#mahuru māori

Text

Happy Date Mentioned in OFMD Day!

I went with Mahuru rather than Hepetema as a shout-out to everyone doing Mahuru Māori i tēnei tau. Ko koutou ā runga!

"kē" can mean a lot of things but here it means something close to "actually"

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

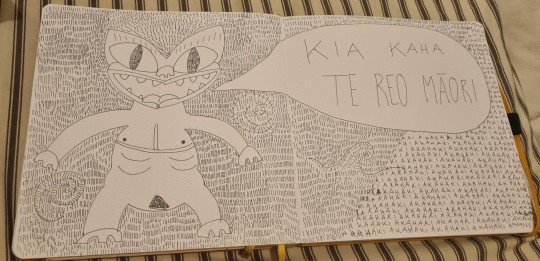

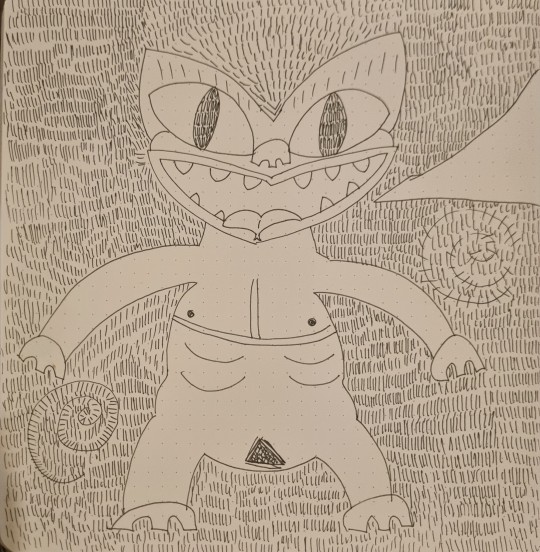

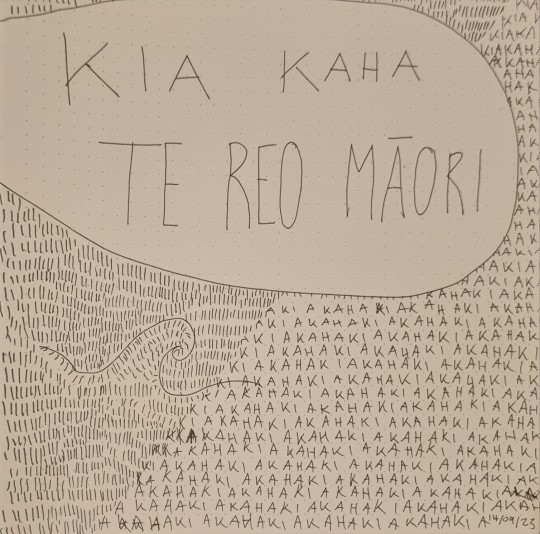

Ko tāku toi tēnei mō te wiki o te reo

Māori.

Ko uaua tāku reo. He taonga reo. E rua, e rua. Ki ōku tūpuna, kia whakarongo

au ki a koutou. Ka tarai au.

Kia kaha Te Reo Māori ❤️🖤

---

Tāku kōrero i te reo Pākehā:

This is my art for Māori Language week.

My language is hard. It is a treasure. These both are true.

To my ancestors, I will/am listening to you. I will try.

Be strong, Māori language.

#te reo Māori#Māori#te wiki o te reo māori#new zealand#taniwha#aotearoa#mahuru māori#māori tag#my art

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forgot until I saw the poem that its Mahuru Māori. Maybe I should be writing my posts in te reo Māori this month? (Māori lunar calendar month)

look up www.mahurumaori.com if you want to know what it is.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Brought my boy Miles to Te Ataarangi today - covid has split our class into two rooms, and we needed another classmate in our room. Happy Mahuru Māori! https://www.instagram.com/p/CElIdigM4U_/?igshid=15qdea57tvyrp

0 notes

Text

Community Justice, Maori-Style

As U.S. policy makers look to dismantle mass incarceration, a pair of New Zealand programs that involve the larger community in setting parameters for punishment and rehabilitation may be worth a closer look.

Earlier this month, I attended the hearing of a woman facing a vehicular homicide charge in Kaikohe, a rural town on New Zealand’s North Island. It provided an answer to a question that is increasingly being asked in our country.

Liz Glazer, director of the New York Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, recently put it better than anyone else I’ve heard so far.

“Have we reached the limits of what the traditional structures of the criminal justice system can produce in safety?” she wrote. “If yes, what other approaches should we use?”

The hearing I watched was held in what’s called a Matariki court – a hybrid Western-tribal proceeding. The Court was an initiative set up by the late Chief District Court Judge Russell Johnson, who was concerned about the rate of imprisonment of Māori offenders.

The statistics are well known to most in the community. Māori make up 17 percent of the population generally, but comprise 50 percent of the male Māori prison population and somewhere in the order of 60 percent of the female prison population. Those statistics are out of all proportion to the population numbers that Māori represent within the community in general.

Judge Greg Davis, courtesy New Zealand Justice Ministry

That should resonate with justice reformers in the U.S., where for example African Americans make up 13 percent of the general population and 33 percent of the sentenced prison population.

In the Matariki court, presided by Judge Greg Davis, participants sat facing one another at the same level around a collection of tables inside a more typical courtroom in the small-town courthouse that had been redesigned to resemble a traditional Maori meeting house.

Before the proceedings began, family members sang a welcome:

Haere mai rā

Haere mai rā

Tēnā rā koutou katoa

E ngā iwi nui tonu rā

Tēnā rā koutou katoa

(Welcome, welcome,

Welcome to you all.

To the many tribes,

Welcome to you all.)

That was followed by a traditional hongi, during which the judge, defense, prosecution, defendant, and all observers pressed noses and foreheads together to share the breath of life.

Judge Davis explained how the court was established to redress the historic “systemic bias against Maori” at the hands of the criminal justice system.

Tribal elders then welcomed all to court in te reo Maori, New Zealand’s other official language, emphasizing the proceeding’s importance.

The defendant, whom I’ll call Maili (not her real name), had been awaiting trial for more than a year, during which she continued training to be a teacher and attended counseling. During this time, her remorse over the death of her victim (her daughter) became increasingly apparent to even the police-prosecutor.

Thus, he was not seeking incarceration for Maili, nor license suspension (that would be unfeasible in her rural community, he told me afterwards).

He spoke directly and compassionately to Maili during the proceedings, referring to her as “just as much of a victim” as her child.

After the hearing, Judge Davis accompanied me for a visit to the “invisible remand” Mahuru program run by the Nga Puhi Iwi (“tribal”) Social Services Youth Team under contract with New Zealand’s Oranga Tamariki (Ministry for Children).

A youth in New Zealand’s Mahuru juvenile justice program. Photo courtesy NewZealand Ministry of Justice

Instead of remanding young people to the nearest detention facility three hours away in Auckland, a family from the Nga Puhu Iwi, or tribe, takes them into their home. During the day, two Mahuru mentors work closely with them, assuring and reinforcing their cultural connection to the Iwi.

What application could this have in the U.S.?

Organizations and researchers like JustLeadershipUSA, #CUT50 and criminologist James Austin have long urged that the U.S. cut our incarceration rate in half in the coming years. However, while federal efforts like Justice Reinvestment have sought to cut prison populations and reinvest in communities, precious few prison dollars have actually found their way to communities.

(One notable exception to this trend occurred in 2017 in Colorado, where policy makers recently captured savings from prison downsizing to fund direct services and small business loans in two communities heavily impacted by imprisonment).

With over 600,000 people returning home from prisons every year – a number that would surely grow if we were to cut the prison population in half – we ignore communities at our, and their, peril.

Researcher Robert Sampson has found that the more cohesive communities are, the safer they are, a phenomenon sociologists dub “collective efficacy.” If community members keep an eye on their neighborhoods, we need fewer cops and prisons to do so.

Research by Princeton’s Patrick Sharkey has found that one way of measuring the increase in efforts to strengthen communities in a city is to count the number of non-profit organizations established to reduce violent crime or build stronger communities.

When he and his colleagues did so, they found that, for each additional such non-profit per 100,000 city residents, the city in question experienced a one percent decline in its murder rate.

In other words, communities that are more cohesive are safer communities, even controlling for other factors.

New York City, which has experienced massive, simultaneous declines in crime and incarceration since the mid-1990s, has taken Sampson’s and Sharkey’s research to heart (even consulting with them while doing so), launching the Mayor’s Action Plan (“MAP”) in 2014.

New York’s MAP program

Through MAP, 12 city agencies from the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, including police, housing, mental health, education, probation and community development, are working together with community residents in 15 New York City Housing Authority developments to co-design neighborhood-based efforts to increase public safety.

These have ranged from hiring formerly incarcerated people to mentor neighborhood kids, expanding the summer youth employment program and extending hours in community centers until midnight.

MAP also employs crime prevention through environmental design (dubbed “CPTED”). In one housing development, this included using a special MAP opportunity fund to turn an empty lot into a vibrant barbeque area for residents.

Initial signs are promising. Violent crime declined by 8.9 percent in the 15 MAP housing developments in the effort’s first four years, compared to a 5.1 percent decline in New York City’s housing developments that are not part of MAP. All of this is monitored side-by-side by city agencies and neighborhood residents through a regular, data-driven NeighborhoodStat meeting.

Vincent Schiraldi

Every year, the U.S. spends about $80 billion locking up 2.2 million people. People in prison often come from communities disproportionately populated by African American and Latino people. Neighborhoods often ravaged by poverty, unemployment, homelessness and failing schools.

As we look to undo the effects of mass incarceration and return people to their home neighborhoods, sound investments in community cohesion to enhance safety and justice, like those in New Zealand, Colorado, and New York City, are worth considering as models.

Vincent Schiraldi is Co-Director of the Columbia University Justice Lab and Senior Research Scientist at the Columbia School of Social Work. He welcomes comments from readers.

Community Justice, Maori-Style syndicated from https://immigrationattorneyto.wordpress.com/

0 notes