#kochai

Text

Everywhere I went, I felt as if I had to beg some little god to have mercy on my family. I began to hate this country and its myriad of systems and courtrooms and departments, which existed, it seemed, solely to exploit or ignore the most overworked and underprivileged members of our society.

“Labor is invisible,” a professor once told me, years later. He pointed out the window of our classroom, toward the green quad. “You see those clipped trees. That perfectly cut lawn. You walk past them every day. But who shapes the trees? Who cuts the lawn? And why do you never see them? Everywhere you go, you are surrounded by the products of labor. Every clean sidewalk, every polished hallway, every blade of cut grass. Our world cannot function without them, and yet the laborer remains unseen and unheard. Why is that? What is it about our national culture, or our economic structures, that necessitates this invisibility? Why is it that America turns its laborers into spectres?”

I thought of my father waking before dawn, driving hours through the cool morning mist, to cut grass, to spray and inhale chemicals—to become a spectre. He had done everything right. He worked like an animal for his employers. He had no criminal record. His credit was great. He didn’t drink or do drugs. He went quietly to work every morning and came quietly home every evening. He obeyed his bosses and won employee of the year multiple times. He paid his taxes and mowed his lawn and met with his children’s teachers. He was the ideal immigrant. The American Dream personified. And yet, the moment his broken body could no longer be exploited for its labor, he was doubted and ignored and humiliated. Everywhere he turned for help—workers’ compensation or welfare or Social Security or Medi-Cal or the court system itself—he was treated like a scam artist. A crook. The bureaucracy inherent to these programs turned him into a stack of documents. A list of ailments. He was dismissed and forgotten. Just another spectre in America.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

He watched clip after clip of systematic rape and mutilation and murder, and all the while, he kept justifying that to take witness, to record and analyze atrocities, was his duty as a scholar, as a historian, as a . . . But the clips, the photographs, even the textual descriptions, warped something in his understanding of his own body. Often, he stared at his hands, touched his skin, and attempted to make sense of all the atrocities that could be committed against flesh, and this contemplation left him sleepless and depressed and afraid. He wondered why God had made humans so malleable, so soft, only to be torn apart on highways or systematically mutilated in dark chambers and black sites, at the hands of beloved men, until the mind could no longer comprehend the suffering of the body and destroyed itself.

Jamil Jan Kochai, “The Tale of Dully’s Reversion,” in The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

And why must we always ruin what is beautiful with what is true?

Jamil Jan Kochai, “Saba’s Story” from The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories

#Jamil Jan Kochai#The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories#quote#fiction#short stories#2023 reads

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Picks: The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories

I'm still reading through the best books of 2021/2022, and my fav so far is The Haunting of Hajji Hotak. Masterful and riveting, these stories of war and diaspora will break your heart and bind it up again. Jamil Jan Kochai is an author to watch. #reading

I’m continuing to work my way through titles that made waves in 2021 and 2022, and this is my favorite so far. If you are in the market for masterful short stories, Jamil Jan Kochai’s collection will not disappoint. A National Book Award finalist, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak feels like it enfolds the entire world in its embrace, spanning the United States and Afghanistan, teen gamers and aging…

View On WordPress

#Afghan American authors#Afghan American fiction#Afghanistan#Afghanistan books#best books 2022#Enough!#Jamil Jan Kochai#literary fiction#Metal Gear Solid#National Book Award finalist#Return to Sender#short story collections#The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Lily has recently, and secretly, become a vegetarian. Two weeks earlier, she came home weeping to her mother after having witnessed the vehicular maiming of a duck that was crossing the street with a line of her ducklings. Lily had cradled the duck in her death throes, surrounded by her little ducklings—which, Lily swore, were crying out for their mother. Together, Habibi and Lily wept for the little orphaned ducklings. Later that day, Lily informed her mother that she could not bring herself to eat the chicken korma she had prepared, and Habibi decided not to scold her (a decision she would come to regret). At first, it was only chicken, but then Lily confessed to her mother that she could no longer stomach beef or lamb, the rest of the culinary trinity of Hajji’s household. Habibi made an effort to explain to her daughter that vegetarianism was a slippery slope toward feminism, Marxism, Communism, atheism, hedonism, and, eventually, cannibalism. “Animals are animals,” her mother explained, deftly, “and humans are humans, and when you begin mixing up the two you will find yourself kissing chickens and eating children.””

-The Haunting of Hajji Hotak

By Jamil Jan Kochai

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

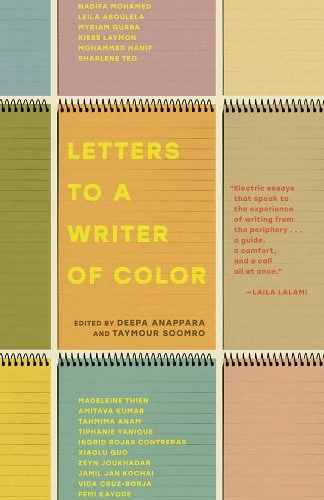

Letters to a Writer of Color

Taymour Soomro (Editor) Deepa Anappara (Editor)

A vital collection of essays on the power of literature and the craft of writing from an international array of writers of color, sharing the experiences, cultural traditions, and convictions that have shaped them and their work "Electric essays that speak to the experience of writing from the periphery . . . a guide, a comfort, and a call all at once."--Laila Lalami, author of Conditional Citizens Filled with empathy and wisdom, instruction and inspiration, this book encourages us to reevaluate the codes and conventions that have shaped our assumptions about how fiction should be written, and also challenges us to apply its lessons to both what we read and how we read. Featuring: - Taymour Soomro on resisting rigid stories about who you are

- Madeleine Thien on how writing builds the room in which it can exist

- Amitava Kumar on why authenticity isn't a license we carry in our wallets

- Tahmima Anam on giving herself permission to be funny

- Ingrid Rojas Contreras on the bodily challenge of writing about trauma

- Zeyn Joukhadar on queering English and the power of refusing to translate ourselves

- Myriam Gurba on the empowering circle of Latina writers she works within

- Kiese Laymon on hearing that no one wants to read the story that you want to write

- Mohammed Hanif on the censorship he experienced at the hands of political authorities

- Deepa Anappara on writing even through conditions that impede the creation of art

- Plus essays from Tiphanie Yanique, Xiaolu Guo, Jamil Jan Kochai, Vida Cruz-Borja, Femi Kayode, Nadifa Mohamed in conversation with Leila Aboulela, and Sharlene Teo The start of a more inclusive conversation about storytelling, Letters to a Writer of Color will be a touchstone for aspiring and working writers and for curious readers everywhere.

(Affiliate link above)

272 notes

·

View notes

Text

You can vote even if you're not sure you'll be able to come!

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Midway through Jamil Jan Kochai’s collection The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories, which maps generations of Afghan and Afghan American lives against over a century of entwined wars, sits what appears to be a résumé. Entitled “Occupational Hazards,” it meticulously records the everyday labors of an Afghan man: [...] his “[d]uties included: leading sheep to the pastures”; from 1977–79, “gathering old English rifles” left over from the last war while being recruited into a new war; in 1980–81, “burying the tattered remnants of neighbors and friends and women and children and babies and cousins and nieces and nephews and a beloved half-sister”; [...] becoming a refugee day-laborer in Peshawar, Pakistan; in 1984, becoming a refugee in Alabama, where he worked on an assembly line with other Asian migrants whom the white factory owner used to push out the local Black workforce; and so on. Dozens of events, from the traumatic to the mundane, are cataloged one by one in prose that is at once emotionless and overwhelming. [...] Kochai interviewed his father for the résumé’s occupational trajectory [...]. An Afghan shepherd [...] is displaced by imperial wars and then, in the heart of empire, is conscripted into racialized domestic economies [...]. [M]ethodically translating lived violence via a résumé, a bureaucratic form that quantifies labor in its most banal functionality, paradoxically realizes the spectacular breadth of war and how it organizes life’s possibilities. [...]

---

In this collection, war is past, present, and plural. In Afghanistan, Kochai recounts the lives of Logaris and Kabulis, against the backdrop of the US occupation, still dealing with the detritus of previous wars - British, Soviet, and civil - including their shrines, mines, and memories. In the United States, Afghan Californians experience the diasporic conditions of war -- state neglect of refugees combined with targeted surveillance -- amid the coming-of-age of a second generation that must confront inherited traumas while struggling to build political solidarities with other displaced youth.

These 12 stories explore the reverberations between historical and psychic realities, invoking a ghostly practice of reading. Characters, living and dead, recur across the stories [...]. Wars echo one another [...]. Scenes and states mirror each other, with one story depicting Afghan bureaucracies that disavow military and police violence while another depicts US bureaucracies that deny social services to unemployed refugees. History itself is layered and unresolved [...]. Kochai, who was born in a refugee camp in Peshawar, writes from the position of the Afghan diaspora [...]. In August 2021, the US relegated Afghanistan to the past, declaring the “longest American war” over. Over for whom? one should ask. [...] War, in other words, is not an event but a structure. [...]

---

In Kochai’s collection, war is not the story; rather, war arranges the scenes and life possibilities [...]. Kochai carefully puts war itself, and the warmakers, in the narrative background [...].

This is a historically incisive narrative design for representing Afghanistan. Kochai challenges centuries of Western colonial discourses, from Rudyard Kipling to Rambo, that conflate Afghanistan with violence while erasing the international production of that violence as well as the social and conceptual worlds of Afghans themselves. Instead, this collection moves the reader across Afghans’ transcontinental, intergenerational, and multispirited social worlds -- including through stories of migrations and returns, homes populated by the living and the martyred, language that enmeshes Dari, Pashto, and Northern California slang, as well as the occasional fantastical creature [...].

---

Like Kochai’s debut novel 99 Nights in Logar (2019), this collection merges realism and the fantastic, oral and academic histories, Afghan folklore and Islamic texts, giving his fiction a dynamic relation to history. Each story is an experiment, and many of them are replete with surreal or magical elements [...].

As in Ahmed Saadawi’s 2013 novel Frankenstein in Baghdad, a nightmarish sensorium collides with a postcolonial body politics [...].

In a recent interview, Kochai said that writing about his family’s experiences of war has compelled him to explore “realms of the surreal or magical realism […] because the incidents themselves seem so unreal […]. [I]t takes years and decades to even come to terms with what had actually happened to them before their eyes.” He points not to a documentary dilemma but to an epistemological one. While some scholars have argued that fantastic genres like magical realism are often conflated with exoticized imaginaries of the Global South, others have defended the form’s critical possibilities for rendering complex realities and multiple modes of interpretation. Literary metaphors, whether magical or otherwise, are always imprecise; as Afghan poet Aria Aber puts it, “you flee into metaphor but you return / with another moth / flapping inside your throat.” [...]

Kochai does not “escape” into the surreal or magical as fictions but as other ways of reckoning with war’s pasts ongoing in the present.

---

All text above by: Najwa Mayer. “War Is a Structure: On Jamil Jan Kochai’s “The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories.”“ LA Review of Books (Online). 20 December 2022. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism.]

#haunting#tidalectics#carceral geography#intimacies of four continents#multispecies#gothic#geographic imaginaries#frankenstein in baghdad#afghan#carceral archipelago

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 books to read in 2024

inspired by @earlymoderngothic - this year i tried to have at least half the list be books i own (these are marked with *)

Cheon Myeong-kwan, Whale*

Émile Zola, Nana*

Ann Radcliffe, The Mysteries of Udolpho*

Zaffar Kunial, England's Green

Vladimir Nabokov, Other Shores [Владимир Набоков, Другие берега]*

Patrick Chamoiseau, Texaco*

Marcel Proust, Du côté de chez Swann*

Bae Suah, Recitation*

Oksana Lutsyshyna, Ivan and Pheba [Оксана Луцишина, Іван і Феба]

Natalia Ginzburg, All Our Yesterdays*

Maïssa Bey, Bleu, blanc, vert*

Doireann ní Ghríofa, A Ghost in the Throat*

Jamil Jan Kochai, 99 Nights in Logar*

Robert Graves, Goodbye to All That*

Aleksandr Chudakov, Darkness Falls on the Old Steps [Александр Чудаков, Ложится мгла на старые ступени]

Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography

Emma Southon, A Fatal Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum

Yu Miri, End of August*

Latifa al-Zayyat, The Open Door

Alice Notley, The Descent of Alette

Valeryan Pidmohylnyi, City [Валер'ян Підмогильний, Місто]

Ellen Wood, East Lynne

Emi Yagi, Diary of a Void

Svetlana Aleksievich, Second-Hand Time [Светлана Алексиевич, Время секонд-хэнд]

here's last year's list -- i actually did pretty well, what with books i'm still reading and all. and you'll see a couple have migrated onto this one

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Best books I’ve read this year: end of year edition

I read a lot of great books this year so it’s really hard to narrow down my favorites, but here are some I read during the past six months that I most enjoyed. (You can read part one here).

Best new releases: fiction

Not a ton of novels I loved but I thought Afghan American author Jamil Jan Kochai’s short story collection The Haunting of Hajji Hotak was absolutely stellar.

Honorable mentions: Flight by Lynn Steger Strong and Small Game by Blair Braverman.

Best new releases: nonfiction

Partisans by Nicole Hemmer - argues convincingly that Trump was the natural evolution of decades of reactionary GOP politics, not an abberration.

Ducks by Kate Beaton - amazing graphic memoir by the Hark, A Vagrant writer about working in the Alberta oil sands to pay off her student debt. An incredible portrait both of what it’s like growing up working class in a small town and the sacrifices that entails and the trauma of being one of the few women in a very harsh working environment.

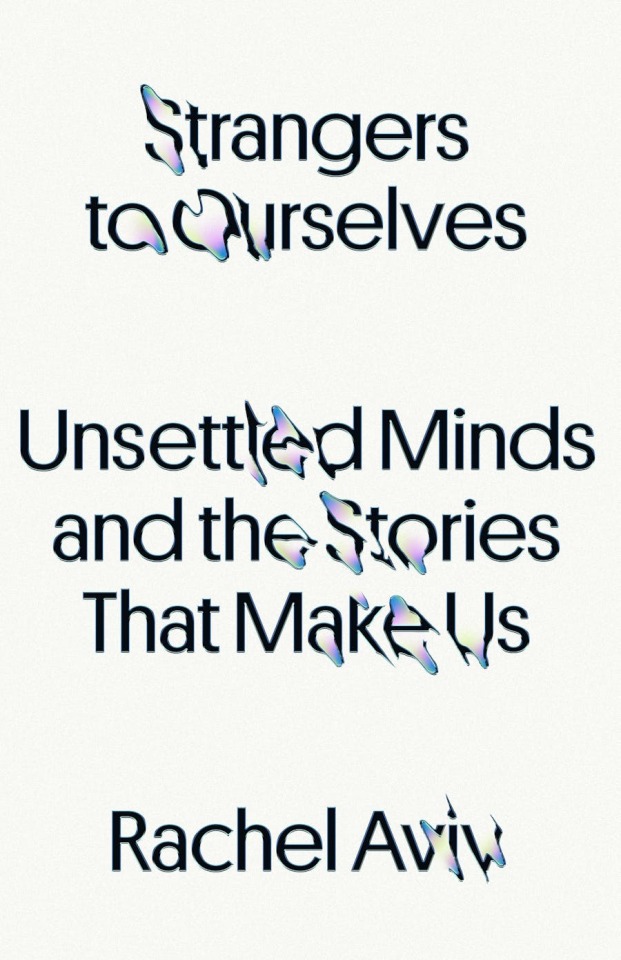

Strangers to Ourselves by Rachel Aviv - fascinating series of vignettes by one of my favorite New Yorker writers exploring different people’s perceptions of mental illness and how we can become trapped in our own narratives.

By Hands Now Known: Jim Crow’s Legal Executioners by Margaret A. Burnham - this was hard to stomach because of the depth of cruelty it described but is well worth reading to understand just how all-encompassing a reign of terror Jim Crow was for black Southerners.

Getting Me Cheap: How Low Wage Work Traps Women and Girls in Poverty by Amanda Freeman and Lisa Dodson - Damning Indictment of how this country treats poor people and how women and girls, particularly single mothers, bear the worst burden.

We Need to Build: Field Notes for a Diverse Democracy by Eboo Patel - I would get every left-of-center person to read this if I could.

Honorable mentions: His Name Is George Floyd by Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa and Bad Jews by Emily Tamkin.

Best fiction (non new)

I ended up reading a lot of fiction by 20th century European authors, and particularly loved The Radetzky March by Joseph Roth, The Post-Office Girl by Stefan Zweig, Everything Flows by Vassily Grossman and The Years by Annie Ernaux. Reading these felt like getting a little tour of the century, particularly of how radically modern Europe was shaped by WWI and WWII.

Boy Parts by Eliza Clark and In a Lonely Place by Dorothy Hughes were my two other favorites, and are of a pair in that they’re refreshing (despite being over 60 years old in one case) takes by woman writers on a specific style of novel and make incredible use of an unreliable narrator.

Best nonfiction (non new)

I continued to read a lot of nonfiction about abortion and most appreciated The Girls Who Went Away by Ann Fessler, which details the human cost of the “baby scoop” era and Beggars and Choosers by Rickie Solinger, which criticizes the shift from rights to choice-based language in discussions of reproductive politics.

I also really enjoyed Mark Lilla’s The Shipwrecked Mind about reactionary politics, which honestly felt like a better version of The Decadent Society and Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning by Cathy Park Hong, which was written before the pandemic and felt extremely prescient about a lot of the discourse of the past few years.

Best poetry

I didn’t read a ton of poetry that really grabbed me but I enjoyed Sherry Shenoda’s The Mummy Eaters, which explores the author’s Coptic Egyptian heritage. From previous years, I enjoyed Philip Metres’ Shrapnel Maps and Richie Hofmann’s Second Empire.

37 notes

·

View notes

Quote

History isn’t only ever measured by battles and massacres and prisons, but also by the incremental blood drip of the thinnest veins.

Jamil Jan Kochai, “Hungry Ricky Daddy” from The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories

#Jamil Jan Kochai#The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories#quote#fiction#short stories#2023 reads

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

@lesbiancassius' march reads

books (once again, so busy...)

Salvage the Bones, Jesmyn Ward - a beautiful, hardy book I've been meaning to read for years. I read this as an ebook but I wish I'd had it in my hand.

short fiction & poetry

Waste My Life, Hera Lindsay Bird - I love Bird's voice so very much.

life is great

it’s like being given a rare and historically significant flute

and using it to beat a harmless old man to death with

Jealousy, Hera Lindsay Bird

Leisure, Hannah, Does Not Agree with You (2), Hannah Gamble - loosely after Catullus.

articles

Interrogating the Shakespeare System, Madeline Sayet - on @goosemixtapes's suggestion - a good read for reckoning with the place of Shakespeare in education and theatre now.

Classical studies needs structural change, an interview with Dr. Dan-el Padilla Peralta

Playing Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, Jamil Jan Kochai

Bridges, Callista Pitman - beautiful.

tbr

The Great White Bard, Farah Karim-Cooper

Towards a Poor Theatre, Jerzy Grotowski (I own the most hilariously water-damaged copy of this book that I got for free on the side of the road.)

Scorched, Wajdi Mouawad

There is Violence and There is Righteous Violence and There is Death, or the Born-Again Crow, Caleigh Crow

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any book recommendations?

Actually, yes!

Dan Hicks’s The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence, and Cultural Restitution is fascinating, vital, and powerfully written.

I also recommend Jamil Jan Kochai’s collection, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories.

In terms of, like, novels… honestly, I haven’t read a novel I enjoyed in ages. I do really like the Benjamin January mysteries by Barbara Hambly.

I’m continually looking for novels that I might like… but a lot of what gets published now is just so badly written, with little-to-no editing, and it’s hard to read.

16 notes

·

View notes