#intraparenchymal hemorrhage

Text

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage Secondary to Rhino Orbitalcerebral Mucormycosis: A Case Report and Literature Review

Jasper Gerald R. Cubias* and Raymond L. Rosales

St. Luke’s Medical Center, Institute for Neurosciences, Section of Adult Neurology, Capital Towers, E. Rodriguez Ave., Quezon City, Philippines

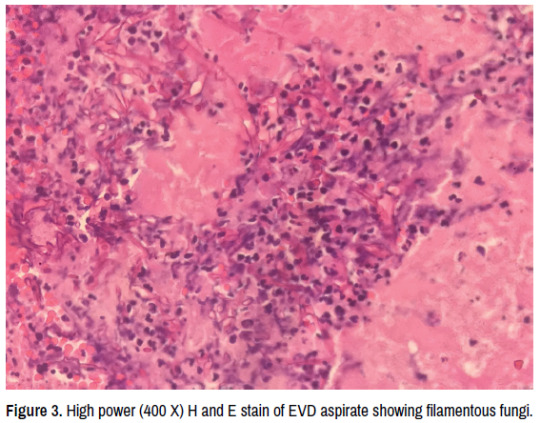

Mucormycosis is a rare invasive opportunistic fungal infection with high morbidity and mortality, with Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage (ICH) being one of the less common complications cited in available literature. In this case report, we present a case of a 65 year old Filipino diabetic male with non-small cell lung cancer and recent history of steroid use who presented with headache. This patient developed proptosis, chemosis, and purulent discharge from the right eye, and eventually had sudden onset decrease in sensorium on the 6th day of admission. CT scan showed findings of ICH on the right frontal and patient underwent craniotomy and evacuation of hematoma. Histopathology and culture findings confirmed the diagnosis of Rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis. The patient was treated with Amphotericin B initially then shifted to voriconazole based on culture and sensitivity testing. The patient was managed in-patient for 3 months and eventually survived 18 months from the diagnosis.

To date, no case reports of ICH secondary to Rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis are available in our locale. Additionally, patients from all previous published case reports all succumbed to the infection. This case demonstrates that a high index of suspicion and early workup is warranted in patients presenting with headache and having risk factors for mucormycosis. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment are keys towards achieving a good outcome in these patients.

For citation:

Cubias, Jasper Gerald R. and Raymond L. Rosales. â??Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage Secondary to Rhino Orbital-cerebral Mucormycosis: A Case Report and Literature Review.â? Clin Neurol Neurosurg 5(2022): 131

New manuscript submission link: https://www.scholarscentral.org/submission/clinical-neurology-neurosurgery.html

or

E-mail: [email protected]

0 notes

Text

Understanding Intracranial Pressure Monitoring Devices and its Versatile Uses

What are Intracranial Pressure Monitoring Devices?

Intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring devices are medical instruments used to measure pressure inside the skull and brain. As the brain is contained within a rigid skull, any swelling or hemorrhage can quickly raise intracranial pressure which can potentially lead to brain damage or death if not treated. ICP monitoring devices provide clinicians real-time data to help diagnose and treat conditions that affect brain pressure.

Types of Intracranial Pressure Monitoring Devices

There are a few main types of Itracranial Pressure Monitoring Device monitoring devices currently used in hospitals:

External Ventricular Drainage (EVD) Catheter: This device consists of a thin cylindrical catheter inserted into one of the brain's ventricles. The catheter is connected to an external drainage and monitoring system. It allows both drainage of cerebrospinal fluid to reduce pressure and monitoring of ICP levels. EVD is considered the gold standard for invasively measuring ICP.

Intraparenchymal ICP Probe: This minimally invasive probe is directly inserted into the brain tissue, most commonly in the white matter of the frontal lobe. It contains a pressure transducer at the tip that is connected to an external monitor. Intraparenchymal probes provide a slightly less accurate ICP reading compared to EVD but with less risk of complications.

Subdural Screw or Bolt: A small screw or bolt containing a strain gauge pressure sensor is surgically implanted through a burr hole in the skull and positioned between the dura membrane and skull. It directly measures pressure on the brain surface and is well-tolerated by most patients.

Get more insights on Intracranial Pressure Monitoring Devices

About Author:

Ravina Pandya, Content Writer, has a strong foothold in the market research industry. She specializes in writing well-researched articles from different industries, including food and beverages, information and technology, healthcare, chemical and materials, etc. (https://www.linkedin.com/in/ravina-pandya-1a3984191)

0 notes

Text

IntraCranial Guardian: Reliable Intracranial Pressure Monitoring Systems.

Introduction to Intracranial Pressure

Intracranial pressure (ICP) refers to the pressure inside the skull and brain tissue. The skull is a solid structure made of bone, preventing the brain from moving. Therefore, any increase in volume of the brain, blood, cerebrospinal fluid or brain tumors can increase ICP. Excessively high ICP can damage brain cells and tissues by reducing blood flow. It is critical to monitor ICP in conditions like severe traumatic brain injury, strokes and brain tumors.

Invasive Methods for Intracranial Pressure Monitoring

Intraparenchymal Monitors

Intraparenchymal monitors are the most accurate method for direct ICP measurement. They involve inserting a probe directly into brain tissue, usually on the frontal or temporal lobe. The sensor at the probe's tip transmits pressure readings to an external monitor. While accurate, they carry risks of hemorrhage, infection and sensor drift over time requiring periodic recalibration.

intraventricular Catheters

Intraventricular catheters are threaded into one of the brain's ventricles to measure pressure of cerebrospinal fluid, which correlates well with true ICP. They last 2-4 weeks on average before the risk of infection rises significantly. Catheter placement requires insertion into the brain under imaging guidance and has rare but serious potential for hemorrhage.

Non-Invasive Methods for Intracranial Pressure Monitoring

Transcranial Doppler Ultrasonography

This uses ultrasound pulses through the skull to measure blood flow velocity in basal arteries. Rise in ICP tends to decrease flow velocity, so it provides an indirect estimate of pressure changes. It has no risk of intracranial infection but underestimates very high pressures above 50mmHg. Accuracy also depends on operator skill and bone window quality.

Tympanic Membrane Displacement

A relatively new technique, it detects subtle displacements of the eardrum under very low frequency sound caused by ICP pulses transmitted through the skull. Potential disadvantages include inaccuracy in presence of middle ear infections or eardrum abnormalities. Further validation studies are still ongoing.

Ocular Ultrasonography

This assesses changes in optic nerve sheath diameter, which expands with rising ICP since the sheath is a direct extension of the brain's coverings. However, it is mostly useful to detect elevated rather than normal ICP ranges and can be impacted by other ocular factors as well. Additional research is still warranted.

Newer Generations of Intracranial Pressure Devices

Novel implantable sensors are now available that transmit ICP data wirelessly through the scalp, eliminating the risk of connecting percutaneous catheters. Additionally, advances in miniaturized electronics allow combining multiple sensor modalities into single compact probes. This helps continuous monitoring of ICP along with other critical parameters like brain tissue oxygen, temperature and pH. Such multimodal devices hold promise for improving outcome prediction and guiding therapy in neurocritical care.

Overall, accurate ICP monitoring remains invaluable for managing various acute and chronic neurological conditions. While invasive techniques are still preferred when the risk of intervention is justified, noninvasive options offer potential benefits of wider availability and avoidance of intracranial devices. Combining sensing technologies may further optimize critical care. With ongoing innovation, solutions are advancing to better serve unmet clinical needs.

0 notes

Text

Going to be a long day for me today. Got commissions to work on, set up a crockpot for dinner tonight, clean the house a bit, and then relax with minecraft with my friend later in the evening.

My first full week back to work is tomorrow. I know I didn't post here when it happened (this place was not on my mind tbh), so here we go! May 26th, I had two seizures that revealed I was having a rare type of stroke. It is a hemorrhagic stroke called Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage, and most of the time causes death or severe disabilities. Due to my wonderful partner's fast actions and the second hospital's talents and speed, I not only survived but woke up with no physical deficits. The doctors were shocked, they told us that I should have died with how bad my brain scans were. My first day back to work was this passed Friday though. It was very nice and I was genuinely missed and had a warm welcome from my staff and the management of the facility I guard. I'm a little nervous about doing a full week though, but hopefully all will go well!

Speaking of work, I plan on using my downtime there to work on the comic and using my time at home for commissions.

Anyway, that's all for today blog wise! Hope everyone has a wonderful day! 🥰

0 notes

Photo

Because subarachnoid hemorrhage surrounds cerebral blood vessels, it can cause vasospasm, potentially leading to infarcts in the brain. This is usually seen in the setting of diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to ruptured aneurysm rather than trauma, and typically manifests several days after the subarachnoid hemorrhage has occurred.

#epidural hematoma#subarachnoid hemorrhage#epidural hemorrhage#intraventricular hemorrhage#intraparenchymal hemorrhage

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Perhaps sick/injured fic and awful first meeting?

I took my liberties and made this Tanev/Kapanen because no ship was suggested!

Sick/injured fic + Awful first meeting 🔪

Kasperi wasn't ashamed to admit he shrieked--just a little--when the man on his autopsy table opened his eyes.

It seemed like a reasonable reaction at the time considering that the cool blade of his scalpel had been hovering mere centimeters from the pale ridges of the man's sternum.

Now it was on the floor and Kasperi was clutching the edge of his cart as if whacking it at the (zombie???) might do anything productive.

He should never have let Brian talk him into watching Night of the Living Dead.

The man blinked wearily, looking around the room with the kind of indifference you wouldn't expect from someone who’d only just woken up on the lowest level of the hospital. Very few of those who took the elevator to bastment ever surfaced.

Well, those who rolled in on four wheels.

The man heaved a sigh and sat up causing the limp black hair that hung around his face to stir. "Not again," he mumbled, tucking a few stray strands behind his ear, before turning his attention to Kasperi.

Some of the colour had returned to his tanned skin and his eyes; wide and hawk-like, where trained on Kasperi like the dark, empty, barrel of a gun.

Kasperi swallowed, It was only after another few beats of awkward silence that he realized he'd been asked a question.

"What?"

"Do you have my stuff?" The man repeated himself, slowly as if Kaperi was the one who had come into the hospital with a intraparenchymal hemorrhage.

"Yeah, give me a sec." Still reeling, Kasperi went to retrive the plastic bag filled with the man’s personal items--Brandon Tanev according to the sharpie scrawled across the front--from where he'd discarded it.

"Sweet," Brandon said, snapping his toe tag off with a practiced tug and stepped into his jeans, commando, just the way he'd come in.

"I thought you were dead, dude," Kasperi managed eventually when he was feeling slightly less insane.

"Yeah, I get that a lot," Brandon answered, straightening his shirt out over his chest. The cold white florescent light from overhead made his cheekbones stand out like jagged rock faces, bold black triangles cut under his eyes. “It’s kind of a thing.”

“Oh,“ Kasperi said, as if that were a reasonable reply to...all of this. He physically made himself unclench his jaw and ease his breathing as slowly the blood returned to his head. He let out a sharp, possibly hysterical laugh at the rush. His scalp prickled as if he’d tied his hair back too tight. Fought the urge to tug at the band and yanked off his gloves instead. He fought off another shiver as the wet patches in the armpits of his scrubs began to cool.

Brandon was doing up his sneakers with clumsy fingers as if he hadn’t regained full mobility in them yet.

Kasperi busied himself with retrieving his scalpel from the floor and placing it in the sink to be resanitized.

“Hey,“ Brandon said from behind him, closer than Kasperi thought he’d be, moving with an unsettling silence. Kasperi had sort of expected him to be taller. “I got to sort this out with admin,” he said in an long suffering tone that belied his situation. You’d think he was bemoaning a DMV line. “But it you ever find yourself in a similar situation with the spooks--“

With a wink he handed Kasperi something from his wallet, the dry brush of his fingers making something primal clench cold in his gut.

The business card read:

Brandon Tanev: Ghost hunter, Psychic, and Wight for all your paranormal needs!

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irons!Alfred's Injuries and Medical Conditions:

Stress cardiomyopathy

Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome

Borderline Personality Disorder

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage Damage from burst aneurysm (VD - v; trust me I'm a Doctor)

Multiple embedded Shrapnel injuries

Sciatica

Recurring Tinnitus due to blast damage (can trigger by stress, loud noises and heavy wind)

Phantom Limb Pains

Residual Limb pain due to amputation of lower right leg.

Major Depressive Disorder

Addiction to Alcohol (VD)

Addiction to opioids (currently under control)

Sparodic hypersexuality due to medications (VD)

Cervical Spondylosis (VD)

Mixture of Sensitivity Disorders, Auditory, Tactical and Introception based.

Trauma related sleep issues

Anxiety/Panic Disorder (VD - Alfie Based)

Mild haphephobia due to physical trauma

Muscle damage due to bullet wounds - 4 places.

Multiple long term side effects of 2 lead poisoning episodes.

(VD) - Verse Depending

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surgical Performance Determines Functional Outcome Benefit in the Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation (MISTIE) Procedure

Surgical Performance Determines Functional Outcome Benefit in the Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation (MISTIE) Procedure

Neurosurgery 84:1157–1168, 2019

Minimally invasive surgery procedures, including stereotactic catheter aspiration and clearance of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator hold a promise to improve outcome of supratentorial brain hemorrhage, a morbid and disabling type of stroke. A recently completed Phase III randomized trial showed improvedmortality but was…

View On WordPress

#Intracranial hemorrhage#Intraparenchymal hemorrhage#Minimally invasive surgery#MISTIE#Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

0 notes

Text

Surgical Performance Determines Functional Outcome Benefit in the Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation (MISTIE) Procedure

Surgical Performance Determines Functional Outcome Benefit in the Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation (MISTIE) Procedure

Neurosurgery 84:1157–1168, 2019

Minimally invasive surgery procedures, including stereotactic catheter aspiration and clearance of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator hold a promise to improve outcome of supratentorial brain hemorrhage, a morbid and disabling type of stroke. A recently completed Phase III randomized trial showed improvedmortality but was…

View On WordPress

#Intracranial hemorrhage#Intraparenchymal hemorrhage#Minimally invasive surgery#MISTIE#Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator

0 notes

Text

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage Symptoms, Causes, Treatment

Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage Symptoms, Causes, Treatment

Learn all about intraparenchymal hemorrhage symptoms, causes and treatment. Intraparenchymal hemorrhage is one extension of intracerebral hemorrhage) with bleeding within brain parenchyma.

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage accounts for approx. 8-13% of all strokes and results from a wide spectrum of disorders. It is more likely to result in death or major disability than ischemic stroke or subarachnoid…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Salivary Gland Tumor and Its Signs and Symptoms

Pleomorphic is a benign salivary gland tumor that has certain types of symptoms and signs. It is a slow-growing, painless, firm and non-tender mass; while it can move (when small) and become fixed as it enlarges.

Sudden increase in size and pain in a known pleomorphic adenoma may result in intraparenchymal hemorrhage. According to doctors, such type of salivary gland tumor is not life threatening.

There are different types of benign salivary gland tumors like Adenomas, warthin tumors, Oncocytomas and benign mixed tumors or Pleomorphic Adenomas that can be cured by surgery and by following the right steps of treatment. According to doctors, they are not cancers and don’t generally invade adjacent tissues or metastasize, but can continue to grow and become deforming. It is better to get them removed. A pleomorphic adenoma can transform into a malignancy, but in decades and chances are rare.

Pleomorphic Adenoma or other salivary gland tumors may occur due radiation exposure – radiation treatments for cancer – mainly one that is used for treating head and neck cancers may increase the risk of salivary gland tumors. It may be due to older age that is another risk factor, when this type of tumor can occur. Not to mention the workplace exposure that is mainly to certain substances may increase the chances of this tumor type.

You are advised to consult with doctors to know about the signs and symptoms and get the right treatment procedure.

0 notes

Text

5-29-22

"Okay Sandy I'm going to give you some morphine for pain and Ativan to help you relax," I feel the small air bubbles travel through her vein as I push the medication in her IV. I know she won't respond. Her lips are blue. Her tongue is slack, she to snores continuously. Her husband and sister at at the bedside. They called me her because she "jerked." Bodies do strange things while dying. They had been discussing the quilt draped across Sandy's lap. "Do you sew Lydia?" her husband, Paul inquires. "No, but I've always wanted to learn." Sandy had been an avid quilter, her husband and sister too. "If I can do it, anyone can," Paul reassures me. I'm more interested in sewing clothing, but I thank him and keep that too myself. Her sister mentions that she may not enjoy quilting as much, I presume because Sandy will be gone. "It's a beautiful quilt," I offer, trying to be neutral and supportive.

Many family members tell me things about the stranger dying in front of me. Paul struggles to show me a picture on his phone, "I can't find my photo app," he says while earnestly swiping the screen. "I can show you how to fix that after you tell me about the picture," I say. He shows me an image of a young girl with long brown hair and a silver tiara in her hair. Today is her birthday, she's celebrating somewhere in Pennsylvania. Paul tells me that she insisted on wearing the tiara because Sandy bought each of her grandchildren tiaras to wear on their birthdays. A lovely idea. I tell Paul how sweet the sentiment was. He hands me his phone and I hold down the photo app until the icons begin to wiggle, a text box appears with an option to add the app back to the home screen. I hand the phone back and he laboriously drags the app to where he wants it.

If the patient survives more than two hours after compassionate extubation they go to the Palliative floor, a pavillion over and two floors up. I knew Sandy would last that long. Some don't though, barely alive with jet fuel running through their veins. Sandy suffered a large intraparenchymal hemorrhage. She had a minimal mid-line shift which excluded her from receiving an external ventriculostomy drain. I had asked the neurosurgery resident two nights prior if she'd get one. "You make it sound like a prize," he jabbed, "I don't want her to get one." "I don't want her to get one either, but the family was wondering," I clarified. He called a few minutes prior to showing up at the bedside, his voice was laden with exhaustion on the phone as he asked me to pause Sandy's sedation so he could preform a neuro exam. The residents work 30-hour shifts on the holidays, Memorial Day weekend it had been. He was acting strange from sleep deprivation, I let his attitude slide. Medical management it was.

I hung 3% Normal Saline, a hypertonic solution to reduce cerebral swelling by osmosis, when Sandy was admitted. I kept the head over bed elevated, at least 30°, and twisted her neck so her head was midline, to facilitate CSF drainage. She had a left gaze preference, consistent with her brain injury. I put a towel roll next to her head so she couldn't twist it. Among everything else I did-- managing sedation, titrating vasoactive medications, frequent lab draws, and neuro exams--her exam never improved. Every two hours I pinched her shoulders and sternal rubbed her to elicit a response. Her left hand would slowly reach across her body in an attempt to stop the noxious stimuli. She had bruises from the pinching and the pressure. Sometimes I had to twist as I pinched or put my full body weight into my knuckles on her boney sternum to see her left arm move.

36 hours of torturous neuro exams later the family decided to go comfort cares--letting her die peacefully.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Incidental Discovery of Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma of the Anterior Mediastinum: A Case Report - BJSTR Journal

Incidental Discovery of Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma of the Anterior Mediastinum: A Case Report by Shi SX* in Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research

https://biomedres.us/fulltexts/BJSTR.MS.ID.006178.php

Liposarcomas of the mediastinum are uncommon, and those of the anterior compartment are even more rare. The majority of cases are symptomatic on presentation due to mass effect. We report the case of a large asymptomatic anterior mediastinal liposarcoma discovered incidentally during workup for intraparenchymal hemorrhage.

For more articles on Journals on Biomedical Science please click here

bjstr

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/Biomedres01

Follow on Blogger :https://biomedres01.blogspot.com/

Like Our Pins On : https://www.pinterest.com/biomedres/

#open access journals of biomedical science#Journal of Biomedical Research#journal of biomedical research and reviews impact factor#journal of biomedical sciences research review#journal of biomedical research and reviews

0 notes

Text

Outcome Following Neurosurgery of Acute Subdural and Epidural Hematomas in Patients Primarily Admitted to a University Hospital in Open Access Journal of Medical and Clinical Surgery

Abstract

The aim of this investigation was to study patient characteristics and long and short-term results specifically in patients primarily admitted to a neurosurgical department and operated acutely for acute subdural hematoma (ASDH) or epidural hematoma (EDH). Forty-five patients operated at Uppsala university hospital 2008-2019 were included (ASDH=39 and EDH=6): 28 men and 17 women, mean age 61 years (range 8-93), 76% >1 co-morbidity, 44% on anticoagulants/antiplatelets, mean hematoma width 20mm (range 7-37) and mean midline shift 9mm (range 0-26). Seventy-three percent had >3 characteristics indicating vital surgical indication, i.e preoperative unconsciousness (GCSM <5), pupillary dilation (one or both eyes), lucid interval, hematoma width >10 mm, midline shift >5 mm. Postoperative CT was improved in all cases. Proportion of patients responding on commands increased from 36% at admission to 69% at discharge. Favorable outcome was seen in 36% and 31% died (all ASDH, mean width 21mm, range 12-35, mean shift 13mm, range 4-26; mean age 70 years, range 43-87; 64% not responding to commands and 57% abnormal pupils on admission). In conclusion, substantial mortality and morbidity were found in patients operated for ASDH and EDH even if primarily admitted to a university hospital and operated by a neurosurgeon. Taking into consideration the substantial presence of negative pre-operative prognostic characteristics, the results may afterall be interpreted as relatively favorable. An important observation was that also patients with poor prognostic factors may sometimes have favorable outcome when operated without delay. The proportion of favorable outcome achived despite that many patients displayed features related to poor prognosis, indicates that the decision making to operate was appropriate, accepting also patients indicative of having relatively poor prognosis.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury; Acute subdural hematoma; Epidural haematoma; Acute neurosurgery

Introduction

Acute subdural hematoma (ASDH) and epidural hematoma (EDH) are common types of traumatic brain injury (TBI). ASDH comprised 30% and EDH 22.5% of 13,962 TBI patients registered in an European database 2001-2008 [1]. The corresponding figures for Sweden were 46% and 6%, respectively, among in-hospital treated patients 1987-2000 [2]. A review of the literature made for the Brain trauma foundation found mortality rates between 40-60% for ASDH [3] and around 10% for EDH [4]. It is well known that a delay of surgical evacuation may be detrimental both in ASDH and EDH, especially in patients losing consciousness [5-9]. In Sweden, as well as in many other countries, there may be long distances to the nearest neurosurgical department and many patients are primarily admitted to local hospitals and transferred secondarily to neurosurgical departments. When patients are admitted primarily to a university hospital with neurosurgery the time factor is usually limited and one are probably more inclined to take the chance to operate even patients with less favourble prognostic factors. It would be of interest to particularly study this group of patients. The aim of this investigation was therefore to study patient characteristics and long- and short-term results specifically in patients primarily admitted to a neurosurgical department and operated acutely for EDH or ASDH.

Materials and Methods

The Department of Neurosurgery at Uppsala University Hospital (UUH) provides neurosurgical care for 6 counties with one another university hospital, 5 county hospital and various smaller local hosptals. The total catchment area includes around 2 milj inhabitants of which 200,000 live in the Uppsala county region and are referred primarily to UUH. The longest distance from the most distant local hospital within the catchment area is 300 km. TBI patients treated between 2008 and 2019 at the Department of Neurosurgery, UUH, were selected from the Uppsala TBI register [10]. Inclusion criterion were: 1. ASDH or EDH (dominating injury); 2. acute admittance primarily to UUH and 3. acute neurosurgery performed at UUH. During this time 1102 TBI patients treated in Uppsala were included in the TBI registry. From this population, 391 patients were identified with ASDH or EDH as the dominating injury. Three-hundred-forty-six patients were primarily admitted to a local hospital and therefore excluded from further analysis, leaving us with 45 patients in the final study population. The following parameters were analyzed: age, gender, former and ongoing diseases, use of anticoagulants/antiplatelets, type of trauma, intoxication, lucid interval, major extracranial injury (requiring hospital care itself), global ischemia (circulatory or respiratory); and neurological reaction grade based on the Reaction Level Scale 85 (RLS) [11,12], presence of pupillary dilatation and paresis, at admission and at discharge from the neurointensive care (NIC) unit or step down unit, respectively. The correspondence between RLS and Glasgow coma scale motor score (GCS M) is described in Table 1.

Factors indicating vital indication for surgery were evaluated [13]: 1. Preoperative unconsciousness (RLS 4-8), 2. Pupillary dilation (one or both eyes), 3. Lucid interval, 4. Hematoma width >10 mm, 5. Midline shift >5 mm. Lucid interval was defined as when the patient was awake after the injury and later became unconscious. ICP monitoring, type of ICP monitoring, re-operation <24h and additional surgery during NIC (>24h) were investigated. The hematomas were analyzed regarding type, width, and midline shift on the CT-scans. The radiological outcome of surgery was assessed as improved, unchanged, or worsened by comparing the midline shift and the width of the hematoma between the latest preoperative and first postoperative CT-scan.

Clinical outcome was measured using the Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOSE) after around six months [14]. GOSE categories between 8-5 were assessed as favorable outcome and categories between 4-1 as unfavorable. Unknown or missing data were reported as unknown.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical methods were mainly descriptive. The data analysis was done in Prism Graph Pad 8. Fisher´s exact test was used for a significance assessment of the difference between groups. P-values <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

The demographics are presented in Table 2. There were 28 men (62%) and 17 women (38%), and the mean age was 61 years (range 8-93 years). Twenty-seven (60%) of the patients were >60 years. Thirty-four (76%) of the patients had one or more co-morbidity: hypertension or cardiac disease in 49% of all cases, past brain trauma or brain disease in 27%, history of alcohol abuse in 11%. Intoxication at the time of trauma was confirmed in 6 of the cases (13%). Twenty patients (44%) were on anticoagulants/antiplatelets.

The dominating types of trauma were fall accidents (71%) and traffic accidents (20%) (Table 2). Seven of the patients (16%) had one or more major extracranial injury (Table 2), i.e. extremity injury (n=3), facial fractures (n=2), spinal injury (n=2), thoracic injury (n=2), pelvic fractures (n=2), and extensive hemorrhage (n=1).

Preoperative CT-scan findings

The dominant finding on the preoperative CT scan was ASDH in 39 cases (87%) and EDH in 6 cases (13%). The mean hematoma width was 20 mm (range 7-37) and the mean midline shift was 9 mm (range 0-26).

Preoperative neurological status

Preoperatively, 29 patients (64%) did not respond to commands (RLS 3B-8/GCS M 5-1) (Figure 1), 17 patients had pupillary dilatation (38%; 1 unknown) (Figure 2) and 13 patients had paresis (29%; 2 unknown; > RLS 6/flexion not evaluated) (Figure 3).

Presence of vital indication

Preoperative unconsciousness (RLS 4-8/GCS M 5-1) existed in 20 patients (44%), pupillary dilation (uni- or bilateral) in 17 (38%; 1 unknown), lucid interval in 11 (24%; 6 unknown), hematoma width >10 mm in 39 (87%), midline shift >5 mm in 37 (82%) (Table 3). One factor indicating vital indication for surgery was present in 7 patients (16%), 2 factors in 17 (38%), 3 factors in 4 (9%), 4 factors in 15 (33%) and 5 factors in 2 (4%) (Table 3).

ICP monitoring

ICP was monitored in 32 patients (71%); 29 received an intraparenchymal pressure device, one received an external ventricular drain, and two received both.

Radiological outcome

Postoperative CT showed improvement in all patients who performed a postoperative scan CT examination (2 patients deteriorated and died before this was done).

Reoperation

A reoperation < 24 h was performed in one patient with removal av remaining hematoma and 5 patients had additional surgery later during NIC.

Short term neurological outcome

The mean duration from admission to discharge from the NIC unit or step down unit was 19 days (range 1-93). The proportion of patients responding on commands (RLS 1-3A/GCS M 6) increased from 36% (16/45) to 69% (31/45) at discharge (p=0.0029) (Figure 1). There were no obvious improvements regarding presence of pupillary abnormality (Figure 2) and presence of paresis (Figure 3).

Long term neurological outcome

Clinical outcome was assessed in mean after 7 months (range 5-10). Fifteen patients (33%) had good recovery, 1 (2%) moderate disability, 12 (27%) severe disability, 1 (2%) vegetative state, 14 (31%) had died and 2 patients (4%) were lost to follow-up (Figure 4). The outcome was classified as favorable (good recovery and moderate disability) in 16 patients (36%) and unfavorable (severe, vegetative, and dead) in 27 (60%). The 14 patients who died, had all ASDH and they died within 21 days after the trauma, 8 before discharge from NIC and 6 after discharge. When different potential prognostic factors were related to outcome (favorable and unfavorable), age >65 years and ASDH were significant negative prognostic factors and use of anticoagulants/antiplateles showed a tendency to be related to unfavorable outcome (Table 3). The patients who died had a mean age of 70 years (range 43-87), 36% (5/14) were RLS 7-8, 57% (8/14) had abnormal pupils, and the mean width of the hematomas was 21 mm (range 12-35) and the mean midline shift was 13mm (range 4-26) on CT (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study of patients primarily admitted to a neurosurgical department and operated acutely for an EDH or ASDH, we found that ASDH was more common than EDH and associated with a significantly worse outcome. We also found that males were overrepresented and that traffic accidents and falls were the most common causes of trauma. Hence, our cohort was similar to those in other comparable studies with regard to these results [1,15,16]. However, our patient cohort showed a high prevalence of unfavorable prognostic factors. The prognostic factor that most clearly differed from other studies [1,15,16] was age; the median age in our cohort was 68 years, and 60% of the patients were older than 60 years and 55% were older than 65 years. Furthermore, 76% had a previous disease/comorbidity, and 44% used anticoagulants/antiplatelets. Since age, history of prior disease, and use of anticoagulants/antiplatelets contribute to poor clinical outcome [1,15,17,18], our cohort was more likely to have less favorable outcome.

Overall, 37% (16/43; 2 unknown) of the patients showed favorable outcome in the particular group of patients studied (EDH: 5/5, one unknown; ASDH: 11/38, 29%, one unknown), which is within the ranges reported by others [7,14,15,19-24]. It is important to analyse the outcome results in detail in order to evaluate whether the decision to operate appears to be reasonable or too optimistic in acute patients admitted primarily to our hospital and if one can identify reliable prognostic predictors. The proportion of favorable outcome achived, despite that many patients displayed features related to poor prognosis, indicates that the decision making to to operate were indeed appropriate. When different potential prognostic factors were related to outcome, we found that age >65 years and ASDH were significant negative prognostic factors, and use of anticoagulants/antiplateles showed a tendency to be related to unfavorable outcome (Table 3). However, the predictive value of those factors were low because a considerable number of patients with age >65 years, ASDH and anticoagulants/antiplatelses had favorable outcome. This finding underline that a judgement that surgery are without chances should be based on a multifactorial analysis.

When evaluating the results, it is also important to look on the degree of vital indication, i.e. how urgent surgery was. With this purpose, five characteristics indicating vital indication were evaluated [13]. It was found that all patients included in the study had at least one parameter that indicated vital indication and a large majority (73%) had three or more (Table 3). Neither any specific characteristic of vital indication nor the number of vital indications showed significant relation to outcome, which was expected since precence of characteristics indicating vital indication was so common. It is, however, notable that also patients with 4-5 characteristics of vital indications had favorable outcome, which shows that such patients may have favorable outcome if acute surgery can be performed without delay. Furthermore, the outcome in relation to presence of vital indications further support that the decision making to operate was appropriate.

The overall mortality rate in this study was 33% (14/43; 2 unknown), all due to ASDH (14/37, 36%; one unknown), which can be compared with the mortality rates of 40-60% in ASDH [3] and around 10% in EDH (4) reported by the Brain trauma foundation. Detailed analysis of patients who died in our study showed a mean age of 70 years and large proportions of patients in RLS 7-8 with abnormal pupils and large hematomas with extensive midline shift on CT (Table 4). Overall, the characteristics of the patients who died indicate that they all had very poor chances to survive, except one 43-year-old man in RLS 3B on admission, although he had abnormal pupil reactions (Table 4). Thus, no obvious potentially avoidable deaths were observed.

When the distances from local hospitals to university hospitals with neurosurgery are long, there has been a tradition in some countries, including e.g. Sweden and Norway, that life-saving evacuations of ASDHs and EDHs may be performed by general surgeons at local hospitals. An earlier regional study in Norway, indicated that the clinical outcome was suboptimal for patients operated at regional hospitals, suggesting that perhaps all patients should be transferred to a university hospital for surgery despite the time delay [25]. In the region where we provide neurosurgical service, we have had a long-standing working routine that a general surgeon with neurosurgical training may perform an acute evacuation of an ASDH or EDH at a local hospital, after consultation of the neurosurgeon on call in Uppsala, if the operation is life-saving and the patient judget not to survive a delay of surgery [13]. The policy includes also that the patient after surgery should be referred to Uppsala for NIC [13]. When we evaluated the results 2005-2010 we found, on the contrary to the Norwegian study [25], relatively favorable results after acute evacuations of extracerebral hematomas performed in the local hospitals [13]. The results of the present study shows that the rate of favorable clinical outcome was even higher (51%) and mortality rate lower (18%) in the local hospitals. It is however important to highlight the differences with younger patients, more cases of EDH, less co-morbidity and less use of anticoagulants/antiplatelets in the local hospital series [13]. Even if the patient materials differ and are difficult to compare, we do think the results of this study concerning patients primarily admitted to a neurosurgical department not in any way contradict continuing the practice of acute evacuation in local hospitals when there is a clear vital indication in our health care reagion. It is however important to underline that the patient should be transferred for NIC after a life saving operation in a local hospital.

There are some methodolocical issues of this study which need to be considered. There were a limited number of patients studied and therefore multivariate statistical analysis or applying statistical model grading systems for outcome prediction was not possible. Detailed information about time courses, e.g. time from detoriation to surgery, was lacking. On the other hand, a strength was that a large proportion of patients with a considerable number of negative prognostic factors were operated, included and analysed, which provided the valuable information that relatively favourable results may be obtained also despite these conditions.

In conclusion, substantial mortality and morbidity were found overall in patients with ASDH and EDH even if they were primarily admitted to a university hospital and operated by a neurosurgeon. Poor results could to a large extent be explained by considerable presence of negative prognostic characteristics, e.g. poor neurological grade, high age, co-morbidity, anticoagulants, and preoperative indications of a clear need for instant surgical evacuation on vital indication. Taking these conditions into consideration, the results may afterall be interpreted as relatively favorable. An important observation was that also patients with poor prognostic factors may sometimes have favorable outcome when operated without delay. The proportion of favorable outcome achived (37%) despite that many patients displayed features related to poor prognosis, indicates that the decision making to to operate was appropriate accepting also patients indicative of having relatively poor prognosis.

Regarding our Journal: https://oajclinicalsurgery.com/

Know more about this article

https://oajclinicalsurgery.com/oajcs.ms.id.10037/

https://oajclinicalsurgery.com/pdf/OAJCS.MS.ID.10037.pdf

#Traumatic brain injury#Acute subdural hematoma#Epidural haematoma#Acute neurosurgery#oajcs#clinical surgery

0 notes

Text

Subarachnoid hemorrhage has noted characteristic findings on CT, which is shown in the exhibit. On CT scans, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) appears as a high-attenuating, amorphous substance that fills the normally dark, CSF-filled subarachnoid spaces around the brain. The normally black subarachnoid cisterns and sulci may appear white in acute hemorrhage. These findings are most evident in the largest subarachnoid spaces, such as the suprasellar cistern and Sylvian fissures. Subarachnoid hemorrhage typically presents as a sudden headache with maximal intensity at onset. It is usually described as a "thunderclap headache" and "the worst headache of my life". Associated symptoms may include nausea and vomiting, meningismus, or loss of consciousness. Sometimes there will be a "sentinel" headache occurring 6-20 days in advance of the subarachnoid hemorrhage which usually resolves spontaneously. Most subarachnoid hemorrhages are secondary to aneurysm rupture and may require neurovascular intervention to stop the bleeding.

Example of SAH: Blood noted in suprasellar and ambient cisterns. It can also collect in the various sulci. If the blood does not look like it is in the epidural, subdural, or intraparenchymal space, it is likely in the subarachnoid space. The picture is the typical image seen with SAH.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Juniper Publishers-Open Access Journal of Head Neck & Spine Surgery

Traumatic Subdural Hematoma and Intraparenchymal Contusion after a Firework Blast Injury

Authored by Luke GF Smith

Abstract

Firework injuries represent a common etiology of injury requiring emergency department evaluation every year, especially in the pediatric population. Typically, firework-related injuries tend to produce burn or blast injuries; however, there have been no reports of fireworks causing an intracranial hematoma. The authors report a case of a consumer firework directly impacting the head of a 6-year-old boy, causing neurological deterioration. Trauma evaluation discovered a subdural hematoma, for which the child underwent emergency hemicraniectomy for surgical evacuation. Despite the injury, he recovered with minimal neurologic sequelae. After one month, he returned for cranioplasty and experienced a favorable outcome after his traumatic brain injury with some mild cognitive deficits.

Keywords: Fireworks; Subdural hematoma; Traumatic brain injury

Abbrevations: GCS: Glasgow Coma Score; CT: Computed Tomography

Introduction

Firework displays are a frequently encountered and integral part of summertime holiday celebrations in the United States, although they do carry significant risk, especially in the pediatric population. Firework-related injuries comprise a small, yet significant, source of pediatric injury [1]. Since 1990, more than 5000 children were treated for consumer firework-related injuries in emergency rooms across the United States on an annual basis [2]. In 2014 alone, 10,500 firework-related injuries required hospital treatment [3]. While orthopedic and burn injuries to the hands compose the majority of these injuries, 22.0% of firework-related injuries involve the head or neck [2]. Furthermore, a significant percentage of these injuries are suffered by bystanders [3]. A small fraction of these injuries require hospitalization, and even fewer require operative intervention [4,5].

Pediatric brain injury due to projectile or explosive weapons in both civilian and military zones is well known [6-8]. While head injury caused by fireworks comprises approximately a fourth of all fireworks injury in children, there has not yet been a report in the literature of a firework impact causing an intracranial hemorrhage, much less an injury requiringemergency neurosurgical intervention. Herein we report a 6-year-old male bystander who suffered a consumer firework-related blast injury, requiring emergent hemicraniectomy for evacuation of a subdural caused by the fireworks impact.

Case Report

History and Examination

A 6-year-old boy with no significant past medical history was at a neighborhood party celebrating Independence Day. The boy was a bystander in a crowd when a large firework misfired and hit the boy in the right temple. Per report, the firework exploded on or around the time of impact. The boy reportedly lost consciousness briefly and was then transported to our institution

On initial presentation, the patient had a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 14 with confusion regarding the year and his location, in addition to left lower extremity weakness. He had a 5 cm burn over his right temple with surrounding facial edema. Computed Tomography (CT) of the head demonstrated a 9mm mixed-density right convexity subdural hematoma with 11 mm of midline shift (Figure 1). No skull fracture was identified(Figure 2). While in the trauma bay, he had a steady decline in consciousness. Due to the large subdural seen on imaging and concordant worsening exam findings, the decision was made to proceed with surgical intervention for evacuation of the hematoma (Figure 3).

Operation

A right-sided front temporoparietal hemicraniectomy with evacuation of a significant subdural hematoma was performed. A temporal parenchymal contusion was noted as the likely culprit of the subdural blood. Due to substantial cerebral edema, the bone flap was not immediately replaced. A right frontalintraparenchymal pressure monitor was placed, and he was taken to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit post-operatively. A post-operative head CT was performed, showing satisfactory evacuation of subdural hematoma and markedly improved midline shift (Figure 4).

Post-operative Course

His post-operative course was uneventful. Intracranial pressure remained within normal limits, and he briskly followed commands. On the first day following surgery, the intraparenchymal pressure monitoring device was removed, and he was extubated. He progressed well and was discharged on post-operative day 5. He returned 1 month after his initial injury for autologous cranioplasty and tolerated the procedure well without complications. At 5 months follow-up, he had returned to school with minor emotional outbursts and attention issues that were not present prior to injury.

Discussion

Fireworks, while a common part of many holiday celebrations in the United States, are an important etiology of pediatric injury. All common consumer fireworks have been known to cause injury, including death, incurring significant medical expenses [9]. However, significant firework-related neurological injury has not been previously reported in the literature. In the case discussed, we report a bystander child who incurred a serious neurological traumatic brain injury secondary to an aerial consumer firework used at a neighborhood firework display. Due to the severe injury, the child underwent a major surgery for evacuation of intracranial hematoma. Additionally, the patient required multiple days in the intensive care unit, required repeat admission for bone flap replacement, and had lasting cognitive effects

Surprisingly, firework-related injuries to pediatric bystanders is reported in 26% of all fireworks injury cases [4]. Greater than half of the reported cases include adult supervision, demonstrating that even adult supervision does not necessarily prevent these types of injuries [4]. Public education initiatives about the dangers of fireworks have also failed to translate tomeaningful changes in rates of pediatric fireworks injury [10]. The American Academy of Pediatrics has advocated for abolition of all consumer fireworks, encouraging attendance solely at public fireworks displays [11]. Given that consumer fireworks can cause pediatric head injury similar to that seen in weapon projectile or blast injury, as demonstrated in the case presented, this stance is reasonable [8].

Given the uncommon nature, traumatic brain injury secondary to cerebral blast injury may be missed on initial presentation, leading to a delay in diagnosis [12]. Recognition that consumer fireworks can cause these severe and potentially operative injuries is important in their overall treatment. The case reported here highlights the first reported case of severe traumatic brain injury and intracranial hemorrhage secondary to a firework-related injury, denoting the need for increased public knowledge of the danger of consumer fireworks

For more articles in Open access Journal of Head Neck & Spine Surgery | Please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/jhnss/index.php

For more about Juniper Publishers | Please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/pdf/Peer-Review-System.pdf

0 notes