#james c. wasson

Photo

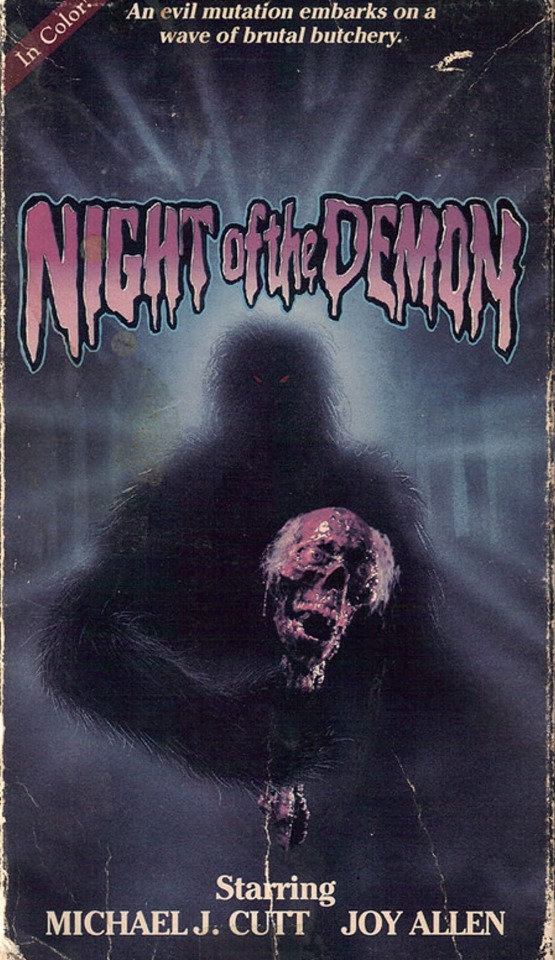

Night of the Demon (1980) // dir. James C. Wasson

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Night of the Demon (1980)

"Now, Bigfoot's not playing games anymore. Maybe next time he won't be happy just to scare us."

#night of the demon#blood tw#horror imagery tw#video nasty#james c. wasson#mike williams#jim l. ball#michael cutt#jody lazarus#bob collins#melanie graham#shannon cooper#paul kelleher#william f. nugent#lynn eastman rossi#eugene dow#don hurst#terry wilson#jennifer west#joy allen#really quite dreadful but bizarrely compelling. shot in 79‚ shown at a few festivals in 80 and then spliced full of gory inserts without#the director's knowledge and released on video‚ where it promptly became a fabled nasty. it starts as a surprising slowburn so that i#wondered if it deserved its reputation‚ but by the time a random biker got his dick torn off I'd pretty much settled on 'yeah ok of course#this got banned'. poor performances and some sketchy fx aren't helped by the fact that the director was forced to adopt a single take#policy‚ and the post production tinkering didn't help the pacing. it's very difficult to imagine exactly what this film was before those#splatter inserts. an hour and change of six people wandering around the countryside i guess. also the film commits the cardinal sin of#setting everything as flashback‚ immediately revealing who will live and die (a weirdly common trope in indie slashers‚ and p much always a#mistake). tasteless and trashy and honestly fairly bad but it's an interesting footnote in horror history and the bts scenes tales make for#fascinating reading. director and producer wanted Tab Hunter for the lead (he wisely turned it down) and oh how I'd love to see that film#at least it's another nasty i can knock off the to watch list

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Viddying the Nasties | Night of the Demon (Wasson, 1980)

This review contains mild spoilers.

While I take my October / Halloween / Spooky Season / [insert scary sounding pun] viewing very seriously, most years I don’t do a whole lot of planning outside of a few titles in terms of what I intend to watch. This year especially my intention to get through the embarrassingly large stack of unwatched movies on my shelf were completely sidetracked when the fine folks at the Criterion Channel decided to do a series on ‘80s horror, and further undermined when I made a trip to the video store (apparently it was Video Store Day this past weekend). What I’m getting at is, if there are themes coming up in my viewing, they were not pre-planned, and it turns out that for some reason or another, I’ve watched a greater number than Bigfoot-centric movies this month than usual (usual being zero). Of course, The Legend of Boggy Creek is the obvious classic, and I have no great insights into that movie aside from that it’s not exactly what I look for in a horror. And there was The Geek, the Bigfoot porno from an unknown director that was released by Vinegar Syndrome as part of one of their box sets. And there’s this one. And I think these last two are worth comparing. In The Geek, the climax involves Bigfoot giving his dick to people in a couple of sex scenes of varying degrees of consent. In this, there’s a scene where Bigfoot does not give his dick to people, but in fact tears the dick off one of his victims, with the before and gruesome after captured in extremely blunt close-ups. As the saying goes, the Bigfoot giveth and the Bigfoot taketh away.

But putting aside my characteristically long-winded setup for that line, I think there’s something there to the movie’s approach to violence. This was notable for being one of the Video Nasties, and I think this is the kind of movie I expected them to be like when I first started exploring years ago. The violence is presented so bluntly that it basically overpowers the other qualities of the movie. Watching the special features on the Severin blu-ray, I was a little surprised to learn that much of the gore was shot later on without the director’s involvement because of a test screen where the movie was received as an unintentional comedy. But maybe that makes a certain amount of sense, as the sheer brutality of the violence has a certain form-shattering quality, puncturing through what’s otherwise a moody, low key wilderness piece.

It also accents the narrative pretty interestingly in a couple of ways. There’s the fact that much of the violence is directed towards men in vulnerable states. There’s the aforementioned dick-ripping scene, where a character goes to relieve himself in the woods, and a few scenes where characters are having heterosexual sex, but it’s the male who gets attacked or killed by Bigfoot in both cases. I’m not sure the filmmakers intended to comment on the gendered nature of violence in the genre, but it does stand out from the blunt sexualized quality of many slashers of the era. I also find it interesting how much of the violence is told via flashback. This is probably the result of filming these scenes after the initial shoot, but when you think of how the element of hearsay around urban legends, it does call the veracity of these incidents into question. (Not that it reduces their visceral impact.)

Which I think ties into what this movie is ultimately about, which is the way the characters’ overconfidence in their belief systems undermine their understanding of the situation. The protagonists are scientists who are perhaps too prone to confirmation bias, like a scene where they destructively interrupt what looks like an esoteric religious ritual because of the way they interpret the scene. (One characters’ nonchalance that he effectively started a forest fire stands in contrast to his supposed scientific values.) And then we start to learn more behind the legend, and it’s revealed character who everyone assumed was driven crazy about giving birth to a deformed child was actually abused by her father, who interpreted the tragic events that happened to her through his extreme religious views, taking each event as a sign for further cruelty. I don’t know if the movie set out to make a point around these subjects, but I do think there’s a deep sense of empathy for this character.

And ultimately I find this a really effective horror film, with its mix of unhinged violence and low key forest atmosphere. I probably bring this up every few reviews, but there’s a certain quality you get when you go out and shoot a low budget production in the middle of the woods that really enhances the sense of horror for me. (I should note that I’m a lifelong city slicker.) And the climax, where the characters are trapped in a cabin and dispatched mercilessly, has a certain bleakness that got under my skin. What they thought was a refuge ends up being a trap in its claustrophobic smallness, and whatever defenses these characters believed their knowledge gave them collapse in the face of such brutality. There’s no escape from the Bigfoot.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This Friday-Sunday (October 7th-9th, 2021) at the Carolina Theatre of Durham, it’s their semi-annual SPLATTERFLIX weekend!

It’s exactly what you think it is: the goriest, scariest horror movies ever made, re-animated by Retro Film Series for screening over a three-day weekend.

Featuring:

Lewis Teague’s Alligator (1980)

Ken Russell’s Altered States (1980)

Paul Morrissey’s Blood for Dracula: Uncut Version (1974)

Joe Dante’s The ‘Burbs (1989)

Tony Maylam’s The Burning (1981)

George Romero’s The Crazies (1970)

Douglas McKeown’s The Deadly Spawn (1983)

Steven Spielberg’s Duel (1970)

Paul Morrissey’s Flesh for Frankenstein: Uncut Version (1973)

Kenny Ortega’s Hocus Pocus (1993)

Neil Jordan’s Interview with the Vampire (1994)

Stephen Chiodo’s Killer Klowns from Outer Space (1988)

James C. Wasson’s Night of the Demon (1980)

Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

Ron Underwood’s Tremors (1990)

David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983)

Tickets are $10.00 each, or you can get a 10-pack for $80. Check here for schedule.

“Along with the City of Durham, we have made major investments in the Carolina Theatre for the comfort and safety of our guests during our closure,” says Randy McKay, the Carolina Theatre’s President & CEO. “That includes tens of thousands of dollars in new state of the art HVAC upgrades from Global Plasma Solutions (GPS) that remove biohazards, pollen, and other contaminants to make our air as pure — and sometimes purer — than outdoor air.” The theater has also earned a Global Biorisk Advisory Council® (GBAC) STAR™ accreditation for its cleaning practices to ensure that guests have a safe and enjoyable experience. “Together, these cleaning practices and advanced air filtration make the Carolina Theatre one of the safest spaces to attend a film or live event in the region,” says McKay. [source]

Carolina Theatre of Durham

309 W. Morgan St., Durham, NC

http://www.carolinatheatre.org/

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET 3: DREAM WARRIORS (1987) – Episode 224 – Decades Of Horror 1980s

“Welcome to prime time, bitch!” Not words I’d use in front of my mother, but they are iconic just the same. Join your faithful Grue-Crew – Chad Hunt, Bill Mulligan, Crystal Cleveland, and Jeff Mohr, along with guest host Ralph Miller – as they enter another Wes Craven nightmare, A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987). Expect a lot of FX talk with Ralph in the house!

Decades of Horror 1980s

Episode 224 – A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel!

Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content!

https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

A psychiatrist familiar with knife-wielding dream demon Freddy Krueger helps teens at a mental hospital battle the killer who is invading their dreams.

[NOTE: Effects crew credits are listed as they appear in the film credits.]

Director: Chuck Russell

Writers: Wes Craven (story) (screenplay) (characters); Bruce Wagner (story) (screenplay); Frank Darabont (screenplay); Chuck Russell (screenplay)

Music: Angelo Badalamenti

Storyboard Artist / Visual Consultant: Peter von Sholly

Stop-Motion Skeleton and Marionette Effects: Doug Beswick Productions, Inc.

Stop-Motion Animation: Doug Beswick

Effects Photography Supervisor: Jim Aupperle

Stop-Motion Puppet Construction: Yancy Calzada

Marionette Construction: Mark Bryan Wilson (as Mark Wilson)

Miniatures: James Belohovek

Illustrator: Larry Nikolai

Makeup effects Sequences: Greg Cannom

Assistants to Greg Cannom: Larry Odien, Earl Ellis, John Vulich, Keith Edmier, Brent Baker

Krueger Makeup effects: Kevin Yagher

Assistants to Kevin Yagher: Jim Kagel, Mitch DeVane, Gino Crognale, Brian Penikas, David Kindlon, Steve James, Everett Burrell

Makeup Effects Sequences: Mark Shostrom

Assistants to Mr. Shostrum: Robert Kurtzman, Bryant Tausek, John Blake Dutro, James McLoughlin (as Jim McLoughlin), Cathy Carpenter

Additional Makeup Effects: Matthew W. Mungle (as Mathew Mungel)

Assistant to Mathew Mungel: Russell Seifert

Mechanical Effects: Image Engineering

Special Effects Coordinator: Peter Chesney

Lead Technician: Lenny Dalrymple

Mechanical Designers: Bruce D. Hayes (as Bruce Hayes), Joe Starr, Anton Tremblay (as Tony Tremblay)

Effects Technicians: Bernardo F. Munoz (as Bernard Munoz), Rod Schumacher, Bob Ahmanson

Effects Crew: Scott Nesselrode, Tom Chesney, Kelly Mann, Phillip Hartmann (as Phillip Hartman), Ralph Miller III (as Ralph Miller), Joel Fletcher, Brian Mcfadden, Sandra Stewart (as Sandy Stewart), Terry Mack (as Troy Mack), Blaine Converse, Ron MacInnes, Brendan C. Quigley

Selected Cast:

Heather Langenkamp as Nancy Thompson

Craig Wasson as Dr. Neil Gordon

Patricia Arquette as Kristen Parker

Ken Sagoes as Roland Kincaid

Ira Heiden as Will Stanton

Rodney Eastman as Joey Crusel

Jennifer Rubin as Taryn White

Penelope Sudrow as Jennifer Caulfield

Bradley Gregg as Phillip Anderson

Laurence Fishburne as Max Daniels (credited as Larry Fishburne)

John Saxon as Donald Thompson

Priscilla Pointer as Dr. Elizabeth Simms

Clayton Landey as Lorenzo

Brooke Bundy as Elaine Parker

Nan Martin as Sister Mary Helena

Stacey Alden as Nurse Marcie

Dick Cavett as Himself

Zsa Zsa Gabor as Herself

Paul Kent as Dr. Carver

Guest host Ralph Miller III, who worked behind the scenes on Dream Warriors provides insights and many effects development photos that are shown in the YouTube version of the podcast. Post-recording, the crew wants to clarify that Kevin Yagher was responsible for the Freddy Snake, and Mark Shostrom was in charge of the Penelope Sudrow dummy that smashes into the Freddyvision TV.

With the success of A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987), following the critical failure of A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985), New line Cinema firmly cemented Freddy Krueger and A Nightmare on Elm Street as one of the most iconic horror franchises of its time. Not only does Dream Warriors feature Robert Englund continuing to breathe both humor and fear into Freddy Krueger but also the return of both Heather Langenkamp and John Saxon from the original. The film also features Craig Wasson (Ghost Story) as the male lead and early film roles for Patricia Arquette and Larry Fishburne. Frank Darabont (The Mist) and Bruce Wagner join Wes Craven on scripting chores and Chuck Russell (The Blob, The Mask) directs while Angelo Badalamenti (Twin Peaks, Blue Velvet) provides the score – a winning combination of talent. Surely a Grue-Crew highly recommended selection with special effects by Greg Cannom, Doug Beswick, Mark Shostrom, Kevin Yagher, and more!

Be sure to check out the first time the 80s Grue-Crew took a dive into this film in February 2017, featuring Doc Rotten, Christopher G. Moore, and Thomas Mariani as the Grue-Crew. You can find it here: A NIGHTMARE ON ELMS STREET 3: DREAM WARRIORS (1987) — Episode 102

Every two weeks, Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror 1980s podcast will cover another horror film from the 1980s. The next episode’s film, chosen by Jeff, will be The Changeling (1980), starring George C. Scott, Trish Van Devere, Melvyn Douglas, . . . and a bouncing, red, rubber ball.

Please let them know how they’re doing! They want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans – so leave them a message or comment on the gruesome Magazine Youtube channel, on the website, or email the Decades of Horror 1980s podcast hosts at [email protected].

Check out this episode!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books Read in 2022

1. A Court of Silver Flames- Sarah J. Maas

2. Told After Supper- Jerome K. Jerome

3. The Crazy Ladies of Pearl Street- Trevanian

4. To Kill a Kingdom- Alexandra Christo

5. The Father Christmas Letter- J.R.R. Tolkien

6. The Book of Doing and Being- Barnett Bain

7. The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August- Claire North

8. Northern Lights (Golden Compass)- Philip Pullman

9. The Subtle Knife- Phillip Pullman

10. The Amber Spyglass-Phillip Pullman

11. The Skincare Bible- Anjali Mahto

12. The Popular Culture Reader- John L. Nachbar Wright Jack, & Deborah Weiser

13. Another Roadside Attraction- Tom Robbins

14. Angels and Demons- Dan Brown

15. The Da Vinci Code- Dan Brown

16. The Vintage Tea Cup Club- Vanessa Greene

17. A Woman of Independent Means- Elizabeth Forsythe Hailey

18. The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart- Holly Ringland

19. Humankind: A Hopeful History- Rutger Bergman

20. Goddess- Kelly Gardi

21. Wild Animals I Have Known- Ernest Thompson Seton

22. Femme Fatale: Cinema’s Most Unforgettable Lethal Ladies- Dominique Manon and James Ursini

23. Crazy for the Storm- Norman Ollestad

24. The Power of Body Language: How to Succeed in Every Business and Social Encounter- Tonya Reiman

25. The Wolves of Willoughby Chase - Joan Aiken

26. Coffee, Tea, or Me? - "Trudy Baker" aka Donald Bain

27. Fifth Avenue, 5 AM: Audrey Hepburn, Breakfast at Tiffany's, and the Dawn of the Modern Woman- Sam Wasson

28. Audrey: Her Story- Alexander Walker

29. The Complete Films of Audrey Hepburn - Jerry Vermiyle

30. Audrey Hepburn: An Elegant Spirit, a Son Remembers- Sean Hepburn Ferrer

31. Gigi- Collette

32. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes- Anita Loos

33. Chalice- Robin McKinley

34. Dragon's Bane - Patricia Wrede

35. The Golem and the Jinni- Helene Wecker

36. The Prince and the Dressmaker- Jen Wang

37. The Path Made Clear- Oprah Winfrey

38. Lumberjanes- Shannon Watters, Grace Ellis, Gus Allen, and ND Stevenson

39. The Hidden Palace - Helene Wecker

40. Brazen: Rebel Ladies Who Rocked the World- Penelope Bagieu

41. Strange Practice- Vivian Shaw

42. Dreadful Company- Vivian Shaw

43. All Out: The No-Longer-Secret Stories Of Queer Teens Throughout The Ages- edited by Saundra Mitchell

44. The Library at Mount Char- Scott Hawkins

45. Grave Importance- Vivian Shaw

46. Verity- Colleen Hoover

47. Bravely- Maggie Stiefvater

48. 1602- Neil Gaiman

49. She Come By It Natural: Dolly Parton and the Women Who Lived Her Songs- Sarah Smarsh

50. Gallant- V.E. Schwab

51. Lore Olympus Vol. 1- Rachel Smythe

52. I'll Have What She's Having: My Adventures in Celebrity Dieting- Rebecca Harrington

53. Lore Olympus Vol. 2- Rachel Smythe

54. Moon Cakes- Suzanne Walker & Wendy Xu

55. The Tea Dragon Society- Katie O'Neill

56. The Tea Dragon Festival- Katie O'Neill

57. Travels with Foxfire: Stories of People, Passions, and Practices from Southern Appalachia- Foxfire Fund Inc.

58. My Year of Rest and Relaxation - Ottessa Moshfegh

59. Seance Tea Party- Reimenga Yee

60. Dolly Parton, Songteller: My Life in Lyrics- Dolly Parton and Robert K. Oermann

61. Lightfall: The Girl and the Galdurian

62. Tidesong- Wendy Xu

63. Name of the Wind- Patrick Rothfuss

64. The Girl from the Sea- Molly Knox Ostertag

65. Lightfall: The Shadow of the Bird

66. Neon Gods- Katee Robert

67. The Lighthouse Witches- C. J. Cooke

68. Six Crimson Cranes- Elizabeth Lim

69. I'd Rather Be Reading: The Delights and Dilemmas of the Reading Life- Anne Bogel

70. The Secret History- Donna Tartt

71. The Near Witch- V. E. Schwab

72. The Good Demon- Jimmy Cajole

73. The Illustrated Man - Ray Bradbury

74. Nettle & Bone- T. Kingfisher

75. Dracula- Bram Stoker

76. My Best Friend's Exorcism- Grady Hendrix

77. Batman: The Ultimate Evil- Andrew Vachss

78. World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other Astonishments- Aimee Nezhukumatathil

79. Odd and the Frost Giants- Neil Gaiman

80. How to Hygge: The Nordic Secrets to a Happy Life- Signe Johansen

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

hooptober 2022 6/31: night of the demon (1980, dir. james c. wasson)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Night of the Demon (1980)

#Night of the Demon#80s#James C. Wasson#horror#Horror Movies#blood#scream#hanging upside down#drip#grindhouse#vhs#video nasty#bleeding#b movie#cult#cinema#film#movie#gif#my gif#my gifs#cult films

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Night of the Demon (1980)

#night of the demon#james c. wasson#Michael Cutt#joy allen#bob collins#jody lazarus#rick fields#michael lang#melanie graham#shannon cooper#paul kelleher

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Night of the Demon by James C. Wasson (1980)

#Night of the Demon#James C. Wasson#1980s#80s horror#fright night#that place and time#so long ago#when the warmest glow#came from the bright red blood

1 note

·

View note

Text

Night of the Demon (1980)

Dir. Director

☆James C. Wasson Michael Cutt Joy Allen Bob Collins☆

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

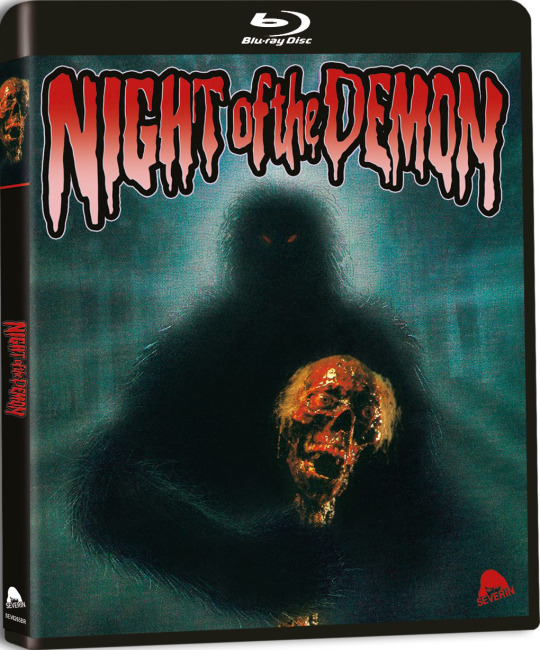

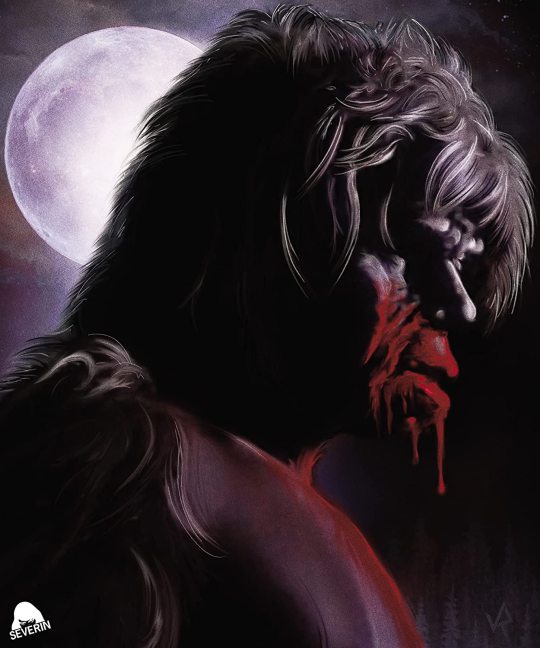

Night of the Demon will be released on Blu-ray on February 22 via Severin Films. The 1980 Bigfoot horror movie includes reversible artwork and a slipcover featuring new art (pictured below).

James C. Wasson directs from a script by Mike Williams. Michael Cutt, Joy Allen, Robert Collings, Jodi Lazarus, Richard Fields, Michael Lang, and Melanie Graham star.

Night of the Demon has been newly scanned in 2K from the recently discovered 35mm answer print with mono audio. An unreleased 1964 film titled Fraternity of Horror is included among the special features, which are detailed below.

Disc 1 special features:

Interview with director James C. Wasson

Interview with producer Jim L. Ball

Interview with cinematographer John Quick

Fraternity of Horror - Previously unreleased 1964 horror film produced by Night of the Demon producer Jim L. Ball

Trailer

Disc 2 special features:

Cryptid Currency: Transgression Aggression In Bigfoot Cinema — Video essay by The Bigfoot Filmography author David Coleman

Interview with Cryptid Cinema co-author Stephen R. Bissette

Interview with When Roger Met Patty author William Munns

Interview with Boggy Creek Casebook author Lyle Blackburn

Ban the Sadist Videos! - 2005 Video Nasty documentary featurette

Ban the Sadist Videos! Part 2 - 2006 Video Nasty documentary featurette

Interview with Ban the Sadist Videos! director David Gregory

Amid the gush of early ‘80s low-budget backwoods horror, only one lost classic brought together softcore sex, hardcore violence, Satanic sex cults and a limb-tearing, gut-slinging, dick-ripping beast for “the best and bloodiest Bigfoot movie ever made.” (Buried.com): When a group of Anthropology students heads deep into the forest to investigate a series of Sasquatch attacks, they’ll discover an immortal brain-blast of crazy hermits, mutilated Girl Scouts, interspecies copulation and “one of the goriest final scenes in the whole history of splatter flicks” (A Slash Above).

Pre-order Night of the Demon.

#night of the demon#horror#80s horror#1980s horror#bigfoot#sasquatch#cryptid#cryptozoology#yeti#skunk ape#severin films#dvd#gift#cult classic#cryptozoolologist

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

sort poems by themes/authors

note: most of these embedded links don’t work & i’m not tech savvy enough to fix it, but you can always use the search function on top of the page. alternatively, you can type /tagged/author’s name or tagged/theme to the end of the home address to find a specific author or theme. replace any space with a hyphen.

example:

wintryblight.tumblr.com/tagged/richard-siken

wintryblight.tumblr.com/tagged/lingering-love

themes

perseverance

nature

food

recovery/healing

the body

grief

death

pain/sickness

childhood

loneliness

nostalgia

freedom

relationships

queerness

lesbians

desire

depression

stagnation

perseverance

hope

love

lingering love

unloved

unrequited love

intense love

fear of love

doomed love

heartache

mothers

fathers

family

dysfunction

the mundane

rage

numbness

stagnation

monotony

paralysis

feeling too much

understanding and being understood

music

self-acceptance

self-compassion

self-reliance

forgiveness

the moon

space

rain

bodies of water

travel

writing

personal favourites

prose poetry

authors

Hanif Abdurraquib

Kim Addonizio

Anna Akhmatova

Rosa Alcalá

Elizabeth Alexander

Hala Alyan

Maya Angelou

Cristin O'Keefe Aptowicz

Derrick Austin

Cameron Awkward-Rich

Ellen Bass

April Bernard

Emily Berry

Wendell Berry

John Berryman

Elizabeth Bishop

Anne Boyer

William Brewer

Richard Brostoff

Jericho Brown

Anne Carson

Grace Cavalieri

K-Ming Chang

Jennifer Chang

Tina Chang

Victoria Chang

Hayan Charara

Chen Chen

Inger Christensen

Steven Chung

Christopher Citro

Lucille Clifton

Barbara Cooker

Wendy Cope

Conchitina Cruz

e. e. cummings

Marissa Davis

Meg Day

Lidija Dimkovska

Chelsea Dingman

Sean Thomas Dougherty

Russell Edson

T. S. Eliot

William Fargarson

Megan Fernandes

Nikky Finney

Luiza Flynn-Goodlett

Richard Foerster

Vievee Francis

Clifton Gachagua

Ross Gay

Andrea Gibson

Aracelis Girmay

Jenn Givhan

Louise Glück

Rodney Gomez

Oscar Gonzalez

torrin a. greathouse

Linda Gregg

Jennifer Grotz

Jeff Hardin

Joy Harjo

Robert Hass

Rage Hezekiah

Neil Hilborn

Bill Holm

Marie Howe

Cynthia Huntington

A. Van Jordan

June Jordan

Donald Justice

Anna Belle Kaufman

Sarah Kay

Donika Kelly

Patricia Kirkpatrick

Joanna Klink

Nate Klug

Yusef Komunyakaa

Juliet Kono

Fortesa Latifi

D. H. Lawrence

Li-Young Lee

Joseph O. Legaspi

Alex Lemon

Jan Heller Levi

Robin Coste Lewis

Sandra Lim

Ada Limón

Sarah Lindsay

Timothy Liu

Audre Lorde

Dorianne Laux

Sally Wen Mao

William Matthews

Nathan McClain

Marty McConnell

Sjohnna McCray

Dunya Mikhail

Jennifer Militello

Tatsuji Miyoshi

Kamilah Aisha Moon

Tomás Q. Morín

Robin Morgan

Gina Myers

Maggie Nelson

Pablo Neruda

Hieu Minh Nguyen

Frank O’Hara

Sharon Olds

Akilah Oliver

Mary Oliver

Meghan O'Rourke

Alicia Ostriker

beyza ozer

Shin Yu Pai

Pat Parker

Don Paterson

Octavio Paz

Catherine Pierce

Jon Pineda

Sylvia Plath

Meghan Privitello

Aleida Rodríguez

Claudia Rankine

Paisley Rekdal

Susan Rich

Max Ritvo

Sara Daniele Rivera

Kait Rokowski

Lee Ann Roripaugh

Muriel Rukeyser

Erika L. Sanchez

Sappho

Nicole Sealey

Anne Sexton

Richard Siken

Jared Singer

Scherezade Siobhan

Emily Skaja

Carmen Giménez Smith

Danez Smith

Maggie Smith

Tracy K. Smith

Anne Stevenson

Mark Strand

Truong Tran

Wang Ping

Sanna Wani

Valerie Wetlaufer

Walt Whitman

Michael Wasson

Keith S. Wilson

C. D. Wright

James Wright

Diego Valeri

Jeanann Verlee

Laura Villareal

Ocean Vuong

Jenny Xie

Wendy Xu

John Yau

Emily Jungmin Yoon

Adam Zagajewski

Felicia Zamora

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

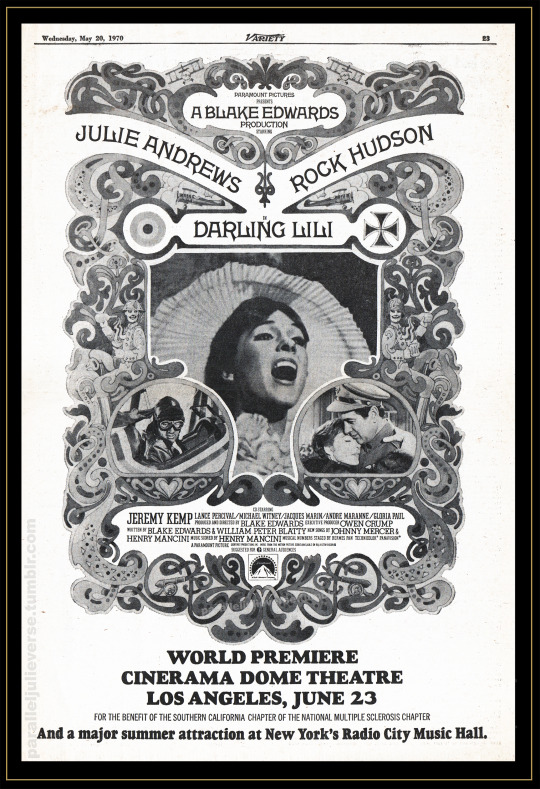

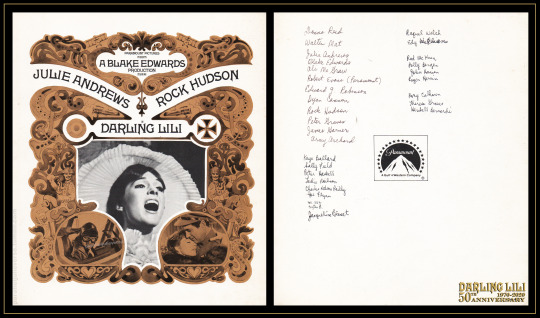

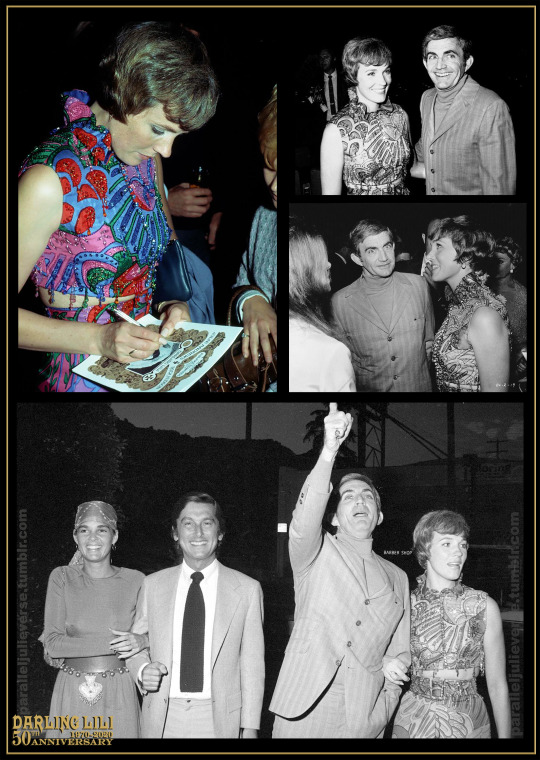

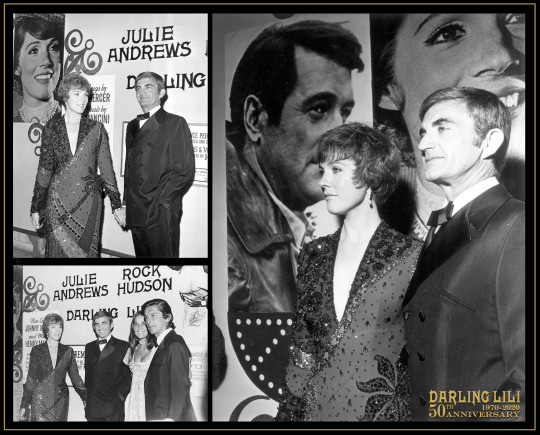

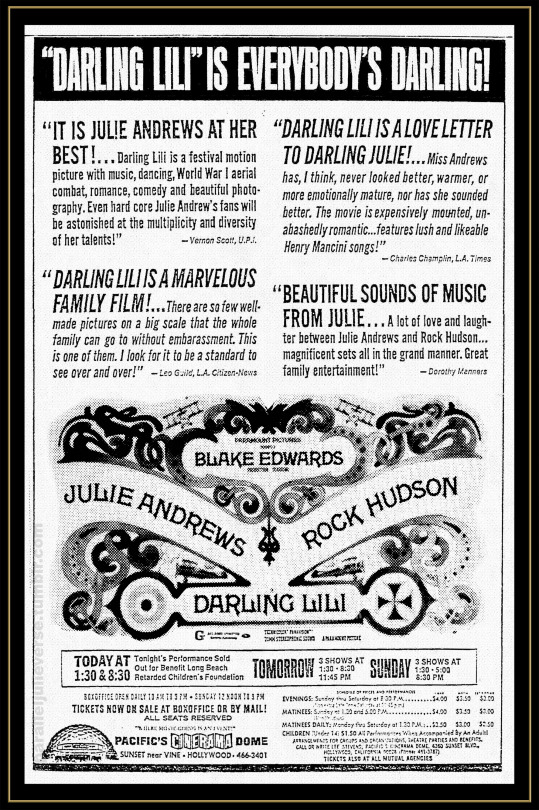

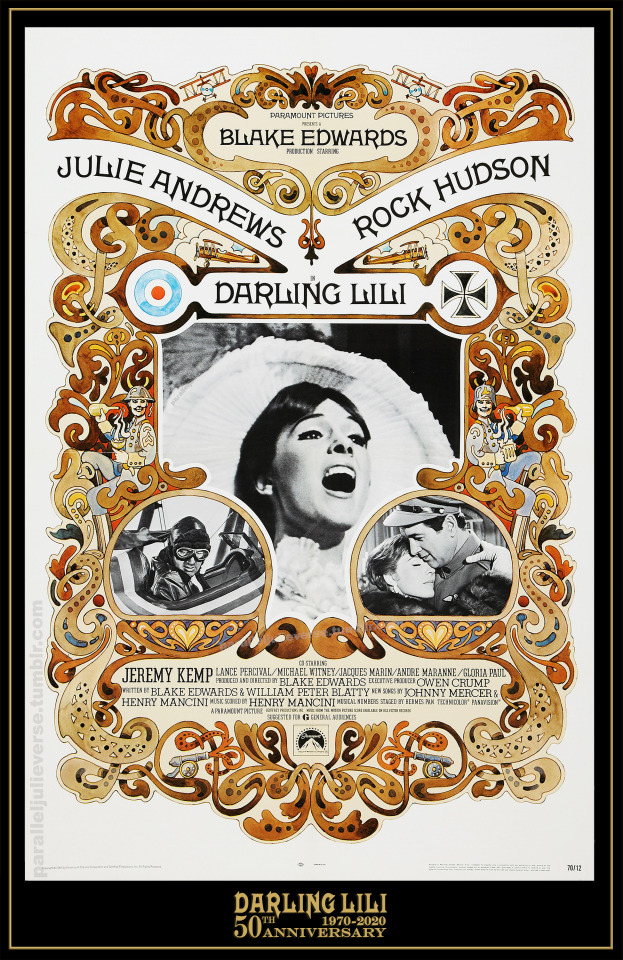

An Angel from Heaven Come to See Us: Darling Lili Turns 50

This week fifty years ago, Darling Lili -- the last of the big Julie Andrews screen musicals of the 1960s -- had its long-delayed World Premiere at Hollywood’s Cinerama Dome on 23 June 1970.

The event marked the symbolic endpoint of a three-plus-year marathon in which the ill-fated production was beset by an endless stream of problems and delays from inclement weather and union pickets on location to studio takeovers and shady refinancing deals (Bart, 63-72; Dick, 146-48; Wasson, 146-48). This litany of setbacks saw the film’s already sizeable budget blowout to era-record levels estimated anywhere, depending on who you spoke to, between $14-25mill. (Warga, C-20; Wedman, 7-A; Kennedy, 175-77). Egos clashed, tempers frayed and recriminations flew with writer-director, Blake Edwards, blaming Paramount Pictures for imposing impossible demands, and studio executives firing back counter-accusations of reckless indulgence and profligacy (Oldham, 24-25; 44-45).

That this highly publicised drama played out against the backdrop of the greatest economic downturn to hit Hollywood in half a century garnered Darling Lili an unenviable advance reputation as “the archetypal flop among big budget Hollywood productions” (Oldham, 44). “Rarely has so much bad word of mouth preceded a picture,” wrote the Saturday Review, “As the shooting schedule increased, as the costs mounted, everyone was certain that Darling Lili would prove to be a landmark disaster” (Knight 22). Another widely syndicated newspaper article dubbed it, “The Most Maligned Movie Ever,” prompting Blake Edwards to fume: “I’ve never known of an important picture in production so talked about, whispered about, and, yes, lied about as Darling Lili” (Manners, B5).

Adding fuel to widespread perceptions of the film as a legendary bomb in the making, the release of Darling Lili was held up for over a year by nervous studio execs. By 1969, Paramount had more big budget roadshow product in the pipelines than any other Hollywood studio (“Par’s Big”, 3). Panicked by the repeated failure of roadshow releases, in general, and the growing cultural backlash against big budgeted musicals, in particular, the studio feared they were “on the verge of an unprecedented financial disaster” and vacillated over how to proceed (Farber, 3). They ordered competing rounds of edits to the film, taking material out to secure a G-rating, then reinserting other material in an effort to broaden appeal (Manners, B5; “Par’s Lili Rated G”,5). There were even rumours the film might not get a release at all. It is “hiding somewhere” and seems to have “just evaporated” noted one newspaper report in late-1969 (Gussow, 62; Benchley, 9).

In December, Paramount finally held two sneak test screenings of Darling Lili in Oklahoma City and Kansas City which proved sufficiently positive for the studio to green-light release (“Kansas”, C2). After the test screenings, Robert Evans, production chief at Paramount and longtime vocal critic of Blake Edwards’s direction of the film, sounded an uncharacteristically upbeat note. “At the end of the film, there was a standing ovation,” he enthused, “and almost all the patrons stopped in the lobby to fill in comments cards...term[ing] Darling Lili as excellent, with special acclaim for both Julie Andrews and Rock Hudson” (Muir, 2-S).

In January 1970, it was announced that Darling Lili would premiere that summer as a hardticket attraction at New York’s Radio City Music Hall (”Par Gets”, 3). The following month, a series of exhibitor previews was held in five major US cities but, in a telling sign the studio still harboured reservations about the film, the trade press was pointedly excluded from all advance screenings ("Not Ready”, 6). This same lingering disquiet resulted in a radically scaled back approach to the film’s release and marketing.

Originally planned as a reserved-seat roadshow attraction, Darling Lili was ultimately repositioned by Paramount as part of what they called their “Big Summer Playoff,” a package of eight films given saturation releases during the summer off-season starting in June (“Paramount’s Summer Playoff”, 5). Only New York and Los Angeles would screen the film as a 70mm reserved-seat attraction; elsewhere, the plan was for the “pic to quickly saturate every major and minor market with single-house firstruns and key city multiples” (ibid.). In an era when studios typically gave their top films staggered releases and only ever issued B-product or second-runs widely during the quiet summer months, this new-style release strategy had a decided air of dump-it-and-run desperation.

The apparent lack of care and finesse in the release of Lili did not go unnoticed. “Darling Lili undoubtedly rank[s] among the unusual summer attractions,” commented one newspaper article, “since one would expect to see th[is] multi-million dollar production around holiday time” (Sar, 4-B). Another bluntly opined that Paramount “seems to have dumped the expensive movie rather than spend any more on it” (Taylor, 21-E). Even Julie, normally the soul of diplomatic discretion in such matters, expressed public dismay at the studio’s handling of the film’s release:

“Three weeks before the opening, there was no advertising campaign. None whatsoever. Paramount didn’t seem to know how it was going to sell the picture--or if. I simply can’t understand an attitude like that” (Thomas, 13).

The sudden shift to a summer saturation release also meant the film’s premiere had to be rescheduled as New York’s Radio City Music Hall wasn’t available till July. In late-May, a matter of mere weeks before the film was set to bow, Paramount announced Darling Lili would now make its world premiere at the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood on June 23 before rolling out nationwide the following day (“‘Darling Lili’ to Premiere,” W-2). The New York premiere, meanwhile, would remain at the Music Hall but delayed a full month after the rest of the country.

Putting on a brave face, Julie and Blake did their best to launch their film. On June 18, they attended a special press preview and celebrity reception hosted by Robert Evans and his then partner, Ali McGraw, at the Director’s Guild Theatre (Sar, 24-A). Dressed in a modish psychedelic Pucci pantsuit -- which fans of Julie-trivia will note was a recycled outfit from her recent NBC TV special with Harry Belafonte -- Julie looked relaxed and radiant or, as one columnist put it, “peachy dandy in her wild patterned party pants” (Browning, 2-13). At the after-show reception, she and Blake mingled warmly with a host of Tinseltown notables including Edward G. Robinson, James Garner, Walter Matthau, George Peppard, Raquel Welch, Sally Field, Dyan Cannon, and Peter Graves (ibid).

The following week, Julie and Blake were back for the premiere proper at the Cinerama Dome on 23 June. Dressed to kill in a sleek beaded cocktail gown, Julie posed for press shots on the red carpet with Blake, Robert Evans and Ali McGraw, and co-star Rock Hudson who attended with longtime friend and agent, Flo Allen. Sponsored by the Southern Californian chapter of VIMS, Volunteers in Multiple Sclerosis, the premiere attracted a capacity crowd with an invitation-only champagne supper held at the theatre after the screening (“Premiere”, IV-8) .

For all the old-school Hollywood trappings of the premiere, the American roll-out of Darling Lili was afforded little sense of showmanship or distinction. The Cinerama Dome would be the film’s only fully reserved-seat roadshow presentation (“’Darling Lili’s’ One Reserve,” 7). The film’s run at New York’s Radio City Music Hall -- which will likely be the subject of another post next month, time permitting -- was another exception but it had a hybrid mix of partial reserved and general admission. Elsewhere, the film was released in what could only be described as a woefully slipshod manner.

The day after the World Premiere, Lili was issued simultaneously to an idiosyncratic assortment of theatres and even drive-ins across the United States including such out-of-the-way places as Lubbock, Texas; Hattiesburg, Mississippi; and Mason City, Iowa. Conversely, several major metropolitan markets didn’t get the film till much later, and some didn’t show it at all. When the film ran it was often booked for a flying season of a week or two -- in some instances, just a few days -- and given little promotion or build-up.

On a PR trip to San Francisco, Blake Edwards was reportedly incensed to discover that Lili was being shown at a local theatre on a double-bill with The Lawyer, an R-rated crime drama (Caen, 6-B). But this was far from an isolated instance. A survey of newspaper advertising from the era shows that, throughout this initial release period, Darling Lili was widely double-billed in US theatres with a range of questionable screen-mates including Downhill Racer, True Grit, Norwood, The Sterile Cuckoo, and Lady in Cement to name a few.

Much like the film’s chequered release pattern, reviews of Darling Lili were sharply mixed. Contrary to the apocalyptic predictions, though, there were surprisingly few outright pans and quite a number of good, even glowing, notices--certainly enough to furnish choice grabs for newspaper ads. Moreover, a common refrain among even lukewarm crits was that the film was far from the disaster everyone anticipated:

“Darling Lili [is] the musical comedy a lot of people have been expecting to be a bomb, but which turns out to be a quite likeable movie” (Crittenden, D-10).

“When a movie becomes notorious like this, everyone expects it to be an unredeeming dud...I’m relieved to say Darling Lili is certainly nobody’s bomb” (Stewart, 28)

“[E]veryone was certain that Darling Lili would prove to be a landmark disaster. Happily, the opposite seems to be the case...it is definitely, joyously, what the industry likes to call an ‘audience picture’ (Knight, 22).

While many reviewers found aspects of the film wanting, they were mostly full of praise for Julie:

“Miss Andrews has, I think, never looked better, warmer or more emotionally mature, nor has she sounded better. The irony is that she projects a richness which is wasted here. It’s like getting Horowitz to play Chopsticks” (Champlin, IV-1).

“Andrews...is one of the last of the great English music-hallmarks. She can sing effortlessly, make a mug or a moue with equal facility, throw away a line and reel it back in with the best—when she is given half a chance. Her latest, Darling Lili, is only a quarter of a chance (Kanfer, 78).

“In Darling Lili...Julie Andrews is the most pleasant actress any audience ever had and that’s what counts...The picture’s weaknesses are Hudson and the war...But I think Julie Andrews is enough” (Geurink, 6-T).

“The best way to enjoy Darling Lili is to look upon it as escape fare [with] Miss Andrews’ golden voice for listening pleasure...While she deserves something much better than her role in Darling Lili, Julie Andrews...is still an out and out professional” (Blakley, 6-1).

“Miss Andrews...is absolutely perfectly suited to the title role. Her voice, her mannerisms, her beauty and her obvious delight with the entire project pay off in one of the finest performances of her career” (Fanning, 17).

“The film’s bright moments belong to Miss Andrews. She is a complete entertainer, and tho [sic] she is center stage for nearly the entire film, one never tires of her pure voice and intelligent acting” (Siskel, 12).

Alas, the better-than-expected reviews were not enough to save Darling Lili commercially. By the end of its domestic run, the film had earned a meagre $3.2mill in rentals, placing it 37th in Variety’s list of annual box-office rankings for 1970 (“US Films,” 184). Instructively, the film posted its best returns at the two theatres where it was exhibited with some modicum of prestige showmanship: the Cinerama Dome and Radio City Music Hall. In the case of the latter, Lili actually broke house records for a non-holiday release (“Radio City,” 12). Combined, these two venues accounted for over a third of the film’s entire North American boxoffice grosses. It’s a curious footnote to the whole sorry saga of Darling Lili which does suggest that, while the film would likely never have been a hit, it could certainly have done much better had its distribution and exhibition been more carefully managed. But that is a discussion for another time and another post...

Sources:

Bart, Peter. Infamous Players: A Tale of Movies, the Mob (and Sex). New York: Hachette, 2011.

Benchley, Peter. “1969 A Watershed Year for Motion Picture Industry.” Journal Gazette. 6 January 1970: 9.

Blakley, Thomas. “Julie Andrews Eyes a New Start.” Pittsburgh Press. 28 June 1970: 6-1.

Browning, Norma Lee. “Hollywood Today: Julie’s Reception.” Chicago Tribune. 22 June 1970: B-13.

Caen, Herb. “It’s News to Me.” Hartford Sentinel. 5 August 1970: 6-B.

Canby, Vincent. “Is Hollywood in Hot Water?” New York Times. 9 November 1969: D1, D37.

Champlin, Charles. “Movie Review: ‘Darling Lili’ Has World War I Setting.” Los Angeles Times. 24 June 1970: IV-1, 13.

Crittenden, John. “’Darling Lili’ Surprises by Being Very Pleasant.” The Record. 24 July 1970: D-10.

“’Darling Lili’ to Premiere in Hollywood June 24.” Boxoffice. 25 May 1970: W2.

“’Darling Lili’s’ One Reserve Seat Date.” Variety. 3 June 1970: 7.

Dick, Bernard F. Engulfed: The Death of Paramount Pictures and the Birth of Corporate Hollywood. Louisville, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2015.

Fanning, Win. “The New Film: Andrews, Hudson in ‘Darling Lili’ at Squirrel Hill.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 25 June 1970: 17.

Farber, Stephen. “End of the Road?” Film Quarterly. 23: 2. Winter 1969-70: 3-16.

Geurink, Bob. “Julie’s Pretty Darling in ‘Lili’.” Atlanta Constitution. 11 July 1970: 6-T.

Gussow, Mel. “Excitement Fills Premier of ‘Dolly’: But Air of Festivity Belies Future of Movie Musicals.” New York Times. 18 December 1969: 62.

Higham, Charles. “Turmoil in Film City.” Sydney Morning Herald - Weekend Magazine. 25 May 1969: 19.

Holston, Kim R. Movie Roadshows: A History and Filmography of Reserved-Seat Limited Showings, 1911-1973. Jefferson, NC: McFarlane and Co, 2013.

Kanfer, Stefan. “Cinema: Quarter Chance.” Time. 96: 4. 27 July 1970: 78.

“Kansas City.” Boxoffice. 22 December 1969: C2.

Knight, Arthur. “How Darling was My Lili.” Saturday Review. 18 July, 1970: 22.

Krämer, Peter. The New Hollywood: From Bonnie and Clyde to Star Wars. London: Wallflower, 2005.

Manners, Dorothy. “The Most Maligned Movie Ever.” San Francisco Examiner. 15 March 1970: B5.

Mills, James. “Why Should He Have it?” Life. 7 Match 1969: 63-76.

Muir, Florabel. “Hollywood: It Snowed Customers.” Daily News. 21 December 1969: 2S.

“Not Ready for Trades But Exhibs See ‘Lili’.” Variety. 28 January 1970: 6.

Oldham, Gabriella, ed. Blake Edwards: Interviews. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2018.

“Par Gets Hall’s Summer Spot for its ‘Darling Lili’.” Variety. 21 January 1970: 3.

“Para. Sets Preview Series in Five Cities for ‘Lili’.” Boxoffice. 26 January 1970: 10.

“Paramount’s Summer Playoff Strategy: 5,000 Bookings for Eight Major Films.” Variety. 3 June 1970: 5.

“Par’s Big Roadshow Splash.” Variety. 25 June 1969: 3.

“Par’s Lili Rated G.” Variety. 24 September 1969: 5.

“Premiere.” Los Angeles Times. 25 June 1970: IV-8.

“Radio City Music Hall’s All-Time Boxoffice Darling.” Variety. 5 August 1970: 12.

Sar, Ali. “Paramount Unveils Two Top Pictures.” Van Nuys News. 21 June 1970: 24-A.

Sar, Ali. “Curiosity Films: Plagued Studios Hope.” Van Nuys News. 28 June 1970: 4-B.

Siskel, Gene. “The Movies: ‘Darling Lili’.” Chicago Tribune. 22 August 1970: 12.

Sloane, Leonard. “At Paramount, Real Financial Drama.” New York Times. 28 November 1969: 48.

Stewart, Perry. “Warm Kiss from ‘Lili’.” Fort-Worth Star-Telegram. 1 Juy 1970: 28.

Stuart, Byron. "Pictures: Big Budget’s Big Bust-Up." Variety. 23 July 1969: 3, 20.

Taylor, Robert. “‘Lili’ Can Be Charming.” Oakland Tribune. 27 June 1970: 21-E.

Thomas, Bob. “Julie Andrews Praises ‘Lili’.” Courier-News. 15 September 1970: 13.

“U.S. Films’ Share-of-Market Profile.” Variety. 12 May 1971: 36-38, 122, 171-174, 178-179, 182-183, 186-187, 190-191, 205-206.

Warga, Wayne. “Stanley Jaffe: Paramount Risk Jockey.” Los Angeles Times. 24 January 1971: C1, C20-21.

Wasson, Sam. A Splurch in the Kisser: The Movies of Blake Edwards. Middletown: Weslayan University Press, 2009.

Wedman, Les. “The End of the Roadshow.” Vancouver Sun. 9 January 1970: 7A.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2020

#julie andrews#Darling Lili#fiftieth anniversary#1970#cinerama dome#film premiere#paramount#film history#hollywood#classic film#blake edwards

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Night of the Demon - USA, 1980

Night of the Demon is a 1980 American horror feature film directed by James C. Wasson from a screenplay written by Mike Williams.

Presented in flashback and with a brief found footage scene, the film tells the story of an anthropology class on an expedition into the American wilderness to find the truth behind the Sasquatch legend.

Along the way, the team learns about the creature’s previous…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baby’s First Literature Review

Racism: Internal and External

Department of Psychology, Howard University

PSYC 016-01: Psychology New Student Orientation

November 11, 2020

Racism: Internal and External

The Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 has sparked a major mainstream conversation about racism in the United States. Different expressions of racism, especially antiblackness, can be observed throughout the world, but most of the literature on racism comes from the U.S. Conversations on antiblack racism in America date back to 1773, when the first African American author was published (Library of Congress). Phyllis Wheatley, the aforementioned author, was not critical of her white oppressors but she did discuss the struggle of being enslaved, though she mainly focused her works around her Christianity (Library of Congress). In the over 200 years since then, a nearly infinite amount of content has been produced on the topic of racism.

Racism is actually a fairly new concept in human history. “Race” as a word first entered the English language in the late 1500s (Wade). Its earlier meaning was synonymous with “kind” or “type”, and was a more general term (Wade). It was not until the 1700s that it began to be used commonly to refer to humans in a sorting manner. Built into this use of the word was a type of ranking system and in America, European settlers were at the top, followed by the conquered Native Americans, with African slaves holding the lowest rank (Wade). It is important to note that race is not a categorization system based on science. While there are physical differences between races of people, and some genetic qualities may be more common among individuals of a certain race, race is a social construct. This is most obvious when examining concepts like “whiteness”, and how the ingroups and outgroups of whiteness have changed over time. People of Irish descent were at one point not considered white, but now they generally are (Wade). This is not to imply that there are not real life repercussions associated with the concept of race, but rather to add context to the conversation and to further expose how absurd white-supremacy, and racism as a whole, are.

Black people are central to the discussion of racism in America because of the long history of antiblackness. Racism is something black folks are faced with from “crib to coffin” (Jones, 2020). Racism is often treated as a purely external issue, but its influence is so prevalent that it has bred “internal racism” (Sosoo, 2019). Both contribute to the pain, suffering, and oppression of black people. Racism wreaks havoc on black people’s self-image and mental health. Which is worsened by the fact that racism and racial disparities are even commonplace in the medical field. This creates a positive feedback loop where a black individual may seek medical assistance in coping with stress linked to racism they face, and they are then confronted with racism coming from their healthcare providers.

Shawn Jones (2020) discussed African Americans attempting to cope with racism-related stress throughout their lifetime . It seems as though addressing and even dismantling internalised racism may be tangential to this process. Effua Sosoo studied “The Influence of Internalized Racism on the Relationship Between Discrimination and Anxiety” among college students (2019). Internalized racism further perpetuates racism and it’s deconstruction from within oneself is crucial to helping black Americans cope with and heal from the racism they face.

Jones (2020) breaks down racism throughout a black individual’s life, chronologically, as follows:

To illustrate, research suggests that racism—and not simply racial group—drives the persistent low birth weight disparities among Black babies (De Maio, Shah, Schipper, Gurdiel, & Ansell, 2017). As these children develop, research indicates that they will likely face differential treatment as early as preschool, an age wherein Black children’s suspension rates (48%) are nearly twice those of their White counterparts (26%; U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, 2014). The period of adolescence then brings stories such as one in which a 16-year-old Black teen was taunted publicly for eating chicken at a pep rally contest, with video and inflammatory narrative shared across social media by his White peers (Wootson, 2017). As racism persists in early and middle adulthood, Black Americans may contemplate abbreviating their names given persistent biases in hiring practices (Nunley, Pugh, Romero, & Seals, 2015). Racist reverberations extend into older adulthood for Black Americans, with burgeoning research suggesting that poverty and racism raise the risk of developing Alzheimer’s (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017). These correlations and numerous others have been further synthesized by an at-once impressive and disheartening number of reviews linking racism and health or well-being across hundreds of studies spanning the last three decades (see Hope, Hoggard, & Thomas, 2015; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Pieterse, Todd, Neville, & Carter, 2012; Priest et al., 2013; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). These reviews generally congregate around one reality: that racism is a pernicious and unique stressor, with the potential to thwart the physical, physiological, and psychological health of Black Americans. This developmental overview seeks to add to this growing body of literature, applying a life-course perspective to investigate racism-related stress (RRS) and coping over time. (para. 2)

The study goes on to lay out their parameters, explaining (Jones, 2020),

As articulated by S. P. Harrell (2000) and derived from Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) broader conceptualization of stress, RRS refers to “race-related transactions between individuals or groups and their environment that emerge from the dynamics of racism, and that are perceived to tax or exceed existing individual and collective resources or threaten well-being” (S. P. Harrell, 2000, p. 44). Harrell describes six prominent types of RRS: (a) racism-related life events (time-limited, specific life experiences), (b) vicarious racism experiences (observation and report of others’ racism experiences), (c) daily racism microstressors (subtle slights and exclusions), (d) chronic-contextual stress (social systemic and institutional racism), (e) collective experiences (“cultural-symbolic and sociopolitical manifestations of racism,” p. 46), and (f) transgenerational transmission (discussions of historical events). Importantly, these various types of racism-related stressors may (and often do) co-occur and interact, as well as interact with other stressors, including general and other-social-roles-related stressors (e.g., sexism, heterosexism, Islamophobia). (para. 5)

Interestingly, internalized racism is not included in any of six types of racism defined by S.P. Harrell. This is important as Sosoo (2019) explains “numerous studies have linked internalized racism to metabolic health (e.g., Chambers et al., 2004), but it has also been associated with psychological distress (Molina & James, 2016; Szymanski & Obiri, 2011)” (para. 2). The study was conducted among college students which fits well into Jones discussion. It concludes with stating that,

Analyses revealed that the relation between racial discrimination and psychological distress may depend on other factors such as levels of internalized racism. A significant interaction was found between racial discrimination and internalization of negative stereotypes such that racial discrimination was associated with increased anxiety symptom distress at T2 for individuals with moderate and high, but not low, levels of internalization of negative stereotypes. (Sosoo, 2020, para. 29)

To give credit where credit is due, both studies show deep analysis. However, Jones’ (2020) study went further in examining coping methods utilized by African Americans, beyond looking at racism from various input sources. Both send a strong message about the importance of addressing racism in America, and both point out the negative physical and mental effects racism has on black people. They both argue for a reduction of prevalence of racial stereotypes and racial discrimination. Sosoo’s study reveals that individuals who experience internalized racism “are more likely to report experiences of anxiety symptom distress, such as distress from feeling tense or scared” (2019, para. 29). This is potentially explained by the idea that their “experiences of racial discrimination may serve as a confirmation of these negative views, leading to psychological and physiological symptoms of anxiety” (Sosoo, 2019, para. 29). Therefore it is vital that all forms of racism must be considered, addressed, and dismantled for the sake of black people’s overall health, happiness, and wellbeing.

References

Jones, S. C., Anderson, R. E., Gaskin-Wasson, A. L., Sawyer, B. A., Applewhite, K., & Metzger, I. W. (2020). From “crib to coffin”: Navigating coping from racism-related stress throughout the lifespan of Black Americans. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(2), 267-282. doi:10.1037/ort0000430

Library of Congress. (n.d.). Revolutionary Period (1764-1789). Retrieved November 11, 2020, from http://www.americaslibrary.gov/jb/revolut/jb_revolut_poetslav_1.html#:~:text=Wheatley grew up to be,learn to read and write?

Sosoo, E. E., Bernard, D. L., & Neblett, E. W. (2020). The influence of internalized racism on the relationship between discrimination and anxiety. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 26(4), 570-580. doi:10.1037/cdp0000320

Wade, P. (2020, July 28). The History Of The Idea Of Race. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/race-human/The-history-of-the-idea-of-race

0 notes