#memphite necropolis

Text

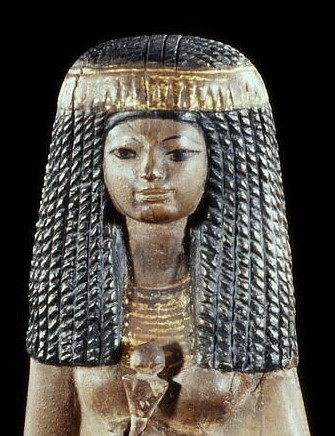

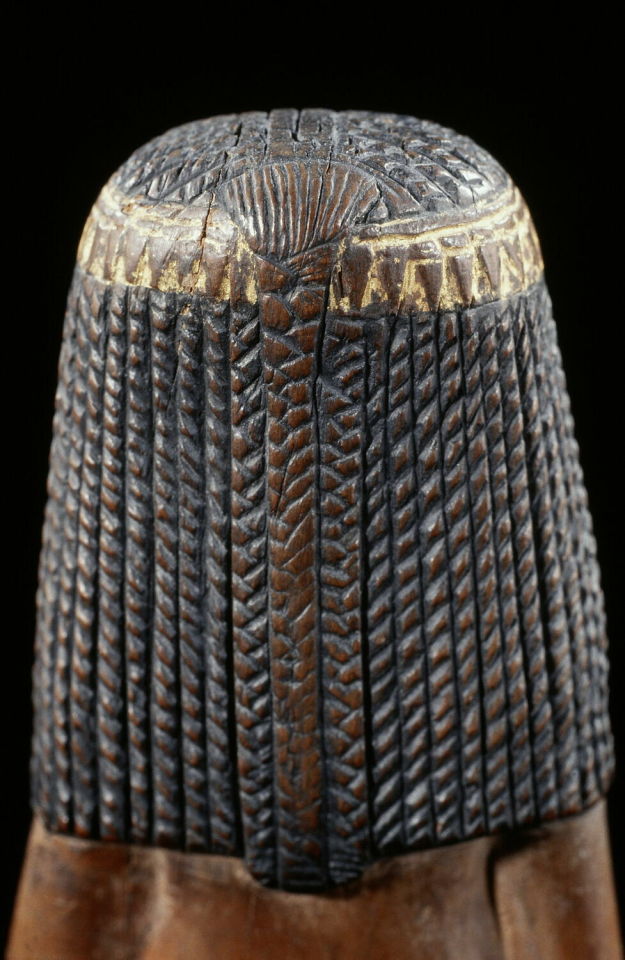

Statue - Louvre Collection

Inventory Number: N 871

New Kingdom, Pre Ramesside, Amenhotep III (-1390 - -1352)

Location Information: Saqqara (Memphite region->Memphite necropolis) (?)

Description:

woman (standing, dress, ousekh necklace, wrapping wig, bracelet, tiara)

Names and Titles: Nay (housemistress); Ptahmay (servant-sédjem-âch, brother); Ptah-Sokar-Osiris

#New Kingdom#new kingdom pr#saqqara#memphite region#memphite necropolis#dynasty 18#womens hair and wigs#NKPRWHW#louvre#N 871#statue#Nay#Ptahmay#lower egypt

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stela of the Royal Scribe Ipy

New Kingdom, late 18th Dynasty, ca. 1332-1323 BC.

From Saqqara necropolis.

Now in the State Hermitage Museum. ДВ-1072

This stela of Ipy, who held the titles “fan-bearer on the right hand [of the king]”, “royal scribe”, and “great overseer of the royal household”, carries a depiction of its owner making offering to Anubis, the embalmer deity, who is seated at the offering table. The introduction of this subject is an extremely important characteristic of the era.

In earlier times, depictions of deities in private tombs occurred only sporadically, while in the reign of Tutankhamun such scenes of worship began to occupy a central place in them. In this way, people were apologizing to the gods for the abolition of their cults under the previous ruler, Akhenaten. Stylistically the stela is also characteristic of Tutankhamun’s time, when works were produced, especially in the Memphite region, that were marked by the exceptional delicacy and softness of the relief.

Read more

369 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seker (also spelled Sokar, and in Greek, Sokaris or Socharis) is a hawk or falcon god of the Memphite necropolis in the Ancient Egyptian religion, who was known as a patron of the living, as well as a god of the dead.He is also in some accounts a solar deity as for The Temple of Seker in Memphis.

Although the meaning of his name remains uncertain, the Egyptians in the Pyramid Texts linked his name to the anguished cry of Osiris to Isis 'Sy-k-ri' ('hurry to me'), or possibly skr, meaning "cleaning the mouth".In the underworld, Seker is strongly linked with two other gods, Ptah the Creator god and chief god of Memphis, and Osiris the god of the dead. In later periods, this connection was expressed as the triple god Ptah-Seker-Osiris.

Seker was usually depicted as a mummified hawk and sometimes as a mound from which the head of a hawk appears. Here he is called 'he who is on his sand'. Sometimes he is shown on his hennu barque which was an elaborate sledge for negotiating the sandy necropolis. One of his titles was 'He of Restau' which means the place of 'openings' or tomb entrances. Like many other gods, he was often depicted with a Was-scepter.

In the New Kingdom Book of the Underworld, the Amduat, he is shown standing on the back of a serpent between two spread wings; as an expression of freedom this suggests a connection with resurrection or perhaps a satisfactory transit of the underworld.Despite this, the region of the underworld associated with Seker was seen as difficult, sandy terrain called the Imhet (also called Amhet, Ammahet, or Ammehet; meaning 'filled up').

Seker, possibly through his association with Ptah, has a connection with artisans. In the Book of the Dead, he is said to fashion silver bowls and at Tanis a silver coffin Sheshonq II has been discovered decorated with the iconography of Seker.

Seker's cult centre was in Memphis, and festivals in his honor were held there on the 26th day of the fourth month of the akhet (spring) season. While these festivals took place, devotees would hoe and till the ground, and drive cattle, which suggests that Seker could have had agricultural aspects about him.

Seker is mentioned in The Journey of Ra: the myth used to explain what happens during the night when Ra travels through the Underworld. According to the myth, Seker rules the Fifth Kingdom of Night, which is called "Hidden", and is tasked with punishing the souls of evildoers by throwing them into a boiling lake.

As part of the festivals in akhet, his followers wore strings of onions around their necks, showing the Underworld aspect of him. Onions were used in embalming people - sometimes the skin, sometimes the entire onion. When just the skin was used, it would be placed on the eyes and inside the ears to mask the smell.

Also, the god was depicted as assisting in various tasks such as digging ditches and canals. From the New Kingdom a similar festival was held in Thebes, which rivaled the great Opet Festival.

Other events during the festival including floating a statue of the god on a Henu barque, which was a boat with a high prow shaped like an oryx.

#Seker#ancient egypt#vector art#shadow theater#ancient egyptian religion#egyptian gods#gods of egypt#egyptian god#Sokar#Sokaris

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

A sketch for my second Shadow Theater blog.

Seker (also spelled Sokar, and in Greek, Sokaris or Socharis) is a hawk or falcon god of the Memphite necropolis in the Ancient Egyptian religion, who was known as a patron of the living, as well as a god of the dead.He is also in some accounts a solar deity as for The Temple of Seker in Memphis.

#Seker#ancient egypt#ancient egyptian religion#egyptian gods#gods of egypt#egyptian god#Sokar#Sokaris

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Pantheon universe, a summary

What is the Pantheon universe?

Pantheon is a series of mythological stories that take place from approximately 3000 BCE to 1200 BCE in the area known in modern times as SWANA (Southwest Asia and North Africa).

The stories assume the existence of each ancient culture’s deities while taking into account the historical conflicts between those cultures, resulting in a kind of “historical mythology” where historical conflict reflects upon the divine realm (E.G.: the Egyptian pantheon fighting the Hittite pantheon and allies in the Battle of Kadesh story).

What tags organize this blog?

Find Pantheon artwork: #iconography

Find Pantheon written work: #textcorpus

Find Pantheon lore (short posts): #lore

Find Papyrus Nabayat content: #papyrusnabayat

Find Baal Cycle content: #baalcycle

Find Battle of Kadesh content: #battleofkadesh

Individual mythology groups have their own tags below, as do some of the gods. Not all gods can be linked below for space reasons, but they are tagged.

Which gods have a prominent place in Pantheon?

Tags below the cut!

Syrian and Amorite Deities - #amorite mythology

Baal, Ugaritic god of storms #baal

Yam, Ugaritic god of the sea #yam

Mot, Ugaritic god of death #mot

Anat, Ugaritic goddess of war #anat

Astarte, Ugaritic goddess of hunting #astarte

Horon, Ugaritic god of exorcism #horon

Resheph, Ugaritic god of war, plague, and healing #resheph

Kothar, Ugaritic god of crafting #kothar

Khasis, Ugaritic goddess of crafting and war #khasis

Gupan, Ugaritic god of vineyards #gupan

Ugar, Ugaritic god of fields #ugar

Egyptian Deities - #egyptian mythology

Sutekh, god of storms, deserts, chaos, war #sutekh

Djehuty, god of knowledge, wisdom, scribes, the moon #djehuty

Hathor, goddess of love, sex, war, the sun, and music #hathor

Usire, god of the underworld and vegetation #usire

Aset, goddess of magic, wisdom, and motherhood #aset

Nebethut, goddess of darkness and mourning #nebethut

Ra, god of the afternoon sun #ra (also #khepri and #atum )

Khonsu, god of the moon, healing, and childhood #khonsu

Heru the Younger, god of kingship, the sun, and the moon #heru

Anpu, god of embalming the underworld #anpu

Ptah, god of crafting and creation #ptah

Sekhmet, goddess of war, plague, fire, healing #sekhmet

Nefertem, god of beauty and lotuses #nefertem

Sokar, god of the Memphite necropolis #sokar

Aten, god of the sun disc #aten

Hatti and Anatolian Deities - #anatolian mythology

Tarhunt, Nesian god of storms, war, and vineyards #tarhunt

Arinna, Hattic goddess of the sun #arinna

Telipinu, Hattic god of storms, fertility, and vegetation #telipinu

Nerik, Hattic god of storms and war #nerik

Ziplantil, Hattic god of storms and the underworld #ziplantil

Inara, Hattic goddess of hunting #inara

Aruna, Luwian god of the sea #aruna

Hasameli, Hattic god of crafting #hasameli

Taru, Hattic-Kaskian god of storms #taru

Zilipuri, Hattic-Kaskian god of crafting #zilipuri

Iluyanka, Hattic-Kaskian god of the Black Sea #iluyanka

Arma, Nesian god of the moon #arma

Kasku, Hattic god of the moon #kasku

Hurrian Deities - #hurrian mythology

Teššub, god of storms #tessub

Sauska, goddess of war and sex #sauska

Tasmisu, god of war #tasmisu

Aranzah, god of the Tigris River #aranzah

Kumarbi, god of grain and the underworld #kumarbi

Hebat, goddess of queenship #hebat

Kiase, god of the sea #kiase

Sarruma, god of the mountains #sarruma

Simige, god of the sun #simige

Kusuh, god of the moon #kusuh

Mukišanu, sukkal of Kumarbi #mukisanu

Impaluri, sukkal of Kiase, #impaluri

Umbu, Alalakhian god of the moon #umbu

Hedammu, god of the sea #hedammu

Sumerian and Babylonian Deities - #babylonian mythology

Enlil, god of storms and wind #enlil

Enki, god of the subterranean waters, crafting, wisdom #enki

Iškur, god of storms #iskur

Marduk, tutelary god of Babylon #marduk

Nabu, god of scribes, knowledge, and wisdom #nabu

Nisaba, goddess of scribes and grain #nisaba

Ninurta, god of war and storms #ninurta

Sharur, divine mace of Ninurta #sharur

Inanna, goddess of war and sexuality #inanna

Nergal, god of war #nergal

Nanna, god of the moon #nanna

Utu, god of the sun #utu

Ereškigal, goddess of the underworld #ereskigal

Assyrian Deities - #assyrian mythology

Aššur, tutelary god of the city Aššur #assur

Adad, Akkadian god of storms and war #adad

Erra, Akkadian god of war, pestilence, fire, and disorder #erra

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apis Bull, 663-525 B.C.E

Bronze

Egyptian

------------------------------------------

One of the most important animal deities of ancient Egypt was the sacred Apis bull, whose worship is attested from Dynasty I. Near the Ptah temple at Memphis, Egypt's old capital, a living representative of the Apis bull was stabled. He was paraded out at festive occasions to participate in ceremonies of fertility and regeneration. The bull that played this important role was selected for displaying color patterns, such as a white triangle on the forehead and black patches resembling winged birds on the body. When Apis bulls died, they were embalmed and buried with all honors. Beginning with the reign of Amenhotep III in Dynasty 18, the place of Apis burials was a huge and growing underground system of chambers called the Serapeum in the Memphite necropolis, Saqqara.

-Description from The Met

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Italian- British Egyptologist Luigi Prada on divination in ancient Egypt (with a reference to Herodotus as source on this subject)

“Dreams, rising stars, and falling geckos: divination in ancient Egypt

Moving on from a neglected discovery by the EES, Luigi Prada leads us into the little-known world of ancient Egyptian divination and its practitioners. In addition to popular techniques such as dream interpretation and astrology, we discover that the ancient Egyptians enquired after their future also through the behaviour of animals, the occurrence of thunder, and several other natural phenomena.

Between 1964 and 1976, the excavations of the Egypt Exploration Society at the Sacred Animal Necropolis in North Saqqara produced such an overwhelming wealth of finds that scholars are still busy researching and publishing them today, half a century later (see Heinz and Vander Wilt in EA 49). But even when promptly published, some of the results of this fieldwork have remained virtually unknown outside specialist circles. This is the case with the archive of Hor of Sebennytos, an Egyptian priest who lived in the second century BC ...Like several of his fellow priests, one of Hor’s leading interests and activities was oneiromancy – that is, dream interpretation.

Dreams were always an object of fascination for the ancient Egyptians (and many other ancient societies as well). In the liminal dimension of slumber, it was believed that direct communication with the divine and the netherworld would be possible. A particularly famous example of such a divine encounter is narrated in the so-called Dream Stela of Thutmosis IV (c. 1400 BC), which still stands between the front paws of the Great Sphinx at Giza... This Eighteenth Dynasty-inscription tells how the young prince Thutmosis, having fallen asleep by the monument, sighted in a dream the god Harmakhis-Khepri-Re-Atum, with whom the Sphinx was identified at the time. The god asked the prince to clear his statue of the sands that had covered it and restore it to its ancient splendour, in exchange for which he would grant him the throne of Egypt. Clearly a piece of post-eventum political propaganda, this stela nevertheless exemplifies the special regard in which dreams were held.

Dream Stela of Thutmosis IV. In a specular scene above the hieroglyphic text, the king gives offerings to the Sphinx, identified with the god Harmakhis.

It is particularly in the Graeco-Roman Period, however, that we witness an exponential rise in the textual and material evidence related to dreams. Accounts of dreams were increasingly recorded on papyri or ostraca, as in the case of Hor of Sebennytos’ archive. Dreams still featured in formal texts as well, such as the exquisite funerary stela of Taimhotep in the British Museum... The wife of Pasherenptah, High Priest of Ptah in Memphis during the reign of the famous Cleopatra VII, Taimhotep recounts in her autobiography how, after having three daughters, she and her husband prayed to Imhotep, the son of Ptah, that a male heir be granted to them. The god listened to their prayers, appearing in a ‘revelation’, asking for works to be carried out in his temple in returnfor his intercession.

Ostracon Hor 3 verso. Line 22 includes the first mention of Rome in an Egyptian text, with regard to the Roman ultimatum that put an end to the Syrian invasion of Egypt in 168 BC

Focus: Hor of Sebennytos Hor of Sebennytos was a priest active in the Memphite necropolis in the first half of th e2nd century BC. His archive, published in 1976 and consisting of approximately 70 ostraca – i.e. inscribed potsherds – written mostly in Demotic, gives an account of his daily occupations and preoccupations. The topics dealt with in these texts, which are mainly personal notes and drafts of documents, include the cult of the ibises and their mummies, oracles and dreams. Some of them also have historical relevance, as they relate important political events seen from a humble priest’s perspective. Such is the case of text no. 3, where Hor records a prophetic dream that he had at the time of the Sixth Syrian War (170–168 BC), when Egypt was occupied by the enemy forces of Antiochus IV, King of Syria, and the Ptolemaic dynasty seemed to be on the verge of collapse. In this dream, Hor saw that, despite all odds, Egypt and the Ptolemies would be saved – as, in fact, they were in the summer of 168 BC, when Antiochus peacefully withdrew from Egypt after receiving an ultimatum from Egypt’s (then) mighty ally: the Roman Republic.

But the importance of dreams was not limited to those featuring divine epiphanies. Dreams of a trivial or even haphazard content could also be considered potential vehicles of hidden messages about a person’s future. An entire science was developed for interpreting such dreams and unravelling their hidden messages. To call dream interpretation a science may sound at odds with modern Western concepts of superstition, but applying our modern views to the study of ancient Egyptian oneiromancy would be grossly inappropriate. Very much like medical or legal texts, dream (and, generally, divination) books belonged to scribal and temple libraries, being a prerogative of the learned. Dream interpretation handbooks, also known as oneirocritica, are the best- and longest-attested type of divinatory literature from Egypt. The earliest known such manuscript is P. (= papyrus) Chester Beatty 3... Now in the British Museum, it comes from the village of Deir el-Medina and dates to the time of Ramesses II (13th century BC). It originally belonged to the scribe Qenherkhepshef, whose preoccupations with sleep are further attested from other items once in his possession... Each line of this manuscript contains a description of a dream with its defining features and its interpretation, setting out what would befall the dreamer or his relations.Thus, in its col. 2/21, we read: ‘If a man sees himself in a dream eating donkey-meat: good, it indicates his promotion’. Almost one and a half millennia later, in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, dream books still thrived, and are attested in larger numbers than ever. Handbooks of the kind that Hor himself may have used are now divided into a myriad of chapters, each dedicated to a different topic: dreams about sex, about drinking, about animals... – basically any topic one could think (and thus dream) of. Within each chapter, individual dreams are still listed line by line, followed by their interpretation.Thus, within the section discussing sex-related dreams in P. Carlsberg 13, a manuscript from 2nd century AD- Tebtunis, a town in the Fayum,one may find: ‘If (a woman dreams that) a snake has sex with her: (it indicates that) she will find herself a husband. (But) if she is (already) married, she will become ill’ (frag. b, col.2/27–28)

Stela of Taimhotep, BM EA 147. Line 8 gives the reason for Taimhotep’s distress and her praying for Imhotep’s intervention

Below: Papyrus Chester Beatty 3, BM EA 10683. Colums 8-11 recto: note the elaborate layout of this dream book

Bottom: funerary headrest of Qenherkhepshef, BM EA 63783. The object’s funerary use, associating slumber with death, clearly transpires from the hieroglyphic inscription, which mentions “a good sleep in the West (=the netherworld) and is surrounded by apotropaic figures.

But how did this science operate? How are the dreams and their respective interpretations matched? A rationale is indeed present, though at times not easily detectable. In the dream quoted above, the explanation is based on a (wholly Freudian!) association, assimilating the snake with a phallus and, therefore, with the image of a male partner. As for the dream from P. Chester Beatty 3, the coupling is instead based not on analogy of image or content, but of sound – namely, on wordplay as the words for ‘donkey’ (Egyptian ΄a΄a) and ‘promotion’ (Egyptian s΄a΄a) sounded alike

That divination was a particularly serious matter in Graeco-Roman times is also suggested by the concrete business that stood behind it. Not only Egyptian priests like Hor were active as dream interpreters: in the same area of Memphis, Greek-language soothsayers, too, were at work, interpreting dreams and advertising their skills to the increasing number of Greek residents in Egypt. One, who probably lived shortly before Hor, left behind what we may call his own ‘shop-sign’, where, in Greek, he boasts that ‘I interpret dreams, having (this talent) as an order from the god. With good luck! This interpreter comes from Crete’...

Business sign of a Cretan dream interpreter, CGC 27567. The decoration mixes Egyptian and classical styles. Underneath the Greek text is an image of the Apis bull, worshipped in the Serapeum at Saqqara, just a short distance from where this item was discovered.

But divination was far from limited to oneiromancy. In the fifth century BC, the Greek historian Herodotus included divination amongst the inventions of the Egyptians, saying that they had discovered ‘more omens than all other peoples’ (II.82). He was not exaggerating: many other mantic arts were practiced by the Egyptians since at least the New Kingdom, with their number and popularity steadily increasing in Graeco-Roman times. For instance, from Ramesside Deir el-Medina and now preserved in Turin’s Museo Egizio, we have fragments of a manuscript that illustrates the practice of lecanomancy (GCT54065). This is a way of foretelling the future that uses a dish or bowl filled with water. As described in the papyrus, oil was poured on the water, and the resulting patterns and shapes formed by the floating blobs were the signs to be interpreted. Remarkably, both lecanomancy and dream interpretation were already associated with Egypt by other ancient civilisations, and are for instance featured in the Biblical story of Joseph and his brothers.

Another Nineteenth Dynasty hieratic papyrus, also from Deir el-Medina and now in Turin (CGT 54024), deals with meteorological omens, including thunder – a divinatory technique known as brontoscopy.The same art was still practiced a millennium later, in Ptolemaic times: an unprovenanced Demotic papyrus in the Cairo Egyptian Museum (inv. RT 4/2/31/1-SR 3427) lists and interprets very similar omens, also in connection with the occurrence of a ‘voice-of-Seth’ (as thunder was called in Egyptian). One passage mentions perhaps the oddest scenario: thunder accompanied by shower sof… frogs (col. 1/11: ‘if a voice-of-Seth occurs and it [literally, the sky] rains frogs…’) – not entirely impossible in the wake of tornadoes and similar violent weather events!

Amongst the various branches of divination and equal only to oneiromancy, pride of place was certainly given to astrology – a relative late comer in the world of Egyptian divination, following increased contacts with the Near East in the 1st millennium BC, particularly after the Assyrian and Persian invasions of Egypt. From the Graeco-Roman Period, a wealth of Demotic material, still largely unpublished, includes various types of documents related to astrology. First come astrological handbooks, which fall into two categories: manuals of universal astrology, interpreting the relative position of the celestial bodies in order to foretell the fate of entire countries and peoples; and handbooks of individual astrology, foretelling a person’s future based on the position of the celestial bodies at their time of birth, with respect to various divisions of the sky (including our twelve zodiacal signs, as well as other partitions known a sastrological ‘houses’). Thus, in one of the manuals of the latter type, the Demotic P. Berlin P. 8345 (from the Fayum, 1st or 2nd century AD), we can read, with regard to a man who was born ‘when Venus was in the descendant: he will quarrel much with a woman; a nasty reputation will come to him…’ (col. 2/5–7). Through such handbooks, the ancient Egyptian priests could cast life horoscopes for their customers. Working papers of these astrologers, i.e. jottings on ostraca and scraps of papyrus containing horoscopes, also survive in good numbers.

Yet another type of text, planetary tables,were essential to cast any horoscope – a kind of text that, from our modern perspective,we would classify as astronomical, rather than astrological. Such tables were painstakingly accurate numerical records of the exact dates when the celestial bodies entered specific zodiacal signs, and could extend over very long periods, years and years into the past, so as to allow an astrologer to look up the position of the planets at the time of their customer’s birth, no matter how far in the past this was, and thus cast their horoscope. A fine example are the so-called Stobart Tablets...,probably from Thebes and dating to the mid-or late second century AD. Now in the World Museum, Liverpool, they are thin wooden tablets covered with a layer of gesso and inscribed with Demotic, containing exhaustive information about planetary movements spanning the reigns of the emperors Vespasian (69–79 AD) to Hadrian (117–138 AD).

One of the Stobart Tablets, M 11467d recto. Red headings indicate years (here, regnal years14–17 of Hadrian, i.e.129/130–132/133 AD).Following each heading are five cells, one per planet, separated by horizontal lines, listingt he date (month and day) on which the planet in question entered the different zodiacal signs during that year. In the first two columns (fromt he right, as Demotic reads right to left),after ‘regnal year 14’(col. 1, line 16), we find sections for Saturn (lines 17–19), Jupiter (lines 20–22), Mars (lines 23–33), Venus (col. 2, lines 1–16), and Mercury (lines 17–30)

This brief introduction to ancient Egyptian divination cannot be considered complete before at least one further branch of divination is mentioned: that dealing with so-called animal omens, for which Demotic handbooks are attested specifically from the Roman Period. In this case, the omen to decipher was the behaviour of various animals – in most cases, their interaction or physical contact with a human observer, who was the target of the omen. The animals in question could be highly disparate, ranging from cows to dogs, from scorpions to shrewmice. Most typically, however, small animals seem to have been the favourite subject of this genre, for the simple reason that daily contact with creatures such as shrewmiceand the like, found in all Egyptian houses, wouldhave been the norm for everybody.

Just like astrology manuals, animal omen handbooks can also be roughly classified into two groups: those divided into chapters, each discussing omens pertaining to a different creature, and those entirely dedicated to one single animal. To the latter group belongs the fascinating Book of the Gecko thus titled in the original papyrus preserving it, P. Berlin P.15680, possibly from the 1st-century-AD Fayum. Geckos were as common in ancient Egypt as they are in the region today, where they can often be observed crawling on walls and ceilings.These lizards are such extraordinary climbers that their accidental fall must surely have caught the ancient Egyptians’ attention – to the point of being considered an omen. This is why all lines of the Book of the Gecko with the phrase ‘if it (i.e. a gecko) falls’, followed by the specifics of its mishap. These can include a woman’s body parts onto which the gecko would land, systematically listed from head to toe. Thus we read:

If it falls on her right breast: her heart will be greatly distressed, she should entrust herself to the god. If it falls on her left breast: she will be pleased within her family, many sons will be born to her. If it falls in between her breasts: she will fare very well, something from Pharaoh will quickly reach her (col. 2/2-4))

The handbook further proceeds by describing more elaborate situations in which a gecko may unwittingly partake, such as: ‘If it falls on a woman who is having sex: she will rejoice, she will rejoice anew over this same year’ (col. 3/21).

Many more divinatory arts are attested fromancient Egypt – far more than could be presented in this short article. What this brief introduction will have hopefully achieved is not only to introduce the reader to the world of ancient Egyptian divination, but also to give a better awareness of how much we are still discovering and learning, to this day, about the ways of ancient Egyptian life. Be it by excavations like those conducted by the EES in Saqqara, leading to the unearthing of the archive of Hor, or the product of “museum archaeology”, bringing about the publication of papyri previously lying neglected in museum collections, these discoveries are unlikely to cease any time soon, further deepening our understanding of ancient Egypt’s past through the way its inhabitants tried to read their own future.”

Source: https://www.academia.edu/33299952/Dreams_Rising_Stars_and_Falling_Geckos_Divination_in_Ancient_Egypt

Dr Luigi Prada is Assistant Professor in the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History at Uppsala University. His current project focuses on schooling and education in Ancient Egypt, with particular focus on the Ptolemaic and Roman periods. His other research interests include ancient divination (specifically, dream interpretation), bilingualism, and demotic language and literature. He participates in fieldwork in both Sudan and Egypt, where he is Assistant Director of the Oxford University Epigraphic Expedition to Elkab. . Check out his work here.

Source: https://papyrus-stories.com/luigi-prada/

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Memphite Necropolis (Pyramids of Giza). Histoire de l'Art Égyptien (1878) - Émile Prisse d'Avennes

#Wonder Rooms#Cabinet of Curiosities#Public Domain#19th Century#Émile Prisse d'Avennes#Scientific Illustration#Topography#Cartography#Geography#Archaeology#Egyptology#Egypt#Pyramids of Giza#Histoire de l'Art Égyptien#Memphite Necropolis

142 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Statue of a Seated Baboon (4th century B.C.) | Late Period–Ptolemaic Period The Sacred Animal Necropolis at North Saqqara comprised catacombs and temples 𓉞𓏏𓉐 “ḥw.t” for several sacred species, among them the baboons 𓇋𓂝𓈖𓃷 “ı͗ˁn” who during their lifetimes 𓊢𓂝𓂻𓏪 “ˁḥˁ.w” were kept in the precinct of the Temple of ‘Ptah-under-his-moringa-tree’ 𓊪𓏏𓎛𓀭𓎼𓂋𓅡𓏘𓆭𓆑 “ptḥ-gr-b3ḳ.f” at Memphis. This statue 𓂙𓏏𓏭𓀾 “ḫnty” along with another of similar size but somewhat different appearance was found by the Egypt - Beloved Land 𓇾𓌸𓂋𓆵𓇋𓊖𓊖 “t3-mrı͗” Exploration Society during its excavations at the Sacred Animal Necropolis. The statues had been anciently thrown down a stairway in the baboon catacombs, so that their original positions are not known. Geography: From Egypt, Memphite Region, North Saqqara, Sacred Animal Necropolis, Baboon catacombs, EES excavations 1968–69 Medium: Limestone, paint Dimensions: H. 70.5 cm (27 3/4 in.); W. 29.5 cm (11 5/8 in.); D. 33 cm (13 in.) 𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬𓋹𓎬 (📸 1-6) @egyptologylessons 𓋹𓊽𓋴𓆖𓎛𓇳𓎛 © ( 📸 7-9 @metmuseum and description) 𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁𓊁 #Ancienthistory #historyfacts #historylovers #ancientegypt #hieroglyphics #ägypten #egyptologist #egyptianhistory #egyptology #hieroglyphs #egypte #egyptians #egitto #埃及 #مصر #egipto #이집트 #art #culture #history #baboon #statue #metropolitanmuseumofart # https://www.instagram.com/p/Ca91m3vuagC/?utm_medium=tumblr

#ancienthistory#historyfacts#historylovers#ancientegypt#hieroglyphics#ägypten#egyptologist#egyptianhistory#egyptology#hieroglyphs#egypte#egyptians#egitto#埃及#مصر#egipto#이집트#art#culture#history#baboon#statue#metropolitanmuseumofart

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Recumbent Anubis.

Period: Late Period–Ptolemaic Period

Date: 664–30 B.C.

Place of origin: Egypt, Memphite Region, North Saqqara, Sacred Animal Necropolis, Temple deposit, EES excavations 1966–67

Medium: Limestone, originally painted black.

#ancient#ancient art#ancient sculpture#ancient egypt#ancient statue#ancient history#archeology#museum#history#Egypt#Egyptian#ancient Egyptian#egyptology#recumbent anubis#anubis#ptolemaic period#late Period#664 b.c.#30 b.c.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Another significant development concomitant with the appearance of the letters to the dead is the fact that linen was first used for writing. In a funerary context linen was commonly used for wrapping mummies and it was sometimes decorated, as the most ancient specimen of textile production from Gebelein shows. Yet writing was also associated with this particular material at the end of the Old Kingdom, as texts written on linen had funerary significance, like the late 6th dynasty letter to the dead in Cairo, the inscribed bandages and copies of the Book of the Dead, or the demotic plea from Saqqara. The fact that both bowls and linen began to be inscribed at the end of the 3rd millennium is an innovative extension of the use of writing to wider, private contexts, in all probability as a means to enhance private rituals thanks to the use of a prestigious means of expression. Under these assumptions it seems reasonable to suppose that, in the realm of the provincial elite domestic religion, it began to be widely accepted to incorporate writing and, perhaps, some elements of the former official ideology of the state which went together with it and which had been usually reserved to the dignitaries of the state. Actually, the more extensive employ of writing implies that the restricted values of the palatial culture were reaching new sectors of the Egyptian society and were being adapted to private uses, precisely at a period when the monarchy could no longer control the production and distribution of the prestigious items so typical of the palatial sphere. Such a wider diffusion and adaptation of palatial values, beliefs and ideology probably explain why inscribed statues and objects are sometimes found even in pits dug by commoners in royal cemeteries at the end of the Old Kingdom, or why some kings of the Old Kingdom became local saints venerated in the Memphite necropolis during the Middle Kingdom, apparently in a non-official context, as an expression of some kind of popular devotion, or why popular imitations of elite rituals like the “soul houses” were widely used from the end of the Old Kingdom on. Certainly the first appearance of the Coffin Texts in private burials might be understood in the same vein, as another private adaptation of an element formerly belonging to the royal sphere and to high culture. Even nonelite Egyptians had definitely access to goods and symbols previously employed by the upper social strata, if only as modest imitations such as amulets. To sum up, the interaction of the private and the state values led, on the one hand, to express family principles by means of objects firstly intended for a high culture context and, on the other hand, to incorporate into the private funerary sphere aspects and values belonging to the palatial ideology.”

-Oracles, Ancestor Cults and Letters to the Dead: The Involvement of the Dead in the Public and Private Family Affairs in Pharaonic Egypt by Juan Carlos Moreno García

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Couple Statue - Louvre Collection

Photo Focus: Meresankh

Main number: E 15592

Other inventory number: E 22769

Old Kingdom, 5th dynasty (attribution according to style) (-2500 - -2365)

Location Information: Giza (Memphite Necropolis->Memphite Region->Lower Egypt) (?)

Description:

Depicts Raherka (dignitary, inspector of scribes); Meresankh (wife). Woman (standing, dress, half-long wig, holding by the shoulder); man (standing, loincloth with rounded edge, arms dangling, short curly wig, ousekh necklace).

#Louvre#Meresankh#E 15592#E 22769#Old Kingdom#Dynasty 5#couple statue#womens clothing#okwc#giza#memphite region#memphite necropolis#lower egypt

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Women aspired to be assimilated with Hathor in the afterlife in the same manner that men desired to ‘become’ Osiris, but the goddess’ relationship to the deceased applied to men and women alike. From quite early times, especially in the Memphite region, she was worshipped as a tree goddess, 'mistress of the sycamore’, who supplied food and drink to the deceased; and from at least the 18th dynasty she served as the patron deity of the Theban necropolis, where she protected and nurtured royalty and commoners alike, either in the form of a cow or as the anthropomorphic 'mistress of the west’ who was often depicted welcoming the deceased to the afterlife with purifying and refreshing water. She was considered to receive the dying sun each evening and so it was a desire of the deceased to be 'in the following of Hathor’.”

— The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt by Richard H. Wilkinson

81 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Scholars conventionally refer to an Egyptian phenomenon that might be compared to the Mesopotamian technique of translating Gods as syncretism. It involves the collocation of two or three different Gods, leading to hyphenated names such as Amun-Re, Amun-Re-Horakhty, Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, Hathor-Tefnut, Min-Horus, Atum-Khepri, Sobek-Re, and so on. As a rule, the first name refers to the cultic/local dimension, the actual temple owner and lord of the town, whereas the second name refers to a translocal, preferably cosmic deity. Thus, Amun is the Lord of Thebes, in whom the Sun-God, Re, becomes manifest. Ptah is the Lord of Memphis, Sokar the God of its necropolis, Osiris is the God of the Underworld and the Dead whose Memphite representation is to be seen in Ptah-Sokar. This relationship between deities does not mean equation or fusion; the Gods retain Their individuality. Re does not merge into Amun or vice versa. The Gods enter into a relationship of mutual determination and complementation: Re becomes the cosmic aspect of Amun, Amun the cultic and local aspect of Re; Atum refers to the nocturnal, and Khepri to the diurnal aspect of the Sun-God. Hyphenation implies neither identification nor subordination; Amun has no precedence over Re, nor Re over Amun. In the course of time, however, this practice of "hyphenating" Gods fosters the idea of a kind of deep structure identity.

“Monotheism and Polytheism” by Jan Assmann in Ancient Religions edited by Sarah Iles Johnston (p 25)

#amun/amaunet#ra/raet-tawy#ra horakhty#ptah#seker#osiris#hathor#tefnut#min#horus#khepri#sobek#monotheism and polytheism#jan assmann

196 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The term Rosetjau ('The Entrance of subterranean passages') denoted any hole or shaft in the ground (principally tomb shafts but also natural features) which was believed to be an entrance to the netherworld.

The Memphite necropolis was the domain of the god Sokar who was called "Lord of Rosetjau", and it is likely that the depositing of shabtis close to the entrance to the subterranean realm was done in order to bring the deceased into direct proximity to the god as he entered the netherworld.

Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt, John H. Taylor

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tour To Giza, Saqqara, Dahshur & Sound Light

Tour To Giza, Saqqara, Dahshur & Sound Light

These days, do you feel a little cooped up inside? On a day trip to the Cairo Pyramids, are you tempted by the concept of the Land of the Pharaohs? That sentiment is one that we can all identify with. We are only allowed to fantasise about going beneath the Great Sphinx, strolling through Karnak's pylons, and sailing down the sinuous Nile since the novel coronavirus has put all travellers on lockdown.

Step Pyramid, Saqqara is the greatest archaeological site in Egypt and spans a 7 km stretch of the Western Desert. It was an active burial place for more than 3500 years. The necropolis is the final resting place for deceased pharaohs and their families, administrators, generals, and sacred animals. It is located high above the Nile Valley's agricultural sector. Most likely, Sokar, the Memphite god of the dead, is where the name Saqqara comes from.

Pyramids Tours in Cairo

Tour to explore the Ancient Egyptian pyramids in Giza, Saqqara and Dahshur can be started from Cairo airport ( need minimum 8 hours to visit the the area of pyramids ) , or can be started from any hotel in Cairo, and We also offer tours to pyramids from Sharm, Tours to pyramids from Hurghada, and from all Egypt cities, for more details click the link Egypt Tours, or Egypt Pyramids Tour

Usually tours start by meeting you or in your hotel or at Cairo airport ( If You are already in Egypt but in other city, not in Cairo, We will send you itinerary including travelling to Cairo , then meeting you at the airport )

Private professional tour guide will accompany you to go to visit Egyptian pyramids around Cairo, first area to visit will be Giza pyramids, Cheops, Chephren and Menkaure, tour to visit the great Sphinx, the valley temple, proceed tour to papyrus galery, then to Saqqara complex to visit the step pyramid belonging to the third dynasty to king Zoser, the mastaba of Mereruca or similar mastaba, then tour to Dahshur pyramids including the bent pyramid , and the red pyramid which is the first real pyramid constructed in all the world, Lunch meal will be included during the tour, free time for shopping in the famous bazars in Abo El Hol area ( The Sphinx area ), then at night attend Sound and light show in front of the great Sphinx, after the tour you will be transferred to your hotel or to Cairo airport.

Pyramids Tour Excludes

Pyramids Tour excludes:

- Any options such as going inside the pyramids in Giza area or to the Solar boat museum

- Beverages

- Tipping not obligatory but recommended

Pyramids Tour Includes

Pyramids Tour includes

- Meeting and assistance service at airports or hotels in Cairo

- Private professional Egyptologist English speaking tour guide

-Entrance fees to the mentioned areas as per itinerary

- Sound and light show at night

-Lunch meal

-Tour taxes

For more info

Website

Mobile and what’s App:

002 01090023837

0 notes