#lifers

Photo

My 2 lifers for 2022: Yellow-Bellied Flycatcher & Short-Eared Owl

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

M E N T A L x #choosewisely #mentalhealth #chooseyourself #knowyourself #knowyourworth #lovehate #quote #quotes #quotestoliveby #quotestagram #quoteoftheday #quotesaboutlife #instaquote #life #lifer #lifers #lifelesson #lifestyle #lifestyles #beyourself #message #messages #ownit #melonheads #melonheadsknow #onetimeforthedreamers #onetimeforthelifers x @watermelonterrace @dolphintography @freddiegibbs #visionaryvandals #livelifevandalful (at Mental Health Matters) https://www.instagram.com/p/CplfX7NrFzU/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#choosewisely#mentalhealth#chooseyourself#knowyourself#knowyourworth#lovehate#quote#quotes#quotestoliveby#quotestagram#quoteoftheday#quotesaboutlife#instaquote#life#lifer#lifers#lifelesson#lifestyle#lifestyles#beyourself#message#messages#ownit#melonheads#melonheadsknow#onetimeforthedreamers#onetimeforthelifers#visionaryvandals#livelifevandalful

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Momus: The Art Creep Is Dead

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have returned to my Local H phase and im ENJOYING IT SO MUCH :) been a minute

1 note

·

View note

Text

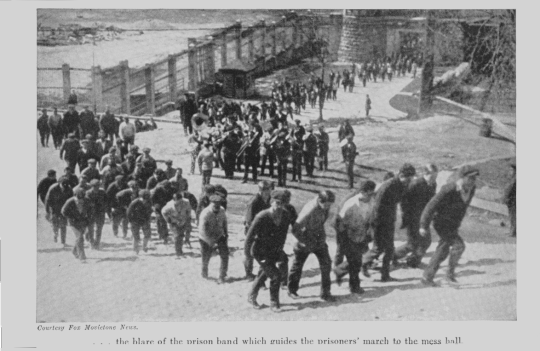

"By 1924, progressive prison reformers were openly lamenting the atrophy of public interest in the cause of humanitarian prison reform; two years later, many noted that this inattentiveness had turned to outright hostility toward a number of the foundational principles of progressive penology. That year, under the leadership of Republican Crime Commissioner, state Senator Caleb Baumes, the Republican-dominated New York state legislature breathlessly enacted twenty two crime bills that, together, had far-reaching implications for offenders and life in the state’s prisons. Popularly known as the "Baumes laws," the new legislation created new crimes, retrenched procedural protections for the accused, abolished the good-time system under which good behavior in prison reduced a convict’s sentence, reintroduced mandatory sentencing, and drastically raised maximum sentences for a number of serious crimes. (For example, the maximum sentence for first-degree robbery was raised from twenty years to life imprisonment and, for second-degree robbery, from ten to fifteen years). Most infamously, the Baumes laws strengthened the state’s 1907 habitual criminal law by providing that any person convicted of a fourth felony "shall be sentenced to life imprisonment without possibility of parole or commutation of sentence."

The passage of these laws had little, if any, appreciable impact upon New York’s supposed crime wave (although, according to an outraged Clarence Darrow, they contributed significantly to a national "hate wave" and constituted an egregious assault upon civil liberties). The laws did, however, play a catalytic and, in many ways, deeply ironic role in the history of legal punishment. In effectively abolishing indeterminate sentences and providing that upon a fourth conviction for felony crime a convict would automatically receive a life sentence without possibility of parole or commutation, the Baumes laws threw a large spanner into the disciplinary machinery of the prisons. As noted earlier, the logic of the new disciplinary system held that prisoners would render up obedience in exchange for earlier freedom and, in the meantime, the pleasures and releases afforded by movies, athletics, tobacco, and various other sublimating activities. The Baumes laws, however, challenged three of the principal presuppositions of this penology: namely, that all but a small minority of convicts would eventually leave prison; that no hardened core of embittered, hopeless "lifers" would accumulate in the prison; and that every prisoner, in theory at least, enjoyed the possibility of early discharge through good behavior. These were important structural preconditions for penal managerialism’s system of incentive; without them, convicts had much less reason to cooperate with the administration and far more incentive to rebel.

As well as tinkering with the incentive system of managerial penology, the Baumes laws breached a principle of justice dear to the hearts of prisoners: equality of sentencing (wherein the same crime got the same time, regardless of the convict’s record). As Warden Lawes understood very well, equality of sentencing, and more especially prisoners’ perception that the criminal justice system treated convicts more or less equally, was essential to the task of maintaining the good morale of the prisoners – and, hence, the good order of the prison. The "four strikes” law engendered the situation by which a person convicted of four burglaries would be automatically incarcerated for life without possibility of parole or commutation, whereas a person with a conviction for manslaughter (or even two previous convictions for manslaughter) would more likely serve a sentence of twenty years. This assault upon equality of sentencing prompted Lawes to complain to a reporter from the New York Times that the Baumes laws quite perversely provided robbers an incentive to kill their victims and plead guilty to what was now the lesser charge of manslaughter. The third problem posed by the Baumes laws was that their provision for longer sentences and mandatory lifetime sentences for fourth-timers threatened to trigger a rapid increase of the prison populations in prisons that were already putting two, and sometimes three, men in cells measuring just six feet by five feet. The Baumes’ laws seemed very likely to overfill the prisons; moreover, the surplus of prisoners would consist not in the usual run of convicts, but in an aggrieved and hopeless class of convicts who considered themselves profoundly wronged by the law.

Once the Baumes laws went into effect in July 1926, prison populations began to grow quite steeply and prison conditions began to degenerate. The initial source of the increase was not a rapid upswing in new commitments, but rather a decrease in the release rate, and people entering with longer sentences to serve: Fewer people were committed to New York’s state prisons and reformatories in 1927 than in 1926, but New York’s state prison population nonetheless increased quite steadily in the following years, as the first to be sentenced to life under the four strikes law began to trickle into the system. Every year after 1927, commitments to the state prisons increased dramatically. In 1928 and 1929, the population of the four main state prisons increased over eleven percent, or just over five percent per annum. Cellblocks that already held a full complement of prisoners overflowed: By 1929, New York’s male state prison population exceeded cell capacity by almost 1,000 men – or twenty percent – of the prisons’ capacity. Although, in and of itself, the increase in the sheer number of prisoners exerted considerable pressure on the prison order, the particular source of the surplus population was even more significant. Just as Lawes had warned, the prisons began accumulating miserable and volatile lifetime prisoners, and a larger mass of prisoners serving longer sentences for lesser crimes. At Sing Sing an influx of Baumes "lifers" increased the total number of prisoners serving life terms by sixty-five percent in just sixteen months. These were precisely the prisoners whom Lawes warned would have no hope for the future and who, in their mounting desperation, were likely to resist, escape, or even attempt to overthrow prison authorities.

Prisoners at Auburn and Clinton, the prisons to which the majority of repeat and lifetime convicts were committed, became increasingly restive in these years. Audacious escape attempts multiplied: A train-load of men being transferred out of overcrowded Sing Sing to Clinton in late 1927 attempted a mass break in transit (the attempt was foiled). The same year, Clinton authorities intercepted a cache of weapons, ammunition, and maps intended for a group of prisoners, and learned of plans for a large-scale prison break. In another spectacular, if equally unsuccessful, escape attempt, three convicted felons held in Manhattan’s "Tombs" jail used smuggled pistols to shoot their way to freedom; along the way, the warden and head keeper were shot dead, and two of the prisoners turned their weapons on themselves rather than face trial under the new laws. The rate of smaller scale escape attempts also inclined – both at the state prisons and at police jails, where accused offenders awaited trial under the new sentencing laws or transfer to a state prison.

Under the strain, the critical mechanisms of managerial prison discipline – sublimation and the activation of a convict’s desire to be free – threatened to jam. The respective state prison wardens took immediate steps to head off trouble: All scaled-up security and most rolled back privileges. In the midst of the statewide spate of escape attempts, the warden of Great Meadow abolished the honor league and put the convicts to work building a high wall around that previously low-security prison. At Auburn, warden Edgar S. Jennings abandoned the basic managerial approach and began to crack down on various prisoner-organized activities. Anxious to assert his authority, Jennings moved, in 1927, to cancel the established celebrations surrounding various national and ethnic holidays in the prison. Failing to recognize that such affairs could be restructured in such a way as to stabilize rather than undermine the prison order, Jennings insisted they were inherently disruptive, unruly events: "The Irish-Americans wish to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day; the colored men, Emancipation Day; the Italians, Columbus Day; the Polish, a Polish Day; and the Hebrews, a special feast day," he exclaimed in an exasperated memo to the Superintendent of Prisons in 1927. "The rivalry between those few different groups to have a more successful performance, bigger acts, and more entertainment has developed a condition that is very unsatisfactory," he went on: The celebrations had to be curtailed. The warden proceeded to abolish half-holidays, lock-down the prisoners in their cells on Saturday nights, cancel special suppers, reinstate the punishment cells, and suspend various privileges. As warden Jennings cracked down, prisoners began defying orders, the warden punished alleged troublemakers with ever longer periods of isolation in the punishment cells, and the keepers turned against both the league and a warden who seemed incapable of reining in the prisoners. Clinton’s warden rolled back privileges and segregated suspected troublemakers in the punishment cells.

At Sing Sing, Lewis E. Lawes took a different tack. Like his colleagues up-state, he quietly tightened security at the prison (chiefly, by suspending visiting, reinforcing the prison wall, and mounting machineguns on the watchtowers). But, at the same time, he stepped up his program of morale-building. Lawes redoubled his efforts to demonstrate his responsiveness to the prisoners and their needs. As well as maintaining established programs, he gave the entire prison a special chicken dinner, motion pictures, and live music on Thanksgiving; likewise, on Christmas day, he and his wife provided the men with movies, a special meal, and small "favors" and gifts. At the request of one "lifer" he ordered the stars and stripes hoisted within sight of the cellblock, in honor of the 300-odd Great War veterans who resided there. He also extended the new psychiatric program at the prison, describing the program as a great asset to prison administration. Finally, he made a number of public statements in which he made it clear, not only to the general public but to the prisoners, that he was unequivocally opposed to the Baumes laws and that he felt considerable empathy for the convicts. All men, including prisoners, had their breaking point, Lawes declared in a 1928 radio address on Collier’s hour (which was broadcasted live to the men of Sing Sing): All were subject to temptation.

The deteriorating situation in the prisons came to a head in the summer of 1929. At Clinton prison, on July 22, 1929 (almost exactly three years after the Baumes laws had gone into effect), 1,300 prisoners attempted to storm the walls and burn down the buildings. Before a hastily convened force of keepers and volunteers restored order, three prisoners were shot dead and dozens more, peppered with buckshot. Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt indicated, following the Clinton rebellion, that no executive action was needed. However, within days of the Clinton rebellion, the escalating power tussles at Auburn erupted into open conflict. A full-scale uprising broke out. Auburn prisoners rioted for several days, razing the wood and furniture shops, foundry, dye house, store house, and commissary and seriously damaging five other prison buildings. Order was restored only after the National Guard was called out. Realizing that these riots were probably not isolated incidents, after all, Roosevelt called for an immediate and wide-ranging investigation of the prisons, and for a review of the Baumes laws (which he strongly inferred were responsible for the recent unrest in the prisons).

Using a technique he would later put to use as President of the United States, Roosevelt convened a series of “parleys” at his Manhattan residence, calling together a wide array of experts, including prison wardens, members of the National Committee on Prisons & Prison Labor, and criminologists, to discuss the prison situation. As the investigation got underway in earnest, Auburn prisoners acted a second time to register their frustration and anger at the Baumes laws. In December 1929, a handful of Auburn prisoners rebelled once again, this time taking warden Jennings hostage and calling for the release of their comrades from the punishment cells. When the authorities refused to cooperate, the prisoners put that marvelous technology of penal managerialism – the radio system – to work, broadcasting a general call to riot, and successfully precipitating a second, full-fledged prison uprising. The National Guard was called out once more. By the time order was restored, the principal keeper and eight convicts were dead, four guards and two convicts were seriously wounded, and dozens of convicts and guards had been gassed. (Warden Jennings survived).

...

Notably, convicts at the most infamous of American prisons – Sing Sing – did not riot. Although it was the case that Sing Sing had not borne the full brunt of the four strikes laws (largely because it received mostly shorter-term first and second-time offenders) it was, nonetheless, more overcrowded than at any other point in its history, and it did have a small, but rapidly growing, population of Baumes "lifers." Like his colleagues, Lawes had tightened security as unrest among the prisoners had mounted after 1926. But, unlike the others, Lawes had extended and reinforced the morale-building disciplinary system and sought, at every turn, to shore up the "square deal" between prisoners and keepers.

Upon hearing rumors that Sing Sing prisoners might follow Auburn’s example and riot, Lawes deftly deployed a combination of force and empathy to maintain control of Sing Sing. He immediately talked with the Sing Sing convicts and solicited their grievances. While consulting with his wards, he also made it clear that any collective action or protest on the convicts’ part would be met with swift and certain repression. An overwhelming show of force punctuated this threat: Within hours of the December uprising at Auburn, three companies of the National Guard went on alert at Sing Sing, a small U.S. naval vessel sailed up the Hudson from New York City, and three more Gattling machine guns appeared on the high wall of the prison. As convicts witnessed this show of force, Lawes quietly suspended the Mutual Welfare League’s annual Christmas show on the grounds that a large gathering of convicts might be volatile. As Lawes later told the story, when the league’s leaders voted to resign in protest and rumors began circulating to the effect that a riot was imminent, he accepted their resignations and then promptly informed the prison population that the former organizers had resigned and were on their way to Clinton prison. But even at this point, Lawes did not abolish the league or institute a prisonwide crack-down, as Jennings had done at Auburn. Rather, he worked with the league’s new leaders (who quietly "agreed" with Lawes that the show, indeed, ought to be cancelled, after all) to calm the prison. Rumors of imminent riot subsided. Some sixteen years after the scandalous rebellion of 1913, and as prisons around the state and in other parts of the country erupted in protest, Lawes had enforced the good order of Sing Sing. Even more critically, he had been seen to have done so.

Rather than undermining the penal managerial model of imprisonment, the riots of 1929 indirectly facilitated its consolidation and extension throughout New York’s state prison system. That the Baumes laws had very likely precipitated the Auburn and Clinton prison riots was not lost on Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt; nor did Roosevelt fail to notice Sing Sing’s relative calm and Lawes’s apparently adept handling of the unrest there. In a confidential memorandum to Lawes, Roosevelt sought his advice and, in particular, his views on the Baumes laws’ impact on prison order. A series of official investigations further called into question both the efficacy and the justice of the Baumes laws and cast a very positive light on Lawes and his well-worked-up model of prison administration.

Following the December riot at Auburn, a hastily convened commission headed by Colonel George F. Chandler (former Superintendent of the New York State Police) scrutinized not only the actions of prisoners, but prison conditions and the conduct of the warden, guards, police, and troopers. In his report, Chandler condemned Auburn as an overcrowded prison full of ill-disciplined, underfed convicts and declared that a small group of "desperate" longterm convicts (of the sort generated by the Baumes laws) had taken over the Mutual Welfare League (MWL) and were more or less running the prison. His objection, critically, was not that the convicts were attending entertainments but that the warden had suffered the MWL to become a thuggish gang under the tutelage of the long-term men. (Chandler wrote: "These League officers have police powers, administer punishments, order privilege taken away or granted, run entertainment once or twice a year for which they collect money from the general public who attend, and run a baseball club where male outsiders may attend." Moreover, the convicts ran the telephone switchboard, assisted in mail handling and the cleaning of the offices, guard rooms, and hallways, which, Chandler objected, compromised security.) He concluded by recommending that the overcrowding of the prison be relieved and the Auburn MWL, abolished.

In a separate investigation, Joseph M. Proskauer, an associate justice of the Supreme Court of New York, affirmed these findings but was far more explicit in placing the blame for the riots squarely on the shoulders of the Baumes laws. Proskauer urgently recommended that Governor Roosevelt undertake "fundamental and drastic reform" of the state’s penal system. The Superintendent of Prisons, Raymond Kieb, also criticized the Baumes laws, and recommended the restoration of compensation time. He publicly declared: "(i)t was the strongest instrument the office had for the preservation of law and order in the prisons, as each [convict] knew that behavioristic [sic] deviation led to time forfeiture and delayed the date the prisoners might be granted the privilege of again being free." Finally, the National Society of Penal Information (whose membership was composed of veteran progressive reformers) issued a report laying the blame for the first two New York rebellions on the new sentencing laws, the curtailment of the good-conduct system of early release, and the retrenchment of parole.

In 1930, Roosevelt proceeded to act on these recommendations. He and the Superintendent of Prisons consulted with the wardens about how best to rebuild discipline at Auburn and in the system more generally: Warden Lawes’s Sing Sing was to serve as the basic model of reform. Notably, prison industries – which, just a few years earlier, had been the object of intensive discussion – were given very little emphasis. In announcing the appointment of two prison planning committees (one on the "segregation" of various classes of prisoners and one on prison industries), Roosevelt indicated that putting prisoners to productive labor would most likely not be part of the solution: Noting that "an idle prisoner becomes a brooder and only too often eventually a plotter" he suggested that "trade schools rather than ... factories" might be established in the prisons. Instead, New York’s prison reforms concentrated on segregating various classes of prisoners, repealing the Baumes sentencing laws, and, slowly but surely, applying the principles of Lawes’ managerial penology across the entire state prison system. Roosevelt announced a $30 million program for the improvement of prison conditions, athletics and exercise programs, education, manual training, and the systematic segregation of various classes of prisoners. Notably, when Roosevelt discussed the program he remained silent on the topic of prison industries.

Over the next few years, the principles of the sublimation of prisoners’ emotions through a variety of mostly nonlaboring activities, the privilege system, and the occasional show of uncompromising force, were generalized to the entire state prison system. Although, at Auburn, the MWL was abolished (as per Roosevelt’s request), the recreational and educational activities its members had organized were eventually reinstituted under the auspices of the state, much as Chandler had recommended. On Lawes’s insistence that good food was an important "aide to morale," the quality of prison rations was improved all round. Psychiatrists were hired for each prison and proceeded to play an important role in the assessment of those convicts thought to pose a risk to the prison’s security. Sing Sing psychiatrist, Bernard Glueck’s, taxonomy of mental health was adapted to these ends; in all the prisons, the psychiatrists’ primary task was that of adapting petulant, troublesome, or depressed convicts to prison discipline and identifying for segregation (or exile to Clinton) those deemed to be security threats. Penal managerialism’s need for guards who would resort to psychological, rather than corporeal, means of managing prisoners, was implicitly recognized in the planning and execution of the state’s first guard training programs and the New York State Training School for Guards at Wallkill prison (opened in 1936). Finally, in 1931, at the recommendation of the State Commission of Correction, and with the vocal support of Lawes and Roosevelt, the New York legislature repealed several of the Baumes laws: Most critically, lawmakers reinstituted one of the cornerstones of managerial penology – the good-time compensation plan, under which good behavior was to be rewarded by early release. A year later, Roosevelt signed into law a bill that repealed the mandatory life sentence that another Baumes law imposed on fourth-time offenders: Persons convicted of a fourth felony were now subject to a minimum sentence of fifteen years in prison rather than the mandatory sentence of life.

As part of this general overhaul of the state prison system, Roosevelt also established a State Commission on Prison Administration and Construction, charging it with the task of planning and building six new prisons. The state’s second great wave of prison building soon followed, and in four years, five new state prisons were opened (Attica, Bedford Hills, Coxsackie, Wallkill, and Woodburne). All were to be administered according to much the same managerial principles prescribed for the other prisons of the state. Critically, prison labor was not to be used in the construction of these new facilities: William Green, the President of the AFL, successfully lobbied New York state, and the federal government, to restrict the use of penal labor in public works on the grounds that convicts were provided with "food, clothing, and shelter" while, as the Great Depression wore on, free labor was going without. Prisons were "public works" and as such, it was agreed that free labor, rather than convict labor, should build them."

- Rebecca M. McLennan, The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776-1941. Cambridge University Press, 2008. McCormick, p. 450-459

The photo shows prisoners at Sing Sing marching to the mess hall, from Lewis E. Lawes, Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing. New York: A. L. Burt Company, 1932, p. 178.

#sing sing prison#penal reform#penal modernism#managerialism#prison riot#causes of prison riots#crisis of imprisonment#new york prisons#classification and segregation#tough on crime#baumes laws#history of crime and punishment#academic quote#reading 2023#lifers#severe sentencing#lewis lawes#prison construction#auburn prison#clinton prison#new york history#prisoner resistance#convict revolt

0 notes

Text

It's the notion that your body is never gonna change. The baby fat that's hiding in your cheeks won't fade. And you're not sure why, but when you leave the house you circle the block to cry. Do you think that we'll outrun it? Get past the pain of simply being? Every time you want out of your body, or can't get your head around this dream. You swore you loved it more when you couldn't guess the end. It's never adding up, but don't write yourself out of the equation.

hi why is this such a trans mood

#Bandcamp#the first time i heard this i felt so called out istg#how dare you write a song that resonates with me so much#spanish love songs#lifers#no joy#audio

1 note

·

View note

Text

Atlantic Ocean, north of Cuba, approx. 21.321066 by -75.892584 (Carnival Horizon cruise ship)

October 23, 2023, 1226

83'F, sunny, moderate wind

Species observed:

Atlantic flyingfish (x)

Brown booby*

Schools of flying fish! Usually 1-3 at a time but more than a dozen on occasion. Seem to be moving away from the ship, soaring for five seconds or so before smashing into a wave or dropping into the water. Longest air time observed was about 7 seconds. Four obvious fins, translucent and spread wide. Body is darker, blue or silver. Size is hard to judge due to distance but they look to be about hand-sized, maybe a little bigger.

Note: later research confirms these are Atlantic flyingfish, 10 inches long on average, with the ability to glide for 10-40 feet out of the water to evade predators. They are indeed blue or green dorsally and silver ventrally.

Brown booby flew alongside the ship for several minutes banking side to side, finally peeled off and flew low over the water. Defecated, landed in the water for only a second, and then took off again, keeping low to the water until it eventually fell behind the boat.

0 notes

Text

I've been curating some of these things and I think it's time to let them loose into the world. My hope is that at least one of them is funny

#Yes I just make these on the side whenever I find anything I think is funny and then hoard them#trafficblr#mcyt#am I gonna tag all the lifers for this. am I#sigh.ok some of them#zombiecleo#bad boys#jimmy solidarity#joel smallishbeans#ethoslab#scott smajor#geminitay#skizzleman#goodtimeswithscar#boat boys#not meant to be shippy Im just trying desperately to be a little funny#shiny duo#idk what else ur supposed to tag in these#bdoubleo#shak's shitpost

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

68K notes

·

View notes

Text

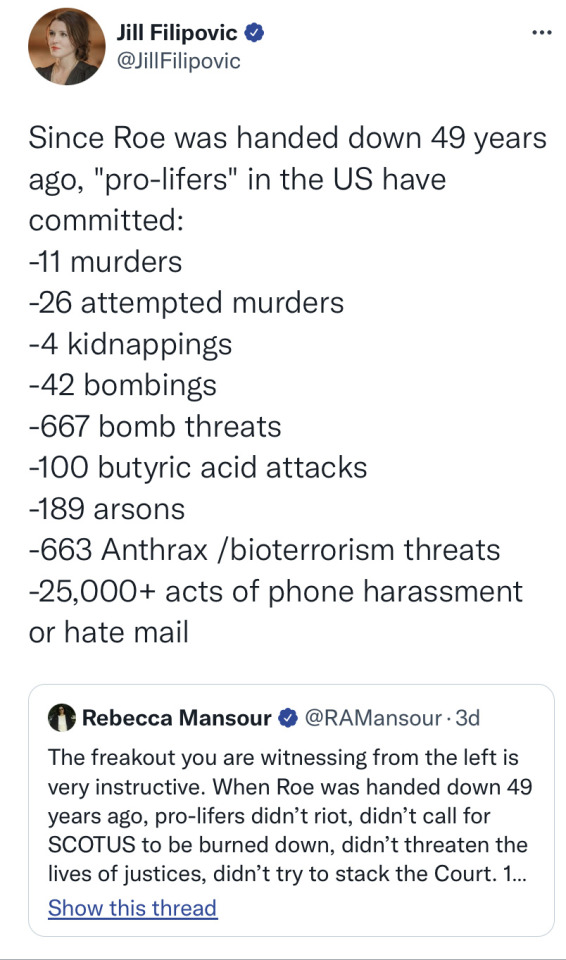

ppl being like “abortion is okay only if you took all the “correct” measures first or if you were impregnated non-consensually” SHUT UP! abortion for “sexually promiscuous” people and sex addicts and ppl you call sluts and whores and people who have one-night stands and every single person who had sex because they felt like it! you do not have to reach a quota of suffering to “deserve” an abortion. abortion is not something you earn. abortion isn’t a moral thing like you protestants like to think it’s a fucking right and everyone deserves access to it and they don’t have to prove that they deserve it. pregnancy is not a punishment for sex and every single person deserves the right to terminate a pregnancy regardless of how they became pregnant. shut up

#i am angry#because it’s my body and i do not owe pro lifers access or authority over my womb#abortion#pro choice#text post#top posts#10k#15k#20k#25k#30k#35k#40k#45k#50k

53K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bʀᴏᴋᴇɴ Hᴇᴀʀᴛ = Fɪxᴇᴅ Vɪsɪᴏɴ x #brokenheart #vision #freddiegibbs #knowyourself #knowyourworth #lovehate #quote #quotes #quotestoliveby #quotestagram #quoteoftheday #quotesaboutlife #instaquote #life #lifer #lifers #lifelesson #lifestyle #lifestyles #beyourself #message #messages #ownit #melonheads #melonheadsknow #onetimeforthedreamers #onetimeforthelifers x @watermelonterrace @dolphintography @freddiegibbs #visionaryvandals #livelifevandalful (at The Vision) https://www.instagram.com/p/CoQaT1Vp7Rd/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#brokenheart#vision#freddiegibbs#knowyourself#knowyourworth#lovehate#quote#quotes#quotestoliveby#quotestagram#quoteoftheday#quotesaboutlife#instaquote#life#lifer#lifers#lifelesson#lifestyle#lifestyles#beyourself#message#messages#ownit#melonheads#melonheadsknow#onetimeforthedreamers#onetimeforthelifers#visionaryvandals#livelifevandalful

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Stinking Lizaveta - Shock

0 notes

Text

Backshots W/ Monster Ass

casino rentals jacksonville fl

Big booty ass latina

Two busty milf share a big cock

MILF Eva Notty licks Lillys wet pussy

Sexy Nepali Girls Upskirt

masturbacion en casa

EBONY BBW EATING OUT SEXY WHITE STUD

Chilenita rica las condes

Assfucked babe sucking dildo before sex

#pasquilant#Bulan#Utgard#lifers#Voyt#hyperintelligently#saily#overurged#jant#sofas#repatriate#farles#semipedantically#arrow-grass#docoglossan#ornamentation#pennyworth#levees#anoestrus#messycore

0 notes

Text

cedar saturday :-)

#after i posted him on instagram i saw a giant flock of bohemian waxwings for the first time#wrong waxwing but a lifer so i'll take it#cedar waxwing#bird artist#bird art#nature#nature art#illustration#artists of tumblr#artists on tumblr

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Lifers #HighRollers #JFA #AZPX #TheChief 160 years of skateboarding and friendship 📷 Colin Choy (at Tempe Skatepark) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cj_tcXLplp2/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Carnival Horizon cruise: Miami, FL; Ocho Rios, Jamaica; George Town, Cayman Islands; San Miguel de Cozumel, Mexico

October 22-28, 2023

New species observed:

Florida

White ibis

Laughing gull

Boat-tailed grackle

Jamaica

Magnificent frigatebird

Greater Antillean grackle

Little blue heron

American redstart

Royal tern

Cayman Islands

West Indian whistling-duck

White-winged dove

Northern mockingbird

Mexico

Tropical mockingbird

Cozumel emerald

Bananaquit

Tropical kingbird

Yellow-throated warbler

Black vulture

Great egret

At sea

Brown booby

0 notes