#marguerite de navarre

Text

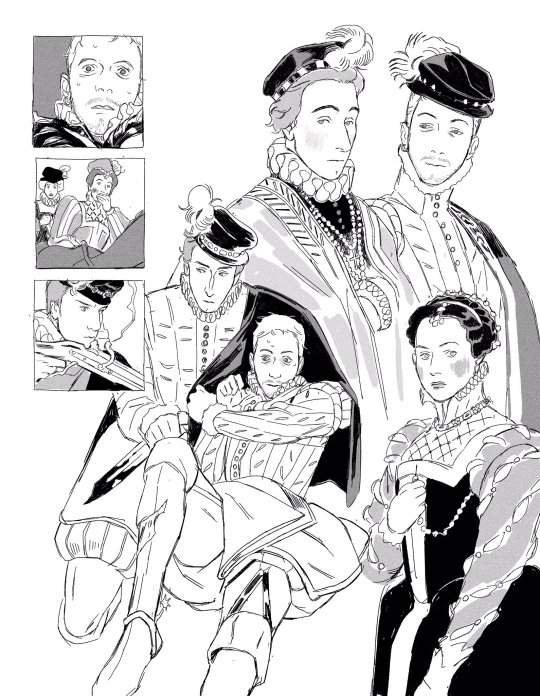

La Reine Margot - Charles IX, Henri de Navarre, and Marguerite de Valois

I.III - Un roi poète

I.XXXI - La Chasse à Courre

II.IV - La Nuit des Rois

#La Reine Margot#Alexandre Dumas#Charles IX#Henri de Navarre#Henri IV#Marguerite de Navarre#new obsession just dropped welcome to the era#Charles is callous and sickly and pathetic so naturally he's a blorbo#he can excuse religious war crimes but he draws the line at his sexy cool protestant brother in law ♥️#i havent even designed the main gays of this book...it has so much to offer#16th century

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Isabella Adjani as Marguerite de Valois in La Reine Margot (1994)

#la reine margot#la reine margot (1994)#isabella adjani#marguerite de valois#marguerite de navarre#perioddramaedit#period dramas#periodedit#*mine

790 notes

·

View notes

Text

To describe Anne Boleyn as a feminist would be an anachronism - and not nearly as appropriate an anachronism as in the case of Marguerite de Navarre and others who openly championed female equality. Marguerite did not have the word, but she was conscious of a women's "cause." There's no evidence that Anne felt similarly. But she had learned to value her body and her ideas, and she ultimately recognized that there was something unsettling about this for Henry and understood that this played a role in her downfall.

"A Perfect Storm", The Creation of Anne Boleyn, Susan Bordo

#The Creation of Anne Boleyn#Anne Boleyn#Marguerite de Navarre#Henry VIII#Tudor history#feminism#misogyny mention#sexism mention#body image mention#? just in case#text heavy#Susan Bordo

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mon, Feb 26 - Quotes from The Heptameron by Marguerite de Navarre

#the heptameron#Marguerite de Navarre#book#books#literature#french#french literature#chaotic academia#dark academia#book recommendations#bookblr#booklr#book quotes#aesthetic#girlblogging#reading#call me by your name aesthetic#call me by your name#cmbyn

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marguerite de Navarre’s discussion of courtly love, La Coche (The Coach) (1541–42), was dedicated to [Anne de Pisseleu]. The relations between Marguerite and Anne were complex. Sometimes described as rivals, they often shared tactical objectives in court politics and, though Marguerite was waspish about many others in her talks with foreign envoys, she never was about Anne. There was clearly also some sympathy between them in matters of religion, which in Anne’s case developed later into Protestantism. Marguerite’s poem is a discussion about the miseries and pains of love, which are submitted by Marguerite to the arbitration of Madame d’Étampes in the absence of her brother the king. The text also contains an extended eulogy of Anne (though not named directly) in which she is likened to ‘a sun midst stars who spares nothing for her friends, nor stoops to vengeance on her foes’. Marguerite addresses her as cousin and mistress. There are several illuminated copies, the best known in the Musée Condé showing Marguerite presenting the work to Anne."

-David Potter, "The Life and After-Life of a Royal Mistress: Anne de Pisseleu, Duchess of Étampes"

#historicwomendaily#anne de pisseleu#french history#16th century#my list#Marguerite of Angoulême#marguerite de navarre#marguerite de valois#I don't know what to tag her :(#Anne and Marguerite (+Diane de France) are the most interesting women of 16th century France to me#so I love that both of them were allies and seem to have gotten along#my post

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1510, she received ambassadors from Spain. On 16 May 1515 the English ambassador, the duke of Suffolk, requested that Henry VIII write a letter to Marguerite, since he thought her to be powerful at court. In 1519, the Venetian ambassador paid an official visit to Marguerite, by which time, he noted, she was taking the place of the queen in public ceremonies.

King's Sister — Queen of Dissent: Marguerite of Navarre (1492-1549) and her Evangelical Network, Jonathan A. Reid

#marguerite of navarre#marguerite of angouleme#marguerite de navarre#french history#mine*#quotes#history

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

is it better to speak or to die?

- Marguerite de Navarre, from The Heptameron

#i would like to know actually#yes this is also in#call me by your name#originally it’s from#the heptameron#marguerite de navarre#quotes#literature

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Is it better to speak or to die?"

the Heptameron - Marguerite de Navare (1432-1549)

#gay#dark academia#gay dark academia#love#is it better to speak or to die#call me by your name#the heptameron#Marguerite de Navarre#books and literature#literaure#bookcore#quote#tumblr quotes#quotes#aesthetic#academia aesthetic

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

“To speak or to die” but I’m still kicking so

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marguerite de Navarre, aka Margaret of Navarre, or Marguerite of Angoulême.

Portrait attributed to Jean Clouet, c. 1527.

Daughter of Charles of Orléans and Louise of Savoy, and older sister to Francis I.

Wikipedia: As an author and a patron of humanists and reformers, she was an outstanding figure of the French Renaissance. Following the example set by her mother, Marguerite became the most influential woman in France during her lifetime when her brother acceded to the crown in 1515. Her salon, known as the “New Parnassus”, became famous internationally.

Explain reference to Parnassus.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Same Florida girl, same

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

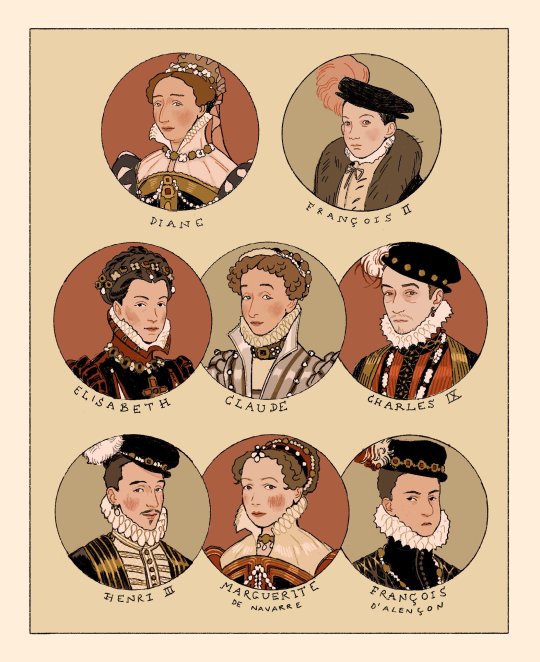

Last of their name

#house of valois#french history#charles ix#henri iii#françois d'alençon#marguerite de navarre#claude de france#elisabeth de france#diane de france#françois II#la reine margot

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Reformation & Repression under Bishop Briçonnet of Meaux - World History Encyclopedia

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/2123/reformation–repression-under-bishop-briconnet-of/

View On WordPress

#1231#Bishop Briçonnet of Meaux II#Catholic#Charles V#Concordat#Council of Sens#France#John Leclerc#Lefevre d&039;Etaples#Lodève#Marguerite de Navarre#Martin Luther#Meaux#Paris#Pope Gregory IX#Pope Julius II#Pope Leo X#Protestant Reformation#The Inquisition#Virgin Mary#William Farel

0 notes

Text

Blanche, Marguerite, and Queenship

Blanche's actions as queen dowager amount to no more than those of her grandmother and great-grandmother. A wise and experienced mother of a king was expected to advise him. She would intercede with him, and would thus be a natural focus of diplomatic activity. Popes, great Churchmen and great laymen would expect to influence the king or gain favour with him through her; thus popes like Gregory IX and Innocent IV, and great princes like Raymond VII of Toulouse, addressed themselves to Blanche. She would be expected to mediate at court. She had the royal authority to intervene in crises to maintain the governance of the realm, as Blanche did during Louis's near-fatal illness in 1244-5, and as Eleanor did in England in 1192.

In short, Blanche's activities after Louis's minority were no more and no less "co-rule" than those of other queen dowagers. No king could rule on his own. All kings- even Philip Augustus- relied heavily on those they trusted for advice, and often for executive action. William the Breton described Brother Guérin as "quasi secundus a rege"- "as if second to the king": indeed, Jacques Krynen characterised Philip and his administrators as almost co-governors. The vastness of their realms forced the Angevin kings to rely even more on the governance of others, including their mothers and their wives. Blanche's prominent role depended on the consent of her son. Louis trusted her judgement. He may also have found many of the demands of ruling uncongenial. Blanche certainly had her detractors at court, but she was probably criticsed, not for playing a role in the execution of government, but for influencing her son in one direction by those who hoped to influence him in another.

The death of a king meant that there was often more than one queen. Blanche herself did not have to deal with an active dowager queen: Ingeborg lived on the edges of court and political life; besides, she was not Louis VIII's mother. Eleanor of Aquitaine did not have to deal with a forceful young queen: Berengaria of Navarre, like Ingeborg, was retiring; Isabella of Angoulême was still a child. But the potential problem of two crowned, anointed and politically engaged queens is made manifest in the relationship between Blanche and St Louis's queen, Margaret of Provence.

At her marriage in 1234 Margaret of Provence was too young to play an active role as queen. The household accounts of 1239 still distinguish between the queen, by which they mean Blanche, and the young queen — Margaret. By 1241 Margaret had decided that she should play the role expected of a reigning queen. She was almost certainly engaging in diplomacy over the continental Angevin territories with her sister, Queen Eleanor of England. Churchmen loyal to Blanche, presumably at the older queen’s behest, put a stop to that. It was Blanche rather than Margaret who took the initiative in the crisis of 1245. Although Margaret accompanied the court on the great expedition to Saumur for the knighting of Alphonse in 1241, it was Blanche who headed the queen’s table, as if she, not Margaret, were queen consort. In the Sainte-Chapelle, Blanche of Castile’s queenship is signified by a blatant scattering of the castles of Castile: the pales of Provence are absent.

Margaret was courageous and spirited. When Louis was captured on Crusade, she kept her nerve and steadied that of the demoralised Crusaders, organised the payment of his ransom and the defence of Damietta, in spite of the fact that she had given birth to a son a few days previously. She reacted with quick-witted bravery when fire engulfed her cabin, and she accepted the dangers and discomforts of the Crusade with grace and good humour. But her attempt to work towards peace between her husband and her brother-in-law, Henry III, in 1241 lost her the trust of Louis and his close advisers — Blanche, of course, was the closest of them all - and that trust was never regained. That distrust was apparent in 1261, when Louis reorganised the household. There were draconian checks on Margaret's expenditure and almsgiving. She was not to receive gifts, nor to give orders to royal baillis or prévôts, or to undertake building works without the permission of the king. Her choice of members of her household was also subject to his agreement.

Margaret survived her husband by some thirty years, so that she herself was queen mother, to Philip III, and was still a presence ar court during the reign of her grandson Philip IV. But Louis did not make her regent on his second, and fatal, Crusade in 1270. In the early 12605 Margarer tried to persuade her young son, the future Philip III, to agree to obey her until he was thirty. When Philip told his father, Louis was horrified. In a strange echo of the events of 1241, he forced Philip to resile from his oath to his mother, and forced Margaret to agree never again to attempt such a move. Margaret had overplayed her hand. It meant that she was specifically prevented from acting with those full and legitimate powers of a crowned queen after the death of her husband that Blanche, like Eleanor of Aquitaine, had been able to deploy for the good of the realm.

Why was Margaret treated so differently from Blanche? Were attitudes to the power of women changing? Not yet. In 1294 Philip IV was prepared to name his queen, Joanna of Champagne-Navarre, as sole regent with full regal powers in the event of his son's succession as a minor. She conducted diplomatic negotiations for him. He often associated her with his kingship in his acts. And Philip IV wanted Joanna buried among the kings of France at Saint-Denis - though she herself chose burial with the Paris Franciscans. The effectiveness and evident importance to their husbands of Eleanor of Provence and Eleanor of Castile in England led David Carpenter to characterise late thirteenth-century England as a period of ‘resurgence in queenship’.

The problem for Margaret was personal, rather than institutional. Blanche had had her detractors at court. It is not clear who they were. There were always factions at courts, not least one that centred around Margaret, and anyone who had influence over a king would have detractors. They might have been clerks with misgivings about women in general, and powerful women in particular, and there may have been others who believed that the power of a queen should be curtailed, No one did curtail Blanche's — far from it. By the late chirteenth century the Capetian family were commissioning and promoting accounts of Louis IX that praise not just her firm and just rule as regent, but also her role as adviser and counsellor — her continuing influence — during his personal rule. As William of Saint-Pathus put it, because she was such a ‘sage et preude femme’, Louis always wanted ‘sa presence et son conseil’. But where Blanche was seen as the wisest and best provider of good advice that a king could have, a queen whose advice would always be for the good of the king and his realm, Margaret was seen by Louis as a queen at the centre of intrigue, whose advice would not be disinterested.

Surprisingly, such formidable policical players at the English court as Simon de Montfort and her nephew, the future Edward I, felt that it was worthwhile to do diplomatic business through Margaret. Initially, Henry III and Simon de Montfort chose Margaret, not Louis, to arbitrate between them. She was a more active diplomat than Joinville and the Lives of Louis suggest, and probably, where her aims coincided with her husband’s, quite effective.

To an extent the difference between Blanche’s and Margaret’s position and influence simply reflected political reality. Blanche was accused of sending rich gifts to her family in Spain, and advancing them within the court. But there was no danger that her cultivation of Castilian family connections could damage the interests of the Capetian realm. Margaret’s Provençal connections could. Her sister Eleanor was married to Henry III of England. Margaret and Eleanor undoubtedly attempted to bring about a rapprochement between the two kings. This was helpful once Louis himself had decided to come to an agreement with Henry in the late 1250s, but was perceived as meddlesome plotting in the 1240s. Moreover, Margaret’s sister Sanchia was married to Henry's younger brother, Richard of Cornwall, who claimed the county of Poitou, and her youngest sister, Beatrice, countess of Provence, was married to Charles of Anjou. Sanchia’s interests were in direct conflict with those of Alphonse of Poitiers; and Margaret herself felt that she had dowry claims in Provence, and alienated Charles by attempting to pursue them. Indeed, her ill-fated attempt to tie her son Philip to her included clauses that he would not ally himself with Charles of Anjou against her.

Lindy Grant- Blanche of Castile, Queen of France

#xiii#lindy grant#blanche of castile queen of france#blanche de castille#grégoire ix#innocent iv#raymond vii de toulouse#aliénor d'aquitaine#louis ix#philippe ii#guérin#louis viii#marguerite de provence#aliénor de provence#alphonse de poitiers#henry iii of england#philippe iii#jeanne i de navarre#philippe iv#simon de montfort#edward i of england#jean de joinville#sancia de provence#béatrice de provence#charles i d'anjou

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“The betrayal was all the worse for Eleanor’s apparent infatuation with her new husband, although she consented to the marriage in part because it offered a means of escape from her brother’s dour court. Although she was not physically unattractive, at least compared to the other Habsburgs, Francis found it impossible to conceal the repugnance he felt for his new wife. Matters were made worse by the fact that Eleanor, at least in the early years of their marriage, seems to have been highly sexed. Pressed by the Duke of Norfolk in 1533 for an explanation as to why the marriage remained distasteful to the king and why no children had resulted from it, the king’s sister Marguerite proved unusually forthcoming. She told him that, for the past seven months, ‘he neither lay with her nor yet meddled with her’. A further explanation came when she informed Norfolk that ‘When he doth lie with her, he cannot sleep; and when he lieth from her no man sleepeth better.’ Warming to her theme, she added: ‘The queen is very hot in bed and desireth to be too much embraced’, before concluding a damning description of her carnal interest by laughingly comparing her own marital situation, saying: ‘I would not for all the good in Paris that the king of Navarre were no better pleased to be in my bed than my brother is to be in hers.’ It was made clear to Eleanor that her worth, such as it was, was to be no more than a diplomatic conduit between her husband and brother; if she expected more, she would only be disappointed.”

Leonie Frieda, Francis I: The Maker of Modern France

#Leonor de Austria#Eleanor of Austria#Francis I of France#François I#Marguerite of Navarre#Duke of Norfolk#Carlos Rey Emperador

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite the conviction of earlier scholars, like Jourda, of Marguerite's lack of political interest, she was one of the few women ever to become a ducal peer in France. The king explicitly gave his sister the duchy of Berry as a ducal peerage, and made it clear that she was given all the traditional rights held by any male duke, and in one acte explicitly stated that Marguerite was to hold all the traditional ducal powers in Alençon, adding that this included authority over the ducal exchequer.

A close look at Marguerite's correspondence with various parlements and other government officials, as well as some of her own actes, demonstrates that Marguerite was active in the administration of her territories, and also that she was a strong proponent on behalf of the nobility within those territories, operating as a powerful patron on their behalf. I argue that rather than holding titles and territories only in an honorary way, Marguerite was given and fully exercised wide political power within her territories, and at times this led to confrontations with the king about the extent of monarchical authority over that of the upper nobility.

The Power and Patronage of Marguerite de Navarre, Barbara Stephenson

#she 💜#marguerite of angouleme#marguerite of navarre#marguerite de navarre#french history#history#quotes#mine*

5 notes

·

View notes