested. His colourful memoirs recounting these events, while hardly an impartial account of his political machinations, do contain many thoughtful and informative musings about the nature and meanings of disgrace. He described how minutes before his arrest, one of his friends had heard that he was to be seized and had rushed to inform him. The cardinal later commented ruefully: "He could not find me, although he only missed me by a few seconds and those seconds would without doubt have preserved my liberty." For a prince of the Church there was clearly nothing dishonourable about fleeing should the opportunity present itself. The contrast with Bassompierre's passivity is striking, and personal temperament and political context were undoubtedly significant. The maréchal believed himself to have been disgraced by his master- Louis XIII, whereas Retz and the Condé, in both 1616 and 1650, had fallen foul of the queen regent or her ministerial favourite. They were, therefore, in possession of a certain amount of leeway when it came to justifying their acts of disobedience. An angry prince de Condé had made the distinction very clear in a quarrel with Marie de Medici in the presence of Louis XIII in February 1615. When the king sought to intervene, the prince had interrupted declaring: "You are my master, I would shed the last drop of my blood in your service, but as for the queen, I cannot say the same."

For those who were prepared to resist arrest or flee to avoid it, the logical next step was to consider escape once in custody. In February 1614, César de Vendôme, the adventurous illegitimate son of Henri IV, had achieved such a feat, setting a family precedent. On the night of 31 May 1648, César's own son, François de Vendôme, duc de Beaufort, who had been imprisoned in Vincennes since the failure of the "cabale des importants", five years earlier, thrilled the public with a daring escape. In a scene worthy of Dumas, he had overpowered his guards and despite suffering a heavy fall from a rope suspended from the château walls secured his freedom. His success inspired others, and when the Grand Condé was asked what books he wished to read while a prisoner, he memorably replied: "The imitation of M. de Beaufort."

The cardinal de Retz was another to follow that illustrious example, and he late recounted his various escape attempts in some detail. Of these, that designed by his ingenious physician was particularly eye-catching. According to Retz, the doctor had the idea of filing ‘the bar of a small window which was in the chapel where I attended Mass, and to attach some sort of mechanical contraption with the aid of which I could, in truth, have been lowered quite easily from the third floor of the keep’. Unfortunately this would only take him half way down the walls of Vincennes, and the intrepid scheme had to be abandoned. Another no less imaginative plot involved the cardinal hiding in a ‘hollow’ on top of a tower which had been filled with various bits of broken masonry. Once there a friendly guard, who had previously been bought off, would attach cords to the side of the wall where Beaufort had escaped. The guard would even produce a blood-stained sword as proof that he had wounded the fleeing prisoner and as the other jailers rushed to the walls they would see a group of horsemen in the distance waiting to welcome the fugitive. As a final coup de theâtre, cannons would be fired several days later at Mézières where Retz was known to have supporters as if to signal his safe arrival. During all of this commotion, the cardinal was to be snugly hidden in the tower, fortified with supplies of bread, wine, and patience until calm was restored. With the help of the corrupted jailer and his accomplices, he would then quietly slip out of the prison dressed as a woman, a monk, or in some similarly unobtrusive disguise.

Alas all too often the best-laid plans come to naught, and an unexpected change of guard led to the blocking of a stairwell that had been crucial to the plan. Undaunted Retz had continued to scheme and when he was transferred to the fortress of Nantes his opportunity finally came. One of his servants plied the guards with drink, and the cardinal escaped after a vertiginous descent of a bastion. His celebrations were marred by an accidental pistol shot, which led to him being thrown in mid-gallop from a startled horse, fracturing, or possibly dislocating, his shoulder and leaving him free albeit in excruciating pain. To conclude his truly memorable adventure, Retz eventually made his way by ship to San Sebastián in Spain from whence he began the journey to Rome.

The cardinal could tell a good tale, but behind the derring-do there are some serious questions for the history of disgrace. On one level, his single-minded determination to escape reflects the peculiar circumstances of a Regency and especially of civil war, and Louis XIV’s later emphasis on the personal nature of his power and authority made such behaviour far more difficult to justify.

Julian Swann- Exile, Imprisonment or Death- the Politics of Disgrace in Bourbon France.

#xvii#julian swann#exile imprisonment or death: the politics of disgrace in bourbon france#cardinal de retz#bassompierre#louis xiii#marie de médicis#henri ii de bourbon condé#césar de vendôme#françois de vendôme#duc de beaufort#cabale des importants#louis ii de bourbon condé#la fronde

0 notes

Photo

On December 5th 1560 King Francis II of France, the husband of Mary Queen of Scots, died.

Although not crowned it has to be remembered that Francis was also King consort of Scotland.

Francis was born on 19th January 1544, the eldest son of Henry II of France and Catherine de Medici, he was named for his grandfather, King Francis I.

When Francis was four years old, the Scots and French signed the Treaty of Haddington in July 1548 arranging the betrothal of Mary Queen of Scots and the dauphin Francis in return for French aid to expel the invading English. Mary Queen of Scots sailed from Dumbarton for France in the August of 1548 when she was but five years old. The young Queen was accompanied by her four Marys, the daughters of Scottish noble families, Mary Beaton, Mary Seton, Mary Fleming and Mary Livingston.

Mary spent the rest of her childhood at the court of her father-in-law, Henri II Her father-in-law, Henry II of France wrote ‘from the very first day they met, my son and she got on as well together as if they had known each other for a long time’. Mary was a pretty child and brought up in the same nursery as her future husband and his siblings, became very attached to him. She corresponded regularly Mary of Guise , who remained in Scotland to rule as regent for her daughter. Much of her early life was spent at Château de Chambord. She was educated at the French court learning French, Latin, Greek, Spanish and Italian and enjoyed falconry, needlework, poetry, prose, horse riding and playing musical instruments.

Mary was the cosseted darling of the French court, the doting Henri II wrote 'The little Queen of Scots is the most perfect child I have ever seen.’ He corresponded frequently with Mary of Guise, expressing his delight in his young daughter-in-law. Mary’s maternal grandmother, Antoinette of Guise, in a letter to her daughter in Scotland, stated that she found Mary ’ very pretty, graceful and self assured.’

Francis and Mary were married with spectacular pageantry and magnificence in the cathedral of Notre Dame, Paris, by the Cardinal Archbishop of Rouen, in the presence of Henry II, Queen Catherine de’ Medici and a glittering throng of cardinals and nobles. The French courtier Pierre de Brantôme described Mary as ‘a hundred times more beautiful than a goddess of heaven … her person alone was worth a kingdom.’

Among the wedding guests was one, James Hepburn Earl of Bothwell. Francis was fourteen and Mary fifteen at the time, Francis then held the title King consort of Scotland until his death.

When Henri II was killed during a jousting contest, incidentally by Gabriel de Lorges, Comte de Montgomery, Captain of The Scots Guard, and a descendant of Alexander Montgomerie of Auchterhouse, Mary’s young husband Francois ascended the throne. Francis was reported to have found the crown of France so heavy that the nobles were obliged to hold it in place for him.

The young Francis became a tool of Mary’s maternal relations, the ambitious Guise family, who seized the chance for power and hoped to crush the Huguenots in France. The Huguenot leader, Louis de Bourbon, prince de Condé plotted the conspiracy of Amboise in March 1560, an abortive coup d'etat in which Huguenots surrounded the Château of Amboise and attempted to seize the King. The conspiracy was savagely put down, and its failure led to increase the power of the Guises. This alarmed the king ’s mother, Catherine de Medici, who reacted by attempting to secure the appointment of the moderate Michel de L'Hospital as chancellor.

During the autumn of 1560 François became increasingly ill, and died from the complications of an ear condition, in Orléans, Loiret. Since the marriage had borne no children, the French throne passed to his 10-year-old brother, Charles IX. Mary was said to be grief-stricken Multiple diseases have been suggested as the cause of Francis’ death, such as mastoiditis, meningitis, or otitis exacerbated into an abscess. Francis was buried in the Basilica of St Denis.

There was no place for the seventeen year old Mary, Queen of Scots in France, she prepared to return to her native Scotland with an uncertain future that would hold.

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

EN VENTE ÉPOQUE : 18ème siècle STYLE : Louis XV Transition LONGUEUR : 90cm LARGEUR : 72cm MATÉRIEL : huile sur toile PRIX: 5800€ ANTIQUAIRE Caudroit Téléphone: +33662098900 🐆🐆🐆🐆🐆🐆🐆🐆🐆🐆 Anticswiss.com platform Description Détaillée Maison de Savoie. Reine de Sardaigne, Portrait de Polixena par Maria Giovanni Clementi (1706-1735) Toile de 73 cm par 55 cm Cadre ancien de 90 cm par 72 cm Très bel example du portrait italien du début du 18è que cette toile très certainement peinte par Maria Giovanni Clementi qui nous propose la reine de Sardaigne vers 1730. La reine nous est montrée sous ses plus beaux atours, elle est vétue d'une robe en soie très richement brodée de fil d'argent, un manteau brodé de fil d'or à la doublure en hermine posé sur le bras. Les bijoux sont quelques examples des joyaux des Bourbon d'Espagne La Maison de Savoie est une dynastie européenne ayant porté les titres de comte de Savoie (1033), de duc de Savoie (1416), prince de Piemont, roi de Sicile (1713), roi de Sardaigne (1720) et roi d'Italie (1861). Polissena d'Assia-Rheinfels-Rotenburg (1706-1735) Née à Langenschwalbach, en Allemagne aujourd’hui, a 10 frères et soeurs. Sa soeur Caroline a été une des femmes proposées en mariage à Louis XV, elle a en fait épousé le duc Louis-Henry de Bourbon-Condé. Encore très jeune, elle est proposée en mariage à Carle Emanuele , prince héréditaire de Savoie après la mort de sa première épouse-mariage en 1724. En 1728, après la mort de sa belle-mère Anna Maria d'Orléans, elle devient la femme la plus importante et la plus influente de la cour de Savoie, En 1730,son beau-père Vittorio Amedeo II abdique en faveur de son fils Carlo Emanuele. Polissena devient reine de Sardaigne, princesse du piemont, duchesse de savoie... Elle décède à l'âge de 28 ans. Mari giovanna Clementi (1692-1761)) Elle est née à Turin, la fille d'un chirurgien.Elle a été formée à Turin avec le peintre de la cour Giovanni Battista Curlando, qui lui a conseillé de se spécialiser dans les portraits. (presso Gaiba) https://www.instagram.com/p/CFPVUGPHWkd/?igshid=1oahvaksvnygl

0 notes

Photo

La Bataille de Seneffe. Détail représentant le jeune duc d'Enghien (Henri III Jules de Bourbon-Condé) sauvant son père, le Grand Condé (Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé). by Benigne Gagneraux

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Henri II de Bourbon-Condé et sa famille, vitrail de la Collégiale Saint-Martin de Montmorency

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

LES LUMIÈRES DE VERSAILLES « Un Prince [Condé] qui a honoré la Maison de France, tout le nom français, son siècle, et pour ainsi dire l’humanité tout entière. » BOSSUET (1627-1704), Oraison funèbre de Louis de Bourbon (1686) 1/ UNE IDÉE DE PEINTURE Louis II de bourbon (1621-1686), prince de condé, devant le champ de bataille de Rocroi de Justus van Egmont ,peintre flamand (1601-1674). Après un voyage en Italie, qu'il commença en 1618, il entra dans l'atelier de Rubens. En 1628, Justus van Egmont alla s'établir à Paris, où il devint peintre de Louis XIII, puis de Louis XIV. Très apprécié en France comme portraitiste, Justus Van Egmont participa également aux grandes décorations dirigées par Simon Vouet. 2/ UN PEU D'HISTOIRE MODERNE On oublie sa Fronde et son alliance avec l’Espagne ennemie, pour ne plus rappeler que le jeune vainqueur de Rocroi et de Nördlingen avec Turenne, puis ses campagnes de Franche-Comté et d’Alsace au service de Louis XIV. Le Grand Condé, à l’inverse de Turenne mort à 65 ans au combat, acheva au même âge sa vie à Chantilly, entouré de poètes et d’écrivains (Boileau, Racine). 3/ UNE MUSIQUE D'UN BONHEUR CONTAGIEUX Henry Madin (1698-1748) 'Te Deum', Grand Motet HM 28 https://youtu.be/LC88V1FLkFc Gentilhomme d'origine irlandaise, Henry Madin apprend la musique à Verdun dans l'Est de la France. À partir de 1741, protégé par Louis XV, Madin obtient une charge de Gouverneur des Pages à la Chapelle Royale du Château de Versailles. Madin est l’auteur de nombreuses œuvres de musique sacrée. Il est également l'auteur d'un ouvrage de théorie musicale, le Traité de contrepoint simple, ou Chant sur le Livre (Paris, 1742). Tout comme les compositeurs français de l'époque, il écrivit un Te Deum. #leslumièresdeversailles https://www.facebook.com/groups/716146568740323/?ref=share_group_link https://www.instagram.com/p/CWBGRYusGyQ/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes