#i am the flavor of dumb bitch who cant get goncharov out of my head so I translated quotes into my conlang

Text

so I made a language

well technically i've made kind of a bunch of languages

and probably already have a very old post about one of them

but here's another one. I call it Pinõcyz. I started working on it in February of 2020.

PHONOLOGY

I don't want to get too deep into the evolution I did on this, but to illustrate a little of that, I'll explain what's going on with the vowels and /z/. Basically, in most consonants where the modern language lacks a labialized pairing, i.e. /m l q/ and others, the labialized consonant simply unrounded. Historical /ðʷ/, though, merged with /z/ instead, yielding contrasting /z zʷ/ preceding /ɛ ɵ u ɔ/ and contrasting /ɛ ɵ u ɔ/ and /e ɨ ɯ o/ following plain /z/.

I realize also that I've sort of doubled the explanation of this in the notes maybe?! and left a note about the romanization in this screenshot that I deleted the romanization from because I want to display it separately. I'm not going to replace this screenshot a fifth damn time. :D

ORTHOGRAPHY

The Pinõcyz language is written primarily with the Tewrinnal /teɣrinːal/ script. It's an abugida.

...For a language with eleven vowels and fairly complex syllables.

You know, very much not the normal simple, open syllables that such a system usually operate best with.

So just what the hell is going on here?

Well, every character has an inherent vowel /ə/. To represent other vowels, diacritics are used, and to represent, for example, a single-consonant coda, another diacritic is used to mark that there isn't a vowel. For example:

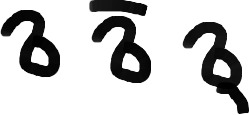

/mə me m/

There are six regular vowel diacritics:

/nɨ ni no na ne nɯ/

But, we also have to handle four more vowels somehow, and the labialized consonants where they're distinct.

That's all handled with one diacritic, marking both for labialization on the consonant and, where relevant, these different vowels.

/nʷɵ nʷi nʷo nʷɔ nʷɛ nʷu/

So that helps with those things. But what happens with a consonant cluster, or a geminate? Those are weird, right?

Well, the script uses a longer diacritic for that. Let's use the name of the script as an example:

/teɣrinːal/ (It's written from right to left.)

So, couple of things going on here. First, that second chunk is /ɣri/. The glyph for /ɣ/ doesn't need the null vowel diacritic (shown here on final /l/) because it's marked with this tie bar that shows it's part of a cluster in the same syllable as /ri/. And second, that third chunk is /nːa/. Marking geminates via this tie bar is one of several uses of this other glyph, the null-consonant.

We also have to handle initial vowels.

And diphthongs.

So what's going on here?

/ə ɨ i o a e ɯ/

Here's the null-consonant glyph, and every vowel on it. These don't take the rounding diacritic; for geminates, said diacritic will appear on the consonant glyph proper.

/qaj teu/

Diphthongs are written as though the first component forms a simple syllable with the consonant, but then with the null consonant immediately following.

Alright.

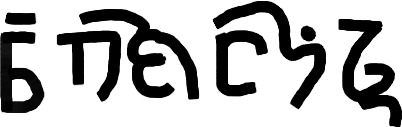

So here's all the base glyphs real fast:

/∅ m n ŋ p b t d k g q/

/t͡s d͡z t͡ʃ d͡ʒ r l j f v s z/

/ʃ ʒ x ɣ h ð ɬ/

And one last quick note, /zʷ/ is represented by the glyph for /ð/ with rounding diacritic. Here's an example, in the form of a common given name:

/zʷɛzi/

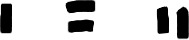

Last but not least, the script has a couple of punctuation marks:

In order, something between the role of a comma and a semicolon; a marker for the end of a sentence; and an exclamation and imperative marker. These are small and appear next to the bottom of the last glyph, much like a period or comma might.

I don't have a font of this yet, and even if I did I'd have some trouble getting that to function well on Tumblr. So I'm going to briefly explain the romanization that I tend to use.

For the non-labialized consonants I have:

/m n ŋ p b t d k g q t͡s d͡z t͡ʃ d͡ʒ f v ð s z ɬ ʃ ʒ x ɣ h r l j/

⟨m n ň p b t d k g q c ż č ǧ f v ð s z ł š ž x w h r l j⟩

For the vowels I have:

/i ɨ ɯ e ə o a/

⟨i y u e õ o a⟩

The other four vowels and the labialized consonants are handled with diacritics on the characters for the vowels. So,

/ɛ ɵ u ɔ/

⟨ê ŷ û â⟩

and to mark that the preceding consonant is labialized, i and o also take circumflex, î and ô. The result is that ⟨w⟩ represents both /w/ and /ɣ/, and ⟨j⟩ represents both /j/ and /ɥ/, and obviously, for example k, g, r represent both plain /k g r/ and labial /kʷ gʷ rʷ/, and so on.

And because this doesn't handle labialized z, I have /zʷ/ ⟨ź⟩, and for example ⟨zê⟩ /zɛ/.

This probably isn't anything close to an ideal system, but it's what I settled on in 2020 and I don't think I want to change it. It's weird, but it's phonetic, in a sort of weird roundabout way.

So let's get into the grammar.

We'll start relatively simple: word order is verb-subject-object, with descriptors that follow what they're marking except for some in the animate class that are derived from verbs (more on all that later), and placement of other things like indirect objects and relative clauses varies in a couple of ways.

Also, subject pronouns often, but are not required to, drop entirely.

NOUNS

Whether a noun is considered animate or inanimate has some impact on case markings and other things like that. In general, people, certain concepts, feelings, anything divine, weather phenomena, time, animals, some tools, injuries or illnesses, fire and water, and plants food items considered spiritually important such as tea and many herbs are animate; other nouns are inanimate. Certain shelled sea creatures are also inanimate.

Case markings carry a plural marker and information related to definiteness within them. Animate nouns are considered definite by default and so have an indefinite article that incorporates into the cases; inanimate nouns are considered indefinite by default and so incorporate a definite article into their case markings.

Pinõcyz has split-ergative alignment based on animacy. Animate nouns take the (unmarked) nominative case as subject and the accusative case as object; inanimate nouns take the ergative case as subject and the (unmarked) absolutive as object. All the case markers except the ergative appear as suffixes; the ergative, though, is a particle that precedes the noun. There's a lot of wonky historical reasons for that, a bit beyond the scope of this.

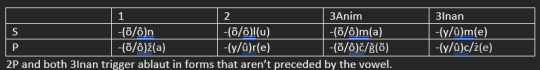

Here's a table of the regular forms:

Where I have something in parenthesis, what sounds occur at the end of a noun determine whether it's present. For the vowels (i.e. most of them), it drops if the noun has a final vowel, and for the definite singular inanimate dative, that l is present if it's a final vowel and gone if there's a final consonant. There are other effects that the final consonant can have but they're often less predictable than this.

I'll explain the ablaut more when I get to verbs since it's more relevant there, but the definite singular inanimate dative does trigger ablaut, and the inanimate singular definite genitive triggers ablaut in nouns with a final vowel, where the y is dropped.

POSSESSIVE CONSTRUCTIONS

The possessor is marked with the genitive case and precedes what it marks. Examples: Tuštez bylen "Tušte's cousin", ðandaz manõn "rapids", lit. "river's teeth"

ADJECTIVES

Here I'm using "adjectives" as a sort of catch-all term, there's not a separate class of adverbs. There are, however, separate sets of animate and inanimate descriptors. These come in the form of a few adjectives that can simply be used for either sort of noun, i.e. izy "also", or in the form of separate, often derived forms for animate nouns, i.e. ðakan rõr "the stone nearby", but šõrõr celiż "the nearby ash tree". Many animate adjectives are derived more recently from verbs, and those ones precede what they describe, unlike the others. The new verb-derived animate adjectives are still often transparently related to one of several verbs. For example, šõrõr here has incorporated šõ "to have" as a prefix; wâðrata "dry" takes wâð "to be" as a prefix, and so on.

Except for a few exceptions, animate adjectives may not be used for inanimate nouns and vice versa, i.e. šõrõr ðakan here would be ungrammatical.

ABLAUT

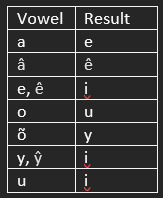

I'm going to take a second before I get into the rest of this to discuss ablaut in more detail.

Sometimes, but not always, an i or e vowel remains in a suffix that triggers ablaut. This was universal before some of the vowels were eroded, but is now a bit trickier to predict if the vowel has been lost. Historically (read: before vowel length was lost, a bunch of final vowels got eroded, and a bunch of other things happened), a long i or e in the final syllable triggered fronting and raising of the vowel in the preceding syllable. How that expresses in the modern language is roughly reflected by this table:

Most of the time, labialization was retained through this raising, so sê "to float" > sîż "they (inanimate, plural) float".

Some verb endings including tense markers and subject agreement trigger ablaut.

VERBS

Oh boy these get messy. Alright, I'll start with the tenses. I'll give an example sentence or two with each, and I'll explain the personal agreement after that.

Simple Present: unmarked. Deals in ongoing actions, states, things like that. Example: Symvinan "I'm thinking".

Habitual: -čin if the noun has a final consonant; -ǧin for a final vowel; in final plosives, the č metathesizes into the word like CVčCin. Triggers ablaut. Deals in actions that the subject carries out often or habitually. Examples: Łezeǧinõn manõnxaz "I often swim in the river"; Wêličkinõm dõz ðažgaňna "She often moves my pans".

Imperative: -žǧin for final vowel, -ščin basically otherwise; rarely -šõčin with final clusters. Triggers ablaut. Commands, things like that. Example: Biliqščin żŷknõ! "Prepare the boat!" (Fun note: żŷk "boat" is an animate noun; that's the accusative case.)

Future: -ðem, VðCem metathesis with final plosives. Deals in things that will take place in the future. Triggers ablaut. Examples: Bigimðemõǧ yquddiz bêdêkkuinan "They will gather the king's council"; Taxe beðqemõl "Therefore you will flee".

Conditional: -sõn if final consonant, -zõn if final vowel, VsCõn metathesis for final plosive. Deals in possibilities, uncertainties, etc. Example: Boňgestõnõn żen Lagruisyn "I might mail those to Lagrui".

Subjunctive: -õð for some final consonants, -ôð for others; -ð for final vowel; metathesizes with final stop VðõC unless it's in a cluster. Expected, preferred, "ought to be". Example: Kalyðõl "You ought to sleep".

Past-habitual: -šał with final consonants, -žał with final vowels; metathesizes VšCał with final plosives. Things the subject used to often or habitually do. Example: Kyużêžałõn ðembawynxaiz "I used to explore among these ruins often."

Optative: -kî for final consonant, -gî for final vowel. Triggers ablaut. Deals in things desired or hoped for by the speaker. Example: Erõmjeqqîl nida "I hope you return early". (In this example the consonant was absorbed into the final q on the verb root.)

Pluperfect: -łyš, metathesizes VłCyš for final plosives. Final consonant in the suffix retains labialization when vowels follow. Deals with actions completed by a specified or implied time period. Example: Dîrzynłyšôč "They (animate, plural) had taken ill". (Final consonants in the root form will have lost labialization, but they retain it when, like here, a vowel is introduced via a suffix.)

Experiential: -šai for final consonant, -žai for final vowel, VšCai for final plosive. Marks an experience that has happened at least once without respect for time, and is repeatable. Example: Sylezunčaiž wâðger waišqalnan "We have survived some large floods". (This example shows fortition of the fricative immediately after a nasal, a common sound change.

Now let's look at the regular forms of the person endings.

Most often, these will retain the vowel before the suffix consonant, but that is not always the case, sometimes you lose it and keep the one after, and it's not predictable in a way I can describe neatly here. For final vowels in the root or the TAM affix, typically no vowel is retained after.

Here's where things get WILD.

PASSIVE VOICE

The passive voice renders the agent of an action as an oblique and promotes the patient, so that it's focused a bit more. The passive is derived from an auxiliary verb that takes the tenses and the verb agreement, giving a qir- prefix. Then the verb is incorporated after that, and then -(u)z prefix, where the u drops if the z is allowed to form a final cluster with the final consonant or the verb has a final vowel. Then the agent of the action takes the ablative case. Example:

Qiršõmrenõnżõ Madriz lezgammuðgõż "Madriz was stabbed by an impostor". (This sentence is sus. Also note the fortition, z > d͡z after that nasal.)

ANTIPASSIVE

In ergative constructions, it's often more appropriate to de-emphasize the agent. In these cases, an antipassive construction forms, basically the passive construction but with the oblique-marked object in the allative case. This shows up mainly in relative clauses, but can form in fully independent sentences for emphasis reasons. Example:

Qiršymqamżõ pera Varasyn "An apple hit Vara"

An active-voice rendering of this same sentence would be Qamšym gõr pera Varanõ; the ergative particle here lends a degree of emphasis that is not always useful. Some speakers even consider it ungrammatical to form a sentence with the accusative on the object and the ergative on the subject, though that's far from universal and is mostly a hard-and-fast rule only in relatively conservative dialects. (For the most part, variation among dialects is beyond the scope of this post.)

MEDIOPASSIVE

The mediopassive construction handles both reflexives and certain intransitive sentences where the subject is not necessarily interpreted as the agent, such as "I fell". It derives from an old auxiliary verb ša- which takes any tenses and the subject agreement, but in this case the main verb, marked with the experiential, is not fused to the end of that. Examples:

Šan kadynčai "I fall" (fortition after the nasal again); Šamom dewšai "He has washed himself".

CAUSATIVES AND INDIRECT OBJECTS

A causative will usually take the form of the cause oblique-marked, taking the ablative case; an indirect object is typically marked with the dative case unless circumstances suggest something else. Typically, an animate oblique will precede the verb and an inanimate will follow the entire clause, but this is somewhat flexible for the purposes of emphasis. Examples: Taraðõd sybêkužõn Jŷddenõ "I met Jŷdde because of Tara" (causative); Kitronyz šŷllalõ leðõn żŷknõ "I'm building a boat for Kitron's clan" (indirect object).

NEGATION

Negating nouns and adjectives is done with a suffix -riq; this does not trigger ablaut. Example: cymanõnriq "nonexistence, void". In nouns this is primarily a derivational method.

In verbs, there is a negative auxiliary, jan in root form. It takes personal agreement, preceding the main verb, and the main verb takes tenses. Here's the forms of the negative auxiliary:

In passives, antipassives, and mediopassives, the negative auxiliary takes root form and precedes the verb construction as a particle.

Examples:

Jan šan kadynčai "I did not fall"; Ne vreita grõn teta "The candle isn't burning".

QUESTIONS

The interrogative terms are:

qa "who"; hud "what"; jõl "where"; tõr "when"; wal "why"; ðam "how"; gy "which one", also a general interrogative; jezyn "to where"; jeðõd "from where". They usually precede the verb, with the exception of gy when it precedes a noun, i.e. Jenin gy tynnanõ? "Which sumac tree am I looking for?"

RELATIVE CLAUSES

The interrogative terms also function as relative pronouns.

If the noun of the relative clause is animate:

Subjects, direct objects, and indirect objects can be relativized without any extra trouble, simply constructing the clause out of an interrogative and then the verb and relevant noun. Examples:

Subject- Kasran kêdynõ qa bašqõm "I see the dog who ran"

Object- Gy bûriðemõl ňaňlõ qa ðõkasran? "Will you wait for the man who I forgot?"

Indirect object- Wâðõm pinõ qa daxõn luz qarut "That is the person who I gave your money to"

For obliques, genitives, and objects of comparatives, it's necessary to use a passive. Examples:

Oblique- Jenižǧin sadynõ jeðõd qirmomrenõnżõ Nabi lezgammuðgõż! "Find the knife with which Nabi was stabbed by an impostor!"

Genitive- Gy činõl riżalnõ qaz qirõmjeniz rênnan Dargoðõd? "Do you know the shrub whose leaves are sought by Dargo?"

Object of comparative- Dalqamõn ainan jeðõd šoðõð qirčinõnfilz "I playfully hit the nonbinary person who I am sung better than by"

Yeah, Pinõcyz has a word for the act of hitting someone gently in a humorous or flirty way, it's dalqam.

If the noun of the relative clause is inanimate:

Only absolutives may be relativized. Example:

Absolutive- Qiršõngaduz wegrizxaiz jõl kerkożżynčõm verraw "I was given birth to in the city which the king declared war against".

For all other sorts of relative clauses, antipassives must be used. Examples:

Ergative- Vreitašõn ludan hud qiršõmfaisqõ Balzasyn "I burned the arrow that killed Balza" (that -z suffix here is metathesized into the verb and devoiced, and we have a following epenthetic vowel)

Indirect object- Kasran eigu jezyn qirčinõmdaxuz xâż lenasyn "I see the clearing to which the tide gives water"

Oblique- Laxõždõn ðaka jeðõd qiršõmmaxnaz ewa "I broke the stone with which the shellfish hunted"

Genitive- Šommom qâra huż qiršymžac mez rênnażi "The basil that lost its leaves has died."

Object of comparative- Jenimon reňkum hud qirčinõnjanjaz han dõsyn "I have found the needle that is longer than me" (lit. "grows more than me")

A FEW TRANSLATIONS

I feel like translating some stuff, just to show a bit of the feel of it with either some familiar texts or maybe some stuff I decide to write for this. Again, no font, so I'll have to rely on my weird handwriting for this.

The One Ring inscription:

Verreðym gi grõn uda że cy, jeniðym gi że;

[verːeðɨm gi grən ɯda d͡ze t͡sɨ | jeniðɨm gi d͡ze]

rule-SUBJ-3S.Inan one ERG.DEF ring 3P.Inan all | find-SUBJ-3S.Inan one.DEF 3P.Inan

"One ring shall rule them all, the one shall find them;

Bêlašõðym gi grõn uda że cy, ta heqalxaz gŷšqamõðym że

[bɛlaʃəðɨm gi grən ɯda d͡ze t͡sɨ | ta heqalxaz gʷɵʃqaməðɨm d͡ze]

gather-SUBJ-3S.Inan one ERG.DEF ring 3P.INAN all and evil-LOC imprison-SUBJ-3S.Inan 3P.Inan

"One ring shall gather them all, and shall imprison them in evil"

Mordor jejaxtaz jõl xalzunõǧ tawna

[mordor jejaxtaz jəl xalzɯnəd͡ʒ taɣna]

Mordor territory-LOC where reside.3P.Anim shadow-P.DEF

"In Mordor land where the shadows live."

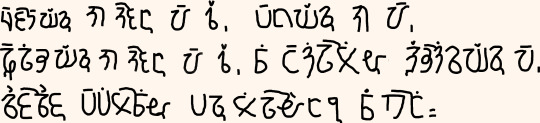

A few quotes from Goncharov and its promotional materials:

Jaqym grõn rêǧi Napolisyn

[jaqɨm grən rʷɛd͡ʒi napolisɨn]

come-3S.Inan ERG.DEF winter Naples-ALL

"Winter comes to Naples"

Ai fiłatõš syganõn; so, fiłacõnõn uri lun ðam qirčinymfiłac yaň sadusyn

[aj fiɬatəʃ sɨganən | so fiɬat͡sənən ɯri lɯn ðam qirt͡ʃinɨmfiɬat͡s jaŋ sadɯsɨn]

O lover apologize-1S | look love-COND-1S only 2S.ACC REL.how ANTP-HAB-3S.INAN-love\ANTP boot knife-ALL

“I’m sorry my dear, I can only love you the way a boot loves a knife.”

Kamassõnõl mainõ Napoliðõd žaz dajersyn qarrêðdõ Mâskõvaxaz ňaňňyz qa zazõðõǧ hud fiłatõǧ lun vaðdõd

[kamasːənəl majnə napoliðəd ʒaz dajersɨn qarːʷɛðdə mɔskəvaxaz ŋaŋːɨz qa zazəðəd͡ʒ hɯd fiɬatəd͡ʒ lɯn vaðdəd]

trace-COND-2S path-ACC.DEF Naples-ABL 1P.GEN home-ALL childhood Moscow-LOC man-GEN.P REL.who say-SUBJ-3P.Anim REL.what love-3P.Anim 2S.ACC blood-ABL

“you could trace a path from Naples to our childhood house in Moscow with the blood of all the men who’ll tell you they love you”

I'll probably do art and shit with this conlang at some point, and not just LOTR and Goncharov brainrot.

Enjoy!

#conlang#neography#why am i like this#goncharov#i am the flavor of dumb bitch who cant get goncharov out of my head so I translated quotes into my conlang#one is even from the movie poster what the fuck#is my trans ass becoming a film bro#i thought i stopped being a weird asshole in college#this is a cry for help

10 notes

·

View notes