#hms hecla

Text

Situation of H.M. Ships Hecla & Fury in the arctic, August 1, 1825, by Edward Francis Finden & John Murray Head, 1825

189 notes

·

View notes

Text

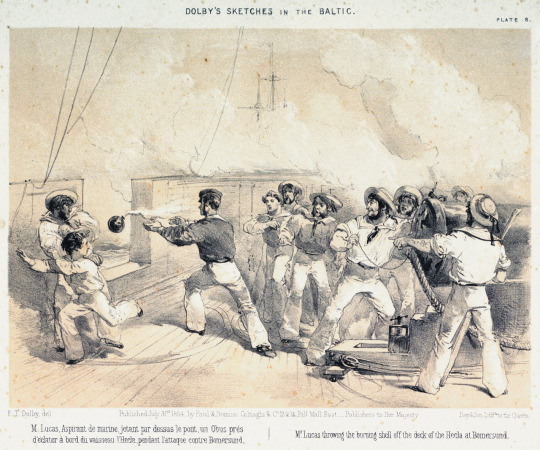

Midshipman Monday: Mr. Lucas Saves the Day

'Mr Lucas throwing the burning shell off the deck of the Hecla at Bomersund' 1854 print (NMM).

In the Crimean War, Midshipman Charles Lucas became the first person to be awarded a Victoria Cross, the highest recognition for gallantry in the British Empire, when he seized a live shell with the fuse still hissing aboard HMS Hecla and flung it overboard during the Battle of Bomarsund in August 1854.

Another illustration of the heroic Midshipman Lucas, from his entry on Victoria Cross: The Men Behind the Medals, which also has a biography. Lucas died peacefully at home at 80 years of age in 1914, just as the First World War was breaking out.

A view from the quarter deck of HMS Bulldog in the Battle of Bomersund (Wikimedia Commons). Midshipmen stand at left.

#midshipman monday#age of steam#1850s#age of sail#crimean war#royal navy#naval history#military history#victoria cross#charles lucas#battle of bomersund#midshipmen#dressed to kill

107 notes

·

View notes

Note

What type of ships were the Erebus and the Terror?

Hi!

I see that the great @the-golden-vanity has answered this very well (I'm getting to this ask a bit late!) so I'll try to complement their post – which is here!

Put briefly, they were bomb ships, ie ships which had been designed to fire exploding mortar shells (larger than cannonballs - here's an example) and thus were broad, squat, and designed to withstand heavy recoil. They were then significantly strengthened with thicker hulls and inner crossbeams, somewhat rebuilt, and had all but two of their guns removed, for Arctic service.

In terms of size the bomb ships were rather small warships - for discovery service they generally carried a complement of about 60 men per ship. (In war I believe they'd carried more, in order to man the guns.) When they were on exploration service, the base pay of their officers was at the same rate as those of 6th rate warships, ie, the smallest class of ship which was ranked as a ship of the line. (But Arctic service, due to its hazardous nature, conferred double pay.)

Erebus belonged to the Hecla class, ie was modeled after HMS Hecla, while Terror belonged to the Vesuvius class. They were almost the same size, with Erebus being slightly larger.

#hms erebus#hms terror#im visiting my mum so i haven't got any of my books with me; so if ive misremembered anything pls bear with me! 😄

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

@nomilkinmyteaplease has sweetly invited me to this tag game. And so I shall oblige.

Last Song: Bones by Low Roar

Currently Reading: Barrow's Boys and May We Be Spared To Meet On Earth. My heart is sobbing and my spirit is yearning.

Last Movie: Dune

Currently Watching: Nothing! I am not very good with watching media. I would like to watch "Around the World in 80 Days"

Currently Craving: Orange Chicken

Currently Consuming: Nothing quite yet. I am cooking dinner though. It is in the oven!

Three Ships: The Hecla. HMS Erebus. HMS Terror. (Oh I know I know.)

How about this: Fitzier. Jopzier. Joplittle.

First Ship: The First Ship I fell in love with was the HMS Prince of Wales (1860)

Otherwise you may be looking for: Rodya x Dmitri (Crime and Punishment).

Favorite Color: Pale Blues and Sea Blues

Currently Working On: Fanfiction

Thank you so kindly! I will be tagging: @theturntechgod, @aurpiment, @jirving, @georges-chambers, @haredjarris, @caleblandrybones, @bridglars, @wllipt, @skelelephant, @brainyraccoons, @the-golden-vanity

And by all means, please help yourself! Share away!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rediscovered Art Reveals Falklands War History

In a remarkable discovery at HMS Raleigh, staff rediscovered a long-forgotten painting depicting a harrowing scene from the Falklands War, sparking interest and deep reflection among veterans, staff, and the wider community. This find, made in a disused classroom, illuminates a critical chapter in British military history, bringing to life the stark realities of war through the medium of art.

A Forgotten Treasure in HMS Raleigh

Discovery by Defence Infrastructure Organisation

The Defence Infrastructure Organisation (DIO), responsible for maintaining Defence estates, played a crucial role in uncovering this historical artifact. In Building 110, also known as the Fieldhouse block - named in honor of Admiral Fieldhouse, who spearheaded the retaking of the Falkland Islands - someone discovered the painting. It had remained hidden and neglected for years in a classroom that had fallen out of use.

The Artwork's Poignant Depiction

The painting powerfully portrays the Bluff Cove Air Attacks, a pivotal and tragic moment during the Falklands War. It strikingly features the burning HMS Sir Galahad, a poignant reminder of the conflict's deadliest incident. In this attack, 56 British personnel lost their lives, with 48 dying from the bombing of HMS Sir Galahad alone. The artwork serves as a stark and moving tribute to those who perished and the brutal reality of war.

The Mystery of the Artist

The Search for the Creator

Following its discovery, the painting has ignited a wave of curiosity about its unknown creator. The artist’s identity remains shrouded in mystery, raising questions about whether they were a witness to the conflict and what inspired them to create such a vivid depiction of war.

Jon Rickman-Dawson's Discovery

Jon Rickman-Dawson, the DIO Facilities Manager at HMS Raleigh, came across this evocative artwork during an inspection of the disused building. His accidental discovery has led to an intriguing quest to uncover the story behind this painting, and to acknowledge and celebrate the artist’s contribution to HMS Raleigh’s historical narrative.

A New Home and Purpose

The Painting's Journey to the Trainees' Bar

Now prominently displayed in the Trainees’ Bar at HMS Raleigh, the painting measures an impressive 20ft by 6ft. It has become a historical artifact for staff, recruits, and their families to contemplate and appreciate, especially during significant occasions like Passing Out ceremonies. The artwork not only decorates the bar but also serves as an educational piece, offering insights into the conflict and the harsh realities of war.

Refurbishment and Preservation

The Establishment Services team, affectionately known as the ‘Buffers’, actively refurbished the painting before its installation in the new location. They meticulously cleaned, re-stained, and treated the frame, ensuring this poignant piece of history is preserved and appreciated by future generations.

Emotional Resonance and Pride

Mark Eve's Personal Connection

The painting holds a special significance for Mark Eve, a former Chief Petty Officer in the Royal Navy who served during the Falklands War. His personal experiences on HMS Hecla, an ambulance ship during the conflict, resonate deeply with the scenes depicted in the artwork. Upon seeing the painting, Eve experienced a flood of emotions, feeling both a profound sense of pride and a poignant reminder of his duty during that tumultuous time.

Base Commander Sean Brady's Interpretation

Sean Brady, the base commander at HMS Raleigh, keenly seeks to understand the artist's perspective and believes the painting vividly captures the harsh reality of conflict, a sentiment echoed by many who view it. Consequently, the quest to find the artist and understand their intentions stems from a desire to connect more deeply with the narrative of the Falklands War as depicted in the painting.

A Call to Uncover the Artist's Identity

The Timeframe of Creation

It is believed that the artwork was created sometime between 1982 and 2010, likely by someone who was present during the air attacks, evidenced by the detailed and emotionally charged nature of the painting.

Seeking Information

The DIO is actively seeking information about the artist or the origins of the painting and, therefore, encourages anyone with knowledge to reach out via email or through DIO's social media channels. This call for information is not merely about solving a mystery; it's fundamentally about honoring the artist's contribution to preserving a crucial part of military history.

Sources: THX News & Defence Infrastructure Organisation.

Read the full article

#ArtistIdentitySearch#BluffCoveAirAttacks#DefenceInfrastructureOrganisation#FalklandsConflictRepresentation#FalklandsWarHistory#HMSRaleighArtwork#HMSSirGalahad#MilitaryArtDiscovery#RediscoveredFalklandsWarPainting#VeteranEmotionalResonance

0 notes

Photo

“A Brutal Day” 80 Years Ago, Today - (Thurs) Nov 12th, 1942: Convoy UGF-1, anchored 4 miles off Casablanca, Morocco, continues to be carved up by U-Boats. U-130 (Type IXC), under U-Boat Ace Ernst Kals, fires a spread of 5 torpedoes, sinking 3 critically important American troop ships. They are: USS Edward Rutledge (AP-52, Pic 1) with 15 men dead; USS Hugh L. Scott (AP-43, Pic 2), 59 Dead, 60 Survivors; and USS Tasker H. Bliss (AP-42, Pic 3), with 31 dead and 204 survivors. 200 miles northwest of Casablanca, U-515 (IXC) scores on a pair of British warships in support of Operation Torch. She sinks the destroyer tender HMS Hecla (F-20, Hecla Class, Pic 4) with 279 dead, & 268 survivors. She also hits the destroyer HMS Marne (G-35, M-Class, Pic 5) blowing her stern clean off (Pic 6). Only 13 men are killed, and Marne is towed into Gibraltar for repairs. 10 miles off Oran, Algeria U-593 (VIIC) hits convoy KMS-2, sinking the British steamer “SS Browning” (Pic 7) when her cargo of ammunition explodes. Amazingly, only one man is killed, and 61 are rescued. For her efforts, U-593 will endure a 16-hour depth-charge attack, and survive. Further east, the British sloop HMS Stork (U-81, Bittern-Class, Pic 8) is torpedoed by U-77 (VIIC) just off Fouka, Algeria. Despite her small size, she survives the hit. Leaving the bloody waters around Africa, we go to the Caribbean, where the diminutive little US Navy Gunboat USS Erie (PG-50, Erie-Class, Pic 9) is sunk by U-163 (IXC) in an attack on Convoy TAG-20 barely 3 miles south of Curacao. 7 men are killed, but 173 others are rescued. Last, we go to the middle of nowhere in the North Atlantic – the nearest land is Ireland, 654 miles to the east. The Panamanian freighter “SS Buchanan” (Pic 10) is sunk by U-224 (VIIC). Miraculously, all 73 crewmen are rescued. The Germans don’t get off so easily today; they lose 2 U-Boats. In The Baltic,the brand new U-272 (VIIC), in training, sinks after a collision with U-634 (VIIC). 19 men escape, but U-272 will take 29 Officers and Men with her. Meanwhile, U-660 (VIIC) is depth-charged and sunk by the Royal Navy 32 miles northwest of Oran; 2 Dead, 45 Survivors. Just another day... (at Fort Hancock, New Jersey) https://www.instagram.com/p/Ck4sDISN2fm/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Bonus:

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

HMS Hecla in Baffin Bay, from William Edward Parry, Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage, 1821. Not pictured: a Marryat character trapped in an iceberg in suspended animation.

The five months had elapsed, according to my calculations, when one morning I heard a grating noise close to me; soon afterwards I perceived the teeth of a saw entering my domicile, and I correctly judged that some ship was cutting her way through the ice. Although I could not make myself heard, I waited in anxious expectation of deliverance. The saw approached very near to where I was sitting, and I was afraid that I should be wounded, if not cut in halves; but just as it was within two inches of my nose, it was withdrawn. The fact was, that I was under the main floe, which had been frozen together, and the firm ice above having been removed and pushed away, I rose to the surface. A current of fresh air immediately poured into the small incision made by the saw, which not only took away my breath from its sharpness, but brought on a spitting of blood. Hearing the sound of voices, I considered my deliverance as certain. Although I understood very little English, I heard the name of Captain Parry frequently mentioned—a name, I presume, that your highness is well acquainted with.

“Pooh! never heard of it,” replied the pacha.

“I am surprised, your highness; I thought every body must have heard of that adventurous navigator. I may here observe that I have since read his voyages, and he mentions, as a curious fact, the steam which was emitted from the ice—which was nothing more than the hot air escaping from my cave when it was cut through."

— Frederick Marryat, The Pacha of Many Tales

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#age of sail#william edward parry#arctic exploration#the pacha of many tales#i can't find this reference to steam coming from the ice in parry's narratives#the character speaking is a notorious liar#in case it wasn't obvious#polar expeditions#hms hecla#huckaback

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Una moda pasajera

El día 10 de julio de 1887 hacía su entrada al puerto de Barcelona el transporte de torpederos HMS Hecla de la Royal Navy, que al mando del capitán Edmund Frederick Jeffreys tardó tres días en realizar la travesía desde Malta. El HMS Hecla se sumó a la escuadra de la Royal Navy que se hallaba en el puerto, estos barcos eran los acorazados HMS Alexandra en cuyo mástil enarbolaba la insignia del…

View On WordPress

#1887#Conde de Venadito#Foudre#HMS Hecla#HMS Vulcan#portatorpederos#royal navy#Torpederos de 2ª clase#USS Aconitus#USS Iris#USS Tom Green Country#Veliky Knyaz Konstant#Vietnam

0 notes

Text

a primer on that handsome lad, james clark ross

here’s a bunch of stuff that i’ve learned the past year about the handomest man in the navy, sir james clark ross. we don’t know about him much, and from what we do know, it’s all in relation to the franklin expedition. so here’s a long list of trivia about the man who located the north magnetic pole, the “discoverer” of the antarctic, and francis crozier’s best friend.

feel free to use excessively (i.e. pls write him in fanfic tnx)

early life:

was born on 15th april 1800 to george and christian clark ross. his siblings were andrew clark, george clark, isabella, and marion, and two siblings who died in infancy.

his mother died in 1808 and the ross children were raised more by their uncles than their father.

career:

joined the navy at 11yo. his first ship was the hms briseis, with his uncle john ross as captain, was promoted to midshipman and master’s mate

moved with his uncle to hms actaeon then hms driver

joined john ross’s first and last navy-backed arctic expedition in 1818 (hms isabella)

joined three arctic expeditions under william edward parry (hms hecla, hms fury) from 1819 to 25, was promoted to lieutenant aged 22, then to commander aged 27. this was rather quick by navy standards. in comparison, fitzjames was dodgily promoted to commander at age 29.

joined parry’s 1827 attempt at the north pole as his second (hms hecla, endeavour)

joined john ross’s privately funded arctic expedition in 1829-33 (victory), then was promoted to captain at age 34. for reference, crozier was made captain at 44yo.

embarked on a magnetic survey of great britain from 1835 to 38

was briefly sent on a rescue mission in 1836 to save 11 trapped whalers in arctic waters (cove). he was offered a knighthood afterward but he declined.

led an exploratory voyage in 1839 to antarctica, which lasted four years (hms erebus and terror)

retired from active service at age 43 and was knighted the following year

was the first choice for the 1845 arctic expedition but declined

led an 1848 rescue attempt for the franklin expedition (hms enterprise and investigator), which was almost catastrophic and ended prematurely

was promoted to rear admiral of the red in 1856

physicality:

nearly had his spine crushed while hauling when a boat slipped and pinned him against an outcrop. jcr and the 1827 crew endured hauling boats through uneven ice, large floes, thin surfaces, slush, and rain.

broke two ribs during one of the many sledging trips he took during 1830 and still managed to walk for nine hours the following day

casually walked away from his group to survey an inlet. alone! in the arctic!!! and came back exhausted around midnight. he had travelled 50 miles that day.

spent twenty three days sledging in the area of boothia peninsula. jcr gazed out across the ice from cape felix and remarked on the heavy stream of pack ice (which will trap the franklin expedition years later).

he further sledged west and named his farthest point victory point. *dun dun*

jcr and crozier developed a hand tremour after a fierce gale hit the ships during their final retreat from the antarctic.

returned from the antarctica expedition exhausted mentally and physically

in his late 40s, jcr was described by francis mcclintock as “a very quick, penetrating old bird, very mild in appearance and rather flowery in his style. he is handsome still…and has the most piercing black eyes.”

travelled and hauled approximately 500 miles in 39 days and was in the sick list for 2-3 weeks thereafter. jcr returned from the failed rescue attempt even more exhausted.

science acumen:

natural history

collected birds, mammals, marine life, and plants during his early expeditions. jcr shot down and stuffed a gull (ross’s gull - rodostethia rosea) and later on a penguin. he also discovered a new species of bird (white-billed diver).

provided the the zoological and natural history appendices for the 1824 and 1829 voyages.

assisted joseph hooker in collecting and laying out sea plant specimens for hooker to draw

had a plethora of animals/pets onboard the ships in the antarctica expedition, including goats, rabbits, chickens, and cats.

jcr himself was “an indefatigable collector of marine animals” that he intended to analyze and describe himself. jcr spent hours up to his knees in water and elsewhere dredging.

due to the stress of later years, jcr never got to analyze his collection. it was found as rubbish in his backyard after his death. the loss is considered to have held back oceanography for thirty years or so.

magnetic observations

was allowed to take lunar observations while he was still a midshipman, something that only the most experienced officers carried out

also tested the thickness of saltwater ice, recorded temperatures, checked longitudes, and went on land excursions

!!! located the north fricking magnetic pole !!! on 1st june 1831. he wrote a paper about it titled on the position of the north magnetic pole and read it to the royal society. the paper was eventually printed.

from 1835 to 39, together with edward sabine, jcr conducted the first systematic magnetic survey of great britain. he would also assist in the 1861 ordnance survey.

chaired a committee examining the accuracy of the magnetic compasses supplied to the navy

along with crozier, was lauded as the finest scientific navigators of the age. scholars say that by 1845, crozier was second only to jcr in seamanship and magnetic observations.

scientific involvement

served as “chief scientist” in the antarctic expedition. together with his captain’s duties, this was considered arduous work.

in kerguelen islands, jcr took personal charge of the observatories with crozier, living ashore, and going back to the ships on sundays for inspection and divine service.

was criticized by hooker for not encouraging scientific learning among his officers. jcr said that he and crozier were suitably qualified to handle tasks such as magnetic calculations, water samples and astronomical readings.

he just really wanted to *clenches fist* hoard all the science.

despite that, hooker did positively remark that jcr was uncommonly involved in the scientific activities of the expedition.

recognitions

was elected to many societies; including the linnaean society, royal society, royal astronomical society, and royal geographical society

received a medal from the royal geographical society and its counterpart in paris

received an honorary doctorate of common law from oxford university

finally published his book “a voyage of discovery and research in the southern and antarctic regions during the years 1839-43″ in 1847. the four years it took was a sign of jcr’s mental sluggishness.

although the expedition itself was groundbeaking, the book fell short, and it is of the scientific community’s opinion that jcr didn’t do himself justice.

was chair of the geographical section of the british association for the advancement of science. by god’s own hand probably, jcr was present when the association received a telegram on sept 1859 with the news of the discovery of the victory point note.

seamanship and other skill sets:

arts and languages

was often cast in the female roles in parry’s arctic theatre. 👀 he played corinna in the citizen, mrs. bruin in the mayor of garrett, poll in a musical entertainment called the north-west passage; or the voyage finished, and colonel tivy in bon ton; or high life above stairs.

contributed poetry to the north georgia gazette winter chronicle, a ship’s publication during the first parry expedition in 1819. one poem attributed to him was about the beauty of the aurora.

picked up enough of the inuit language from igloolik and was able to converse with the inuit they met in boothia

like many explorers, dabbled in art and painted sceneries from his voyages

hunting

shot a polar bear which made his crew very ill, either because of overeating or the bear’s poisonous liver

also shot a musk-ox at a range of 15 yards. it didn’t die and jcr had to shoot it again from five yards away. the moment is captured in one of john ross's sketches.

was given the chance to kill a 46ft whale, which his uncle found a distasteful sight. john ross didn’t mind the supply of blubber though.

led fishing expeditions and during one haul baited 3,378 salmon in a single net. he was really out there performing jesus miracles in the arctic.

sledging

readily picked up dog sledging from the inuit, with packs and equipment being pulled by a dog team of 12 while travelers walked. he ended up overworking the dogs and killing all but two of twelve. D:

in some of these sledge journeys, he was accompanied by thomas blanky.

he did pass on the rudiments of sledging to his protege mcclintock, who would perfect the technique and revolutionize british arctic sledging.

was able to sledge and chart peel sound and most of north somerset. he opined that franklin’s ships couldn’t have passed through peel sound because of the heavy ice. but that was exactly what they did.

seamanship

with jcr’s guidance and with the ships’ reinforced hulls, erebus and terror repeatedly rammed against pack ice so they could penetrate into the antarctic circle. they were the first ships to do so.

had an uncanny knack for spotting icebergs

spotted pack ice ahead of their ships and turned erebus away sharply, ramming directly to terror. the two ships were entangled then separated, with erebus's bowsprit, foretopmast, and other spars ripped away.

with the ship in bad condition, jcr executed a complicated manoeuvre to cross a narrow gap between icebergs. the move is like a car going in reverse, braking, and then drifting so the front swings right through an alley. the gap was “not twice the breadth of the ship”.

command:

charisma

was more popular than his uncle in the 1829 expedition, and often received the crew’s complaints

an officer in cove wrote of him: “the captain is, without exception, the finest officer i have met with, the most persevering indefatigable man you can imagine. he is perfectly idolized by everyone.”

quelled a mutiny twice in his career--first in 1829, then in 1836. in 1836, the cove seamen refused to sail after they were hit by a fierce storm, but were convinced when jcr addressed them in the quarterdeck.

had a sort of falling out with the falklands’ governor richard moody. hooker described it as: “they quarrelled most grievously, so that i was often unpleasantly situated.”

administration

was considered parry’s right-hand man though still a middie. as a lieutenant, jcr was was increasingly delegated scientific and other administrative duties that were meant for the captain.

left most of erebus and terror’s fitting out and recruitment to crozier while he finished with the 1839 magnetic survey.

wanted james fitzjames as his gunnery lieutenant for the antarctica expedition but was denied by the admiralty

just can’t do the damn grocery for some reason??? in hobart, van diemen’s land, crozier was “always starved” when it was jcr’s turn to purvey for the table, so crozier always had to eat his fill at franklin’s.

was prone to secrecy. the antarctic crew often had no idea where they were headed until they got there.

lashed out at his officers over minor issues following their second failed attempt at the south pole. robert mccormick wrote: “so strong were his prejudices, and... so difficult to reason with.” one wonders how he and crozier got on during this time.

while jcr did write to his superiors to report on the antarctica expedition, he did not publish a report in the papers. this would be a misstep as the expedition had lost public interest by the time they returned.

decision-making

like crozier, jcr didn’t trust steam engines and even gave it as a half-hearted reason for him to not command the 1845 expedition.

during the franklin expedition, crozier missed jcr’s captainship and expertise. he wrote of his misgivings and said: “james, i wish you were here, i would then have no doubt as to our pursuing the proper course.”

while the enterprise and investigator were stuck in port leopold, jcr ordered that foxes be trapped and fitted with collars carrying details of the relief expedition. they were entirely in the wrong island ofc.

reputation:

in society

described by michael smith as “a charismatic, popular figure with a flair that made him one of the greatest polar explorers of all time--something that more than compensated for his streak of vanity (five portraits), arrogance and occasional sharp tongue... displayed a breezy self-assurance and a strong sense of destiny”.

described by fergus fleming as “politically astute and had the knack of making himself popular”.

was initiated as a freemason, possibly on the recommendation of felix booth

a play was staged in the shady part of hobart about jcr and crozier's first venture in the antarctic. they did not attend. the play was reviewed as “better written than acted”.

hobart liked to throw jcr and crozier parties. one in 1840 displayed flags with jcr and crozier’s heraldry, with mottos written by jane franklin.

jcr’s read: “that flag so nobly won, shall wave once more / waved by thy hand, on th’ antarctic shore”.

in return, jcr threw a huge fricking party with erebus and terror strapped together and used as dance hall and dinner area. the place was decked with mirrors, flowers, swords, and candles.

was bestowed the title of handsomest man in the navy by jane franklin. jcr remained close friends with jane and acted as her advisor following the disappearance of the franklin expedition.

became a kind of recluse in 1844, writing: “my extreme abhorrence of public dinners, of which i have seen so much, has occasioned me to entirely give up attending them”.

became more of a recluse (an alcoholic recluse, sound familiar?) when his wife died

self-worth

in his expeditions to furthest north and south, jcr carried a little red book from his sister titled the economy of human life.

was the typical entitled british explorer afaict. jcr’s reaction to france and america pursuing antarctica can be summed up as: “how dare they? antarctica belongs to britain”.

when jcr received a well-meaning letter from charles wilkes enclosed with a map of the antarctic coastline he managed to chart, jcr decidedly didn’t take the route that his rivals had taken.

later on, he would reply to wilkes and tell him that the chain of mountains he named wilkes land was a mirage and did not exist. jcr is that petty bastard and he wants you to know it.

wilkes land did absolutely exist though, just not in the precise location that wilkes charted it. what did not exist--the mountains beyond the ross ice shelf that jcr named parry mountains. he was not beyond error.

tried to plant the union jack flag on a flat site in possession island, which turned out to be a massive bed of penguin guano. jcr is said to have sworn a blue streak.

cursed roundly at his publisher when he asked why jcr’s book was so delayed and that he would have to sell at a sale-or-return arrangement

influence

recommended john franklin as the commander of the 1845 expedition, but only after crozier told him that he felt he wouldn’t be up to it. several polar veterans tried to sway jcr but he stuck to his recommendation.

was generally optimistic even when the the franklin expedition hadn’t been heard of for almost two years. his opinion was highly valued may well have influenced the admiralty’s decision to stall a rescue effort.

disagreed with richard king’s recommendation to send a small party to back’s fish river since the small party wouldn’t be able to support 100+ survivors. we now know the survivors did make for the river.

was publicly criticised by king and his uncle on his management of the 1848 franklin search. historians are divided on this.

encouraged mcclintock to accept jane franklin's offer for him to lead the fox expedition. the fox expedition would end up finding the victory point note.

personal life:

courting and marriage

met his future wife while visiting isabella and her husband. ann coulman’s parents did not approve of jcr because of their age difference (16 yrs), jcr’s profession, and jcr’s “very uncertain and hazardous views”.

jcr was undeterred and wrote to a friend that “if ann can love me sufficiently to cheer with her smile the hour of difficulty tho’ a host were to rise up against us, in the name of cupid we would destroy them.”

docked a boat opposite ann’s house and met her in secret. the stuff of novels, i tell you.

brought scientific instruments to ann’s house and taught her how to measure terrestrial magnetism

supposedly rebuffed sophia cracroft’s advances in hobart. at this time, he was already engaged to ann.

named geographical features in antarctica after his fiance (cape ann) and his future father-in-law (coulman island)

settling down

with crozier as his best man, jcr married ann shortly after he returned from antarctica in 1843, and then promised to retire from active service. they settled in eliot place, blackheath, london.

crozier stayed with them in blackheath before he left for the franklin expedition in 1845. he described blackheath as “comfortless” and “scorching” and was very glad that the rosses moved to the country.

retreated to a country estate in buckinghamshire in 1845

jcr welcomed his first child james in the autumn of 1844, his second child ann in 1846, third child thomas in 1850, and last child andrew in 1854

the rosses’ married life were described as “a more perfect state of married felicity could not be imagined…if ever an observer could affirm there were two human sympathies concentrated in one, it might have been affirmed of sir james and lady ross....”

duty calls

was offered a baronetcy, a pension, and a year’s postponement if he would agree to lead the 1845 expedition. he turned it down to honour his promise to never sail again.

he probably also turned it down because he hadn’t recovered from four years in the antarctic and had taken to drinking to cope. the drinking probably hastened his death.

athough jcr had promised that he would no longer sail, ann gave jcr her blessing to lead a rescue attempt in 1848 and find their “dear frank”. in! this! house! crozier! was! loved!!

last years

ann died in jan 1857 of pneumonia, and jcr would never recover from the loss.

after his wife’s death, jcr rewrote his will and named edward bird and charles beverley as executors to look after the children. jcr knew bird since 1821 and beverley since 1818. bird, jcr, and crozier were middies together in 1821. ToT

the will was never legally executed and jcr’s sister marion became guardian of his four children.

burned his papers before he died. this one haunts me... why did you do that, james? what did you not want found?

jcr died on 3rd april 1862 and was buried beside his wife. he was 61yo.

after the stress of antarctica, of the franklin searches and public criticism, of the deaths of parry, ann, and most likely crozier and franklin, friends said that jcr died of a broken heart.

strained relations:

testified in a panel that sabine had done more of the 1818 expedition’s magnetic readings than his uncle, calling into question his uncle’s competency, thereby cooling their relations

frequently fought with his uncle regarding the running of the 1829 expedition. one of their arguments was likened by william light/robert huish to lavas bursting from a volcano. take with a grain of salt.

jostled with his uncle for recognition for locating the north magnetic pole and commanding the expedition. the whole affair was m e s s y and the admiralty opted to let it alone and let the family settle their own squabble.

hinted that he would not allow his uncle's account of the expedition to be published if his contribution to the book would be in any way altered (some places jcr named had been rennamed, removed, or added to).

supposedly placed a public advertisement telling the public that the appendix of his uncle’s book was written by jcr but he was not being paid for it

claimed that he was even offered money to publish his own account of the expedition but refused as he didn’t want to interfere with his uncle’s intentions

was accused by his uncle of giving up too soon in 1848 and using the franklin search as a pretense to find the passage. historians have defended jcr as his crew was hit with an early onset of “debility”.

scientists would later theorize that this debility was lead poisoning. six men died during jcr’s 15-month voyage. by contrast, he only lost three men in the four years he sailed with crozier to antarctica.

while their relationship was not entirely strained, jcr’s father george ross is an enterprising character, and would probably be a cause for embarrassment. george ross applied for bankruptcy thrice in his life.

george ross was secretary of the committe to collect donations for the 1829 expedition’s rescue. george back was to attempt an overland rescue, and george ross proposed himself to lead an attempt by sea. he had no sea experience whatsoever.

bestest friend in the whole wide world:

parry days

in 1821, jcr met and became firm friends with francis rawdon moira crozier and their friendship would last the rest of (one of) their lives. jcr was one of the few people who were allowed to call crozier “frank”.

when jcr married, this privilege extended to his wife. crozier often inquired after ann in his letters away, calling her “kind dear ‘thot’”.

franklin describes them as “it is truly interesting seeing them together. the same spirit animates each.” jcr and crozier were also described as “like brothers, so attached by their mutual tastes and dangers shared together.”

found several notes from crozier in supply caches in 1827. one of these charmingly read: “i cannot explain the mingled sensations i experienced the day i parted with you at walden isle. i did not think i was so soft...god bless you my boy and send you all back safe and sound by the appointed time is the constant prayer of your old messmate.”

another note read: “we think of you sometimes, always at dinner time. how much we would give just to know whereabouts you are....”

golden years

jcr’s first command was a rescue effort to save 11 whalers trapped in the arctic circle. many arctic veterans volunteered, but he enlisted crozier as his second in cove.

cove was supposed to be escorted by two bomb class ships in case they overwintered, but plans changed and they were not sent out. the ships were jcr and crozier’s future ships--hms erebus and hms terror.

although he declined the first offer of knighthood, jcr urged for his homie’s promotion to commander. he wrote: “the zealous and efficient manner in which he has fulfilled his trying and difficult duties makes me anxious that an officer of such high reputation and who has given so many instances of distinguished merit should receive that promotion which it has been the invariable practice of the admiralty to bestow...”

endearingly referred to in hobart as “the two captains”. eleanor franklin wrote of them as “very nice people”. bless

at the hobart temporary headquarters, jcr strung his sleeping hammock right next to crozier’s (ToT)

became “comically serious and meditative” when he thought that crozier was considering leaving the antarctic expedition and staying in hobart.

named a headland in ross island as cape crozier.

celebrated new year’s day of 1842 by throwing a party in an improvised ballroom in a nearby iceberg. a throne was chiselled from the ice for jcr and crozier.

“captain crozier and miss ross” sang and danced a quadrille, and when they made their way back to the ships, they were pelted with snowballs by the crew.

it’s all downhill from here

after antarctica, a depressed crozier left london without saying farewell to jcr and ann. he wrote to them while in france: “it has caused me much pain, but the truth is i could not make up my mind to visit london now.”

recommended crozier or edward bird as franklin’s second. when the admiralty asked for his opinion on crozier’s fitness, jcr eagerly supported his friend’s appointment.

crozier reaaaallly missed jcr while he was out on the franklin expedition. in his last letter to jcr ever, crozier wrote: “how i do miss you. i cannot bear going on board erebus. sir john is very kind and would have me dining there every day if i would go... all goes smoothly but, james dear, i am sadly alone, not a soul have i in either ship that i can go and talk to... i am sadly lonely & when i look back to the last voyage i can see the cause and therefore no prospect of having a more joyous feeling.”

while the rescue ships were being fitted, jcr sent an advanced note to crozier via hms plover. he wrote: “we are settled very quietly in the country and it will be a great happiness to us to see you again at our fireside... the command of the expedition is to be in my hands & with old bird as my second i feel satisfied that we shall not be found wanting....”

ann ross also sent a note, displaying the friendship that developed in their brief acquaintance. both letters were returned undelivered.

legacy:

jcr’s coat of arms includes a dipping needle pointing north and the union jack flag flying above it with the date 1st june 1831. his heraldry also includes a fox’s head.

when the entirety of the antarctic expedition’s validated findings were finally published in 1868, six years after jcr’s death, there was little public fanfare, but it’s worth was well-known in the scientific community.

some errors in jcr’s scientific recordings were eventually found, but scientists say that considering his basic, sometimes faulty, equipment, it was a wonder he didn’t have more.

other wildlife named after jcr are flowers, a seal, and a squid.

helped esther blanky and ann reid get their widow’s pensions by testifying that ice masters were indispensable in expeditions. blanky and reid were not technically in the navy. jcr said that not granting the pensions would be “an act of injustice”.

hooker remembers jcr as “really the greatest by far of all our scientific navigators, both in point of length of service and span of the globe. justice has never been done to him.”

robert falcon scott said about jcr’s antarctic achievements: “it might be said that it was james cook who defined the antarctic region, and james ross who discovered it.”

and there it is!!! sir james clark ross is undoubtedly brilliant--even his uncle can’t contest that--but he is also far from perfect. he was a complicated man and certainly had his share of mistakes and character failings. of his grave mistakes, i can say that they were born out of lack of information, and none at all of malice or ambition like many of his contemporaries.

-- -- -- -- --

this is messy and is all in good fun so if there are any mistakes, please let me know. if you want specifics for a certain thing hmu, but i can’t promise i’ll remember the source for all of them.

in general though, i got these from: fergus fleming, michael smith, m.j. ross, owen beattie & john geiger, and of course from several posts and links provided by @tttack @indifferent-century @ltwilliammowett @handfuloftime @skazka @hangingfire

405 notes

·

View notes

Photo

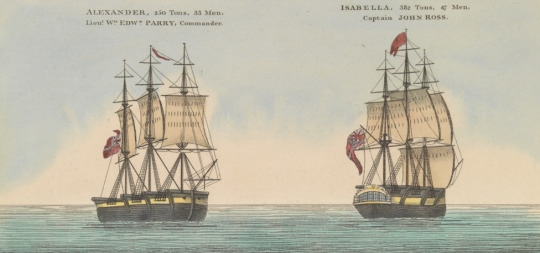

James Clark Ross’s ships

HMS Isabella (midshipman, 1818), HMS Hecla (midshipman, 1819-20; lieutenant, 1827), HMS Fury (midshipman, 1821-23; lieutenant, 1824-25), Victory (second-in-command, 1829-32), HMS Victory (supernumerary commander, 1833-34), HMS Erebus (captain, 1839-43), HMS Enterprise (captain, 1848-49)

Not pictured: HMS Briseis (first-class volunteer, midshipman, 1812-14), HMS Acteon (midshipman, 1814-15), HMS Driver (midshipman, 1815-17), HMS Cove (captain, 1835-36)

Artist information and a few notes below:

I wasn’t able to find images of Briseis, Acteon, Driver, or Cove. Though the ship plans for Driver are here and here if anyone’s interested.

Although Ross’s name was on HMS Victory’s books from 1833-34 to give him the necessary service time to be promoted to post-captain, he was on leave the entire time to assist with his uncle’s narrative of the 1829-33 Victory expedition.

Images:

James Whittle and Richard Holmes Laurie. Portrait of the Vessels on the Polar Exploration of 1818. 1818. Colored etching. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Detail. (x)

George Lyon. “The Last Appearance of the Sun for 42 Days”, in The Private Journal of Captain G.F. Lyon of HMS Hecla During the Recent Voyage of Discovery Under Captain Parry. London: John Murray, 1824.

Henry Parkyns Hoppner. Situation of H.M. Ship Fury August 25th 1825. 1826. Tinted engraving. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. (x)

John Ross. “The Victory Under Sail for the Last Time”, in Narrative of a Second Journey in Search of a North-West Passage and of a Residence in the Arctic Regions During the Years 1829, 1830, 1831, 1832, 1833. London: A.W. Webster, 1835.

Edward William Cooke, H.M.S. Victory First Rate 104 Guns. Portsmouth Harbour. The Flagship of the Late Lord Nelson. On board of which he was killed off Trafalgar Oct 21st 1805. c. 1828-30. Colored etching. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. (x)

Richard Brydges Beechey, HMS ‘Erebus’ Passing Through the Chain of Bergs, 1842. 1860. Oil on canvas. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. (x)

W.H. Brown. The Devil’s Thumb, Ships Boring and Warping in the Pack. 1850. (x)

Sources:

O’Byrne, William Richard. A Naval Biographical Dictionary. London: John Murray, 1849.

House of Commons. “Report from Select Committee on the Expedition to the Arctic Seas”. London: s.n., 1834.

Ross, M.J. Polar Pioneers: John Ross and James Clark Ross. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994.

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

HMS Hecla in Baffin Bay, illustration from Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a Northwest Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific Performed in the Years, 1819-20 in His Majesty’s Ships Hecla and Griper, by Lieutenant Frederick William Beechey ( 1796-1856)

#naval art#hms hecla#beechey#captsin parry's first arctic expedition#looking for the northwest passage#1819-20#age of sail

91 notes

·

View notes

Photo

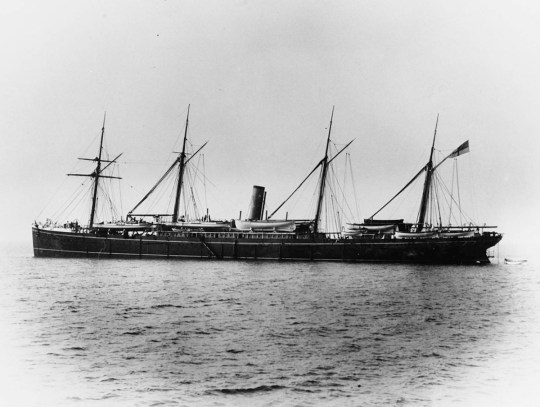

Book Review. The Royal Navy Wasp: An Operational & Retirement History

So, I have another book from those fantastic people over at Pen & Sword Books to have a look at, this time it’s a subject matter with wings that are rotary rather than my usual fixed wing interest.

This publication looks at the small but mighty Westland Wasp, this was the first helicopter in the world to be designed to be deployed at sea.

The book begins by looking at the conditions during the post war period that lead to the development of the Wasp as a solution. Anti-Submarine operations using aircraft were nothing new, in fact aircraft have been used since the first world war to attack submarines, albeit in a much less sophisticated manner. During WWII though things were advancing rapidly but still ships and aircraft alike needed to catch their prey on the surface to launch an attack.

Technology continued to advance and by the 50s aircraft were able to detect even submerged vessels. It was at this point the Navy decided the use of a small helicopter that could be launched from destroyers and frigates as a weapon carrier in anti-submarine warfare operations could be an effective tool.

From the outset the book includes anecdotes from pilots and crew. From the test pilots, to those that were to use the aircraft in operations and finally those that went on to operate the aircraft in a civilian role. These are taken not only directly from the crew members or official reports, but also from articles in publications such as Cockpit! or Flight Deck Magazines for example. I found many of these to be really fascinating and I loved being able to read these first-hand accounts of what the aircraft was like to operate and the tasks it was asked to carry out.

Moving on we take a brief look at the company that would eventually go on to secure the contract for providing this ship-based aircraft, The Westland Aircraft Works, and how it came to purchase Saunders Roe and with it their prototype project P531. This aircraft was subsequently developed into the land-based Scout and what was briefly named the Sea Scout, which was the basis of what became the Wasp

The development of the Wasp during the early years is looked at, covering everything from engine improvements to safety systems such as the flotation devices for a ditched helicopter. Weaponry and aircraft roles are looked at next including the development of new roles for the Wasp to be utilised in as a counter to emerging threats such as the advent of the Fast Patrol Boat for example.

As the book continues we hear about the initial deployment of the aircraft to the vessels it was to serve from and the trials that those early crews faced, both the flight team and the ships company. More articles from Flight Deck and Cockpit provide a great insight to what these early days of Wasp operation was like.

There are more anecdotal articles describing first-hand what it was like to work with the aircraft including a brief diary covering a year of operations by a Naval Air Engineering Mechanic on board the HMS Naiad during the early 80s. There are also accounts from three different vessels carrying Wasps that were deployed during the ‘Cod Wars’ of the 70s. This makes for interesting reading due to the unusual and sensitive nature of the situation.

Returning to the 80s we head into the Falklands conflict, looking at the aircrafts first real operations in a theatre of war. This section begins with the account of the flight on HMS Endurance which was the only Navy vessel in the area when hostilities began, and it is during this account that we hear about the encounter between the Argentine submarine Santa Fe and the Wasp that saw the first guided missile ever fired by the Royal Navy not only being fired but also meeting its target.

Falklands missions are also described from Flights aboard several other vessels including HMS Plymouth, HMS Yarmouth, the hospital ship HMS Hydra along with HMS Herald and HMS Hecla. Missions after the surrender are also looked at from other vessels.

There are then more personal accounts from crews that flew the aircraft during its service with the Navy, including the book authors own experiences with the aircraft.

Moving away from the Wasps service to the UK the book takes a look at their 2nd lease of life which was to be found abroad. Service was to be seen with New Zealand, The Netherlands, Indonesia, Malaysia, Brazil and South Africa with some aircraft remaining in service well into the 90s and beyond, impressive considering the type first flew in 1962.

Finally, the book looks at the few Wasps that are still active although not in military service. With the aircraft now in civilian hands the trials and tribulations they have faced since becoming civilian owned are covered, such as an impromptu search and rescue mission during a 2016 air show after another aircraft was forced to ditch into the sea.

In conclusion, I have found this book to be a very interesting read. I found the stories from operations to be very compelling and those centred around operations in the Falklands in particular were my favourite part of the book. Whilst it is true that this is an aviation history book more than anything else there are still some great reference images for modellers alongside the fantastic stories and I don’t think the level of detail the book goes into should be off-putting to anyone with an interest in military, naval or aviation subjects.

If you fancy picking up your own copy of this title then you can do so over at Pen & Swords Website, I would also recommend having a good look around on the site too as there are loads of great titles to be found.

#kitsandbits books#kitsandbits bookswasp#book review#books#book#books for modellers#books for model makers#books for scale modellers#scale modelling reference material#reference material#reference books#modelling reference#history#aviation#helicopter#naval#navy#royal navy#wasp#rotory wing

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

hc: rns terror. The RNS Terror was originally the historic HMS Sulphur, a Hecla-class bomb vessel of the British Royal Navy whose construction was completed on February of 1826. She was small at approximately 105ft in length and 372 tons, could hold up to a 65-man crew, had a sluggish top speed of about five knots, and without any steam engine, was fully-rigged with three massive masts, her sails like sheets of clouds billowing over the seas. With two 6-pounder cannons, ten 24-pounder carronades, one 10-inch mortar, and one 13-inch mortar spread over, she may have been no warship behemoth, but if push came to shove? She was ready to open fire.

Unfortunately, though, Sulphur was decommissioned. Broken apart in 1857. For the purpose of this story, however, she survived and was later converted into a museum, docked, intentionally forever, in the HMNB Portsmouth.

But she wasn't to stay forever.

After the bloody Resource Wars and, eventually, the detonation of the bombs, many of the functioning warships were lost, most decimated by naval battle or never to be seen again when the nukes fell. The majority of the relics of ships stayed, though. Sulphur, included. Post-war Portsmouth reinstated her, refitted her, and somewhere between 2077 to 2260, she was back patrolling the English strait from looters, invaders, and pirates; protecting home and country; fishing for much needed food; and raining hell on her enemies. Yet, she was not the same old Sulphur.

When she was converted to a museum, her armaments were swapped out due to safety regulations. Today, she is again armed to the teeth with almost double the mortars, guns, and cannonades, and even improved with a built-in steam engine that allows her to sail at nine knots, some dish and radios for communication, and now --- the Holy Grail, perhaps --- a “state-of-the-art” (by English standards since they did not harness nuclear power and fission the way America did) laser cannon. Sure, she may be no USS Constitution with her unfathomable football-field-sized rockets, but she isn’t the same sailing-turned-survey ship from the 1800s. In 2283, when the mission to sail for America was declared, she was officially renamed to Terror --- a nod to the lost crew of the Franklin Expedition, and a promise to bring success and honor back to the name.

Andrew Alexander Corrigan was to be her captain. And the second Age of Sail, of sorts, had begun.

OUTSIDE

Now, to the pictures! I’m starting off with the outside view:

Three masts

Dark/black finish

This is a model kit, but visually and historically accurate. Check it out here!

Below is the Terror from a quarterdeck view. Note the ship’s wheel.

Here is the stern, or back, of the ship with a screenshot from the AMC series. All Hecla-class bomb vessels shared this similar look. Of course, instead of Erebus, we would see Terror.

I should also mention the Terror is not as massive as one might think --- not like today’s cruise ships or anything. I only use words like “massive” because it may seem large to a man, but in comparison to others, it isn’t. The two pictures below, one of the stern (back) and bow (front), can give you a frame of reference as to the size of the ship versus a grown person.

INSIDE

Below the upper deck (outside), we have the lower deck, the orlop deck, and hold. The captain’s quarters is where the windows above are, so the lower deck. Men usually sleep on the lower deck as well. Sickbay is located at the orlop, as well as mess hall, and the hold is where the steam engine, coal, and stores are located.

The captain’s quarters.

In Corrigan’s quarters, the table is set off to the left side and strung by ropes to prevent sliding.

The captain’s berth. Small. This small room is almost cupboard-sized and, naturally, attached to the captain's quarters, sectioned off by a sliding door.

Non-commissioned officers sleep in hammocks such as these. This is from the HMS Victory. The space is much larger than Terror’s, which is a much smaller ship.

The wardroom, below, is where commissioned officers gather to dine. I wish I had a photo of just the set, but this will suffice. It’s a cramped area and could squeeze up to nine at the table with two, usually the captains’ stewards, standing to the side.

Sickbay. Many vials and medicine are stored in cabinets or on shelves. With rough sailing, these could easily knock over. Other cots and hammocks are here, too, to accomodate more than one ill seaman.

Credit: Many photos were taken here and screencapped from the series

Hope this proves helpful for some of you who haven’t seen the show! I chose the Hecla HMS Sulphur because it was the same class as the HMS Erebus, which shares a lot of visual similarities with the HMS Terror, and thus, Corrigan’s Terror. As evident from this entire blog, I tried to emulate The Terror as much as I could with elements from history. :^)

#( corragain: hc )#[it occurred to me you guys might not know what the terror looks like? so here's my guide!#scroll to the bottom for visuals. the top portion paragraphs explain more of her history and armaments for the postwar age.]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

for the source on the shipboard newsletters, may i introduce:

The North Georgia Gazette and Winter Chronicle of the HMS Hecla (1819-20)

and the

The Illustrated Arctic News of the HMS Resolute (1852)

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Pacha of Many Tales

I’m finally finished with The Pacha of Many Tales, and it was… something, I suppose. It certainly dethrones The Pirate as my least favorite Marryat novel to date. I think The Pirate suffered in my estimation since it was only the second Marryat book I had read, and right after Mr. Midshipman Easy at that. After such a clever and humorous story it felt boring and bombastic, and one of these days I ought to give it another chance.

Reading The Pacha of Many Tales just once was more than enough, I’m sure of it. It is sometimes described as a “parody” of Arabian Nights, but it only borrows a similar framing device of a bored and fickle ruler (the Pacha) who demands entertainment with stories from his subjects. The Pacha and his vizier will eavesdrop on the common folk, and when they overhear an exceptionally colorful or inscrutable remark they insist on the story behind it. Certain characters return for multiple tales and others make a single appearance.

It is a great deal of orientalist nonsense, needless to say, although Marryat seems to be drawing from sincere translations for a lot of the material. There are at least two academic papers referencing Pacha that I came across in the course of looking up things from the book, and it is possibly of interest to people looking for Western, specifically British depictions of “exotic” cultures in the Middle East and the Mediterranean region. Marryat’s writing in general is heavy on broad stereotypes, often offensive stereotypes, but at least it has the redeeming qualities of being original and authentic in its Age of Sail content, and entertaining. Not so with the 500 pages of dreck I just plowed through.

Another note on the offensive stereotypes: it’s true that Islamic customs and religious officiants appear backward, primitive, and superstitious in Pacha; but Marryat’s treatment of European Catholics is just as patronizing. They are shown as equally regressive and corrupt, and this practically gets lampshaded by an English sailor who observes to the pacha and his vizier, “Jack Soames said that you warn’t Christians, but that if you were, you could only be Catholics.”

Marryat refrains from editorializing or interrupting his story, which was originally serialized in his Metropolitan Magazine between 1831 and 1835. There’s only one brief moment in the opening pages when Marryat speaks in his own voice, seeming to refer to his guilt and trauma stemming from his long military career. It’s a sad, disquieting passage, following a meditation on the “bloody hand” of heraldic symbolism:

And I, whose memory stepping from one legal murder to another, can walk dry-footed over the broad space of five-and-twenty years of time, —but the “damned spots” won’t come out— so I’ll put my hands in my pockets and walk on.

Conscience, fortunately or unfortunately, I can hardly tell which, permits us to form political and religious creeds, most suited to disguise or palliate our sins.

(Just in case you forgot Frederick Marryat had PTSD, owch.)

The best tales are those of Huckaback, a renegade French sailor of shifting national and religious allegiances. Marryat is in his element with the sea-stories, and we get a more concrete idea of the time period from Huckaback’s references to historical events such as la Terreur of 1793. (The other characters almost exist outside of history.) At one point Huckaback purchases a whaling ship and heads for Baffin’s Bay, and I was very curious to see an 1830s pop culture representation of an arctic voyage. It ends up with the ship beset and trapped in ice, the crew succumbs to scurvy and eventually resorts to cannibalism. (Prescient!)

Despite this negative experience, Huckaback returns for a second adventure in the arctic. This one is more mystical and fantastical, with Huckaback trapped inside an iceberg in a state of suspended animation before he’s rescued by the inhabitants of a floating island. Amidst this weirdness the real-life Captain William Parry makes a cameo, presumably with HMS Hecla and Griper in 1819-1820. As Parry’s men cut through the ice to free their ships the saws narrowly miss Huckaback in his icy prison.

I am beyond mystified that Pacha gets a higher average review on Goodreads (4.08 stars) than the superior Frank Mildmay (3.7 stars) or The King’s Own (3.45 stars). Both of those books have their flaws, but when they’re good they’re really, really good. Pacha might have a more consistent structure and theme, but it never rises to the level of truly great storytelling. It’s creaky and racist by modern standards, and you can skip it without missing much.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#the pacha of many tales#the pirate wasn't funny and had just too much purple prose#i know why ppl are mad at the king's own but it is very underappreciated#who is giving 4 stars to this crap turn on your location i just want to talk#book review

1 note

·

View note