#it and conceptualize it and apply it to their lives. the different frameworks within which the same traits can be categorized in different w

Text

I think there are three large classes of socialist concern, which are not reducible to each other and which require different types of solutions. I would describe them as follows:

Distributional concerns — Markets tend towards inequality, and thus even in times of abundance fail to allocate resources to people who need them.

Concerns over autonomy — Private control of resources, especially when it is highly concentrated, comes at the cost of the autonomy of those who don't control the resources. As a significant special case of this, private control of the means of production deprives workers of autonomy over their own work, which constitutes most of their waking lives. Concentration of property in the hands of the few leaves most people with no choice but to sell their labor, turning them into workers deprived of autonomy in the above sense.

Humanistic concerns — Markets optimize for specific outcomes and, furthermore, the desirable properties of market economies are predicated on the existence of firms which optimize for profit. In both cases these optimization procedures are premature; they do not factor in the full human condition and thus come at the cost of many things which people find desirable.

In my view, a successful socialist program must at least attempt to address all three of these concerns. Often when debating other socialists, I feel that they err by focusing on some of these concerns to the exclusion of the others.

I have listed these concerns in order of how difficult I believe them to be to solve. Concern (1) can, in fact, be solved relatively easily even within a liberal economic system, by implementing massive redistributive taxes that equalize wealth. I want to stress that this proposal is still radical by the standards of any nation on earth today, but a solution is easy to imagine. And all these problems are interrelated; solving (1), for instance, would go a long way towards remedying (2).

Concern (2) can also, I think, be solved or at least greatly mitigated under a market framework, though not a classical liberal one. Replacing private firms wholesale with worker co-ops would go along way towards addressing (2), and in combination with the above solution for (1) provides I think the easiest to conceptualize vision of what a workable socialist (socialist enough) economy might look like.

Concern (3) is by far the hardest to address—it is in essence just the alignment problem as applied to economic systems. Suffice it to say, the problem remains open.

A common theme I see in debates between certain (usually more liberal-leaning) practically-minded socialists and certain (usually more radical) utopian-minded socialists is that the practical socialist will propose some solution that aims to address (1) and (2), and the more utopian-minded socialist will respond with vague and often not particularly coherent accusations of insufficient radicalism. The practical socialist will often then reply by dismissing the utopian's criticisms as nothing but hot air, as unserious radical posturing. But I think this represents an unfortunate misunderstanding. That utopian is often pointing at something real, even if it is articulated in a way that offends more pragmatic sensibilities. Concern (3) touches on every part of human life, I think it's fair to say, and though the habit of incoherently blaming everything that goes wrong on capitalism is not that useful, it doesn't point at nothing.

The alignment problem is not solved in the general case, but there are things we can change about a system to try and make it more aligned with specific, known goals. So the job of a good socialist (or really, anyone interested in any kind of political reform) should then be to listen to the ways in which people are dissatisfied with their lives, even when articulated poorly, and try to accrue an understanding of the most recurrent and significant ways in which the present system fails to satisfy people. Then you can look for specific tweaks that will more readily accommodate the things people in fact seem to want. But crucially, this task in empirical—you cannot come upon the most desirable tweaks rationally. It's also empirical in a way that is difficult to approach with any kind of scientific rigor. You have to listen to people, and try to understand them on their own terms. You have to try to understand where people are coming from even if they phrase things in a way that you very much dislike, a way that irritates you or makes you feel threatened.

As I've said before, "listen to marginalized voices" is oft-misused, but not actually incorrect as a description of the practical obligations of anyone who wants to consider themself a leftist.

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

#010

Modern myths (?) and how to engage

Every time I process things with friends or alone I write a little summary here, often about the same topic, so to the two people who read me, I'm (partially) sorry.

Anyway, I'm someone who is often parked squarely in what I call the "bold claim UPG", or the experience that is very "extraordinary" in the purest sense of the term, in which sometimes I'm posed with apparently information about the gods (bear with me, there's a point). I often come back to this topic because I'm trying to wrap my head around my experiences and UPGs without getting in over my head or lost in the proverbial sauce. And honestly? No idea if I'm doing a good job of it. Maybe I'm being too "down-to-Earth" and dismissing important experiences, or maybe I'm tripping too much and believing illusions.

That's the point I think I'm trying to hammer down in my head: I can't know with absolute certainty which of these scenarios is true. So I've wrote a few times about what I perceive to be the inherent loneliness of spirituality, the importance of being level-headed, and just discernment in general. But I think that dealing with this kind of thing is less of a set formula, and more like... having a bunch of different tools under your belt and applying them as needed.

So this is another tool I've conceptualized for me and pouring out here.

I'm a firm believer that often the UPGs we get are the UPGs we need - in other words, people experiencing a deity in completely different ways doesn't mean one of them has a truer truth, it just means that this is how the deity decided to present for whatever ending they're aiming at with these different individuals.

I also think sometimes deities play certain roles we create for them in order to connect to us through that door we opened, so if we "demonize" a certain deity too much or "sanctify" another too much, they are likely to play along in some occasions to meet us where we are and still get us to do what we need to do. So, for example, if you "demonize" a deity a lot, they might double down on that perception to get you to improve your wards or to get you to seek assistance of a guide you would have otherwise ignored. Of course, mind the nuance here.

This to say, sometimes we get a modern version of a myth about our gods, and when we are sometimes posed with undertakings or information about the gods that seem too "fantastical" or "exclusive", like "there's an interdimensional cosmic war between the gods and they're gathering up an army on Earth", it's time to take a step back not necessarily to dismiss it, but to engage with it healthily. Again, please mind the nuance.

What I've processed as another tool in helping with that is:

Establish an anchor point

Set a certain personal code/goal to serve as compass through the fog, and engage with things through that. If you have this "anchor" at ready, you will be able to remain firmly grounded as you process what you're experiencing. This can have many forms: a personal philosophy/framework, a deity whose characteristics represent what you want to remain near to, a trusted friend with whom you can process things together, a set of protocols to digest the UPG... Anything that could be a balanced space to allow you to reflect safely.

Conceptualize some analysis points for the experience: "what is this experience making me think about? What stands out as the overarching theme here? What concrete actions am I being driven to? How does it fit within my personal code? What different perspective can I apply for a broader understanding?"

I doubt that as individual humans we're gonna be the ultimate key to resolve some sort of big cosmic war, but I do believe that we can be summoned to alleviate the suffering of fellow living humans and even do some work on the spirit realm! Ultimately, it doesn't mean that it's a smaller, irrelevant work, it's absolutely just as vital as the rest, BUT my point is that focusing too much on the big interdimensional cosmic war might stray us from the things that we need to develop here and now. It might have us miss what purpose this narrative might be serving in our lives.

So, in the end, they're sorta like myths! We often don't take them literally, we just interpret the message and purpose they carry between the lines. They were, after all, the ancient people's UPGs once. But to get to that, first we need to identify that we might ourselves be living through our own myths :)

#deity work#norse loki#lokean#norse pagan#norse paganism#polytheism#upg#witchcraft#discernment#no idea if this is gonna make sense

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Brief

Synopsis of Study

The Jurassic Coast is England’s only natural World Heritage site. Stretching 95 miles, it goes from Orcombe Point to Old Harry Rocks. The Jurassic Coast holds 185 million years of earth history, covering the entire Mesozoic period, including the Jurassic era. Around 200 million years ago, this shoreline was completely submerged by tropical sea, making it one of the best areas to collect fossils. I want to inform people of the history and collections that can be found along the Jurassic Coast.

Applying different techniques and mediums, I will produce an informative composition utilising the history and collections I gather along the Jurassic Coast. I will incorporate different elements and skills of Visual Communication, such as, colour, print making, texture, typography and use them to create a visually interesting and outcome. I will look at the texture and patterns of the matter I gather and the location they are found. I’ll consider the context in which my outcome will be viewed and how the context could enhance the viewers experience. I will be looking at the term ‘slow movement’ and how the activity of ‘beach combing’ and ‘Fossil Hunting’ can encourage individuals to live a slower lifestyle, thus aiming the outcome towards those living a busy lifestyle who either live near the Jurassic Coast or are visiting the area. I will also research the work by Mary Anning and how her work has impacted contemporary fossil hunting and beach combing.

This relates to my future aspirations and my own specialist practice as a visual designer who appreciates the medium of printmaking and typography.

Ethical Issues

There can often be ethical issues surrounding the collection of findings on the beach, specifically fossils. However, fossil hunting is legal and ethical as long as the fossils are loose. It is unethical to dig or hammer them from cliffs. In regards to collecting other beach matter, it is ethical as long as I don’t collect anything alive or the habitat of an animal, i.e. spiral shells as hermit crabs often depend on them for their survival.

Aims

A1: I will identify links between my specialist topic and relevant theoretical and conceptual frameworks through independent led research and critical understanding.

A2: I will strengthen my ability to define problems and generate ideas using different approaches to solve them appropriate to an identified audience.

A3: I will develop my creativity, knowledge and understanding of practice through the effective use of communication in professional contexts.

Learning Outcomes

LO1: I will demonstrate my understanding of relevant theoretical / conceptual frameworks through my independent led research and critical understanding.

LO2: I will demonstrate my ability to problem solve using different approaches and defining my ideas in relation to audience / user / viewer.

LO3: I will generate effective communication that demonstrates:

- Solutions that show an awareness of contemporary practice within professional contexts.

- Work that shows a high degree of creativity and aesthetic judgement.

Assessment Component

A body of work containing sketchbooks, process book, blog posts and worksheets showing my design process: research, analysis, ideas development and final designs.

I need to name / label all digital files correctly and submit them.

I need to present my final outcome to a professional industry standard.

100% body of work (tutor assessed)

References

Eylott, M.-C. (no date) *Mary Anning: The unsung hero of fossil discovery*, *Natural History Museum*. Available at: https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/mary-anning-unsung-hero.html#:~:text=Mary%20Anning%20was%20a%20pioneering,being%20made%20to%20this%20day. (Accessed: May 4, 2023).

F. Last Modified Date: April 06, M. (2023) *What is the slow movement?*, *Cultural World*. Available at: https://www.culturalworld.org/what-is-the-slow-movement.htm (Accessed: May 4, 2023).

Countryfilemag (2022) *Beachcombing Guide: Things to find along the seashore and Best Beaches in the UK*, *Countryfile.com*. Countryfile.com. Available at: https://www.countryfile.com/how-to/outdoor-skills/beachcombing-guide-things-to-find-along-the-seashore-and-best-beaches-in-the-uk/ (Accessed: May 4, 2023).

Honoré, C. (no date) *In praise of slowness*, *Carl Honoré: In praise of slowness | TED Talk*. Available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/carl_honore_in_praise_of_slowness (Accessed: May 4, 2023).

Edmonds, R. (1999) *Discover dorset fossils*. Dovecote Press.

0 notes

Text

CVL - Evaluation - SD

I feel that applying/understanding conceptual and theoretical frameworks was the strongest aspect of my unit’s development. Firstly, coming into the project with personal experience with the concept helped me to quickly able to sympathise with the audience as well as understand the impact of bereavement on a person. Bringing my own experience to this project really helped make it feel personal and considered. Developing from this, applying theories to my practice really helped me quickly develop more concepts. Foucault’s ‘Heterotopia’ theory helped me gain an understanding of how ‘other’ spaces (e.g. graveyards) are able to inform culture as well as form pockets of time in which people experience time uniquely. Other books such as Susan Sontag’s ‘Illness as a Metaphor’ helped form my understanding of illness as an experience and informed me not to explore the illness conceptually itself but rather the impact it may have on others. Research from previous projects such as Transhumanism also helped to push me towards digital methods of producing outcomes due to the idea that the human condition can be improved using developing technologies. Many contemporary artists conceptually pushed my project such as Rachel Whiteread, Shezad Dawood, Jake Elwes and Lu Yang. Jake Elwes’ practice in particular helped me reevaluate my personal knowledge of contemporary practice and particularly emerging technology such as AI and its politics. Lu Yang’s ‘Great Adventure of Material World’ also helped inform my final product’s concept by being a digital product helping to resolve real-world personal issues. Having this piece as inspiration helped solidify my usage of VR mediums to help children grieve. Overall, I feel I successfully understood and applied theoretical and conceptual frameworks.

In terms of considering the target audience of bereaved children, I feel I demonstrated a good understanding of the audience and their needs. Using sources for research such as Child Bereavement UK helped me understand and consider children’s understanding of death at different ages and how this may affect the design of the experience. Adapting the register applied in text for children of different ages helped to consider things such as reading levels and how children of different reading levels may interact with the experience. I also identified that when children experience bereavement, they may feel lonely or insecure, therefore it is imperative that the VR installation is not solely for children but getting the surviving parent involved would be a better feature to implement. Encouraging dialogue between children and the surviving parent about the deceased strengthens both of the child’s relationships with the parents and allows the child to understand that they have a safe emotional environment to express their grief. The aesthetic of the experience is more lively rather than gloomy, encouraging the child to celebrate the life of the deceased rather than upsetting them. The application of bright colours and playful, disjointed, pixelated design elements makes the environment stimulating for older children (but does not exclude younger users) and makes them eager to explore and discover things about their deceased parent, despite the serious tone of bereavement.

Previously in my projects, I felt I struggled to find research resources that showed an understanding of contemporary practice conventions. With this project, however, I feel I included research from a lot more contemporary sources, especially with the emphasis of my study looking at VR, AR and AI. In terms of VR and AR research sources, digital spaces and installations such as ‘this place [of Mine]’ and ‘Night in the Garen of Love’ helped encourage my understanding of how VR and AR can be used both to preserve memory and explore future possibilities for spaces in the future. ‘Night in the Garden of Love’ helped me to understand the importance of interactivity within VR and the different ways in which interactivity can be implemented. VR as a method of preservation is also finding an interesting place in culture. The island of Tuvalu recently used photogrammetry and VR in order to preserve its land and culture from rising sea levels. The fact that VR is being implemented as a form of preservation of memory in order to allow space for grief makes the nature of my project feel relevant and in line with contemporary practice. One aspect of forming my understanding of contemporary practice I could have improved on was conducting contemporary aesthetic research more effectively, as I feel it could have better visualised a brand identity for the VR experience. This project also allowed me to begin initial research into AI and its current applications within design. Recently, concerns have been raised as to AI’s power in replicating voices using a small amount of learning material. There have been concerns as to whether this could be implemented in crimes such as identity theft, however, after researching AI voice cloning I feel we should discuss its positive attributes and possibilities in memory preservation and therapeutic voice modulation. After researching ideas such as ‘inner child work’, I believe that there is a great opportunity for AI voice cloning to be used in forms of grief-recovery tools and that including this in my project could offer people some form of closure or catharsis. It could be argued the idea of trauma work and revisiting old wounds itself is relevant to contemporary practice as recovering from past traumas and their effects are often a topic of discussion surrounding mental health in modern-day culture.

I feel my project displays a good degree of creativity and creative problem-solving. By implementing VR and AI into potential solutions for grief and bereavement, I feel that I have created an effective solution using unconventional methods of production and unconventional cultural codes surrounding loss. With the emergence of platforms such as the Metaverse revolutionising the way in which we work and communicate with one another, it would be remiss not to consider the ways in which these technologies would alter the way in which we grieve. Incorporating ideas and visual styles surrounding online culture I felt to be an interesting niche to work into this project. The idea that remnants of people are left online for people to access is a very relevant and interesting idea to play with so, by invoking that idea in my work, gives my work a unique selling point and concept. The aesthetic is intentionally unrefined and playful, helping to make the space feel judgement-free and safe. Having unrefined, unmatching decorations and objects doesn’t only make the space stimulating and energetic (subverting hegemonic ideas of grief) but also creates a sense of relatability. This is a space that is imperfect: one to explore and make your own safely and without external judgment. I do wish however that I was able to explore the aesthetic and concepts behind it more thoroughly and were able to experiment with a more developed visual identity for longer. My Blender skills have developed throughout this project and I am happy with what I achieved but I feel I could have produced a more aesthetically appealing product through more skill development.

1 note

·

View note

Text

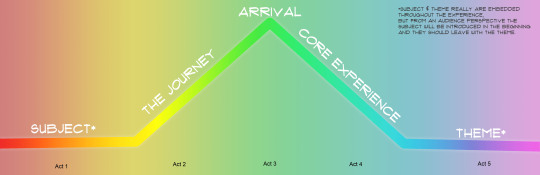

Five Act Structure And Themed Experiences

Ok so now you have your four pieces of framework. Now what? Well let's look now at classic five act structure. You'll remember it from English class. I'm no expert, but here's my summary

Act 1: Exposition: the world is introduced

Act 2: Rising Action: the main character sets out on a journey

Act 3: Arrival: the character achieves their initial goal. But at the midpoint of this act something happens which changes the equation and sets them on a new journey

Act 4: Journey Home: character sets off on the final quest. The final confrontation occurs at the transition to act 5

Act 5: Resolution and Denouement

The key thing to remember is that each key moment in the story occurs at an act transition, with the third act split in two - the key reversal occurring there. (All of what I'm about to say could be mapped onto 3 act structure too, but I think 5 makes it easier to talk about).

So anyway...you're building a ride. What goes where? Well I'd propose that nearly all attractions follow a simple rule. The Journey is everything that happens before the midpoint and the Core Experience is nearly everything that comes after. The theme and subject are what color each scene within and determine the ultimate outcome.

In modern attraction design it looks something like

Act 1: Entrance and early queue. The setting and world are introduced.

Act 2: Queue: the queue takes us on a journey into the world on our way to a promised experience (not always the core experience, but often). We learn about the world, and it's rules, and why we're there.

Act 3 Part One: Preshow: We arrive at the promised destination and new information is revealed that will set us on a new quest.

Act 3 Part Two: Load/secondary queue: The core experience (which follows its own three act structure) begins

Act 4: The Ride: We live out the meat of the core experience which leads us to one final climatic moment.

Act 5: Climax & Exit: We experience the climatic moment of the core experience, and the story quickly resolves itself as we exit the vehicle with a denouement then or shortly thereafter.

For example Indiana Jones and the temple of the forbidden eye

Act 1: We come across an archeological dog at a temple

Act 2: We venture into the temple to see what's up and learn this is a creepy place.

Act 3: Part 1 : we come across Sala and he tells us about quest expeditions we've somehow signed up for and the legend of the forbidden eye. Also we need to find Indy.

Act 3 Part 2: we decide to go on our own expedition (the core experience begins)

Act 4: The expedition throws up many obstacles of increasing threat level, preventing us from rescuing Indy until

Act 5: we nearly get crushed by a Boulder and narrowly escape. Indy lectures us since we were the ones that needed rescuing and we slowly make our way out of the scary temple.

Or Rise of the Resistance

Act1: we find the rebel base

Act 2. We are tasked with a mission to space but something goes wrong

Act 3 Part 1: We're captured and thrown in prison

Act 3 Part 2: We're rescued and begin our prison break (core experience)

Act 4: we journey through the prison facing increasing obstacles trying to make our way home until

Act 5: a final climatic encounter and daring escape pod run. We're told we did a good job and exit.

As long as queues are long, and rides are short I predict this is the specific way we'll see the structure implemented. What's interesting though is looking to the past to see how rides and attractions then still followed the same structure BUT implemented it differently.

For example, before queues were really designed as part of the experience, it was common for the ride to begin as early as the beginning of Act 2. Let's reference Pirates of the Caribbean (California version)

Act 1: We are introduced to New Orleans square and the Blue Bayou.

Act 2: We begin a journey through the bayou and enter mysterious caves

Act 3 Part 1: We learn that pirates used to inhabit these caves

Act 3 Part 2: The pirates materialize and the core experience of seeing pirates do pirate things begins

Act 4: Pirates do pirate things until

Act 5: The town climatically burns down, they all drunkenly kill themselves, and we exit this fever dream and end up back where we started.

Now consider how pirates was adapted when it moved to Florida and it adopted the new fangled immersive queue. The immersive queue replaced The Journey portion of the ride leaving only the core experience. The overall structure of the story was preserved, but what elements achieve it changed.

There's even a ride that has a more unusual implementation. Let's look at The Living Seas. For starters

Theme: The ocean is majestic and cool

Subject: Seabase Alpha

Core Experience: Explore an Alien World (And/or aquarium)

Journey: Specialized technology takes us deep under the sea

Now:

Act 1: We're introduced to the history of sea exploration in a museum and documentary

Act 2: We begin our journey under the sea via Hydrolator

Act 3 Part 1: We take sea cabs to further our journey

Act 3 Part 2: We arrive at Seabase Alpha

Act 4: We explore Seabase Alpha (core experience)

Act 5: We leave Seabase Alpha via Hydrolator

This is the only attraction I'm aware of that used has used the ride as a journey rather than the core experience. It's an unusual implementation but it just goes to show that any means can be used to achieve any part of the structure, as long as all parts of the structure are there, you get yourself a satisfying experience.

The more I think on it, the more I think nearly all attractions can be conceptualized in this framework, and better yet this framework provides a nice blueprint to develop new attractions. Does it apply to your favorite?

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

That's a great way to describe the nature of human nature. A lot of our instincts stem from useful shortcuts like that.

Human brains didn't evolve to handle the vast interconnectivity, complexity, and nuance of the modern world. Hell, the brain can't even really handle more than ~150 meaningful personal connections.

We operate deeply by back-of-the-napkin heuristics that solve our early evolutionary problems, but they're not very accurate. It's easier to get it right 70% of the time in one second than it is to get it right 100% of the time in thirty seconds. When a snowball (or lion) is flying at your face, moving at all is better than sitting around while you verify the threat's trajectory precisely.

Unfortunately, our tendency to align with those around us (a convenient heuristic sometimes still) isn't the sole problem here.

Some of these heuristics/instincts are naturally buffered. For example, one might imagine that the tendency (or inevitability) for people to bifurcate and fracture larger groups into less-than-150 sized groups is enough to minimize the problem, but just because it feels fine doesn't mean the result is fine. We form tribes on the spot for all sorts of reasons. Team A, Team B. My group, your group. Soccer teams, military platoons. Clades of styles and habits bloom and wither like algae tides. As a species, we crave that aspect of tribalism so deeply that sometimes a well placed "us" and a weaseled in "them" is enough to draw the lines that become a riot. This tendency can be positive sometimes (sometimes), sure.

What about our tendency to over-value sugar in a world where calories are no longer worth storing? That is a known-and-visible problem, isn't it? And how about the fact that a single mouse-click can show you more naked ladies than one's ancestors saw in their entire life - multiples more, in fact? It seems obvious that distorting such critically important evolutionary impulses miiiiight muddy the waters a bit even if we allow ourselves to believe that we handle it fine, that all is well, or that it's even somehow ideal.

Even these examples of specific and "obvious" discrepancies between our bioevolutionary hardware and our socio-technological elevation is a small enough as an idea to share with a stranger over a beer. The Real Heavy Shit™ is so unwieldy that a scientist-philosopher would struggle to gaze at directly, let alone transmit to others in a format smaller than a series of structured TedTalks.

The reasons for the issues we're facing (and in a sense have always faced) are myriad, but in recent times I think a new dynamic has been born, magnified, then bootstrapped itself into life beneath our notice - all within a single human generation. Information has become a danger to us. Any information. It is an emergent property that rises from the quasi-computational substrate of human social interaction.

Problem: When the complexity of an idea rises above the level of one's ability to conceptualize the 'entire thing' at once, we have to take the parts we can't see on faith.

With the proper framework, foundation, and a well-trained instinct this isn't an entirely disruptive phenomenon - it's even obvious and expected, right? One cannot hold the entire subject of 'science' in their head at one time. One cannot even hold the entirety of 'geology'. And even if one could, you'd be unable to truly understand geologic mechanisms without understanding that the elements that make all those fancy rocks came from dynamics that stem from astrophysics.

These things cannot be held, but they can be traced and compared and tested (if someone cares to do so in the first place). Even then, misconceptions easily bloom like cancers in the absence of an effort to validate.

Now consider the idea of an informational construct that is not so easily proven by mere effort and time. Imagine one that isn't built specifically to avoid misconception like science is. (which - unfortunately - still results in vast misconceptions by layman and scientist alike). When we cannot hold an idea in our head from start-to-finish, we also cannot verify that it exists distinct from itself at all. One can't tell a snake from an ouroborous. And unless you have something to compare it to, reference it against, the difference between a cancer and an organ is negligible. It's only in the context of an organism that a cancer is even harmful, even deadly. A cancerous tumor, viewed in a vacuum, is - for lack of a better term - successful as fuck at what it's doing... Perpetuating itself at all costs, regardless of benefit, regardless of consequence.

Ideas are not just informational nuggets. They're active, living systems which 'compete' not unlike living creatures do through the rules of their unique brand of quasi-evolutionary pressures. Ideas are both organs and cancers. And when billions of thinking beings are unable to easily determine the difference between an organ and a cancer, well... It's not so difficult to imagine that problems might arise.

To the elucidated or aware, it's horrifying to see someone running around trying to share a poison with others, claiming it to be something it is not. It's confusing to imagine how such a delusion can not only exist at all, but to spread with a veracity greater - far greater - than Real Deal truths. I will admit that part of that is because these sort of ideas empower the thinker. Real truths are either boring or frightening (or both). Aliens and crystals, gods and secret societies are so much more comforting than acknowledging that nobody is really at the wheel, that society is a ship in a storm rocked by systems - hydrodynamics, meteorological - far too complex to grasp, far too large to be defeated by comparatively meek human drives.

There's certainly more than one reason that someone interested in particular subjects (flat earth, for example) tend to also be interested in toxic conservative politics, religion, ancient aliens, so on. Many of these sort of meme-laden ideas are fundamentally incompatible with each other, yet you commonly find them in the same place. I personally use invented terms like "psychological antivirus/firewalls" since the concept of common sense alone doesn't have the load-bearing capacity to address this level of metastasized information.

Again -- A cancer is successful in a vacuum. It is optimized for relentless growth in absence of both usefulness and sustainability. Modern pressures (namely a social density vastly greater than what our brains can handle and the fast-paced war-for-attention nature of the internet) are now selecting ideas not for value or consistency, but transmissability.

Close your eyes and apply this metaphor to the rest of the world. Taste the horror of this truth, then consider that the issue can barely be described at all, let alone compressed down and shared to the world like some sort of hotfix. Following the metaphor, it'd be like writing a well-worded essay to convince your immune system to recognize an autoimmune disorder. You can't "Hey, bud. We need to have a talk." to a virus.

Christ, we can't even convince people to vaccinate against an actual virus that can be seen and verified as both real and harmful. This informational plague of idea-viruses is not only not-visible, hidden by abstraction, too recent to be intuitive, too large to even be named - some are seen by its victims as positive, absolute, worthy of defending with one's life even as one denies it exists at all.

Unfortunately, even this is just one of the many reasons why/how the modern world is simply too much for the smart apes known as homo sapiens.

TL;DR - Modern pressures (namely a social density vastly greater than what our brains can handle and the fast-paced war-for-attention nature of the internet) are now selecting ideas not for value or consistency, but transmissability. Some people are more ideal as carriers and vectors than others, but most of us have felt the sensation of being drawn into something or slowly waking up from a stupor we were born into.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

SUN IN SAGITTARIUS.

Sagittarius: Mutable Fire

Ruler: Jupiter

Keywords: Inspiration, Truth, Expansion, Meaning

Functional Expression: Inspired, seeking knowledge, visionary, fortunate, joyful, purposeful, philosophical, adventurous.

Dysfunctional Expression: Unprincipled, narrow, fanatic, reckless, gluttonous, coarse, rude, amoral.

Expansion and Growth.

When the Sun makes its’ journey through the sign of Sagittarius, the emphasis is on expansion, positivity and growth. Life is best seen as a journey, rather than a destination.

Along the way, Sagittarius brings the need to experience life as an adventure – to discover what is over the next horizon or how far one might go. To this end, those born under Sagittarius tend to love a challenge – finding ways to push past the “envelope” and so broaden perspectives somehow.

As a Fiery and Mutable sign – implying a constant need for change – Sagittarius brings an emphasis to physical and/or mental expression. The quest for freedom and adventure, as well as the search for meaning, tends to feature strongly for those born under this sign

Sagittarians are often characterized by an optimistic, outgoing and “can-do” attitude. Unless other, more introspective influences are present the birth chart, you will usually find Sagittarius where the action is.

This is a sign that loves nothing more than to live life large. When things are going well, those with Sun in Sagittarius are typically convivial, outgoing and good-humoured. Freedom is important and they will be willing to take a risk. This sign requires the space to roam unimpeded, and will usually give others the same in return.

It is important to feel that they have options, and nothing to tell them “no”.Whether they seek this freedom in the world of ideas, or find this freedom on a race-track, Sagittarians push limits and test boundaries to discover how far they can go.

Broadening Horizons.

With the Sun in Sagittarius there can be a tendency to get ‘itchy feet’ if things get too similar or mundane. For this reason, Sagittarius is associated with the experience of travel, and contact with foreign people or places.

In the quest to encounter new experiences, going where they have not been before, Sagittarius can find freedom. Again, life can easily get far too routine for those born under this sign. When this happens, they might find themselves feeling frustrated and so start dreaming up a way out.

When Sagittarius gets restless, it is important they broaden horizons somehow. Going somewhere new is an excellent way to keep life experiences fresh. Sometimes a jaunt to an exotic location is just the thing they need.

At other times, this can be accomplished by visiting a new neighbourhood or restaurant. An important strategy involves making time to travel and discover the unknown.With the Sun in Sagittarius they may invest more time and money in travel than in paying down the mortgage. When Sagittarians feel free they can share their positive energy easily.

Under a Lucky Star.

Sagittarius has a reputation for luck and achievement. Many excellent sportspersons, promoters and gamblers are born to this sign. Yet what might appear as luck is often the unbeatable combination of positive expectation coupled with an eye kept firmly on the prize.

One symbol for this sign is The Archer, and Sagittarians have a way of aiming true – firing themselves directly toward an intended target. Fortune favours the brave, and so, luck follows them around whenever they believe in themselves and the winning roll.

Because their approach to life is basically positive, Sagittarians expect things to go your way. And because they have this expectation, things usually do.

The Sun in Sagittarius prefers making broad strokes with a flamboyant brush, living by the philosophy that more is more, and good things are bound to happen. This positive mindset is another way to challenge limits and boundaries. Through taking risks and coming out on top they discover how far they can go. Every cloud has a silver lining – which sometimes turn to platinum – whenever Sagittarius is around.

Accepting Limits.

Yet all this positive expectation also has its’ drawbacks. Sagittarians can be known for brash, self-centred or excessive behaviour. Because they do not not believe in limits for themselves, they do not apply them when dealing with others.

With the Sun in Sagittarius, they can take things to extremes, or expect liberties from others because they refuse to bow to convention. Hence, they are often accused of being blunt to the point of rudeness or frank beyond socially accepted norms. Sagittarians can ride roughshod over the feelings of others, simply because they know they can.

They can be fickle, opportunistic and inclined to run at the first mention of committment. Some Sagittarians will push a situation to breaking point, just to see if they can. This can lead to broken relationships and instability. A Sagittarius who wont acknowledge limitations often creates excess that in the end proves detrimental.

This can be more of an issue for males than it is females, but the Zodiac is never gender specific. The excessive, fiery and expressive qualities of this sign mean that Sagittarians can love nothing more than testing the limits of physical endurance.

Excessive consumption of food, alcohol or other recreational activities can be detrimental. Pushing their luck until they are ruined may be the only way they know when to stop. As this sign is ruled by Jupiter, they can be prone to diseases of the liver or pancreas, as well as other degenerative diseases that are brought on by excess. Learning to live within the limits is an important part of the Sagittarius journey.

The Nature of Belief.

At a deeper level, the sign of Sagittarius is connected with belief. The journey toward greater levels of experience also involves broadening the mind. By comparing and contrasting different ideas, philosophies, belief systems or cultures, Sagittarians gain new perspectives.

They can enjoy expanding mental horizons through various forms of study, or the contemplation of comparative cultural, spiritual and philosophical values. Even if not studying formally, they are often found watching documentaries or reading non-fiction to learn more about the world.

At a conceptual level, this sign is associated with philosophy, religion and the broad mental frameworks which generate culture. At a personal level, through comparing philosophies Sagittarius can explore the nature of belief.

With the Sun in Sagittarius, there is often a need to explore many different belief systems along the way finding their own truth. By gathering a variety of perspectives, Sagittarians learn principles which they can then share with others.

As this sign is connected with the teacher and the student, Sagittarius broaden horizons through learning about various beliefs. These beliefs need to be experienced, rather than just talked about.

Sun in Sagittarius will not believe something because they are told to. They need to explore and experience it for themselves. At their finest, Sagittarians can inspire others through the broadness of their perspective. By taking the journey to teach and learn, they discover the inspiration to help others be the best that they can.

Yet the road to exploring the nature of belief can be fraught with danger. Once again, the threat of excess can rear its head. Typically, when Sagittarians encounter something they believe in, they become enthusiastic and want to share it with others. In the rush to spread ‘the good news’ they may ignore others right to discover things for themselves.

They can shift from “teacher” to “preacher”, getting up on their “soap-box”. Sagittarians can fall prey to zealotry under the belief that they have the truth and others do not. They then easily succumb to self-importance and inflation, believing themselves to be visionary advocates for a noble cause.

They might push their version of the truth down others throats because they believe in it so strongly. At a symbolic level, religious conflict is ruled by this sign. With the Sun in Sagittarius it is important to remember that they need to allow others the same level of intellectual freedom that they expect for themselves.

When Sagittarians share what they have learned from an open perspective, others willingly listen. But when they try to force a point of view, people will instinctively switch off. To share their experience they need to take the urgency out of it, and channel their passion into education rather than “reform”.

Alternately, some Sagittarians can become so disparaging in their search for truth that they become cynical or dismissive. Because their journey is to find out what is true for them, they may reject the beliefs of others, and see these as feeble-minded or simplistic. Then they may lose faith in life through the underlying (and unexplored) belief that they already know all there is to know.

It is easy for them to think there is nothing left to learn. Yet beneath their cynicism is a deep need to find an underlying belief system that can make life meaningful. A Sagittarian with nothing more to explore is a troubled soul.

Their journey involves exploring the nature of hope and faith. They need to maintain faith in order to have the courage to go beyond. Rather than limiting their philosophical options, cynicism can be just another stop along the road toward understanding.

Life should be experienced as a journey toward greater levels of illumination. For many Sagittarians a clear sense of belief may not be reached until even the age of 80. Yet along the way, they most not lose hope. Faith and optimism are essential to find deeper meaning.

Sun in Sagittarius: Your Solar Journey.

Born with the Sun in Sagittarius, you are gifted with an abundance of warmth, energy and positivity. Your sign is noted for a willingness to transcend the everyday by pushing boundaries, demanding freedom and seeking to explore unchartered horizons whenever possible. Your journey involves discovering all that is possible. Your ruler Jupiter brings luck, expansion and opportunity to your door, if only you will take it.

At a deeper level, your sign is concerned with the cultural, philosophical and metaphysical frameworks which make life meaningful. Your journey involves searching for truth and then sharing its manifestation. The path you take should be loud, large and colourful. Through collecting experiences and working out what is true for you, you inspire others to have the courage and faith to do the same.

#astroworld#astrology#astrotips#aries sign#taurus#gemini#cancer sign#leo#virgo zodiac#libra#scorpio#sagittarius#capricorn#aquarius#pisces

13 notes

·

View notes

Link

The “world historical defeat” of the female sex continues apace.

Women in their tens of thousands are trafficked into sexual slavery every year. Increasing numbers of poor, black and brown women are virtually imprisoned on commercial surrogacy farms, producing babies for the benefit of rich couples. Brutalisation of women in the porn industry is feeding through into its viewers’ sex lives, with grim consequences, while teenage girls face an epidemic of sexual harassment at school and on the streets.

The frequency of female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage has shot up during the Covid-19 crisis. Domestic violence has likewise rocketed. In the UK, prosecutions are so limited that rape is virtually decriminalised. Abortion rights are under attack, from the USA to Poland. And international ‘men’s rights’ networks like ‘Men Going Their Own Way’ attract millions of viewers to videos that dehumanise and pathologise women to an extreme extent.

This is a resurgent global system of exploitation and oppression targeted on women, a reaction against the many gains of feminism. The increasingly commercial nature of many of these deeply exploitative and oppressive practices - the porn industry, for one, makes billions every year, some of it from content involving rape, child abuse, non-consensual filming and the like - drives home the desperate need for a socialist analysis that exposes the roots of these ancient but enduring patriarchal oppressions. And we need an understanding and a language that enables that analysis.

But at the same time as this shocking acceleration of anti-woman attitudes, practices and policies, the categories of ‘man’ and ‘woman’ are being rapidly taken apart in response to a worldwide ‘trans rights’ movement. In a rush to embrace the new world of multiple genders, organisations and corporations as diverse as Amnesty International, Tampax, the stillbirth charity, Sands, the Harvard Medical School and many others are in a sudden rush to delete the words ‘woman’ and ‘girl’ from their vocabulary and replace them with a new, ‘inclusive’ language of ‘menstruators’, ‘gestational carriers’, ‘birthing people’, ‘cervix-havers’ and ‘people with uteruses’.

At the same time, the word ‘sex’ has progressively been replaced by the word ‘gender’, which is used to refer not only to reproductive class, but also to aspects of human life as disparate as individual psychology, personality, mannerisms, clothing choices and sexual roles. And the words ‘male’ and ‘female’, ‘man’ and ‘woman’, are being repurposed to refer not to the sexes themselves, but to aspects of psychology, personality or clothing that are traditionally associated with one or the other sex.

Is this new language - and the renaming and breaking up of the category of people formerly known as women - the tool we need for the job of dismantling the worldwide discrimination, exploitation and abuse of women that is so often focussed on the female sexual and reproductive characteristics? I would argue not. These misguided attempts to dismantle the language used to describe women’s bodies and lives does nothing to reveal or dismantle the oppression itself.

This is because the conceptual framework that is driving the change in language - and stretching and distorting the categories of man and woman into meaninglessness - is fundamentally wrong. And badly so.

Sex as fiction

The political driver behind these linguistic changes is the ‘trans rights’ movement, which bases its arguments on the most extreme and illogical aspects of queer theory. Many trans activists insist that to even question the precepts that they advance is actively hateful, even fascistic in nature - witness the social media furore when any celebrity, such as JK Rowling, dares to say that the word ‘woman’ means a female person. But it is neither hateful nor fascistic to question arguments that have neither intellectual nor political integrity.

I will quote from Judith Butler’s book Gender trouble1 - first published in 1990, and often hailed as a foundational text of queer theory - and its 1993 follow-up, Bodies that matter2, to illustrate the thinking behind the current trans activism movement. Queer theory is an unashamedly post-modernist, anti-materialist and psychoanalytic school of philosophical thought that frames sex, sexual behaviour and sexual identity (being gay, bisexual or straight) as social constructs, and takes its arguments so far that it claims that the two sexes (not just gender, but the sexes themselves) are fictional. The phenomenon of intersex is thought to prove that sex is not ‘binary’, with only two possibilities, but exists on a spectrum between male and female (I, among many others, have debunked this notion elsewhere3). But in queer theory, gender is not just “the social significance that sex assumes within a given culture”.4 Queer theory goes much further, purporting that the two sexes themselves are social constructs, like money or marriage. Thus gender replaces sex altogether: “... if gender is the social construction of sex, then it appears not only that sex is absorbed by gender, but that ‘sex’ becomes something like a fiction, perhaps a fantasy.”5

Therefore, according to queer theory, male and female are not objective realities, but ‘identities’. Everyone is required to fit into one or other of those two ‘identities’ in order to enforce reproduction through “compulsory heterosexuality”:

The category of sex belongs to a system of compulsory heterosexuality that clearly operates through a system of compulsory sexual reproduction … ‘male’ and ‘female’ exist only within the heterosexual matrix … [and protect it] from a radical critique.6

It is therefore through the power of language, and the naming of male and female, that gender oppression is created; and it is by the power of language that it can also be defeated. In order to dismantle the oppression that has resulted from this categorisation, it will be necessary to implement an “insidious and effective strategy … a thoroughgoing appropriation and redeployment of the categories of identity themselves … in order to render that category, in whatever form, permanently problematic”.7 This feat is to be achieved specifically by “depriving the … narratives of compulsory heterosexuality of their central protagonists: ‘man’ and ‘woman’”.8 The category ‘women’ is particularly promoted as being ripe to be emptied of meaning. It should be

a permanent site of contest … There can be no closure on the category and … for politically significant reasons, there ought never to be. That the category can never be descriptive is the very condition of its political efficacy.9

It is evident that the programme of queer theory is working, in the sense that it is changing and dismantling the language. But does the whole of gender oppression across history really originate in the simple naming of male and female? Because, if it does not, then this new movement is a dead end that is ultimately doomed to failure as far as challenging the structures that bear down on women’s lives.

While it is true that human thought and culture must have developed in tandem with the particulars of our species’ sexual behaviour, reproductive biology and mating systems - such as menstruation, which, although not unique to humans, is unusual among mammals - it is futile to protest that sex did not exist prior to the emergence of the human race.

Queer theory, however, rejects any understanding of human sex or gender that involves biological sciences. Our evolutionary history simply disappears in a puff of smoke:

... to install the principle of intelligibility in the very development of a body is precisely the strategy of a natural teleology that accounts for female development through the rationale of biology. On this basis, it has been argued that women ought to perform certain social functions and not others; indeed, that women ought to be fully restricted to the reproductive domain.10

For those who believe that reproduction is the only societal contribution appropriate to the class of people that possess wombs, by virtue of the fact that they possess wombs, altering the use of the word ‘woman’ cannot change that. It is the reproductive ability itself, not the words used to describe it, that the argument is based on. Nothing materially changes - moving words around will not change the position of the uterus, or its function. It is as futile as rearranging the labels on the deckchairs on the Titanic. Or like renaming the Titanic itself after it has hit the iceberg - thus, miraculously, the Titanic will not sink after all.

Many of the abuses and exploitations that oppress women target the real sexual and reproductive aspects of women’s bodies - our materiality - so a materialist analysis is essential. Can any such analysis work, when its starting point is that sex is a fiction?

Applying Occam’s Razor - accepting the simplest explanation that can account for all the facts - queer theory’s conceptual framework does not cut the mustard. If sex is a fiction invented to enforce heterosexuality and reproduction, it leaves vast swathes of the picture unexplained. An analysis worth its salt would bring together multiple, seemingly different, inexplicable or unconnected aspects of social and cultural attitudes to sex under one schema. A materialist analysis that takes into account the reality that there are two meaningful reproductive sex classes fares far better, and explains far more of the problematic - and often bizarre - social and cultural practices and attitudes around sex.

Is it not a far better explanation that people became aware of the blindingly obvious early on in human development - that there are very clearly only two reproductive roles, and that the anatomical features associated with each are astonishingly easy to identify at birth in nearly all humans? And that the possession of those distinct anatomies resulted in them being named, in the same way that other significant natural phenomena are named - because, irrespective of any relative value placed upon them, they actually exist?

Leaving aside that blatantly obvious counterargument, there is a further problem with queer theory: homosexuality just does not need to be eradicated in order to ensure reproduction. Why? Because occasional heterosexual intercourse, at the right time, during periods of female fertility, is all that is needed. A woman could sleep with a man just once or twice a month, and have it away with another woman for 20-odd nights a month, with exactly the same reproductive outcome. While it is true that there would be no reproduction if every sexual encounter was homosexual, strict heterosexuality, or anything approaching it, is not required to ensure childbearing. Likewise, a fertile man can sleep with a woman a few times a year and be almost certain to father children. And since one man can impregnate many women, significant numbers of men could be largely or exclusively homosexual without any impact on the number of children born - so why persecute and punish homosexual behaviour so severely?

The ‘compulsory heterosexuality’ argument has no basis, once examined in this light, and thus a central plank of queer theory falls easily.

Queer theory proposes that the so-called ‘complementary’ aspects of masculine and feminine behaviour have been created by culture in order to justify the compulsory pairing of male with female. Genders, including the two sexes themselves, are understood to be performative: brought into being by repeated ‘speech acts’ that, through the appearance of authority and the power of naming, actually create that which they name.

Thus, each individual assumes - or grows into, takes on and expresses - a ‘gender’ that is encouraged, promoted, and enforced by social expectations. I broadly agree that many of the observable average differences in male and female behaviour are largely culturally created, and reinforced by oft-repeated societal expectations. The fact that the expectations have to be so often stated, and sometimes violently reinforced, is testament to the fact that those differences are in no way innate, but are driven by the requirement to conform. But the origin of the expectations of ‘complementary’ male and female behaviour is not, as queer theory suggests, to counteract homosexuality and force the pairing of male with female.

The specifics of masculine and feminine behaviour do not point towards such a conclusion. Why is feminine behaviour submissive, while masculine behaviour is dominant? Why not the other way around? Why must one be dominant and the other submissive at all? Wouldn’t a hand signal do instead? How do the particular, specific manifestations of gender serve the purpose of enforcing heterosexuality and eliminating homosexuality, when many of them, such as FGM, reduce heterosexual behaviour in heterosexual women? True, any enforcement would require bullying of some kind, but why is it that so much of the bullying related to sex focuses on (heterosexual) women, and so relatively little on heterosexual men? Why is virginity in women prized but of little account in men? Why is so much actual heterosexual behaviour, that could lead to reproduction, so viciously punished? Why are women punished, humiliated, shamed far more than men for sexual promiscuity - heterosexual promiscuity? Why is it girls, not boys, who are the primary victims of child marriage practices? Why, in so many cultures, are women traditionally not allowed to own property, and children are considered the property of the father and not the mother? What answer does queer theory have to all this? None. It is not even framed as a question that needs to be answered.

Patriarchy

All of these disparate cultural practices spring sharply into focus when we understand the simple rule formulated by Friedrich Engels, the primary and founding rule of patriarchy, which exists to enforce the rights, not of men in general, but specifically of fathers: when property is private, belonging to male individuals rather than shared communally, women must bear children only to their husbands.

Why? Because the mechanics of reproduction mean that, while a woman can be certain the children she is raising are indeed her own, a man cannot - unless he knows for sure that the children’s mother cannot have slept with any other man. Thus when private property is concerned, men have a strong motivation to ensure that the children to whom they pass on their wealth are their own offspring. Herewith the origins of monogamous marriage. And with it, as an integral part (indeed as a driving force), the origins of women’s oppression - or “the world historical defeat of the female sex”, according to Engels.11

The gender rules developed in order to ensure paternity and inheritance. This simple explanation takes us a long way to understanding the specifics of how gender oppression manifests itself globally, in the enforced submission of women to men, and specifically to their husbands, and in seemingly disparate cultural values and practices that prevent women from having heterosexual sex with multiple male partners, outside of marriage, or punish them if they do.

How do men, individually and collectively, stop - or attempt to stop - their wives from sleeping with other men? Promises are not enough, as we know. How do you stop anyone from doing something they want to, from expressing their own desires? You bully them. You humiliate, threaten, harass, attack and perhaps - occasionally - even murder them. In these multiple ways you seek to enforce compliance, through assuming social dominance and forcing social submissiveness and subordination. Society and culture evolve around these values, and develop in ways that satisfy the needs and desires of the socially dominant group. Meanwhile members of that socially submissive group are discouraged from banding together (they might mount a revolution), and learn to adapt their own behaviour to avoid harm. And, since conflict is costly, disruptive and traumatic, both groups develop strategies to signal their social position, to defuse and avoid conflict and possible injury, with social rules and expectations developing around these behaviours.

The global hallmarks of masculinity and femininity would be recognised in any other primate species as the unmistakable signs of social dominance and social subordination. Socially dominant primates (and other mammals, plus many other vertebrates) make themselves large, take up space, monopolise resources. These are the core components of masculine behaviour. Subordinate animals drop or avert the gaze, make themselves small, move out of the way, and surrender resources. These are typical feminine behaviours. In primates, attending to the needs of the dominant members of the group, by grooming, is also characteristic of social subordinates. In humans, grooming as such has been replaced by a far broader suite of behaviours that involve serving the needs of the dominant class.

Gendered behaviours and the social values attached to each sex reflect this pattern worldwide. Societies globally and throughout time promote and encourage these masculine and feminine behaviours - better understood as dominant and subordinate behaviours - as appropriate to men and women respectively. Western cultures are no exception.

The enactment of dominance (‘masculinity’) and subordinance (‘femininity’) can be understood as partly learned and partly innate. Innate, in the sense that the expression of these behavioural patterns is an instinctive response to a felt social situation, or social position - anyone will signal submissiveness in the presence of a threatening social dominant who is likely to escalate dangerously if challenged. Thus, nearly everyone signals submissiveness extremely effectively, and unconsciously, as soon as they have a gun pointed at their heads. And it is hard not to display these behaviours, when we feel ourselves to be in the presence of a socially dominant or subordinate individual or group.

So femininity is a stylised display of primate submissiveness - a behavioural strategy that reduces or avoids conflict by reliably signalling submission to social dominants. Members of either sex, when they find themselves towards the bottom of any social hierarchy, deploy different, but similarly ritualised and reliable, submissive gestures. Examples include bowing, curtseying, kneeling or prostration before monarchs; the doffing of caps with downcast eyes and slumping shoulders in the workplace; and the kneeling and bowing (in prayer) that is such a large part of patriarchal organised religions. It is easy to recognise such gestures as signals of submission to social superiors, and they should be opposed as manifestations of social hierarchies that need to be abolished as an implicit part of the project for universal liberation. Neither the bowing and scraping of the dispossessed nor the arrogance and high-handedness of the wealthy should be welcomed or celebrated. It is time to apply the same approach when it comes to gender.

Moving beyond their instinctive component, the specifics of so-called ‘feminine’ or ‘masculine’ behaviour are learned and then practised until they become habitual; and sometimes deployed consciously and strategically. People do what other people do; children start to mimic others around them, especially those they perceive to be like themselves, at a very young age, perfecting gestures, postures and vocal tones that may be cultural or, within each culture, gendered. Learned and practised from a young age, it is no wonder that these behaviours can feel like a natural part of a person’s core being - especially when they also incorporate an instinctive response that is deployed after rapidly gauging the level of threat posed by others. In addition, both sexes are explicitly taught to behave as expected - and so the dominance of males and the subordination of females is reinforced and perpetuated from one generation to another.

Anything that undermines the position of men as dominant and female as subordinate is a threat to the established order. Thus the second rule of patriarchy: men must not act like women, and women must not act like men.

This explains why homosexuality, cross-dressing and other forms of refusal to conform to gendered expectations are persecuted in many societies. For men to start acting ‘like women’, either sexually or socially – ie, submissively, which has come to include being penetrated sexually - would be to undermine and threaten the superior role of all men. Similarly, for a woman to act ‘like a man’ is a shocking insurrection - she must be kept down, and such behaviour has to be punished and made taboo. Since clothing and other behaviours are cultural markers that help to distinguish between the two sexes, cross-dressing breaks this law very blatantly. And further, to allow cross-dressing potentially allows the mixing of the sexes in ways that could undermine paternity rights.

On this reading, then, the persecution of homosexuality, cross-dressing and all other forms of gender non-conformity originated secondarily from the enforcement not of compulsory heterosexuality, but of compulsory monogamy for women in the interests of ensuring paternity rights. This is an important distinction, for, while it accepts that gendered behaviours and values are cultural, it acknowledges the material existence of the two sexes as a real and significant phenomenon, with powerful influences on societal development.

Combating oppression

Understanding and placing ourselves as animals with real, material, biologically sexed bodies - rather than the smoke-and-mirrors erasure of sex and materiality itself that queer theory promotes - gives us a far more powerful tool to understand and combat the oppression of women, and homosexual and transsexual or transgender people, than queer theory’s baseless speculations ever can.

It explains not only the different social and cultural values and expectations around men and women, but it also explains many of the specifics of what they are and why the expectations are so strongly hierarchical. Women must be submissive to men (‘feminine’) because they must be controlled - from the male perspective, in order to bear children fathered by the man who controls them. From their own point of view, they must allow themselves to be controlled, and teach each other to be controlled, in order to avoid injury or worse. It also explains widespread cultural practices that control the sexual lives and reproduction of women - from FGM to child marriage, to taboos around female virginity and pregnancy outside of marriage. These things happen because sex is observable, and real, and known from birth. At birth, it is in nearly all cases blatantly obvious whether a person can be reasonably expected to be capable of bearing a child, or of inseminating a woman, and it is on this basis that the two sexes exist as classes. To suggest otherwise is to enter the realm of absolute fantasy, or at least of extreme idealism, which indeed queer theory does, since “to ‘concede’ the undeniability of ‘sex’ or its ‘materiality’ is always to concede some version of ‘sex’, some formation of ‘materiality’.”12

The current queer theory-led trans movement seeks to dismantle the second law of patriarchy - men must not act like women, women must not act like men. We do indeed need a movement against sex-based oppression that acknowledges and unites against that law. We need to work towards a world where qualities like strength, assertiveness, caring and gentleness are rewarded, encouraged and promoted in both sexes rather than mocked and punished when they are exhibited by the ‘wrong’ sex; where it is impossible for men to act ‘like women’, or women to act ‘like men’, because gendered expectations attached to each sex no longer exist and anyone can, without censure or even mild surprise, be an engineer or a carer, be logical or emotional or wear a dress or make-up or high heels or a tie or cut their hair short, irrespective of their sex. But to pretend that the sexes themselves do not exist is a nonsense. And it is a dangerous nonsense, when it obscures and denies the existing power relations between men and women.

Female oppression is not an inevitable consequence of the differences between male and female bodies. Yes, the fact that men are bigger and stronger on average can make it easier for them to establish social dominance through direct physical threat; while the risk of being left literally holding the baby and having to provide for it can put women in an economically vulnerable position, where social subordination is a likely outcome. But under different material conditions - and a different value system - there is no reason why we cannot shed these destructive, dysfunctional habits of gender that oppress and limit our humanity.

There is nothing inherent in being a man that makes men oppress women - it is their position in society that allows them to do it, and rewards women who collude with them. Power is the ability to harm without being harmed yourself, and therefore, with sufficient motivation, many people when they have power will use it to cause harm. Currently, men very frequently have that power in relation to women, and so they use it, resulting in very many harms. When, within any given social grouping or class, men occupy a position of power with respect to women, it is not an inevitable effect of human biology: it is a position gifted by property, by wealth, by tradition and by law.

We must seek to rebalance power to prevent harm. That involves, among many other things, abolishing both masculinity and femininity - no progressive cause should support or perpetuate a social system in which dominance is encouraged in one group, while social submissiveness is promoted in others. It is absolutely contrary to all ideas of human dignity and liberation. How could any liberatory movement adopt a position that posits an innate, inescapable hierarchical system at the heart of human nature, with close to 50% of humanity born inescapably into a submissive role?

But in today’s gender debate, the position of queer theory-inspired trans activists is exactly that. For them, to be a ‘woman’ is not to be female, but to be ‘feminine’- in other words, to be a ‘woman’ is to be submissive. It is here that we begin to see the true social regressiveness of this supposedly liberatory movement. For, while it is understood that biology does not determine the gender of trans people, the flipside of that argument is that most people’s gender is indeed innate, as social conservatives have always thought. Why? Because, according to trans activism, most people are ‘cis’ - they ‘identify’ as the gender they were born into. If 1% are trans, then 99% are cis; perhaps being trans is more common, especially if it includes the non-binary category, but still the vast majority of people are cis. So, since most people born with female reproductive systems are ‘cis’ women, they are supposedly innately feminine, which is to say, innately submissive, subordinate, and servile. Meanwhile a similar proportion of people born with male reproductive systems are considered to be ‘cis’ men: innately masculine, and therefore born into a socially dominant role. It is likely that many activists and well-meaning people on the sidelines of this debate have not thought it through far enough to understand that this is the logical and necessary conclusion of their arguments.

While most trans activists avoid definitions like the plague, such a conclusion is borne out by the attempts of some to redefine ‘woman’ and ‘female’. Definitions of ‘woman’ include such gems as: “a person who acts in accordance with traditional gender roles assigned to the female sex” and “anyone that culturally identifies and presents as the combination of stereotypes and cultural norms we define as feminine” or “adhering to social norms of femininity, such as being nurturing, caring, social, emotional, vulnerable and concerned with appearance”. And femaleness is “a universal sex defined by self-negation … I’ll define as female any psychic operation in which the self is sacrificed to make room for the desires of another … [The] barest essentials [of femaleness are] an open mouth, an expectant asshole, blank, blank eyes.”13

This is what we are fighting. It is why we are fighting. We refuse to submit.

8 notes

·

View notes

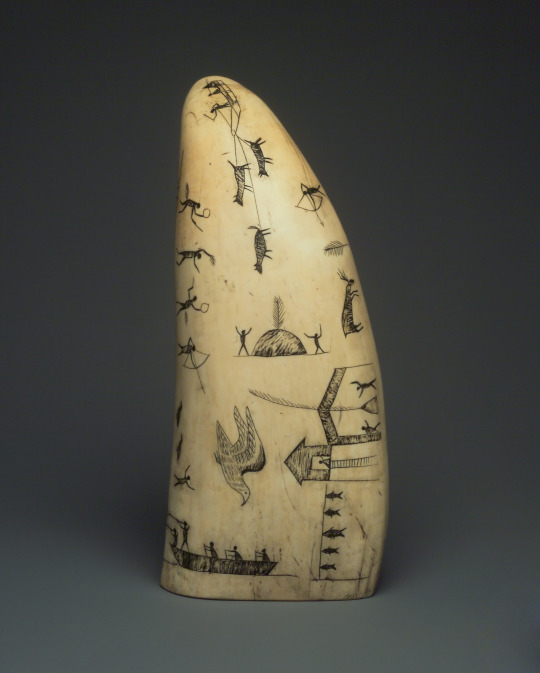

Photo

Upcoming 2020 Exhibitions

We’re pleased to announce a selection of upcoming 2020 exhibitions. This winter, we welcome back our iconic Kehinde Wiley painting Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps (2005), which for the first time at the Brooklyn Museum will be presented in dialogue with its early nineteenth-century source painting, Jacques-Louis David’s Bonaparte Crossing the Alps (1801). We also look at our collection from new perspectives with focused exhibitions that present historical works through a contemporary, multifaceted lens. Out of Place: A Feminist Look at the Collection examines nearly 50 collection works using an intersectional feminist framework. Climate in Crisis: Environmental Change in the Indigenous Americas is an installation of the Museum’s Arts of the Americas collection which reconsiders indigenous art from the perspective of the prolonged and ongoing impact of climate change and colonization. Contemporary artist and MacArthur Fellowship recipient Jeffrey Gibson mines our collection and archives to examine collecting practices and reinterpret historical representations of indigenous communities. We also present African Arts—Global Conversations, a cross-cultural exhibition pairing diverse African works with collection objects made around the world, and Striking Power: Iconoclasm in Ancient Egypt, which examines the damage to sculptures and reliefs in ancient Egypt as a way of also exploring twenty-first-century concerns and struggles over public monuments and the destruction of antiquities.

In March, we celebrate the iconic history and trailblazing aesthetics of Studio 54 in a special exhibition featuring never-before-seen archival materials, video, photography, fashion, and more. We will also present the first solo museum exhibition dedicated to Brooklyn-based photographer John Edmonds, winner of our inaugural UOVO Prize for an emerging Brooklyn artist. And in the fall of 2020, we are proud to mount the first career retrospective of the work of Lorraine O’Grady, one of the most significant figures in contemporary performance, conceptual, and feminist art.

“We’re thrilled to present a roster of exhibitions next season that are in conversation with our collection in fresh and exciting ways,” says Anne Pasternak, Shelby White and Leon Levy Director, Brooklyn Museum. “As an encyclopedic museum, we’re always looking for new ways to examine our collection and open it up to include narratives that have historically been left out of the canon. In 2020, we’re committed to exhibitions that do just that: telling stories that are rarely told, through the eyes of contemporary artists.”

Jacques-Louis David Meets Kehinde Wiley

January 24–May 10, 2020

Morris A. and Meyer Schapiro Wing, 4th Floor