#linguistic diversity challenge: the region edition

Text

Best Business Translation Services: Expand Your Global Reach

We all are interconnected and expanding your business globally is more achievable than ever. However, one of the key challenges businesses face when entering new markets is overcoming language barriers. This is where the best business translation services come into play, ensuring your message is accurately conveyed across different languages and cultures.

Why You Need Business Translation Services

Effective communication is the cornerstone of any successful business operation. When expanding into international markets, it's crucial to convey your brand's message, values, and information accurately. Miscommunication can lead to misunderstandings, damaged reputation, and lost opportunities. Professional business translation services help mitigate these risks by providing accurate and culturally appropriate translations.

What to Look for in a Business Translation Agency

Choosing the right business translation agency is essential for your global success. Here are some factors to consider:

Expertise and Experience:

Look for a company with extensive experience in your industry. An agency familiar with the specific terminology and nuances of your field will provide more accurate translations.

Quality Assurance:

Ensure the agency has a rigorous quality assurance process. This includes multiple rounds of editing and proofreading to eliminate errors.

Cultural Competence:

A good translation goes beyond literal word-for-word conversion. It should consider cultural differences and ensure the message is appropriate for the target audience.

Technical Capabilities:

For businesses dealing with technical documents, it's important to choose a translation service that can handle complex and specialized content.

Customer Service:

Reliable customer support and communication are crucial. The agency should be responsive to your needs and provide updates throughout the translation process.

Top Business Translation Services Provider In Dubai

Dubai is a major hub for international business, making business translation services in Dubai essential for companies operating in the region. The city's diverse population and strategic location make it a prime destination for global expansion. Whether you need legal document translation, marketing material localization, or technical content translation, there are several reputable agencies in Dubai that can meet your needs.

Leading Business Translation Companies in Dubai

Dubai Translation Services:

Known for their professionalism and accuracy, they offer a wide range of translation services tailored to the needs of businesses in Dubai.

Langpros:

Specializing in legal and financial translations, Langpros has a team of certified translators who ensure your documents are translated with precision.

Petra Legal Translation:

They provide high-quality legal translation services, crucial for businesses dealing with contracts and legal documents in multiple languages.

The Role of Business Translation Professionals

Business translation professionals play a vital role in ensuring your global communications are clear and effective. These experts have a deep understanding of both the source and target languages, as well as the cultural nuances that impact how messages are received. Their expertise helps avoid misunderstandings and ensures your brand's message is consistent across different markets.

Qualities of Effective Business Translation Professionals

Linguistic Expertise: Mastery of both the source and target languages.

Subject Matter Knowledge: Familiarity with the industry-specific terminology and concepts.

Cultural Awareness: Understanding of cultural differences that affect communication.

Attention to Detail: Commitment to accuracy and quality in every translation.

Conclusion

Expanding your business globally requires clear and effective communication across different languages and cultures. The best business translation services provide the expertise and support needed to convey your message accurately and appropriately. By choosing the right business translation agency, leveraging the skills of business translation professionals, and utilizing comprehensive corporate translation services, you can overcome language barriers and achieve success in international markets. Whether you're looking for business translation in Dubai or anywhere else in the world, investing in professional translation services is a crucial step toward global growth.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Unlocking Opportunities with Kannada Translation Services

In an increasingly interconnected world, the demand for translation services has surged, reflecting the need for effective communication across diverse linguistic landscapes. Among the plethora of languages, Kannada holds a significant place as one of the major languages spoken in India, particularly in the state of Karnataka. To cater to this growing demand, professional Kannada translation services have emerged as a pivotal resource for businesses and individuals seeking to bridge language barriers.

Understanding the Importance of Kannada Translation

Kannada, with its rich literary heritage and cultural nuances, presents unique challenges and opportunities in translation. Whether you're a business looking to penetrate the regional market or an individual seeking to communicate effectively with Kannada speakers, the importance of accurate translation cannot be overstated. Mistranslations can lead to misunderstandings, misinformation, and lost opportunities, making it imperative to engage professional services that appreciate the subtleties of the language.

What Professional Kannada Translation Services Offer

Engaging a reputable Kannada translation service provider, such as those highlighted on PECTranslation, ensures several advantages:

Cultural Sensitivity: Professional translators are not just linguists; they are cultural ambassadors who understand the socio-cultural context of the language. This ensures that translations resonate with the target audience, reflecting local idioms and expressions.

Domain Expertise: Different industries have specific terminologies and jargon. A professional service will usually have translators specializing in various sectors, such as legal, medical, technical, and marketing, ensuring that the translated content is both accurate and relevant.

Quality Assurance: Established translation services typically implement a rigorous quality assurance process. This includes proofreading and editing by native speakers, which minimizes the potential for errors and ensures a high standard of quality.

Timely Delivery: In today's fast-paced business environment, time is of the essence. Professional translation services are equipped to handle large volumes of work and meet tight deadlines, allowing clients to release their content on schedule.

Confidentiality: With sensitive documents, confidentiality is paramount. Reputable translation services uphold strict privacy policies, ensuring that your information remains secure throughout the translation process.

Applications of Kannada Translation Services

The applicability of Kannada translation services is extensive. From translating marketing materials, legal documents, and medical reports to localizing websites and software, these services facilitate communication in a way that is not only linguistic but also cultural. Businesses aiming to expand their reach in Karnataka can use Kannada translations for advertisements, product descriptions, and customer support, enhancing their engagement with local consumers.

Conclusion

As businesses and individuals seek to navigate the complexities of globalization, professional Kannada translation services emerge as an invaluable ally. By ensuring clear communication and cultural relevance, these services unlock opportunities for growth and connection in one of India's most vibrant linguistic communities. Investing in quality Kannada translation services is not just about translating words; it’s about building meaningful relationships that transcend geographical and linguistic barriers.

For more information on Kannada translation services, visit PECTranslation to explore how your communication can reach its fullest potential.

0 notes

Text

Breaking Language Barriers: The Power of Website Translators

In an interconnected world where digital communication knows no boundaries, breaking language barriers has become more critical than ever. As businesses and individuals strive to reach a global audience, the need for effective communication across languages has led to the rise of innovative tools and technologies. The website translator is one such tool that plays a pivotal role in bridging linguistic gaps.

The Globalization Imperative

In the era of globalization, businesses are expanding their reach beyond borders, targeting diverse markets with unique linguistic backgrounds. As a result, the ability to communicate in multiple languages has become a competitive advantage. A website, serving as the digital storefront for many businesses, must be accessible to a global audience. This is where website translators come into play, offering a seamless solution to cater to the linguistic diversity of online users.

What is a Website Translator?

A website translator is a tool or solution designed to automatically translate the content of a website from one language to another. These translators utilize advanced algorithms and artificial intelligence to analyze and interpret text, providing users with a translated version of the content in real time. This dynamic approach allows websites to offer a multilingual experience, breaking down language barriers and making information accessible to a broader audience.

Benefits of Website Translators

Global Reach: The most apparent benefit of website translators is the ability to expand your audience globally. By offering content in multiple languages, businesses can connect with users from different regions, increasing their reach and potential customer base.

Enhanced User Experience: A user-friendly website caters to the preferences and needs of its visitors. A website translator enhances the user experience by allowing individuals to consume content in their preferred language, creating a more personalized and engaging interaction.

SEO Advantages: Search Engine Optimization (SEO) is a crucial aspect of online visibility. Website translators contribute to SEO efforts by making content accessible to a wider range of search queries in various languages. This can positively impact search engine rankings and increase organic traffic.

Cultural Sensitivity: Effective communication goes beyond literal translation. Website translators often take cultural nuances into account, ensuring that the translated content resonates appropriately with the target audience, thus fostering a sense of cultural sensitivity.

Cost-Effective Globalization: Traditionally, translating content has been a time-consuming and costly process. Website translators offer a cost-effective alternative, automating the translation process and significantly reducing the time and resources required for language localization.

Challenges and Considerations

While website translators bring immense value, it's essential to be mindful of potential challenges:

Accuracy Concerns: Automated translation may not always capture the subtleties and nuances of language accurately. Businesses should review and edit machine-generated translations to ensure accuracy and maintain the intended message.

Cultural Adaptation: Understanding cultural differences is crucial for effective communication. A one-size-fits-all approach may not suit certain markets, necessitating manual intervention to adapt content culturally.

Security and Privacy: Some website translators may involve sending data to external servers for processing, raising concerns about security and privacy. Businesses should choose reputable translation solutions that prioritize data protection.

Choosing the Right Website Translator

Selecting the right website translator is crucial for a successful multilingual strategy. Consider the following factors:

Accuracy and Quality: Look for a translator that provides accurate and high-quality translations. Some services offer human-reviewed machine translations for improved precision.

Language Support: Ensure that the translator supports the languages relevant to your target audience. A diverse language portfolio is essential for effective global communication.

User-Friendly Integration: Choose a translator that seamlessly integrates with your website's design and functionality. A user-friendly integration ensures a smooth experience for both website administrators and visitors.

Customization Options: Opt for a translator that allows customization of translations to align with your brand voice and tone. The ability to manually edit translations is valuable for maintaining authenticity.

Conclusion

In a world where diversity is celebrated, embracing linguistic differences is not just a choice but a necessity. Website translators empower businesses to communicate effectively with a global audience, fostering connections that transcend borders. While challenges exist, the benefits of breaking language barriers through innovative translation technologies outweigh the drawbacks. As we continue to navigate the digital landscape, the role of website translators remains pivotal in creating a more inclusive and connected online world.

Source: Breaking Language Barriers: The Power of Website Translators

0 notes

Text

English to Assamese Translation – Preserving Identity and Fostering Understanding

Language is the vessel that carries the essence of culture, history, and identity. As the world grows more interconnected, the need for effective communication between diverse linguistic communities becomes increasingly crucial. One such bridge that facilitates this exchange is English to Assamese Translation.

Assamese, an Indo-Aryan language, is primarily spoken in the Indian state of Assam and neighboring regions. It holds deep cultural significance and boasts a rich literary tradition that dates back centuries. English, on the other hand, is a global lingua franca, connecting people from different corners of the world. The process of translation between these two languages not only enables effective communication but also plays a pivotal role in preserving Assamese culture and heritage.

Preserving Assamese Identity:

Language is a window to the soul of a community, reflecting its beliefs, customs, and worldview. English to Assamese translation serves as a guardian, ensuring that the nuances and beauty of the Assamese language are not lost or diluted over time. Through translation, ancient folklore, traditional wisdom, and historical records find new life, passing on the essence of Assamese identity to future generations.

Reviving Traditional Literature:

Assamese literature has a long and illustrious history, boasting celebrated poets, writers, and playwrights. However, much of this treasure trove of knowledge remains inaccessible to non-Assamese speakers. Translation opens the doors to this world of literary excellence, allowing English readers to explore and appreciate the depth of Assamese literature.

Fostering Cross-Cultural Understanding:

Translation is a potent tool in fostering mutual understanding and respect between different cultures. It enables English speakers to grasp the unique worldview and traditions of the Assamese people. Moreover, it encourages Assamese speakers to engage with global ideas, literature, and advancements, enriching their own perspectives.

Bridging the Language Divide:

In a rapidly evolving world, the significance of English as a global language cannot be overstated. It is the language of science, technology, and diplomacy. English to Assamese Translation ensures that Assamese speakers can access the wealth of knowledge and information available in English. It bridges the language divide and empowers individuals to participate in the global discourse.

Challenges in Translation:

Translating between English and Assamese is a nuanced and delicate task. Assamese, like many Indian languages, is highly inflected and context-dependent. It possesses a unique script and cultural references that demand careful consideration during the translation process. Translators must strike a balance between staying faithful to the source text and making the content relatable to the target audience.

Enhancing Economic Opportunities:

Assam's geographical location as a gateway to Northeast India has made it an essential player in the region's economic development. Assamese translation plays a role in empowering the local workforce, as it enables individuals to access skill development resources, educational material, and business opportunities in their native language.

The Role of Technology:

Advancements in technology have revolutionized the translation industry. Automated translation tools can aid in basic translations, but human expertise remains essential in tackling the intricacies of language and culture. Hybrid approaches that combine machine translation with human editing have emerged, enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of the translation process.

Conclusion:

English to Assamese Translation is not just about converting words; it is about fostering a deeper appreciation for culture, literature, and ideas. It helps preserve the richness of the Assamese language and enables seamless communication between diverse communities. As we celebrate the beauty of languages and their ability to bring people together, let us recognize the profound impact of translation in shaping a more connected and harmonious world.

Source: https://wordpress.com/post/translationwala.wordpress.com/90

#English to Assamese Translation#English to Assamese Translate#English to Assamese#Assamese Translation#ইংৰাজীৰ পৰা অসমীয়ালৈ অনুবাদ#অসমীয়া অনুবাদ

0 notes

Text

The Quirky World of Translating Cultural Expressions

Idioms are colorful phrases that give a language flavor and character. They are strongly ingrained in culture and represent a community's distinct ideas, habits, and experiences. However, translating idioms is difficult since their meanings are frequently metaphorical and do not translate word for word. In this essay, we will dig into the intriguing realm of idioms and the complexities of translating unique cultural phrases while preserving their essence and linguistic appeal.

The Cultural Significance of Idioms:

Idioms are linguistic pearls that capture a community's cultural heritage and beliefs. They express common experiences, beliefs, and knowledge, providing insights into a culture's history, customs, and collective psyche. Idioms frequently draw on well-known symbols, analogies, or historical allusions that have strong significance within a particular cultural context.

Figurative Language and Literal Translation:

One of the most difficult aspects of interpreting idioms is their metaphorical character. Idioms are difficult to interpret word for word because they rely on metaphorical or symbolic connotations. Literal translations frequently result in misunderstanding or loss of meaning. Translators for translation company birmingham must use innovative ways to convey the metaphorical core of idioms while ensuring that the intended message is understood by the target audience.

Cultural Adaptation and Contextualization:

Idiom translation necessitates a thorough awareness of the cultural subtleties connected with them. Translators must evaluate the idiom's cultural background and identify analogous terms or cultural references in the target language that convey the same idea. Translators retain the integrity of idioms while assuring intelligibility and cultural relevance by adapting them to the target culture.

Preserving Humor and Wit:

Many idioms are laced with humor, wit, or wordplay that add an extra layer of charm to their meaning. Translators face the challenge of preserving the comedic effect and linguistic playfulness when translating idioms. They must explore creative solutions such as finding equivalent humorous expressions, using puns or wordplay, or employing idiomatic expressions in the target language to maintain the humor of the original idiom.

Exploring Variations and Equivalents:

Idioms often vary across languages, even if they convey similar concepts. Translators must be aware of regional variations and select equivalents that resonate with the target audience while remaining faithful to the spirit of the original idiom. Cultural consultation and collaboration with native speakers are invaluable in ensuring accurate and culturally appropriate translations of idioms.

Translating Untranslatable Idioms:

Some idioms are so firmly embedded in their cultural roots that straight translation is impossible. In such circumstances, translators must adjust or include explanatory footnotes or comments in order to express the spirit of the phrase. While it may disrupt the flow of the text, these additional resources provide readers with the background they need to understand the idiom's intended meaning.

Navigating Linguistic and Conceptual Differences:

Some idioms are so deeply ingrained in their cultural contexts that direct translation is difficult. Translators must edit or provide explanatory footnotes or comments in such cases to reflect the intent of the sentence. While it may interrupt the flow of the text, these additional resources give readers the context they need to comprehend the idiom's intended meaning.

Preserving Cultural Diversity and Communication:

Translating idioms is not only about language; it is about preserving cultural diversity and facilitating cross-cultural communication. By accurately translating idioms, translators enable individuals from different linguistic backgrounds to understand and appreciate the cultural richness and nuances embedded within these expressions. It fosters intercultural understanding and opens doors to shared experiences and knowledge.

Conclusion:

Idiom translation is an enthralling voyage into the quirky and vivid world of language and culture. It is necessary for translators to manage idioms' metaphorical, hilarious, and context-specific character while retaining their core and cultural significance. Translators use their skills to maintain cultural variety, encourage intercultural dialogue, and guarantee that idiomatic idioms continue to enhance our language tapestry.

0 notes

Text

The linguistic diversity challenge

South America and the Caribbean

-Old Tupi/ Nheengatu

The challenge

1. What is the language known as to linguists, and by the speakers themselves?

It’s known as old Tupi, classical Tupi and simply Tupi. In Portuguese it can also be spelled as Tupí. In Tupi it’s known as abáñeenga, meaning human language, ñeendyba, meaning common language, and ñeengatú. I’ll talk more about the term Nheengatu, how it can also be spelled, in the next topics. In Brazil the language can also be referred as Língua Geral Amazônica.

2. Where is the language spoken?

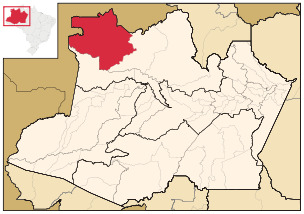

It is now considered an extinct language. The Modern Tupí, also known as Nheengatu is spoken by some indigenous groups in the state of Amazonas in Brazil. It is considered an official language in the municipality of São Gabriel de Cachoeira in the state of Amazonas. It is also spoken in parts of Colombia and Venezuela.

São Gabriel de Cachoeira in red and the state of Amazonas in red in the smaller map

3. How many speakers does the language have?

As I mentioned the language is extinct, but Nheengatu is still spoken by around 19,000 native speakers.

4. What are some of the languages relatives and is it part of a contact area?

The indigenous languages of Brazil can be divided in two main branches: Tupi and Macro-Jê. Not all indigenous languages fit in these branches though. In the tupi branch there is the Tupi-guarani family, in which the old Tupi language in included. Some languages of the Tupi-guarani family are: Tapirapé, Wayampi, Kamayurá, Guarani and Xetá.

5. Is the language written? If it is, with what script?

Originally the language is not written, but nowadays it can be written with the Latin alphabet (you know, the abc).

6. What is the language like grammatically?

Keep in mind that it’s an extinct language and it had to be reconstructed, so some elements were probably lost. Tupi was an agglutinative language, meaning it’s possible to form new words by putting together morphemes (morphemes are not the same as a word, but the bits that form a word, like prefixes and suffixes). Japanese is also considered an agglutinative language but English is not.

All verbs are in the present tense and are not conjugated for tense or mode, only for person. The gender of words were marked by adjectives. The nouns can be separated in higher that describes things related to human beings or spirits and lower nouns that describe animals and inanimate objects. To show this differences prefixes were attached to the words. Tupi used the subject-object-verb order.

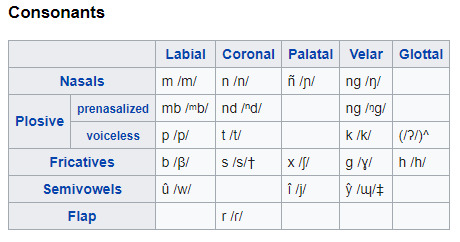

7. What is the language like phonologically?

Nheengatu

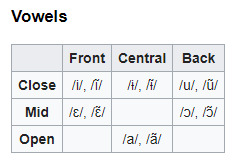

And here a comparison between Nheengatu and Old Tupi

The personal pronouns I, you (s.), he she, we (exclusive and inclusive), you (pl.), they.

8. What you choose the language?

I chose this language because of it’s importance to Brazilian history, culture and language. It influenced Brazilian Portuguese and some of the words we use currently come from Tupi.

#linguistic-diversity-regions#linguistic diversity challenge#linguistic diversity challenge: the region edition#mine#tupi#old tupi

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sekhukhune I[a] [b](Matsebe; circa 1814 – 13 August 1882) was the paramount King of the Marota, more commonly known as the Bapedi, from 21 September 1861 until his assassination on 13 August 1882 by his rival and half-brother, Mampuru II. As the Pedi paramount leader he was faced with political challenges from boer settlers, the independent South African Republic (Dutch: Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek), the British Empire, and considerable social change caused by Christian missionaries.

Sekhukhune was the son of Sekwati I, and succeeded him upon his death in 20 September 1861 after forcibly taking the throne from his half-brother and the heir apparent Mampuru II. His other known siblings were; Legolwana, Johannes Dinkwanyane, and Kgoloko. Sekhukhune married Legoadi IV in 1862, and lived at a mountain, now known as Thaba Leolo or Leolo Mountains which he fortified. To strengthen his kingdom and to guard against European colonisation, he had his young subjects work in white mines and on farms so that their salaries could be used to buy guns from the Portuguese in Delagoa Bay, as well as livestock.

Sekhukhune fought two notable wars. The first war was successfully fought in 1876, against the ZAR and their Swazi allies. The second war, against the British and Swazi in 1879 in what became known as the Sekhukhune Wars, was less successful.

Sekhukhune was detained in Pretoria until 1881. After a return to his kingdom, he was fatally stabbed by an assassin in 1882, at Manoge. The assassins are presumed to have been sent by his brother and competitor, Mampuru II.

The Pedi /pɛdi/ or Bapedi /bæˈpɛdi/ (also known as the Northern Sotho or Basotho ba Leboa and the Marota or Bamaroteng) – are a southern African ethnic group that speak Pedi or Sepedi, a dialect belonging to the Sotho-Tswana enthnolinguistic group. Northern Sotho is a term used to refer to one of South Africa's 11 official languages. Northern Sotho or Sesotho sa Leboa consist of 30 dialects, of which Pedi is one of them.

Some clans in tribes that speak variations of Northern Sotho can be traced back to the Kalanga-Tswana-Sotho group originating from earlier states such as Great Zimbabwe and Butua

The Pedi were the first of Sotho-Tswana peoples to be called Basotho, the name is derived from Swazi word uku shunta which referred to their clothing style, the Pedi took the name with pride and other similar groups began to refer to themselves as Sothos

Proto-Sotho people migrated south from the great lake region in east Africa making their way along with modern-day western Zimbabwe through successive waves spanning 5 centuries with the last group of Sotho speakers, the Hurutse, settling in the region west of Gauteng around 16th century. It is from this group that the Pedi/Maroteng originated from the Tswana speaking Kgatla offshoot. In about 1650 they settled in the area to the south of the Steelpoort River where over several generations, linguistic and cultural homogeneity developed to a certain degree. Only in the last half of the 18th century did they broaden their influence over the region, establishing the Pedi paramountcy by bringing smaller neighboring chiefdoms under their control.

During migrations in and around this area, groups of people from diverse origins began to concentrate around dikgoro or ruling nuclear groups. They identified themselves through symbolic allegiances to totemic animals such as tau (lion), kolobe (pig) and kwena (crocodile).

The Marota Empire/ Pedi Kingdom[edit]

The Pedi polity under King Thulare (c. 1780-1820) was made up of land that stretched from present-day Rustenburg to the lowveld in the west and as far south as the Vaal river.[9] Pedi power was undermined during the Mfecane, by Ndwandwe invaders from the south-east. A period of dislocation followed, after which the polity was re-stabilized under Thulare's son Sekwati.

Sekwati succeeded Thulare as paramount chief of the Pedi in the northern Transvaal (Limpopo) and was frequently in conflict with the Matabele under Mzilikazi, and plundered by the Zulu and the Swazi. Sekwati has also engaged in numerous negotiations and struggles for control over land and labor with the Afrikaans-speaking farmers (Boers) who had since settled in the region.

These disputes over land occurred after the founding of Ohrigstad in 1845, but after the town was incorporated into the Transvaal Republic in 1857 and the Republic of Lydenburg was formed, an agreement was reached that the Steelpoort River was the border between the Pedi and the Republic. The Pedi were well equipped to defend themselves though, as Sekwati and his heir, Sekhukhune I were able to procure firearms, mostly through migrant labor to the Kimberley diamond fields and as far as Port Elizabeth. The Pedi paramountcy's power was also cemented by the fact that chiefs of subordinate villages, or kgoro, take their principal wives from the ruling house. This system of cousin marriage resulted in the perpetuation of marriage links between the ruling house and the subordinate groups, and involved the payment of inflated bogadi or bridewealth, mostly in the form of cattle, to the Maroteng house.

#sekwati#sekhukhune#african#brownskin#brown skin#tunisia#zulu#swazi#mzilikazi#matabele#boers#pedi#pedi people#pedi ethnic group#kemetic dreams

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Q&A with Candice Whitney and Barbara Ofosu-Somuah, editors/translators of “Future. il domani narrato dalle voci di oggi,” edited by Igiaba Scego

A few weeks ago we announced on the WiT Tumblr an upcoming program at Casa Italiana NYU, “Stories Without Borders: A Conversation with Igiaba Scego,” hosted by Candice Whitney and Stefano Albertini, which you can watch here on YouTube. In an engaging and wide-ranging conversation, Scego talked about Italy’s colonial past in Africa, racial politics and systemic racism in Italy, the need for diversity in Italian publishing, and her reactions to the killing of George Floyd. Scego also discussed her reasons for editing the groundbreaking anthology of writings by AfroItalian women, Future. il domani narrato dalle voci di oggi [Futures. Tomorrow Narrated by the Voices of Today], published in 2019, which co-host Candice Whitney is currently translating with Barbara Ofosu-Somuah. (Candice is on the left and Barbara on the right in the photo above.) I followed up with Candice after watching the event to inquire about the Future anthology and about the translation project (which is currently seeking a publisher). Over several emails in July she and Barbara shared with me more details about the anthology and its writers, their personal encounters with Italy and the Italian language, and their commitment to creating a space for AfroItalian women writers in the English-language literary world.—Margaret

How did the Future anthology originate?

Candice Whitney and Barbara Ofosu-Somuah: Igiaba Scego, historian, journalist, fiction writer, and activist, wanted to create a text that acknowledges the future of Italy. The nation’s colonial legacy has shaped its national identity, citizenship laws, and how it relates to Blackness. For example, immigrants and their children, regardless of if they are born and/or raised in the country, are still othered as foreigners due to lack of citizenship reform.

A small publishing house in Florence, Italy, effequ, reached out to Scego to curate an anthology about migration. She had already edited and worked on influential anthologies related to migration, such as Italiani senza vocazione (Edizioni Cadmo, 2005). Ubah Cristina Ali Farrah, whose literary work connects the present day to the experiences of Somali relatives who moved to Italy, is an example of an artist that Scego collaborated with and admires. However, Scego wanted to pursue a different focus for effequ.

Reflecting on the double-consciousness of her life, specifically experiencing migration through the memory of her parents and living in Italy, Scego wanted to read and share perspectives of women similar yet different from her. The concept of Future was born from this idea. She chose to incorporate perspectives from writers of different generations, and from large and small cities across the nation.These authors write across genres. With this anthology, Scego highlights the diversity of the African diaspora in Italy. Contributors have backgrounds from Eritrea, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Rwanda, Tunisia, Haiti, and more.

While working on the anthology, Scego noticed the shared anger and exhaustion that AfroItalian women face due to systematic racism and discrimination. As such, in the introduction of Future, Scego describes the book as Italy’s contemporary J’accuse (signaling Émile Zola’s open letter to the president of the French Republic), as it “publicly denounces power and injustice.” More about the anthology can be found in a CUNYTV news segment, featuring interviews and readings by contributors Marie Moïse, Angelica Pesarini, and Camilla Hawthorne, hosted by the Calandra Italian American Institute of Queens College. The recording of Stories without Borders: A Conversation with Igiaba Scego, hosted by Casa Italiana of NYU, also focuses on Future and Scego’s other works like Beyond Babylon (trans. Aaron Robertson) and La linea del colore (The Color Line). (This response paraphrases Scego's answer to a similar question during Casa Italiana's virtual event, Stories without Borders).

What were the Fulbright projects that took you to Italy?

Barbara: I began studying Italian at Middlebury College, as a way of connecting with my cousins who were born and raised in the Veneto region. Italy was the only place my cousins had ever lived. Yet, because of their Blackness, they were always treated as outsiders. Learning the language helped me dive deeper into their experiences.

Studying in Italy my junior year sparked new questions about Blackness and sharpened my attention to how transnational contexts inflect the experience of Blackness. In Florence, I met and connected with many young people who, like my cousins, existed between Italian and Outsider – never quite considered Italian because of their Blackness. Meeting them pushed me to begin questioning what Blackness means across geographies and relationships.

So I returned to Italy in 2016 as a Fulbright Researcher to examine the complex interplay of education, citizenship, and identity for first and second-generation immigrant youth. I explored how school teachers create teaching practices that are responsive to these youths’ cultural and linguistic assets. I observed that, despite best intentions, teachers' relationships with Black students often reproduced antagonistic dynamics that led to those students, more than any other racialized group, being labeled as badly behaved or academically deficient. I joined various discussions held by Black Italians. I listened as they unpacked the reality of concurrently embodying Blackness and Italianness in a culture that perceives this duality as incompatible, an “irreconcilable paradox” as framed by Italian scholar Angelica Pesarini.

Candice: At Mount Holyoke College, I enrolled in Italian language courses to understand political commentaries about black communities during the immigration crisis. Through my majors Anthropology and Italian, I broadened my knowledge of analyzing culture and positionality with an intersectional approach to inform my research projects about the politics of Blackness, entrepreneurship, and institutions in Italy. I went to Italy for the first time as a year-long study abroad student in Bologna. My senior thesis analyzed my ethnographic research in that city and argued that Italian immigration laws negatively impact employment prospects for West African merchantmen, regardless of their legal status. Those laws also marginalize and racialize their bodies through biopolitics and biopower. I remained curious about the experiences of businesswomen of African descent and decided to apply for a Fulbright.

As a Fulbright Student Researcher in 2016-17, I researched how Italy’s racial and political history impacts the reception and promotion of businesses owned by African women and descendants in northern Italy. The women I spoke with had businesses in the hospitality, beauty, and e-commerce industries. They either moved to Italy as adults and had been living in the nation for years, or they were born and/or raised there as children and have been there their whole lives. They did not describe themselves as outsiders, even though the nation continues to view and treat them through immigration and exclusive citizenship laws shaped by the nation's colonial past. However, national organizations and political commentators see them as people who will save the country from a slow economy. This is usually juxtaposed with bodies that are considered illegitimate or a threat to the nation, often Black and Brown people of migratory backgrounds who do precarious labor to feed and sustain the needs of the population. I admire how these women challenge the boundaries of entrepreneurship and cultural production in Italy, considering the racist and neoliberal anxieties that impact their projects’ creation and perception.

Like Barbara, I also spoke with activists and changemakers about racial politics and notions of privilege. I was curious about the similarities between my experiences as an African American woman and those of Black Italians and the differences and ways that I may benefit from certain situations due to my Americanness. Tina Campt coined the concept of "intercultural address,” or how we see the commonalities and similarities between African American and Black European experiences through references to the hegemonic black American cultural capital across the globe. This notion significantly impacted my research and the articles I wrote during my Fulbright and currently shapes how I approach translation and promoting AfroItalian women’s voices.

Candice, you talked about doing a review of Future for The Dreaming Machine and mentioned that Pina, the editor, gave you the idea to translate one of its texts-- is that what made you think of doing the entire anthology?

Candice: As we spoke about writing a review in English for the book, Pina also gave me the idea to translate one of its stories. I thought it was a great idea to accompany the review.

I don’t remember the exact moment I decided to translate the anthology, but I do remember planning to do it as we got closer to the event at the Calandra Italian American Institute in February. I shared the idea with Marie Moïse, Angelica Pesarini, and Camilla Hawthorne as we prepared for the live event. It came up during the conversation on the importance of Black translators translating the works of Black authors. Barbara, who also has experience in translation and was also at the live event, shared her enthusiasm, and we decided to collaborate on it.

Barbara, what drew you to this project?

Barbara: I came to this project initially through Candice and then fully committed to it after reading the stories myself and hearing Marie Moïse, Angelica Pesarini, and Camilla Hawthorne, three contributors to the anthology speak at the Calandra Italian American Institute of the City University of New York.

In my various experiences living and studying in Italy, I was always acutely aware of my AfroItalian friends and colleagues’ liminal positionality. Because of my own identity as a Ghanaian American, and my background studying Black transnationalism, I empathize with aspects of their struggle. Nonetheless, I found that I did not always have the full scope of language to explain their specific positionality within the global Black diaspora to my non-Italian friends and colleagues. Translating Future is an opportunity to have these AfroItalian women speak for themselves on the world stage. In my role as a translator, my purpose is to create space for the anthology writers to grapple with and make meaning about their lives and have them be reachable to an English-speaking audience. These stories, which run the gamut of engaging Blackness in many forms is a relational process that I, as the translator, help bring forth.

Candice, you mentioned Tina Campt and her "concept of ‘intercultural address’ or the ways that we see the commonalities and similarities between African American and Black European experiences.” I'm wondering how that has affected your translation strategies in the anthology. And the opposite: are there examples of any differences you've struggled with in the translation?

Candice: Definitely. I think about power as an African American within the African diaspora, specifically amongst African descendants in Europe, and that discourses about race or systemic inequalities can be directly or indirectly about the United States. I try to reflect and act on how I may be contributing to perpetuating a hegemony of Americanness within the diaspora, so I think that one way to try and destabilize that is starting with myself.

As for strategies, Barbara has helped me with this as we work on the translation. One thing is using the word “folks” when perhaps a better word is “people.” I think “folk” is typical, maybe even expected, in American English vernacular, and the word “people” is clearer to all audiences.

Another example is translating racial slurs, which exist in the anthology. Misogynoir is not something that cannot be easily translated from one language to another, without considering the historical trauma those words come from. That’s something I am grappling with.

Like Barbara, I empathize with the struggles that AfroItalian women face. As I translate, I am learning a lot and hugely appreciate these women for sharing their stories. I hope that future readers will experience the same admiration that Barbara and I feel for them and their work.

How many authors are in the anthology?

Candice: Eleven authors contributed stories. The preface and postface were written by two academics, Dr. Camilla Hawthorne, from the U.S. and Prisca Augustoni, from Brazil. Igiaba Scego wrote the introduction.

We both appreciate that the anthology connects the experiences and struggles of AfroItalian women to others in the diaspora, such as Brazil. That type of trans-diasporic dialogue is essential and demonstrates that these histories and futures don't occur in a vacuum, or should only be compared to what occurs in the US.

Do you expect you'll be able to collaborate with the authors as you work on the translation?

Candice: Yes! Thankfully, Barbara and I already had connections with the contributors, either first degree or more. We plan to involve them in the process as we want to make sure that their words are reflected accurately and justly to English-speaking audiences.

Do you have any favorite texts among them?

Barbara: I can’t shake the stories by Marie Moïse or Angelica Pesarini.

Candice: I enjoyed all of them. In addition to the stories by Marie Moïse and Angelica Pesarini, "And Yet There Was Still a Smell of Rain" by Alesa Herero and "The Marathon Continues" by Addes Tesfamariam resonated with me.

#Candice Whitney#Barbara Ofosu-Somuah#Igiaba Scego#Marie Moïse#Camilla Hawthorne#Angelica Pesarini#Future. il domani narrato dalle voci di oggi#AfroItalians in translation

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Westphalian

Linguistic Diversity Challenge — Regional Edition

Post # 10 / 12: Western Eurasia (Europe, the Caucasus, Mesopotamia and the Levant, etc.)

What is the language known as to linguists, and by the speakers themselves?

endonym: Westfäölsk, Westfäälsch Platt;

exonyms: Westfälisch, Westphalian, Westphalien, Westfaals

Where is the language spoken?

Westphalia region of Northwest Germany

How many speakers does the language have?

Speaker numbers are difficult to come by. Most speakers nowadays are heritage speakers at best, they may be close to 2 million people.

True Westphalian is currently spoken mostly by elderly people. The majority of the Westphalian population speak instead a local variety of standard German with a Westphalian accent. One of the reasons for the diminishing use of Westphalian is the rigorous enforcement of German-only policies in traditionally Low German-speaking areas during the 18th century. Westphalian, and Low German in general, unlike many of the High German dialects, were too distant from standard German to be considered dialects and were therefore not tolerated and efforts were made to stamp it out.

Nevertheless, the Westphalian dialect of German includes some words that originate from the dying Westphalian language, which are otherwise unintelligible for other German speakers from outside Westphalia. Examples include Pölter [ˈpœltɐ], "pajamas", Plörre [ˈplœʁə] "dirty liquid", and Mötke [ˈmœtkə] "mud, dirt".

What are some of the languages relatives and is it part of a contact area?

Indo-European >> Germanic >> Northwest Germanic >> West Germanic >> North Sea Germanic >> Altsächsisch >> Middle-Modern Low German >> Low German >> West Low German >> Westphalic

neighbors are Dutch dialects, Eastphalian, and Middle German dialects

Is the language written? If it is, with what script?

Latin script with umlaut signs; used in official documents from 9th through 19th centuries; nowadays rarely written

What is the language like grammatically?

Westphalian is in some respects more conservative than Middle or High German dialects, e.g. in still distinguishing dative and accusative plural forms of pronouns (us, usik : uns ‘us’; ju, juwik : euch ‘you’) or the occasional reflex of diminutive suffixes not found elsewhere in (West) Germanic.

What is the language like phonologically?

Its most salient feature is its diphthongization (rising diphthongs, called “broken vowels” or “vowel breaking”). For example, speakers say ieten ([ɪɛtn̩]) instead of essen ‘to eat' or uapen ([ʊɐpn̩]) for offen ‘open’.

Its consonantism is characterized by the lack of the second Lautverschiebung (consonant shift) so that many plosives which were turned into fricatives in HIgh German remained plosives just like in their English cognates: Appel ‘apple’, to ‘to(wards)’, maken ‘to make’

youtube

What made you choose the language?

It is the language of the region where I grew up, native language of most of my childhood friends and primary school teachers; I don’t speak it myself, but I understand it fairly well.

To speakers of other German dialects, it often sounds a bit rough and grumpy, boorish and archaic. I like it though.

Resources:

https://www.ethnologue.com/language/wep

https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/west2356

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Westphalian_language

https://wals.info/languoid/lect/wals_code_gwe

http://www.language-archives.org/language/wep

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Westf%C3%A4lische_Dialekte

https://www.lwl.org/komuna/pdf/mundartregionen_westfalens.pdf

https://www.lwl.org/LWL/Kultur/komuna/isa/#/10

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Machine Translation Market Scenario, Strategies and Forecast Analysis Report till 2022

September 21, 2021: The global machine translation market is anticipated to reach USD 983.3 million by 2022. Increasing quantity of website content, growing requirement for cost competence in translation, and the huge quantity of language knowledge demanded exceeds the capability of human translation, which consecutively is expected to propel the machine translation industry. Globalization increases the demand to deal with the linguistic variety of local audiences and web content. The fabrication of content generated online, increasing the importance of business in budding markets, and the demand for allowing worldwide collaboration amongst employees is likely to drive machine translation industry growth over the forecast period.

Machine translation price are far inferior to that of conventional human translation. It is also rapid than human translation. It is commonly utilized for soaring volume content that would or else take gigantic resources for translation, and this is likely to fuel the machine translation industry. Accessibility of free of charge translation engines and shortage of translation accuracy is expected to restrain market expansion over the forecast period. Main restraints for the machine translation industry are a shortage of quality, demand for expert skills and editing, opposition from free translation service provider, and complexity in estimation & measurement of quality. One of the major shifts budding in the market is the incorporation of the translation procedures in the project plan.

Many enterprises with a worldwide presence does not have a devoted multilingual website for reaching out to every region. This might obstruct their growth as various users globally might be capable to understand only in their inhabitant languages. Another major challenge obstructing the expansion of the industry over the forecast period is the creative marketing materials present in the market, which a machine is not able to grasp and demands human understanding for delivering & translation the definite meaning. This comprises certain legal documents and creative marketing content.

Request a Free Sample Copy of this Report @ https://www.millioninsights.com/industry-reports/machine-translation-mt-market/request-sample

Consumers in the electronic market demands competent translation of document in direction to haste up time to market and publication processes. An electronics enterprise demands publishing to be completed in various languages to offer press releases, user manuals, for commercial, product launches and marketing catalogs. Machine translation service providers builds up customized engines for the customer in the electronics market that are well coincided with the industry’s particular terminologies and technological descriptions. The machine translation industry finds its functions in healthcare to enhance communication demands of physicians.

On the basis of application, the market can be segregated into automotive, medical, Electronics, healthcare, electronics, information technology, and others. On the basis of technologies, the market can be segregated into RBMT, SMT and others. The SMT (statistical machine translation) uses a model to create and analyse text in the aimed language in contrast to this RBMT (rule-based machine translation) uses linguistic rules over the sourced language, to create text in the aimed language. On the basis of the geographical region, this market can be segregated into North America, Asia Pacific, Europe and Middle east and Africa. North America is expected to capture maximum revenue over the forecast period. Machine translation is very effectual way of eradicating language barriers around various regions. The main factor responsible for the expansion of the North American machine translation industry is the growing number of government initiatives and service providers in the area.

The presence of a huge quantity of service providers has assisted them to boost market expansion in the U.S. Google, Microsoft, two of the greatest technology providers are based in the North America who have made SMT (statistical machine translation) technology admired with their online engines. Increasing Globalization and requirement to deal with different cultural groups have to lead to the increased recognition of translation technology in Asia Pacific. The increasing proliferation of smartphones and growing penetration of internet are likely to fuel machine translation market expansion in Asia Pacific over the forecast period. The demand to address various cultural groups and growing globalization is expected to fuel the expansion of the machine translation system in Asia Pacific. The main challenge of this market in Asia Pacific is the need for specialist skills, shortage of quality, complexity in measurement & estimation of quality, and increasing competition from free language conversion.

Browse Full Research Report @ https://www.millioninsights.com/industry-reports/machine-translation-mt-market

Some of the key players in the market are SYSTRAN, Lionbridge, Lighthouse IP, Lingotek, Cloudwords Inc, SDL PLC and Moravia IT. This market is less fragmented but the competition is expected to increase over the forecast period. As the need for customization and personalization of machine, translator is going to increase over the forecast period, which in return will fuel the need for innovation in this market.

Market Segment:

Machine Translation Application Outlook (Revenue, USD Million, 2012 - 2022)

• Automotive

• Military & Defense

• Electronics

• IT

• Healthcare

• Others

Machine Translation Technology Outlook (Revenue, USD Million, 2012 - 2022)

• RBMT

• SMT

• Others

Machine Translation Regional Outlook (Revenue, USD Million, 2012 - 2022)

• North America

• Europe

• Asia Pacific

• Latin America

• MEA

Get in touch

At Million Insights, we work with the aim to reach the highest levels of customer satisfaction. Our representatives strive to understand diverse client requirements and cater to the same with the most innovative and functional solutions.

Contact Person:

Ryan Manuel

Research Support Specialist, USA

Email: [email protected]

0 notes

Text

Machine Translation Market 2025 Report by Key Growth Drivers, Challenges, Leading Key Players Review

Machine Translation Market is anticipated to reach USD 983.3 million by 2022. Increasing quantity of website content, growing requirement for cost competence in translation, and the huge quantity of language knowledge demanded exceeds the capability of human translation, which consecutively is expected to propel the machine translation industry. Globalization increases the demand to deal with the linguistic variety of local audiences and web content. The fabrication of content generated online, increasing the importance of business in budding markets, and the demand for allowing worldwide collaboration amongst employees is likely to drive machine translation industry growth over the forecast period.

Request a Sample PDF Copy of This Report @ https://www.millioninsights.com/industry-reports/machine-translation-mt-market/request-sample

Market Synopsis of Machine Translation Market:

Machine translation price are far inferior to that of conventional human translation. It is also rapid than human translation. It is commonly utilized for soaring volume content that would or else take gigantic resources for translation, and this is likely to fuel the machine translation industry. Accessibility of free of charge translation engines and shortage of translation accuracy is expected to restrain market expansion over the forecast period. Main restraints for the machine translation industry are a shortage of quality, demand for expert skills and editing, opposition from free translation service provider, and complexity in estimation & measurement of quality. One of the major shifts budding in the market is the incorporation of the translation procedures in the project plan.

Many enterprises with a worldwide presence does not have a devoted multilingual website for reaching out to every region. This might obstruct their growth as various users globally might be capable to understand only in their inhabitant languages. Another major challenge obstructing the expansion of the industry over the forecast period is the creative marketing materials present in the market, which a machine is not able to grasp and demands human understanding for delivering & translation the definite meaning. This comprises certain legal documents and creative marketing content

Consumers in the electronic market demands competent translation of document in direction to haste up time to market and publication processes. An electronics enterprise demands publishing to be completed in various languages to offer press releases, user manuals, for commercial, product launches and marketing catalogs. Machine translation service providers builds up customized engines for the customer in the electronics market that are well coincided with the industry’s particular terminologies and technological descriptions. The machine translation industry finds its functions in healthcare to enhance communication demands of physicians.

On the basis of application, the market can be segregated into automotive, medical, Electronics, healthcare, electronics, information technology, and others. On the basis of technologies, the market can be segregated into RBMT, SMT and others. The SMT (statistical machine translation) uses a model to create and analyse text in the aimed language in contrast to this RBMT (rule-based machine translation) uses linguistic rules over the sourced language, to create text in the aimed language. On the basis of the geographical region, this market can be segregated into North America, Asia Pacific, Europe and Middle east and Africa. North America is expected to capture maximum revenue over the forecast period. Machine translation is very effectual way of eradicating language barriers around various regions. The main factor responsible for the expansion of the North American machine translation industry is the growing number of government initiatives and service providers in the area.

View Full Table of Contents of This Report @ https://www.millioninsights.com/industry-reports/machine-translation-mt-market

Table of Contents:-

Chapter 1 Methodology and Scope

Chapter 2 Executive Summary

Chapter 3 Machine Translation: Market Variables, Trends & Scope

Chapter 4 Machine Translation: Product Estimates & Trend Analysis

Chapter 5 Machine Translation: Application Estimates & Trend Analysis

Chapter 6 Machine Translation: End-use Estimates & Trend Analysis

Chapter 7 Machine Translation: Industrial End-use Estimates & Trend Analysis

Chapter 8 Machine Translation: Regional Estimates & Trend Analysis

Chapter 9 Competitive Landscape

Chapter 10 Machine Translation: Manufacturers Company Profiles

Get in touch

At Million Insights, we work with the aim to reach the highest levels of customer satisfaction. Our representatives strive to understand diverse client requirements and cater to the same with the most innovative and functional solutions.

0 notes

Text

Linguistic Diversity Challenge: The Region Edition

You can see the challenge here

Day 1/12 - South and Central Asia

Tajik:

1. What is the language known as to linguists, and by the speakers themselves?

It’s known as Tajik, Tajiki and Tajiki Persian in English (tadjique in Portuguese, my native language) and забо́ни тоҷикӣ́ (zaboni tojikī),meaning Tajik language by the native speakers and форси́и тоҷикӣ́ (forsii tojikī) meaning Tajiki Persian. It’s written as تاجیکی in Persian.

2. Where is the language spoken?

It’s the official language of Tajikistan and it’s also spoken in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

3. How many speakers does the language have?

The number varied quite a lot in different sources, but the number of speakers is around 8 million people.

4. What are some of the languages relatives and is it part of a contact area?

Tajik is an Indo-european language, being a part of of the Indo-Iranian branch of this family. It is considered a variety of Persian.

picture source

5. Is the language written? If it is, with what script?

The language is written and it uses a modified version of the Cyrillic alphabet (yes, the one used in Russian language) and the Persian alphabet, also called Perso-Arabic script. An adaptation of the Latin alphabet was also used for a short period of time.

6. What is the language like grammatically?

Tajik uses the subject – object – verb order, unlike English that uses the subject – verb – object order.

To make it more clear: In English we say “I watch a movie”, in a the subject – object – verb order the phrase would be “I a movie watch”.

The grammar is very similar to the Persian grammar. The nouns don’t have a grammar gender (languages like German do), but they have a grammatical number. Articles (the, a, an, in English) don’t exist and the adjectives usually come after the noun, the opposite of the English language.

7. What is the language like phonologically?

The language has 6 vowels and 24 consonants

In this the Cyrillic alphabet and the International Phonetic Alphabet were used to represent the vowels (the first picture) and the consonants (second picture).

8. What made you choose the language?

The fact that it’s a variety of Persian written with the Cyrillic alphabet is very interesting to me. I have been interested in this language for a while and this challenge seemed like a good opportunity for me to learn more about it. Also finding a good amount of information about the language online was important too.

Sources 1 and 2

#linguistic diversity challenge#linguistic diversity challenge: the region edition#tajik#tajik persian#languages#langblr

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is India's digital ID system, Aadhaar, a tech solution for a socio-economic problem?

New Post has been published on http://khalilhumam.com/is-indias-digital-id-system-aadhaar-a-tech-solution-for-a-socio-economic-problem/

Is India's digital ID system, Aadhaar, a tech solution for a socio-economic problem?

ID systems should allow for social inclusion and human rights

Biometric details being captured in an Aadhaar enrolment centre in Kolkata, West Bengal, India (Biswarup Ganguly, CC-BY-3.0)

This post was first published on Yoti as a part of Subhashish Panigrahi's Digital Identity Fellowship. It has been edited for Global Voices. The world's largest biometric ID system, Aadhaar, assigns Indians a 12-digit unique identity number which is tied to a range of citizen beneficiary services. The programme was meant to be a technological solution to both existing and emerging socio-economic challenges, designed to help ensure inclusion in India. In practice, however, it has done the opposite, deepening the exclusion of marginal and vulnerable communities. Aadhaar began to take shape in 2009, when the Indian National Congress (INC) was in government, but saw aggressive implementation under the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), currently in office, which holds a majority at the federal level and wields strong influence in many provinces. The system has therefore been used in both federal and provincial public programmes on a massive scale, but exclusion persists. It was hoped that, after a decade of Aadhaar, issues like the country's long history of racial oppression — which existed long before British colonisation and continues long after the country became a democratic republic in 1947 — would be addressed. Instead, many marginalised communities find themselves in a multitude of troubles, unable to access basic amenities and services. Conversations with members of several such communities — as part of research conducted for the MarginalizedAadhaar project (see Field Diaries #1, #2 and #3) — indicate that the most marginalised among them have been further excluded as a result of the absolute trust in ‘tech-solutionism’ displayed by several state entities. However, the technological biases that have come out of the systemic social oppression in Indian society — especially in the context of Aadhaar — are yet to be addressed.

‘Tech-weapons of mass exclusion’

When viewed through the lenses of different demographics — social, political, economic, regional, linguistic, religious, and most importantly, access to privileges for those at the bottom of the pyramid — one can only grasp a tiny portion of what a national biometric-based identity system like Aadhaar means to citizens. By their very nature, ID systems need to allow for social inclusion and the rights of individuals to address issues across the spectrum — from widespread inequality to the nuances associated with the Adivasis, especially the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups. If they do not, people with privileges but with no understanding of diversity and inclusion, end up building ‘tech-weapons of mass exclusion.’ For instance, Aadhaar has been deployed for biometric-based authentication in the distribution of food rations through the Public Distribution System (PDS), a federal government initiative that provides food and other essential commodities to those in need. The objective, of course, is to eradicate poverty, but data from the country's census showed that between 2001 and 2011, the number of people in need rose from 21 to 26.8 million, a 22.4% increase.

Contextualising tech

Technology, particularly in India, cannot be discussed without bringing up systemic racial discrimination. The country’s political power dynamics are much more racially divisive than ever before, to the point where they have now become part of the apparatus for exclusion. The caste system divides people of the Hindu faith into four major classes, of which some are considered outcasts, or ‘untouchables’. These communities are collectively known as Dalits in progressive discourses; in India's constitution, they are classified as Scheduled Castes (SC). The BJP, the ruling right-wing nationalist party dominated by “upper-caste” Hindus, has been pushing to exclude the Dalit, Muslim and Adivasi people — and several other marginalised communities — through divisive policies. From a human rights perspective, the technological implementations of these policies often translate into inherent and serious design flaws.

A Muslim woman in the state of Assam who was declared as a “Doubtful Voter” in the National Register of Citizens. (Screengrab from a video reportage by NewsClickin. CC-BY 3.0).

Access to information in native languages

Curiously, in a country where there have been no less than 402 documented internet shutdowns since the BJP came to power in 2014, the Aadhaar system relies on the internet to function. People wanting to get food rations must authenticate their identity via a fingerprint-based process, and authorities at the ration centres use an online portal to verify the information. Just as concerning is the fact that as many as 104 million Adivasis, already largely excluded because they come from low-income groups, are further sidelined because they cannot find any information about Aadhaar in their native languages. In the following video, Sora-language speaker Manjula Bhuyan from Odisha, India, highlighted the importance of accessing information about digital identity in one’s native language. Downloadable videos with captions and transcripts can be accessed here. [youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o3CmhAAKNp8?feature=oembed&w=650&h=366]

Declared illegal citizens

The impact of this systemic bias is broad. It ranges from Dalit and Muslim schoolchildren from low-income families being denied scholarships because of Aadhaar system errors, to Muslim citizens being harassed and asked to provide proof of citizenship. Muslims in the state of Assam have been among the hardest hit — 1.9 million of them out of the state's population of 33 million were declared illegal during the National Register of Citizens (NRC), a programme designed to eliminate illegal immigrants. The video below says that the state of digital identity took a critical turn when these 1.9 million people were declared illegal. Downloadable videos with captions and transcripts can be found here. [youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sKPuvZAxUPI?feature=oembed&w=650&h=366] The NRC exercise came to a momentary halt because of the COVID-19 pandemic, but new waves of terror began to unfold among those who have been declared illegal. Ashraful Hussain, an activist who works closely with many discriminated Assamese Muslims, recently noted, “Most Muslims — and even many Hindus of [West] Bengal origin — were purposely excluded in the ‘original inhabitant‘ category by the officers who were in charge of the NRC drive.”

Read More: Millions in India's north-eastern Assam state at risk of losing citizenship

The 1.9 million people whose names were left out of the list of “legal citizens” have one last option — appearing before what's known as a foreigner’s tribunal to prove their citizenship in a judicial process. Hussain fears, however, that even though these already marginalised people are becoming poorer as a result of lockdown restrictions, they will need to pay the legal costs associated with having to prove their citizenship once COVID-19 restrictions are lifted — and the exclusion goes much further. According to Hussain, “As many Muslim women are illiterate and are unable to find documents to establish their parental link, these women and their children are out of the [NRC] list.” The NRC is deeply linked with Aadhaar. As attorney Tripti Poddar explained, the collection of individuals’ biometric data happened during the NRC process. Those who made it to the NRC were issued Aadhaars; those who did not were denied. Poddar further argues that even a foreigner residing in India can receive an Aadhaar, but Indian citizens flagged by the NRC can be stripped of their constitutional rights.

Written by Subhashish Panigrahi · comments (0)

Donate · Share this: twitter facebook reddit

0 notes

Text

Building New Bridges in Education

The idea of a bridge has always served as a powerful model for education. As a concept it anchors the ideals of education in something less intangible, more achievable. According to UNESCO, the role of education is twofold: to empower individuals “to become active participants in the transformation of their societies”; to enable these individuals “to live together in a world characterized by diversity and pluralism.”[1] It is in this very real sense that education functions as a bridge. By promoting certain values and attitudes it opens dialogue and fosters relationships, allowing experiences to be shared, common concerns to be communicated and mutual recognition to be reached.

This role of education in building bridges between people and places has particular resonance in the UAE, which is celebrating 2019 as a year of tolerance. The analogy is also at the heart of a growing demand for executive education programs in the Gulf region. For professionals seeking to gain a competitive advantage in international business, a broad knowledge base and flexible skill set is essential. In traditional management education, ‘bridge building’ has become a specialized business strategy. The globalized nature of business environments means that individuals must now be able to cross “the cultural divide” through effective, contextualized communication techniques. With the rapid developments in technology, there is also an increasing need to overcome “the digital divide” through more advanced technical knowledge.

In response to these demands, universities have had to adopt a ‘bridge building’ approach to education. Today’s complex problems require multi-faceted solutions. Multi/inter-disciplinary frameworks that allow students to supplement traditional skills with new tools have become the norm. It is in line with this model, for example, that universities are integrating digital business strategies into their established curricula.

In recent years, however, the challenges facing business professionals have become increasingly complex. The existing educational framework appears outmoded and ineffective because it no longer reflects the reality facing students in the 21st century. In August 2017, the Harvard Business Review released an issue entitled “The Truth about Globalization”, which details a retreat from a global, international outlook into localized markets and mentalities.[2] To navigate this new environment, a new set of skills is required. Basic knowledge of the global business world, an ability to bridge cultural boundaries, is no longer a sufficient response to today’s changing international climate. There is now a need for a deeper understanding of the complexities and contradictions of globalization, an awareness that bridges that bring proximity can also introduce distance and separation.

The same is true of the digital divide. The growing number of mental health complaints among students (discussed in the March edition of this magazine) suggests that the digital skills gap is more complex than first believed. Research now shows that technology and social media promote feelings of isolation and anxiety. In making the world more connected these platforms also cuts individuals adrift. As a bridge, they bring people together while also keeping them apart. Filling the digital skills gap is therefore no longer a simple question of acquiring new technical knowledge. What employers require, paradoxically, are improved social skills: versatility, social intelligence, self-awareness. With privacy concerns, data security and disinformation threats now the top corporate priorities, companies need individuals to analyze, and not just consume, technological data. Digital competences must come hand in hand with an ability to adopt a critical, disengaged position.

To respond to these issues, the education sector needs to re-think how it employs the concept of a bridge in delivering knowledge. In light of the demands now placed on professionals, the traditional inter-disciplinary approach appears limited. In practice, the convergence of multiple viewpoints can lead to a narrowing of perspectives, as each discipline becomes more rooted in a particularized area of expertise. This model connects different fields but, in doing so, it also keeps them separate. How, then, can we adapt the notion of the bridge to address these challenges?

In Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi, where the motto is “a bridge between civilizations”, a new direction becomes possible. SUAD is unique in that it embodies the very ideals it represents. As a bridge between countries and cultures, it creates mobility and proximity between places and people. As a meeting point between Paris and Abu Dhabi, it connects a long-standing tradition in academic achievement with a commitment to innovation and excellence.

In SUAD, tolerance is not just an idea but an every-day reality. With a student body spanning over 80 nationalities, it is a symbol of the UAE’s commitment to diversity and inter-cultural exchange. In this very practical sense, SUAD offers a new way of defining the role of education in the 21st century. By putting principles into practice, it forces us to re-think the bridge not as something connecting separate locations, but as the point where alternative perspective are transformed into a single collective.

For these reasons, SUAD provides a hub for innovation in research and teaching practice. As a faculty member, I have spent the last two years exploring the possibilities of adapting curricula and methodology in line with a new concept of ‘bridge building’. In my research, I am developing an alternative form of disciplinary exchange that moves beyond the limitations of the traditional approach.

Rather than offer different modules in isolation (mutualisé), this new approach maximizes the potential of the classroom as a space where separate fields directly overlap (à la croisée). The idea is not just to bridge fields that remain at a distance (“inter-disciplinarity”) but to allow subjects to directly converge, in such a way that they are taught simultaneously (what I term “infra-disciplinarity”). At a practical level, traditional curricula are not simply supplemented with alternative approaches; instead, new tools and methods are acquired on the basis of pre-established knowledge.