#iwanami hall

Text

AKIKO あるダンサーの肖像

エキプ・ド・シネマ第65回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.72

岩波ホール

監督:羽田澄子/出演:アキコ・カンダ

#AKIKO あるダンサーの肖像#AKIKO#エキプ・ド・シネマ#EQUIPE DE CINEMA#Iwanami Hall#岩波ホール#sumiko haneda#羽田澄子#akiko kanda#アキコ・カンダ#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

MOANA with Sound

Robert J. Flaherty, Frances H. Flaherty, Monica Flaherty

モアナ 南海の歓喜

ロバート・フラハティ

https://moana-sound.com

https://www.iwanami-hall.com

http://japandocs.org/dn6/

0 notes

Text

This piece was originally written for the Asahi Shinbun newspaper, and published in the evening edition, on 13 May, 1977. It was reproduced, with the addition of the photo of Kurosawa and Tarkovsky in Solaris pamphlet. It was also published in Nihonkai Eigasha, June 1978. It was again published in Image Forum No. 80, March special issue, 1987, under a different title: Solaris: A Nostalgy toward Nature on Great Earth. Finally, the article appeared in The Complete Akira Kurosawa, Vol 6, Iwanami Shoten Publishers, Tokyo, 1988, with the original title, Tarkovsky and Solaris. The article was translated for Nostalghia.com by their Japan correspondent Sato Kimitoshi.

"Tarkovsky and Solaris" by Akira Kurosawa

I met Tarkovsky for the first time when I attended my welcome luncheon at the Mosfilm during my first visit to Soviet Russia. He was small, thin, looked a little frail, and at the same time exceptionally intelligent, and unusually shrewd and sensitive. I thought he somehow resembled Toru Takemitsu, but I don’t know why. Then he excused himself saying, “I still have work to do,” and disappeared, and after a while I heard such a big explosion as to make all the glass windows of the dining hall tremble hard. Seeing me taken aback, the boss of the Mosfilm said with a meaningful smile: “You know another world war does not break out. Tarkovsky just launched a rocket. This work with Tarkovsky, however, has proved a Great War for me.” That was the way I knew Tarkovsky was shooting Solaris.

After the luncheon party, I visited his set for Solaris. There it was. I saw a burnt down rocket was there at the corner of the space station set. I am sorry I forgot to ask him as to how he had shot the launching of the rocket on the set. The set of the satellite base was beautifully made at a huge cost, for it was all made up of thick duralumin.

It glittered in its cold metallic silver light, and I found light rays of red, or blue or green delicately winking or waving from electric light bulbs buried in the gagues on the equipment lined up in there. And above on the ceiling of the corridor ran two duralumin rails from which hanged a small wheel of a camera which could move around freely inside the satellite base.

Tarkovsky guided me around the set, explaining to me as cheerfully as a young boy who is given a golden opportunity to show someone his favorite toybox. Bondarchuk, who came with me, asked him about the cost of the set, and left his eyes wide open when Tarkovsky answered it. The cost was so huge: about six hundred million yen as to make Bondarchuk, who directed that grand spectacle of a movie “War and Peace,” agape in wonder.

Now I came to fully realize why the boss of the Mosfilm said it was “a Great War for me.” But it takes a huge talent and effort to spend such a huge cost. Thinking “This is a tremendous task” I closely gazed at his back when he was leading me around the set in enthusiasm.

Concerning Solaris, I find many people complaining that it is too long, but I do not think so. They especially find too lengthy the description of nature in the introductory scenes, but these layers of memory of farewell to this earthly nature submerge themselves deep below the bottom of the story after the main character has been sent in a rocket into the satellite station base in the universe, and they almost torture the soul of the viewer like a kind of irresistible nostalghia toward mother earth nature, which resembles homesickness. Without the presence of beautiful nature sequences on earth as a long introduction, you could not make the audience directly conceive the sense of having-no-way-out harboured by the people “jailed” inside the satellite base.

I saw this film late at night in a preview room in Moscow for the first time, and soon I felt my heart aching in agony with a longing to returning to the earth as quickly as possible. Marvellous progress in science we have been enjoying, but where will it lead humanity after all? Sheer fearful emotion this film succeeds in conjuring up in our soul. Without it, a science fiction movie would be nothing more than a petty fancy.

These thoughts came and went while I was gazing at the screen.

Tarkovsky was together with me then. He was at the corner of the studio. When the film was over, he stood up, looking at me as if he felt timid. I said to him, “Very good. It makes me feel real fear.” Tarkovsky smiled shyly, but happily. And we toasted vodka at the restaurant in the Film Institute. Tarkovsky, who didn’t drink usually, drank a lot of vodka, and went so far as to turn off the speaker from which music had floated into the restaurant, and began to sing the theme of samurai from Seven Samurai at the top of his voice.

As if to rival him, I joined in.

For I was at that moment very happy to find myself living on Earth.

Solaris makes a viewer feel this, and even this single fact shows us that Solaris is no ordinary SF film. It truly somehow provokes pure horror in our soul. And it is under the total grip of the deep insights of Tarkovsky.

There must be many, many things still unknown to humanity in this world: the abyss of the cosmos which a man had to look into, strange visitors in the satellite base, time running in reverse, from death to life, strangely moving sense of levitation, his home which is in the mind of the main character in the satellite station is wet and soaked with water. It seems to me to be sweat and tears that in his heartbreaking agony he sqeezed out of his whole being. And what makes us shudder is the shot of the location of Akasakamitsuke, Tokyo, Japan. By a skillful use of mirrors, he turned flows of head lights and tail lamps of cars, multiplied and amplified, into a vintage image of the future city. Every shot of Solaris bears witness to the almost dazzling talents inherent in Tarkovsky.

Many people grumble that Tarkovsky’s films are difficult, but I don’t think so. His films just show how extraordinarily sensitive Tarkovsky is. He made a film titled Mirror after Solaris. Mirror deals with his cherished memories in his childhood, and many people say again it is disturbingly difficult. Yes, at a glance, it seems to have no rational development in its storytelling. But we have to remember: it is impossible that in our soul our childhood memories should arrange themselves in a static, logical sequence.

A strange train of fragments of early memory images shattered and broken can bring about the poetry in our infancy. Once you are convinced of its truthfulness, you may find Mirror the easiest film to understand. But Tarkovsky remains silent, without saying things like that at all. His very attitude makes me believe that he has wonderful potentials in his future.

There can be no bright future for those who are ready to explain everything about their own film. —Akira Kurosawa.

9 notes

·

View notes

Link

Artist: Yasumasa Morimura

Venue: Hara Museum, Tokyo

Exhibition Title: Yasumasa Morimura: Ego Obscura, Tokyo 2020

Date: January 25 – June 7, 2020

Click here to view slideshow

Full gallery of images, press release and link available after the jump.

Images:

Images courtesy of the artist and Hara Museum, Tokyo. Photos by Keizo Kioku.

Press Release:

No matter how deeply I searched within myself, I could never find anything resembling a center, much less any kind of truth. From the time I was a child, the only thing I knew for sure was that there was a vast emptiness there. If anything, things like truth, values and ideas, existed outside my body, and like clothes, I was free to change them whenever I liked. This concept made a lot more sense to me than anything else.

from Ego Obscura

The Hara Museum of Contemporary Art is proud to present Yasumasa Morimura: Ego Obscura, Tokyo 2020. In his acclaimed photographic self-portraits, Morimura re-enacts famous paintings, movies and moments in history, injecting himself as the protagonist. By reincarnating himself through the skillful use of makeup and costume, he transcends the time, race and gender of the subject while imbuing it with a meta-commentary uniquely his own. Making a splash in 1985 with his debut work Portrait (Van Gogh), Morimura has persistently explored the theme of the “self” through his photographic works, and more recently through self-produced, -scripted and -acted video works and live performances.

This exhibition comes on the heels of Morimura’s highly successful Yasumasa Morimura: Ego Obscura held last year at the Japan Society in New York. For this Tokyo version, he has rearranged his video work entitled Ego Obscura, which, along with a lecture performance, comprises the centerpiece of the show. In the video, Morimura appears as Emperor Hirohito, General Douglas MacArthur, Marilyn Monroe and Yukio Mishima – iconic figures that are deeply etched into the collective memory of the Japanese people. Born in Osaka in 1951 during the post-war occupation by the Allied Forces, Morimura was educated at a time when the country’s pre-war teachings had been rejected and the resulting “void” infiltrated by Western values. This experience led him to see truth, values and ideas as things that “reside outside the body,” which like clothes could be “freely changed” at will (quoted from Ego Obscura).[1]

For over 30 years, Morimura has injected himself into the history of Western art. What ideas did he embrace as he went beyond notions of race and gender? Those ideas, which form the background from which his works were born, are given voice in the exhibition’s titular video work Ego Obscura, which engendered a strong response in New York. They are encompassed in the title “Ego Obscura,” an unfamiliar word that Morimura uses to refer to what he describes as “an ambiguous ego wrapped in darkness.” In 2020, the year of the Tokyo Olympics fifty-five years after the first Olympics which symbolized the country’s postwar revival, in self-portraits imbued with complex feelings towards a motherland that go beyond mere affection, Morimura directs the question “what is the “self” ?” not only to us, but to the nation of Japan itself as well.

Highlights of the Exhibition

1. Ego Obscura, Tokyo 2020 Lecture Performance

Morimura will give a lecture performance of his work Ego Obscura, Tokyo 2020.

Dates: January 25 (Sat.), 26 (Sun.), February 22 (Sat.), 23 (Sun.), March 20 (Friday/national holiday), 21 (Sat.), April 12 (Sun.)

Time: 16:00 – 17:00

*Performance will be held in Japanese only.

*Reservations required. Free with museum admission. Details will be posted on the museum website.

2. Yasumasa Morimura and the Hara Museum

Morimura’s previous exhibitions at the Hara Museum include Rembrandt’s Room (1994), which delves deeply into the “self” using as his theme the great 17th century painter from the Netherlands and the light and dark aspects of his life, and Morimura Self-Portraits: An Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo (2001), which presents the life, loves and death of the great 20th-century Mexican artist Frida Kahlo through festively rendered images. Another work, Rondo, is a unique permanent installation that Morimura made using one of the building’s toilets in 1994. While undergoing occasional changes in clothing, Rondo stands as one of the museum’s defining trademarks.

3. Morimura to Juxtapose His Famous Early Work Portrait (Futago) born of Manet’s Olympia with His New Work Une moderne Olympia 2018

Morimura’s famous Portrait (Futago) (1988) which he created early in his career, takes as its subject Edouard Manet’s Olympia (1865), a work that changed the course of modern painting. In it, Morimura, a person of the so-called “yellow race” and of the male gender, assumes the roles of both the white prostitute and black servant painted by Manet. Now, thirty years later, Morimura has unveiled his most recent work, Une moderne Olympia 2018, in which the figure whose nakedness is exposed to the public gaze looks back with a gaze even more intense. Here, the young prostitute has been changed into a geisha reminiscent of Madame Butterfly and the black servant into a Western male reminiscent of Pinkerton. The exhibition features a new work by Morimura based on Manet’s other masterpiece made late in his career, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. We invite you to view Morimura’s presentation of these various protagonists and the complex interaction that arises between them.

Yasumasa Morimura

Born 1951 in Osaka, where he continues to live and work. Completed undergraduate and graduate degrees at Kyoto City University of Arts. He made his debut in 1985 with self-portrait works based on his personal interpretation of Vincent Van Gogh. He has since produced a number of self-portraits in elaborated staged photographic and video works, with himself incarnated as art-historical images, famous film actresses and iconic figures from the 20th century.

In 1988, Morimura was invited to take part in the Aperto section of the 43rd Venice Biennale. In the years since, he has participated in countless important exhibitions both in Japan and abroad. He draws his main themes from famous paintings by such iconic artists as Van Gogh, Velázquez, Goya, Vermeer and Frida Kahlo, as well as images from movies and other forms of pop culture and mass media, as seen in his Requiem series. Not only does he grapple with the issues of identity and gender in these images, Morimura uses them as meta-commentaries that posit questions to himself and to his audience, about the role of painting and photography as forms of media.

His solo exhibitions include The Sickness unto Beauty: Self-portrait as Actress (Yokohama Museum of Art, Yokohama, 1996), Self-Portrait as Art History (Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo and two other venues, 1998), Morimura Self-Portraits: An Inner Dialogue with Frida Kahlo (Hara Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, 2001), A Requiem: Art on Top of the Battlefield (Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Tokyo and other venues, 2010), Yasumasa Morimura: Theater of the Self (The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, 2013), The Self-Portraits of YASUMASA MORIMURA: My Art, My Story, My Art History (National Museum of Art, Osaka, 2016), Yasumasa Morimura. The history of the self-portrait (The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, 2017) and Yasumasa Morimura: Ego Obscura (Japan Society, New York, 2018).

In 2014, he was the artistic director of Yokohama Triennale.

In 2018, Morimura performed Yasumasa Morimura: Nippon Cha Cha Cha! at the Pompidou Metz (Metz, France), Minato City Gender Equality Center’s Libra Hall (Tokyo) and the Japan Society (New York).

In 2018, the Morimura @ Museum was opened in Kitakagaya, Osaka.

His publications include Self-Portrait as Actress: Yasumasa Morimura, Nigensha Co., Ltd, 2010; Manebu Art History (imitating art history), Akaaka Art Publishing Inc., 2010; Taidan Nanimonokaheno Requiem/20 Seiki wo Shikosuru (conversations about requiem/considering the 20th century), Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 2011; Bijutsu, Otoseyo (art, respond!), Chikumashobo Ltd., 2014 and Jigazo no Yukue (the whereabouts of self-portrait), Kobunsha Co., Ltd., 2019.

He has received a number of awards for his achievements, including the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology’s Art Encouragement Prize of Fine Arts (2007), 52th Mainichi Art Prize (2011), Photographic Society of Japan Award (2011) and also one of the most prestigious awards in the field of art and science, the Order of Purple Ribbon (2011).

Link: Yasumasa Morimura at Hara Museum

from Contemporary Art Daily https://bit.ly/2Wq4Utl

0 notes

Text

ローザ・ルクセンブルク

エキプ・ド・シネマ第79回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.86

岩波ホール

監督・脚本:マルガレーテ・フォン・トロッタ/出演:バルバラ・スコヴァ ほか

#rosa luxemburg#ローザ・ルクセンブルク#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#Margarethe von Trotta#マルガレーテ・フォン・トロッタ#barbara sukowa#バルバラ・スコヴァ#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

三人姉妹

エキプ・ド・シネマ15周年記念作品

エキプ・ド・シネマ第86回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.93

岩波ホール

監督・脚本:マルガレーテ・フォン・トロッタ/出演:ファニー・アルダン、グレタ・スカッキ、ヴァレリア・ゴリノ ほか

#Paura e Amore#三人姉妹#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#Margarethe von Trotta#マルガレーテ・フォン・トロッタ#fanny ardant#ファニー・アルダン#greta scacchi#グレタ・スカッキ#valeria golino#ヴァレリア・ゴリノ#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

夕映えの道

エキプ・ド・シネマ第138回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.145

岩波ホール

監督・脚本:ルネ・フェレ/出演:ドミニク・マルカス、マリオン・エルド ほか

#RUE DU RETRAIT#夕映えの道#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#Rene Feret#ルネ・フェレ#Dominique Marcas#ドミニク・マルカス#Marion Held#マリオン・エルド#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

ムアンとリット

エキプ・ド・シネマ第109回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.116

岩波ホール

監督:チャート・ソンスィー/出演:チンタラー・スッカパット、サンティスック・プロムシリ ほか

#MUEN AND RID#ムアンとリット#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#Cherd Songsri#チャート・ソンスィー#Jintara Sookapat#チンタラー・スッカパット#Santisook Promsiri#サンティスック・プロムシリ#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

ハンナ・アーレント

エキプ・ド・シネマ第190回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.196

岩波ホール

監督:マルガレーテ・フォン・トロッタ/出演:バルバラ・スコヴァ、アクセル・ミルベルク ほか

#hannah arendt#ハンナ・アーレント#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#Margarethe von Trotta#マルガレーテ・フォン・トロッタ#barbara sukowa#バルバラ・スコヴァ#axel milberg#アクセル・ミルベルク#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

冬の小鳥

エキプ・ド・シネマ第171回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.178

岩波ホール

監督:ウニー・ルコント/出演:キム・セロン ほか

#Une Vie Toute Neuve#冬の小鳥#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#Ounie Lecomte#ウニー・ルコント#Kim Saeron#Kim Sae-ron#キム・セロン#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

山の郵便配達

エキプ・ド・シネマ第128回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.135

岩波ホール

監督:フォ・ジェンチイ/出演:トン・ルゥジュン、リィウ・イェ、ジャオ・シィウリ、ゴォン・イエハン、チェン・ハオ ほか

#那山 那人 那狗#POSTMEN IN THE MOUNTAINS#山の郵便配達#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#Huo Jianqi#霍建起#フォ・ジェンチイ#Teng Rujun#トン・ルゥジュン#Liu Ye#リィウ・イェ#Zhao Xiuli#ジャオ・シィウリ#Gong Yehang#ゴォン・イエハン#Chen Hao#チェン・ハオ#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

阿片戦争

岩波ホール創立30周年記念第1弾

エキプ・ド・シネマ第118回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.125

岩波ホール

監督:謝晋

#鴉片戦争#THE OPIUM WAR#阿片戦争#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#Xie Jin#シェ・チン#謝晋#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

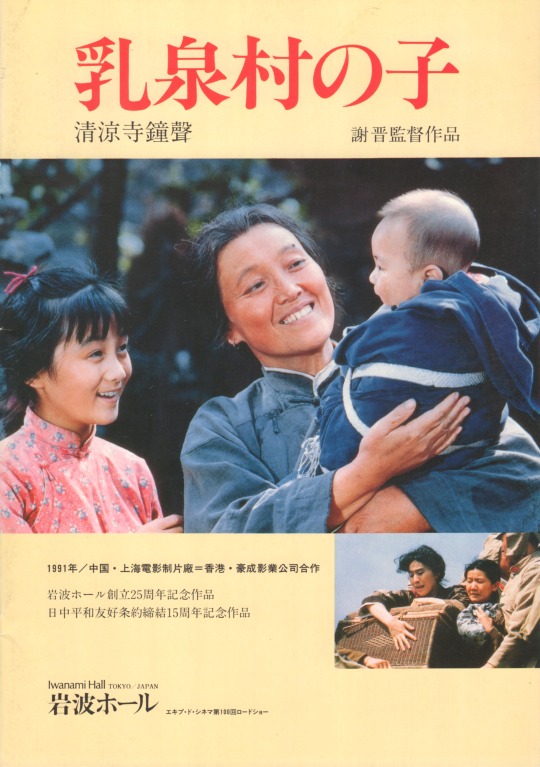

乳泉村の子

エキプ・ド・シネマ第100回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.107

岩波ホール

監督:シェ・チン/出演:ティン・イー、栗原小巻、プー・ツンシン、ヨウ・ヨン、リー・ティン、川田あつ子 ほか

#清涼寺鐘聲#THE BELL OF THE QING LIANG TEMPLE#乳泉村の子#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#Xie Jin#謝晋#シェ・チン#ding yi#ティン・イー#栗原小巻#Pu Cun-Xin#プー・ツンシン#You Yong#ヨウ・ヨン#Li Ting#リー・ティン#川田あつ子#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

オレンジと太陽

エキプ・ド・シネマ第180回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.187

岩波ホール

監督:ジム・ローチ/出演:エミリー・ワトソン、デビッド・ウェナム、ヒューゴ・ウィーヴィング ほか

#Oranges and Sunshine#オレンジと太陽#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#Jim Loach#ジム・ローチ#emily watson#エミリー・ワトソン#david wenham#デビッド・ウェナム#hugo weaving#ヒューゴ・ウィーヴィング#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

0 notes

Text

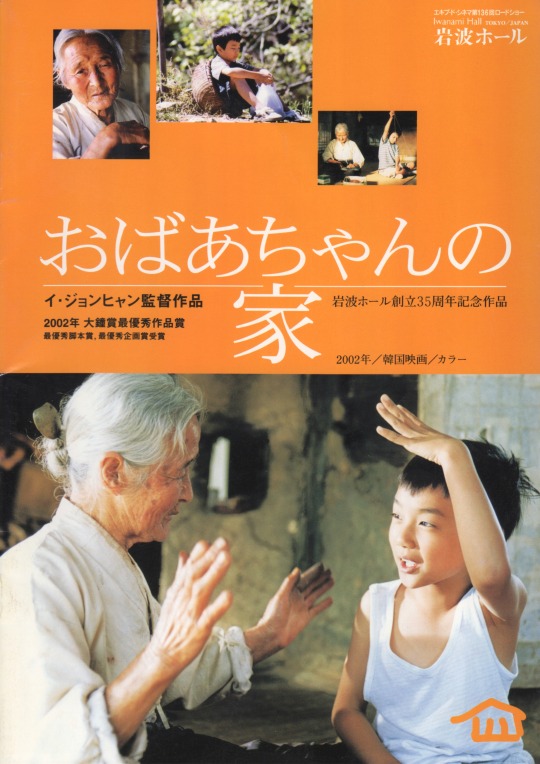

おばあちゃんの家

岩波ホール創立35周年記念作品

エキプ・ド・シネマ第136回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.143

岩波ホール

監督:イ・ジョンヒャン/出演:キム・ウルブン、ユ・スンホ ほか

#the way home#おばあちゃんの家#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#LEE Jeong-Hyang#イ・ジョンヒャン#KIM Eul-Boon#キム・ウルブン#YOO Seung-Ho#ユ・スンホ#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

1 note

·

View note

Text

アントニア

エキプ・ド・シネマ第116回ロードショー

EQUIPE DE CINEMA No.123

岩波ホール

監督:マルレーン・ゴリス/出演:ヴィレケ・ファン・アメローイ ほか

#ANTONIA#アントニア#エキプ・ド・シネマ#equipe de cinema#iwanami hall#岩波ホール#marleen gorris#マルレーン・ゴリス#Willeke Van Ammelrooy#ヴィレケ・ファン・アメローイ#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#映画パンフレット#movie pamphlet

1 note

·

View note